Abstract

Background

In adolescence, internalizing (e.g., anxious, depressive, and withdrawn) and externalizing (e.g., aggressive, oppositional, delinquent, and hyper-active) symptoms are related with alcohol use. However, the directionality among internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, and alcohol use during adolescence is equivocal. Moreover, gender differences and similarities among these behaviors are not definitive in existing literature.

Objectives

This study examined longitudinal relationships between internalizing and externalizing symptoms and past-month alcohol use among adolescent boys and girls.

Methods

Using longitudinal survey data from a study of community-dwelling adolescents (n = 724), we estimated cross-lagged structural equation models to test relations between internalizing and externalizing symptoms (as measured by the Youth Self Report, YSR [Achenbach, 1991]) and self-report alcohol use in the past month among adolescents. Gender differences were tested in a multiple group structural equation model.

Results

Alcohol use at age 12 was a predictor of internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 15 for both boys and girls. With regard to gender differences, girls demonstrated an association between internalizing symptoms and drinking at age 12, whereas boys showed a stronger association between externalizing symptoms and drinking at age 18.

Conclusions/Importance

Early alcohol use is problematic for youth, and results of this study lend support to prevention programs for youth. Preventing or curbing early drinking may offset later externalizing and internalizing symptoms, as well as ongoing alcohol use, regardless of gender.

Keywords: alcohol, drinking, adolescence, gender, internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms

INTRODUCTION

Adolescents are more likely to use and abuse alcohol than other substances because alcohol is relatively easy to obtain (Johnston, O' Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2014). Approximately 24% (9.3 million) of U.S. adolescents between ages 12 and 20 reported that they had used alcohol in the past 30 days in 2012 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013). In 2012, 15.3% (5.9 million) adolescents reported binge drinking, and 4.3% (1.7 million) reported that they drink heavily (SAMHSA, 2013). A similar national study found that 22% of adolescents binge drink (Eaton et al., 2012). The overall percentage of current drinkers, binge drinkers, and heavy drinkers among adolescents has been gradually declining since 2002 (SAMHSA, 2013). Despite this positive trend, age at first drink among adolescents is getting younger (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Office of the Surgeon General, 2007), with 20.5% of youth experiencing their first drink before age 13 (Eaton et al., 2012). Alcohol use in adolescence has immediate and long-lasting adverse consequences, such as physical problems (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011), psychological distress (Brook, Brook, Zhang, Cohen, & Whiteman, 2002), poor academic performance, deviant or delinquent behaviors (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Miller, Levy, Spicer, & Taylor, 2006), other substance use (Boden & Fergusson, 2011; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014), risky sexual behaviors (Boden & Fergusson, 2011; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Stueve & O'Donnell, 2005), accidents (Boden & Fergusson, 2011), and alcohol use disorders later in life (Merline, O'Malley, Schulenberg, Bachman, & Johnston, 2004).

Gender Differences in Alcohol Use Among Youth

During adolescence, boys are more likely than girls to be classified as heavy drinkers (Chassin, Pitts, & Prost, 2002) although the gender gap in drinking is not as pronounced as in adulthood (Schulte, Ramo, & Brown, 2009). A recent analysis of the Monitoring the Future study found that girls (12.8%) had slightly higher rates of past-30 day alcohol use than boys (12.1%) in 8th grade (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014). However, Patrick and Schulenberg (2014) found that gender differences reversed in 12th grade, with 37.5% of girls and 42.1% of boys reporting that they had used alcohol in the past 30 days. The difference in rate for binge drinking was more marked, with 25.9% of 12th grade boys reporting that they had binged in the last 2 weeks, compared with 17.6% of girls (Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014).

The effects of early alcohol use on other risk behaviors may vary for girls and boys. In addition to alcohol disorders later in life, early drinking also predicted risky sexual behaviors in adolescent girls (Stueve & O'Donnell, 2005). Adolescent boys did not experience the same association between drinking and sexual behavior risks, which may reflect gender differences in social norms and expectations (Stueve & O'Donnell, 2005).

Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms and Drinking

A considerable body of literature has examined the directionality among internalizing and externalizing symptoms and alcohol use. Theorists posit that adolescents, particularly those with internalizing and externalizing symptomatology, may consume alcohol to offset negative feelings as a way of self-medication or tension reduction (Bukstein, Glancy, & Kaminer, 1992; Greeley & Oei, 1999; Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2003; Kloos, Weller, Chan, & Weller, 2009; Read & O'Connor, 2006).

Many studies have supported significant effects of externalizing symptoms on alcohol use. Externalizing symptomatology predicted increased risk of substance use (Costello, 2007; Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2008) such as early initiation of alcohol (King, Iacono, & McGue, 2004), regular alcohol use (Englund & Siebenbruner, 2012; King et al., 2004; Verdurmen, Monshouwer, Dorsselaer, Bogt, & Vollebergh, 2005), drunkenness (Niemelä et al., 2006), and excessive and heavy drinking in adolescence and early adulthood (Best, Manning, Gossop, Gross, & Strang, 2006; Englund, Ege-land, Oliva, & Collins, 2008; Kumpulainen, 2000). Additionally, a study using a cross-lagged model presented reciprocal effects between alcohol use and interpersonal aggression in late adolescence (Hicks & Zucker, 2014).

Empirical evidence has suggested a stronger effect of externalizing symptoms on alcohol use compared to internalizing symptoms. Research suggested that externalizing symptoms, but not internalizing symptoms, in adolescence were associated with a greater frequency of alcohol use in young adulthood (Steele, Forehand, Armistead, & Brody, 1995). A prospective longitudinal study using the Youth Self Report (YSR) measure revealed that externalizing symptoms were a significant predictor of alcohol use, whereas internalizing symptoms were not predictive of later alcohol use (Colder et al., 2013).

Overall, however, the findings of previous literature regarding the effects of internalizing symptoms on substance use are mixed. Some studies showed that childhood internalizing symptomatology increased the risk of substance use in adolescence and early adulthood (Caspi, Moffitt, Newman, & Silva, 1996; Hicks & Zucker, 2014; Hussong, Jones, Stein, Baucom, & Boeding, 2011a). However, others found that early internalizing symptoms predicted a lower level of weekly alcohol use (Maggs, Patrick, & Feinstein, 2008).

