Abstract

Chemical reagents targeting and controlling amyloidogenic peptides have received much attention for helping identify their roles in the pathogenesis of protein-misfolding disorders. Herein, we report a novel strategy for redirecting amyloidogenic peptides into nontoxic, off-pathway aggregates, which utilizes redox properties of a small molecule (DMPD, N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine) to trigger covalent adduct formation with the peptide. In addition, for the first time, biochemical, biophysical, and molecular dynamics simulation studies have been performed to demonstrate a mechanistic understanding for such an interaction between a small molecule (DMPD) and amyloid-β (Aβ) and its subsequent anti-amyloidogenic activity, which, upon its transformation, generates ligand–peptide adducts via primary amine-dependent intramolecular cross-linking correlated with structural compaction. Furthermore, in vivo efficacy of DMPD toward amyloid pathology and cognitive impairment was evaluated employing 5xFAD mice of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Such a small molecule (DMPD) is indicated to noticeably reduce the overall cerebral amyloid load of soluble Aβ forms and amyloid deposits as well as significantly improve cognitive defects in the AD mouse model. Overall, our in vitro and in vivo studies of DMPD toward Aβ with the first molecular-level mechanistic investigations present the feasibility of developing new, innovative approaches that employ redox-active compounds without the structural complexity as next-generation chemical tools for amyloid management.

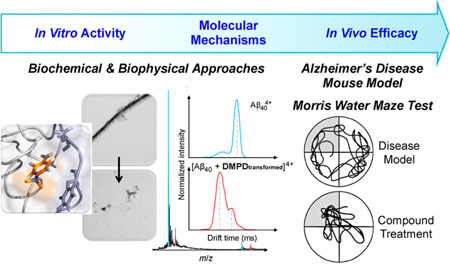

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of all neurodegenerative diseases, has continued to expand in prevalence and remains unabated due to an inadequate understanding of disease pathology, which has significantly impaired efforts to establish effective strategies against the disorder.1–4 As such, fatalities resulting from this deadly malady have continued to increase to the point where today almost one-third of every senior citizen will be affected by AD or a related form of dementia.5 The costs associated with providing the long-term care and resources required by those suffering from AD have also reached staggering levels. This year alone, AD will cost the United States 226 billion dollars, and without intervention, this figure is expected to reach 1.1 trillion by 2050.5 Therefore, it is clear that if this trend is to be suppressed, we must develop a more detailed, molecular-level understanding of the convoluted and multilayered pathology of AD, which will then be able to provide the foundation toward the generation of new strategies against the disease.

Illumination of the molecular mechanisms underlying AD is further obstructed by the absence of completely accurate model systems from which to study the ailment. For example, in vitro analyses often require the experimentalist to narrow the scope of their study to a few potential players (e.g., misfolded proteins) and often deviate from physiological relevancy.1–4 Similarly, in vivo studies are limited by the absence of accurate models that fully mimic human AD.6 Due to these inherent complexities along with the impossibility of addressing every potential factor contributing toward neuronal death in a single report, we have chosen to focus our investigation on the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide, a hallmark of the disease which is known to aggregate to form characteristic senile plaques, and its interplay with metal ions [e.g., Cu(II), Zn(II)].1–4,7–14 Metal ions were incorporated into our studies because of their extensively explored involvement in the facilitation of Aβ aggregation pathways and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via Fenton-like reactions in vitro.2–4,7–14 It is important, however, that we specify that by focusing our analysis on the aggregation and interaction of Aβ and metal ions, we are not implying that these are the sole causes of the disorder.

The evidence suggesting that Aβ is implicated in the pathology of AD is incontrovertible.1–4,7–14 For example, Aβ oligomer load has been closely correlated with cognitive impairment and behavioral tests in transgenic AD mouse models.1,3 Furthermore, multiple cell and transgenic mouse studies have clearly identified Aβ as a contributor to the diminished mitochondrial function observed in AD.3 Aβ has also been indicated to induce kinases responsible for the phosphorylation of tau protein and the subsequent destabilization of microtubules.3 These findings are only a small number of the available reports that link Aβ to AD. The mechanisms by which Aβ may induce cellular death, however, have not been fully understood. In order to advance our understanding of these pathways, the use of chemical tools, capable of elucidating the mechanisms of these processes at the molecular level, will be of indispensable value.2,4,14–22

To this end, we present a redox-active, compact amine derivative, DMPD (N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine; Figure 1a), as a novel chemical tool for redirecting both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ peptides into nontoxic, off-pathway aggregates, via an approach mediated by intramolecular cross-links between compound and peptide. Our strategy, the generation of covalently linked adducts composed of aggregation-prone peptides, was inspired by a recent study suggesting a covalent bond between catechol-type flavonoids and Aβ.23,24 In a previous report, a well-known, redox-active compound, DMPD,25–27 was indicated as a potential molecule of interest, among many others, in a brief calculation-focused screening method and a fluorescence-based assay [i.e., thioflavin-T (ThT) assay].28 Unfortunately, in addition to spectral interference between DMPD and ThT, making results of the assay inconclusive, the report did not present whether DMPD influences the Aβ aggregation pathways or elucidate a mechanistic understanding of its activity with the peptide.28 Through our present studies, we demonstrate the ability of DMPD to redirect both metal-free and metal-induced Aβ aggregation pathways and consequently produce less toxic, off-pathway amorphous aggregates. Biophysical analyses and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations indicate molecular-level interactions of DMPD with both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ in vitro as well as its potential mechanism, based on the formation of intramolecular cross-links between transformed DMPD and Aβ, for redirecting the peptide aggregation. Finally, the efficacy of our approach in biological settings (e.g., living cells, the AD 5xFAD mouse model29) was investigated. Treatment with DMPD mitigates metal-free Aβ-/metal–Aβ-induced toxicity in living cells and reduces the overall cerebral amyloid levels in 5xFAD mice. Additionally, cognitive defects of 5xFAD mice, as evaluated by the Morris water maze task, are significantly improved upon DMPD administration. Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo studies of a redox-active small molecule, along with the molecular-level mechanistic elucidation, illustrate that the strategy to generate Aβ–small molecule adducts could be an effective tactic to control and promote the formation of relatively less toxic, off-pathway aggregates.

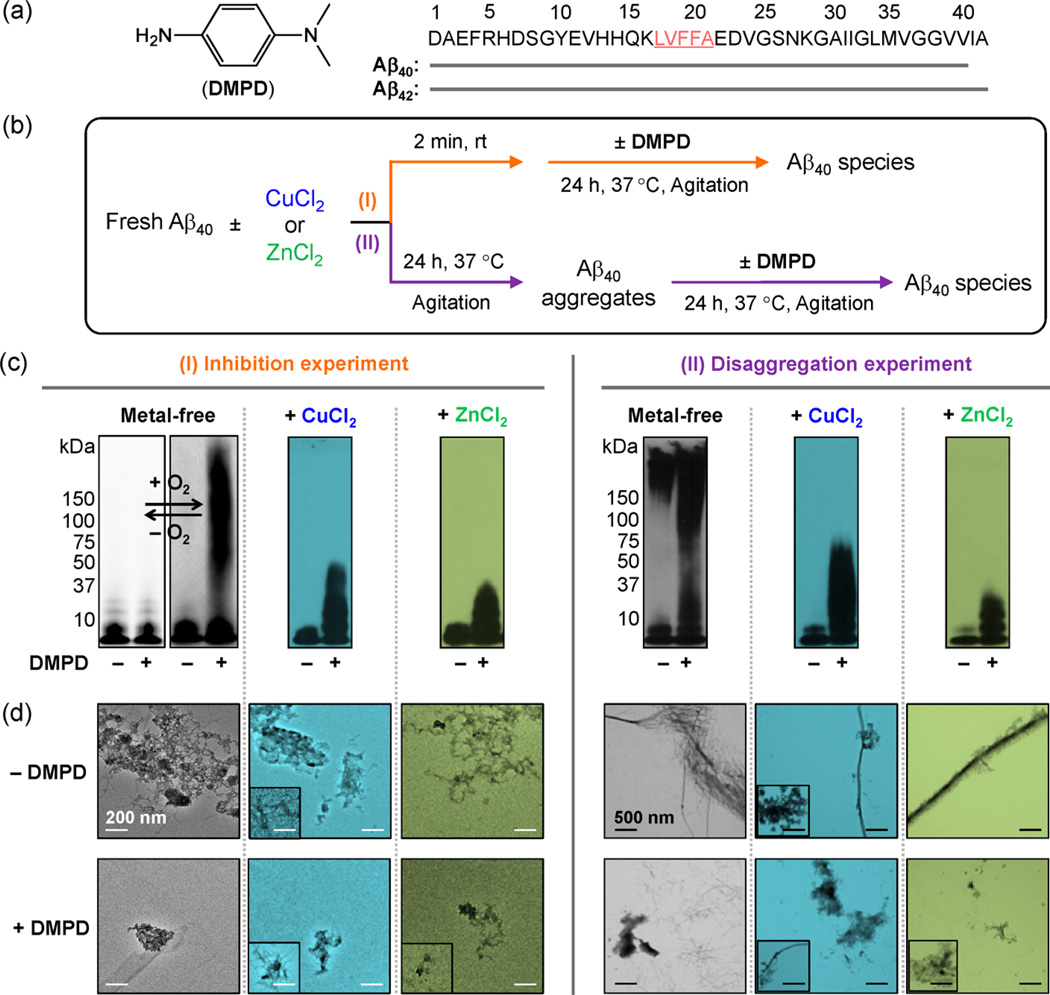

Figure 1.

