Abstract

Introduction:

Relapse prevention (RP) remains a major challenge to smoking cessation. Previous research found that a set of self-help RP booklets significantly reduced smoking relapse. This study tested the effectiveness of RP booklets when added to the existing services of a telephone quitline.

Methods:

Quitline callers (N = 3458) were enrolled after their 2-week quitline follow-up call and randomized to one of three interventions: (1) Usual Care: standard intervention provided by the quitline, including brief counseling and nicotine replacement therapy; (2) Repeated Mailings (RM): eight Forever Free RP booklets sent to participants over 12 months; and (3) Massed Mailings: all eight Forever Free RP booklets sent upon enrollment. Follow-ups were conducted at 6-month intervals, through 24 months. The primary outcome measure was 7-day-point-prevalence-abstinence.

Results:

Overall abstinence rates were 61.0% at baseline, and 41.9%, 42.7%, 44.0%, and 45.9% at the 6-, 12-, 18- and 24-month follow-ups, respectively. Although RM produced higher abstinence rates, the differences did not reach significance for the full sample. Post-hoc analyses of at-risk subgroups revealed that among participants with high nicotine dependence (n = 1593), the addition of RM materials increased the abstinence rate at 12 months (42.2% vs. 35.2%; OR = 1.38; 95% CI = 1.03% to 1.85%; P = .031) and 24 months (45% vs. 38.8%; OR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.01% to 1.73%; P = .046).

Conclusions:

Sending self-help RP materials to all quitline callers appears to provide little benefit to deterring relapse. However, selectively sending RP booklets to callers explicitly seeking assistance for RP and those identified as highly dependent on nicotine might still prove to be worthwhile.

Introduction

Long-term smoking cessation is related to decreased mortality and morbidity,1–3 yet most smokers who achieve short-term abstinence eventually relapse to smoking. Among self-quitting smokers, the relapse rate may be as high as 95%.4 Among smokers receiving cessation treatment, 70% relapse.5 Even among smokers who successfully abstain for one full year, 10% eventually return to regular smoking.6 Consequently, effective interventions aimed at relapse prevention (RP) are essential for long-term cessation and decrease in smoking-related illness.

Cognitive behavioral counseling combined with pharmacotherapy is the most effective evidence-based approach to smoking cessation.5 Counseling interventions usually include and emphasize RP. However, very few smokers use counseling, often citing inconvenience.7 Therefore, the public health impact of this approach has been limited by poor population reach. On the other hand, telephone quitlines are effective5,8 and offer convenience as well as high cost-effectiveness relative to most other interventions for smoking cessation.9–13 Quitlines currently exist in all US states and throughout the world, reaching a large proportion of smokers annually.14 However, as with other cessation interventions, the rate of smoking relapse among quitline users remains high.15–19

A recent meta-analysis found that self-help approaches (ie, minimal interventions such as written materials) were the only empirically-supported interventions for preventing smoking relapse.20 One such self-help intervention was found to be efficacious and cost-effective among recently quit smokers.21–23 This intervention comprises a series of booklets, called Forever Free, with content that draws on empirical and theoretical research in RP.24–25 A quasi-experimental study previously found that these booklets also reduced relapse among callers to a state tobacco quitline, but only among those who had not received pharmacotherapy.26 Additionally, a modified version of the booklets was found to reduce postpartum smoking relapse among lower income women.27

The Forever Free intervention offers potential for further enhancing public health impact by adding a low-cost relapse-prevention component to existing telephone quitlines. The goal of the current study was to test the real-world effectiveness of adding the relapse-prevention booklets to the services of an existing state quitline. Based upon our previous research,21–22 we hypothesized that the Forever Free booklets would improve the long-term abstinence rates among adult smokers calling a telephone quitline. Although the booklets were originally developed to be distributed over 12 months,21 they were subsequently found to be equally efficacious and more cost-effective among self-quitters when delivered all at once.22 Hence, the two different distribution schedules were tested in the current clinical trial, with no specific hypothesis regarding their relative effectiveness for quitline callers.