The effects of internalizing symptoms on alcohol use differ by subtypes of internalizing symptoms. For example, research has suggested that anxiety decreased the likelihood of excessive drinking (Best et al., 2006) and alcohol use disorders (Pardini, White, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2007), whereas depression increased excessive and heavy drinking (Best et al., 2006; Kumpulainen, 2000). King et al. (2004) found weak effects of internalizing symptoms, particularly depression, at age 11 on substance use at age 14.

It is well-documented that girls are more likely to exhibit internalizing symptoms (Axelson & Birmaher, 2001; Ghandour, Kogan, Blumberg, & Perry, 2010; Rohde, Beevers, Stice, & O'Neil, 2009), and boys are more likely to exhibit externalizing symptoms (Lead-beater, Kuperminc, Blatt, & Hertzog, 1999). However, gender differences regarding the effects of internalizing and externalizing symptoms on alcohol have not been clearly established. For instance, King et al. (2004) found that only boys showed an effect of externalizing symptoms on heavy drinking. Maggs, Patrick, and Feinstein (2008) found early internalizing symptoms predicted a decreased level of weekly alcohol use in adolescence among boys, but not girls. Verdurmen, Monshouwer, Dorsselaer, Bogt, and Vollebergh (2005) found no interactions between weekly alcohol use and gender as predictors of externalizing and internalizing problems. It is thereby possible that adolescents show gender differences in alcohol use if they have co-occurring problem behaviors. However, the literature on this subject is not definitive.

A smaller body of literature has suggested that substance use, including alcohol, predicted internalizing and externalizing symptoms, with some noted gender differences. Alcohol use may itself lead to the development of anxious or depressed mood among adolescents (Brook et al., 2002; Holahan et al., 2003). A study using a high-risk sample revealed long-term effects on internalizing symptoms of alcohol and drug use in adolescence (Trim, Meehan, King, & Chassin, 2007). In a primary care setting, adolescents with problematic substance use have shown an increased likelihood of experiencing a certain type of externalizing symptoms (i.e., conduct disorder) compared to those without such problems (Shrier, Harris, Kurland, & Knight, 2003). Girls with problematic substance use have demonstrated a higher risk of depression, but this relation was not found among boys (Shrier et al., 2003).

In summary, the current literature on alcohol and behaviors among adolescents is unclear regarding whether alcohol use predicts internalizing and externalizing symptoms or the reverse, particularly in general, non-clinical populations of youth. Whether both internalizing and externalizing symptoms are predictive of alcohol use is also equivocal. Furthermore, the role of gender and gender differences is of critical importance, given previous research findings.

In order to inform prevention and intervention strategies, this study aims to: (1) examine cross-lagged relationships among externalizing behaviors, internalizing symptoms, and the past-month alcohol use among adolescents; and (2) assess gender differences in relations between externalizing and internalizing symptoms and alcohol use during adolescence. Based on the literature, there are four specific hypotheses for this study: (1) externalizing and internalizing symptoms will be associated with past-month alcohol use among adolescents; (2) early alcohol use will predict later externalizing and internalizing symptoms; (3) early alcohol use (age 12) will predict later alcohol use (age 15 and 18); and (4) internalizing symptoms will be more closely related to alcohol use in girls than in boys, and externalizing behavior will be more closely related to alcohol use in boys than in girls.

METHOD

Data Source and Sample

Data for the current study were drawn from a community-based longitudinal cohort study, the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN; Earls et al., 2007), which investigated the effects of individual, family, school, and community factors on development and social behaviors of children and adolescents. The data were collected from youth and their primary caregivers in 1994–1997, 1997–1999, and 2000–2001 (Marz & Stamatel, 2005). Using a multistage stratified sampling approach, 80 neighborhood clusters were sampled, and then block groups were randomly selected from each neighborhood. Children and youth in seven age-cohort groups (i.e., ages 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18) and their primary caregivers were selected from 40,000 dwelling units in the 80 neighborhood clusters. Neighborhood clusters were stratified by socioeconomic and racial composition.

At Wave 1 the overall response rate was 75%. In the current study, the sample (n = 724) consisted of youth in cohort 12 who provided data at ages 12, 15, and 18 over the three waves of data collection. The sample was limited to youth who self-identified as White, Latino/Hispanic, or African American as only a small number of youth were members of other racial or ethnic groups. In the study sample, the percentage of respondents from Wave 1 who provided data at Wave 2 was 84.7% and at Wave 3 was 70.6%.

Measures

Behavioral Problems

The YSR, derived from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) developed by Achenbach (1991), is a measure of internalizing and externalizing symptoms of adolescents aged between 11 and 18. The YSR consists of 112 items scored with 3-point Likert scales (0 = not true, 1 somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very or often true). It assesses multiple domains such as=withdrawal, somatic complaints, anxious and depressed mood, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, delinquent behaviors, and aggressive behaviors.

Internalizing Symptoms

Internalizing symptoms were measured using the sub-scales of withdrawal, somatic complaints, anxious, and depressed mood in the YSR. In this study, 30 items which were identical across all three waves (7 items from withdrawn, 9 items from somatic complaints, and 14 items from anxious and depressed mood subscales) were included. Excluded items were missing from one or more waves of data collection (i.e., were not asked of all youth at all time points). The summed raw score from those items was used, generating a theoretical range of 0 to 60. Higher scores on the internalizing behaviors subscale indicate a greater degree of internalizing symptoms. In the current study, the internal consistency reliabilities of the internalizing subscale for youth ages 12, 15 and 18 were .87, .86, and .88, respectively.

Externalizing Symptoms

The externalizing symptoms in the YSR measure delinquent behaviors and aggressive behaviors (Achenbach, 1991). The externalizing symptoms included 19 items (9 items for delinquent behaviors and 10 items from aggressive behaviors) that were collected at all three waves. Again, items were excluded if they were not asked at each wave of data collection. Additionally, the item measuring use of Alcohol and Drugs was excluded, as alcohol use is expressly measured as a separate construct. The total, summed raw scores of the externalizing symptoms were used for data analysis (theoretical range 0–38). Higher scores reflect greater externalizing symptoms. The Cron-bach's alpha for the externalizing subscale ranged from .82 to .83 in the present study.

