Abstract

Background

While microtubule destabilizing agents (principally vincristine) are in common use in pediatric oncology, the microtubule stabilizing taxanes are uncommonly used to treat childhood cancers. Cabazitaxel has been reported to have activity superior to that of docetaxel in preclinical models of multidrug-resistant adult cancers, and it was active in patients who had progressed on or after docetaxel. The PPTP conducted a comparison of these two agents against the PPTP in vitro panel and against a limited panel of solid tumor xenografts.

Procedures

Cabazitaxel and docetaxel were tested against the PPTP in vitro cell line panel at concentrations from 0.01 nM to 0.1 µM and in vivo against a subset of the PPTP solid tumor xenograft models at a dose of 10 or 7.5 mg/kg on an every 4 days × 3 I.V. schedule.

Results

In vitro both cabazitaxel and docetaxel had similar potency (median rIC50 0.47 nM and 0.88 nM, respectively) and a similar activity profile, with Ewing sarcoma cells being significantly more sensitive to both agents. In vitro sensitivity to docetaxel inversely correlated with mRNA expression for ABCB1, but the correlation with ABCB1 expression was weaker for cabazitaxel. In vivo cabazitaxel demonstrated significantly greater activity than docetaxel in 5 of 12 tumor models, inducing regressions in 6 models compared with 3 models for docetaxel.

Conclusions

Cabazitaxel demonstrated superior activity compared to docetaxel. The lower cabazitaxel systemic exposure tolerated in humans compared to mice needs to be considered when extrapolating these results to the clinical setting.

Keywords: Preclinical Testing, Developmental Therapeutics, taxane derivatives

INTRODUCTION

Agents targeting microtubules are often used in cancer therapy [1, 2]. Vinca alkaloids (such as vincristine) act as microtubule destabilizers and are commonly used in treating pediatric leukemias and solid tumors [1, 3]. The taxanes, paclitaxel and docetaxel, act to stabilize tubulin structures and are used frequently in treating adult solid tumors [1], but they are uncommonly used in pediatric oncology [4]. The clinical activity of paclitaxel and docetaxel observed in phase 1 studies and in phase 2 studies for children with recurrent solid tumors failed to encourage subsequent clinical evaluations [4–6]. However, occasional responses were observed in these studies against rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and other cancers, and responses to gemcitabine plus docetaxel have been observed in adults and children with sarcomas [7, 8].

Given the established role for taxanes for multiple adult cancers and the activity of tubulin-targeted agents like Vinca alkaloids for childhood cancers, there has been interest in identifying novel agents targeting tubulin that show high activity against childhood cancers. Preclinical studies using pediatric cancer models employing the nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel formulation (nab-paclitaxel) have shown encouraging results [9, 10], but clinical activity against childhood cancers remains to be demonstrated. Preclinical results may not necessarily translate into clinical activity. As an example, Epothilones are natural products with taxane-like microtubule stabilizing activity [2]. A robust study of the epothilone ixabepilone in xenografts of pediatric solid tumors and brain tumors showed promising activity [11], but a phase 2 trial of ixabepilone in refractory pediatric solid tumors did not show evidence of clinical activity [12], although scheduling of drug in preclinical and clinical studies differed considerably. This is in contrast to the NCI Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP) experience with vincristine, which has well known clinical activity in pediatric solid tumors and acute lymphoblastic leukemia and which demonstrated broad-spectrum activity in PPTP in vivo and in in vitro testing [13, 14]. Eribulin, a novel tubulin binding agent that suppresses growth parameters at microtubule plus ends without affecting microtubule shortening also demonstrated high activity in the PPTP in vitro and in vivo models [15], but its clinical activity in pediatric cancers remains to be defined.

Cabazitaxel is a semisythetic taxane that was identified through a large-scale screening process designed to select agents that show consistent activity in both docetaxel-sensitive and docetaxel-resistant cell lines and in vivo models [16, 17]. Cabazitaxel, which is the 7,10 dimethyloxy derivative of docetaxel, demonstrates greater activity than docetaxel in multiple adult solid tumor models with inate or acquired taxane resistance [17]. As taxanes down-regulate androgen receptor expression and signaling in prostate cancer cell lines (providing a potential dual mechanism of action) [18], initial clinical trials of cabazitaxel focused on achieving a registered indication in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) [18]. FDA approval of cabazitaxel in 2010 was based on results from the TROPIC trial in which patients with mCRPC received daily oral prednisone and were randomized to receive either mitoxantrone or cabazitaxel. Overall survival was improved from 12.7 months for patients receiving mitoxantrone to 15.1 months for patients receiving cabazitaxel [19].

A recent preclinical study showed promising activity of cabazitaxel in subcutaneous xenografts of pediatric and adolescent rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma [20]. In this report we further explore the activity of cabazitaxel against pediatric cancers by comparing the effect of cabazitaxel and docetaxel against PPTP in vitro and in vivo models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro testing

In vitro testing was performed using DIMSCAN [21] as previously described in a characterized panel of 24 cell lines [13]. Cells were incubated in the presence of cabazitaxel or docetaxel for 96 hours at concentrations from 0.01 nM to 0.1 µM and analyzed as previously described [13].

