Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine whether patient satisfaction and perceived quality of medical care was related to stages of activity limitations among older adults.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional study.

SETTING

Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) for calendar years 2001-2011.

PARTICIPANTS

A population-based sample (n= 42,584) of persons 65 years of age and older living in the community.

INTERVENTIONS

Not applicable.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE(S)

MCBS questions were categorized under 5 patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions: care coordination and quality, access barriers, technical skills of primary care physicians, interpersonal skills of primary care physicians, and quality of information provided by primary care physicians. Persons were classified into a stage of activity limitation (0-IV) derived from self-reported difficulty levels performing activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs).

RESULTS

Compared to older beneficiaries with no limitations at ADL Stage 0, the adjusted odds ratios (OR) (95% confidence intervals (CI)) for Stage I (mild) to Stage III (severe) for satisfaction with care coordination and quality ranged from OR = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.80-0.92) to OR = 0.79 (95% CI: 0.70-0.89). Compared to ADL Stage 0, satisfaction with access barriers ranged from OR = 0.81 (95% CI: 0.76-0.87) at Stage I (mild) to a minimum of OR = 0.67 (95% CI: 0.59-0.76) at Stage III (severe). Similarly, compared to older beneficiaries at ADL Stage 0, perceived quality of the technical skills of their primary care physician ranged from OR = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82-0.94) at Stage I (mild) to a minimum of OR = 0.81 (95% CI: 0.72-0.91) at Stage III (severe).

CONCLUSIONS

Medicare beneficiaries at higher stages of activity limitation although not necessarily the highest stage of activity limitation reported less satisfaction with medical care.

Keywords: Disabled persons, Medicare, Patient satisfaction, Elderly

INTRODUCTION

Patient satisfaction is an important indicator of quality of care1 and has been demonstrated to provide useful insights for delivering efficient care that meets patient needs.2 In some prior studies, satisfaction has been related to a single type of disabling impairment (i.e., hearing impairment, mental disability, and other chronic conditions).3-6 Other work has examined the relationship between dissatisfaction and counts of limitations of activities of daily living (ADLs). These investigators have found that patients were more likely to report dissatisfaction with the overall quality of their health care as their number of activity restrictions increased after adjusting for sociodemographic, behavioral, and system characteristics.7

However, counts of ADL or instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) limitations do not specify which activities are limited.8-10 In contrast, we sought to examine ADL and IADL limitations separately by defined stages that specify the activities older persons must be able to do without difficulty.11,12 Stages represent both the severity and types of limitations experienced and specify clinically meaningful patterns of increasing difficulty with self-care skills. By distinguishing activities older people are still able to do without difficulty from those that they find difficult, stages enhance opportunities for discourse about specific strategies for reducing disparities. No research to date has examined perceptions of care according to ADL and IADL activity limitation stages.

Older adults with disabilities have difficulty obtaining healthcare services despite the availability of efficacious treatment. As individuals advance in age, their functional capabilities decline increasing the complexity of their medical care and influencing satisfaction.13 Our goal was to examine patient satisfaction and perceived quality of medical care among community-dwelling persons 65 years of age and older with differing ADL and IADL activity limitation stages using data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), a systematic, representative sample. The objectives of the present study were 1) to describe how older Medicare beneficiaries assess satisfaction with care, access, and physician quality categorized under 5 patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions: care coordination and quality, access barriers, technical skills of primary care physicians, interpersonal skills of primary care physicians, and quality of information provided by primary care physicians; and 2) to assess whether satisfaction with care, access, and perceived physician quality were related to stages of activity limitation. We hypothesized that persons 65 years of age and older at higher stages of activity limitation would report less satisfaction with care coordination and quality, greater access barriers, and lower perceived technical skills, interpersonal skills and quality of information provided by primary care physicians compared to persons with no activity limitations.

METHODS

Study Sample from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS)

Our study is cross-sectional using MCBS questions. The study sample is derived from the MCBS, using data from calendar years 2001-2011 (n=42584). The MCBS is conducted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services through in-person beneficiary or proxy interviews.14-16 The majority of the sample responded for themselves, but 11.6% used proxies. Reasons for proxy use included hospitalization, institutionalization (temporarily), language problems, lack of mental or physical capability, absence of medical records, preference for the proxy to answer, or unavailability. Respondents are sampled from the Medicare enrollment file and the oldest old (80 and over) are oversampled to permit more detailed analyses of this sub-population.17 The sample was weighted to be representative of the fee-for-service and Health Maintenance Organization Medicare beneficiaries 65 years of age and older who were living in the community. The MCBS applies a rotating panel survey design whereby a panel is followed for 12 interviews. We used the Access to Care files at the time of their first interview. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania.

