Abstract

We report 13 consecutive cases of complex intracranial aneurysms treated by the waffle-cone technique and the midterm angiographic results and discuss the effectiveness and safety of this technique. We performed a retrospective review to evaluating the angiographic results and clinical effectiveness of 15 cases in which waffle-cone stenting for treating broad-necked complex intracranial aneurysms at our institution up to July 2008. Among these 15 patients, we enrolled 13 patients who had undergone at least one follow-up angiography. We collected patient data including age, sex, ruptured state, aneurysm size, neck size, complications, initial Hunt and Hess (HH) grade, modified Rankin Score (mRS) at the last angiographic follow-up, and initial and follow- up angiographic results.

The mean size of the aneurysm was 10.6 mm (range, 4.0 to 20.4 mm) and the mean size of the aneurysm neck was 5.7 mm (range, 2.7 to 9.2 mm). The mean angiographic follow-up time was 13.6 months (range, six to 30 months). There were no procedure-related complications. However, there were two delayed complications. One complication was delayed focal embolic infarct and the other complication was delayed rebleeding. Angiographic improvement was achieved in two cases (15.4%), stable occlusion was achieved in seven cases (53.8%), and recanalization or compaction that needed retreatment occurred in four cases (30.8%). We think that the waffle-cone technique is an effective alternative in selected aneurysms unable to be “Y” stented or surgically clipped.

Keywords: Waffle-cone technique, complex intracranial aneurysm, endovascular treatment

Introduction

Stent placement with the proximal stent end in the parent vessel and the distal end in the sac of the aneurysm is called the “waffle-cone technique,” and it has been used by many physicians. It might be a safe and effective alternative tool for stent-assisted coiling of complex, broad-necked bifurcation aneurysms whose anatomic features are ill suited for conventional stent-assisted coiling.1,2 In recent years, new modified waffle-cone techniques have been reported.3–5 Also, a new device that is designed for improving the waffle-cone technique has been introduced.6 However, there are several concerns about the waffle-cone technique. The first concern is the potential risk of procedure-induced aneurysm perforation, especially in cases of small aneurysms. The second concern is flow diversion into the aneurysm, resulting in a higher chance of aneurysm recurrence, especially when the occlusion is not complete. The third concern is that the efferent arteries may be jailed by the stent. This could make it difficult to convert into conventional stent-assisted coiling the next time.1,3

We report 13 consecutive cases treated by the waffle-cone technique and the midterm angiographic results, and discuss the effectiveness and safety of this technique with a review of the literature.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective review to evaluate the angiographic and clinical results of 15 cases in which waffle-cone stenting was performed for treating broad-necked complex intracranial aneurysms at our institution up to July 2008. Among these patients, we enrolled 13 patients who underwent at least one follow-up angiography. Two excluded patients had not experienced any procedural complication.

To choose an adequate treatment plan, the neurosurgeon and neuro-interventionalist at our institution discussed the radiological and clinical characteristics of each patient. We suggested a surgical or endovascular option to the patients and their relatives, who gave informed consent for each treatment. Intravenous sedation using propofol and alfentanil was applied in all endovascular cases. At the beginning of the procedure, a bolus of 5000 IU of heparin was administered after insertion of a 6 French introducer sheath followed by 1000 IU/hour of heparin. In unruptured cases, pre-treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy (100 mg aspirin and 75 mg clopidogrel) was performed for five to seven days. In ruptured cases, instead of using dual antiplatelet therapy, intravenous aspirin lysine® 500 to 900 mg was injected immediately after the first coil deployment following stenting. The activated clotting time was maintained between 250 and 300 seconds as in usual cases. The stent was deployed such that the distal markers were placed more distally from the arising portion of the perforator-incorporated neck and sac. Coil embolization was mainly performed with the introduction of the microcatheter through the distal opening. Only the Neuroform3 stent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was used. The details of the waffle-cone technique performed using Neuroform3 at our institute are as follows: The Neuroform3 stent delivery system is composed of a stent-containing microcatheter and a pusher catheter that can push the stent out of the microcatheter for deployment. We used the 205 cm long conventional microguidewire (Transcend, Boston Scientific, Fremont, CA, USA) for each catheter separately. After the stent-containing microcatheter was navigated and placed into the aneurysm sac by using the 205 cm long conventional microguidewire, the microguidewire was removed. Then the pusher, which was inserted over the microguidewire again, was used for stent deployment. At the time of stent deployment in the aneurysm sac, it was better not to place the distal tip of the microguidewire in the distal end of the stent-containing microcatheter. Bare platinum coils such as the Guglielmi detachable coil (Boston Scientific, Fremont, CA, USA) and MicroPlex coil (MicroVention, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA) were used. Dual antiplatelet therapy (75 mg clopidogrel daily and 100 mg aspirin daily for six months, then aspirin alone) was started immediately after the procedure was completed.

