Abstract

This study shows the frequency and types of carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF) complications that occurred during endovascular treatment. Transarterial endovascular surgeries involving the anterior circulation were performed for 1071 cases at our hospitals during four years. CCFs occurred in nine of 1071 cases (0.8%). CCF risk factors were female sex (p = 0.032), aneurysmal location in the paraclinoid portion (p < 0.001), and use of a distal access catheter (DAC) (p < 0.001). There were no significant correlations between CCF risk and procedure type (p = 0.411–1.0) and balloon use or nonuse (p = 0.492). Eighty-nine percent (eight of nine) of the CCFs occurred at the genu of a cavernous internal carotid artery (ICA). Two cases of CCF disappeared spontaneously. The shunt was decreased by balloon expansion in one case, no additional treatment was required in one case, and five cases required transarterial fistula coil embolization. It is necessary to remember that a CCF may occur especially in aneurysmal treatment using a DAC in a female patient. The DAC and the 0.035-inch guidewire should be kept proximal to the carotid siphon and not go beyond it. When we cannot avoid navigating beyond it, we should consider using a softer DAC. In the case of a CCF caused by a DAC, it may be cured spontaneously or is treatable by transarterial coil embolization.

Keywords: Carotid-cavernous fistula, complication, catheter intervention, distal access catheter

Introduction

A direct carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF) usually occurs from trauma or aneurysmal rupture; it is rarely iatrogenic.1 Iatrogenic CCFs may be due to trans-sphenoidal surgery,2,3 Fogarty catheter thromboendarterectomy,4 intracranial percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA),5–7 or embolization of tumor vessels.8 It has been reported that a vascular complication occurred in 1.2% of 1200 interventional procedures. The affected vessels were cortical branches, perforating arteries, and veins,9 and only two cases of a CCF during catheter navigation appear to have been reported in one paper.10 The purpose of this study was to determine the frequency and types of CCF complications that occurred during endovascular treatment in our institution.

Materials and methods

From May 2011 through April 2015, 1533 catheter interventions for intracranial vessels were performed at the Juntendo University Hospital and affiliated hospitals. The following cases were excluded: 290 cases involving posterior circulation arteries, 64 cases involving the external carotid artery, nine cases of traumatic or idiopathic CCF, and 99 cases of dural arteriovenous fistula. Therefore, transarterial endovascular surgeries involving the anterior circulation were performed for 1071 cases. CCF cases occurring during primary disease treatment were selected using our operation record database. CCF risk factors were tested using Fisher’s exact test. Statistical analyses were performed with the free statistics software EZR (Easy R).11

Results

CCFs occurred in nine of 1071 cases (0.8%). All cases were women, and the average age was 66 (45–81) years. The incidence of CCF was 0.96% (six of 622 cases) during coil embolization for non-ruptured aneurysm, 0.67% (two of 297 cases) during coil embolization of ruptured aneurysms, and 2.5% (one of 40 cases) during intra-arterial injection/PTA for vasospasm. There were no cases during 56 mechanical thrombectomies, 35 arteriovenous malformation (AVM) embolizations, or 21 intracranial PTAs. In aneurysmal cases with CCFs, the aneurysms were all located in the paraclinoid portion. Six cases occurred during navigation of a 4-French (F) distal access catheter (DAC) using a 0.035-inch guidewire with the catheter-assist technique. Two cases occurred during balloon catheter navigation, and one case occurred after balloon-assist coil embolization. The locations of the fistulas were the anterior ascending/horizontal segment of a cavernous internal carotid artery (ICA) in three cases, the horizontal segment in one case, and the posterior ascending/horizontal segment in five cases. Six cases of CCF occurred during catheter navigation for aneurysmal coil embolization. Aneurysmal embolization continued in four cases, and CCF treatment proceeded in two cases. Two cases of CCF disappeared spontaneously. The shunt was decreased by balloon expansion in one case (angiogram 11 days later showed that the CCF had disappeared), no additional treatment was required in one case, and five cases required transarterial fistula coil embolization. The average coil number was six (1–12), and the average length of CCF embolization was 19 (2–37) cm (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and radiological characteristics of nine cases with a direct CCF occurring during neurointerventional procedures.