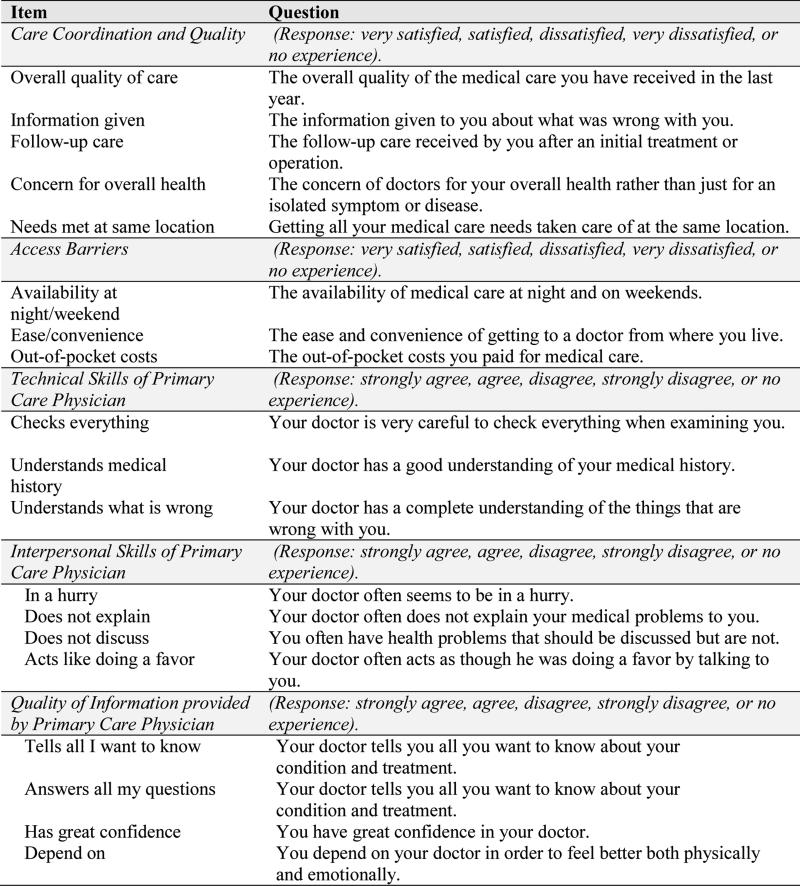

Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality

In the MCBS, a series of questions was used to measure satisfaction with care, access, and perceived physician quality. These questions were categorized under the 5 patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions listed below. Each dimension is comprised of patient or proxy answers to several questions rated either as: “very satisfied, satisfied, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied” or as: “strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree” during the patient's baseline interview. Persons reporting “no experience” with an item were counted as a missing value for only that particular item. The patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions and component questions address: 1: Care Coordination and Quality: 5 questions on overall quality of care, information given, follow-up care, concern for overall health, and needs met at same location. 2: Access Barriers: 3 questions on availability of night/weekend care, ease/convenience, and out-of-pocket costs. 3: Technical Skills of Primary Care Physician (PCP): 3 questions about checking “everything”, understanding medical history, and understanding what is wrong. 4: Interpersonal Skills of PCP: 4 questions about whether or not the PCP is in a hurry, does not explain, does not discuss, and acts like doing a favor. 5: Quality of Information provided by PCP: 4 questions about whether the PCP “tells all I want to know,” “answers all my questions,” “has my confidence,” and dependence on doctor(s) to “feel better both physically and emotionally.” Categorizing these questions under the 5 patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions is supported by factor analysis.18 Patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions 1 and 2 were available for all beneficiaries, but PCP patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions were available only for 95.1% of beneficiaries who have regular PCPs. The responses to the three to five questions under each patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimension, values ranging from 1 to 4, were used to calculate an average summated score. The average summated score corresponding to the upper quartile was considered highly satisfied for patient satisfaction dimensions and highly favorable for perceived quality dimensions. For each patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimension, the highest quartile was compared to the 3 lower quartiles similar to prior work.19 Figure 1 contains the questions about patient satisfaction with care, access, and perceived physician quality categorized by the 5 patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions.