Methods

Design Overview

A randomized three-arm equal allocation design was used to test the effectiveness of the Forever Free booklets among state quitline callers. The three conditions included: (1) Usual care (UC), comprised of the standard interventions provided by the New York State Smokers’ Quitline (NYSSQL); (2) Repeated Mailings (RM), which included UC, plus the eight Forever Free booklets sent to participants over a 12-month period; and (3) Massed Mailings (MM), which included UC, plus the eight Forever Free booklets sent to participants all at once. Assessments occurred at 6-month intervals, through 24 months.

Participants

Participants were clients of the NYSSQL. The inclusion criteria were (1) smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day over the month prior to calling the quitline; (2) at least 18 years old; (3) able to speak and read English; and (4) reached by the NYSSQL at their 2-week call back (see Procedures). Because quitline callers were offered smoking cessation medication, exclusion criteria included pregnancy or breastfeeding, heart attack or stroke within the past 2 weeks, current use of bupropion or varenicline, and serious cardiovascular problems (unless approved by their physician). There was no racial or gender bias in the selection of participants. Although the intervention was initially developed for individuals who had already achieved short-term abstinence, the intent of this effectiveness trial was to facilitate dissemination by minimizing burden to the quitline operators. Therefore, tobacco abstinence was not an inclusion criterion.

Procedures

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of South Florida and Roswell Park Cancer Institute. When smokers called the NYSSQL, an initial interview included collection of basic demographic information, smoking history, and eligibility screening for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Eligible smokers were then mailed 2 weeks of NRT. Approximately 2 weeks (10–14 days) following initial contact, quitline specialists called clients back to verify that they had received the NRT, provide any additional assistance, and inform eligible clients about the opportunity to participate in the relapse-prevention clinical trial. Clients were invited to “participate in a study to develop better ways to provide educational materials about quitting smoking.” Approximately 50%–70% of eligible NYSSQL clients were randomly selected and invited into the study per month until the required sample size was reached. Participants were recruited between October 2009 and April 2010.

Upon providing verbal approval, participants were randomized (without stratification or blocking) to 1 of 3 treatment conditions and contact information was acquired. Random allocation sequence was generated by NYSSQL research team using a pseudo-random number generator algorithm using a seed value of number of seconds from midnight at the time of the call. The quitline specialists inviting clients to participate in the study were not aware of the treatment assignment. All assessments (baseline and follow-up) and intervention materials were sent to participants via US mail. The treatment implementation and research roles were separated by site: the NYSSQL team sent all intervention materials at appropriate time points, and the Moffitt Cancer Center research team sent and received all of the assessment questionnaires. Receipt of the completed baseline questionnaire constituted consent for participation and enrollment into the study. Follow-up assessments were conducted via mail at 6-month intervals through 24 months. Participants were paid $20 for completing each assessment questionnaire, with a bonus payment of $50 if they completed all five assessments.

Intervention Conditions

Usual Care Condition

This condition comprised the standard intervention provided to current smokers who called the NYSSQL. It included the initial contact call and coaching interview, provision of a 2-week starter kit of NRT (client had a choice of nicotine transdermal patch, nicotine gum, or nicotine lozenge), and a 2-week proactive follow-up coaching telephone call. A “Ready to Quit” kit was mailed to current smokers after the initial call and included a congratulatory cover letter, a “Break Loose” stop smoking guide, a medications chart, and two single-page fact sheets about dealing with nicotine withdrawal and maintaining abstinence.

Repeated Mailing Condition

This condition comprised UC, plus eight Forever Free relapse-prevention booklets delivered as originally developed.21 The first booklet was mailed after participants were enrolled into the study, and the rest were mailed at the following time points: 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 12 months. The first booklet, “An Overview,” provides a general overview about quitting smoking, and each of the remaining seven booklets include more extensive information on topics related to maintaining abstinence: Smoking Urges; Smoking and Weight; What if You Have a Cigarette?; Your Health; Smoking, Stress, and Mood; Lifestyle Balance; and Life without Cigarettes. The content of the booklets is based on cognitive-behavioral theory24,28 and draws upon principles that typically represent the key relapse-prevention counseling interactions that occur in the clinical setting. They are written at the fifth to sixth grade reading level to maximize their accessibility to a wide range of individuals.29 The printing cost of the eight booklets was $5.58 per person.