In vivo tumor growth inhibition studies

CB17SC scid−/− female mice (Taconic Farms, Germantown NY), were used to propagate subcutaneously implanted kidney/rhabdoid tumors, sarcomas (Ewing, osteosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma), and neuroblastoma [14]. Female mice were used irrespective of the patient gender from which the original tumor was derived. All mice were maintained under barrier conditions and experiments were conducted using protocols and conditions approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the appropriate consortium member. Ten mice were used in each control or treatment group. Tumor volumes (cm3) were determined and responses were determined using three activity measures as previously described [14]. An in-depth description of the analysis methods is included in the Supplemental Response Definitions section.

Statistical Methods

The exact log-rank test, as implemented using Proc StatXact for SAS®, was used to compare event-free survival distributions between treatment and control groups. P-values were two-sided and were not adjusted for multiple comparisons given the exploratory nature of the studies.

Drugs and Formulation

Cabazitaxel and docetaxel were provided to the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program by Sanofi through the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (NCI). Both cabazitaxel and docetaxel were formulated in ethanol, and diluted with an equal volume of polysorbate 80, and brought to volume with 5% dextrose solution USP. Solutions were maintained on ice and administered IV Q4D × 3 at 0.05 ml/10 grams body weight within 20 min of formulation. Cabazitaxel and docetaxel were provided to each consortium investigator in coded vials for blinded testing.

RESULTS

In vitro testing

Cabazitaxel and docetaxel were tested against the PPTP’s in vitro cell line panel at concentrations ranging from 0.01 nM to 0.10 µM using the PPTP’s standard 96 hour exposure period. The median relative IC50 (rIC50) value for the PPTP cell lines for cabazitaxel was 0.47 nM, with a range from 0.14 nM (Ewing sarcoma cell line CHLA-10) to 1.16 nM (neuroblastoma cell line CHLA-136) (Table I). The median relative IC50 (rIC50) value for docetaxel was 0.88 nM, with a range from 0.30 nM (rhabdomyosarcoma cell line Rh18) to 6.15 nM (neuroblastoma cell line NB-EBc1) (Table I). A metric used to compare the relative responsiveness of the PPTP cell lines to cabazitaxel and docetaxel is the ratio of the median rIC50 of the entire panel to that of each cell line. Higher ratios are indicative of greater sensitivity to the test agents and are shown in Figure 1A for cabazitaxel and Figure 1B for docetaxel, by bars to the right of the midpoint line. Linear regression analysis shows a significant correlation between the rIC50 values for the two agents (R2 = 0.64) (Figure 1C). The PPTP had previously tested other microtubule inhibitors (vincristine and eribulin) using the same cell line panel [13, 15]. Linear regression analysis of rIC50 values showed a much lower association between eribulin and cabazitaxel (R2 = 0.26) and especially between vincristine and cabazitaxel (R2 = 0.06).

Table I.

In vitro activity of cabazitaxel and docetaxel against PPTP cell lines

| Cell Line | Histotype | rIC50 (nM) |

Panel rIC50/ Line rIC50 |

Ymin (Observed) |

Estimated Ymin* |

Relative In/Out (Observed Ymin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cabazitaxel | ||||||

| RD | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.51 | 0.92 | 9.9 | 8.6 | 5% |

| Rh41 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.50 | 0.94 | 6.8 | 7.9 | −69% |

| Rh18 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.17 | 2.82 | 51.4 | 50.5 | 12% |

| Rh30 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.18 | 2.55 | 15.0 | 19.2 | −9% |

| BT-12 | Rhabdoid | 0.54 | 0.87 | 4.9 | 5.7 | −40% |

| CHLA-266 | Rhabdoid | 0.42 | 1.12 | 21.5 | 23.0 | −18% |

| TC-71 | Ewing sarcoma | 0.18 | 2.65 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −95% |

| CHLA-9 | Ewing sarcoma | 0.17 | 2.85 | 2.5 | 3.4 | −30% |

| CHLA-10 | Ewing sarcoma | 0.14 | 3.33 | 4.7 | 5.8 | −25% |

| CHLA-258 | Ewing sarcoma | 0.18 | 2.58 | 15.5 | 17.1 | −60% |

| SJ-GBM2 | Glioblastoma | 0.31 | 1.53 | 5.2 | 6.4 | −47% |

| NB-1643 | Neuroblastoma | 0.45 | 1.05 | 1.9 | 2.3 | −91% |

| NB-EBc1 | Neuroblastoma | 0.89 | 0.53 | 3.8 | 4.1 | −83% |

| CHLA-90 | Neuroblastoma | 0.84 | 0.56 | 12.2 | 13.2 | −56% |

| CHLA-136 | Neuroblastoma | 1.16 | 0.41 | 11.4 | 11.1 | −60% |

| NALM-6 | ALL | 0.57 | 0.82 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −99% |

| COG-LL-317 | ALL | 0.44 | 1.07 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −100% |

| RS4;11 | ALL | 0.57 | 0.82 | 1.3 | 0.0 | −91% |

| MOLT-4 | ALL | 0.29 | 1.61 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −98% |

| CCRF-CEM (1) | ALL | 0.57 | 0.83 | 0.2 | 0.0 | −96% |

| CCRF-CEM (2) | ALL | 0.49 | 0.95 | 0.1 | 0.0 | −98% |

| Kasumi-1 | AML | 0.86 | 0.54 | 8.1 | 9.9 | −72% |

| Karpas-299 | ALCL | 0.29 | 1.61 | 4.2 | 6.7 | −46% |

| Ramos-RA1 | NHL | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −100% |

| Median | 0.47 | 1.00 | 4.5 | 5.8 | −65% | |

| Minimum | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −100% | |

| Maximum | 1.16 | 3.33 | 51.4 | 50.5 | 12% | |

| Docetaxel | ||||||

| RD | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.77 | 1.14 | 8.08 | 12.5 | 3% |