Alcohol Use

A single-item of alcohol use assessed the number of days respondents recalled having drunk alcohol in the past month, with six response options (0 = Never, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–5 days, 3 = 6–9 days, 4 = 10–14 days, 5 = 15–20 days, 6 = 21 days or more). For the purposes of analysis, these categories were reduced to the following: 0 = never drinking, 1 = drinking one or more days in the past month. Our rationale for choosing this dichotomous measure was twofold. Evidence suggested that measures of frequency are strong indicators of alcohol-related problems in youth, especially at ages 12 to 15 (Chung et al., 2012), and sparseness of endorsement at the higher levels (i.e., greater than 1–2 days in the past month) limited our ability to model relatively rare cases of frequent drinking among youth.

Demographics

Sociodemographic covariates included sex (0 = female, 1 = male), race/ethnicity of subjects, and salary and educational level of primary caregivers. Race/ethnicity was dummy coded into three categories: (1) Latino/Hispanic, (2) non-Hispanic Black, and (3) non-Hispanic White, with White used as the reference group. Salary, operationalized as annual household income, was categorized as follows: 1 = less than $5,000, 2 = between $5,000 and $9,999, 3 = between $10,000 and $19,999, 4 = between $20,000 and $29,999, 5 = between $30,000 and $39,999, 6 = between $40,000 and $49,999, and 7 = more than $50,000. Four original categories (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school graduate, 3 = some post-secondary education, 4 = Bachelor's degree or more) of educational level of primary caregivers in the PHDCN study were dummy coded (0 = less than high school level, 1 = high school graduation/GED or higher).

Data Analysis

First, descriptive analyses of model variables and covariates were conducted in SAS software version 9.3 to explore the characteristics of the data and to assess the distributions of variables to be included in models. Next, cross-lagged path models were estimated in Mplus version 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) to test the relations between alcohol use, internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms.

Cross-lagged path models have the ability to estimate reciprocal relationships with panel data by providing directionality and strength of the causal effects (Kline, 2011). They are designed to assess both the stability of a given construct over time (e.g., alcohol use) as measured through autoregressive paths (i.e., regressions of a given construct on the same construct measured at an earlier time) while simultaneously assessing cross-lagged associations between two constructs. This enables the investigator to assess the effect of a variable like alcohol use on externalizing behaviors at a given age (and vice versa) while controlling for the effects of earlier externalizing behaviors. This approach to assessing development minimizes the possibility that the association between two constructs can be explained by their earlier association (Laursen et al., 2012, p. 266).

Standard errors were adjusted for clustering by neighborhood using the survey modeling capabilities in Mplus (Asparouhov & Muthen, 2006). Model derived estimates controlled for sociodemographic covariates. In all models, fit was evaluated using a combination of absolute fit statistics (nonsignificant chi-square), residual based statistics (RMSEA and WRMR), and comparative fit statistics, including the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI: Tucker & Lewis, 1973) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI: Bentler, 1990). We evaluated model fit using current accepted cutoff values proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999).

For the initial models, a full model, including both girls and boys together was tested, and then a second order autoregressive model was added and estimated. The purpose of adding second order autoregressive paths was to adjust model estimates for upstream factors that may serve to confound cross-lagged relationships (e.g., the influence of age 12 drinking on age 18 drinking). On a practical level, model fit may improve as a result of accounting for the influence of second order effects.

Two multiple group models were estimated to test for invariance of model thresholds and intercepts of categorical and continuous outcomes using chi-square difference tests (Millsap & Yun-Tein, 2004). Finally, a multiple group model with invariant thresholds tested cross-lagged and autoregressive relationships between past-month alcohol use, internalizing and externalizing symptoms. In the multiple group model, all structural regression coefficients were allowed to vary but thresholds and intercepts were constrained across groups. We utilized Wald tests to explore whether gender differences were present in specific relationships between internalizing symptoms and alcohol as well as externalizing symptoms and alcohol.

Model parameters were derived using weighted least squares with mean and variance estimation (WLSMV: Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). In WLSMV, missing data were modeled using the expectation maximization algorithm based on the assumption of data being “missing at random” on exogenous covariates (Asparouhov & Muthén 2010). Indirect effects were computed using the delta method (Sobel, 1982).

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample and the responses for internalizing and externalizing symptoms and alcohol use at each time point. The results of bivariate analyses indicate that sociodemographic covariates did not differ significantly by gender. There were slightly more boys (51%) than girls in the sample. In both boys and girls, a large proportion of the sample identified as Latino/Hispanic or Black/African American, and the majority of primary caregivers reported an annual household income under $30,000. The percentage of youth endorsing past-month alcohol use increased at each wave of data collection in both girls and boys. Across all three ages, boys were more likely than girls to endorse drinking in the past month. Girls showed a higher level of internalizing symptoms at ages 12 (t = 2.27, p = .02), 15 (t = 4.77, p < .001), and 18 (t = 5.19, p < .001). Externalizing symptoms increased as=adolescents got older in both girls and boys, but no significant gender differences were found.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics by gender (n = 724)

| Male (n = 369) |

Female (n = 355) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | χ 2 | p | |

| COVARIATES | ||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Latino/Hispanic | 163 | 45.92 | 166 | 44.99 | .06 | .80 |

