Summary

Inflammation induced during infection can both promote and suppress immunity. This contradiction suggests that inflammatory cytokines impact the immune system in a context-dependent manner. Here we show that non-specific bystander inflammation conditioned naïve CD4+ T cells for enhanced peripheral Foxp3 induction and reduced effector differentiation. This resulted in inhibition of immune responses in vivo via Foxp3-dependent effect on antigen-specific naïve CD4+ T cell precursors. Such conditioning may have evolved to allow immunity to infection while limiting subsequent autoimmunity caused by release of self-antigens in the wake of infection. Furthermore, this phenomenon suggests a mechanistic explanation for the concept that early tuning of the immune system by infection impacts the long-term quality of immune regulation.

Introduction

The adaptive immune system has evolved to provide effective long-term resistance to a wide range of microbial infections. However, the vigor of the immune response must be balanced by mechanisms that prevent damage to self-tissues. These mechanisms include intrinsic negative feedback pathways that “shut down” inflammatory signals1, 2, as well as mobilization of regulatory Foxp3+ T cells (Treg) that can suppress effector T cell (Teff) responses3. The peripheral differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into Foxp3+ Treg cells serves to enhance the functional capacity of the total Treg cellular pool by broadening the clonal repertoire4. This process critically limits immunopathology in tissues and at mucosal sites by induction of antigen-specific Treg cells that enforce tolerance to self-antigens or innocuous foreign antigens5. While peripheral development of Treg cells play an important role in immune tolerance overall, it is unclear how antigen-specific Treg cells from naïve CD4+ T cell precursors are modulated during the course of an acute inflammatory response such as viral infection.

Viral infection and immunostimulatory agents such as Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists promote T cell responses in part by production of cytokines6. Inflammatory cytokines and type I interferon (IFN-I) released by TLR stimulation enhance Teff cell responses and counter-act development and function of Treg cells that express the transcription factor Foxp37, 8, 9. TLR agonists such as the “viral mimic” polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (polyI:C) generate IFN-I inflammation, and are promising candidates to augment vaccination10. However, inflammatory cytokines also generate “bystander” signals to naïve T cells not specific for viral antigens11. This may act to breach activation thresholds for self-reactive T cells, supporting the notion that infection can trigger autoimmunity12, 13. In contrast, anti-viral inflammatory responses have been also shown to cause immunosuppression12, 14. This contradiction suggests that inflammatory cytokines may impact T cell responses in a flexible manner, the outcome being dependent on the context of T cell response.

Here we show that non-specific bystander inflammation conditions naïve CD4+ T cells for diminished effector response and enhanced induction of Foxp3 in response to subsequent antigen encounter. We refer to these T cells as inflammation-conditioned naïve T cells, or ICTN. The phenotypic change is directed by anti-viral inflammatory signals, and depends upon IFN-I signaling. Naïve CD4+ T cells exposed to IFN-I bystander inflammation exhibited altered molecular pathways that diminished Teff cell development to favor de novo Treg cell development from naïve CD4+ T cell precursors, thereby impacting subsequent antigen-specific immune responses. These data suggest that naïve CD4+ T cells integrate signals over time during an immune response to modulate effector/regulatory cellular responses over the course of inflammation.

Results

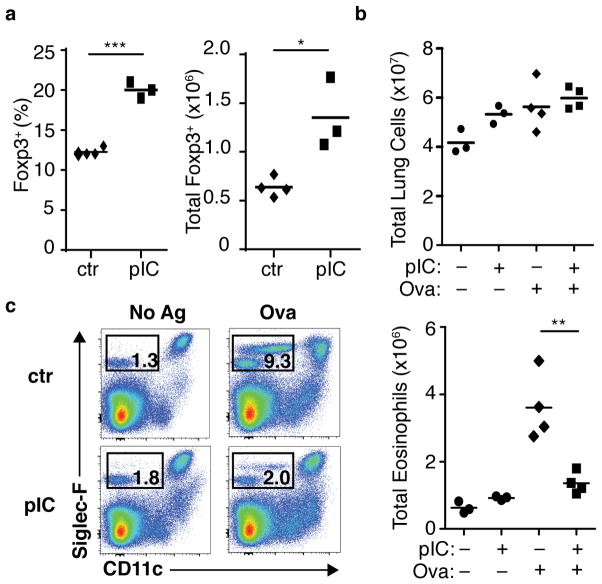

Inflammation increases Foxp3+ Treg cells and suppresses asthma

To determine the role of non-specific inflammatory stimuli on CD4+ T cells, we induced systemic inflammation by intraperitoneal injection of poly(I:C). Following this treatment, we observed a notable increase in frequency and total numbers of functional Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells in the spleen, peaking at approximately day 7 post-injection (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Foxp3+ Treg cells sorted from mice treated with poly(I:C) were similar to control cells with regard to in vitro functional suppressive activity and ex vivo phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 1b–d and data not shown), and did not produce inflammatory cytokines upon ex vivo restimulation (Supplementary Fig. 1e). When poly(I:C) was given directly to the pulmonary mucosa via intranasal delivery, increased frequencies and numbers of Foxp3+ Treg cells were observed in the lung (Fig. 1a). To determine how this nonspecific bystander inflammatory effect impacted a primary immune response in the mucosal environment, we adapted a model of antigen-specific priming via pulmonary mucosa following intranasal poly(I:C) treatment15 (see Materials and Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1f). All treatments resulted in a trend of elevated pulmonary cellular infiltration compared to PBS-treated negative controls (Fig. 1b). While primary antigen delivery resulted in eosinophil accumulation, as well as other measures of pulmonary inflammation in positive control mice, this response was completely inhibited following poly(I:C) pre-treatment (Fig. 1c). This effect was not due to skewing of lung infiltration toward a neutrophilic-based response (Supplementary Fig. 1g), indicating bystander inflammation acted to shut down, rather than qualitatively alter, the airway inflammatory response16.

Figure 1. Non-specific bystander inflammation results in increased Foxp3+ Treg cells and suppression of primary antigen-specific mucosal inflammatory response.

(a) Wild-type (WT) BALB/c mice were treated with poly(I:C) (pIC) or PBS (ctr) intranasally for two consecutive days. Seven days after the first treatment, frequency (left panel) and total number (right) of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells were assessed. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, data are representative of two independent experiments. (b–c) Primary antigen-specific pulmonary inflammation following intranasal poly(I:C) (described in Materials and Methods and Supplementary Fig. 1f). (b) Total pulmonary cell counts for mononuclear cells. (c) Pulmonary eosinophil infiltration, representative flow cytometry plots from indicated mice (left), total eosinophil counts for indicated mice (right). Each symbol represents an individual mouse, data representative of two independent experiments, n ≥ 6. Mice pre-treated with pIC (+) or PBS (−) and challenged with OVA–TSLP (+) or PBS (−) as indicated below the axis. P-values by student’s two-tailed t-test, * P <0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001.