Effects of DMPD toward metal-free/metal-induced Aβ40 aggregation in vitro. (a) Chemical structure of DMPD and amino acid sequence of Aβ (the self-recognition site is underlined and highlighed in pink). (b) Scheme of the (I) inhibition or (II) disaggregation experiments. The metal-free samples were prepared in both the absence (left) and the presence (right) of O2. (c) Analyses of the resultant Aβ species from (I) and (II) by gel electrophoresis with Western blotting (gel/Western blot) using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10). For the experiment (I), the samples containing metal-free Aβ40 were prepared under anaerobic (left, white background) and aerobic (right, gray background) conditions. Conditions: Aβ (25 µM); CuCl2 or ZnCl2 (25 µM); DMPD (50 µM); 24 h; pH 6.6 (for Cu(II) experiments) or pH 7.4 (for metal-free and Zn(II) experiments); 37 °C; constant agitation. (d) TEM images of the Aβ40 samples prepared under aerobic conditions (from (c)). Inset: Minor species from TEM measurements. White and black scale bars indicate 200 and 500 nm, respecitvely.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Rational Selection of DMPD toward Redirecting Both Metal-Free and Metal-Induced Aβ Aggregation in Vitro and in Biological Systems

Although DMPD is a compact, simple compound, its structure (Figure 1a) includes moieties that are suggested to be potentially essential for interactions with metal-free Aβ, metal–Aβ, and metal ions.2,4,14–16 The overall redox and structural characteristics of DMPD could indicate its direct interactions with both metal-free Aβ or metal–Aβ, as well as its subsequent ability to redirect peptide aggregation pathways via the generation of covalently linked adducts between compound and Aβ, as previously presented for catechol-type flavonoids.23,24 In addition, DMPD is shown to be biologically compatible based on our investigations. First, DMPD is potentially blood–brain barrier permeable and has antioxidant activity similar to that of a water-soluble vitamin E analogue, Trolox (Supporting Information Table S1). Second, as presented in Supporting Information Figure S1, in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), DMPD is relatively stable with an approximate half-life (t1/2) of 1 day. Addition of hydrogen peroxide, however, leads to oxidation of DMPD (its cationic radical25–27) with a t1/2 value of 55 min. Lastly, DMPD has relative metabolic stability. Using FAME software,30 the sites of metabolism were predicted, showing the alkylate aniline nitrogen as a site of metabolism (Supporting Information Figure S1a). The metabolic stability of DMPD was also further analyzed employing human liver microsomes. We observed classic enzyme kinetics showing that the metabolic processing is between 30 and 120 min [t1/2 = 107 min ([DMPD] = 0.5 mM); Vmax, ca. 22.9 nM/min; KM, ca. 2.07 mM; Supporting Information Figure S1]. Overall, DMPD is indicated to have moderate metabolic stability and could be administered for its applications in vivo since its concentration would be much lower than the 2.07 mM KM for liver microsomes.

Effects of DMPD on Both Metal-Free and Metal-Induced Aβ Aggregation in Vitro

The influence of DMPD on the aggregation of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 was probed in the absence and presence of metal ions [i.e., Cu(II), Zn(II)]. Gel electrophoresis with Western blotting (gel/Western blot) using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were employed to analyze the molecular weight (MW) distribution and morphological change of the resultant Aβ species, respectively (Figure 1c,d and Supporting Information Figures S2 and S3).18–22,31 As depicted in Figure 1b and Supporting Information Figure S2a, two different experiments were conducted to assess whether DMPD can either inhibit the formation of metal-free/metal-treated Aβ aggregates (I, inhibition experiment) or disassemble preformed metal-free/metal-associated Aβ aggregates (II, disaggregation experiment). Generally, small molecules able to inhibit the formation of Aβ fribrils or disassemble preformed Aβ aggregates will generate a distribution of smaller Aβ species that can penetrate into the gel matrix and will produce a significant amount of smearing compared to compound-free controls. Aβ samples without treatment with compounds contain large Aβ aggregates (i.e., mature fibrils), which can be observed by TEM, but are too big to enter the gel matrix (restricted to the entrance where the sample is loaded) and therefore do not produce smearing or bands in the gel/Western blot.

In the inhibition experiment (I, Figure 1b), different MW distributions were observed for DMPD-treated Aβ40 with and without metal ions compared to the untreated analogues. TEM images revealed the generation of small amorphous Aβ aggregates with respect to the large clusters of fibrils generated in the absence of DMPD (Figure 1c,d). DMPD exhibited a similar ability to inhibit aggregate formation with Aβ42 (Figure S2b). In the disaggregation experiment (II, Figure 1b), DMPD indicated more noticeable effects on the transformation of preformed metal-free Aβ40 and metal–Aβ40 aggregates than for the Aβ42 conditions visualized by gel/Western blot (Figure 1c, right; Supporting Information Figure S2b, right); however, the generation of shorter, more dispersed fibrils, relative to the DMPD-untreated Aβ42 controls, was indicated by TEM (Figure S2b,c). Moreover, in order to determine the effect of DMPD on Aβ aggregation in a heterogeneous in vitro environment, the inhibition experiment was performed in a cell culture medium. Upon treatment of DMPD to Aβ40 in a cell culture medium, a distinguishable variation in the MW distribution of Aβ species was still observed (Supporting Information Figure S3), but this distribution was different from that shown in a buffered solution (Figure 1c, left). Therefore, these results support that the small monodentate ligand, DMPD, is able to redirect both metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ species into off-pathway, relatively smaller and/or less structured peptides aggregates, which has been suggested to be less toxic,16,20,21 in a buffered solution and a heterogeneous matrix.

Proposed Mechanism of DMPD’s Control against Aβ Aggregation Pathways

(i) Interaction of DMPD with Metal-Free Aβ Monomers

The interaction of DMPD with metal-free Aβ monomers was examined by 2D NMR spectroscopy and MD simulations (Figure 2a–c). Two-dimensional band selective optimized flip-angle short transient heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation (SOFASTHMQC) NMR experiments were first employed to identify the interaction of DMPD with monomeric Aβ40. When DMPD was titrated into 15N-labeled Aβ40, relatively noticeable chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) were shown for six amino acid residues (particularly for L17, F20, G33, G37, V39, and V40; Figure 2a,b). These residues in the self-recognition (residues 17–21) and C-terminal hydrophobic regions (Figure 1a) are reported to be crucial for Aβ aggregation and cross-β-sheet formation via hydrophobic interactions.10,16 The CSP presented for V40 may be due to intrinsic C-terminal disorder rather than interaction with DMPD.31 The distribution of observed CSPs suggests that DMPD could interact with the amino acid residues in Aβ40 near the self-recognition and hydrophobic regions.

Figure 2.

Interactions of DMPD with monomeric Aβ and fibrillar Cu–Aβ, observed by 2D NMR spectroscopy and Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy, respectively. (a) 2D 1H–15N SOFAST-HMQC NMR investigation of DMPD with 15N-labeled Aβ40. (b) Chemical shift perturbations of Aβ40 were determined upon addition of DMPD (Aβ/DMPD = 1:10). On the chemical shift plot, the dashed and dotted lines represent the average CSP and one standard deviation above the average, respectively. Relatively noticeable CSPs were observed around the hydrophobic residues of the peptide. *Residues could not be resolved for analysis. (c) Molecular dynamics simulations of the Aβ40–DMPD complex. DMPD and Aβ40 are shown to interact directly with the hydrophobic region of the Aβ40 monomer in its lowest energy conformation (see Supporting Information Figure S3). The chemical structure of DMPD is colored as follows: carbon, orange; hydrogen, white; nitrogen, blue. The self-recognition site of Aβ40 is highlighted in light violet. (d) Left: X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) region of the Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectrum of DMPD-incubated Cu(I)- (red) and Cu(II)-loaded (blue) Aβ42 fibrils. Top right (blue): Magnitude FT and FF (inset) extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of DMPD-incubated Cu(II)-loaded Aβ42 fibrils showing the experimental data (solid line), simulated spectrum (dashed line), and difference spectrum (dotted line). Shell #1 (N scatterer): n = 2.3(2); r = 1.889(3) Å; σ2 = 0.0041(4) Å2; ε2 = 0.93. Bottom right (red): Magnitude FT and FF (inset) EXAFS of DMPD-incubated Cu(I)-loaded Aβ42 fibrils showing the experimental data (solid line), simulated spectrum (dashed line), and difference spectrum (dotted line). Shell #1 (N scatterer): n = 2.2(2); r = 1.882(4) Å; σ2 = 0.0033(1) Å2; ε2 = 0.85.