| Black/African American | 138 | 38.87 | 149 | 40.38 | .17 | .67 |

| White/Caucasian | 54 | 15.21 | 54 | 14.63 | .04 | .83 |

| High School Education | 192 | 54.08 | 203 | 55.01 | .06 | .80 |

| Caregiver's salary | 7.07 | .32 | ||||

| < $5,000 | 37 | 10.42 | 38 | 10.30 | ||

| 5,000–9,999 | 35 | 9.86 | 37 | 10.03 | ||

| 10,000–19,999 | 70 | 19.72 | 70 | 18.97 | ||

| 20,000–29,999 | 83 | 23.38 | 66 | 17.89 | ||

| 30,000–39,999 | 43 | 12.11 | 66 | 17.89 | ||

| 40,000–49,999 | 32 | 9.01 | 30 | 8.13 | ||

| >50,000 | 55 | 15.49 | 62 | 16.80 | ||

| CROSSLAG MODEL VARIABLES | ||||||

| Past-month alcohol use | ||||||

| Age 12 | 10 | 2.92 | 7 | 1.92 | .75 | .39 |

| Age 15 | 30 | 10.20 | 22 | 7.03 | 1.95 | .16 |

| Age 18 | 72 | 30.90 | 48 | 17.45 | 12.64 | <.001 |

| α | m | SD | m | SD | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing Subscale | |||||||

| Age 12 | .87 | 11.12 | 8.01 | 12.54 | 8.42 | 2.27 | .02 |

| Age 15 | .86 | 8.97 | 6.73 | 11.80 | 7.72 | 4.77 | <.001 |

| Age 18 | .88 | 9.05 | 6.57 | 12.48 | 7.45 | 5.19 | <.001 |

| Externalizing subscale | |||||||

| Age 12 | .82 | 7.08 | 5.23 | 7.13 | 5.46 | .14 | .89 |

| Age 15 | .82 | 8.91 | 5.39 | 8.56 | 5.46 | –.77 | .44 |

| Age 18 | .83 | 9.66 | 5.76 | 9.45 | 5.82 | –.39 | .69 |

Table 2 presents the fit indices of all models tested in this study. The chi-square test of model fit of the initial full model was significant (χ2(9) = 22.37, p = .008), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) value less than .95 also indicated poor model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Then, second-order autoregressive paths were added in the nested model, and the model fit indices improved. Specifically, the chi-square test of model fit was not significant (χ2(6) = 7.89, p = .246), and other model fit indices indicated excellent model fit (CFI = 1.00, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .021, WRMR = .23). The multiple group model showed the best results with respect to model fit indices. The chi-square test of model fit was not significant (χ2(12) = 12.10, p = .439), indicating an excellent model fit (Kline, 2011), and model fit indices also suggested excellent fit of the model to the data (CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = .005; WRMR = .29).

TABLE 2.

Model fit values

| χ 2 | df | p | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | WRMR | Δ χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full model | 22.37 | 9 | .008 | .87 | .98 | .045 | .41 | — | — |

| Second-order autoregressive | 7.89 | 6 | .246 | .97 | 1.00 | .021 | .23 | 16.82 | <.001 |

| Multiple group | 12.10 | 12 | .439 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .005 | .29 | — | — |

| Multiple group invariant | 16.41 | 21 | .746 | 1.04 | 1.00 | <.001 | .37 | 5.92 | .747 |

Note. *Single parameter constrained.

Table 3 presents the covariate estimates of youth alcohol use, internalizing and externalizing symptoms in the cross-lagged structural equation model. Significant covariate effects of higher level of annual household income (b = .24, p < .05) on alcohol use among boys were identified at age 15. Boys who had caregivers with more than a high school education showed a higher level of internalizing symptoms at age 18 (b = 2.55, p < .05). Among boys, Latino/Hispanic youth experienced higher externalizing symptoms than White youth at age 15. No significant covariate effects were found among girls.

TABLE 3.

Covariate estimates of alcohol use and anxious/depressed mood by gender (n = 724)

| Alcohol use |

Internalizing symptoms |

Externalizing symptoms |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 12 | Age 15 | Age 18 | Age 12 | Age 15 | Age 18 | Age 12 | Age 15 | Age 18 | |

| Female | |||||||||

| High school | –.26 | –.29 | –.10 | –.40 | –.97 | .26 | .01 | .59 | –1.24 |

| Latino/Hispanic† | –54 | –.23 | –.18 | 1.81 | 1.34 | –1.13 | –.58 | 2.72 | –.058 |

| Black† | .11 | –1.50 | –.85 | .80 | –.28 | –.39 | 1.27 | 1.04 | 2.80 |

| Salary | .14 | .001 | .11 | –.18 | .03 | .002 | –.05 | –.11 | .139 |

| Male | |||||||||

| High school | –.93 | –.22 | .65 | –1.21 | .19 | 2.55 * | –.14 | 1.35 | .16 |

| Latino/Hispanic† | –.66 | .54 | .38 | –.15 | 2.16 | –1.10 | –.17 | 2.22 * | –1.15 |

| Black† | –.68 | –.11 | .25 | .03 | 2.06 | –1.66 | .18 | 1.92 | –.54 |

| Salary | .05 | .24 * | .06 | –.20 | .07 | –.38 | –.17 | .10 | –.31 |

Note. The estimates are standardized

p < 05

Reference = White.