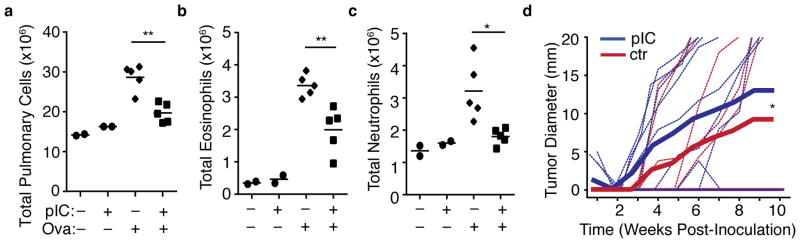

Immunization after inflammation diminishes recall response

We next tested the impact of systemic bystander inflammation on antigen-specific recall immune responses. Mice were treated with PBS or poly(I:C) via intraperitoneal injection, followed by immunization with subcutaneous Ovalbumin (OVA) emulsified in Incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA). The mice were then challenged with antigen 7–10 days later, either via the airways or with antigen-expressing tumor, and airway inflammation or tumor growth were assessed (see Materials and Methods and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Upon intranasal antigen challenge, mice that were primed with antigen following bystander inflammation exhibited reduced total pulmonary cellularity (Fig. 2a) as well as reduced eosinophil (Fig. 2b) and neutrophil (Fig. 2c) infiltration compared to controls, demonstrating that the immune-suppressive effect of poly(I:C)-mediated inflammation can inhibit antigen-specific mucosal recall responses that are anatomically disparate. Similarly, challenge with OVA-expressing A20 lymphoma17 resulted in a modest, but significantly diminished tumor resistance in poly(I:C)-treated mice compared to controls (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2b). These observations show that qualitatively diverse endogenous antigen-specific immune responses are suppressed in vivo when priming occurs following non-specific bystander inflammation.

Figure 2. Immunization following non-specific bystander inflammation results in diminished antigen-specific recall response.

(a–c) Airway response of mice challenged with intranasal OVA following OVA immunization in the context of PBS or poly(I:C) treatment (indicated by “–“ or “+”). Total Pulmonary cell counts for (a) mononuclear cells (b) eosinophils, or (c) neutrophils. Each symbol represents a single mouse. Data are representative of two independent experiments, n ≥ 4. (d) Growth of OVA-bearing A20-tGO tumor following OVA immunization in the context of PBS or poly(I:C) treatment. Thin lines represent individual mice, thick lines represent cumulative mean tumor size. Data compiled from two independent experiments, n = 11. P -values by (a–c) Student’s two-tailed t-test, or (d) Two-way ANOVA, * P <0.05. ** P <0.001.

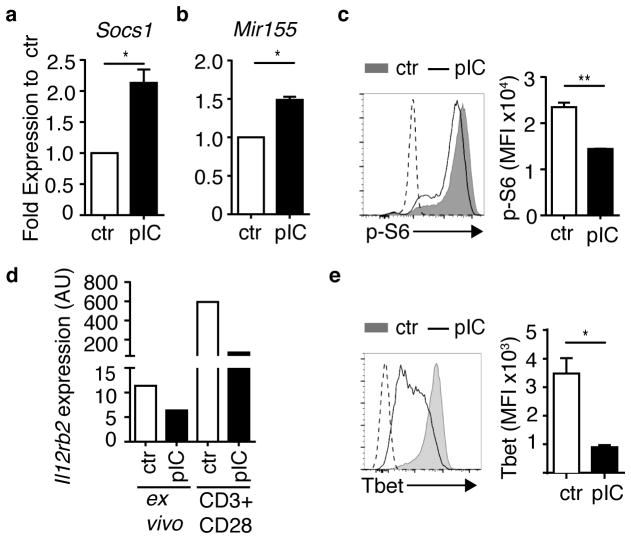

Inflammation alters molecular pathways in naïve CD4+ T cells

The marked impact of non-specific inflammation on antigen-specific responses and increase in Foxp3+ Treg cells, particularly at mucosal sites, suggested a potential impact of bystander inflammation on the priming of naïve T cells. To determine how non-specific bystander inflammation affects naïve CD4+ T cells, recombination-activated gene-deficient DO11.10 T cell antigen receptor (TCR)-transgenic mice (DO11.10 × Rag2−/−, hereafter referred to as DR) were treated with poly(I:C) and used as a source of naïve non-Treg CD4+ T cells stimulated with bystander inflammation in the absence of cognate antigen (Supplementary Fig. 3a) (hereafter referred to as inflammation-conditioned naïve T cells, or “ICTN”).

We first investigated the ex vivo expression of genes associated with regulation of T cell activation. Negative signal feedback molecules, such as SOCS1 and micro RNA 155 (MiR155), modulate effector T cell responses and support Treg cell stability and function18, 19. Expression of Socs1 mRNA and Mir155 RNA was elevated in directly isolated ex vivo ICTN DR CD4+ T cells compared to controls (Fig. 3a,b). Next, we examined mTOR signaling in antigen-stimulated CD4+ T cells by assessment of phosphorylated S6 riboprotein (p-S6) and p-AKT. As modulators of Teff vs. Treg cell differentiation, suppression of AKT-mTOR activation downstream of antigen receptor signaling pathways results in enhanced Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation20, 21. Upon antigen stimulation, phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 was reduced in ICTN DR cells (Fig. 3c). A modest, but consistent, reduction in AKT activation was also seen (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Additionally, after antigen stimulation, expression of genes that enable effector TH1 differentiation and repress Treg cell differentiation, Il12rb2 mRNA and T-bet protein22, 23, were substantially reduced in ICTN DR cells (Fig. 3d,e). These changes in cellular responsiveness occurred despite similar rates of proliferation and cell survival after antigen stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 3c,d). Together, these data suggest that non-specific bystander inflammation conditions naïve T cells into a refractory molecular “state” that could dampen T cell activation.

Figure 3. Naïve CD4+ T cells exposed to bystander inflammation exhibit altered molecular pathways that instruct T cell differentiation.

Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated from PBS (ctr)- or poly(I:C)-treated (pIC) DR mice as described in Supplementary Fig. 3a, and assessed (a,b) ex vivo, (c) after 16 h stimulation with antigen, (d) ex vivo or after 48 h stimulation with plate-bound CD3 plus CD28 without APCs as indicated, or (e) after 3 days stimulation with antigen. (a,b) Expression of (a) Socs1 mRNA and (b) Mir155 in ex vivo purified DR cells. Bar graphs depict expression in DR cells from pIC-treated mice relative to corresponding control DR cells (set to 1), normalized to (a) Rn18s and (b) Sno234 RNA. (c) DR cells were stimulated with OVA(323–339) peptide-pulsed APCs for 16 h, control cells were cultured with no antigen stimulation, depicted by dashed line. DR cells were stained for intracellular phospho-S6 (p-S6), representative flow cytometry histogram (left), mean florescence intensity (MFI) of p-S6 staining (right). (d) DR cells were purified and RNA was extracted from purified DR cells directly ex vivo, or after 48 h of stimulation with plate-bound anti-CD3 and CD28 (CD3+CD28) in vitro. Bar graphs depict Il12rb2 expression in DR cells from pIC-treated mice, normalized to Rn18s RNA. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (e) DR cells were stained for intracellular T-bet after 3 days of OVA peptide stimulation, representative flow cytometry histogram (left), mean florescence intensity (MFI) of T-bet staining (right). Dashed line on histogram indicates unstimulated control cells. (a–e) Data are representative of at least three independent experiments, n ≥ 3 mice per group. Bar graphs depict mean and SEM of triplicate values. P-values by student’s two-tailed t-test, *p<0.01, **p<0.001.