Massed Mailing Condition

This condition comprised UC, plus the identical eight booklets as in the RM condition, but all of the booklets were sent to participants in a bundle upon study enrollment.

Measures

Baseline Measures

Demographic and smoking-related characteristics were assessed. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence,30 a standard, validated 6-item questionnaire, assessed tobacco dependence. Motivation to stop smoking was assessed via the Contemplation Ladder31 and the Stages of Change algorithm.32 The Abstinence-Related Motivational Engagement scale,33 a 16-item questionnaire, was used to measure post-cessation commitment to remaining smoke-free as evidenced by level of involvement in the quitting and maintenance process. Participant evaluation of the quitline services was assessed using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ).34 The items were rated on a scale of 1–4, with a total score range of 7–28. A five-point item was used to measure confidence in being smoke-free in 6 months. Finally, current and past use of smoking cessation interventions and cessation aids were assessed.

Follow-up Measures

At each follow-up, tobacco, and any use of pharmacotherapy or other smoking cessation assistance since the previous contact were assessed. Motivation to quit smoking, including the Contemplation Ladder, the Stages of Change algorithm, the Abstinence-Related Motivational Engagement, the CSQ, and the one-item measure of confidence to be smoke-free in 6 months were assessed. Eight CSQ-based items assessed participants’ evaluation of the Forever Free booklets. The CSQ items were rated on a scale of 1–4, with a total score range of 8–32. Participants in the two Forever Free treatment conditions reported at 12, 18, and 24 months which of the eight booklets they received. The primary outcome measure was 7-day point-prevalence abstinence.

Sample Size

Sample size was selected to detect minimum differences of 5% in the primary outcome measure (abstinence rates between pairs of conditions) using generalized estimating equation analyses. A priori sample size calculation indicated that at least 1133 smokers per condition would provide 80% power to detect differences under conservative assumptions about both the possible range of abstinence rates of UC condition and rates of attrition over the course of the study.

Statistical Analyses

Data analyses occurred in 2013–2014. Baseline demographic and smoking characteristics were compared across treatment conditions using one-way analyses of variance and chi-square tests, depending on the characteristics of the variable being tested. Satisfaction with quitline services at baseline and satisfaction with treatment at 6- and 12-month follow-ups was compared across the treatment conditions using analyses of variance. The primary hypotheses (Forever Free conditions vs. UC) were assessed using generalized estimating equations with an autoregressive working correlation structure. In the base model, treatment, time, and their interaction were used to predict 7-day point-prevalence across the four follow-ups. Potential moderators were tested individually by adding the moderator and associated interaction terms to the base model.

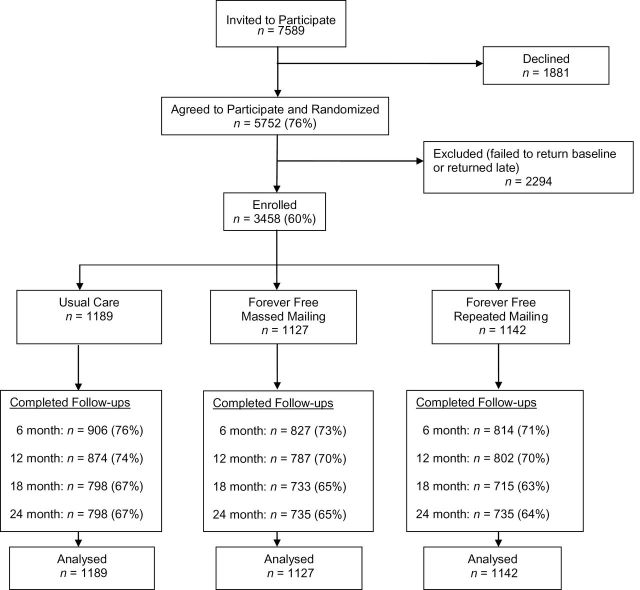

We used multiple imputation to handle missing data, which occurred primarily because of follow-up surveys not being returned at each of the four follow-up time-points (Figure 1). Our imputation approach used a Markov Chain Monte Carlo method35 which is based upon a missing at random assumption. Twenty imputed data sets were generated via PROC MI procedure in SAS software (SAS, version 9.3). The procedure incorporated 16 variables and 12 interaction terms: (1) smoking status at baseline and the four follow-ups, (2) the predictors for the models being tested (ie, treatment condition plus seven demographic and four smoking-related variables to be assessed as moderators), and (3) 12 computed variables representing the interaction of a moderator variable with treatment. Binary smoking status at each follow-up was finalized using adaptive rounding.36