| Case | Sex | Age | Disease | Procedure | Catheter navigation | Location of fistula | CCF timing | Treatment order | Treatment method of CCF | Coil (number, length) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 74 | Ruptured IC-ant choroidal AN | Coil embolization | 4F DAC/guidewire | Post ascending/horizontal seg | After AN embolization | Balloon inflation | ||

| 2 | F | 74 | Non-ruptured paraclinoid (cavernous) AN | Coil embolization | 4F DAC/guidewire | Horizontal seg | Pre-AN embolization | AN coiling→CCF TAE | TAE | 1, 2 cm |

| 3 | F | 68 | Non-ruptured paraclinoid (cavernous) AN | Coil embolization | 4F DAC/guidewire | Ant ascending/horizontal seg | Pre-AN embolization | AN coiling | Spontaneous remission | |

| 4 | F | 45 | Non-ruptured paraclinoid (ophthalmic) AN | Coil embolization | Balloon/guidewire | Post ascending/horizontal seg | Pre-AN embolization | AN coiling→CCF TAE | TAE | 12, 37 cm |

| 5 | F | 81 | Non-ruptured paraclinoid (cave) AN | Coil embolization | 4F DAC/guidewire | Post ascending/horizontal seg | Pre-AN embolization | AN coiling | No treatment | |

| 6 | F | 52 | Non-ruptured paraclinoid (cave) AN | Coil embolization | 4F DAC/guidewire | Post ascending/horizontal seg | During AN embolization | CCF TAE→AN coiling | TAE | 7, 15 cm |

| 7 | F | 69 | Non-ruptured paraclinoid (cave) AN | Coil embolization | 4F DAC | Post ascending/horizontal seg | Pre-AN embolization | CCF TAE→AN coiling | TAE | 3, 6 cm |

| 8 | F | 50 | Ruptured paraclinoid (anterior wall) AN | Coil embolization | Balloon assisted | Ant ascending/horizontal seg | After AN embolization | Spontaneous remission | ||

| 9 | F | 77 | Vasospasm after SAH | PTA | Balloon/guidewire | Ant ascending/horizontal seg | TAE | 9, 36 cm |

CCF: carotid-cavernous fistula; IC: internal carotid; AN: aneurysm; PTA: percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; DAC: distal access catheter; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; TAE: transarterial embolization; F: female; ant: anterior; post: posterior; seg: segment.

CCF risk factors were as follows: female sex (p = 0.032), aneurysmal location in the paraclinoid portion (in 919 cases of aneurysmal treatment) (p < 0.001), and use of a DAC (p < 0.001). There were no significant correlations between CCF risk and procedure type (aneurysm coiling, intra-arterial injection/PTA, mechanical thrombectomy, AVM embolization) (p = 0.411–1.0) and balloon use or nonuse (p = 0.492) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relationships between various factors and CCFs.

| CCF | + | − | p | Odds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Female | 0/9 | 371/691 | 0.032 | 0 |

| AN coiling/other IVR | 8/1 | 911/151 | 1 | 1.33 |

| Intracranial PTAċIA/ other IVR | 1/8 | 60/1002 | 0.411 | 2.09 |

| Mechanical thrombectomy/other IVR | 0/9 | 56/1006 | 1 | 0 |

| AVM embolization/other IVR | 0/9 | 35/1027 | 1 | 0 |

| IC paraclinoid/other location | 7/1 | 229/682 | <0.001 | 20.8a |

| Catheter-assisted/other technique | 6/2 | 70/841 | <0.001 | 35.7a |

| Balloon-assisted/other technique | 2/6 | 358/553 | 0.492 | 0.52a |

In 919 aneurysmal treatments. CCF: carotid-cavernous fistula; AN: aneurysm; PTA: percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; IA: intra-arterial; AVM: arteriovenous malformation; IVR: interventional radiology; IC: internal carotid.