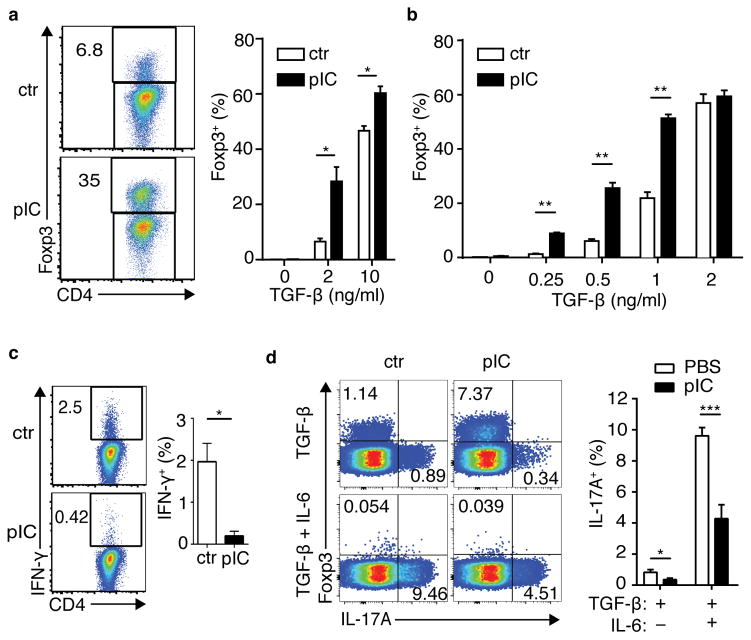

ICTN favor Treg cell and diminish Teff cell differentiation

The impact of bystander inflammation on molecular pathways following CD4+ T cell stimulation suggested that the de novo differentiation of effector and regulatory T cells may be impacted in response to antigen. Remarkably, when stimulated via TCR in the presence of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), the frequency of Foxp3+ cells was approximately 5-fold higher in ICTN DR as compared with control cells (Fig. 4a). This increase did not require the continued presence of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (Supplementary Fig. 4a), indicating that bystander inflammation imposed a cell-intrinsic physiological state upon the naïve T cells that resulted in enhanced de novo Treg cell generation after encounter with antigen. This effect was also seen with isolated naïve CD4+ T cells from poly(I:C)-treated wild-type BALB/c mice (Fig. 4b), indicating that this effect was not an artifact of a transgenic TCR. Notably, these effects were most prominent at sub-optimal TGF-β concentrations for Treg cell differentiation. Foxp3 promoter methylation was similar among naïve CD4+ T cells from ICTN and control DR mice, as well as BALB/c mice, indicating that this represented conversion of a “true” naïve CD4+ T cell population (Supplementary Fig. 4b). This data further suggests that the bystander inflammatory signals do not “prepare” the Foxp3 locus for responsiveness by altering DNA methylation.

Figure 4. Naïve CD4+ T cells exposed to bystander inflammation are conditioned for enhanced de novo Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation and reduced effector T-helper cell differentiation.

(a) Spleen and lymph node CD4+ T cells from control (ctr) or poly(I:C)-treated (pIC) DR mice were stimulated for 5 days with APCs pulsed with OVA peptide and TGFβ as shown, then assessed for intracellular Foxp3. Left panels, representative FACS plots; right panel, bar graph of frequencies of Foxp3+ DR cells. (b) Naïve CD4+ T cells from ctr or poly(I:C)-treated Balb/c mice were sorted and cultured with plate-bound anti-CD3+CD28 and TGFβ. Frequency of Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells is shown. (c) DR cells were cultured in non-skewing conditions, then stimulated with PMA+Ionomycin (P/I) and stained for intracellular IFNγ. (d) DR cells were cultured in the presence of TGFβ or TGFβ + IL6, then stimulated with P/I and assessed for intracellular Foxp3 and IL17A. Bar graphs depict mean plus SEM for triplicate values; representative data is shown for three to five independent experiments, n ≥ 3 mice per group. P-values by student’s two-tailed t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001.

Consistent with the patterns of molecular activation described above, ICTN DR cells produced less IFN-γ than control cells when cultured in non-skewing conditions (Fig. 4c). In TGF-β-supplemented cultures, low amounts of IL-17A production were seen, which was augmented by addition of IL-6 24. In both cases, ICTN DR cells produced significantly less IL-17A cytokine, even when Foxp3 expression was nearly completely abolished by addition of IL-6 (Fig. 4d). No changes were seen in expression of the TGF-β receptor, Tgfbr1, ex vivo, or activation of SMADs 2/3 with addition of exogenous TGF-β (Supplementary Fig. 4c,d), suggesting that molecular coordination serves to amplify the effect of existing TGF-β signaling components in ICTN cells. Together, these data show that naïve CD4+ T cells exposed to bystander inflammation prior to antigen encounter exhibit enhanced de novo Treg cell differentiation.

ICTN Treg cell differentiation follows viral infection and IFN-I

Poly(I:C) is commonly used as an adjuvant that mimics the effects of viral infection. To address whether enhanced Treg cell induction occurs in a setting of bystander activation during a viral infection, DR cells were transferred into BALB/c host, which were then infected with lymphocytic choriomeningititis virus (LCMV). At various times post-infection, CD4+ T cells from these mice were isolated and cultured with OVA peptide-pulsed APCs and TGF-β, similar to the approach used with poly(I:C) above. Induced Treg cell differentiation was significantly increased in DR cells from mice infected for seven days, as opposed to earlier or later timepoints (Fig. 5a and data not shown). While the timing of this effect differed between poly(I:C) treatment and LCMV infection, it is notable that the kinetics of innate inflammatory cytokine expression are such that enhanced Treg cell differentiation occurred in a timeframe closely following the peak of the in vivo inflammatory responses of each of these treatments25, 26. Notably, while poly(I:C) and the TLR7 ligand gardiquimod conditioned native T cells for enhance Treg cell induction, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) did not mediate this effect, suggesting a role for the qualitative nature of the inflammatory milieu in this response (Supplementary Fig. 5a).

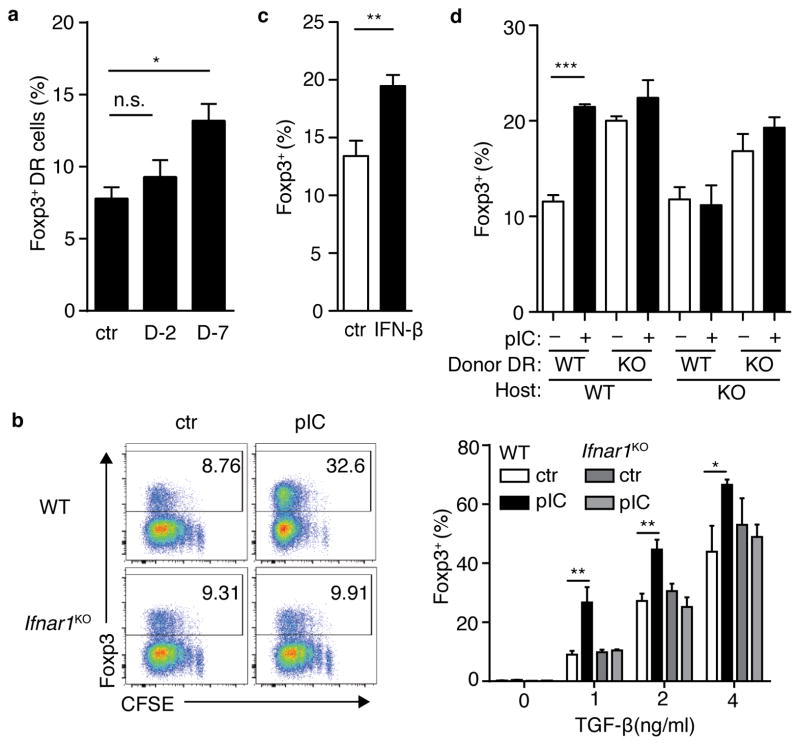

Figure 5. Antiviral bystander inflammation and type I interferon conditions naïve T cells for enhanced de novo Treg cell differentiation.