We collected patient data including age, sex, ruptured state, aneurysm size, neck size, complication, initial Hunt and Hess (HH) grade, modified Rankin score (mRS) at the last angiographic follow-up, and initial and follow-up angiographic results. Angiographic results were categorized into three different grades.7 Class 1 was defined as complete embolization without a residual neck. Class 2 was defined as contrast filling of the residual neck. Class 3 was defined as residual aneurysm filling. The complete embolization group included Class 1 and the incomplete embolization group included Classes 2 and 3. The first angiographic follow-up was performed three to six months postoperatively according to the clinical outcome and immediate angiographic result. The next follow-up angiography was performed at six- to 12-month intervals. Based on the degree of compaction and comparison with the risk and benefit of retreatment, we selected the patients who needed retreatment.

Results

The demographic data are summarized in Table 1. There were 13 patients, of whom five were men and eight were women. The mean patient age was 59.8 years and the patients’ ages ranged from 30 to 79 years. There were nine ruptured aneurysms and four unruptured aneurysms in our study. The locations of the aneurysms were as follows: Six aneurysms were located at the bifurcation of the middle cerebral artery (MCA), four aneurysms were located in the posterior communicating artery (PcomA), two aneurysms were located in the anterior communicating artery (AcomA), and one aneurysm was located at the bifurcation of the internal carotid artery (ICA), respectively. The mean size of the aneurysm was 10.6 mm (range, 4.0 to 20.4 mm) and the mean size of aneurysm neck was 5.7 mm (range, 2.7 to 9.2 mm). The mean angiographic follow-up time was 13.6 months (range, 6 to 30 months). There were no procedure-related complications including stent migration and malposition. However, there were two delayed complications. One complication was delayed focal embolic infarct. Although this patient (Case 5) complained of motor weakness of the left extremities, the symptom recovered on its own. The other complication was delayed rebleeding. The patient (Case 9) did not visit our hospital again after the first discharge and follow-up angiography was not performed. She experienced subarachnoid hemorrhage again and the retreatment for recanalization was performed. She was transferred to another hospital and her last mRS score was 5. Angiographic improvement was achieved in two cases (15.4%), stable occlusion was achieved in seven cases (53.8%), and recanalization or compaction that needed retreatment occurred in four cases (30.8%).

Table 1.

Clinical and angiographic data of all patients.

| No. | Age | Sex | Ruptured | HH | mRS | Location | Size (mm) | Neck (mm) | Complication | Post-op | Last follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 | F | No | 0 | 0 | Rt. ICA bif | 4.0 | 2.7 | None | Class III | Class III (12) |

| 2 | 52 | F | Yes | 3 | 0 | Rt. PcomA | 9.1 | 5.4 | None | Class II | Recanalization (18) |

| 3 | 56 | F | Yes | 3 | 0 | Lt. PcomA | 16.9 | 5.6 | None | Class II | Class II (18) |

| 4 a | 55 | F | No | 0 | 3 | Lt. MCA bif | 6.9 | 5.1 | None | Class II | Class I (12) |

| 5 | 52 | M | Yes | 4 | 2 | Rt. MCA bif | 12.8 | 7.8 | Thromboembolism | Class III | Recanalization (19) |

| 6 | 72 | F | Yes | 2 | 0 | Rt. MCA bif | 20.4 | 6.8 | None | Class II | Class II (6) |

| 7 | 71 | F | Yes | 2 | 0 | Rt. PcomA | 7.3 | 4.4 | None | Class III | Class III (18) |

| 8 | 30 | M | Yes | 3 | 0 | Rt. AcomA | 7.2 | 3.9 | None | Class I | Class I (12) |

| 9 | 79 | F | Yes | 3 | 1→5 | Rt. PcomA | 20.1 | 7.8 | Delayed rebleeding | Class III | Recanalization (13) |

| 10 | 59 | M | Yes | 2 | 0 | Lt. MCA bif | 9.2 | 4.8 | None | Class II | Class II (30) |

| 11 | 67 | M | No | 0 | 0 | Rt. MCA bif | 6.2 | 4.5 | None | Class II | Class II (7) MRA |

| 12 | 74 | M | No | 0 | 0 | Lt. AcomA | 7.3 | 9.2 | None | Class III | Class II (6) |

| 13 | 35 | F | Yes | 3 | 0 | Rt. MCA bif | Fusiform | None | Class III | Recanalization (6) |

Unruptured middle cerebral artery bifurcation aneurysm in cases of another ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm.

HH: Hunt and Hess grade; F: female; M: male; mRS: modified Rankin score; AcomA: anterior communicating artery, PcomA: posterior communicating artery, MCA: middle cerebral artery, ICA: internal carotid artery, bif: bifurcation; Rt.: right; Lt.: left.