Figure 1.

Questions about Patient Satisfaction with Care, Assess, and Perceived Physician Quality Categorized by the 5 Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality Dimensions.

Note: Data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey for calendar years 2001-2011.

Stages of Activity Limitation

Stages of activity limitation have been described in detail elsewhere.20 Briefly, stages of activity limitation were built to reflect the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. These patient-centered outcomes were derived from patient- or proxy-reported answers to simple questions about difficulties performing basic activities. The ADL and IADL stages are ordered based on the probability that people with various levels of difficulty (i.e., none, mild, moderate, severe, or complete) describe difficulty performing each activity.21 The ADLs were eating, toileting, dressing, bathing/showering, getting in or out of bed/chairs, and walking. The IADLs were using the telephone, managing money, preparing meals, doing light housework, shopping for personal items, and doing heavy housework. For each of the ADLs and IADLs, respondents are asked, “Because of a health condition, do you (or does the person you are answering for) have difficulty with...?”22,23

Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics included age (65-74, 75-84, and 85 and over24); gender; race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic African American or Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and other25); education (high school diploma or greater/less than high school diploma26); income (≤$25,000/>$25,00027); supplemental insurance type (Medicare only, Medicare and Medicaid-dual enrollee, private-supplemental, other (i.e., Champus, VA)); living arrangement (lives alone, with spouse, with children, with other relatives or non-relatives, or in a retirement community); and the presence or absence of accessibility features in the home. Health status was captured by self-reported chronic conditions and impairments.

Analysis

Our analysis proceeded in two phases. First, a descriptive analysis was applied to estimate the distribution of baseline ADL and IADL stages, sociodemographic characteristics, and self-reported health conditions and impairments. Second, logistic regression models were run to determine whether the five patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions differed by ADL and IADL stages. ADL stages (Stage 0 as reference) and IADL stages (Stage 0 as reference) were analyzed separately. For each patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimension, we performed a logistic regression using the specific dimension as the dependent variable and sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and annual income), supplemental insurance, living arrangement, home accessibility features, proxy status, self-reported health conditions and impairments as explanatory variables. Our measures of association were adjusted odd ratios with 95% confidence intervals. We tested collinearity between the variables in the final models applying criteria established by Belsley et al.28 and illustrated by Mason.29 According to this criteria, harmful collinearity is found when a condition index is larger than 20. P-values were two-sided, with statistical significance at p<0.05 in the final models. In all analyses, the complex survey design such as weight, cluster, and strata were taken into account. All statistical analyses used the survey procedures of SAS® 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

Table 1 contains the unweighted frequency and weighted percentage of the 65 years of age and older Medicare population of the 2001-2011 MCBS sample. In terms of the ADL stages of limitation, the weighted percentages were 72.3% at Stage 0, 14.7% at Stage I, 6.8% at Stage II, 5.3% at Stage III, and 0.9% at Stage IV. In terms of the IADL stages of limitation, 66.4% at Stage 0, 15.8% at Stage I, 7.1% at Stage II, 8.7% at Stage III, and 1.9% at Stage IV.

Table 1.

Stages of Activity Limitation and Beneficiary Characteristics in the Medicare population of the 2001-2011 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey Sample.

| Covariates | N | Expected N in Population (millions) | Weighted percent % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity of daily living stages | 42560 | 132.2 | |

| Stage 0 | 29236 | 95.7 | 72.3 |

| Stage I | 6859 | 19.5 | 14.7 |

| Stage II | 3389 | 8.9 | 6.8 |

| Stage III | 2580 | 7.0 | 5.3 |

| Stage IV | 496 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| Instrumental activity of daily living stages | 42550 | 132.2 | |

| Stage 0 | 26491 | 87.8 | 66.4 |

| Stage I | 7171 | 20.9 | 15.8 |

| Stage II | 3363 | 9.4 | 7.1 |

| Stage III | 4447 | 11.5 | 8.7 |

| Stage IV | 1078 | 2.6 | 1.9 |

| Age, years | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| 65-74 | 19161 | 75.8 | 57.3 |