(a) DR cells were parked in BALB/c host mice, which were then inoculated with LCMV at seven days (D-7) or two days (D-2) prior to harvest; control mice (ctr) were left untreated. CD4+ T cells were isolated and cultured with OVA-pulsed APC and TGFβ for 5 days. Bar graphs indicate %Foxp3+ among cultured donor DR cells. (b) CD4+ T cells from control (ctr) and poly(I:C)-treated (pIC) wild-type (wt) and IFNaRKO mice were prepared as in Supplemental Fig.3a. After 5 days, cells were stained for Foxp3. Left panels, representative FACS plots; right, bar graph Foxp3+ DR frequencies. (c) DR splenocytes were incubated for 48 hours with PBS (ctr) or rIFN γ (IFN γ), then CD4+ T cells were purified and incubated with OVA-pulsed APC and TGF β. After 3 days, DR cells were assessed for Foxp3. (d) WT or IFNaRKO DR cells were transferred into WT or IFNaRKO Balb/c hosts, which were then treated with PBS (ctr) or poly(I:C) as indicated. Lymphocytes were cultured with Ova-pulsed APCs and TGF β for 5 days, then assessed for intracellular Foxp3. Bar graphs depict mean plus SEM of triplicate values, data are representative of two independent experiments, n ≥ 2 mice per group. P-values by student’s two-tailed t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Poly (I:C) and LCMV are known to specifically activate a substantial IFN-I response 27. Consistent with a role for IFN-I, incubation of splenocytes with poly(I:C) resulted in enhanced de novo Treg cell induction which could be blocked by neutralizing antibody against the receptor IFNAR1 (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Next, we assessed Treg cell induction in IFNAR1-deficient (Ifnar1KO) DR mice treated with poly(I:C). In contrast to wild-type DR cells, Ifnar1KO DR cells did not display enhanced Treg cell induction or diminished Teff cell differentiation after poly(I:C) treatment (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5c), demonstrating a clear dependence on IFN-I signals for this response. As shown above, ICTN DR cells expressed elevated Socs1 indicating expression of these feedback molecules as a consequence of IFNAR signaling. Consistent with the consequent upregulation of these negative feedback molecules, and despite similar Ifnar1 and Ifnar2 expression, ICTN DR cells exhibited diminished STAT1 activation after exposure to IFN-γ (Supplementary Fig. 5d,e). When naïve DR spleen cells were cultured in vitro with IFN-γ, subsequent de novo Treg cell induction was enhanced (Fig. 5c), indicating IFN-I alone is sufficient to elicit this response. A number of anti-inflammatory pathways are induced in response to IFN-I signals, including IL-10, PD-L1 and indolamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). Neutralization of IL-10 or PD-L1 by treatment with blocking antibodies did not abrogate the enhanced Foxp3 induction in ICTN cells (Supplementary Fig. 5f), nor did treatment with IDO inhibitor 1-methyltryptophan (1-MT) (Supplementary Fig. 5g). Furthermore, while we did observe expression of PD-L1 on ICTN, we were unable to detect expression of Foxa1 mRNA in these cells, which has been previously described as a mediator of IFN-I-regulated tolerance (data not shown)28.

To determine whether IFN-I plays a direct role on naïve CD4+ T cells to condition for enhanced Treg cell induction, wild-type or Ifnar1KO DR CD4+ T cells were transferred into wild-type or Ifnar1KO BALB/c host mice. These mice were treated with poly(I:C), and T cells were cultured with OVA-pulsed APCs and TGF-β. Using Ly6C as a surrogate marker for bystander inflammation among the donor DR cells29, wild-type DR cells were responsive to bystander inflammatory signals in both wild-type and Ifnar1KO host environments, while Ifnar1KO DR cells only showed mild activation in the wild-type host, and none in Ifnar1KO host (Supplementary Fig. 5h). Despite the apparent acquisition of some IFN-I-mediated bystander activating signals, enhanced Treg cell induction was only seen among wild-type DR cells in the wild-type host environment among ICTN versus controls (Fig. 5d), suggesting a role for IFN-I signaling in multiple cell types for coordination of this effect. In contrast, direct IFN-I signals seemed to be involved in the conditioning of naïve CD4+ T cells for diminished effector activity (Supplementary Fig. 5i). Interestingly, direct IFN-I signals seemed to inhibit de novo Treg cell differentiation basally, such that conditioning by bystander inflammation did not further enhance Foxp3 induction in Ifnar1KO DR cells.

Together, these data indicate that subsequent to bystander inflammation via IFN-I, naïve CD4+ T cells are refractory to further pro-inflammatory signals and are conditioned for enhanced Foxp3+ Treg cell induction. This effect may be due to a partially a cell-intrinsic homeostatic mechanism to limit basal Treg cell induction, perhaps as a mechanism to enable an IFN-I-mediated semi-“primed” state for immune responsiveness30. In the wake of inflammatory settings, APCs or stromal cells in the microenvironment that receive IFN-I signals enable an interaction that imparts a state of enhanced receptivity to Treg cell-inducing signals, such that a dynamic state of immune tolerance and increased frequency of Treg cell differentiation is revealed following bystander inflammation.

ICTN control of antigen-specific response is Foxp3-dependent

CD4+ T helper cells play a key role in promoting tumor immunity 31. However, immunosuppressive mechanisms employed by tumors can support the recruitment and induction of Treg cells that can suppress tumor-specific responses32, 33. To demonstrate the role of bystander inflammation directly on antigen-specific naïve CD4+ T cells in an anti-tumor response, enriched control or ICTN DR cells were transferred into BALB/c hosts, which were then immunized and challenged with OVA-expressing A20 lymphoma cells. BALB/c recipients of ICTN DR cells displayed more robust tumor growth than recipients of control DR (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 6a), indicating a direct role for antigen-specific CD4+ T cell suppression of the anti-tumor response. Importantly, this effect was reversed with Foxp3-deficient scurfy (sf) DR donors (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 6b), indicating that Foxp3 induction is critical for enhanced tumor tolerance by ICTN CD4+ T cells.

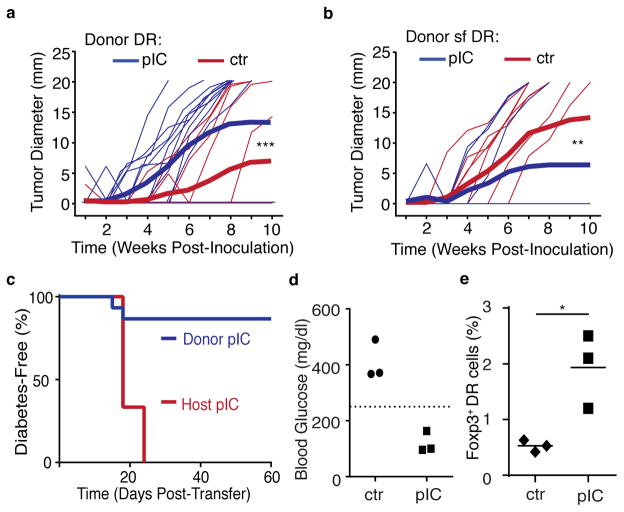

Figure 6. Bystander inflammation conditioning of naïve CD4+ T cells inhibits antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses in a Foxp3-dependent manner.

(a) CD4+ T cells from control (ctr) or poly(I:C)-treated (pIC) DR mice were transferred into Balb/c hosts. Mice were immunized with OVA peptide and 7–10 days later were inoculated subcutaneously with A20-tGO lymphoma cells, and tumor growth was monitored. Thin lines represent measurement from individual mice, thick lines represent cumulative mean tumor size. (b) As in part (a), but donor cells were Foxp3-mutant scurfy (sf) DR CD4+ T cells. (c) RIP-mOva/RAGKO host mice received ICTN DR cells and were left untreated (Donor pIC), or received ctr DR cells, and host mice were injected with pIC (Host pIC), and blood glucose was monitored. Graph shows diabetes-free survival. (d–e) Ctr or ICTN DR CD4 T cells were transferred into RIP-mOva/RAGKO host mice, all mice were treated with pIC, and donor DR cells were assessed 20 days later (summarized in Supplementary Fig. 6d). Each symbol represents a single mouse, data from one of two independent experiments shown, n=6. (d) Blood glucose levels at day 20, dashed line indicates the threshold for clinical diagnosis of diabetes. (e) Frequency of Foxp3+ donor DR cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes at day 20. Data compiled from (a) three independent experiments, n=14 or (b,c) two independent experiments, n=10. P-values by (a,b) Two-way ANOVA or (f) student’s two-tailed t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.0005, ***p<0.0001.