To further probe the interaction between metal-free, monomeric Aβ40 and DMPD, docking and MD simulation studies32,33 were also performed. Simulations indicate multiple interactions (Figure 2c and Supporting Information Figure S4): (i) a potential binding pocket is formed through hydrogen bonding (2.08 Å) of the amine group (–NH2) of DMPD with the O atom of the backbone carbonyl between L17 and V18; (ii) the aromatic ring of DMPD associates with G38 via a N–H–π interaction (3.16 Å); (iii) the methyl group (–CH3) of the dimethylamino moiety of DMPD further stabilizes the Aβ–DMPD interaction by the C–H–π (with the aromatic ring of F19) interaction (4.10 Å). The observation from docking and MD simulation investigations was in agreement with the NMR findings (vide supra). Thus, 2D NMR and docking/MD simulation studies demonstrate the direct interaction of DMPD with metal-free Aβ species, as suggested from the results of both inhibition and disaggregation experiments above (Figure 1 and Supporting Information Figure S2), along with the mass spectrometric (MS) analysis (vide infra, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Analysis of the resulting species upon interaction of Aβ40 with DMPD or BQ by mass spectrometry and ion mobility–mass spectrometry (IM–MS), as well as a proposed mechanism. (a) MS analysis showing the complex formation of Aβ40 (25 µM) with DMPDtransformed (50 µM) (red lines) in the 4+ and 5+ charge states ([Aβ + DMPDtransformed]4+ and [Aβ + DMPDtransformed]5+) (i). IM–MS was applied to the 4+ charge state to resolve the conformational rearrangement of Aβ40 upon addition and conversion of DMPD to DMPDtransformed (ii). Extracted arrival time distributions support the existence of two resolvable structural populations [collision cross section (CCS) data, inset tables]. The interaction with DMPDtransformed trapped the peptide in a more packed conformation (dominant peak = 1) when compared to the apo form (dominant peak = 2). (b) MS analysis showing the complex formation of Aβ40 (25 µM) with BQ (50 µM) supports that BQ binds readily to the peptide (red) (i). In line with the DMPD data presented above, BQ-containing samples support a mass gain of 104 Da attributed to covalent binding with K16 (Supporting Information Figure S8). IM–MS was applied to the 4+ charge state to resolve the conformational rearrangement of Aβ40 upon binding BQ. Extracted arrival time distributions indicate the existence of three resolvable structural populations (CCS data, inset table) (ii). The first two of these conformations support, within least-squares error analysis, CCS values consistent with the DMPD-bound data (a). (c) Comparison of tandem MS/MS sequencing using the quadrupole isolated 5+ charge state (trap collision energy 90 V) of Aβ405+ (top) and [Aβ + DMPDtransformed]5+ (bottom). Analysis of these data in addition to the MS and IM–MS supports the attachment of DMPDtransformed to Aβ40 through a covalent modification of the peptide via K16, resulting in an observed mass shift of 103.93 ± 0.04 Da calculated from internal monoisotopic calibration data sets. (d) Proposed mechanistic pathways between DMPD and Aβ. DMPD may undergo an oxidative transformation under aerobic conditions to generate a cationic imine (CI)–Aβ complex (1). CI could then generate BQI (shown in 2) through hydrolysis. Once hydrolyzed, BQI is proposed to undergo further hydrolytic conversion to generate BQ (shown in 3). Our MS studies indicate that BQ forms covalently bound protein–ligand adducts (4) that are capable of forming intramolecular cross-links (5) that trap Aβ in an altered conformational geometry compatible with our IM–MS data set.

(ii) Interaction of DMPD with Copper–Aβ Monomers and Fibrils

Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) was applied to Cu(I)- and Cu(II)-loaded Aβ42 monomers and fibrils to gain insights into the nature of the interaction between copper–Aβ complexes and DMPD. The XAS data for Cu(I)-loaded Aβ42 fibrils following DMPD incubation are consistent with a linear two-coordinate Cu(I)(N/O)2 environment (Figure 2d, red). The X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) region of the XAS spectrum exhibited a prominent pre-edge feature at 8985.2(2) eV corresponding to the Cu (1s → 4pz) transition. Such a feature is characteristic of linear Cu(I).34 Analysis of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) region yielded a model consistent with the copper center ligated to two N or O ligands at 1.88 Å. We note that the identity of the ligands to the Cu(I) center could not be definitively determined. Although there are peaks in the magnitude Fourier transformed EXAFS spectrum in the range of r′ = 2.0–4.0 Å that may result from multiple scattering pathways from histidine imidazole rings, they could not be modeled as such. Surprisingly, the Cu(II)-loaded Aβ42 fibrils treated with DMPD yielded nearly identical XAS data, indicating the complete reduction of Cu(II) to a linear two-coordinate Cu(I)(N/O)2 center (blue, Figure 2d). This reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I) is not a result of photoreduction in the X-ray beam. Cu(II) fibrils (or monomers; vide infra) show no indication of photoreduction under identical experimental conditions,34,35 while studies of DMPD-incubated Cu(II) fibrils do not present photochemistry following repeated EXAFS scans under the experimental conditions employed (i.e., the Cu(II) is already reduced to Cu(I) prior to X-ray exposure) (Supporting Information Figure S5).

Copper-loaded Aβ42 monomers incubated with DMPD afforded a result dramatically different than that of the DMPD-untreated samples. In the absence of DMPD, XAS studies showed a spectrum for the Cu(II)-loaded Aβ42 monomers consistent with a square-planar Cu(II)(N/O)4 metal center with two imidazole ligands to Cu(II), while the Cu(I)-loaded Aβ42 monomers contained copper within a linear bis-His coordination environment.34 The XAS data for Cu(II)-loaded Aβ42 monomers following DMPD incubation were indicative of a complex mixture of reduced Cu(I) and oxidized Cu(II) centers. The reduced samples following treatment with DMPD presented that Cu(I) was also contained in a mixture of coordination environments and geometries, making it impossible to yield a physically meaningful solution to the EXAFS data. The different behaviors of copper-loaded Aβ42 monomers versus fibrils could be the result of different incubation times necessitated to avoid monomer aggregation or could be indicative of different fundamental chemistry with DMPD. Taken together, the overall observations from the XAS studies suggest the possible redox interaction of the small monodentate ligand (DMPD) with copper–Aβ complexes.