| Rh41 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.89 | 0.99 | 7.09 | 9.7 | −68% |

| Rh18 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.30 | 2.93 | 50.00 | 51.5 | 10% |

| Rh30 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 0.51 | 1.71 | 15.26 | 17.0 | −8% |

| BT-12 | Rhabdoid | 0.67 | 1.31 | 4.95 | 5.3 | −40% |

| CHLA-266 | Rhabdoid | 1.19 | 0.74 | 19.43 | 19.2 | −26% |

| TC-71 | Ewing sarcoma | 0.44 | 2.02 | 0.03 | 0.0 | −98% |

| CHLA-9 | Ewing sarcoma | 0.42 | 2.10 | 1.76 | 0.0 | −51% |

| CHLA-10 | Ewing sarcoma | 0.31 | 2.88 | 3.13 | 4.2 | −50% |

| CHLA-258 | Ewing sarcoma | 0.41 | 2.15 | 15.23 | 15.9 | −61% |

| SJ-GBM2 | Glioblastoma | 0.80 | 1.10 | 4.07 | 5.7 | −59% |

| NB-1643 | Neuroblastoma | 1.05 | 0.84 | 2.19 | 0.0 | −90% |

| NB-EBc1 | Neuroblastoma | 6.15 | 0.14 | 3.53 | 0.0 | −85% |

| CHLA-90 | Neuroblastoma | 2.23 | 0.39 | 11.48 | 14.2 | −59% |

| CHLA-136 | Neuroblastoma | 3.84 | 0.23 | 10.16 | 0.0 | −65% |

| NALM-6 | ALL | 1.57 | 0.56 | 0.06 | 0.0 | −98% |

| COG-LL-317 | ALL | 1.27 | 0.69 | 0.02 | 0.0 | −100% |

| RS4;11 | ALL | 1.38 | 0.64 | 1.40 | 0.0 | −91% |

| MOLT-4 | ALL | 0.87 | 1.01 | 0.06 | 0.0 | −99% |

| CCRF-CEM (1) | ALL | 2.04 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.0 | −96% |

| CCRF-CEM (2) | ALL | 1.66 | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.0 | −98% |

| Kasumi-1 | AML | 3.08 | 0.29 | 7.76 | 8.4 | −73% |

| Karpas-299 | ALCL | 0.59 | 1.49 | 4.31 | 6.8 | −45% |

| Ramos-RA1 | NHL | 0.52 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 0.0 | −100% |

| Median | 0.88 | 1.00 | 3.80 | 2.1 | −66% | |

| Minimum | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.0 | −100% | |

| Maximum | 6.15 | 2.93 | 50.00 | 51.5 | 10% | |

Figure 1. Cabazitaxel and docetaxel in vitro activity.

A: Cabazitaxel, B: Docetaxel. The median rIC50 ratio graph shows the relative rIC50 values for the cell lines of the PPTP panel. Each bar represents the ratio of the panel rIC50 to the rIC50 value of the indicated cell line. Bars to the right represent cell lines with higher sensitivity, while bars to the left indicate cell lines with lesser sensitivity; C: Relationship between relative IC50 concentrations for each agent (R2 = 0.64).

The relationship between rIC50 by histotype for cabazitaxel is further examined in Supplemental Table I (top), which shows the median rIC50 values by histotype. The median rIC50 value for Ewing cell lines (0.17 nM) is significantly lower (p=0.01) than that of non-Ewing cell lines (0.51 nM). Conversely, the median rIC50 for neuroblastoma lines (0.87 nM) is significantly greater than that of non-neuroblastoma cell lines (0.43 nM) (p=0.02). The pattern of histotype specificity for docetaxel mirrored that observed for cabazitaxel (Supplemental Table I).

Relative In/Out% values represent the percentage difference between the Ymin value and the estimated starting cell number and either the control cell number (for agents with Ymin > starting cell number) or 0 (for agents with Ymin < estimated starting cell number). Relative In/Out% values range between 100% (no treatment effect) to −100% (complete cytotoxic effect), with a Relative In/Out% value of 0 being observed for a completely effective cytostatic agent. Figure 2A shows that cabazitaxel and docetaxel have similar patterns for Relative In/Out% values, with the acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cell lines showing values approaching −100% (consistent with a high level of cytotoxicity), and with the rhabdomyosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma cell lines more commonly showing values near 0% (consistent with cytostasis). Figure 2B shows that the Ymin% values for cabazitaxel and docetaxel, on which the Relative In/Out% values are based, were highly correlated (R2 = 0.997). The Relative In/Out% values were, as expected, also highly correlated for cabazitaxel and docetaxel (R2 = 0.96, data not shown).

Figure 2. Relative cytotoxic activity in vitro.