To better define the role of antigen-specific naïve CD4+ T cell response, we next turned to a model of autoimmune diabetes. In this model, the only T cells present in RIP-mOva × Rag2KO host are islet-specific donor DR CD4+ T cells, and induction of Treg cells from these donors is critical for islet tolerance8. Poly(I:C)-mediated bystander inflammation triggered islet autoimmunity and undermined Foxp3 induction in this setting when islet-specific control naïve CD4+ T cells encountered antigen (Fig. 6c, red line)8. In contrast, when DR cells were exposed to poly(I:C)-induced inflammation prior to antigen exposure to generate ICTN cells, untreated host RIP-mOva × Rag2KO mice displayed very low incidence of diabetes (Fig. 6c, blue line)8. When sf/DR were used as donors, all mice became diabetic regardless of treatment, underscoring the importance of Foxp3 for tolerance in this scenario (Supplementary Fig. 6c). To test the tolerogenic capacity of ICTN DR cells, control or ICTN DR cells were transferred into RIP-mOva × Rag2KO host mice, all of which were then treated with polyI:C (Supplementary Fig. 6d). In contrast to recipients of control cells, recipients of ICTN DR cells had normal blood glucose concentrations at day 20 post-transfer (Fig. 6d). Furthermore, Foxp3+ Treg cell frequencies were elevated among the ICTN donor DR cells compared to controls, demonstrating that this process of enhanced Treg cell induction following bystander inflammation can occur even in conditions that are highly unfavorable to Foxp3 induction (Fig.6e).

Timing of inflammation and antigen controls ICTN response

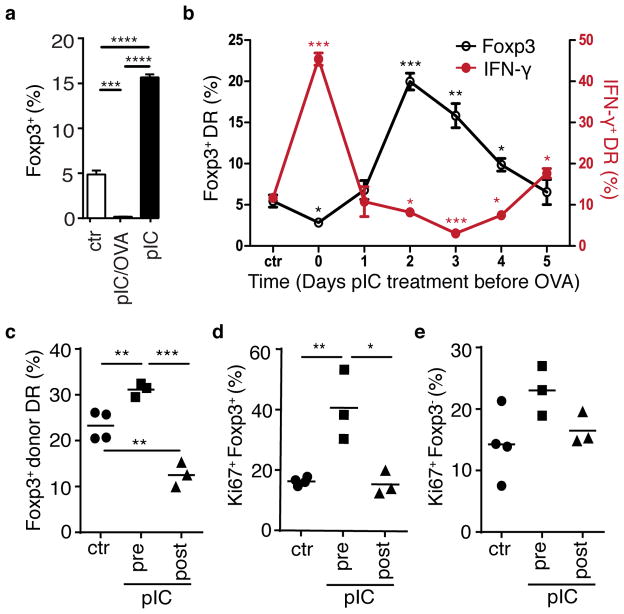

These findings implicate the timing of bystander inflammation relative to antigen encounter in the determination of Treg or Teff cell differentiation. Indeed, comparison of cultured DR cells from mice treated with poly(I:C) alone versus poly(I:C) plus OVA peptide demonstrated that Treg cell induction was diminished by concurrent signals, and enhanced by decoupled signals (Fig. 7a). To delineate the temporal role of bystander inflammation relative to antigen, DR cells were transferred into BALB/c host mice, which then received staggered injections of poly(I:C) prior to harvest of lymphocytes such that discrete waves of bystander inflammation were assessed at six different timepoints from five days prior through to lymphocyte harvest. Following this treatment regimen, lymphocytes were harvested and then cultured with OVA-pulsed APCs in the presence of TGF-β (see diagram of experimental setup, Supplementary Fig. 7a). Assessment of donor DR cells indicated that expression of surface molecules associated with antigen-independent bystander inflammation, PD-L1, CD69, and Ly6C were expressed in a transient manner (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Donor DR frequencies were consistent among all timepoints, indicating that these cells are not subject to significant attrition following bystander inflammation (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Importantly, assessment of intracellular Foxp3 and IFN-γ demonstrated markedly enhanced Teff cell differentiation when bystander inflammation and antigen were temporally coordinated (timepoint “0”), and Treg cell induction enhanced at a later “inflammation/antigen decoupled” time (timepoints “2–3”), and returning to levels similar to PBS-treated control at the furthest timepoints (Fig. 7b). This effect was confirmed in vivo using antigen-specific Treg cell induction via oral antigen delivery (Fig. 7c). Furthermore, proliferation of induced Treg cells, but not non-Foxp3+ cells, was enhanced when those cells had been exposed to bystander inflammation prior to antigen, further supporting a role for pre-exposure to inflammation in the increased numbers of induced Foxp3+ Treg cells upon cognate antigen recognition (Fig. 7d,e). Together these data demonstrate that non-specific bystander inflammation can differentially condition naïve CD4+ T cells to favor Teff cell or Treg cell differentiation, and this conditioning is linked to the relative timing of antigen and inflammatory signals.

Figure 7. Timing of bystander inflammation relative to antigen signal determines conditioning for regulatory versus effector cell differentiation.

(a) DR mice were treated with pbs (ctr), poly(I:C) alone (pIC), or poly(I:C) and OVA peptide (pIC/OVA) on two consecutive days, and on the third day CD4+ T cells were isolated and cultured with OVA-pulsed APC and TGF β for 3 days. Bar graph depicts % Foxp3+ DR. (b) DR cells were transferred into Balb/c host mice, which were then treated with poly(I:C) at indicated timepoints prior to harvest of spleen and lymph node cells and culture with OVA-pulsed APCs (summarized in Supplementary Fig. 7a). After 5 days, cells were stimulated with PMA+Ionomycin, and intracellular IFN γ (red line) and Foxp3 (black line) were assessed. (a,b) Mean plus SEM shown of triplicate values, data are representative of two independent experiments, n=2 mice per group. P-values as indicated relative to control. (c–e) DR cells were parked in BALB/c host mice, which were treated with pbs (ctr) or poly(I:C) either 2–3 days prior (pIC, pre) or 1–2 days after (pIC, post) addition of OVA protein in drinking water for 3 days. On day 7 after start of OVA feeding, mesenteric LN were harvested and donor DR cells were assessed for (c) frequency of Foxp3+ cells and donor DR expression of Ki67 proliferation antigen in (d) Foxp3+ DR cells and (e) Foxp3-negative DR cells. Each symbol represents data from an individual mouse, data are representative of two independent experiments, n ≥ 6. P-values by student’s two-tailed t-test, *p<0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001, ****p<0.00001.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to determine how non-specific bystander inflammation in the absence of cognate antigen stimuli impacted CD4+ T cell responses. Our results show that the process of bystander inflammation could inhibit the immune response to antigen by conditioning of naïve CD4+ T cells to be refractory to Teff cell differentiation and enhance Treg cell induction. The effect of such bystander conditioning could be modulated by the temporal relationship of the inflammation and antigen signals, such that coordinated signals undermined Treg cell induction, while temporally decoupled signals enhanced Treg cell induction. These results suggest a paradigm for T cell priming signals, and reveal an underlying principle for the apparent duality of the role of innate inflammation as both a driver and inhibitor of T cell responses12, 13.

The effects of bystander inflammation on subsequent T cell differentiation were greatest at suboptimal differentiation conditions. This characteristic would be consistent with the notion that the refractory state of naïve T cells following bystander inflammation acts as a temporary “buffer” to prevent unwanted autoimmune responses while still preserving the ability to adjust immune responses according to need. Notably, impaired anti-tumor immunity in the presence of ICTN DR cells was reversed when these cells did not express functional Foxp3. This would suggest that Foxp3 itself plays an important role as a component of a “master switch” molecular complex that guides Treg cell differentiation in ICTN CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, this supports the concept that pro-effector molecular factors are also mobilized in this process, and the end result for T cell differentiation depends upon the balance of these factors34. While our results did not directly demonstrate a Foxp3-dependent control switch for Teff vs. Treg cell induction in this context, lineage-tracing approaches support the notion that transient low-level de novo Foxp3 expression does occur in CD4+ T cells in inflammatory contexts35.