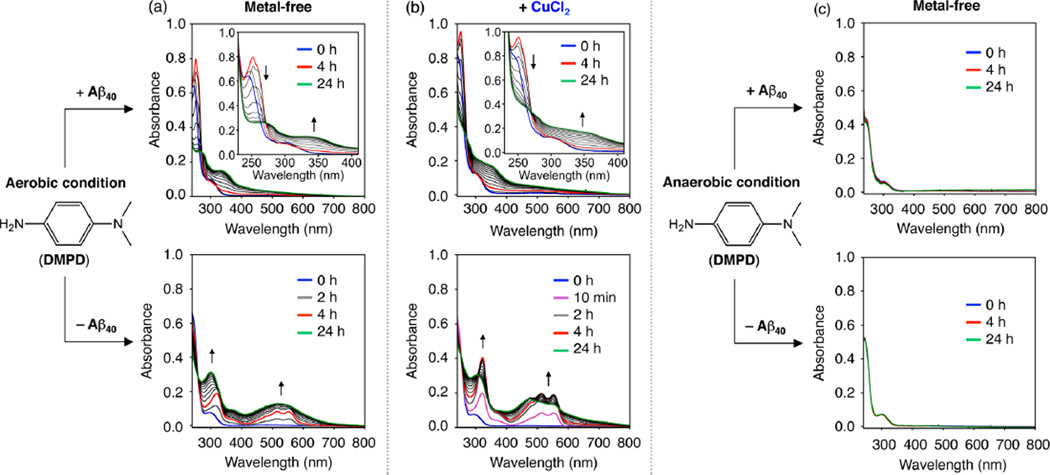

(iii) Transformation of DMPD in the Absence and Presence of Aβ and Metal Ions

To elucidate how DMPD redirects Aβ peptides into less toxic, off-pathway unstructured Aβ aggregates, the chemical transformation of DMPD with Aβ was analyzed under various conditions, in addition to its interactions with metal-free and metal-bound Aβ (vide supra). Time-dependent optical changes of DMPD were first monitored in the absence and presence of Aβ40 with and without CuCl2 in buffered solutions (Figure 3). DMPD treated with Aβ40 in both the absence and the presence of Cu(II) exhibited spectral shifts, different from the Aβ40-free condition (Figure 3a,b). The optical bands at ca. 513 and 550 nm, indicative of the formation of a cationic radical of DMPD25–27 through an oxidative degradation route (Figure 3a,b, bottom), were not observed even after a 24 h incubation of DMPD with Aβ (Figure 3a,b, top). Upon addition of DMPD into a solution containing Aβ40, a red shift in the optical band of DMPD (from 295 to 305 nm) immediately occurred (Supporting Information Figure S6). Upon incubation over 4 h, a new optical band at ca. 340 or 350 nm with an isosbestic point at ca. 270 nm began to grow in (Figure 3a,b, top). These optical bands at ca. 250 and 340 or 350 nm are expected to be indicative of generating a possible adduct of benzoquinoneimine (BQI) or benzoquinone (BQ) with proteins (or peptides) via amine or thiol groups, respectively.23,24,27,36–41 The absence of a clean isosbestic point at the early incubation time points is most likely due to the formation of BQ from DMPD and possibly some contribution from the production of transient complexes between Aβ and cationinc imine (CI) or BQI (vide infra). The UV–vis spectrum of BQ (Supporting Information Figure S7a) is identical to the optical spectra of DMPD with Aβ40 at 2 and 4 h under aerobic conditions, indicating that DMPD is transformed into BQ before the bands at 250 and 340 or 350 nm begin to grow in, indicative of the covalent adduct formation with Aβ. Furthermore, Aβ40 treated to a solution of BQ under identical conditions exhibits one clean isosbestic point over the course of the 24 h experiment (Supporting Information Figure S7b). These results support that the optical changes at the early time points are mainly caused by the generation of BQ from DMPD. Overall, DMPD could be transformed through a different pathway in the presence of Aβ40, potentially producing a modified DMPD conjugate with Aβ40, compared to the Aβ40-absent case.

Figure 3.

Transformation of DMPD with or without Cu(II) and/or Aβ40, monitored by UV–vis. (a,b) UV–vis spectra of DMPD with or without CuCl2 in the absence and presence of Aβ under aerobic conditions. (c) UV–vis spectra of DMPD with or without Aβ under anaerobic conditions. Blue, red, and green lines correspond to incubation for 0, 4, and 24 h, respectively. Conditions: Aβ (25 µM); CuCl2 (25 µM); DMPD (50 µM); pH 6.6 (for Cu(II) experiments) or pH 7.4 (for metal-free experiments); room temperature; no agitation. (a,c) DMPD ± Aβ40; (b) [DMPD + CuCl2] ± Aβ40.

In order to gain a better understanding on the spectrophotometric observations indicative of the transformation of DMPD when Aβ is present (vide supra), additional studies were carried out. First, the UV–vis spectra of DMPD were measured in an anaerobic environment with or without Aβ to ascertain the involvement of dioxygen (O2) in the conversion of DMPD. Previous studies report that DMPD can be singly or doubly oxidized to form a cationic radical or a cationic quinoid species, respectively.25–27 The spectral alterations of DMPD, apparent in an O2 atmosphere in both the absence and presence of Aβ40, were not observed in an anaerobic condition even after 24 h incubation (Figure 3c). In addition, modulation of Aβ aggregation by DMPD was not observed under the anaerobic condition, distinguishable from that under the aerobic setting (Figure 1c, left). Furthermore, inhibition and disaggregation experiments of BQ with Aβ40 and Aβ42 were performed in the absence and presence of metal ions (Supporting Information Figure S8). BQ exhibited an ability to control and alter the MW distribution of Aβ40 and Aβ42 with and without metal ions in a very similar manner to that which was observed for DMPD. Therefore, O2 is necessary for the transformation of DMPD (DMPDtransformed; e.g., BQ) and the capability of DMPDtransformed to redirect Aβ aggregation into less toxic, off-pathway amorphous Aβ aggregates.

(iv) Analysis of Aβ– DMPDtransformed Complexes

MS analysis of DMPD-treated Aβ40 samples was further performed in order to identify the formation of Aβ40–ligand complexes. New peaks appeared corresponding to the addition of 103.93 ± 0.04 Da to Aβ (Figure 4a, i) proposed to be a covalently bound conversion product of DMPD (e.g., BQ; shown as 5 in Figure 4d). To support our proposed mode of Aβ–DMPD interaction, via the transformation of DMPD, the interactions of Aβ40 with the structurally homologous BQ were examined under identical experimental conditions. Our data indicate that BQ binds to Aβ40 (Figure 4b, i), with a mass shift that is consistent with DMPD incubations (104.1 ± 0.1 Da).

Tandem MS (MS/MS) in conjunction with collision-induced dissociation (CID) for the 5+ ligand-bound charge state was carried out to determine the nature of the Aβ40–DMPDtransformed (Figure 4c) and Aβ40–BQ complexes detected (Supporting Information Figure S9). MS/MS data support that both DMPDtransformed and BQ covalently link to Aβ40 via K16, with observed masses consistent with the above analysis. While this ligated mass difference is too small to support a single covalent bond formation between Aβ and DMPDtransformed/BQ (106.1 Da expected due to the release of two protons upon the formation of an Aβ–DMPDtransformed covalent bond), it does agree well with the generation of a second covalent bond between Aβ and DMPDtransformed or BQ (104.1 Da expected from the concomitant loss of two additional protons upon the formation of the second covalent bond). These data therefore support that DMPDtransformed or BQ is capable of cross-linking Aβ, which is consistent with the data previously published for α-synuclein.24 Based on this conclusion, we sought to confirm if DMPDtransformed or BQ is capable of forming inter- and/or intramolecular cross-links using MS/MS. BQ-bound Aβ40 dimer dissociation data indicate that BQ primarily forms intramolecular cross-links (Supporting Information Figure S10).

In addition, IM–MS studies of the 4+ charge state were carried out in order to assess the Aβ-bound-state conformers adopted. When compared to the Aβ control, Aβ–DMPDtransformed complexes possessed a significantly decreased ion mobility (IM) arrival time, indicative of a more compact Aβ40 structure (Figure 4a, ii). Consistent with these data, Aβ40–BQ binding also leads to a similar reduction in IM arrival time, again supporting the production of a more compact species than the form adopted by the compound-untreated Aβ (Figure 4b, ii). Combining these data with observations from our MS/ MS analysis, we conclude that the DMPDtransformed or BQ cross-linking traps Aβ in a relatively compact conformational state that is likely off-pathway with respect to amyloid fibril formation.

(v) Proposed Mechanism

Based on these optical and MS results, the covalent bond formation within Aβ–DMPDtransformed complexes could occur via a possible mechanistic pathway, as described in Figure 4d. In the presence of Aβ under aerobic conditions, DMPD could first undergo a two-electron oxidative transformation to generate a CI–Aβ complex (1). CI could be converted via hydrolysis to BQI (shown in 2) that could further hydrolyze its imine to generate BQ (shown in 3). BQ is then capable of forming a covalently bound Aβ–BQ adduct through interactions with a primary amine containing residue (4; Aβ + 106.1 Da), such as K16, that further cross-links to an additional residue with a similar functional group (5; Aβ + 104.1 Da), consistent with our MS studies and BQ–protein conjugates previously reported.37–41 The covalent complexation of Aβ with BQ could direct the structural compaction, suggested from IM–MS analysis (Figure 4a,b), and could account for DMPD’s redirection of peptide aggregation pathways into amorphous Aβ aggregates,16,20,21 as found in the gel/Western blot and TEM studies (vide supra).

Attenuation of Metal-Free Aβ-/Metal–Aβ-Induced Toxicity in Living Cells by DMPD

The regulation of metal-free Aβ-/metal–Aβ-triggered cytotoxicity by DMPD was examined using human neuroblastoma SK-N-BE(2)-M17 (M17) cells. DMPD was incubated for 24 h with M17 cells pretreated with Aβ40 in both the absence and the presence of Cu(II) or Zn(II). Viability was increased by ca. 10–20% when DMPD was introduced to metal-free Aβ40- or metal–Aβ40-treated M17 cells, relative to the untreated cells (Supporting Information Figure S11), as measured by the MTT assay. Note that DMPD displayed low toxicity in the range of the tested concentrations (0–100 or 0–50 µM in the absence and presence of metal ions, respectively; >80% cell survival; Supporting Information Figure S11a–c). Thus, DMPD could ameliorate cytotoxicity induced by metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ.