| 75-84 | 17014 | 43.2 | 32.6 |

| ≥85 | 6409 | 13.3 | 10.1 |

| Gender | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| Female | 24160 | 74.6 | 56.4 |

| Male | 18424 | 57.7 | 43.6 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 42527 | 132.1 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 34566 | 106.8 | 80.8 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 3505 | 10.8 | 8.2 |

| Hispanic | 3163 | 10.1 | 7.6 |

| Other | 1293 | 4.5 | 3.4 |

| Proxy response | 42189 | 131.2 | |

| Self responded | 38840 | 121.9 | 92.9 |

| Proxy responded | 3349 | 9.4 | 7.1 |

| Education | 42325 | 131.6 | |

| ≥High school diploma | 30665 | 98.8 | 75.1 |

| Below high school diploma | 11660 | 32.8 | 24.9 |

| Annual income | 42224 | 131.1 | |

| ≤$25,000 | 22577 | 64.9 | 49.5 |

| >$25,000 | 19647 | 66.2 | 50.5 |

| Supplemental insurance | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| Private supplemental | 24600 | 76.7 | 58.0 |

| Medicare only | 12212 | 38.9 | 29.4 |

| Medicare and Medicaid dual enrollee | 5102 | 14.8 | 11.2 |

| Other public supplemental | 670 | 1.9 | 1.5 |

| Living arrangement | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| With spouse | 21275 | 70.6 | 53.4 |

| With children | 4287 | 12.1 | 9.1 |

| With others | 2076 | 6.6 | 5.0 |

| Alone | 11730 | 34.3 | 25.9 |

| Retirement community | 3216 | 8.7 | 6.6 |

| Having home accessibility features | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 24583 | 81.1 | 61.3 |

| Yes | 18001 | 51.3 | 38.7 |

| Alzheimer/dementia | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 41471 | 129.7 | 98.0 |

| Yes | 1113 | 2.6 | 2.0 |

| Angina pectoris/coronary artery disease | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 38419 | 120.2 | 90.9 |

| Yes | 4165 | 12.1 | 9.1 |

| Complete/partial paralysis | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 41478 | 129.1 | 97.6 |

| Yes | 1106 | 3.2 | 2.4 |

| Diabetes/high blood sugar | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 33062 | 102.5 | 77.4 |

| Yes | 9522 | 29.8 | 22.6 |

| Emphysema/asthma/COPD | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 36690 | 114.2 | 86.3 |

| Yes | 5894 | 18.2 | 13.7 |

| Hypertension | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 16881 | 53.9 | 40.7 |

| Yes | 25703 | 78.5 | 59.3 |

| Mental/psychiatric disorder | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 40626 | 126.5 | 95.6 |

| Yes | 1958 | 5.8 | 4.4 |

| Mental retardation | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 42428 | 131.8 | 99.6 |

| Yes | 156 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Myocardial infarction/heart attack | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 36980 | 116.5 | 88.1 |

| Yes | 5604 | 15.8 | 11.9 |

| Other heart conditions | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 37516 | 117.9 | 89.1 |

| Yes | 5068 | 14.4 | 10.9 |

| Parkinson's disease | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 42039 | 130.9 | 98.9 |

| Yes | 545 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Severe hearing impairment/deaf | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 39360 | 123.7 | 93.4 |

| Yes | 3224 | 8.7 | 6.6 |

| Severe vision impairment/no usable vision | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 39608 | 124.5 | 94.1 |