Bystander inflammation conditioning of naïve CD4+ T cells was dependent upon IFN-I, a critical component of TLR-mediated optimization of T cell responses36. Our adoptive transfer experiments suggest that IFN-I signals can play a direct role on both antigen-specific CD4+ T cells as well as other cells in the microenvironment to mediate both anti- and pro- Foxp3-inducing effects. While this is not as apparent in monoclonal DR/IFNARKO mice themselves, this effect was revealed in the context of the lymphoreplete environment, suggesting a role for other lymphocyte subsets (B cells, Treg cell, etc.) for this effect. Upon enhanced IFN-I signal during pIC-mediated bystander inflammation, IFN-I signal action on the surrounding cells in the microenvironment mediated a release of this basal inhibition of Foxp3, resulting in an apparent increase in frequency of de novo Treg cell induction among WT DR cells. IFN-I plays a complex role as an immunomodulatory cytokine, both as a promoter and inhibitor of antigen-specific immune responses37. In the clone 13 model of chronic LCMV infection, IFN-I receptor blockade can initiate CD4+ T cell-dependent viral clearance38, 39. Additionally, the immunosuppressive role of IFN-I in chronic LCMV has been linked to suppression of mechanisms of type I effector T cell differentiation40, 41. These studies have demonstrated a clearly reversible refractory state. Akin to this, we have demonstrated that the same bystander inflammatory response can both undermine as well as enhance Treg cell induction, depending upon its temporal relationship with antigen encounter. These lines of evidence suggest an intriguing possibility that quiescent naïve CD4+ T cells adjust the qualitative nature of their response to antigen in a dynamic manner that corresponds to temporal “windows” defined by environmental cues.

The physiological impact of the differentiation outcomes for ICTN CD4+ T cells has important ramifications for health and disease. The results presented here reveal a previously unappreciated dimension of CD4+ T cell biology, namely the ability of naïve T cells to modulate response to antigen by integration of signals over time. This type of molecular coordination likely evolved to mitigate potential for autoimmunity following cellular damage and release of self-antigens during infection. Indeed, epidemiological data supports the notion that environmental conditioning of the immune system by infection diminishes the aberrant immune responses that lead to autoimmunity42. The flip side of this immunoregulatory process is enhanced susceptibility to heterologous superinfection and immune escape of tumors. As the anti-parallel to autoimmunity, tumor immunity is similarly complicated by conflicting roles for the immunomodulatory role of inflammatory responses43, 44. The interplay of inflammatory processes acting in-trans on the homeostatic immune and tissue-supporting microenvironment may even play an important role in early progression of tumorigenesis45, 46. Conceivably, the process of tumorigenesis in the context of infectious- or tumor-derived inflammation could be enhanced by conditioning of newly infiltrating naïve T cells for de novo Treg cell induction during the process of immunoediting. Such an effect could partially account for the relentless growth and metastasis of tumors despite relatively high levels of immune cell infiltrate compared to similar healthy tissues.

Critical for an effective but non-harmful immune response by T cells is the integration of positive and negative feedback signaling over time. By providing signals to alter the quality of responses during the course of a response to infection, we propose that the inflammatory milieu produced by innate immune mechanisms coordinates effector and regulatory lymphocyte responses as a series of waves that promote both immunity and self-tolerance. As an evolutionary adaptation, this process is likely a component of the “metastable equilibrium” that enables sustainable levels of viral control without deleterious immunopathology during intractable chronic infection47. These concepts may be useful for lending nuance to vaccine and immunotherapeutic approaches to achieve more finely tuned outcomes.

Methods

Mice

BALB/cAnNCrl (BALB/c) and C57BL/6NCrl (B6) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. C.B6(Cg)-Rag2tm1.1Cgn/J (Recombination Activating Gene 2-deficient, Rag2KO), C.Cg-Tg(DO11.10)10Dlo/J (DO11.10) and B.Cg-Foxp3sf/J (scurfy) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Scurfy mice were backcrossed >11 generations to BALB/c background. Transgenic mice expressing membrane-bound OVA under control of the rat insulin promoter (RIPmOVA) mice on BALB/c background were provided by A. Abbas (UCSF, San Francisco, CA). Ifnar1KO mice on BALB/c background were provided by M. Orr (Infectious Disease Research Institute, Seattle, WA). Sex-matched male and female mice aged 8–12 weeks were used. No specific exclusion criteria were used in mouse experiments. Animals were housed in Specific Pathogen Free facilities and experiments were conducted in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Benaroya Research Institute.

Tumor studies

A20-tGO lymphoma cells expressing OVA were a generous gift from A. Marshak-Rothstein (University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA). Tumor cells were tested for murine pathogens, including Mycoplasma spp. prior to use (IMPACT pathogen test, IDEXX BioResearch). In vivo tumor studies using A20-tGO cells were conducted as described17. Briefly, tumor cells were expanded in vitro in complete RPMI with G418 (Invitrogen). Mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 1 × 106 live tumor cells in the flank. Tumor growth was assessed by direct measurement of the maximum diameter of palpable tumor mass. Mice with tumor diameter >15 mm were considered at experimental endpoint.

In vivo induction of bystander activation and immunizations

High-molecular weight poly(I:C) was purchased from Invivogen. For systemic in vivo responses, 100 μg of poly(I:C) was injected intraperitoneally for 2 consecutive days. Where indicated, 50 μg of OVA 323–339 peptide (Anaspec) was injected i.p. with poly(I:C) 14–18 h after the last injection, spleen and peripheral lymph nodes were harvested for cell preparations. For intranasal delivery of poly(I:C), mice were anesthetized with isoflourene and 25 μg of poly(I:C) was aspirated into the nostril via pipette. Immunization with whole OVA protein (Sigma) was via subcutaneous injection in Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant (IFA) (Sigma) emulsion, or orally via supplementation of drinking water (1% w/v) for four days. LCMV-Armstrong was generously provided by D. Campbell (Benaroya Research Institute, Seattle, WA). Mice were inoculated with 2 × 105 p.f.u. LCMV via intraperitoneal injection.

Induction of asthma

Recombinant murine Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin (TSLP) was a generous gift from Amgen. For short-term acute asthma induction (summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1g), mice were primed intranasally with OVA and TSLP using a modification of the protocol as previously described15. Briefly, mice were treated with 50μg poly(I:C) or PBS intranasally on days -2 and -1, then primed with OVA (25 μg) and TSLP (20 μg) on days 0 and 3, then challenged with intranasal OVA (25 μg) for two consecutive days starting on day 7–9. Two to three days after the first OVA challenge, mice were euthanized and single-cell suspensions of perfused lung tissue were assessed by flow cytometry. For airway inflammation memory T cell response (summarized in Supplemental Fig. 2a), mice were treated with 100μg poly(I:C) or PBS i.p. on days -3 and -2, then immunized subcutaneously with OVA (50 μg) emulsified in IFA on day 0, and 12–14 days later were challenged with one dose of OVA with TSLP as described above, followed by two consecutive doses of OVA only. Two days after the last challenge dose, mice were euthanized and perfused lung tissue was assessed as described. A minimum of 6 mice per group was used to achieve reasonable statistical power, n ≥ 3 per experiment.