Case illustration

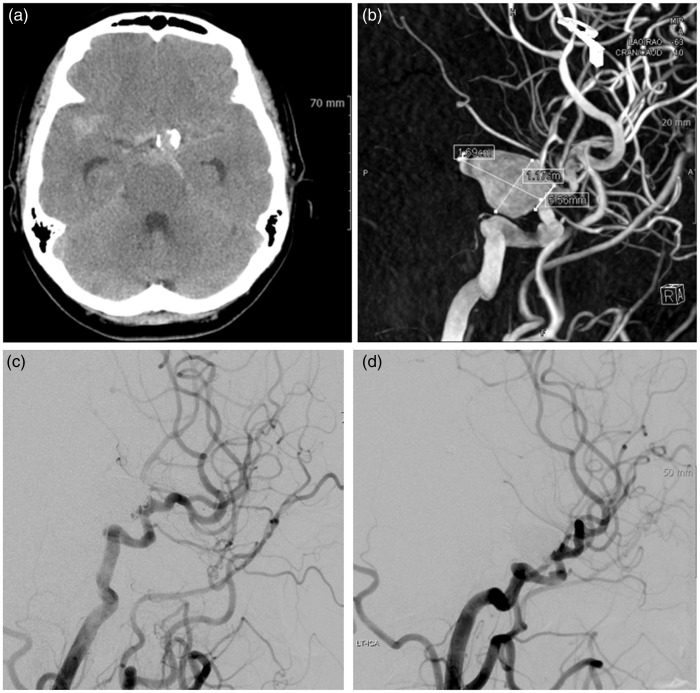

Case 3

A 56-year-old woman presented with decreased mentality (HH grade 3). Brain computed tomography (CT) scan revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the basal cistern and calcified vessels (Figure 1(a)). Three-dimensional rotational angiography (3DRA) showed a 16.9 × 11.7 mm sized left PcomA aneurysm with a 5.6 mm sized neck (Figure 1(b)). After reviewing the surgical and endovascular options, her relatives selected endovascular treatment. We planned standard stent-assisted coil embolization. Although we made an effort to navigate the stent delivery catheter into the distal ICA beyond the aneurysmal neck, it was very difficult to do so and could have resulted in aneurysm perforation or arterial dissection. Therefore, we decided to undertake waffle-cone stenting. A Neuroform3 stent (4.5 mm × 20 mm) was placed across the aneurysm orifice distal to the ICA. Coil embolization was successfully completed without any complications and patent flow in the distal ICA was clearly identified on digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (Figure 1(c)). There was improvement in the patient’s clinical course. She was discharged without any clinical or neurological symptoms (mRS 0). At 18 months after treatment, follow-up cerebral angiography showed a completely filled aneurysm and stable coil mesh (Figure 1(d)).

Figure 1.

Case 3: 56-year-old woman.

(a) Brain computed tomography scan revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage in the basal cistern and calcified vessels.

(b) Three-dimensional rotational angiography showed a 16.9 × 11.7 mm sized left posterior communicating artery aneurysm with a 5.6 mm sized neck.

(c) Coil embolization was successfully completed without any complications and patent flow in the distal internal carotid artery was clearly identified on digital subtraction angiography.

(d) At 18 months after treatment, follow-up cerebral angiography showed a completely filled aneurysm and stable coil mesh.