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Results

Recruitment and Baseline Demographics

The CONSORT flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. Of the 7589 NYSQL clients invited to participate in the study, 5752 (76%) provided preliminary verbal consent and were randomized to treatment conditions. Of those randomized, 3458 (60%) returned the baseline questionnaire indicating consent and were enrolled in the study. Follow-up return rates did not differ statistically between groups.

Participant characteristics at baseline are presented in Table 1. Comparisons of the UC group with each of the two Forever Free groups revealed two significant differences. There was a higher percentage of males in the RM group (56.6%) compared to UC group (51.7%), X 2(1) = 5.50, P = .019. In addition, participants in the MM group reported a higher average cigarettes per day (20.3) compared to those in the UC group (19.2), t(2306) = 2.95, P = .009. Controlling for these differences did not affect the primary cessation outcome results.

Table 1.

Demographic and Smoking Variables at Baseline by Intervention Condition

| Usual care (n = 1189) | Massed mailing (n = 1127) | Repeated mailing (n = 1142) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||

| Sex (%): male | 51.7* | 54.3 | 56.6* |

| Age: M (SD) | 44.0 (13.5) | 43.8 (13.9) | 44.0 (13.4) |

| Race (%):white/Caucasian | 79.4 | 78.4 | 79.4 |

| Black/African American | 10.6 | 10.2 | 10.1 |

| Other | 7.9 | 9.4 | 8.1 |

| Refused to answer | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| Hispanic ethnicity (%) | 7.1 | 8.9 | 9.7 |

| Education (%):less than HS diploma | 8.7 | 12.3 | 11.1 |

| HS diploma or GED | 35.9 | 35.4 | 35.3 |

| College or technical school | 54.2 | 50.3 | 52.7 |

| Refused to answer | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Insured (%) | 74.6 | 76.3 | 74.5 |

| Married/living together (%) | 42.6 | 43.2 | 40.9 |

| Household income (median category) | $20–$30 000 | $20–$30 000 | $20–$30 000 |

| Smoking-related variables | |||

| Cigarettes per day: M (SD) | 19.2 (8.8)** | 20.3 (9.3)** | 19.8 (8.9) |

| FTND: M (SD) | 5.1 (2.2) | 5.2 (2.3) | 5.2 (2.2) |

| Years smoked: M (SD) | 22.3 (12.9) | 22.9 (13.1) | 22.5 (12.4) |

| Previous quit attempt: % | 39.6 | 37.7 | 38.2 |

| Live with smoker(s): % | 36.9 | 38.7 | 37.5 |

| Contemplation Ladder (0–11): M (SD) | 9.9 (1.7) | 9.8 (1.8) | 9.8 (1.8) |

| SOC—action: % | 54.2 | 53.1 | 54.6 |

FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; GED = general equivalency diploma; HS = high school; SOC = Stages of Change.

*P < .05; **P < .01 between treatment groups.

Survey Return Rates

Follow-up survey return rates decreased over time (Figure 1): 51.9% returned all four follow-ups, with no group differences, and 15.6% returned none of the follow-ups, with a lower percentage of those in the UC group (13.0%) than in the MM (16.0%) and the RM (17.8%) groups (Ps < .05). Compared to those who returned at least one follow-up survey, participants who did not return any follow-up surveys were more likely to be abstinent at baseline, female, a racial and/or ethnic minority, married, uninsured, and younger (Ps < .01).

Treatment Satisfaction

On average, participants were highly satisfied with the services they received from the NYSSQL. The overall mean score on the CSQ at baseline was 25.47 (SD = 2.85). There were no differences between the three treatment groups on satisfaction with NYSSQL services. Similarly, participants in the two Forever Free treatment conditions reported high levels of satisfaction with the intervention booklets. The overall mean score on the CSQ at the 6-month follow-up was 25.76 (SD = 4.61). At 12 months, the time by which the RM group participants have received all of the intervention booklets, the overall mean score on the CSQ was 26.09 (SD = 4.69). There were no differences between the MM and RM groups on satisfaction with the Forever Free intervention materials at either time-point.