| Yes | 2976 | 7.8 | 5.9 |

| Stroke/brain hemorrhage | 42584 | 132.3 | |

| No | 38004 | 119.7 | 90.5 |

| Yes | 4580 | 12.6 | 9.5 |

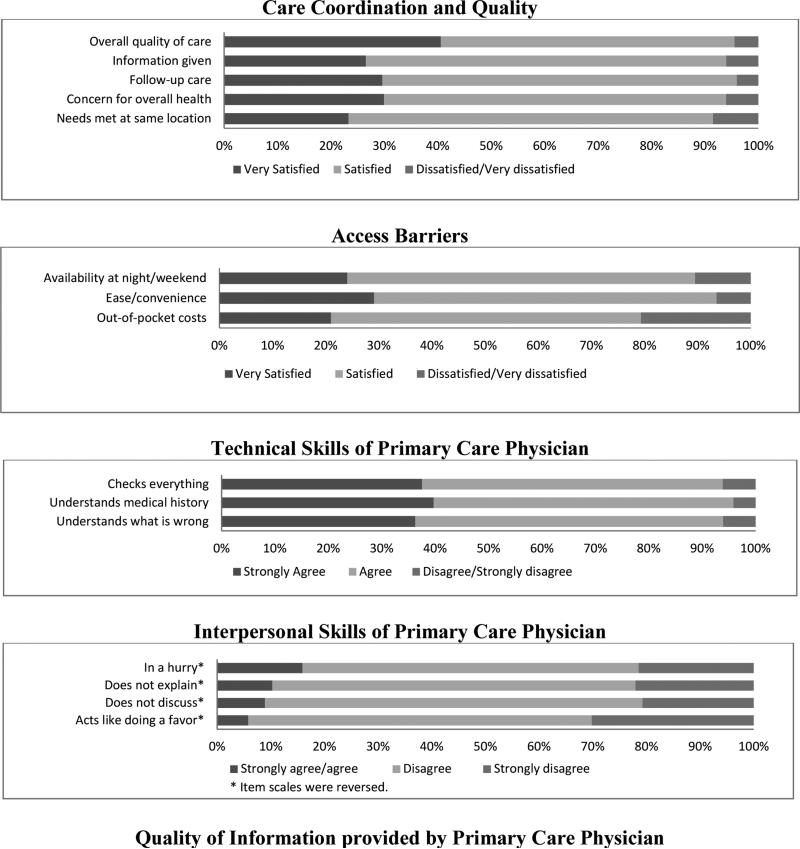

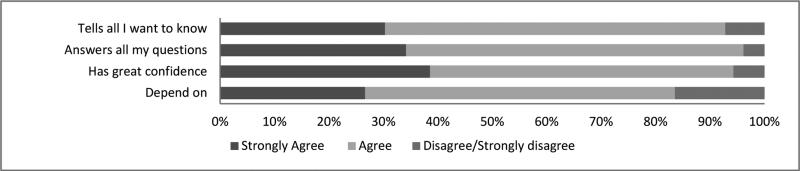

Percentage Distribution of Responses Assessing Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality of Medical Care

Overall, the proportion of older beneficiaries who were very satisfied or satisfied with care coordination and quality as well as access to care was 80% or higher (Figure 2). Approximately 95% of beneficiaries indicated strong agreement or agreement with positive statements about their primary care physician's perceived technical skills. The proportion of beneficiaries who disagreed or strongly disagreed with negative statements about their primary care physicians interpersonal skills approached 85% for most items. Approximately 85% of beneficiaries indicated agreement with positive statements about the quality of information provided by their primary care physician.

Figure 2.

Weighted Percentage Distribution of Responses Assessing Medical Care within the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey from 2001 to 2011 according to Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality Dimensions.

Note: Some percentages of dissatisfied and very dissatisfied, disagree and strongly disagree, and strongly agree and agree were combined because of the small number. Excludes beneficiaries who reported “no experience.”

Activity Limitation Stages and Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality of Medical Care

Patient satisfaction and perceived quality of medical care by ADL stages is shown in Table 2 which presents the final models from multiple logistic regression analyses for each of the five patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions. Compared to older beneficiaries with no limitations at ADL Stage 0, those at Stage I (mild) to Stage IV (complete) were less likely to report satisfaction with care coordination and quality and access to care. Overall, there was a tendency for older persons with a higher stage of activity limitation to report lower satisfaction with care and access, although not monotonically in all cases. Compared to ADL Stage 0, the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) (95% confidence intervals (CIs) for Stage I (mild) to Stage III (severe) for satisfaction with care coordination and quality ranged from OR = 0.85 (95% CI: 0.80-0.92) to OR = 0.79 (95% CI: 0.70-0.89). Compared to older beneficiaries at ADL Stage 0, those at ADL Stages IV (complete) did not have significantly lower ratings for satisfaction with care coordination and quality. However, compared to ADL Stage 0, those at Stage I (mild) to stage IV (complete) were significantly less likely to report satisfaction with access barriers ranging from OR = 0.81 (95% CI: 0.76-0.87) at Stage I (mild) to a minimum of OR = 0.67 (95% CI: 0.59-0.76) at Stage III (severe). Compared to older beneficiaries at ADL Stage 0, perceived quality of the technical skills of their primary care physician ranged from OR = 0.87 (95% CI: 0.82-0.94) at Stage I (mild) to a minimum of OR = 0.83 (95% CI: 0.65-1.05) at Stage III (severe). Compared to older beneficiaries at ADL Stage 0, those at ADL Stages IV (complete) did not have significantly lower ratings for perceived quality of the technical skills of their primary care physician. Compared to older beneficiaries at ADL Stage 0, those at ADL Stages I (mild), II (moderate), III (severe), and IV (complete) did not have significantly lower ratings for the interpersonal skills of primary care physicians or information provided by primary care physicians.