In Vivo Efficacy of DMPD against Amyloid Pathology and Cognitive Impairment

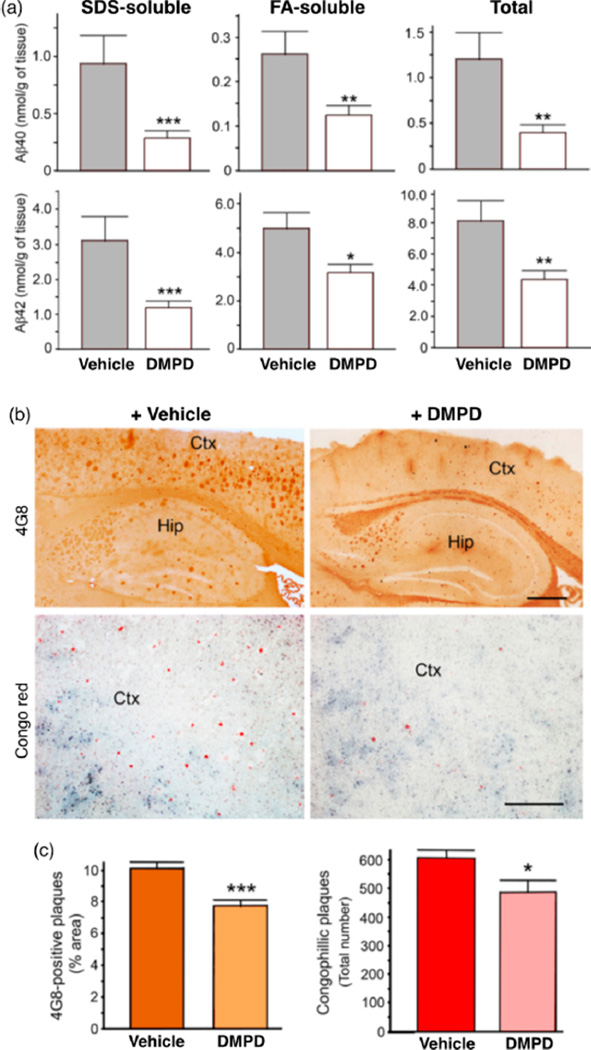

In order to validate the beneficial effects of DMPD on AD pathogenesis in vivo, we administered the compound to 5xFAD mice via the intraperitoneal route at 1 mg/kg/day for 30 days from 3 months of age. After 30 total daily treatments of DMPD, the mice were subjected to biochemical analysis for cerebral amounts of Aβ40/Aβ42 and histopathological evaluations of the amyloid deposition load. 5xFAD mice were selected for this study because they develop early and severe phenotypes of AD and behavioral dysfunction.29 At the conclusion of the compound treatment period, there was no significant difference in gross appearance or body weight between the vehicle- and DMPD-treated 5xFAD mice (Supporting Information Figure S12).

Quantification of cerebral Aβ peptides by the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) revealed that the total levels of Aβ40/Aβ42 containing PBS-, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-, and formic acid (FA)-soluble Aβ species, which represent soluble, moderately soluble, and completely insoluble Aβ species, respectively, were decreased by ca. 66 and 46%, respectively, compared to the vehicle-treated 5xFAD mice (Figure 5a). The levels of SDS-soluble Aβ40/Aβ42 were more drastically reduced by DMPD (ca. 69 and 61%, respectively) than those of FA-soluble Aβ40/Aβ42 levels (ca. 52 and 37%, respectively). Furthermore, substantial reductions in amyloid deposits were detected in 5xFAD mice treated with DMPD, determined by analyzing the loads of amyloid precursor protein (APP)/Aβ-immunoreactive 4G8- and Congo-red-stained compact amyloid plaques (by ca. 23 and 20%, respectively) (Figure 5b,c). Overall, these results indicate that DMPD is able to delay or reverse the amyloid pathogenesis in the brain of AD model mice.

Figure 5.

Reduction of cerebral amyloid pathology by DMPD in the 5xFAD mice. After the total 30 daily i.p. injections of vehicle or DMPD (1 mg/kg/day), the brain tissues were collected from the 5xFAD mice at 4 months of age. (a) Bars denote the amounts of SDS-soluble, FA-soluble, or total (PBS + SDS + FA) Aβ40/Aβ42 peptides in the whole brains, which were calculated from three independent sandwich Aβ ELISA assays (n = 14–17). (b) Representative microscopic images of 4G8-immunostained (brown) or Congo-red-stained (red) brain sections of 5xFAD mice show that DMPD significantly reduced the burden of amyloid deposits in the brain. Ctx, cortex; Hip, hippocampus. Scale bar = 100 µm. (c) Load of 4G8-immunoreactive amyloid deposits and the total number of congophilic amyloid plaques in the microscopic photographs of the identical cortical areas (b) were measured in five brain sections taken from each animal. All values represent mean ± SEM (n = 7). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, or ***P < 0.001 by unpaired two-tail t-test.

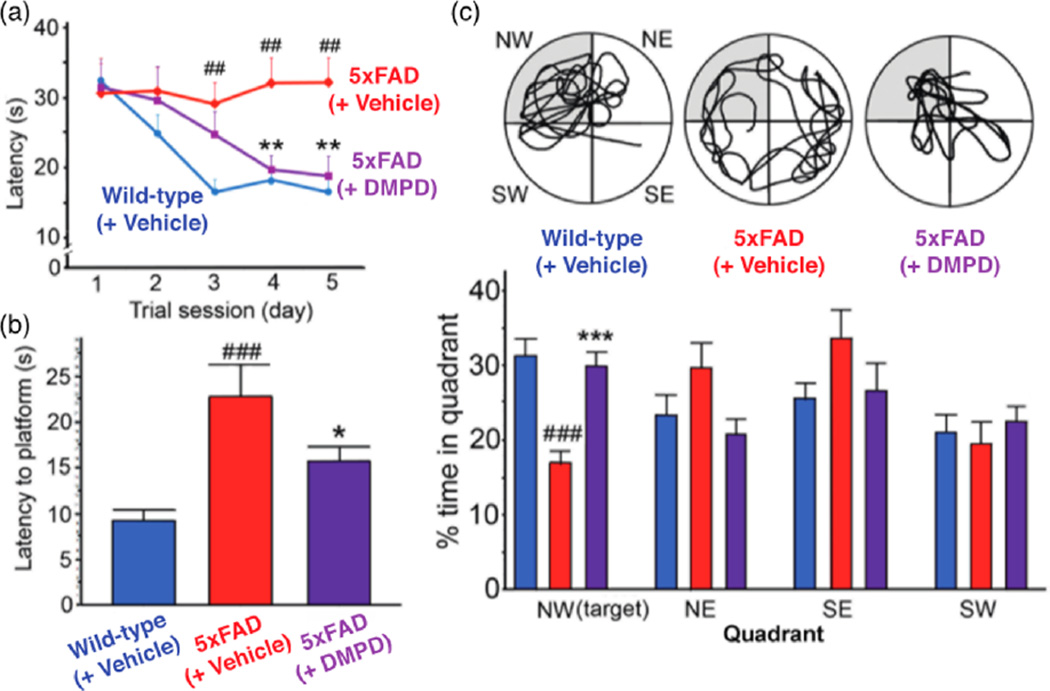

To evaluate the capacity of DMPD to improve cognitive deficits in AD model mice, we tested 4 month old 5xFAD mice employing the Morris water maze (MWM) test for spatial learning and memory during the final five consecutive days of compound treatment. As demonstrated previously,22,29 the 5xFAD mice exhibited impaired spatial learning, showing enhanced difficulty in locating the hidden escape platform in a pool of water compared to their littermate, wild-type mice (Figure 6a). In contrast, the repetitive administration of DMPD prominently improved the learning and memory capability in the 5xFAD mice, relative to those of the vehicle-treated wild-type mice (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Cognitive enhancement by DMPD in the 5xFAD AD mouse model. Using the Morris water maze task, spatial learning and memory activities were compared in the 5xFAD and their littermate wild-type mice after 30 consecutive vehicle or DMPD (1 mg/kg/day, i.p.) treatments. (a) Escape latency time was measured daily for the final 5 days of the drug treatment. (b) Probe trials were performed on the day of the final treatment to assess the time the mice spent to reach the escape platform. (c) Top circular images display the representative swimming paths for the mice to locate the escape platform in the water maze for 60 s. Bottom graphs show how long they spent in the target quadrant (NW, highlighted in gray). The statistical comparisons were performed between 5xFAD and their wild-type littermate mice with vehicle (#) or between consecutive vehicle and DMPD treatments in 5xFAD mice (*), according to the one-way ANOVA followed by a student–Neuman–Keuls post-hoc test. *P < 0.05, **,##P < 0.01 or **,###P < 0.001 (n = 17 for wild-type mice or n = 14 for vehicle- or DMPD-treated 5xFAD mice).

Three hours after the final MWM test, we performed the probe trials, where the escape platform was removed and the mice located its previous position in the water for 60 s, representing their performance of long-term memory retention. DMPD-treated animals took distinguishably less time to reach the platform area and spent significantly more time in the target quadrant (northwest, NW), where the platform had been hidden, than did the vehicle-treated 5xFAD mice (Figure 6b,c). Therefore, our behavioral analysis suggests that DMPD is capable of rescuing cognitive defects in 5xFAD mice.

CONCLUSION

AD continues to present a major socioeconomic burden to our society. The absence of treatments and reliable diagnostics for this disease has demanded significant efforts to be made toward the identification of its underlying origins. For this aspect, the development of chemical tools capable of discerning and/or regulating pathogenomonic factors of interest has been critical for the establishment of our current understanding of AD and will prove to be a central resource as we continue to unravel the intricacies of the disorder.