Cessation Outcomes

Table 2 presents abstinence rates for each condition at each time point. The 7-day point-prevalence abstinence rate for the entire sample at baseline was 61%. The overall abstinence rates were 41.9%, 42.7%, 44%, and 45.9% at the 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-month follow-ups, respectively. The RM intervention consistently produced somewhat higher abstinence rates than the UC and MM interventions. However, generalized estimating equation analyses comparing either MM or RM against UC did not find significant group differences or group × time interactions. Analyses of smoking status at follow-up among the subset of participants (n = 2108) who had achieved abstinence by the baseline assessment (the true target of RP) also failed to reveal significant group differences in outcomes, with similar patterns of abstinence rates across conditions, but higher rates of abstinence overall. For example, at 24 months, the abstinence rates were 57.2%, 55.5%, and 61.7% for the UC, MM, and RM conditions, respectively.

Table 2.

Abstinence Rates (%) at Baseline and Follow-ups by Intervention Condition

| Usual care (n = 1189) | Massed mailing (n = 1127) | Repeated mailing (n = 1142) | Full sample (N = 3458) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 60.6 | 60.7 | 61.6 | 61.0 |

| 6 months | 41.3 | 40.2 | 44.1 | 41.9 |

| 12 months | 41.9 | 41.2 | 45.1 | 42.7 |

| 18 months | 43.9 | 43.0 | 45.1 | 44.0 |

| 24 months | 45.4 | 44.3 | 48.0 | 45.9 |

No statistically significant group differences or interactions were found; results based on multiple imputation (20 data sets).

None of the demographic or smoking-related variables presented in Table 1 were found to be significant moderators of the treatment effect. Post-hoc analyses were performed to compare the RM and UC participants based on “at-risk” subgroups, including low income, low education, racial and/or ethnic minority, and nicotine dependence. For each of the “at-risk” groups, the demographic and smoking-related variables were assessed and no significant group differences emerged. Therefore, analyses of treatment effects were conducted without any covariates. Logistic regression was used to assess abstinence rates at the 12-month follow-up (corresponding to the end of treatment in the RM condition), and the 24-month follow-up (corresponding to 12 month post treatment in the RM condition). As can be seen in Table 3, for those with relatively high nicotine dependence (Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence > 5; n = 1593), the RM condition showed higher abstinence rates than the UC condition at two critical time points. At 12 months, the abstinence rates were 42.2% versus 35.2% (OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.03% to 1.85%, P = .031). At 24 months, the abstinence rates were 45.0% versus 38.8% (OR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.01% to 1.73%, P = .046).

Table 3.

Abstinence Rates (%) at Baseline and Follow-ups by Intervention for Smokers With High Nicotine Dependence

| Usual care (n = 528) | Massed mailing (n = 536) | Repeated mailing (n = 529) | All (n = 1593) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 56.4 | 57.9 | 59.7 | 58.0 |

| 6 months | 36.4 | 38.5 | 42.0 | 39.0 |

| 12 months | 35.2* | 37.3 | 42.2* | 38.2 |

| 18 months | 37.0 | 40.4 | 43.1 | 40.2 |

| 24 months | 38.8* | 41.3 | 45.0* | 41.7 |

*P < .05 between intervention groups; results based on multiple imputation (20 data sets).

Lastly, in an effort to evaluate treatment integrity, participants in both of the Forever Free treatment groups were asked whether they received and read the intervention materials. With regard to receipt of intervention, among responders at the 12-, 18-, and 24-month follow-ups, 12.5% of the MM group and 8.0% of the RM group did not endorse receipt of a single booklet. Those who reportedly did not receive the intervention tended to have lower abstinence rates by 6.6%–8.1% across follow-up points than those who reported receiving the booklets, although the differences did not reach significance (Ps = .071–.161). With regard to whether participants read the booklets, 90% of responders reported having read the intervention booklets. At the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, abstinence rates were 42.8% and 43.70%, respectively, among those who reportedly read the booklets, compared with 27% and 29% among those who did not read the booklets (Ps < .03). The differences between those who read and those who did not read the booklets dropped to approximately 5% at the 18- and 24-month follow-ups, and were no longer significant (Ps > .28). Finally, we compared smoking status for the participants in the RM group who reported having read the booklets to those in the UC group. Similar to the primary outcomes, abstinence rates were greater for the RM group, but the difference did not reach significance at any of the follow-ups (all Ps > .17).

