Abstract

Flow diverter stents are new important tools in the treatment of large, giant, or wide-necked aneurysms. Their delivery and positioning may be difficult due to vessel tortuosity. Common adverse events include intracranial hemorrhage and ischemic stroke, which usually occurs within the same day, or the next few days after the procedure. We present a case where we encountered an unusual intracerebral complication several months after endovascular treatment of a large left internal carotid artery aneurysm, and where brain biopsy revealed foreign body reaction to hydrophilic polymer fragments distally to the stent site. Although previously described, embolization of polymer material from intravascular equipment is rare. We could not identify any other biopsy verified case in the literature, with this particular presentation of intracerebral polymer embolization – a multifocal inflammation spread out through the white matter of one hemisphere without hemorrhage or ischemic changes.

Keywords: Cerebral aneurysm, flow diverter stent, endovascular, cerebrovascular disease, foreign body reaction

Introduction

Flow diversion with self-expanding stents may be used to treat large wide-neck aneurysms, usually in the internal carotid artery,1,2 and with respect to this we have since 2009 used the Pipeline™ embolization device (PED) (Covidien). We present a patient with a complication that occurred several months after using a PED for the treatment of a large internal carotid artery aneurysm.

Case report

A 52-year-old Caucasian female with a history of psoriasis and hypertension presented to a local hospital with an episode of malignant hypertension. A routine head computed tomography (CT) scan including a CT angiography (CTA) revealed a wide-neck paraophthalmic aneurysm of the left internal carotid artery, measuring 11 × 11 × 8 mm3. Some months later, she underwent an elective stenting of the aneurysm using a PED. She started with dual antiplatelet therapy (clopidogrel 75 mg and acetylsalicylic acid 75 mg daily) one week before the intervention and continued after discharge. The procedure was performed without any complications, but the patient experienced a transient headache a few days later followed by reduced attention span, which affected her performance at work.

During the intervention procedure an Arrow 90 cm 6F introducer sheet (Teleflex Medical) was placed in the left common carotid artery. A Reflex 6 F intracranial catheter (Reverse Medical) 115 cm was used together with a DAC 044 distal access 4,3 F catheter (Concentric Medical) and a Marksman microcatheter (Covidien) to deliver the Pipeline stent (3.75 mm × 20 mm) (Covidien) in the left internal carotid artery. A hydrophilic guide – Terumo .035 guidewire (Terumo/Microvention) – and a Traxcess microwire (Microvention) were used for navigation.

Three months after the stenting procedure, still on dual antiplatelet therapy, she presented with an acute onset of global aphasia and right-sided hemiparesis and ataxia. The cerebral CT scan showed diffuse white matter edema frontally and parieto-occipitally in the left hemisphere (Figure 1). CTA showed obliteration of the aneurysm but no vessel occlusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed vasogenic edema in the same areas as on the CT, with sparing of the cerebral cortex (Figure 2). The areas with edema showed patchy contrast enhancement. There were neither signs of cytotoxic edema indicating ischemia nor any sign of inflammatory changes around the stent or the aneurysmal sac. A lumbar puncture was performed showing a leucocyte count of 3 white blood cells/mm3. The level of total protein was 0.71 g/L (normal range 0.15–0.55) and 0.45 when controlled. Glucose in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was 3.6 mmol/L and in plasma 6.2 mmol/L. Routine blood samples were normal and there were no clinical signs of infections. Infections such as fungi and TB were screened both clinically and in the CSF. Due to the prominent intracerebral edema, the patient was started on oral methylprednisolone at a dose of 16 mg four times daily. This led to major improvement of the symptoms the next days, with rapid regression of her ataxia and hemiparesis. Her speech was nearly fluent in a few days. On admission, her blood pressure was raised to 180/100 mmHg and her condition was at first thought to be an atypical presentation of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. MRI preformed one week after the initial admission, showed reduced contrast enhancement, but the extent of the white matter edema showed no apparent changes (Figure 3).