For instance, the use of small molecular tools (i.e., oligomer stabilizers) able to specifically interact with and conformationally modulate small, soluble Aβ has been important for establishing oligomers as pathological factors.4 The adverse effects of metal ion dyshomeostasis and miscompartmentalization in AD have been validated by utilizing ionophores [e.g., clioquinol (CQ), PBT2] that bind and chauffeur metal ions [i.e., Cu(II), Zn(II)] from extracellular Aβ plaques across the plasma membrane, where it induces a signaling pathway, ultimately activating matrix metalloproteinases, among other enzymes, which assists in the breakdown and clearance of metal-free and metal-bound Aβ plaques.4,42,43 Furthermore, a metal–Aβ-specific tool, L2-b, has been designed to provide direct, in vivo evidence of the potential role of metal-bound Aβ species in AD pathogenesis.19,22 Chemical tools have even been utilized to address the challenges associated with determining the interconnections between multiple facets of AD.4,16,21 A multifunctional ligand (ML) was designed to elucidate some of these pathological factors (e.g., metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ aggregation, oxidative stress) associated with neuronal death in AD.21 Collectively, these results not only identify the vital value of chemical tools to elaborate our comprehension of the disorder but also assist in the further identification of novel pathways to investigate.

In the current study, a compact chemical tool, DMPD, is presented for the redirection of Aβ aggregation in the absence and presence of metal ions into nontoxic, off-pathway aggregates through a novel approach (i.e., intramolecular cross-links with aggregation-prone peptides upon transformation of a redox-active small molecule). DMPD’s reactivity could be related to its interactions with metal-free Aβ and metal–Aβ, along with its redox characteristics, as indicated through multiple biophysical approaches. Mechanistically, DMPD is observed through optical and MS analyses to modulate peptide aggregation pathways through its oxidation and successive hydrolytic transformations to generate more structurally compact quinoid–peptide adducts, compared to the compound- untreated Aβ, through intramolecular covalent cross-linking (i.e., Aβ–BQ). Moreover, the site-specific covalent modification of Aβ via primary amine-containing residues, such as K16, a critical residue for the formation of cross-β-sheet structures within the self-recognition sequence of the peptide,1–4,8–11 could further illuminate DMPD’s reactivity in vitro. DMPD was also evaluated in living cells and in vivo to determine the efficacy and beneficial effects associated with its administration in biological settings. Particularly, the ELISA quantification of the cerebral amyloid content of DMPD-treated 5xFAD mice showed a significant reduction in SDS-soluble forms of Aβ40 and Aβ42 (ca. 60–70% reductions), which are indicative of toxic, soluble pools of Aβ peptides.44–46 When evaluated by FA-soluble Aβ40/Aβ42 levels and amyloid plaque loads,46 the nontoxic amyloid deposits/aggregates were relatively less influenced by DMPD (ca. 20–50% reductions). Therefore, these in vivo analyses also support that DMPD could preferentially influence on the toxic soluble forms of Aβ peptides with the less reactivity toward the insoluble amyloid aggregates or deposits. In addition, memory and learning capabilities of 5xFAD mice were restored upon DMPD treatment as evaluated by the Morris water maze task. Still, further investigations to address remaining questions, such as the specificity of DMPD to generate protein cross-links and the location and time of DMPD’s transformation in vivo, are warranted.

Taken together, the findings of DMPD’s reactivity with the amyloidogenic peptide, Aβ, presented in this work, demonstrate novel, pivotal principles that can be applied toward amyloid aggregation control and the establishment of further chemical tools: (i) formation of intramolecular cross-links between small molecules and peptides may be an effective method to control the self-assembly of amyloidogenic peptides; (ii) effective strategies can still be developed without the need to build up chemical complexity, shown presently within the field.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and Methods

All reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received unless otherwise stated. N,N-Dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Aβ40 and Aβ42 were purchased from AnaSpec (Fremont, CA, USA) (Aβ42 = DAEFRHDSGYEVHHQKL-VFFAEDVGSNKGAIIGLMVGGVVIA). An Agilent 8453 UV–visible (UV–vis) spectrophotometer (Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to measure optical spectra. Anaerobic reactions were performed in a N2-filled glovebox (Korea Kiyon, Bucheon-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). TEM images were taken using a Philips CM-100 transmission electron microscope (Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) or a JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope (UNIST Central Research Facilities, Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, Ulsan, Republic of Korea). Absorbance values for cell viability assay were measured on a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). All IM–MS experiments were carried out on a Synapt G2 (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). NMR studies of DMPD with and without Zn(II) were carried out on a 400 MHz Agilent NMR spectrometer. NMR studies of Aβ with DMPD were conducted on a 900 MHz Bruker spectrometer equipped with a TCI triple-resonance inverse detection cryoprobe (Michigan State University, Lansing, MI, USA).

Aβ Aggregation Experiments

Experiments with Aβ were conducted according to previously published methods.18–22 Aβ40 or Aβ42 was dissolved in ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH, 1% v/v aq), aliquoted, lyophilized overnight, and stored at −80 °C. For experiments described herein, a stock solution of Aβ was prepared by dissolving lyophilized peptide in 1% NH4OH (10 µL) and diluting with ddH2O. The concentration of Aβ peptides in the solution was determined by measuring the absorbance of the solution at 280 nm (ε = 1450 M−1 cm−1 for Aβ40; ε = 1490 M−1 cm−1 for Aβ42). The peptide stock solution was diluted to a final concentration of 25 µM in Chelex-treated buffered solution containing HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (20 µM); pH 6.6 for Cu(II) samples; pH 7.4 for metal-free and Zn(II) samples] and NaCl (150 µM). For the inhibition studies, DMPD [50 µM; 1% v/v dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)] was added to the samples of Aβ (25 µM) in the absence and presence of a metal chloride salt (CuCl2 or ZnCl2, 25 µM) followed by incubation at 37 °C with constant agitation for 24 h. For the disaggregation studies, Aβ with and without metal ions was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with constant agitation prior to the treatment with a compound (50 µM). The resulting Aβ aggregates were incubated with DMPD for 24 h at 37 °C with constant agitation.

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blot

The samples from the inhibition and disaggregation experiments were analyzed by gel electrophoresis with Western blotting using an anti-Aβ antibody (6E10).18–22 Each sample (10 µL) was separated on a 10–20% Tris-tricine gel (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA), and the protein samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, which was blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA, 3% w/v, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T; 1.0 mM Tris base, pH 8.0, 1.5 mM NaCl) for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated with a primary antibody (6E10, Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA; 1:2000) in a solution of 2% w/v BSA (in TBS-T) overnight at 4 °C. After being washed with TBS-T (3×, 10 min), the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:5000; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) in 2% w/v BSA (in TBS-T) was added for 1 h at room temperature. SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) was used to visualize protein bands.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Samples for TEM were prepared according to previously reported methods.18–22 Glow-discharged grids (Formar/carbon 300 mesh, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) were treated with Aβ samples from the inhibition and disaggregation experiments (5 µL) for 2 min at room temperature. Excess buffer was removed by blotting carefully with filter paper and then washed twice with ddH2O. Each grid was incubated with uranyl acetate staining solution (1% w/v ddH2O, 5 µL) for 1 min. Excess stain was blotted off, and the grids were air-dried at room temperature for at least 20 min. Images from each sample were taken on a Philips CM-100 (80 kV) or a JEOL JEM-2100 TEM (200 kV) at 25 000× magnification.

Computational Procedure

A multistep computational strategy was utilized to explore Aβ40–DMPD interactions. In the first step, 100 ns MD simulations in an aqueous solution were conducted to obtain the equilibrated structure of the Aβ40 monomer. These simulations were performed using the GROMACS program (version 4.0.5)47 and GROMOS96 53A6 force field.48 The starting structure of the Aβ40 monomer was extracted from the NMR structures determined in aqueous SDS micelles at pH 5.1 (model 2, PDB 1BA4).49 The root mean square deviations indicated that the system reached the equilibration during the time frame of the simulations. In the next step, to include the flexibility of the Aβ40 monomer into the docking procedure, 100 snapshots were taken at 1 ns intervals throughout the simulation. These snapshots were used for the rigid docking of the DMPD molecule using the AutoDock Vina 1.1.2 software.50 In this procedure, the receptor was kept fixed, but the ligand was allowed to change its conformation. The DMPD molecule was built using the GaussView program (B3LYP/Lanl3DZ)51,52 and optimized at the level of theory using the Gaussian03 program.53 In the docking procedure, the size of the grid was chosen to occupy the whole receptor–ligand complex. Each docking trial produced 20 poses with an exhaustiveness value of 20. The docking procedure provided 2000 poses. Based on binding energies and the composition of interacting sites, 20 distinct poses were selected for short-term (5 ns) MD simulations in an aqueous solution. From these 20 different simulations, five structures were derived and further 20 ns simulations were performed using the same program and force field. These simulations provided a binding site that includes L17, F19, and G38 residues of the Aβ40 monomer. The tools available in the GROMACS program package and the YASARA software (v. 13.2.2)54 were utilized for analyzing trajectories and simulated structures.