Representative case

A 52-year-old woman was to undergo coil embolization for a non-ruptured left ICA paraclinoid (cave) aneurysm, 5 mm × 6 mm. An Axcelguide 6F 80 cm STR (Medikit Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the left ICA as a guiding sheath, and a Cerulean DD6 105 cm (Medikit Co., Ltd) was advanced to around the ICA siphon. An attempt was made to perform coil embolization using the balloon-assist technique, but the microcatheter was unstable. Next, a Cerulean G40 125 cm (Medikit Co., Ltd) was advanced to the aneurysmal neck coaxially. Coil embolization was started through a HeadWay 17 STR 2M (MicroVention Terumo, Tustin, CA, USA). After three 30-cm coils were used, a Cerulean G40 deviated into the ICA. After trying to insert into the neck of the aneurysm a RADIFOCUS 0.035 150 cm angle E type (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) into the neck of the aneurysm, angiogram showed a CCF with visualization of the superior ophthalmic vein and contralateral cavernous sinus. There was no cortical venous reflux (Figure 1(a), (b)). Heparinization was reversed by protamine. A Scepter C 4 × 10 mm (MicroVention Terumo) was inflated at the fistula to reduce blood flow, but the CCF thrombus did not progress. The combination of a HeadWay 17 STR/RADIFOCUS Guide Wire M 0.012 double angle (Terumo, Tokyo) was inserted into the fistula through a Cerulean DD6. Seven coils were used, for a total of 15 cm, under balloon-assist (Figure 2(a), (b)). After the shunt disappeared, aneurysmal coil embolization was resumed and finished to complete embolization (Figure 3).

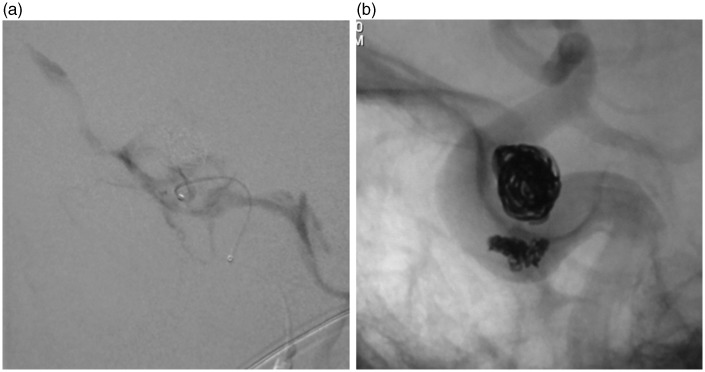

Figure 1.

(a) Frontal and (b) lateral views of a left internal carotid artery (ICA) angiogram showing a carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF) with simultaneous visualization of the cavernous sinus.

Figure 2.

(a) Lateral angiogram shows the microcatheter inserted into the fistula. Microcatheter injection allows visualization of the carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF). (b) Fluoroscopic view shows coils in the fistula and aneurysm.

