Abstract

Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVFs) with perimedullary drainage represent a rare subtype of intracranial dAVF. Patients usually experience slowly progressive ascending myelopathy and/or lower brainstem signs. We present a case of foramen magnum dural arteriovenous fistula with an atypical clinical presentation. The patient initially presented with a generalised tonic-clonic seizure and no signs of myelopathy, followed one month later by rapidly progressive tetraplegia and respiratory insufficiency. The venous drainage of the fistula was directed both to the left temporal lobe and to the perimedullary veins (type III + V), causing venous congestion and oedema in these areas and explaining this unusual combination of symptoms. Rotational angiography and overlays with magnetic resonance imaging volumes were helpful in delineating the complex anatomy of the fistula. After endovascular embolisation, there was complete remission of venous congestion on imaging and significant clinical improvement. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a craniocervical junction fistula presenting with epilepsy.

Keywords: Dural arteriovenous fistula, perimedullary drainage, myelopathy, epilepsy

Introduction

Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas (dAVFs) with perimedullary venous drainage represent a rare subtype of dAVF. Because of the variable and misleading nature of presenting signs, the diagnostic is often delayed.

We present a case with atypical initial presentation consisting of a generalised tonic-clonic seizure without any signs of cervical myelopathy. The anatomy of the fistula was delineated using rotational angiography and overlays with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) volumes. The importance of the venous drainage pattern is discussed, in relation with the clinical symptoms.

Case description

A 38-year-old male was admitted to our intensive care unit; 28 days before he had presented a generalised tonic-clonic seizure. Brain computed tomography was interpreted as normal and an electroencephalogram showed left temporal focal epileptiform discharges; he was started on levetiracetam and discharged awaiting further work-up. 20 days later he was readmitted for rapidly progressive paraparesis and acute urinary retention. Lumbar spine MRI, lumbar puncture, nerve conduction studies, and electromyography were negative for Guillain–Barré syndrome. However, under this working hypothesis, he was started on methylprednisolone and subsequently the symptoms significantly improved. He was discharged, but on the same day he collapsed and lost consciousness.

On examination, the patient was conscious, on artificial ventilation, there was tetraplegia with abolished reflexes and T4 sensory level. Brain and cervical MRI (Figure 1), and subsequently a cerebral angiogram (Figure 2) confirmed the diagnosis of foramen magnum dAVF with venous oedema in the left temporal lobe and the cervical cord (type III plus V according to the Lariboisière classification).1 The fistulous point is located on the right posterior border of foramen magnum (Figure 2(d)). The arterial feeders consist of a main branch of the right occipital artery and a smaller branch issued from the posterior trunk of the right ascending pharyngeal artery (Figure 2(a)). There is a unique long and tortuous draining vein with bi-directional drainage towards the spinal veins and towards a left cortical temporal vein. The anatomy of the venous drainage is detailed in Figure 2.

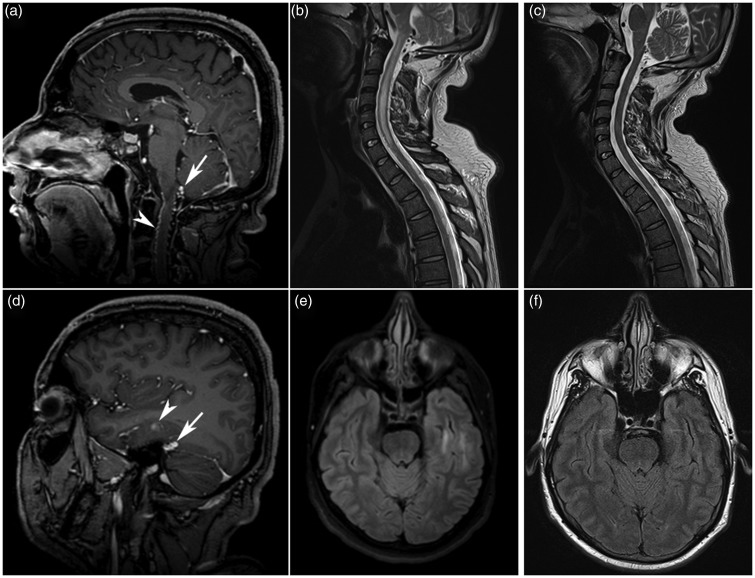

Figure 1.

Pre- and post-treatment MRI. (a,b,d,e) Initial cerebral and cervical MRI. Midline cerebral sagittal T1 sequence (a) after injection of contrast, showing an abnormally dilated vein posterior to the medulla oblongata (arrow) as well as dilated and tortuous anterior and posterior spinal veins (arrow head). Cervical sagittal T2 (b) sequence showing a hyperintense central cord lesion extending from the medulla oblongata to C7, in keeping with venous oedema. Cerebral post-contrast sagittal T1 sequence (d) and axial FLAIR sequence (e) showing a dilated vein at the junction of tentorium with the superior petrosal sinus (arrow), coursing across the inferior temporal sulci (arrow head), with a surrounding area of high FLAIR signal. (c,f) Cerebral and cervical MRI 13 days after embolisation. Cervical sagittal T2 sequence (c) and cerebral axial FLAIR sequence (f) showing complete resolution of temporal lobe and cervical cord venous oedema.