For all simulations, the starting structures were placed in a truncated cubic box with dimensions of 7.0 × 7.0 × 7.0 nm. This dismissed unwanted effects that may arise from the applied periodic boundary conditions. The box was filled with single-point-charge water molecules. Few water molecules were replaced by sodium and chloride ions to neutralize the system. The starting structures were subsequently energy-minimized with a steepest descent method for 3000 steps. The results of these minimizations produced the starting structure for the MD simulations. The MD simulations were then carried out with a constant number of particles (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T) [i.e., NPT ensemble]. The SETTLE algorithm was used to constrain the bond length and angle of the water molecules,55 while the LINCS algorithm was used to constrain the bond length of the peptide.56 The particle-mesh Ewald method was implemented to treat the long-range electrostatic interactions.57 A constant pressure of 1 bar was applied with a coupling constant of 1.0 ps. The peptide, water molecules, and ions were coupled separately to a bath at 300 K with a coupling constant of 0.1 ps. The equation of motion was integrated at each 2 fs time steps using the leapfrog algorithm.58

Two-Dimensional SOFAST-HMQC NMR Spectroscopy

NMR titration experiments were performed following a previously reported method.20,21,31 NMR samples were prepared with 15N-labeled Aβ40 (rPeptide, Bogart, GA, USA) which was lyophilized in 1% NH4OH by resuspending the peptide in 100 µL of 1 mM NaOH (pH 10). The peptide was then diluted with 200 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 1 M NaCl, D2O, and water to yield a final peptide concentration of 80 µM. Each spectrum was obtained using 256 complex t1 points and a 1 s recycle delay at 4 °C. The 2D data were processed using TopSpin 2.1 (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). Resonance assignments were carried out by computer-aided resonance assignment using published assignments for Aβ as a guide.59,60 Compiled chemical shift perturbation was calculated using the following equation:

Cu K-Edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy

Aβ42 was monomerized as previously described.61,62 Aβ42 fibrils were grown according to established protocols.63 Following monomerization or fibrillization, all samples were handled under an anaerobic atmosphere (N2) in a COY anaerobic chamber (COY Laboratory, Grass Lake, MI, USA). Aβ42 was dissolved in a 4:1 mixture of 10 mM N-ethylmorpholine buffer (pH 7.4) and glycerol (glycerol is used as a deicing agent) followed by addition of 1 equiv of CuCl2. Aβ42 monomers were maintained at 5 °C and all procedures performed rapidly to avoid aggregation. Following the addition of CuCl2, 2 equiv of ascorbate was treated with the resulting samples to reduce the Cu(II)-loaded Aβ42 peptides to Cu(I). DMPD (2 equiv; in DMSO) was then introduced to each solution. Final Aβ42 concentrations were 250 µM. DMPD was incubated with the copper-loaded fibrils for 24 h. To avoid aggregation (confirmed by gel permeation chromatography studies),61,62 copper-loaded Aβ42 monomers were incubated for 15 min.

Following incubation with DMPD, the solutions were injected into Lucite sample holders with Kapton tape windows and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. All data were recorded on beamline X-3b at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratories, Upton, NY, USA). Samples were maintained at ~18 K throughout data collection by means of a He Displex cryostat. Energy monochromatization was accomplished with a Si(111) double crystal monochromator, and a low-angle Ni mirror was used for harmonic rejection. Data were collected as fluorescence spectra using a Canberra 31 element Ge solid-state detector with a 3 µm Ni filter placed between the sample and detector and calibrated against a simultaneously collected spectrum of Cu foil (first inflection point 8980.3 eV). Count rates were between 15 and 30 kHz and deadtime corrections yielded no improvement to the quality of the spectra. Data were collected in 5 eV steps from 20 to 200 eV below the edge (averaged over 1 s), 0.5 eV steps from 20 eV below the edge to 30 eV above the edge (averaged over 3 s), 2 eV steps from 30 to 300 eV above the edge (averaged over 5 s), and 5 eV steps from 300 eV above the edge to 13 k (averaged over 5 s). Each data set represents the average of 16 individual spectra. Known glitches were removed from the averaged spectra. The X-ray beam was repositioned every four scans, and no appreciable photodamage/photoreduction was noted. Data were analyzed as previously reported using the software packages EXAFS123 and FEFF 7.02. Errors are reported as ε2 values.64,65

Mass Spectrometric Studies

All IM–MS experiments were carried out on a Synapt G2 (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Samples were ionized using a nanoelectrospray source operated in positive ion mode. MS instrumentation was operated at a backing pressure of 2.7 mbar and a sample cone voltage of 40 V. Data were analyzed using MassLynx 4.1 and DriftScope 2.0 (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The m/z scale was calibrated using 20 mg/mL aqueous cesium iodide. Accurate mass values for covalently bound ligands were calculated using the monoisotopic peak difference between apo- and ligand-bound states. CCS measurements were calibrated externally using a database of known protein and protein complex CCS values in helium66,67 with errors reported as the least-square analysis output for all measurements. This least-square analysis combines inherent calibrant error from drift tube measurements (3%), the calibration R2 error, and two times the replicate standard deviation error. Lyophilized Aβ40 (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA, USA) was prepared at a concentration of 25 µM in 1 mM ammonium acetate (pH 7.0). Aliquots of Aβ40 were then incubated with or without 50 µM DMPD or BQ (1% v/v DMSO) for 24 h at 25 °C without constant agitation. After incubation, all samples were lyophilized overnight prior to resuspension of the samples in hexafluoro-2-propanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) ([Aβ40] = 50 µM) and sonicated under pulse settings for 5 min. Samples were diluted 50% to a final Aβ40 concentration of 25 µM, using 1 mM ammonium acetate (0.5 mM final concentration) immediately prior to mass analysis.

Animals and Drug Administration

Animal studies using the 5xFAD mouse model of AD were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Care and Use of the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center (Seoul, Korea). 5xFAD transgenic mice overexpressing mutant human APP695 [K670N/M671L (Swedish), I716 V (Florida), and V717I (London)] and PSEN1 (M146L and L286 V) are characterized by early development of pathological marks of AD, such as Aβ deposits, neurodegeneration, and behavioral disabilities.29 5xFAD mice were produced and maintained on a B6/SJL hybrid background with free access to chow and drinking water under a 12 h light/dark cycle.

In this study, female and male 5xFAD mice were daily administered with freshly prepared vehicle (1% v/v DMSO in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) or DMPD (1 mg/kg of body weight) by intraperitoneal injection for 30 days using Ultra-Fine II insulin syringes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), starting from 3 months of age. The animals were weighed immediately before the injection. After the final injection and behavioral assessment, the mice were sacrificed under deep anesthesia. A necropsy was performed to evaluate the drug-induced systemic damage.

Tissue Preparation

The right cerebral hemispheres were snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen for biochemical analyses. The 12 µm thick sagittal sections were collected from the left hemispheres using a cryostat (HM550; Microm, Walldorf, Germany) and mounted onto 1% poly-l-lysine-coated glass slides for histological evaluations.

Aβ40/Aβ42 Quantification

The right hemispheres were subjected to sandwich ELISA assays for quantitative measurement of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the whole brain according to previously described methods.22,68 Briefly, the protein homogenates were prepared in PBS (pH 7.4) containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in 2% SDS (aq) and then in 70% formic acid by serial centrifugations. The EC buffer-diluted protein fractions were measured using the human Aβ40/Aβ42 ELISA kit (Invitrogen), where FA fractions were neutralized with 1 M Tris (pH 11.0). The colorimetric quantifications were determined at 450 nm with the Synergy H1 hybrid microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA), and the cerebral Aβ40/Aβ42 levels were calculated as moles per gram of wet brain tissue.

Quantification of Aβ Plaques

In order to examine the extracellular Aβ deposits, immunohistochemistry was conducted on the brain sections using an anti-human Aβ(17–24) antibody (4G8, 1:1000; Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA). After immunological reactions with 4G8 and biotinylated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), the tissue sections were developed with 0.015% diaminobenzidine and 0.001% H2O2 (in PBS; Vector Laboratories) and examined under a light microscope (Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). In addition, the congophillic amyloid plaques were detected by staining the tissues with Accustain Congo Red amyloid staining solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The loads of amyloid deposits in the cortex were given as the percent area of 4G8-immunoreactive deposits or the total number of congophilic plaques in the randomly selected cortex areas.

Behavioral Evaluation

Spatial learning and memory performance was tested using the MWM task.22 The maze consisted of a circular water pool with a cylindrical platform (15 cm in diameter) hidden 0.5 cm under the surface of opaque water at the center of a target quadrant. The mice experienced three trials every day to swim and locate the hidden platform for a maximum of 60 s, which were performed at 3 h after each drug injection over a period of 5 consecutive days starting on the day of the 26th drug injection. The time and swimming track spent to reach the platform were analyzed on a SMART video tracking system (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). Three hours after the final MWM task, the mice entered the water again to swim without the platform for 60 s, and the time spent in each quadrant area was recorded.