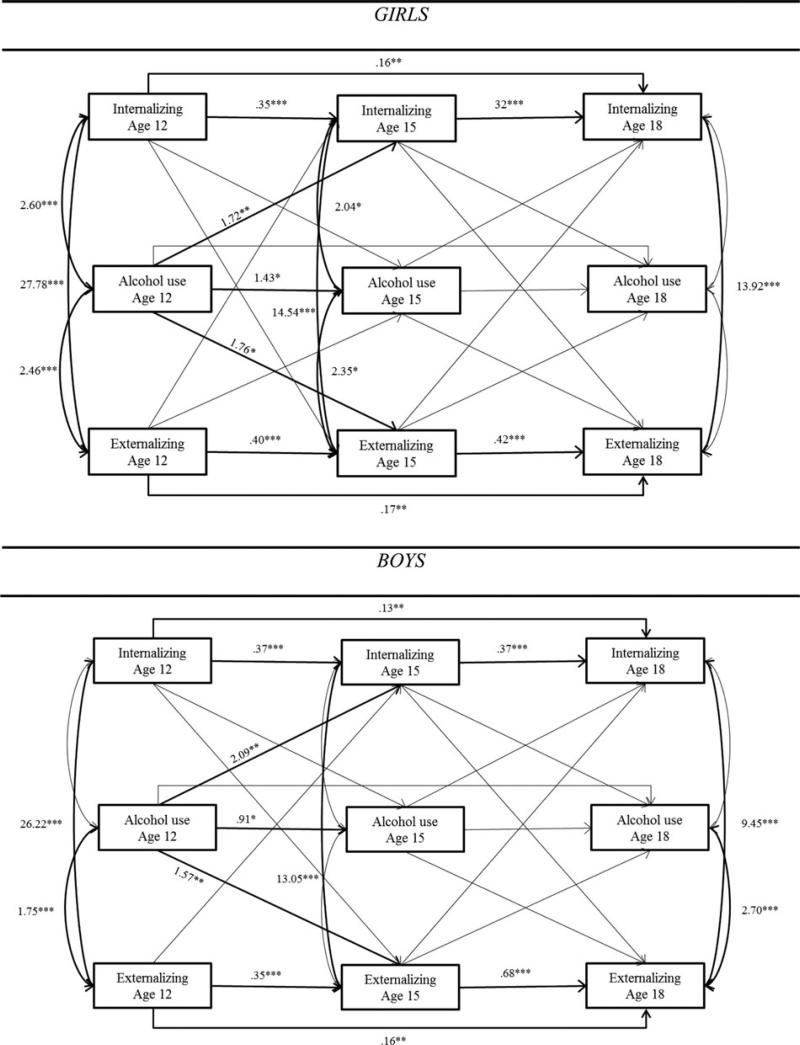

The results of the multiple group model are displayed in Figure 1. Significant cross-lagged relations between alcohol use and internalizing and externalizing symptoms were identified from age 12 to age 15 regardless of gender. Alcohol use at age 12 increased the probability of endorsing internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 15 for both boys and girls. However, alcohol use at age 18 was not predicted by alcohol use at ages 12 or 15. There was a significant association between internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms at each time point among boys (age 12: r = .629, age 15: r = .523, age 18: r = .398) and girls (age 12: r = .616, age 15: r = .492, age 18: r = .456). Additionally, alcohol use at age 12 was related to externalizing symptoms at age 12 for both boys (b = 1.75, p < .001) and girls (b = 2.46, p < .001).

FIGURE 1.

Cross-lagged model of internalizing and externalizing symptoms and alcohol use. Note. Covariate adjusted unstandardized coefficients; Dark line = statistical sig.; *p < 05, **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Indirect effects were present from alcohol use at age 12 through internalizing and externalizing behaviors at age 15 on both internalizing and externalizing behaviors at age 18. Among boys, alcohol use at age 12 had a specific indirect effect on internalizing symptoms at age 18 through internalizing symptoms at age 15 (b = .76; SE = .24; z = 3.12; p = .002). A similar effect was found for early alcohol use and externalizing symptoms at age 18 via age 15 externalizing symptoms (b = 1.72; SE = .48; z = 2.23; p = .026). This pattern was similar among girls with alcohol use at age 12 indirectly associated with internalizing symptoms at age 18 through age 15 externalizing symptoms (b = .56; SE = .21; z = 2.64; p = .008). An indirect effect of alcohol use of age 12 drinking on age 18 externalizing symptoms among girls was marginally significant (b = .74; SE = .42; z = 1.77; p = .077).

Some associations were gender-specific. Among girls, internalizing symptoms were significantly associated with past-month alcohol use at ages 12 (b = 2.60, p < .001) and 15 (b = 2.04, p < .05). Past-month alcohol use at age 15 was associated with externalizing symptoms at age 15 (b = 2.35, p < .05) among girls. In boys, alcohol use at age 18 was significantly associated with externalizing symptoms (b = 2.70, p < .001). The Wald test indicated significant gender differences between covariance of alcohol use and internalizing symptoms at age 12 as well as alcohol use and externalizing symptoms at age 18 (Table 4). This indicates that among girls, there was a significant association between alcohol use at age 12 and internalizing symptoms at age 12 that was not present in boys. Conversely, among boys, there was an association between alcohol use and externalizing symptoms at age 18 that was not present among girls.

TABLE 4.

Wald tests of parameter equality

| Parameter | Estimate | p |

|---|---|---|

| Covariance Parameters | ||

| Alcohol (age 12) ↔ Internalizing (age 12) | 6.14 | .01 |

| Alcohol (age 12) ↔ Externalizing (Age 12) | 1.47 | .23 |

| Internalizing (age 15) ↔ Alcohol (age 15) | 2.90 | .09 |

| Externalizing (age 15) ↔ Alcohol (age 15) | .99 | .32 |

| Internalizing (age 18) ↔ Alcohol (age 18) | 1.40 | .24 |

| Externalizing (age 18)↔ Alcohol (age 18) | 5.47 | .02 |

| Regression Parameters | ||

| Alcohol (age 12) → Internalizing (age 15) | .21 | .65 |

| Alcohol (age 12) → Externalizing (age 15) | 5.92 | .75 |

DISCUSSION

The findings of the present study paint a complex picture of gender differences and commonalities in the association of alcohol use with internalizing and externalizing symptoms. This sample is unique in its neighborhood-based sampling, ensuring geographic diversity in an urban area. Consistent with the urban setting for data collection, the individuals in this sample come primarily from lower-income households and are predominantly African American or Latino/Hispanic. In some ways, then, this is a higher-risk group than that captured in national probability samples, and the results of this study may offer specific insight into alcohol use and behavioral comorbidity in urban populations.

Study hypotheses are partially supported by the data. Externalizing behavior is associated with alcohol use at ages 12 and 15, and internalizing behavior is associated with alcohol use in girls at these ages. At age 18, externalizing behavior and alcohol use are associated in boys only. Alcohol use at age 12 does predict both internalizing and externalizing behavior at age 15 in boys and girls. However, alcohol use at age 15 is not significantly associated with either behavioral subscale score at age 18. Similarly, alcohol use at age 12 predicts alcohol use at age 15, but use at age 15 does not predict use at age 18. The gender differences support the hypothesis that alcohol use and internalizing behavior would be more related among girls (ages 12 and 15), and that alcohol use and externalizing behavior would be more strongly related in boys (age 18 only). These findings are discussed in more detail below.