Discussion

This randomized controlled trial tested the real-world effectiveness of adding eight self-help relapse-prevention booklets to the standard services provided to smokers calling a state telephone quitline. We found that the Forever Free booklets failed to produce significantly higher abstinence rates than usual care at any follow-up point over 24 months. However, post-hoc analyses revealed that among individuals who reported high nicotine dependence at baseline, the provision of the Forever Free booklets distributed over a 12-month period produced higher quit rates relative to the standard quitline services at 12 and 24 months. Booklets delivered all at once did not produce higher abstinence rates than usual care. This contrasts with an earlier study of self-quitters, which found equivalent outcomes for the two distribution schedules.22 It may be that the booklets provide little additional benefit when they follow so closely in time a multicomponent quitline intervention, whereas a longer distribution schedule offers high-risk participants the benefits of both reminders of important concepts as well as maintained contact over time.

The findings from this study are in contrast to two earlier randomized controlled trials that did observe a benefit of providing the Forever Free booklets to smokers.21–22 However, both these earlier trials were based on unassisted recent quitters who proactively sought assistance for relapse-prevention. By contrast, the participants in the current study were smokers seeking assistance to stop smoking who were provided the Forever Free booklets as an adjunct to the Quitline service, which already included the provision of free NRT and counseling support. The conflicting findings between studies suggests the possibility that the Forever Free booklets, may be useful to subgroups of smokers who might contact a Quitline, such as those explicitly seeking assistance for RP, and perhaps heavily addicted smokers. However, it appears that sending self-help relapse-prevention materials to all Quitline callers adds little benefit to deterring relapse, and is therefore not recommended. This interpretation is consistent with a previous finding in which the Forever Free booklets reduced relapse only among quitline callers who did not receive pharmacotherapy.26 In the current study, all quitline callers received NRT, and hence, it was not possible to test or replicate the previous finding with non-NRT users.

When added to existing interventions, minimal self-help interventions, particularly those delivered across an extended time-frame, may have their greatest impact upon subgroups of smokers at greater risk, such as those with high nicotine dependence or those receiving substandard treatment (ie, self-quitters or quitline callers who do not receive NRT). This conclusion is also consistent with a recent finding that a similar self-help intervention for pregnant women was effective only for those in low-income households, perhaps due to lower access to services, resources, and optimal treatments.27 It is important to note, however, that the current intervention effect among highly dependent smokers was a post-hoc finding for which chance cannot be ruled out. Future effectiveness research is needed to replicate the booklets’ impact among highly nicotine dependent smokers.

Another reason for lack of a treatment effect may be the high abstinence rate (45.4%) achieved by the UC condition. To date, the best telephone quitline outcomes in the literature have been found with multiple counseling calls, with reported abstinence rates of up to 27%,18,37,38 although one study found little benefit beyond two counseling calls.15 The high 24-month abstinence rate in the UC condition may reflect selection bias. That is, participants who were available for the 2-week quitline call, agreed to participate in the study, and returned their baseline questionnaire may have had greater motivation to quit smoking. Another possibility is that, although each assessment was relatively brief by design, the regularly scheduled multiple assessments may have enhanced the perception of social support, which has been found to improve cessation outcomes.39 The multiple assessments may have also produced a “Hawthorne” or trial effect,40 resulting in higher than expected quit rates. The multiple contacts combined with provision of NRT and brief telephone counseling may have left little room for additional improvement by a minimal self-help intervention.

In an effort to explore another potential reason for the lack of outcome differences, we evaluated treatment integrity and found that between 8%–12% of participants claimed to have not received the Forever Free booklets. Although this finding did not impact the overall treatment outcomes, it highlights the inherent challenges that may be encountered in real-world effectiveness studies in which the researchers do not have direct control of intervention delivery. On the other hand, 90% of participants who reported receiving the booklets said that they read them. The high treatment compliance is consistent with high levels of satisfaction with the Forever Free intervention reported by participants in the current study. However, similar to results regarding receipt of booklets, having read the booklets did not impact the overall treatment outcomes.