Statistics

All values are presented as the means ± standard errors of the mean (SEMs). Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired t-test or the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a student–Neuman–Keuls post-hoc test. Differences with P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of Michigan Protein Folding Disease Initiative (to A.R., B.T.R., and M.H.L.) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government [NRF-2014S1A2A2028270 (to M.H.L. and A.R.); NRF-2014R1A2A2A01004877 (to M.H.L.)]; the 2015 Research Fund (Project Number 1.140101.01) of Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) and the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning of Korea (15-BD-0403) (to M.H.L.); the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, Republic of Korea (2015–7012) and the Basic Science Research Program, National Research Foundation of Korea, Ministry of Education, Republic of Korea (NRF-2012R1A1A2006801) (to J.-Y.L.); the National Science Foundation (NSF) (CHE-1362662) (to J.M.S.); an NIH NCI award (R21CA185370) (to E.J.M.); the NSF (Grant Number 1152846) (to R.P.); the Global Ph.D. Fellowship (GPF) programs of the NRF funded by the Korean government (NRF-2014H1A2A1019838) (to Y.N.). All X-ray absorption studies were performed at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) in the Brookhaven National Laboratory. Use of the NSLS was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886. Cu K-edge studies were preformed on beamline X3-b, which is supported through the Case Center for Synchrotron Biosciences, which is funded through the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIH P30-EB-009998). We thank the UC Technology Accelerator for funding and an Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award, NIH/NCR R Grant Number 1UL1RR026314-01. We also thank Dr. Akiko Kochi and Thomas Paul for assistance for TEM measurement (Aβ40 samples) and MD simulations, respectively.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

- Descriptions of the TEAC assay, the PAMPA-BBB assay, metabolic stability measurements, and cell viability studies, Table S1, and Figures S1–S12 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiti F, Dobson CM. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck MW, Pithadia AS, DeToma AS, Korshavn KJ, Lim MH. Ligand Design in Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry. Chapter 10. New York: Wiley; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakob-Roetne R, Jacobsen H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3030–3059. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derrick JS, Lim MH. Chem Bio Chem. 2015;16:887–898. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer's Dementia. 2015;11:332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bales KR. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2012;7:281–297. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.666234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Bush AI. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2004;3:205–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viles JH. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012;256:2271–2284. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeToma AS, Salamekh S, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:608–621. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15112f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kepp KP. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:5193–5239. doi: 10.1021/cr300009x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rauk A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2698–2715. doi: 10.1039/b807980n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Que EL, Domaille DW, Chang CJ. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1517–1549. doi: 10.1021/cr078203u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faller P, Hureau C, La Penna G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:2252–2259. doi: 10.1021/ar400293h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Telpoukhovskaia MA, Orvig C. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:1836–1846. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35236b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez-Rodríguez C, Telpoukhovskaia M, Orvig C. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012;256:2308–2332. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savelieff MG, DeToma AS, Derrick JS, Lim MH. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:2475–2482. doi: 10.1021/ar500152x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez LR, Franz KJ. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:2177–2187. doi: 10.1039/b919237a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hindo SS, Mancino AM, Braymer JJ, Liu Y, Vivekanandan S, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16663–16665. doi: 10.1021/ja907045h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi J-S, Braymer JJ, Nanga RPR, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:21990–21995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006091107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyung S-J, DeToma AS, Brender JR, Lee S, Vivekanandan S, Kochi A, Choi J-S, Ramamoorthy A, Ruotolo BT, Lim MH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:3743–3748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220326110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S, Zheng X, Krishnamoorthy J, Savelieff MG, Park HM, Brender JR, Kim JH, Derrick JS, Kochi A, Lee HJ, Kim C, Ramamoorthy A, Bowers MT, Lim MH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:299–310. doi: 10.1021/ja409801p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck MW, Oh SB, Kerr RA, Lee HJ, Kim SH, Kim S, Jang M, Ruotolo BT, Lee J-Y, Lim MH. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:1879–1886. doi: 10.1039/c4sc03239j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato M, Murakami K, Uno M, Nakagawa Y, Katayama S, Akagi K-i, Masuda Y, Takegoshi K, Irie K. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:23212–23224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.464222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H-T, Lin D-H, Luo X-Y, Zhang F, Ji L-N, Du H-N, Song G-Q, Hu J, Zhou J-W, Hu H-Y. FEBS J. 2005;272:3661–3672. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung Y-C, Su YO. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2009;56:493–503. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evmiridis NP, Sadiris NC, Karayannis MI. Analyst. 1990;115:1103–1107. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modestov AD, Gun J, Savotine I, Lev O. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2004;565:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meek AR, Simms GA, Weaver DF. Can. J. Chem. 2012;90:865–873. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, Maus E, Shao P, Craft J, Guillozet-Bongaarts A, Ohno M, Disterhoft J, Van Eldik L, Berry R, Vassar R. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirchmair J, Howlett A, Peironcely JE, Murrell DS, Williamson MJ, Adams SE, Hankemeier T, van Buren L, Duchateau G, Klaffke W, Glen RC. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013;53:2896–2907. doi: 10.1021/ci300487z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savelieff MG, Liu Y, Senthamarai RRP, Korshavn KJ, Lee HJ, Ramamoorthy A, Lim MH. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:5301–5303. doi: 10.1039/c3cc48473d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook NP, Ozbil M, Katsampes C, Prabhakar R, Martí AA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:10810–10816. doi: 10.1021/ja404850u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Echeverria V, Zeitlin R, Burgess S, Patel S, Barman A, Thakur G, Mamcarz M, Wang L, Sattelle DB, Kirschner DA, Mori T, Leblanc RM, Prabhakar R, Arendash GW. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:817–835. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-102136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shearer J, Szalai VA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:17826–17835. doi: 10.1021/ja805940m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.See the Supporting Information.

- 36.Corbett JF. J. Chem. Soc. B. 1969:213–216. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z, Li X, Wu Y, Tang Y, Ma S. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1999;464:181–186. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher AA, Labenski MT, Malladi S, Chapman JD, Bratton SB, Monks TJ, Lau SS. Toxicol. Sci. 2011;122:64–72. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fisher AA, Labenski MT, Malladi S, Gokhale V, Bowen ME, Milleron RS, Bratton SB, Monks TJ, Lau SS. Biochemistry. 2007;46:11090–11100. doi: 10.1021/bi700613w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bittner S. Amino Acids. 2006;30:205–224. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanzlik RP, Harriman SP, Frauenhoff MM. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994;7:177–184. doi: 10.1021/tx00038a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bush AI, Tanzi RE. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crouch PJ, Savva MS, Hung LW, Donnelly PS, Mot AI, Parker SJ, Greenough MA, Volitakis I, Adlard PA, Cherny RA, Masters CL, Bush AI, Barnham KJ, White AR. J. Neurochem. 2011;119:220–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, Mclntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinerman JR, Irizarry M, Scarmeas N, Raju S, Brandt J, Albert M, Blacker D, Hyman B, Stern Y. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:906–912. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.7.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJC. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oostenbrink C, Villa A, Mark AE, Van Gunsteren WF. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1656–1676. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coles M, Bicknell W, Watson AA, Fairlie DP, Craik DJ. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11064–11077. doi: 10.1021/bi972979f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trott O, Olson AJ. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becke AD. Phys. Rev. A. At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1988;38:3098–3100. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, Millam JM, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Barone V, Mennucci B, Cossi M, Scalmani G, Rega N, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Klene M, Li X, Knox JE, Hratchian HP, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Ayala PY, Morokuma K, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Zakrzewski VG, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Strain MC, Farkas O, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cui Q, Baboul AG, Clifford S, Cioslowski J, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Gonzalez C, Pople JA. Gaussian 03. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.; 2004. revision C.02. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krieger E, Vriend G. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:315–318. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyamoto S, Kollman PA. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:952–962. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. J. Comput. Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hockney RW, Goel SP, Eastwood JW. J. Comput. Phys. 1974;14:148–158. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vivekanandan S, Brender JR, Lee SY, Ramamoorthy A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;411:312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoo SI, Yang M, Brender JR, Subramanian V, Sun K, Joo NE, Jeong S-H, Ramamoorthy A, Kotov NA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:5110–5115. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karr JW, Akintoye H, Kaupp LJ, Szalai VA. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5478–5487. doi: 10.1021/bi047611e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karr JW, Kaupp LJ, Szalai VA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13534–13538. doi: 10.1021/ja0488028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karr JW, Szalai VA. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5006–5016. doi: 10.1021/bi702423h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shearer J, Soh P. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:710–719. doi: 10.1021/ic061236s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bunker G, Hasnain SS, Sayers D. In: X-ray Absorption Fine Structure. Hasnain SS, editor. New York: Ellis Horwood; 1991. pp. 751–770. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruotolo BT, Benesch JLP, Sandercock AM, Hyung SJ, Robinson CV. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1139–1152. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bush MF, Hall Z, Giles K, Hoyes J, Robinson CV, Ruotolo BT. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:9557–9565. doi: 10.1021/ac1022953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oh SB, Byun CJ, Yun J-H, Jo D-G, Carmeliet P, Koh J-Y, Lee J-Y. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.