Behavioral Effects of Early Alcohol Use

Our findings support a burgeoning literature focused on the detrimental effects of early alcohol use (Ellickson, Tucker, & Klein, 2003). Both boys and girls who report drinking at age 12 display higher levels of externalizing and internalizing symptoms at age 15. As one would expected, early alcohol use also predicts later use even after adjusting for internalizing and externalizing symptoms at age 12 and sociodemographic covariates. In both boys and girls, early alcohol use precedes behavioral problems and later drinking. It is surprising, however, that alcohol use at age 15 does not relate to use at age 18 in either boys or girls in the sample. This could reflect that alcohol initiation is more common in early adolescence than after age 14 (Guttmannova et al., 2011), or that by age 18 additional dynamics, such as peer pressure, are more influential than earlier alcohol use.

Broadly speaking, our findings are consistent with the literature with respect to the associations between externalizing behaviors and drinking (Bukstein et al., 1992; Greeley & Oei, 1999; Holahan et al., 2003; Kloos et al., 2009; Read & O'Connor, 2006), as these constructs are associated at age 12 in both genders and age 18 in boys in this sample. Nonetheless, the findings of this study differ from other literature exploring externalizing behaviors in that much of the literature has found that early externalizing or antisocial behavior predicts later alcohol use (Cho et al., 2014; Colder et al., 2013; Young, Sweeting, & West, 2008). There are a number of possible explanations for these differences. The present study is unique in modeling a separate pathway of internalizing behaviors at each time point. Research suggested that internalizing symptoms may not affect or could even reduce alcohol use behaviors (Colder et al., 2013; Steele et al., 1995), and internalizing symptoms are correlated with externalizing symptoms. Adjusting for internalizing symptoms in our models may therefore have attenuated the predictive value of externalizing symptoms.

Similarly, the current study benefits from measurement of all three constructs (externalizing, internalizing, and alcohol use) at three time points across adolescence. Models account for the stability of these constructs over time and measure their covariance (age 12) or residual covariance (age 15 and 18) at each time point. In our models, much of the variance in these constructs is explained by this stability over time and covariance. In other studies, models may not account for this shared variance over time leading to slightly different substantive conclusions about the predictive effect of externalizing or antisocial behaviors (e.g., Colder et al., 2013; Young et al., 2008).

PHDCN is a study of a specific urban locality in the United States. Relations between alcohol use and internalizing and externalizing behaviors may be very different from other studies of externalizing and internalizing behaviors with samples of youth in nonurban contexts (Colder et al., 2013) or in other countries (Cho et al., 2014). Myriad factors, including alcohol policies, alcohol availability, and social norms related to drinking among youth, may the course of alcohol use and externalizing/internalizing behaviors (Gilligan, Kuntsche, & Gmel, 2012; Paschall, Grube, Thomas, Cannon, & Treffers, 2012).

Developmental Stability of Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms and Drinking

In contrast to our unique findings on the role of early drinking, the findings of this study on the stability of these behaviors over time are in line with current literature. Both internalizing and externalizing symptoms earlier in adolescence predict later symptoms (Cho et al., 2014; Englund & Siebenbruner, 2012; Leadbeater et al., 1999). There is also a strong body of developmental research on pathways from early drinking in adolescence and later heavy drinking, and problems in later adolescence and adulthood (Cho et al., 2014; Englund et al., 2008; Huang, White, Kosterman, Catalano, & Hawkins, 2001; Zucker, 2008).

A preponderance of research has suggested that all three of the constructs (externalizing symptoms, internalizing symptoms, and alcohol use) are relatively stable over time in the general population of youth (Buist, Deković, Meeus, & van Aken, 2004) and co-occur during adolescence (Cosgrove et al., 2011). Our finding that internalizing and externalizing symptoms are associated with one another similarly in both genders is therefore in line with previous research (Englund & Siebenbruner, 2012). Evidence suggested that there is a robust relationship between externalizing symptoms and later substance use disorders (King et al., 2004; Steele et al., 1995), and scholars have posited that externalizing symptoms and substance use arise as a result of shared genetic risk factors (Iacono et al., 2008). The current models do not address upstream causal factors (e.g., symptoms in childhood before age 12), whereas our study reinforces the idea that alcohol use and externalizing symptoms develop stably in tandem across middle adolescence in both boys and girls.

Gender Differences in the Behavioral Correlates of Drinking

Most findings are consistent across gender, although we identified two gender differences in associations between alcohol use and externalizing and internalizing symptoms. There was a significant association between drinking and concurrent internalizing symptoms found in girls at age 12 that is not significant among boys. A significant association between drinking and externalizing symptoms is found among boys at age 18 but not for girls.

Other research studies conducted with girls have identified associations between alcohol use and increased internalizing pathology such as depressive symptoms (Dauber, Hogue, Paulson, & Leiferman, 2009). Hussong et al. (2011b) hypothesize that positive alcohol expectancies, coping motives for drinking, and interpersonal skills deficits underlie associations between internalizing symptoms and drinking in young adolescents. There is a body of research focused on internalizing pathways to substance abuse among youth (Hussong, Flora, Curran, Chassin, & Zucker, 2008; Hussong et al., 2011b; McCarty et al., 2012), but the role of gender differences in these processes is not fully understood. In the present study, internalizing symptoms and alcohol use covary at age 12, making it difficult to assert that internalizing symptoms are a precursor to use.

The finding suggesting a stronger association between externalizing symptoms and drinking frequency at age 18 among boys is consistent with the literature. This association may simply be a result of boys exhibiting higher levels of externalizing symptoms than girls (e.g., Leadbeater et al., 1999). Similarly, there may be gender specific associations between drinking and externalizing symptoms, in that current drinking is more likely among older boys but not among girls at the same age. Longitudinal research has identified an increasing growth rate of externalizing symptoms among males, but not females, from age 17 to age 24 (Hicks et al., 2007).