This study has several strengths. It represents a real-world effectiveness trial evaluating a self-help intervention delivered to quitline clients via mail. The intervention draws on empirical and theoretical research in RP. The study methodology allowed for evaluation of 24 months of outcomes. Finally, the large, diverse sample provided the statistical power to test both main effects, as well as moderating variables.

The primary limitation of this study is related to generalizability. There is considerable variability in the amount and type of services provided by telephone quitlines in the United States and Canada.41 Services may include self-help materials, one or more proactive telephone counseling sessions, various types and amounts of cessation pharmacotherapy, or various combination of the above. The NYSSQL offered at least two proactive telephone counseling sessions, NRT, and educational materials consisting of a cessation guide and information about nicotine withdrawal. The Forever Free booklets may be more effective among quitlines with fewer resources or without pharmacotherapy, as suggested by prior research.26 Given the low cost of the Forever Free booklets, testing this intervention with telephone quitlines that have limited resources and provide low-intensity services may still be warranted. An additional generalizability-related factor is that the study sample consisted of predominantly Caucasian smokers who had some college or technical school education. However, given that there were no outcome differences by racial/ethnic minority status or by level of education, results from this study are likely to generalize to populations consisting of variable race, ethnicity, and education demographics.

Another limitation is the lack of biochemical verification of cessation status due to logistical barriers. However, this decision is consistent with research showing that there is little benefit from inclusion of biochemical verification in low-intensity interventions without strong incentives to report false abstinence.42

In summary, the findings from this study suggest that sending self-help relapse-prevention booklets to all Quitline callers adds little benefit to deterring relapse, and is therefore not recommended. However, selectively sending RP materials to callers explicitly seeking assistance for RP, and those identified as highly dependent on nicotine, may prove to be worthwhile.

Funding

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01CA137357. This work has also been supported in part by the Biostatistics and Survey Methods Core Facilities at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, an NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30CA76292). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Interests

THB has received research support from Pfizer, Inc. KMC has received grant funding from the Pfizer Corporation to study the impact of a hospital based tobacco cessation intervention. He also receives funding as an expert witness in litigation filed against the tobacco industry. No other financial disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported by the authors of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study staff, Krissie Sismilich and Monica Carrington, for their assistance with implementing this study.