A: The Relative In/Out% values compare the relative difference in final cell number compared with the starting cell number for treated cells and for control cells calculated as follows: (Observed Ymin−Y0)/(100−Y0) if Observed Ymin > Y0; and (Observed Ymin−Y0)/(Y0) if Observed Ymin < Predicted Ymin). Y0 is an estimate of the starting cell number derived from determinations of the doubling time for each cell line. Relative In/Out% values range between 100% (no treatment effect) to −100% (complete cytotoxic effect), with a Relative In/Out% value of 0% being observed for a completely effective cytostatic agent. B: Relationship between Ymin% values for docetaxel and cabazitaxel (R2 = 0.997)

Cabazitaxel activity has been shown to be less affected than docetaxel by the activity of the ABCB1 gene product (P-glycoprotein 1, multidrug resistance protein 1) [16, 17]. The relationship in the PPTP cell line panel between ABCB1 expression (as determined by Affymetrix U133 Plus 2 data) and cabazitaxel rIC50 and docetaxel rIC50 is shown in Supplemental Figure I. Although the rIC50 values for both agents were correlated with ABCB1 expression, the strength of the correlation was greater for docetaxel than for cabazitaxel. Additionally, the slope for the relationship was significantly steeper for docetaxel (1.15, 95% confidence interval 0.76 to 1.54) compared to cabazitaxel (0.20, 95% confidence interval 0.11 to 0.29).

In vivo testing

For in vivo testing, models were selected based on their ABCB1 (MDR1) expression levels as well as on their response to the epothilone, ixabepilone. Supplemental Table II provides the response to ixabepilone for the selected models, as well as the relative expression of ABCB1. NB-1691 was the only xenograft among those tested showing markedly elevated ABCB1 expression.

The cabazitaxel and docetaxel testing route and schedule were intravenous (IV) administration using a Q4D × 3 treatment schedule with a total planned observation period of 6 weeks. Prior to commencing efficacy testing, toxicity testing was performed using doses of 7.5 mg/kg and 10.0 mg/kg with 5 mice per treatment cohort. With both doses weight loss between 10% and 19% was observed, although weight recovery was prompt after the administration of the third dose. The 7.5 mg/kg dose was selected for efficacy testing, but due to miscommunication the 10 mg/kg dose was used for the osteosarcoma xenografts and for one neuroblastoma xenograft (NB-1691).

During efficacy testing, the 10 mg/kg dose showed a nominally higher toxicity rate in the cabazitaxel treated group compared to the the docetaxel group treated at 10 mg/kg [2 of 38 (5.3%) versus 0 of 38 (0.0%), respectively]. The 7.5 mg/kg dose was tolerated well for both the cabazitaxel and the docetaxel groups [1 of 87 (1.1%) and 0 of 86 (0%), respectively]. For the sarcoma and Wilms tumor models uniformly treated at 7.5 mg/kg, weight at Days 7 and 14 of treatment was comparably reduced for cabazitaxel and docetaxel (95.3% and 91.3% for cabazitaxel and 97.1% and 94.3% for docetaxel). Weight at days 7 and 14 was lower for both agents at the 10 mg/kg dose (94.2% and 88.4% for cabazitaxel and 95.7% and 89.7% for docetaxel). None of the comparisons of weight by either agent or dose achieved statistical significance.

All tested xenograft models were considered evaluable for efficacy. Complete details of testing are provided in Supplemental Table III, including total numbers of mice, number of mice that died (or were otherwise excluded), numbers of mice with events and average times to event, tumor growth delay, as well as numbers of responses and T/C values.

Cabazitaxel and docetaxel induced significant differences in event-free survival (EFS) distribution compared to control in all of the evaluable solid tumor xenografts except for NB-1691 (7.5 mg/kg dosing) and NB-1643 that were not responsive to either agent and Rh18 tumors treated with docetaxel (Supplemental Table III). For those xenografts with a significant difference in EFS distribution between treated and control groups, the PPTP EFS T/C activity metric additionally requires an EFS T/C value of > 2.0 for intermediate activity which indicates a substantial effect in slowing tumor growth. High activity further requires a reduction in final tumor volume compared to the starting tumor volume. Cabazitaxel induced tumor growth inhibition meeting criteria for high EFS T/C activity in 8 of 11 (73%) solid tumor xenografts evaluable for this metric, while docetaxel met criteria for high activity in 3 of 11 (27%) models evaluable for this metric. For cabazitaxel, Rh18, NB-1643, and NB-1691 (7.5 mg/kg group) met criteria for low EFS T/C activity, while for docetaxel 4 models (Rh18, KT-10, NB-1643, and NB-1691) met criteria for low activity.

A direct comparison of the EFS distributions for cabazitaxel and docetaxel showed that 5 of 9 models in the 7.5 mg/kg treatment groups had significantly longer EFS for cabazitaxel compared to docetaxel (Supplemental Table III). These included xenografts representing Wilms tumor (KT-10), Ewing sarcoma (CHLA-258), and rhabdomyosarcoma (Rh30, Rh30R, and Rh36). Among the remaining 4 models for which the difference in EFS distribution was not significant for cabazitaxel-treated versus docetaxel-treated xenografts, both agents were highly effective for SK-NEP-1 while neither agent was effective against Rh18, NB-1691, or NB-1643. The three osteosarcoma xenografts, all treated at the 10 mg/kg dose, showed similar responses to both agents, with a pattern of either stable disease or slowly developing responses. For NB-1691 treated at 10 mg/kg, the cabazitaxel group had significantly longer EFS compared to the docetaxel group.