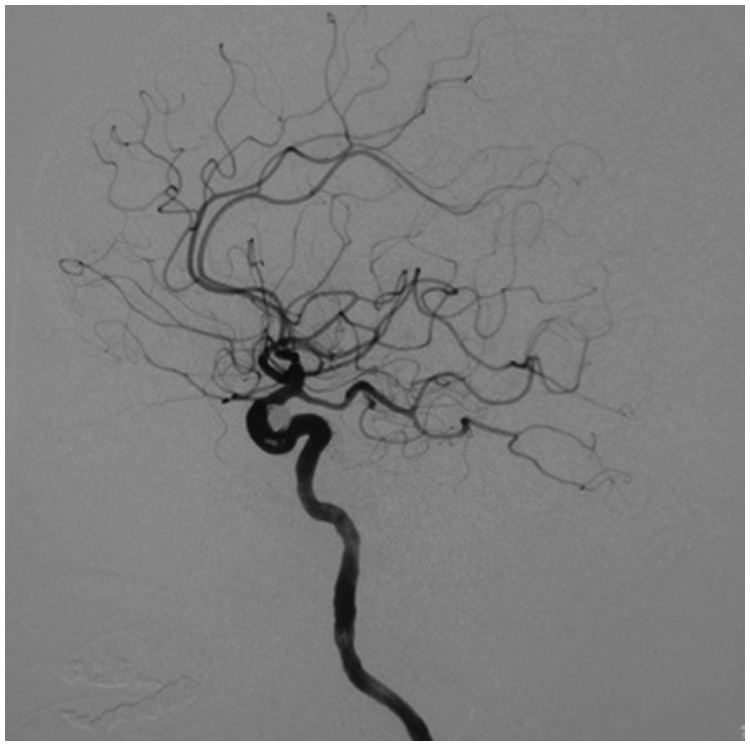

Figure 3.

Lateral view of the internal carotid artery (ICA) following coil embolization showing complete carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF) obliteration.

Discussion

CCF complications occurred in 0.8% of cases in this relatively large number of cases. This complication occurred significantly more in women during paraclinoid aneurysm treatment using DAC. It has been reported that cortical branch injury occurred in four of 459 cases (0.87%) during coil embolization of an aneurysm.12 They mentioned that vascular injury should be considered when navigating a guidewire/microcatheter to a distal vessel.

CCFs occurred significantly more in women, suggesting a sex difference in vascular weakness. However, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which can be a risk factor for CCF,13 was not found in these patients. The catheter system using DAC affords distal support and stability for the microcatheter during endovascular therapeutic interventions.14,15 The complication rate with DAC use was low, 0 of 10314 or 0 (one thromboembolism) of 18 aneurysm treatments.15 However, the rate of CCF was high, 7.1%–7.9% (six of 76 aneurysm treatments, six of all 85 procedures with DAC use), in this study. The following factors might be responsible. When a paraclinoid aneurysm is treated, it is easy for the microcatheter to become unstable. We tended to choose a catheter-assist technique using a DAC rather than a balloon-assist in this situation, and we tried to advance the DAC as close to the target lesion as possible. The high rate of CCF complications is likely due to guiding the DAC and 0.035-inch guidewire too distally in the carotid artery. Though it was placed as close as possible to the target aneurysm, within 1.5–2.5 cm, there was no CCF.15 They used a DAC initially designed to assist the Merci device with clot retrieval, which is manufactured with outer diameters of 3.9 and 4.3 F.14,15

When the 054 Penumbra catheter, which is larger than a 4F DAC in size, that was used in this study was advanced to the intracranial occluded vessel during mechanical thrombectomy, vessel dissection occurred in two of 98 cases (2%), and vessel perforation was recognized in two of 87 cases (2.3%).16,17 However, there were no cases of CCF. This may be explained as follows. A 3.8F catheter was used coaxially to reduce the ledge effect of the Penumbra catheter.18 A DAC for catheter stability as used in this series might be stiffer than a DAC designed to assist a clot retrieval or thrombus aspiration device, so it might not be suitable to exceed the carotid siphon.

In this study, the fistulas were located at the junction of the anterior ascending/horizontal segment of the ICA in three cases and the posterior ascending/horizontal segment in five cases; 89% (eight of nine) of the CCFs occurred at the genu of a cavernous ICA. The guidewire or DAC seemed to be more likely to directly perforate at the curved portion of the ICA rather than penetrating the meningohypophyseal trunk (MHT), which usually arises from the posterior ascending/horizontal segment portion of the ICA. A previous report noted that fistulas were positioned at the posterior part of the cavernous ICA in two perforation cases during catheter navigation; they suggested that this may be related to the acutely angled vasculature in this region.10

A direct CCF is treated by transarterial, transvenous, or direct venous puncture. Chi et al. found that, when a fistula was small, 21/22 cases were treatable by transarterial coil embolization only.19 Iatrogenic CCFs are treated by the transarterial route8,9 using a stent.4,6 When symptoms are subclinical and flow is not high, spontaneous obstruction is rarely possible,6,10 as in the present three cases. When a CCF occurs before treatment of the primary disease, which disease needs to be treated first may depend on shunt flow.