Table 2.

Activity of Daily Living Stages and the Assessment of Medical Care within the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey from 2001 to 2011 according to Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality Dimensions. Odds ratios (ORs) are adjusted for all covariates in the table with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

| Covariates | Care Coordination and Quality (n=40,677) | Access Barriers (n=40,887) | Technical Skills of Primary Care Physician (n=39,462) | Interpersonal Skills of Primary Care Physician (n=39,476) | Information Provided by Primary Care Physician (n=39,500) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity of daily living stages (reference: stage 0) | |||||

| Overall p-value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.2444 | 0.0763 |

| Stage I | 0.85 (0.8 -0.92) | 0.81 (0.76 -0.87) | 0.87 (0.82 -0.94) | 0.96 (0.89 -1.02) | 0.91 (0.85 -0.98) |

| Stage II | 0.79 (0.71 -0.87) | 0.75 (0.68 -0.84) | 0.84 (0.76 -0.92) | 0.96 (0.88 -1.05) | 0.91 (0.83 -1.01) |

| Stage III | 0.79 (0.7 -0.89) | 0.67 (0.59 -0.76) | 0.81 (0.72 -0.91) | 1.07 (0.96 -1.19) | 0.92 (0.82 -1.03) |

| Stage IV | 0.76 (0.58 -1) | 0.70 (0.53 -0.93) | 0.83 (0.65 -1.05) | 1.10 (0.87 -1.4) | 0.98 (0.77 -1.24) |

| Age, years (reference: 65-74) | |||||

| 75-84 | 0.94 (0.89 -0.99) | 1.04 (0.98 -1.09) | 0.96 (0.91 -1.01) | 0.94 (0.89 -0.99) | 0.94 (0.89 -0.99) |

| ≥85 | 0.89 (0.82 -0.96) | 1.01 (0.93 -1.09) | 0.92 (0.85 -0.99) | 0.91 (0.84 -0.98) | 0.88 (0.81 -0.95) |

| Gender (reference: female) | |||||

| Male | 1.02 (0.97 -1.08) | 1.02 (0.97 -1.08) | 0.92 (0.87 -0.97) | 0.83 (0.79 -0.87) | 0.87 (0.83 -0.92) |

| Race/Ethnicity (reference: non-Hispanic white) | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.73 (0.66 -0.82) | 0.80 (0.72 -0.9) | 1.13 (1.02 -1.25) | 0.87 (0.79 -0.97) | 1.04 (0.93 -1.15) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.62 (0.56 -0.69) | 0.61 (0.55 -0.68) | 0.81 (0.73 -0.9) | 0.78 (0.71 -0.86) | 0.78 (0.70 -0.86) |

| Other | 0.64 (0.54 -0.75) | 0.82 (0.70 -0.95) | 0.88 (0.76 -1.02) | 0.74 (0.63 -0.87) | 0.73 (0.62 -0.85) |

| Proxy response (reference: Self responded) | |||||

| Proxy responded | 0.94 (0.84 -1.04) | 0.95 (0.86 -1.06) | 1.07 (0.97 -1.19) | 0.96 (0.87 -1.06) | 0.95 (0.85 -1.05) |

| Education (reference: ≥High school diploma) | |||||

| Below high school diploma | 0.63 (0.60 -0.68) | 0.70 (0.66 -0.75) | 0.75 (0.71 -0.80) | 0.72 (0.68 -0.76) | 0.79 (0.74 -0.85) |