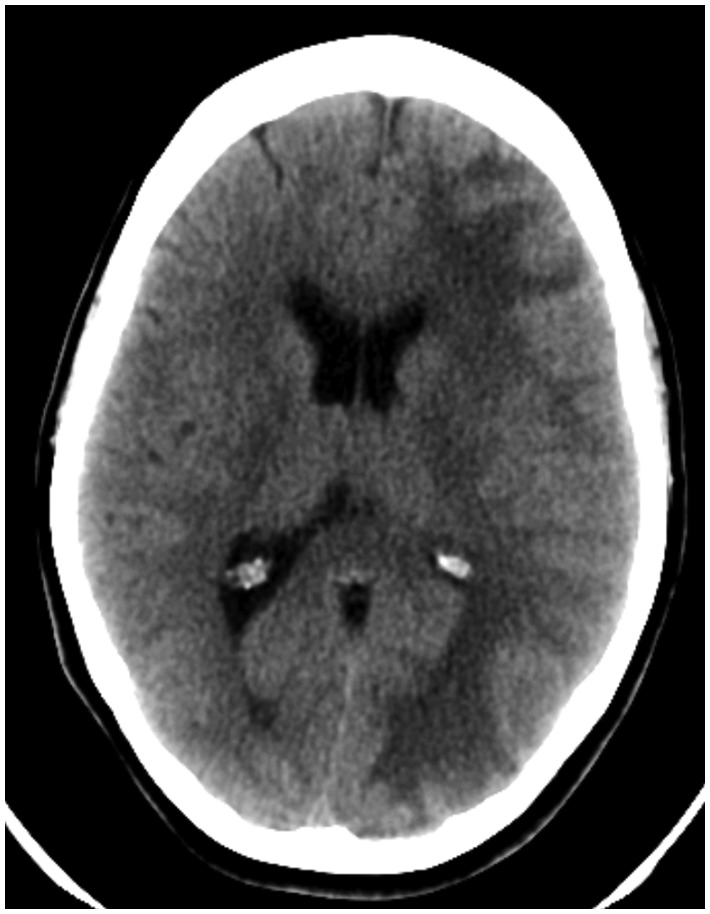

Figure 1.

Plain noncontrast head CT at initial admission three months after elective stenting of the left paraophthalmic aneurysm. The image shows a diffuse edema of the white matter of the ipsilateral hemisphere with a decreased demarcation of the sulci.

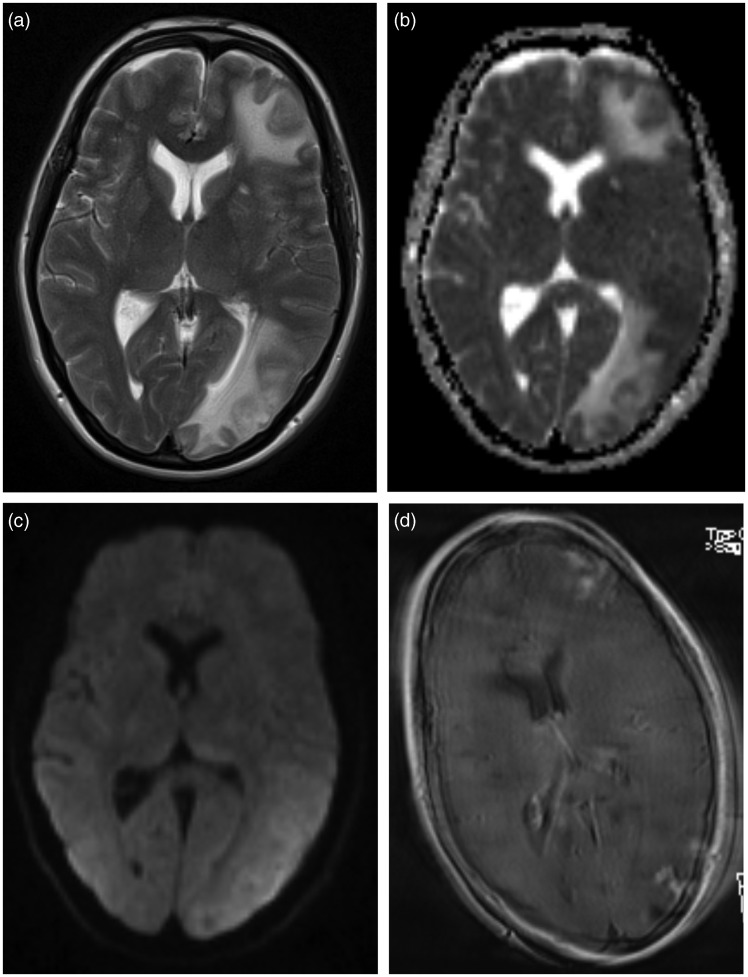

Figure 2.