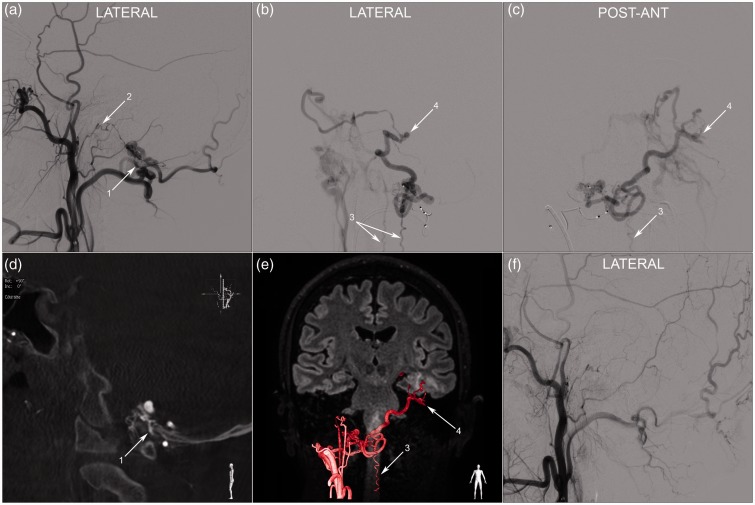

Figure 2.

Angiography during embolisation. (a) Right external carotid injection, early arterial phase, showing a right sided foramen magnum dural arteriovenous fistula fed by the occipital artery (1) and the posterior trunk of the ascending pharyngeal artery (2). A microcatheter was navigated distally into the occipital artery feeder and a selective injection was performed: the lateral (b) and postero-anterior (c) projections demonstrate the venous drainage pattern. There is a single long and tortuous draining vein. It passes posterior to medulla oblongata, drains into the anterior and posterior spinal veins (3) then crosses the midline and goes up to the left tentorium through the cerebellopontine angle. There is a change of calibre and an aneurysmal dilatation (4) as it crosses at the junction between the tentorium and the superior petrosal sinus, then it courses along the inferior face of the left temporal lobe (cortical temporal vein) to drain in the left cavernous sinus. (d) Right paramedian sagittal MIP reconstruction of a rotational angiography during injection of the right external carotid. A branch of the right occipital artery (1) passes between the atlas and the occipital bone to feed the foramen magnum fistula. The fistulous point is located on the right posterior border of foramen magnum. (e) Anatomical overlay of the rotational angiography and MRI 3D FLAIR sequence using the Philips™ post-processing workstation. The trajectory of the draining vein is delineated across anatomical and parenchymal landmarks. (f) Post-embolisation right external carotid injection, lateral projection, showing complete occlusion of the fistula.

Endovascular embolisation was performed on the same day. A detachable microcatheter was navigated distally into a feeder branch from the occipital artery and the initial portion of the draining vein was occluded using Onyx-18™ (Ev3 Neurovascular, California).

Post-operatively, there was a rapid improvement of neurological symptoms. Brain and spine MRI performed 13 days post embolisation showed disappearance of cervical and left temporal lobe venous oedema.

The patient was discharged to a rehabilitation centre. Two months later he was readmitted for worsening of the motor deficit in the inferior limbs occurring over a few days. Cervical MRI showed oedema of the cervical cord and he was treated on the same day for recurrence of the dural fistula. The same materials were used to occlude two small arterial feeders originating from the right vertebral and occipital arteries.

At 6 months follow-up, cervical and brain MRI show complete exclusion of the fistula and absence of cervical cord oedema or atrophy. The antiepileptic medication was stopped without recurrence of seizures. He can walk without help for short distances using two crutches; there is residual 4/5 motor deficit of the right upper and lower limbs, especially for plantar dorsiflexion, superficial sensory deficit in the right limbs, occasional urinary retention and erectile dysfunction.

Discussion

Intracranial dAVFs with perimedullary venous drainage are rare. A recent paper published in 2013 identified 58 cases reported in the literature.2 There was a male predominance and the average age was 56.5 years. As for all intracranial dAVFs, the aetiology remains unclear; it is considered an acquired pathology, with venous sinus thrombosis advocated as a precursor mechanism in some cases.2

Most patients present with ascending para/tetraplegia and sphincter disturbances.2–8 Involvement of the brainstem can lead to dysautonomic disturbances, lower cranial nerve signs and respiratory insufficiency. The symptoms can be acute/subacute in up to 57% of cases.2 More rarely, the fistula is diagnosed after a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH).