It is necessary to remember that a CCF may occur during catheter navigation, especially in aneurysmal treatment using a DAC in a female patient; therefore, the DAC and the 0.035-inch guidewire should be kept proximal to the carotid siphon and not go beyond it. When we cannot avoid navigating beyond it, we should consider using a softer DAC. In the case of a fistula caused by a guidewire/catheter, it may be cured spontaneously or is treatable by transarterial coil embolization.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Lewis AI, Tomsick TA, Tew JM., Jr Management of 100 consecutive direct carotid-cavernous fistulas: Results of treatment with detachable balloons. Neurosurgery 1995; 36: 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi M, Killeffer F, Wilson G. Iatrogenic carotid cavernous fistula. Case report. J Neurosurg 1969; 30: 498–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kocer N, Kizilkilic O, Albayram S, et al. Treatment of iatrogenic internal carotid artery laceration and carotid cavernous fistula with endovascular stent-graft placement. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2002; 23: 442–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eggers F, Lukin R, Chambers AA, et al. Iatrogenic carotid-cavernous fistula following Fogarty catheter thromboendarterectomy. Case report. J Neurosurg 1979; 51: 543–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SH, Qureshi AI, Boulos AS, et al. Intracranial stent placement for the treatment of a carotid-cavernous fistula associated with intracranial angioplasty. Case report. J Neurosurg 2003; 98: 1116–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Möllers MO, Reith W. Intracranial arteriovenous fistula caused by endovascular stent-grafting and dilatation. Neuroradiology 2004; 46: 323–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon WK, Kim YW, Kim SR, et al. Transarterial coil embolization of a carotid-cavernous fistula which occurred during stent angioplasty. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2009; 151: 849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barr JD, Mathis JM, Horton JA. Iatrogenic carotid-cavernous fistula occurring after embolization of a cavernous sinus meningioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995; 16: 483–485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Dowd CF, et al. Management of vascular perforations that occur during neurointerventional procedures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1991; 12: 319–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon HJ, Jin SC. Spontaneous healing of iatrogenic direct carotid cavernous fistula. Interv Neuroradiol 2012; 18: 187–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48: 452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryu CW, Lee CY, Koh JS, et al. Vascular perforation during coil embolization of an intracranial aneurysm: The incidence, mechanism, and clinical outcome. Neurointervention 2011; 6: 17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schievink WI, Piepgras DG, Earnest F, 4th, et al. Spontaneous carotid-cavernous fistulae in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Type IV. Case report. J Neurosurg 1991; 74: 991–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiotta AM, Hussain MS, Sivapatham T, et al. The versatile distal access catheter: The Cleveland Clinic experience. Neurosurgery 2011; 68: 1677–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauck EF, Tawk RG, Karter NS, et al. Use of the outreach distal access catheter as an intracranial platform facilitates coil embolization of select intracranial aneurysms: Technical note. J Neurointerv Surg 2011; 3: 172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frei D, Gerber J, Turk A, et al. The SPEED study: Initial clinical evaluation of the Penumbra novel 054 Reperfusion Catheter. J Neurointerv Surg 2013; 5(Suppl 1): i74–i76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turk AS, Frei D, Fiorella D, et al. ADAPT FAST study: A direct aspiration first pass technique for acute stroke thrombectomy. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo AJ, Frei D, Tateshima S, et al. The Penumbra Stroke System: A technical review. J Neurointerv Surg 2012; 4: 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chi CT, Nguyen D, Duc VT, et al. Direct traumatic carotid cavernous fistula: Angiographic classification and treatment strategies. Study of 172 cases. Interv Neuroradiol 2014; 20: 461–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]