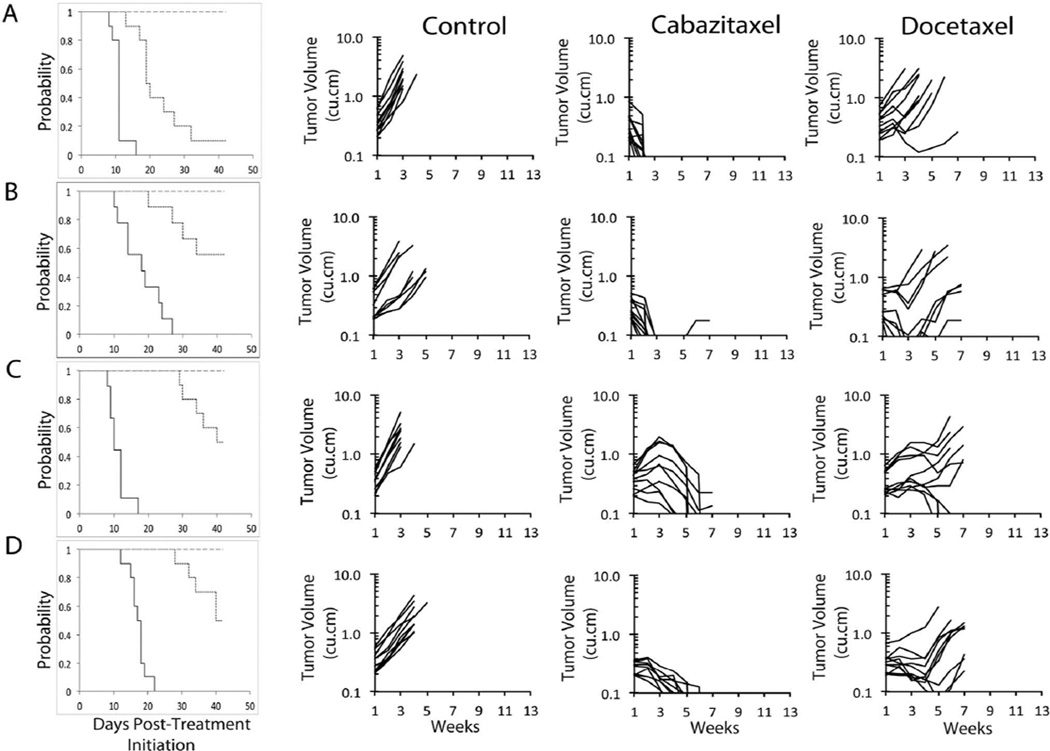

Objective responses [PR, CR, or maintained CR (MCR)] were observed in 6 of 12 solid tumor xenografts treated with cabazitaxel and 4 of 12 models treated with docetaxel. For cabazitaxel, all of the objective responses were maintained complete responses (MCRs), while for docetaxel, only 1 of the objective responses was an MCR. For cabazitaxel, MCRs were observed against multiple histotypes (Wilms tumor, Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and osteosarcoma). Examples of differential responses for tumors treated with cabazitaxel or docetaxel are shown in Figure 3. The objective response results are shown in Figure 4 using a ‘COMPARE’ and heat map formats based on the objective response scoring criteria centered around the midpoint score of 0 that represents stable disease.

Figure 3. Cabazitaxel and docetaxel in vivo objective response activity for the most responsive solid tumors.

A: KT-10 (Wilms tumor), B: CHLA-258 (Ewing sarcoma), C: Rh30 (alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma) and D: Rh36 (embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma): Kaplan-Meier curves for EFS (left; ____ control; ---- cabazitaxel; ..... docetaxel), growth of individual control (left), cabazitaxel (center) and docetaxel (right) treated tumors.

Figure 4.

Left: The colored heat map depicts group response scores. A high level of activity is indicated by a score of 6 or more, intermediate activity by a score of >2 but <6, and low activity by a score of <2. Right: representation of tumor sensitivity based on the difference of individual tumor lines from the midpoint response (stable disease). Bars to the right of the median represent lines that are more sensitive, and to the left are tumor models that are less sensitive. Red bars indicate lines with a significant difference in EFS distribution between treatment and control groups, while blue bars indicate lines for which the EFS distributions were not significantly different.

DISCUSSION

Microtubule destabilizing agents, principally vincristine, have broad clinical and non-clinical activity in childhood cancers and are widely used in treating pediatric solid tumors and acute lymphoblastic leukemia [1, 3]. By contrast, in spite of some encouraging preclinical data, limited clinical trials in pediatric oncology have been undertaken with the tublin-stabilizing agents paclitaxel and docetaxel [4]. The phase 1 and phase 2 trials conducted with these agents showed infrequent objective reponses [4].

One potential limitation for paclitaxel and docetaxel is that the concentration of these agents in tumor cells is decreased by p-glycoprotein (the ABCB1 gene product), which contributes to resistance. Although cabazitaxel is a substrate for p-glycoprotein, the level of resistance induced by p-glycoprotein is less for cabazitaxel than it is for docetaxel [17]. Our data support these prior findings by showing a stronger inverse association between in vitro sensitivity to docetaxel and expression of the ABCB1 gene than observed for cabazitaxel. The latter property of cabazitaxel may be, at least in part, responsible for the greater activity observed for cabazitaxel compared to docetaxel at 10 mg/kg against NB-1691 (the xenograft line with the highest ABCB1 expression among all models tested). However, other mechanisms may also contribute to the greater activity of cabazitaxel over docetaxel. For example, the higher lipophilicity for cabazitaxel compared to docetaxel may result in increased cell penetration through passive influx [16], as illustrated by the more rapid drug uptake for cabazitaxel over docetaxel into MCF7 breast cancer cells (which do not express p-glycoprotein) [22]. While uptake mechanisms may differ for cabazitaxel and docetaxel, the remarkably high correlation (R2=0.997) between the Relative In/Out% values for docetaxel and cabazitaxel is consistent with a shared final common pathway for each agent, as these values reflect the effect of each agent at concentrations producing maximum activity. It was reported that prostate cancer resistant to androgen therapy by virtue of RB1 mutations was more sensitive to cabazitaxel. In vitro, knockdown of RB1 using siRNA marginally sensitized LNCaP cells. However, the effect in this model as a subcutaneous xenograft was more pronounced, although whether knockdown of RB1 altered growth of these cells was not addressed as the appropriate control growth curves were not reported [23]. None of the xenograft models used in the current testing have RB1 mutations. Further, the range of cell sensitivities in vitro to cabazitaxel was small (8.2-fold), hence, it is unlikely that expression profiles would distinguish between more cell lines more sensitive and less sensitive to cabazitaxel.