Mouse diabetes model

Rag2KO DO11.10 mice (DR mice) with transgenic T cell receptor recognizing OVA epitope 232–339 in the context of I-Ad class II Major Histocompatibility Complex were used for donor T Cells. Purified CD4+ T cells from DR donor mice were transferred into RIP-mOVA/ Rag2KO (RO/RAGKO) host mice. Donor or host mice were treated as described in figure legends. Mice were evaluated for diabetes by blood glucose monitoring using Ascencia Contour glucometer system (Bayer AG). Mice were considered diabetic upon two consecutive daily blood glucose measurements exceeding 250 mg/dl.

Flow cytometry and sorting

Antibodies for cell surface staining for CD4 (RM4–5), D011.10 TCR (KJ1–26), CD25 (eBio3C7), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MEL-14), GITR (YGITR 765), Ly6G (1A8), Ly6C (HK1.4), CD45, B220, MHC Class II (M5/114.15.2), CD11b (M1/70), CD3 (2C11), Siglec-F (E50-2440) and CD11c (N418) were purchased from eBioscience, Biolegend or BD Biosciences. Unlabeled anti-CD3 (2C11) and anti-CD28 (PV-1) were purchased from the University of California San Francisco Antibody Core. Intracellular staining for Foxp3 (FJK-16s), T-bet (4B10), IFNγ (XMG1.2), IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1), IL-10 (JES5-16E3), Ki-67 (B56) (eBioscience, Biolegend or BD Biosciences) was conducted using eBioscience Foxp3 intracellular staining reagents according to manufacturer’s instructions. Intracellular staining for phospho-STAT1 (4a) (BD Biosciences), phospho-SMAD2/3 (D27F4), phospho-AKT (D9E) and phospho-S6 Ribosomal protein (D57.2.2E) (Cell Signaling Technology) was conducted as previously described48. Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated using no-touch magnetic bead purification (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec). Where indicated, cells were further sorted as described by florescent antibody labeling using FACSAria cell sorting system (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometric analysis utilized LSRII, Canto, and FACSCalibur cytometers (BD Biosciences), and data was analyzed with FlowJo Software.

In vitro cultures

For in vitro bystander activation, 3 μg/ml of poly(I:C) or 100 U/ml of recombinant IFN-γ (R&D Systems) was used. To block type I interferon signaling, 10 μg/ml anti-IFNAR1(MAR1-5A3, eBioscience) was used. To test in vitro Treg cell suppression, sorted CD25+ CD4+ T cells were mixed with CFSE-labeled naïve CD62Lhi, CD44lo CD25neg CD4+ T cells at indicated ratios. Naïve T cells with no Treg cells were used for controls. Sorted cells were mixed with irradiated RAGKO splenocytes and stimulated with 0.1 μg/ml plate-bound anti-CD3 (2C11) and assessed by flow cytometry two days later. CFSE dilution of non-Treg CD4+ T cells was used to calculate proliferation index of responding cells49 and activation of responding non-Treg CD4+ T cells was assessed by surface CD25 and intracellular T-bet. For in vitro T cell cultures, spleen and lymph nodes were processed to single-cell suspensions and naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated as described above. T cells were then mixed at a 1:3 or 1:4 ratio with irradiated splenocytes from naïve Rag2KO donors, and T cell receptor stimulation was achieved as indicated by either addition of OVA 323–339 peptide or plate-bound anti-CD3 (clone 2C11, UCSF Antibody Core). Various concentrations of recombinant hTGF-β (Peprotech) were added to cultures as indicated, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry 3 to 5 days later. Except as specified in figure legends, 1–2 ng/ml of TGF-β were used. For in vitro cultures, data shown as mean plus SEM for three technical replicates for each indicated condition representing a single mouse. n designations for independent experiments/mice as indicated. For intracellular cytokine analysis, day 5 cultures were re-stimulated with either plate-bound anti-CD3+CD28 (5 μg/ml and 1 μg/ml, respectively) or PMA and ionomycin in the presence of Golgi inhibitor (BD Pharmingen) for 5 h. Blocking antibodies anti-PDL1 (clone 10F.9G2, eBioscience), anti-IL10 (clone JES5-2A5, UCSF Antibody Core), and isotype control (rat IgG2a) were used at final concentration of 10 μg/ml final concentration in culture. 1-MT (Sigma) was reconstituted in NaOH and pH adjusted to 7 to make a stock concentration of 20 mM, and added to culture media at a final concentration of 100 μM50. Cultured cells were stained with live/dead cell stain (Fixable Viability Dye, eBioscience) prior to antibody staining. Cells were cultured in complete RPMI (Sigma) with 5% Fetal Bovine Serum (Sigma).

Analysis of gene expression

Cell pellets containing equivalent cell numbers were resuspended in Qiazol lysis buffer and RNA was isolated using miRNeasy total RNA isolation kit (Qiagen). Protocols for mRNA or miRNA sample preparation were followed as indicated by manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated with Primescript Reverse Transcriptase (Clontech) or Multiscribe reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). TaqMan probes (Life Technologies) were used for Socs1, Socs3, Mir155, Il12rb2 and Tbx21, with Rn18s and Sno234 for normalization controls for mRNA and miRNA, respectively. Other qPCR primer sequences for use with Syber Green reagents (Sigma) as follows were used: Ifnar1 F 5′-AGCCACGGAGAGTCAATGG-3′; Ifnar1 R 5′-GCTCTGACACGAAACTGTGTTTT-3′; Ifnar2 F CTTCGTGTTTGGTAGTGATGGT-3′; Ifnar2 R 5′-GGGGATGATTTCCAGCCGA-3′; Tgfbr1 F 5′-TCCAAACAGATGGCAGAGC-3′; Tgfbr1 R 5′-TCCATTGGCATACCAGCAT-3′. For normalization controls, primers for Gapdh F 5′-TCCATGACAACTTTGGCATTG-3′ and Gapdh R 5′-CAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGA-3′ were used. Samples were acquired on ABI 7500 RT-PCR system.

Foxp3 promoter methylation analysis

Cells were harvested as indicated in figure legends, and DNA isolation and bisulfite conversion using Epitect Plus DNA bisulfite conversion kit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Analysis of Foxp3 promoter sequence conversion was conducted as previously described51. Samples were obtained from 3 mice per group, and 8–10 sequences per sample were analyzed.

Statistics

Statistical analysis tests described in figure legends were calculated with Prism 5 (GraphPad) analysis software. Statistical tests used and estimates of variation within groups were based on previously published results using similar approaches as described here. Assumption of equal variance was applied to all statistical tests, except where stated in figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Campbell, J. Hamerman and E. Bettelli for helpful discussion and S. Ma and Aru K. for technical assistance. We thank A. Abbas, M. Orr, and A. Marshak-Rothstein for mice and materials. Supported in part by Postdoctoral Fellowship 121930-PF-12-071-01-LIB by the American Cancer Society and NIAID T32 AI007411 (L.J.T.), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Cooperative Center for Cellular Therapy, and NIH grant CA182783 (SFZ).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.J.T. and S.F.Z. developed the study. L.J.T. and J.F.L. designed and performed the experiments. A.C.V., T.D.T., and Z.L.U. performed in vitro experiments. L.J.T. and S.F.Z. wrote the manuscript, and all authors contributed to manuscript editing.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Information can be found in the online version of this paper.