Cerebral MRI performed immediately after the CT scan. T2-weighted sequence (a), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map (b), diffusion weighted sequence (c), and postgadolinium-T1 sequence (d). There is an increased signal on the T2-weighted sequence and increased diffusion on the ADC map, consistent with vasogenic edema in the white matter of the left hemisphere, most apparent frontally and parieto-occipitally. The patchy contrast enhancement is poorly visible due patient motion artifacts.

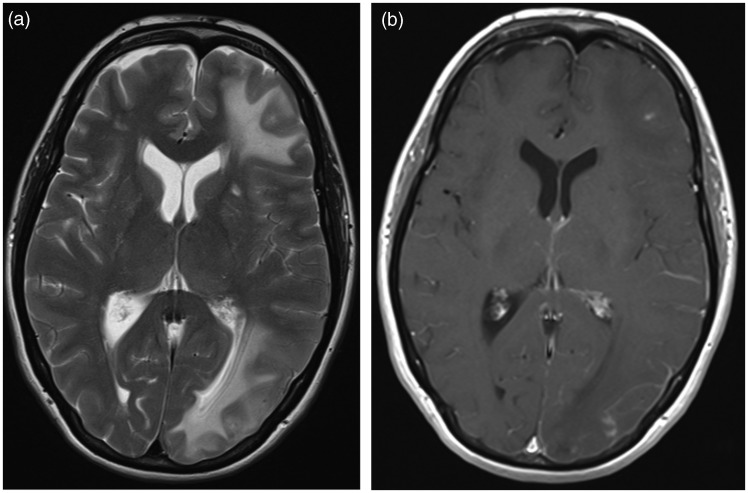

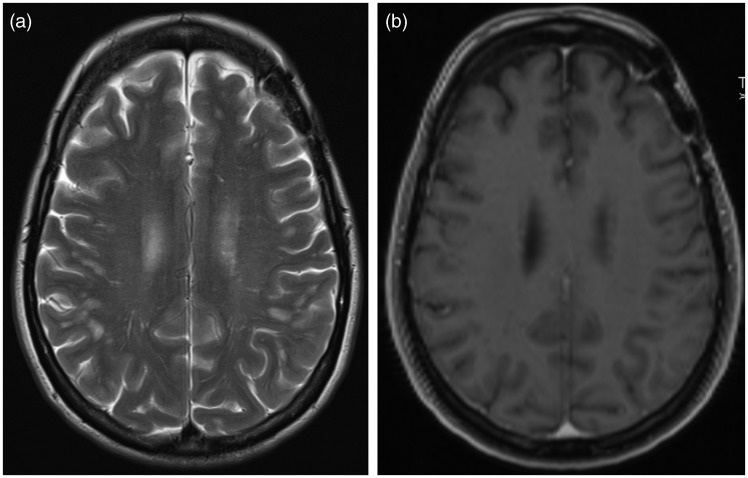

Figure 3.

T2-weighted (a) and postgadolinium-T1 (b) MRI one week later and after a course of high dose methylprednisolone, showing unchanged white matter edema on the T2 weighted sequence, but a significantly reduced contrast enhancement on the T1 sequence.

Methylprednisolone had a negative impact on the patient’s blood pressure, and this medication was discontinued after 4 weeks. By that time, her symptoms consisted of minimal paresis of the right hand and slight dizziness. A thorough investigation of the possible cause of hypertension yielded no results.

Shortly after discontinuation of methylprednisolone, she experienced recurring headaches. A repeat MRI showed further regression of the lesions previously seen, but new areas of contrast enhancement appeared at slightly different locations, although still in the left hemisphere (Figure 4). The MR-angiography showed no changes. A wide set of samples both in the serum and the CSF revealed no signs of pathogens, systemic autoimmune disease or malignancy.

Figure 4.

T2-weighted (a) and postgadolinium-T1 (b) MRI 3 months later and after discontinuation of methylprednisolone, showing a slight change in the distribution of the edema in the left hemisphere now appearing more cranially, with a corresponding increase in contrast enhancement.