| Annual income (reference: ≤$25,000) | |||||

| >$25,000 | 1.63 (1.54 -1.73) | 1.70 (1.60 -1.80) | 1.32 (1.25 -1.40) | 1.35 (1.28 -1.43) | 1.31 (1.24 -1.39) |

| Supplemental insurance (reference: private supplemental) | |||||

| Medicare and Medicaid dual enrollee | 1.11 (1.00 -1.22) | 1.12 (1.01 -1.23) | 1.02 (0.93 -1.12) | 0.82 (0.74 -0.89) | 0.99 (0.90 -1.09) |

| Medicare only | 1.13 (1.07 -1.20) | 1.07 (1.01 -1.13) | 1.02 (0.97 -1.08) | 0.96 (0.91 -1.01) | 1.03 (0.97 -1.09) |

| Other public supplemental | 0.79 (0.63 -0.99) | 0.74 (0.58 -0.93) | 0.84 (0.69 -1.03) | 0.84 (0.69 -1.03) | 0.78 (0.62 -0.97) |

| Living arrangement (reference: with spouse) | |||||

| Lives alone | 0.99 (0.93 -1.06) | 1.04 (0.98 -1.11) | 1.00 (0.94 -1.07) | 0.93 (0.87 -0.99) | 0.95 (0.89 -1.02) |

| Retirement community | 1.09 (0.99 -1.20) | 1.22 (1.11 -1.35) | 1.14 (1.03 -1.25) | 1.08 (0.98 -1.18) | 1.16 (1.05 -1.28) |

| With children | 1.06 (0.96 -1.17) | 1.10 (1.00 -1.21) | 1.07 (0.98 -1.18) | 1.08 (0.99 -1.18) | 1.05 (0.95 -1.15) |

| With others | 1.10 (0.97 -1.25) | 1.12 (0.99 -1.27) | 1.15 (1.02 -1.29) | 1.11 (0.98 -1.24) | 1.13 (1.00 -1.28) |

| Having home accessibility features (reference: no) | |||||

| Having home accessibility features | 1.11 (1.05 -1.17) | 1.03 (0.97 -1.08) | 1.07 (1.01 -1.13) | 1.13 (1.07 -1.19) | 1.12 (1.06 -1.18) |

| Self-report health condition (reference: no) | |||||

| Alzheimer's/dementia | 1.02 (0.86 -1.21) | 1.03 (0.88 -1.22) | 1.03 (0.88 -1.2) | 0.96 (0.82 -1.12) | 1.08 (0.92 -1.26) |

| Angina pectoris/coronary artery disease | 1.11 (1.02 -1.21) | 1.01 (0.93 -1.10) | 1.10 (1.01 -1.20) | 1.12 (1.03 -1.22) | 1.19 (1.09 -1.29) |

| Complete/partial paralysis | 1.21 (1.04 -1.41) | 1.06 (0.90 -1.25) | 1.17 (1.00 -1.36) | 1.16 (1.00 -1.35) | 1.12 (0.96 -1.31) |

| Diabetes/high blood sugar | 1.07 (1.01 -1.14) | 1.00 (0.94 -1.06) | 1.16 (1.09 -1.23) | 1.05 (0.99 -1.11) | 1.13 (1.06 -1.20) |

| Emphysema/asthma/ COPD | 1.10 (1.02 -1.18) | 0.90 (0.83 -0.97) | 1.09 (1.02 -1.17) | 1.13 (1.05 -1.21) | 1.15 (1.07 -1.24) |

| Hypertension | 1.02 (0.97 -1.08) | 0.93 (0.88 -0.98) | 1.02 (0.97 -1.07) | 0.99 (0.94 -1.04) | 1.08 (1.02 -1.14) |

| Mental/psychiatric disorder | 0.96 (0.85 -1.08) | 0.93 (0.82 -1.05) | 0.91 (0.81 -1.03) | 0.94 (0.83 -1.05) | 0.91 (0.80 -1.03) |

| Mental retardation | 1.05 (0.70 -1.56) | 1.07 (0.71 -1.61) | 1.05 (0.70 -1.56) | 1.04 (0.70 -1.54) | 1.07 (0.73 -1.59) |

| Myocardial infarction/heart attack | 1.07 (0.99 -1.16) | 0.98 (0.91 -1.06) | 1.04 (0.97 -1.13) | 1.01 (0.94 -1.09) | 1.01 (0.94 -1.09) |