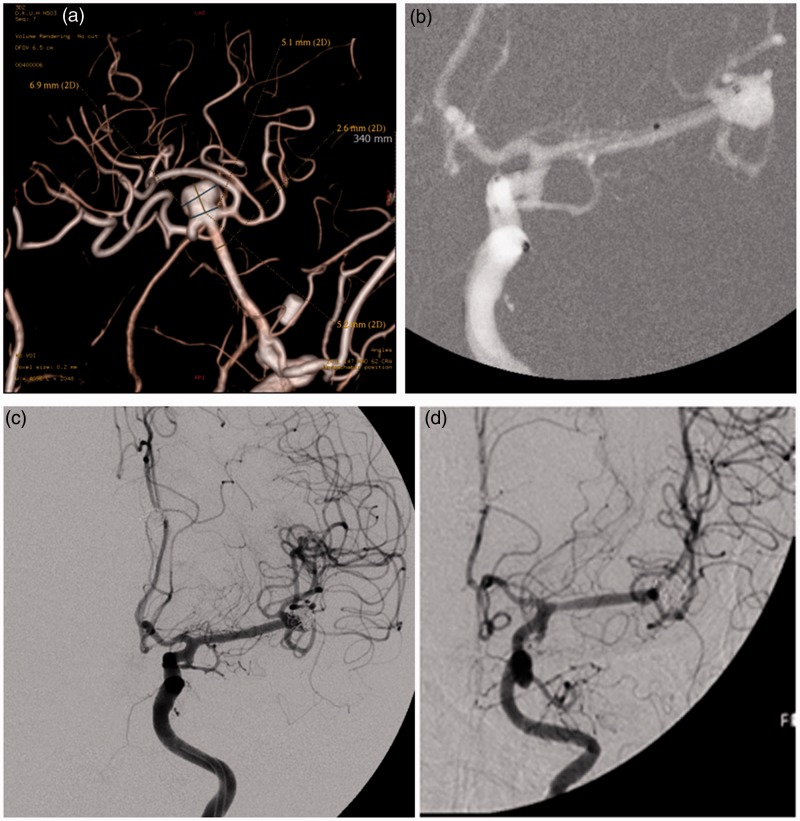

Case 4

A 55-year-old woman experienced SAH due to rupture of AcomA and she had an unruptured left MCA bifurcation aneurysm. Her clinical state was HH grade 3 initially and her clinical outcome was mRS 3 at discharge. Six months later, we tried to treat the unruptured aneurysm. The 3DRA showed a 6.9 mm × 5.1 mm sized broad-necked aneurysm at the left MCA bifurcation (Figure 2(a)). Because of the acute angled M2, we decided to perform the waffle-cone technique. After the distal tip of the stent-containing microcatheter was placed into the aneurysm sac, a 3.5 mm × 20 mm sized Neuroform3 stent was deployed from the MCA (M1) to the aneurysm sac (Figure 2(b)). Coil embolization began with the microcatheter being introduced through the distal end of the stent into the aneurysm sac. Immediate postoperative DSA revealed an incompletely packed neck of the aneurysm (Figure 2(c)). Her perioperative neurological state was unchanged and the subsequent clinical course was uneventful. Follow-up DSA at 12 months postoperatively revealed complete occlusion of the aneurysm following progressive thrombosis in the neck portion (Figure 2(d)).

Figure 2.

Case 4: 55-year-old woman.

(a) Three-dimensional rotational angiography showed a 6.9 mm × 5.1 mm sized broad-necked aneurysm at the left bifurcation of the middle cerebral artery.

(b) After the distal tip of the stent-containing microcatheter was placed into the aneurysm sac, a 3.5 mm × 20 mm sized Neuroform3 stent was deployed from the middle cerebral artery (M1) to the aneurysm sac.

(c) Immediate postoperative digital subtraction angiography revealed an incompletely packed neck of the aneurysm.

(d) Follow-up digital subtraction angiography at 12 months postoperatively revealed complete occlusion of the aneurysm following progressive thrombosis in the neck portion.

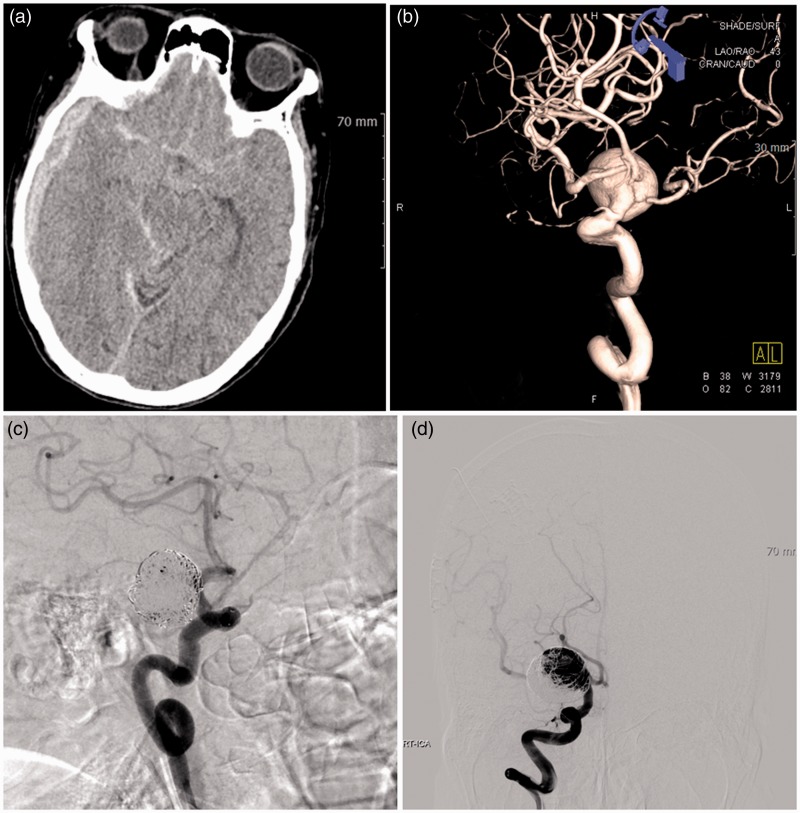

Case 9

A 79-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with stuporous mentality (HH grade 3). Brain CT scan showed SAH in the basal cistern and subdural hematoma on the right side (Figure 3(a)). A 20.4 mm × 18.9 mm sized aneurysm incorporating the branches of the distal ICA, MCA, and ACA was identified on the 3DRA (Figure 3(b)). We decided to perform the waffle-cone technique because of the indistinct aneurysm neck, parent artery wall, and orifice of the distal vessels. A 4.5 mm × 30 mm Neuroform3 stent was deployed from the distal ICA to the aneurysm sac. The aneurysm was packed incompletely without occlusion of distal arteries and branches (Figure 3(c)). She was discharged with a favorable clinical outcome (mRS 1), but was lost to follow-up. After 13 months, she experienced rebleeding due to recanalization of coiled aneurysm (Figure 3(d)). Although additional coil embolization was performed successfully, her neurological outcome was poor (mRS 5).