Pediatric preclinical data have been generated for microtubule stabilizing agents beyond paclitaxel and docetaxel with the hope of finding agents that may produce higher levels of activity against childhood cancers. For example, recent encouraging pediatric preclinical data using the nab-paclitaxel formulation may stimulate clinical trials for this agent [9, 10]. Our results for cabazitaxel are consistent with a previous report describing in vivo activity for cabazitaxel against rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma xenografts and showing greater in vivo activity for cabazitaxel compared to docetaxel [20]. An additional report described the in vivo activity of cabazitaxel against pediatric brain tumor models [24]. The activity for cabazitaxel that we observed is similar to that previously reported for ixabepileone for models against which both agents were tested [11]. For example, the rhabdomyosarcoma xenografts Rh30 and Rh36 and the Ewing sarcoma xenograft SK-NEP-1 were highly responsive to both agents while the neuroblastoma xenografts NB-1643 and NB-1691 were resistant to both agents. Rh18 was more responsive to ixabepilone, while KT-10 was more responsive to cabazitaxel. The ixabepilone example provides a cautionary note for evaluating the clinical significance of both the nab-paclitaxel and the cabazitaxel preclinical results. Despite encouraging preclinical data for ixabepilone [12], this agent did not show activity in a pediatric solid tumor phase 2 study. The scheduling of drug administration was different in the preclinical studies from that evaluated clinically [12], although it is not known whether this contributed to the observed low clinical activity of ixabepilone against childhood cancers.

A key issue in interpreting the clinical significance of in vivo xenograft efficacy data is the relationship between the drug exposure in mice of the tested agent compared to that in humans at tolerated doses. Cabazitaxel is typically administered in the clinic at a dose of 25 mg/m2 every 3 week, and the principal dose-limiting toxicity identified in phase 1 testing was neutropenia [25]. The average area-under-the-curve (AUC) at the 25 mg/m2 dose was 1,038 µg●hr/L [25]. By contrast, two publications have documented that in normal mice the AUC at a dose of 10 mg/kg is approximately 10,000 µg●hr/L [16, 20]. Thus, by extrapolation, the AUC reported here per cycle (Q4D x3) would result in an exposure approximately 24-fold greater than achieved clinically when cabazitaxel was clinically administered at 25 mg/m2 on an every three week schedule.

In summary, we confirm the higher preclinical activity for cabazitaxel over docetaxel against childhood cancer preclinical models when comparable doses of each agent are used. The lower cabazitaxel systemic exposure tolerated in patients compared to mice increases the likelihood that the preclinical results for cabazitaxel are overpredicting for its clinical activity against childhood cancers. The substantial discrepancy between the drug exposure associated with in vivo activity against pediatric solid tumor xenografts in mice and the drug exposure achievable in humans needs to be considered when extrapolating these preclinical results to the clinical setting.

Supplementary Material

Table II.

Summary of in vivo activity of cabazitaxel and docetaxel.

| Line Description |

Agent | Dose (mg/kg) |

Tumor Type | Estimate of Median Time to Event |

P- value1 |

EFS T/C2 |

P- value3 |

Median RTV at End of Study |

Tumor Volume T/C4 |

EFS T/C Activity |

Median Group Response5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KT-10 | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | Wilms | > EP | <0.001 | > 3.9 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.00 | High | MCR |

| KT-10 | Docetaxel | 7.5 | Wilms | 19.6 | <0.001 | 1.8 | >4 | 0.33 | Low | PD2 | |

| SK-NEP-1 | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | Ewing | > EP | <0.001 | > 3.8 | 0.211 | 0.0 | 0.00 | High | MCR |

| SK-NEP-1 | Docetaxel | 7.5 | Ewing | > EP | <0.001 | > 3.8 | 0.0 | 0.03 | High | MCR | |

| CHLA258 | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | Ewing | > EP | <0.001 | > 2.3 | 0.033 | 0.0 | 0.04 | High | MCR |

| CHLA258 | Docetaxel | 7.5 | Ewing | > EP | <0.001 | > 2.3 | 3.8 | 0.18 | Intermediate | PR | |

| Rh30 | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | ALV RMS | > EP | <0.001 | > 4.1 | 0.033 | 0.0 | 0.30 | High | MCR |

| Rh30 | Docetaxel | 7.5 | ALV RMS | > EP | <0.001 | > 4.1 | 0.27 | Intermediate | PD2 | ||

| Rh30R | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | ALV RMS | > EP | <0.001 | > 3.3 | <0.001 | 0.5 | 0.23 | High | SD |