Limitations

The current study has a number of strengths including a unique community-based urban sample of youth surveyed longitudinally and a data analytic approach that measures differences in adolescent development by gender. Some methodological limitations need to be considered when interpreting study findings. All data in this study are self-report and therefore may be susceptible to social desirability or recall biases. The alcohol-related measure used in this study focuses on past-month drinking only, and does not address consumption levels (e.g., binge drinking) or alcohol problems. The YSR is a standardized measure of youth behavior, but not all items were included in all waves of data collection, so findings in the current study are not directly comparable to findings from other research. However, the internal consistency reliability of both internalizing and externalizing subscales remain acceptably high, despite exclusion of some items. Although the PHDCN data analyzed are a part of a highly rigorous survey of adolescent development among community-dwelling youth in Chicago, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations of youth in nonurban or rural areas or populations of youth in treatment.

Implications for Practice and Research

Despite the limitations, this study extends understanding regarding the developmental process, cross-lagged relationships, and gender effects among externalizing symptoms, internalizing symptoms, and alcohol use with the sample of adolescents. The current study supports ongoing efforts in early prevention and intervention for externalizing symptoms, internalizing symptoms, and alcohol use, which affects patterns of later behaviors. This study also reinforces the notion that early alcohol use is particularly problematic for youth, and provides greater evidence that preventing early alcohol use among youth may offset later externalizing and internalizing symptoms, regardless of gender. Our findings suggest that health care providers, school officials, and others in young adolescents’ lives need to screen for early alcohol use before adolescents develop a severe level of other problem behaviors. Early intervention for alcohol use in adolescence may help to decrease the risk of co-occurrence with other risky behaviors.

The findings of this study also indicate that gender-specific intervention may be beneficial in adolescence. In terms of alcohol use and externalizing symptom, boys in late adolescence may constitute a particularly at-risk population. Resources directed at resolving multiple behavior concerns in indicated youth, such as Multisystemic Therapy (Henggeler, Pickrel, & Brondino, 1999), could be appropriately targeted to older boys who display co-occurring externalizing and substance using behavior. Based on our findings, it may be effective to provide services to reduce problem alcohol use and to develop coping skills to deal with psychological symptoms in girls in early adolescence.

Early adolescence is potentially critical, not just for interrupting drinking but for potentially preventing other behavioral health symptoms. Universal prevention programs could begin even prior to this age, to interrupt the cascading risk between early drinking and later pathology. A recent systematic review of school-based alcohol prevention concluded that the Good Behaviour Game, Life Skills Training Program, and the Unplugged program may all have benefits (Foxcroft & Tsertsvadze, 2012).

Future research could further disentangle the complex relationships among internalizing and externalizing symptoms and alcohol use among adolescent boys and girls. For example, motivation to use alcohol, potentially bidirectional mechanisms (such as depression and alcohol use reinforcing one another), and changes in adolescent cognitive functioning related to both alcohol use and development were not explored in this study and could differ by gender.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This research was supported in part by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R03DA031264 (PI: Charlotte Bright).

GLOSSARY

- At-risk drinking

This is defined as drinking more than 14 standard drinks per week or 5 or more standard drinks on any day for men, and drinking more than 7 standard drinks per week or 4 or more standard drinks on any day for women (based on NIAAA drinking guidelines for the general population)

Biography

Hyun-Jin Jun, MSW, is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, School of Social Work in Baltimore, Maryland. Her primary research interests focus on risk behaviors including substance use and gambling among youth and emerging adults.

Hyun-Jin Jun, MSW, is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, School of Social Work in Baltimore, Maryland. Her primary research interests focus on risk behaviors including substance use and gambling among youth and emerging adults.

Paul Sacco, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland, School of Social Work in Baltimore, Maryland. His research focuses primarily on behavioral health and addictions with a focus on life course development.

Paul Sacco, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland, School of Social Work in Baltimore, Maryland. His research focuses primarily on behavioral health and addictions with a focus on life course development.

Charlotte Lyn Bright, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland, School of Social Work. Dr. Bright's research focuses on youth risk behavior and delinquency, with a particular focus on gender and service outcomes.

Charlotte Lyn Bright, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland, School of Social Work. Dr. Bright's research focuses on youth risk behavior and delinquency, with a particular focus on gender and service outcomes.

Elizabeth A. S. Camlin, MSW, is a graduate of University of Maryland, School of Social Work, where she worked as a research assistant.

Elizabeth A. S. Camlin, MSW, is a graduate of University of Maryland, School of Social Work, where she worked as a research assistant.