Figure 3.

Case 9: 79-year-old woman.

(a) Brain computed tomography scan showed subarachnoid hemorrhage in the basal cistern and subdural hematoma on the right side.

(b) A 20.4 mm × 18.9 mm sized aneurysm incorporating the branches of the distal internal carotid artery, middle cerebral artery and anterior cerebral artery was identified on three-dimensional rotational angiography.

(c) A 4.5 mm × 30 mm Neuroform3 stent was deployed from the distal internal carotid artery to the aneurysm sac. The aneurysm was packed incompletely without occlusion of distal arteries and branches.

(d) After 13 months, she experienced rebleeding due to recanalization of coiled aneurysm.

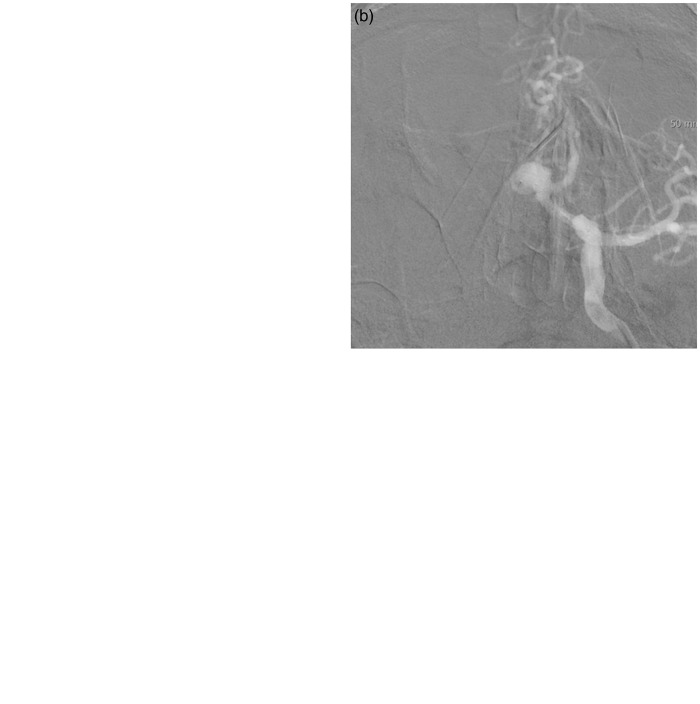

Case 12

A 74-year-old man was admitted with an incidental intracranial aneurysm. The left ICA angiogram showed a 7.3 mm × 6.4 mm broad-necked aneurysm with an acute angled contralateral ACA (A2) incorporated into the sac (Figure 4(a)). We first tried the double microcatheter technique for the aneurysm, but a coil frame could not be made. Despite several attempts, the coil loops protruded into the contralateral A2. After obtaining informed consent for stenting, we tried to perform stent-assisted coil embolization. Although we made an effort to navigate the stent delivery catheter into the contralateral A2, it was very difficult to do so and could have resulted in aneurysm perforation or arterial dissection because of the acutely curved angle between the left A1 and the contralateral A2. Therefore, we decided to undertake waffle-cone stenting. A Neuroform3 stent (3.5 mm × 20 mm) was placed across the aneurysm orifice distal to the left A1 (Figure 4(b)). Coil embolization was performed incompletely (Class 3) without any complications and the patent flow in the contralateral A2 was clearly identified on DSA (Figure 4(c)). The patient’s clinical course was uneventful. He was discharged without any clinical or neurological symptoms. Six months after treatment, follow-up cerebral angiography showed further thrombosis in the coiled aneurysm and an improved radiologic result (Class 2) (Figure 4(d)).

Figure 4.

Case 12: 74-year-old man.

(a) A left internal carotid artery angiogram showed a 7.3 mm × 6.4 mm broad-necked aneurysm with an acute angled contralateral anterior cerebral artery (A2) incorporated into the sac.

(b) A Neuroform3 stent (3.5 mm × 20 mm) was placed across the aneurysm orifice distal to the left A1.

(c) Coil embolization was performed incompletely without any complications and patent flow in the contralateral A2 was clearly identified on digital subtraction angiography.

(d) Six months after treatment, follow-up cerebral angiography showed further thrombosis in the coiled aneurysm and an improved radiologic result.