| Rh30R | Docetaxel | 7.5 | ALV RMS | 30.5 | <0.001 | 2.4 | >4 | 0.30 | Intermediate | PD2 | |

| Rh18 | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | EMB RMS | 22.2 | <0.001 | 1.6 | 0.147 | >4 | 0.59 | Low | PD2 |

| Rh18 | Docetaxel | 7.5 | EMB RMS | 18.7 | 0.027 | 1.3 | >4 | 0.77 | Low | PD1 | |

| Rh36 | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | EMB RMS | > EP | <0.001 | > 2.4 | 0.033 | 0.0 | 0.08 | High | MCR |

| Rh36 | Docetaxel | 7.5 | EMB RMS | > EP | <0.001 | > 2.4 | 3.9 | 0.14 | Intermediate | PD2 | |

| NB-1691 | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | Neuroblastoma | 5.1 | 0.312 | 0.9 | 0.405 | >4 | 1.07 | Low | PD1 |

| NB-1691 | Docetaxel | 7.5 | Neuroblastoma | 6.2 | 0.942 | 1.0 | >4 | 0.89 | Low | PD1 | |

| NB-1691 | Cabazitaxel | 10 | Neuroblastoma | 23.9 | <0.001 | 4.1 | <0.001 | >4 | 0.14 | Intermediate | PD2 |

| NB-1691 | Docetaxel | 10 | Neuroblastoma | 6.6 | 0.579 | 1.1 | >4 | 1.02 | Low | PD1 | |

| NB-1643 | Cabazitaxel | 7.5 | Neuroblastoma | 5.0 | 0.083 | 1.1 | 0.944 | >4 | 0.82 | Low | PD1 |

| NB-1643 | Docetaxel | 7.5 | Neuroblastoma | 4.7 | 0.345 | 1.0 | >4 | 0.89 | Low | PD1 | |

| OS-1 | Cabazitaxel | 10 | Osteosarcoma | > EP | <0.001 | > 1.7 | 1.000 | 1.1 | 0.43 | NE | SD |

| OS-1 | Docetaxel | 10 | Osteosarcoma | > EP | <0.001 | > 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.52 | NE | PD2 | |

| OS-17 | Cabazitaxel | 10 | Osteosarcoma | > EP | <0.001 | > 2.1 | 0.195 | 1.0 | 0.30 | High | SD |

| OS-17 | Docetaxel | 10 | Osteosarcoma | > EP | <0.001 | > 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.22 | High | CR | |

| OS-33 | Cabazitaxel | 10 | Osteosarcoma | > EP | <0.001 | > 2.1 | 0.552 | 0.1 | 0.47 | High | MCR |

| OS-33 | Docetaxel | 10 | Osteosarcoma | > EP | <0.001 | > 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.46 | High | CR |

P-value for comparison of the EFS distribution of the test agent to that of untreated controls;

EFS T/C values = the ratio of the median time to event of the treatment group and the median time to event of the respective control group. High activity requires: a) an EFS T/C > 2; b) a significant difference in EFS distributions, and c) a net reduction in median tumor volume for animals in the treated group at the end of treatment as compared to at treatment initiation. Intermediate activity = criteria a) and b) above, but not having a net reduction in median tumor volume for treated animals at the end of the study. Low activity = EFS T/C < 2;

P-value for comparison of the EFS distribution of the cabazitaxel and docetaxel treated groups;

Tumor Volume T/C value: Relative tumor volumes (RTV) for control (C) and treatment (T) mice were calculated at day 21 or when all mice in the control and treated groups still had measurable tumor volumes (if less than 21 days). The T/C value is the mean RTV for the treatment group divided by the mean RTV for the control group. High activity = T/C ≤ 0.15; Intermediate activity = T/C ≤ 0.45 but > 0.15; and Low activity = T/C > 0.45. 3P-value for compassion of the EFS distribution of docetaxel and cabazitaxel;

Objective response measures are described in detail in the Supplemental Response Definitions. PD1 = progressive disease with EFS T/C ≤ 1.5, and PD2 = progressive disease with EFS T/C > 1.5. SD = stable disease. CR = complete response. MCR = maintained complete response.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NO1-CM-42216, CA21765, and CA108786 from the National Cancer Institute and used cabazitaxel supplied by Sanofi.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors consider that there are no actual or perceived conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Table I: Relative IC50 Values by Histotype for cabazitaxel (top) and docetaxel (bottom)

Supplemental Table II. PPTP in vivo models response to Ixabepilone and ABCB1 expression

Supplemental Table III. Efficacy of cabazitaxel and docetaxel in Xenograft Models

Supplemental Figure 1. Correlation between rIC50 concentrations for cabazitaxel and docetaxel and expression of ABCB1 in the in vitro cell line panel.

In addition to the authors this paper represents work contributed by the following: Sherry Ansher, Joshua Courtright, Kathryn Evans, Edward Favours, Danuta Gasinski, Melissa Sammons, Joe Zeidner, Catherine A. Billups, Ellen Zhang, and Jian Zhang.