References

- 1.Yoshimura A, Naka T, Kubo M. SOCS proteins, cytokine signalling and immune regulation. Nature reviews Immunology. 2007;7(6):454–465. doi: 10.1038/nri2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitz ML, Weber A, Roxlau T, Gaestel M, Kracht M. Signal integration, crosstalk mechanisms and networks in the function of inflammatory cytokines. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1813(12):2165–2175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott-Browne JP, Shafiani S, Tucker-Heard G, Ishida-Tsubota K, Fontenot JD, Rudensky AY, et al. Expansion and function of Foxp3-expressing T regulatory cells during tuberculosis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204(9):2159–2169. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haribhai D, Williams JB, Jia S, Nickerson D, Schmitt EG, Edwards B, et al. A requisite role for induced regulatory T cells in tolerance based on expanding antigen receptor diversity. Immunity. 2011;35(1):109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilate AM, Lafaille JJ. Induced CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in immune tolerance. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:733–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annual review of immunology. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Duin D, Medzhitov R, Shaw AC. Triggering TLR signaling in vaccination. Trends in Immunology. 2006;27(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson LJ, Valladao AC, Ziegler SF. Cutting edge: De novo induction of functional Foxp3+ regulatory CD4 T cells in response to tissue-restricted self antigen. Journal of immunology. 2011;186(8):4551–4555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srivastava S, Koch MA, Pepper M, Campbell DJ. Type I interferons directly inhibit regulatory T cells to allow optimal antiviral T cell responses during acute LCMV infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211(5):961–974. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffman RL, Sher A, Seder RA. Vaccine Adjuvants: Putting Innate Immunity to Work. Immunity. 2010;33(4):492–503. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyman O. Bystander activation of CD4+ T cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2010;40(4):936–939. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christen U, von Herrath MG. Do viral infections protect from or enhance type 1 diabetes and how can we tell the difference? Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8(3):193–198. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills KH. TLR-dependent T cell activation in autoimmunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11(12):807–822. doi: 10.1038/nri3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bach JF. Infections and autoimmune diseases. Journal of autoimmunity. 2005;25(Suppl):74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Headley MB, Zhou B, Shih WX, Aye T, Comeau MR, Ziegler SF. TSLP conditions the lung immune environment for the generation of pathogenic innate and antigen-specific adaptive immune responses. Journal of immunology. 2009;182(3):1641–1647. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durrant DM, Metzger DW. Emerging roles of T helper subsets in the pathogenesis of asthma. Immunological investigations. 2010;39(4–5):526–549. doi: 10.3109/08820131003615498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saff RR, Spanjaard ES, Hohlbaum AM, Marshak-Rothstein A. Activation-induced cell death limits effector function of CD4 tumor-specific T cells. Journal of immunology. 2004;172(11):6598–6606. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi R, Nishimoto S, Muto G, Sekiya T, Tamiya T, Kimura A, et al. SOCS1 is essential for regulatory T cell functions by preventing loss of Foxp3 expression as well as IFN-γ and IL-17A production. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208(10):2055–2067. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu LF, Thai TH, Calado DP, Chaudhry A, Kubo M, Tanaka K, et al. Foxp3-dependent microRNA155 confers competitive fitness to regulatory T cells by targeting SOCS1 protein. Immunity. 2009;30(1):80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haxhinasto S, Mathis D, Benoist C. The AKT–mTOR axis regulates de novo differentiation of CD4+Foxp3+ cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205(3):565–574. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delgoffe GM, Kole TP, Zheng Y, Zarek PE, Matthews KL, Xiao B, et al. The mTOR Kinase Differentially Regulates Effector and Regulatory T Cell Lineage Commitment. Immunity. 2009;30(6):832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamane H, Paul WE. Early signaling events that underlie fate decisions of naive CD4(+) T cells toward distinct T-helper cell subsets. Immunological reviews. 2013;252(1):12–23. doi: 10.1111/imr.12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei J, Duramad O, Perng OA, Reiner SL, Liu Y-J, Qin FX-F. Antagonistic nature of T helper 1/2 developmental programs in opposing peripheral induction of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(46):18169–18174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703642104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441(7090):235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Swiecki M, Cella M, Alber G, Schreiber RD, Gilfillan S, et al. Timing and magnitude of type I interferon responses by distinct sensors impact CD8 T cell exhaustion and chronic viral infection. Cell host & microbe. 2012;11(6):631–642. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barchet W, Cella M, Odermatt B, Asselin-Paturel C, Colonna M, Kalinke U. Virus-induced interferon alpha production by a dendritic cell subset in the absence of feedback signaling in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195(4):507–516. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsumoto M, Seya T. TLR3: interferon induction by double-stranded RNA including poly(I:C) Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2008;60(7):805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Carlsson R, Comabella M, Wang J, Kosicki M, Carrion B, et al. FoxA1 directs the lineage and immunosuppressive properties of a novel regulatory T cell population in EAE and MS. Nat Med. 2014;20(3):272–282. doi: 10.1038/nm.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dumont FJ, Coker LZ. Interferon-alpha/beta enhances the expression of Ly-6 antigens on T cells in vivo and in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16(7):735–740. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830160704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taniguchi T, Takaoka A. A weak signal for strong responses: interferon-alpha/beta revisited. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2001;2(5):378–386. doi: 10.1038/35073080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knutson KL, Disis ML. Tumor antigen-specific T helper cells in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2005;54(8):721–728. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou G, Drake CG, Levitsky HI. Amplification of tumor-specific regulatory T cells following therapeutic cancer vaccines. Blood. 2006;107(2):628–636. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou G, Levitsky HI. Natural regulatory T cells and de novo-induced regulatory T cells contribute independently to tumor-specific tolerance. Journal of immunology. 2007;178(4):2155–2162. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, Ivanov II, Min R, Victora GD, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453(7192):236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyao T, Floess S, Setoguchi R, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Waldmann H, et al. Plasticity of Foxp3(+) T cells reflects promiscuous Foxp3 expression in conventional T cells but not reprogramming of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2012;36(2):262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longhi MP, Trumpfheller C, Idoyaga J, Caskey M, Matos I, Kluger C, et al. Dendritic cells require a systemic type I interferon response to mature and induce CD4+ Th1 immunity with poly IC as adjuvant. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206(7):1589–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Navajas JM, Lee J, David M, Raz E. Immunomodulatory functions of type I interferons. Nature reviews Immunology. 2012;12(2):125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teijaro JR, Ng C, Lee AM, Sullivan BM, Sheehan KC, Welch M, et al. Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling. Science. 2013;340(6129):207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1235214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson EB, Yamada DH, Elsaesser H, Herskovitz J, Deng J, Cheng G, et al. Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science. 2013;340(6129):202–207. doi: 10.1126/science.1235208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stelekati E, Shin H, Doering TA, Dolfi DV, Ziegler CG, Beiting DP, et al. Bystander chronic infection negatively impacts development of CD8(+) T cell memory. Immunity. 2014;40(5):801–813. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osokine I, Snell LM, Cunningham CR, Yamada DH, Wilson EB, Elsaesser HJ, et al. Type I interferon suppresses de novo virus-specific CD4 Th1 immunity during an established persistent viral infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(20):7409–7414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401662111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bach JF. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;347(12):911–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nature reviews Immunology. 2006;6(11):836–848. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trinchieri G. Cancer and inflammation: an old intuition with rapidly evolving new concepts. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:677–706. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Conroy H, Marshall NA, Mills KH. TLR ligand suppression or enhancement of Treg cells? A double-edged sword in immunity to tumours. Oncogene. 2008;27(2):168–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Virgin HW, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Redefining chronic viral infection. Cell. 2009;138(1):30–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koch MA, Thomas KR, Perdue NR, Smigiel KS, Srivastava S, Campbell DJ. T-bet(+) Treg cells undergo abortive Th1 cell differentiation due to impaired expression of IL-12 receptor beta2. Immunity. 2012;37(3):501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyons AB. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. Journal of immunological methods. 2000;243(1–2):147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mellor AL, Baban B, Chandler PR, Manlapat A, Kahler DJ, Munn DH. Cutting Edge: CpG Oligonucleotides Induce Splenic CD19+ Dendritic Cells to Acquire Potent Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase-Dependent T Cell Regulatory Functions via IFN Type 1 Signaling. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(9):5601–5605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, et al. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS biology. 2007;5(2):e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.