Discussion

The waffle-cone technique has several advantages compared to the Y-configured stent technique.8–11 First, the waffle-cone technique might be less complicated than the Y-configured stent technique, especially in case of an aneurysm incorporating a very small distal vessel. Second, this technique reduces the amount of metal deposited in the vessels, thus decreasing the amount of material available for possible thrombus generation. Reduced exposure of blood to a metal surface might reduce the burden of thromboembolic events and the probability of in-stent stenosis. Third, in large aneurysms on vessels with sharp curves, the stent can be easily placed into the fundus of the aneurysm and deployed, avoiding the risks of trying to maneuver wires and stents beyond the aneurysm neck. However, Hauck et al.12 suggested that the waffle-cone technique probably supports the dangerous hemodynamics that cause growth of these aneurysms and has a high chance of coil compaction at follow-up due to jet flow into the coiled aneurysm. They consider that the concept of using the waffle-cone technique is counterintuitive and probably has a high chance of recurrence and failure, as illustrated by their case. However, their case was of a giant aneurysm measuring nearly 40 mm in size. Giant aneurysm has a high chance of recanalization even when the best treatment strategies have been performed. We considered that the hemodynamic effect of the waffle-cone technique might be minimal, and incomplete coiling could be the most potent risk factor for recanalization.

The literature about the follow-up angiographic outcome of the waffle-cone technique for complex aneurysms has been summarized in Table 2. Twenty-five patients have been reported in six publications.1,8–10,12,13 We included data such as age, sex, location, size, clinical outcome, and angiographic results in Table 2. We excluded the cases that were not compatible with the proper purpose of the waffle-cone technique. For example, some cases of fusiform dissecting the aneurysm in the vertebral artery were excluded from this summary because the aneurysm was treated by the trapping technique, which is not the standard waffle-cone technique for bifurcation aneurysm and its hemodynamic characteristics were different. Nine of 25 aneurysms (36.0%) were re-treated because of recanalization or compaction. All of these aneurysms were treated incompletely (Class II or Class III) and six out of these nine recurred aneurysms were located at the basilar tip and seven aneurysms had a large size above 10 mm. We performed this technique for treating one basilar tip aneurysm, but the patient was lost to follow-up. Therefore, the data could not be included in our study. Most of the patients underwent stenting with a closed-cell stent such the Enterprise stent (Cordis Neurovascular, Miami, FL, USA) or the Solitaire AB stent (ev3 Inc, Irvine, CA, USA). Especially, most of these authors emphasized the importance of immediate post-embolization results and recommended that immediate compact embolization be performed.1,9

Table 2.

The cases of published literature.

| No | Literature | Age | Sex | Ruptured | HH | mRS | Location | Size (mm) | Stents | Complication | Post-op | Last follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hauck et al.12 | ND | ND | Yes | 2 | 0 | Ant. ophthalmic | 40 | Neuroform | None | Class III | Recanalization (48) |

| 2 | Yang et al.10 | 65 | M | No | 0 | 0 | Basilar tip | ND | Neuroform | None | Class II | Class II (6) |

| 3 | Yang et al. | 53 | M | No | 0 | 0 | AcomA | 7 | Neuroform | None | Class I | Class I (6) |

| 4 | Padalino et al.8 | 73 | F | No | 0 | 0 | Basilar tip | 10 | Enterprise | delayed stroke | Class II | Recanalization (1) |

| 5 | Padalino et al. | 32 | F | Yes | 3 | 4 | Basilar tip | 5 | Enterprise | None | Class II | Class 1 (3) |

| 6 | Padalino et al. | 63 | M | Yes | 3 | 4 | Basilar tip | 12 | Enterprise | None | Class II | Class 1 (3) |

| 7 | Padalino et al. | 67 | M | Yes | 2 | 3 | MCA bif | 17 | Enterprise | None | Class I | Class 1 (ND) |

| 8 | Liu et al.1 | 55 | M | Yes | 3 | 1 | AcomA | 12 | Neuroform | None | Class I | Class I (6) |

| 9 | Liu et al. | 73 | F | No | 0 | 0 | AcomA | 6 | Neuroform | None | Class I | Stable (8) MRA |

| 10 | Liu et al. | 62 | F | Yes | 2 | 1 | MCA bif | 11 | Neuroform | TIA | Class I | Class II (5) |

| 11 | Liu et al. | 50 | M | No | 0 | 0 | AcomA | 12 | Neuroform | None | Class II | Class II (6) |

| 12 | Liu et al. | 65 | F | Recurred | 0 | NC | MCA bif | 5 | Neuroform | None | Class I | Class I (6) |

| 13 | Liu et al. | 48 | F | No | 0 | 0 | Basilar tip | 6 | Enterprise | None | Class II | Class III(6) |