Possible localisations of the arteriovenous fistulous point include the cavernous sinus, tentorium, superior petrosal sinus, sigmoid/transverse sinus, hypoglossal canal and foramen magnum. The venous drainage pattern is the most important factor that influences the clinical presentation.1,9 The venous anatomy of the posterior fossa explains why remote arteriovenous shunts can cause cervical and thoracic myelopathy. The anterior and posterior spinal veins communicate with the anterior and posterior medullary veins and further with the medullo-pontine, pontomesencephalic and petrosal veins.2

An interesting demonstration of these anastomotic pathways is seen in our case, in which the venous drainage had a particular bidirectional configuration, explaining the association of seizure and myelopathy (Figure 2):

First, the fistula drained inferiorly towards the spinal veins, with contrast descending to the inferior thoracic cord, where it stagnated and no drainage was visualised towards the epidural veins. This induced venous congestion and oedema in the cervical cord.

Second, the fistula drained superiorly through the pontomesencephalic veins towards the left superior petrosal sinus and then through a temporal cortical vein towards the left cavernous sinus. This induced left temporal venous congestion and explains the left temporal focal discharges and the tonic-clonic seizure.

These venous connections around the medulla oblongata represent dilatations of pre-existing anastomoses. The fistulous vein is the right lateral medullo-pontine vein, which anastomoses with the anterior medullary vein and the posterior median vein of the medulla. These are continued inferiorly with the anterior and posterior medullary veins. Contralateral anastomoses ensure communication with the left medullo-pontine vein that drains into the superior petrosal sinus.

Although complex venous drainage is common for this type of fistula, we did not identify another case in the literature with both myelopathy and symptomatic supra-tentorial venous congestion. In a series of 12 patients,3 6 presented with myelopathy, 5 with SAH and 1 with transient aphasia. In all cases without myelopathy, an effective venous exit pathway was observed in the cervical cord towards the epidural veins. None of the cases associated both types of symptoms.

In order to understand the complex anatomy, we performed a rotational angiography during injection of the right external carotid artery. Because of delayed filling in the long and tortuous draining vein, we injected 24 ml of contrast at a rate of 3 ml/s, with 3 seconds acquisition delay. The resulting reconstruction allowed for complete visualisation of the feeding arteries and the draining vein in a tri-dimensional model. Moreover, thin maximum intensity projection (MIP) reconstructions of the same volume can demonstrate the relationship with surrounding bone landmarks (Figure 2(d)). In our case, the fact that the main feeding branch passed directly between C1 and the occipital bone was predictive for easy catheterisation, in the absence of trans-osseous passage. Finally, the anatomical overlay with a MRI fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) volume (Figure 2(e)) can visualise the fistulous vessels across parenchymal structures.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we present a case of foramen magnum dural arteriovenous fistula with an atypical venous drainage pattern that induced an association of generalised epileptic seizure and cervical myelopathy. Rotational angiography and overlays with MRI volumes can be helpful in delineating the anatomy of complex dural fistulas.

Ethical standards and patient consent

This is a retrospective report of a procedure performed as part of usual patient care according to local institutional protocols. All presented data are anonymised and the patient gave an informed consent.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Cognard C, Gobin YP, Pierot L, et al. Cerebral dural arteriovenous fistulas: clinical and angiographic correlation with a revised classification of venous drainage. Radiology 1995; 194: 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Asri AC, El Mostarchid B, Akhaddar A, et al. Factors influencing the prognosis in intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas with perimedullary drainage. World Neurosurg 2013; 79: 182–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunereau L, Gobin YP, Meder JF, et al. Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas with spinal venous drainage: relation between clinical presentation and angiographic findings. Am J Neuroradiol 1996; 17: 1549–1554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mascalchi M, Scazzeri F, Prosetti D, et al. Dural arteriovenous fistula at the craniocervical junction with perimedullary venous drainage. Am J Neuroradiol 1996; 17: 1137–1141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ricolfi F, Manelfe C, Meder JF, et al. Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulae with perimedullary venous drainage. Anatomical, clinical and therapeutic considerations. Neuroradiology 1999; 41: 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, Beute GN. Intracranial dural fistulas with exclusive perimedullary drainage: the need for complete cerebral angiography for diagnosis and treatment planning. Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 348–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang G, Gao X, Li Z, Wang X, et al. Endovascular treatment for dural arteriovenous fistula at the foramen magnum: report of five consecutive patients and experience with balloon-augmented transarterial Onyx injection. J Neuroradiol 2013; 40: 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spittau B, Millan DS, El-Sherifi S, et al. Dural arteriovenous fistulas of the hypoglossal canal: systematic review on imaging anatomy, clinical findings, and endovascular management. J Neurosurg 2015; 122: 883–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borden JA, Wu JK, Shucart WA. A proposed classification for spinal and cranial dural arteriovenous fistulous malformations and implications for treatment. J Neurosurg 1995; 82: 166–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]