Footnotes

Color version of the figure in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/isum.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Comparison of estimation methods for complex survey data analysis. Mplus Web Notes; Los Angeles, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Axelson DA, Birmaher B. Relation between anxiety and depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Depression and anxiety. 2001;14(2):67–78. doi: 10.1002/da.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Manning V, Gossop M, Gross S, Strang J. Excessive drinking and other problem behaviours among 14–16 year old schoolchildren. Addiction Behaviors. 2006;31(8):1424–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Young people and alcohol: Impact, policy, prevention and treatment. Wiley-Blackwell; Chichester: 2011. The short and long term consequences of adolescent alcohol use. p. 32Á46. [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Archives of general psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist KL, Deković M, Meeus W, van Aken MAG. The reciprocal relationship between early adolescent attachment and internalizing and externalizing problem behaviour. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27(3):251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.012. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukstein OG, Glancy LJ, Kaminer Y. Patterns of affective comorbidity in a clinical population of dually diagnosed adolescent substance abusers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31(6):1041–1045. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of general psychiatry. 1996;53(11):1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;61(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S-B, Heron J, Aliev F, Salvatore JE, Lewis G, Macleod J, Dick DM. Directional relationships between alcohol use and antisocial behavior across adolescence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(7):2024–2033. doi: 10.1111/acer.12446. doi: 10.1111/acer.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Smith GT, Donovan JE, Windle M, Faden VB, Chen CM, Martin CS. Drinking frequency as a brief screen for adolescent alcohol problems. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):205–212. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1828. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Scalco M, Trucco EM, Read JP, Lengua LJ, Wieczorek WF, Hawk LW., Jr Prospective associations of internalizing and externalizing problems and their co-occurrence with early adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(4):667–677. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9701-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove VE, Rhee SH, Gelhorn HL, Boeldt D, Corley RC, Ehringer MA, Hewitt JK. Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(1):109–123. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ. Psychiatric predictors of adolescent and young adult drug use and abuse: What have we learned? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S97–S99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauber S, Hogue A, Paulson JF, Leiferman JA. Typologies of alcohol use in White and African American adolescent girls. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44(8):1121–1141. doi: 10.1080/10826080802494727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Chyen D. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 4. Vol. 61. Surveillance Summaries; Washington, DC: 2012. Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2011. pp. 1–162. 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Ten-year prospective study of public health problems associated with early drinking. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5):949–955. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Egeland B, Oliva EM, Collins WA. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: A longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction. 2008;103(s1):23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Siebenbruner J. Developmental pathways linking externalizing symptoms, internalizing symptoms, and academic competence to adolescent substance use. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35(5):1123–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxcroft DR, Tsertsvadze A. Cochrane review: Universal school-based prevention programs for alcohol misuse in young people. Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal. 2012;7(2):450–575. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour RM, Kogan MD, Blumberg SJ, Perry DF. Prevalence and correlates of internalizing mental health symptoms among CSHCN. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):e269–e277. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C, Kuntsche E, Gmel G. Adolescent drinking patterns across countries: Associations with alcohol policies. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2012;47(6):732–737. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags083. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeley J, Oei T. Alcohol and tension reduction. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 1999;2:14–53. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmannova K, Bailey JA, Hill KG, Lee JO, Hawkins JD, Woods ML, Catalano RF. Sensitive periods for adolescent alcohol use initiation: Predicting the lifetime occurrence and chronicity of alcohol problems in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(2):221. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Pickrel SG, Brondino MJ. Multisystemic treatment of substance-abusing and-dependent delinquents: Outcomes, treatment fidelity, and transportability. Mental Health Services Research. 1999;1(3):171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022373813261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Kramer MD, Krueger RF, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG, McGue M. Gender differences and developmental change in externalizing disorders from late adolescence to early adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(3):433–447. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.433. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.116.3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Zucker RA. Alcoholism: A life span perspective on etiology and course Handbook of developmental psychopathology. Springer; 2014. pp. 583–599. [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope and alcohol use and abuse in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(1):159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, White HR, Kosterman I, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Developmental associations between alcohol and interpersonal aggression during adolescence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38(1):64–83. doi: 10.1177/0022427801038001004. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Flora DB, Curran PJ, Chassin LA, Zucker RA. Defining risk heterogeneity for internalizing symptoms among children of alcoholic parents. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(01):165–193. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, Baucom DH, Boeding S. An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011a;25(3):390. doi: 10.1037/a0024519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, Baucom DH, Boeding S. An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011b;25(3):390–404. doi: 10.1037/a0024519. doi: 10.1037/a0024519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: Common and specific influences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O' Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on drug use: 1975-2013: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kloos A, Weller RA, Chan R, Weller EB. Gender differences in adolescent substance abuse. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2009;11(2):120–126. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen K. Psychiatric symptoms and deviance in early adolescence predict heavy alcohol use 3 years later. Addiction. 2000;95(12):1847–1857. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9512184713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Little TD, Card NA, editors. Handbook of developmental research methods. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Kuperminc GP, Blatt SJ, Hertzog C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(5):1268. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1268. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Patrick ME, Feinstein L. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol use and problems in adolescence and adulthood in the National Child Development Study. Addiction. 2008;103(s1):7–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Wymbs BT, King KM, Mason WA, Vander Stoep A, McCauley E, Baer J. Developmental consistency in associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol use in early adolescence. Journal Studies on Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73(3):444–453. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline AC, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: Prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(1):96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Levy DT, Spicer RS, Taylor DM. Societal costs of underage drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67(4):519. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millsap RE, Yun-Tein J. Assessing factorial invariance in ordered-categorical measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39(3):479–515. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus users guide. 7th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Niemelä S, Sourander A, Poikolainen K, Helenius H, Sillanmäki L, Parkkola K, Moilanen I. Childhood predictors of drunkenness in late adolescence among males: A 10-year population-based follow-up study. Addiction. 2006;101(4):512–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General . The Surgeon General's call to action to prevent and reduce underage drinking. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, White HR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Early adolescent psychopathology as a predictor of alcohol use disorders by young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S38–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Thomas S, Cannon C, Treffers R. Relationships between local enforcement, alcohol availability, drinking norms, and adolescent alcohol use in 50 California cities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(4):657. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Prevalence and predictors of adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking in the United States. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2014;35(2):193. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v35.2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, O'Connor RM. High-and low-dose expectancies as mediators of personality dimensions and alcohol involvement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67(2):204. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Beevers CG, Stice E, O'Neil K. Major and minor depression in female adolescents: Onset, course, symptom presentation, and demographic associations. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(12):1339–1349. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte MT, Ramo D, Brown SA. Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(6):535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrier LA, Harris SK, Kurland M, Knight JR. Substance use problems and associated psychiatric symptoms among adolescents in primary care. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6):e699–e705. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.6.e699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology. 1982;13:290–312. doi: 10.2307/270723. [Google Scholar]

- Steele RG, Forehand R, Armistead L, Brody G. Predicting alcohol and drug use in early adulthood: The role of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in early adolescence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65(3):380–388. doi: 10.1037/h0079694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A, O'Donnell LN. Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(5):887. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2012 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. 2013 NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No (SMA), 12-4713. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables/NationalFindings/NSDUHresults2012.htm. [PubMed]

- Trim RS, Meehan BT, King KM, Chassin L. The relation between adolescent substance use and young adult internalizing symptoms: Findings from a high-risk longitudinal sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(1):97. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Verdurmen J, Monshouwer K, Dorsselaer SV, Bogt TT, Vollebergh W. Alcohol use and mental health in adolescents: Interactions with age and gender—findings from the Dutch 2001 Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Survey. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2005;66(5):605. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R, Sweeting H, West P. A longitudinal study of alcohol use and antisocial behaviour in young people. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2008;43(2):204–214. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Anticipating problem alcohol use developmentally from childhood into middle adulthood: What have we learned? Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl1):100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]