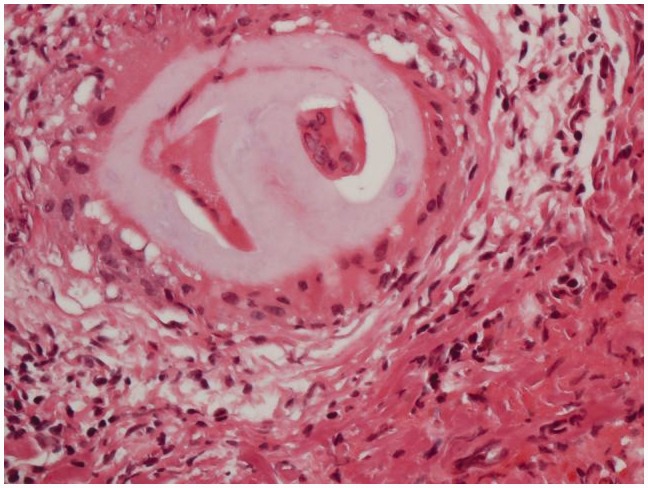

Four months after the initial acute presentation, a brain biopsy was performed through a left frontal craniotomy. Microscopic examination revealed a small meningeal vessel containing non-polarizable foreign material surrounded by multinucleated foreign-body type macrophages (Figure 5). The adjacent brain parenchyma contained a well-demarcated microabscess filled with neutrophilic granulocytes and multinucleated macrophages. Stainings for bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, toxoplasma and other microorganisms were negative. Immunohistochemical staining for beta-amyloid showed no sign of amyloid angiopathy. There was no sign of a neoplastic process. We concluded that this material most probably represented hydrophilic polymer fragments that had embolized to the peripheral vessels during the stenting procedure.

Figure 5.

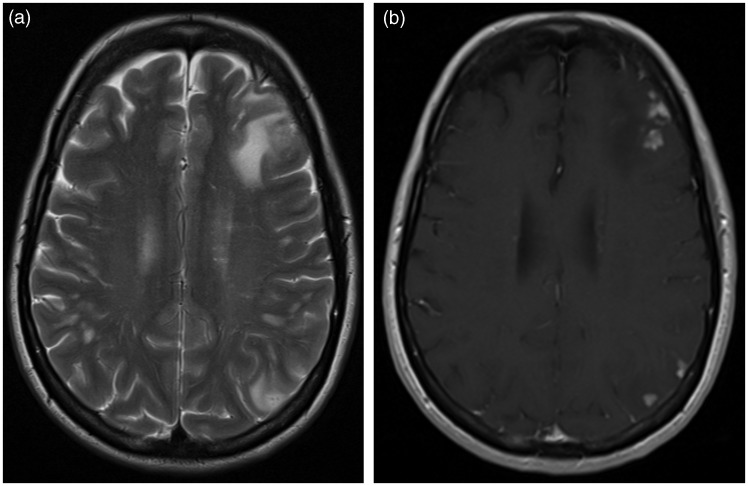

T2-weighted (a) and postgadolinium-T1 (b) MRI at 15 months of follow-up on a low dose of oral prednisone and azathioprine, showing a marked improvement and only a dural contrast enhancement frontally in the left hemisphere, at the site of the brain biopsy.

The patient was restarted on a lower dose of oral prednisone, in addition to azathioprine at a dose of 2 mg per kilogram body weight per day. She has tolerated this well so far and the condition has stabilized. The last MRI to date, taken 15 months after the first admission to our hospital, showed a substantial regression of the edema in the left hemisphere (Figure 6). The patient is currently still in follow-up. She has improved gradually, but is still on sick leave and is suffering from headache and fatigue.

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph of a hematoxylin and eosin stained sample of the frontal lobe showing a non-polarizable foreign material surrounded by multinucleated foreign-body type macrophage inside a small meningeal vessel. The adjacent brain parenchyma contains a well-demarcated microabscess filled with neutrophilic granulocytes and multinucleated macrophages.