References

- 1.Jordan MA, Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nature reviews Cancer. 2004;4(4):253–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez EA. Microtubule inhibitors: Differentiating tubulin-inhibiting agents based on mechanisms of action, clinical activity, and resistance. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8(8):2086–2095. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gidding CE, Kellie SJ, Kamps WA, de Graaf SS. Vincristine revisited. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 1999;29(3):267–287. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(98)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andre N, Meille C. Taxanes in paediatric oncology: and now? Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32(2):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurwitz CA, Strauss LC, Kepner J, Kretschmar C, Harris MB, Friedman H, Kun L, Kadota R. Paclitaxel for the treatment of progressive or recurrent childhood brain tumors: a pediatric oncology phase II study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23(5):277–281. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zwerdling T, Krailo M, Monteleone P, Byrd R, Sato J, Dunaway R, Seibel N, Chen Z, Strain J, Reaman G. Phase II investigation of docetaxel in pediatric patients with recurrent solid tumors: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer. 2006;106(8):1821–1828. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee EM, Rha SY, Lee J, Park KH, Ahn JH. Phase II study of weekly docetaxel and fixed dose rate gemcitabine in patients with previously treated advanced soft tissue and bone sarcoma. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2012;69(3):635–642. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rapkin L, Qayed M, Brill P, Martin M, Clark D, George BA, Olson TA, Wasilewski-Masker K, Alazraki A, Katzenstein HM. Gemcitabine and docetaxel (GEMDOX) for the treatment of relapsed and refractory pediatric sarcomas. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2012;59(5):854–858. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner LM, Yin H, Eaves D, Currier M, Cripe TP. Preclinical evaluation of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel for treatment of pediatric bone sarcoma. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/pbc.25062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Marrano P, Kumar S, Leadley M, Elias E, Thorner P, Baruchel S. Nab-paclitaxel is an active drug in preclinical model of pediatric solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19(21):5972–5983. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson JK, Tucker C, Favours E, Cheshire PJ, Creech J, Billups CA, Smykla R, Lee FY, Houghton PJ. In vivo evaluation of ixabepilone (BMS247550), a novel epothilone B derivative, against pediatric cancer models. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11(19 Pt 1):6950–6958. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs S, Fox E, Krailo M, Hartley G, Navid F, Wexler L, Blaney SM, Goodwin A, Goodspeed W, Balis FM, Adamson PC, Widemann BC. Phase II trial of ixabepilone administered daily for five days in children and young adults with refractory solid tumors: a report from the children's oncology group. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16(2):750–754. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang MH, Smith MA, Morton CL, Keshelava N, Houghton PJ, Reynolds CP. National Cancer Institute Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program: Model description for in vitro cytotoxicity testing. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2011;56(2):239–249. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Tucker C, Payne D, Favours E, Cole C, Gorlick R, Kolb EA, Zhang W, Lock R, Carol H, Tajbakhsh M, Reynolds CP, Maris JM, Courtright J, Keir ST, Friedman HS, Stopford C, Zeidner J, Wu J, et al. The pediatric preclinical testing program: Description of models and early testing results. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2006 doi: 10.1002/pbc.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolb EA, Gorlick R, Reynolds CP, Kang MH, Carol H, Lock R, Keir ST, Maris JM, Billups CA, Desjardins C, Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ, Smith MA. Initial testing (stage 1) of eribulin, a novel tubulin binding agent, by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2013;60(8):1325–1332. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vrignaud P, Semiond D, Benning V, Beys E, Bouchard H, Gupta S. Preclinical profile of cabazitaxel. Drug design, development and therapy. 2014;8:1851–1867. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S64940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vrignaud P, Semiond D, Lejeune P, Bouchard H, Calvet L, Combeau C, Riou JF, Commercon A, Lavelle F, Bissery MC. Preclinical antitumor activity of cabazitaxel, a semisynthetic taxane active in taxane-resistant tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19(11):2973–2983. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheetham P, Petrylak DP. Tubulin-targeted agents including docetaxel and cabazitaxel. Cancer J. 2013;19(1):59–65. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3182828d38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen S, Machiels JP, Kocak I, Gravis G, Bodrogi I, Mackenzie MJ, Shen L, Roessner M, Gupta S, Sartor AO. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semiond D, Sidhu SS, Bissery MC, Vrignaud P. Can taxanes provide benefit in patients with CNS tumors and in pediatric patients with tumors? An update on the preclinical development of cabazitaxel. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2013;72(3):515–528. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2214-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frgala T, Kalous O, Proffitt RT, Reynolds CP. A fluorescence microplate cytotoxicity assay with a 4-log dynamic range that identifies synergistic drug combinations. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2007;6(3):886–897. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azarenko O, Smiyun G, Mah J, Wilson L, Jordan MA. Antiproliferative mechanism of action of the novel taxane cabazitaxel as compared with the parent compound docetaxel in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2014;13(8):2092–2103. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Leeuw R, Berman-Booty LD, Schiewer MJ, Ciment SJ, Den RB, Dicker AP, Kelly WK, Trabulsi EJ, Lallas CD, Gomella LG, Knudsen KE. Novel actions of next-generation taxanes benefit advanced stages of prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21(4):795–807. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Girard E, Ditzler S, Lee D, Richards A, Yagle K, Park J, Eslamy H, Bobilev D, Vrignaud P, Olson J. Efficacy of cabazitaxel in mouse models of pediatric brain tumors. Neuro-oncology. 2015;17(1):107–115. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mita AC, Denis LJ, Rowinsky EK, Debono JS, Goetz AD, Ochoa L, Forouzesh B, Beeram M, Patnaik A, Molpus K, Semiond D, Besenval M, Tolcher AW. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of XRP6258 (RPR 116258A), a novel taxane, administered as a 1-hour infusion every 3 weeks in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15(2):723–730. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.