| 14 | Liu et al. | 68 | M | No | 0 | 0 | AcomA | 9 | Neuroform | None | Class II | Stable (6) MRA |

| 15 | Liu et al. | 75 | M | No | 0 | 0 | AcomA | 6 | Neuroform | None | Class I | Stable (8) MRA |

| 16 | Liu et al. | 66 | M | No | 0 | 0 | MCA bif | 9 | Neuroform | Minor stroke | Class I | Stable (3) MRA |

| 17 | Xu et al.13 | 57 | M | Yes | 1 | 3 | AcomA | 7 | Neuroform | None | Class I | Class I (12) |

| 18 | Xu et al. | 62 | F | No | 0 | 1 | Basilar tip | 9 | Neuroform | None | Class II | Class III (4) |

| 19 | Xu et al. | 47 | M | No | 0 | 0 | Basilar tip | 10 | Neuroform | None | Class I | Class I (12) |

| 20 | Xu et al. | 62 | F | No | 0 | 0 | Basilar tip | 8 | Neuroform | None | Class I | Class I (9) |

| 21 | Xu et al. | 57 | F | No | 0 | 1 | Basilar tip | 27 | Neuroform | None | Class III | Class III (4) |

| 22 | Sychra et al.9 | 47 | F | No | 0 | 1 | PCA | 14 | Solitaire | None | Class II | Recanalization (2) |

| 23 | Sychra et al. | 46 | F | Yes | 1 | 0 | MCA trif | 18 | Solitaire | None | Class II | Recanalization (6) |

| 24 | Sychra et al. | 71 | M | No | 0 | 0 | Basilar tip | 12 | Solitaire | None | Class II | Recanalization (7) |

| 25 | Sychra et al. | 43 | F | Recurred | 0 | NC | Basilar tip | ND | Solitaire | None | Class II | Recanalization (7) |

HH: Hunt and Hess grade; F: female; M: male; mRS: modified Rankin score; ND: no description, NC: no change, AcomA: anterior communicating artery, PcomA: posterior communicating artery, MCA: middle cerebral artery, PCA: posterior cerebral artery; bif: bifurcation, trif: trifurcation.

In our study, recanalization or compaction that needed retreatment occurred in four cases (30.8%). Although this percentage might be relatively higher than that obtained with another standard stenting technique, we think that this result may be acceptable because the waffle-cone technique was performed for treating a very complex aneurysm that could not be treated by the standard technique. Most of the cases of recanalization had a larger aneurysm measuring above 10 mm (75%), the aneurysm was in a ruptured state (100%), and it was coiled incompletely (100%). We propose that the risk factors for recanalization in case of the waffle-cone technique might be incomplete embolization, ruptured state of the aneurysm, and a large-sized aneurysm measuring above 10 mm. One patient (Case 9) experienced delayed rebleeding. She had a large-sized (above 20 mm) aneurysm and it was treated incompletely. However, she did not visit our hospital again after discharge and follow-up angiography was not performed. We suggest that early follow-up within six months is necessary for prevention of rebleeding due to recanalization of incompletely coiled aneurysm.

Some authors recommend the following technical tips for successful waffle-cone stenting. First, a properly placed 3D framing coil to prevent compromise of the parent vessels is required.9,14 Second, this technique is not recommended for aneurysms with narrow necks where deployment error could result in rupture, or aneurysms with necks less than 4.5 mm (size of the distal stent flare) where the opening distal end of the stent could perforate the aneurysm.8 Other authors also suggested that the technique should be used only for aneurysms larger than 4 mm, because in large aneurysms, the stent can be easily placed into the aneurysm fundus and deployed, avoiding the risks of periprocedural rupture.9 Third, some authors suggested that the most ideal location for distal markers of the Neuroform3 stent lies between the aneurysm neck and center of the aneurysm.11 Especially, according to the structure of the Neuroform3 stent, one crown segment is approximately 2 mm and the safety range of deployment out of the afferent artery and into the aneurysm by using such a method is approximately 4 mm (2 mm distance to maintain the opening of bilateral efferent arteries, and 2 mm for placement of the first crown segment of the stent into the aneurysm).11 We agree with these technical tips and the indications of the waffle-cone technique mentioned in other literatures. Additionally, we recommended that the guiding catheter should be placed as distally as possible for stable working of the microcatheter, especially in case of a distally located aneurysm. It is possible for the stent to cause rupture of the aneurysm if it jumps during navigation and deployment.10