Discussion

Catheters and wires used in intravascular procedures are coated with hydrophilic polymer materials to facilitate intravascular navigation, thus decreasing endothelial trauma and arterial spasm.3 There have been several reports of polymer embolization to various organs after intravascular procedures, such as cardiac catheterization, conventional angiography, central venous catheters and coiling of intracerebral aneurysms.3–9 In a recent case report with seven patients,10 MRI-enhancing brain lesions after endovascular therapy of aneurysms were described, although none of the patients underwent biopsy. The polymers can be identified by tissue biopsy. We were able to identify only 11 other patients in the literature with a biopsy-proven embolization intracranially. Seven of those patients died, two had persistent stroke symptoms, and in one case the status of the patient after identifying the foreign material was not described.3,5–7,11 The clinical presentation of the complications varied from one day to nine months following an intravascular procedure. Also, cases with foreign body reaction and biopsy-verified non-infections processes as complications of aneurysm coiling have been described.12

Our patient suffered neither stroke nor hemorrhage, but developed a diffuse inflammation in the white matter of the ipsilateral hemisphere. The treatment of the aneurysm was successful, with a complete occlusion of the aneurismal sac, and an open flow through the carotid. The inflammation appeared distally to the stent site. This suggests an embolization of the polymer coating in the area supplied by the internal carotid artery during the procedure.

Possibly, her hypertension could have contributed to the diffuse and widespread pattern of the inflammation, in terms of changes in the autoregulatory mechanisms in the brain that may have altered the cerebral perfusion. She also had a history of psoriasis, which hypothetically could have influenced the severe immune response to the foreign material. An endovascular procedure with deployment of flow diverter demands a high degree of stability in order to obtain a precise and secure delivery of the device. To achieve this it is customary to use triaxial or even quadraxial catheter technique. This can lead to increased friction between catheters and may predispose for small emboli from the coating of the catheters. Unfortunately, the specimen of foreign body material was insufficient to make cross testing and determine the origin of the material, though the diagnosis of foreign body material was indisputable.

In conclusion, although the embolization of the aneurysm was established and no acute severe complications appeared, this case report is a reminder that complication with foreign body reaction related to polymer embolization can occur after endovascular treatment. This is one of very few biopsy-verified cases in the literature with intracerebral polymer embolization and multifocal inflammation spread out through the white matter of one hemisphere without hemorrhage or ischemic changes.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Murthy SB, Shah S, Venkatasubba Rao CP, et al. Treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms with the pipeline embolization device. J Clin Neurosci 2014; 21: 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becske T, Kallmes DF, Saatci I, et al. Pipeline for uncoilable or failed aneurysms: results from a multicenter clinical trial. Radiology 2013; 267: 858–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta RI, Mehta RI, Choi JM, et al. Hydrophilic polymer emboli: an under-recognized iatrogenic cause of ischemia and infarct. Mod Pathol 2010; 23: 921–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta RI, Mehta RI, Choi JM, et al. Hydrophilic polymer embolism and associated vasculopathy of the lung: prevalence in a retrospective autopsy study. Hum Pathol 2015; 46: 191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta RI, Mehta RI, Fishbein MC, et al. Intravascular polymer material following coil embolization of a giant cerebral aneurysm. Hum Pathol 2009; 40: 1803–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fealey ME, Edwards WD, Giannini C, et al. Complications of endovascular polymers associated with vascular introducer sheaths and metallic coils in 3 patients, with literature review. Am J Surg Pathol 2008; 32: 1310–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu YC, Deshmukh VR, Albuquerque FC, et al. Histopathological assessment of fatal ipsilateral intraparenchymal hemorrhages after the treatment of supraclinoid aneurysms with the Pipeline embolization device. J Neurosurg 2014; 120: 365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denardo SJ, Carpinone PL, Vock DM, et al. Changes to polymer surface of drug-eluting stents during balloon expansion. JAMA 2012; 307: 2148–2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babcock DE, Hergenrother RW, Craig DA, et al. In vivo distribution of particulate matter from coated angioplasty balloon catheters. Biomaterials 2013; 34: 3196–3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz JP, Marotta T, O'Kelly C, et al. Enhancing brain lesions after endovascular treatment of aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 1954–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnwell SL, D'Agostino AN, Shapiro SL, et al. Foreign bodies in small arteries after use of an infusion microcatheter. Am J Neuroradiol 1997; 18: 1886–1889. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.König M, Bakke SJ, Scheie D, et al. Reactive expansive intracerebral process as a complication of endovascular coil treatment of an unruptured intracranial aneurysm: case report. Neurosurgery 2011; 68: E1468–E1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]