References

- 1. Gerber Y, Myers V, Goldbourt U. Smoking reduction at midlife and lifetime mortality risk in men: a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(10):1006–1012. 10.1093/aje/kwr466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Papathanasiou A, Milionis H, Toumpoulis I, et al. Smoking cessation is associated with reduced long-term mortality and the need for repeat interventions after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;13(3):448–550. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280403c68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ. 2000;321(7257):323–329. 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99(1):29–38. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hughes JR, Peters EN, Naud S. Relapse to smoking after 1 year of abstinence: a meta-analysis. Addict Behav. 2008;33(12):1516–1520. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Engstrom PF, Clapper ML, Schnoll RA. Approaches for Smoking Cessation. In: Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR. et al. , eds. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th ed. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lichtenstein E, Zhu S, Tedeschi GJ. Smoking Cessation Quitlines: an underrecognized intervention success story. Am Psychol. 2010;65(4):252–261. 10.1037/a0018598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cummings KM, Fix B, Celestino P, Carlin-Menter S, O’Connor R, Hyland A. Reach, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of free nicotine medication give away programs. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(1):37–43. 0.1097/00124784-200601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cummings KM, Hyland A, Carlin-Menter S, Mahoney M, Willett J, Juster H. Costs of giving out free nicotine patches through a telephone quit line. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17(3):E16–E23. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182113871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kahende JW, Loomis BR, Adhikari B, Marshall L. A review of economic evaluations of tobacco control programs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2008;6(1):51–68. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krupski L, Cummings KM, Hyland A, et al. Cost and effectiveness of combination nicotine replacement therapy in heavy smokers contacting a quitline. J Smok Cessat. 2015; 1–10. 10.1017/jsc.2015.1. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomson T, Helgason AR, Gilljam H. Quitline in smoking cessation: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(4):469–474. 10.1017/S0266462304001370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McAfee TA. Quitlines: a tool for research and dissemination of evidence-based cessation practices. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:S357–367. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carlin-Menter S, Cummings KM, Celestino P, et al. Does offering more support calls to smokers influence quit success? J Public Health Manag Pract. 2011;17(3):E9–15. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318208e730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toll BA, Martino S, Latimer A, et al. Randomized trial: Quitline specialist training in gain-framed vs standard-care messages for smoking cessation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(2):96–106. 10.1093/jnci/djp468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; 19(3) 1–87. 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu S-H, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, et al. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(14):1087–1093. 10.1056/NEJMsa020660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhu S-H, Tedeschi G, Anderson CM, et al. Telephone counseling as adjuvant treatment for nicotine replacement treatment in a “real-world” setting. Prev Med. 2000;31(4):357–363. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Agboola S, Mcneill A, Coleman T, Bee JL. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smoking relapse prevention interventions for abstinent smokers. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1362–1380. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brandon TH, Collins BN, Juliano LM, Lazev AB. Preventing relapse among former smokers: a comparison of minimal interventions via telephone and mail. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(1):103–113. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brandon TH, Meade CD, Herzog TA, Chirikos TN, Webb MS, Cantor AB. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a minimal intervention to prevent smoking relapse: dismantling the effects of content versus contact. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(5):797–808. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chirikos TN, Herzog TA, Meade CD, Webb MS, Brandon TH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a complementary health intervention: the case of smoking relapse prevention. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(4):475–480. 10.1017/S0266462304001382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention: theoretical rationale and overview of the model. In: Marlatt GH, Gordon JR, eds. Relapse Prevention. New York, NY: Guilford; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shiffman S, Shumaker SA, Abrams DB, et al. Models of smoking relapse. Health Psychol. 1986;5(suppl):13–27. 10.1037/0278-6133.5.Suppl.13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sheffer CE, Stitzer M, Brandon TH, Bursac Z. Effectiveness of adding relapse prevention materials to telephone counseling. J Subs Abuse Treat. 2010;39(1):71–77. 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brandon TH, Simmons VN, Meade CD, et al. Self-help booklets for preventing postpartum smoking relapse: a randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):2109–2115. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bandura A, ed. Social Learning Theory. New Jersey, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meade CD, Byrd JC. Patient literacy and the readability of smoking education literature. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(2):204–205. 10.2105/AJPH.79.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Biener L, Abrams DB. Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10(5): 360–365. 10.1037/0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: an analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(2):295–304. 10.1037/0022-006X.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simmons VN, Heckman BW, Ditre JW, Brandon TH. A measure of smoking abstinence-related motivational engagement: development and initial validation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(4):432–427. 10.1093/ntr/ntq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. Client satisfaction questionnaire-8 and service satisfaction scale-30. In: Maruish ME, ed. The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment. New Jersey, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schafer JL, ed. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bernaards CA, Beline TR, Schafer JL. Robustness of a multivariate normal approximation for imputation of incomplete binary data. Stat Med. 2007;26(6):1368–1382. 10.1002/sim.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhu S-H, Anderson CM, Tedeschi G, et al. The California Smokers’ Helpline: Five Years of Experience. La Jolla, CA: University of California; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu S-H, Tedeschi GJ, Anderson CM, Pierce JP. Telephone counseling for smoking cessation: what’s in a call? J Counsel Develop. 1996;75(2): 93–102. 10.1002/j.1556–6676.1996.tb02319.x. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mermelstein R, Cohen S, Lichtenstein E, Baer JS, Kamarck T. Social support and smoking cessation and maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(4):447–453. 10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P. The Hawthorne Effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Research Methodol. 2007;7(1):30. 10.1186/1471-2288-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cummins SE, Bailey L, Campbell S, Koon-Kirby C, Zhu SH. Tobacco cessation quitlines in North America: a descriptive study. Tob Control. 2007;16(suppl 1):i9–i15. 10.1136/tc.2007.020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Benowitz NL, Jacob P, III, Ahijevych K. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(2):149–159. 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]