Various intracranial stents had several advantages and drawbacks. The Neuroform3 stent, which has an open-cell design, was first used for the waffle-cone technique.2 The Neuroform3 stent has several advantages during the waffle-cone technique in contrast to other closed-cell design stents. The waffle-cone technique with the use of the Neuroform3 stent is used to form a dense stent-coil complex at the inflow zone of the aneurysm, and this complex not only decreases in-flow blood impaction but also prevents coil migration or compaction by holding the coils in the coil-stent complex.11,15 The dense stent-coil complex could be formed only with the Neuroform3 stent, which has a straight and semi-separate distal crown segment. Because in most of the closed-cell design stents such as the Enterprise stent and the Solitaire AB stent, the continuous distal end could be flared, it was difficult to form a dense stent-coil complex. The Neuroform3 stent delivery system does not have a distal tip of the wire, which is present in most closed-cell design stent systems and might result in perforation of the aneurysm wall. However, the potential problems associated with this technique are the possible inability or difficulty in retrieving a partially deployed coil and difficulty in repositioning or retrieving a partially deployed coil if the loops of coils are locked and ensnaring into the stent has occurred.11 Some authors suggested that the tines of the Neuroform3 stent with its open-cell design are fairly rigid and sharp, and this could be problematic.9 However, there is no literature about rupture using this technique with the Neuroform3 stent. The closed-cell design allows for retrieval of partially or fully deployed stents, thereby improving precise positioning. An advantage of a closed-cell design stent over the Neuroform3 stent is its flexible closed-cell design, which allows it to be retrieved and repositioned.8,15 The flared ends of the stent remodeled the aneurysm neck by conforming to the shape of the neck without any technical difficulty, resulting in a stable scaffold holding the coils into the aneurysm.8 Also, the Solitaire AB stent has some advantages in comparison to conventional self-expanding microstents since the delivery via the Rebar 18 microcatheter does not need distal wire purchase.9,15 A downside to the closed-cell design stent is that the closed-cell design may limit blood flow from the parent artery through the stent tube into the branching arteries where it covers them at their origins, and the open cell-design of the Neuroform3 stent would theoretically minimize these potential complications.8

Conclusion

We think that the waffle-cone technique is useful for carefully selected aneurysm morphologies consistent with long dome heights and wide necks that incorporate the bifurcating vessels.

Funding

This work was supported by the research fund of Dankook University in 2013.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Liu W, Kung DK, Policeni B, et al. Stent-assisted coil embolization of complex wide-necked bifurcation cerebral aneurysms using the “waffle cone” technique. A review of ten consecutive cases. Interv Neuroradiol 2012; 18: 20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz M, Levy E, Sauvageau E, et al. Intra/extra-aneurysmal stent placement for management of complex and wide-necked- bifurcation aneurysms: Eight cases using the waffle cone technique. Neurosurgery 2006; 58(4 Suppl 2): ONS-258–262. discussion ONS-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho JS, Kim YJ. Modified ‘y-configured stents with waffle cone technique’ for broad neck basilar top aneurysm. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2011; 50: 517–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahal JP, Dandamudi VS, Safain MG, et al. Double waffle-cone technique using twin Solitaire detachable stents for treatment of an ultra-wide necked aneurysm. J Clin Neurosci 2014; 21: 1019–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordhan AD. Intraaneurysmal neuroform stent implantation with compartmental dual microcatheter coil embolization: Technical case report. J Neuroimaging 2010; 20: 277–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mpotsaris A, Henkes H, Weber W. Waffle Y technique: pCONus for tandem bifurcation aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: e51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raymond J, Guilbert F, Weill A, et al. Long-term angiographic recurrences after selective endovascular treatment of aneurysms with detachable coils. Stroke 2003; 34: 1398–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padalino DJ, Singla A, Jacobsen W, et al. Enterprise stent for waffle-cone stent-assisted coil embolization of large wide-necked arterial bifurcation aneurysms. Surg Neurol Int 2013; 4: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sychra V, Klisch J, Werner M, et al. Waffle-cone technique with Solitaire AB remodeling device: Endovascular treatment of highly selected complex cerebral aneurysms. Neuroradiology 2011; 53: 961–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang TH, Wong HF, Yang MS, et al. “Waffle cone” technique for intra/extra-aneurysmal stent placement for the treatment of complex and wide-necked bifurcation aneurysm. Interv Neuroradiol 2008; 14(Suppl 2): 49–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu SW, Chaloupka JC, Fujitsuka M. In vitro studies for stent-assisted coiling of terminus aneurysms by straight-on intra-aneurysmal stent deployment. World Neurosurg 2013; 80: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauck EF, Natarajan SK, Hopkins LN, et al. Salvage Neuroform stent-assisted coiling for recurrent giant aneurysm after waffle-cone treatment. J Neurointerv Surg 2011; 3: 27–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu F, Qin X, Tian Y, et al. Endovascular treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms using intra/extra-aneurysmal stent. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011; 153: 923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo XB, Yan BJ, Guan S. Waffle-cone technique using Solitaire AB stent for endovascular treatment of complex and wide-necked bifurcation cerebral aneurysms. J Neuroimaging 2014; 24: 599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park HR, Yoon SM, Shim JJ, et al. Waffle-cone technique using Solitaire AB stent. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2012; 51: 222–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]