| Other heart conditions | 0.98 (0.91 -1.06) | 0.95 (0.88 -1.03) | 1.00 (0.92 -1.08) | 1.00 (0.93 -1.07) | 0.99 (0.92 -1.07) |

| Parkinson's disease | 0.76 (0.60 -0.96) | 0.89 (0.71 -1.12) | 0.86 (0.69 -1.07) | 0.81 (0.66 -1.00) | 0.90 (0.72 -1.12) |

| Severe hearing impairment /deaf | 0.78 (0.70 -0.87) | 0.77 (0.69 -0.85) | 0.89 (0.81 -0.99) | 0.99 (0.90 -1.09) | 0.89 (0.81 -0.99) |

| Severe vision impairment /no usable vision | 0.82 (0.74 -0.92) | 0.82 (0.74 -0.91) | 0.91 (0.82 -1.01) | 0.96 (0.87 -1.06) | 0.98 (0.88 -1.08) |

| Stroke/brain hemorrhage | 1.03 (0.95 -1.12) | 1.01 (0.93 -1.10) | 1.10 (1.01 -1.19) | 1.09 (1.01 -1.18) | 1.09 (1.00 -1.19) |

Notes:

1. Reference category of each variable is noted in parentheses. N denotes number of observations used in the analysis. COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

2. For the first and second comparators, 857 and 633, respectively, participants reported no experiences in all items so they were excluded. Among the eligible participants, 676 (1.6%) and 686 (1.6%) had missing values in all items for the first or second comparator respectively. For the last three comparators, 1872 participants were first excluded because they did not have a primary care physician. Then 195, 186, and 170 were excluded because they did not have experiences in all the items for these three comparators respectively. Further, 693 (1.7%), 687 (1.7%), and 680 (1.7%) were excluded due to missing values.

Instrumental Activity Limitation Stages and Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality of Medical Care

Patient satisfaction and perceived quality of medical care by instrumental activity of daily living stages is shown in Table 3. The results for the instrumental activity of daily living stages parallel the results for the activity of daily living stages with the exception of the perceived quality of information provided by physicians. Compared to beneficiaries with no limitations at IADL Stage 0, ratings for the perceived quality of information provided by their physicians ranged from OR = 0.90 (95% CI: 0.84-0.97) at IADL Stage I (mild) to a minimum of OR = 0.82 (95% CI: 0.75-0.90) at IADL Stage III (severe).

Table 3.

Instrumental Activity of Daily Living Stages and the Assessment of Medical Care within the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey from 2001 to 2011 according to Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality Dimensions. Odds ratios (ORs) are adjusted for all covariates in the table with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

| Covariates | Care Coordination and Quality (n=4,0667) | Access Barriers (n=4,0876) | Technical Skills of Primary Care Physician (n=3,9452) | Interpersonal Skills of Primary Care Physician (n=3,9466) | Information Provided by Primary Care Physician (n=3,9490) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental activity of daily living stages (reference: stage 0) | |||||

| Overall p-value | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.2379 | <.0001 |

| Stage I | 0.83 (0.77 -0.89) | 0.80 (0.74 -0.86) | 0.92 (0.86 -0.98) | 0.94 (0.88 -1.00) | 0.90 (0.84 -0.97) |

| Stage II | 0.73 (0.66 -0.81) | 0.69 (0.62 -0.76) | 0.80 (0.72 -0.88) | 0.94 (0.85 -1.03) | 0.87 (0.78 -0.96) |

| Stage III | 0.74 (0.67 -0.82) | 0.65 (0.59 -0.72) | 0.82 (0.74 -0.90) | 0.96 (0.88 -1.05) | 0.82 (0.75 -0.90) |

| Stage IV | 0.89 (0.73 -1.08) | 0.70 (0.58 -0.85) | 0.92 (0.77 -1.11) | 1.04 (0.88 -1.24) | 1.05 (0.88 -1.26) |

| Age, years (reference: 65-74) | |||||

| 75-84 | 0.95 (0.90 -1.00) | 1.05 (0.99 -1.10) | 0.96 (0.91 -1.01) | 0.94 (0.89 -0.99) | 0.94 (0.89 -0.99) |

| ≥85 | 0.90 (0.83 -0.97) | 1.03 (0.95 -1.11) | 0.92 (0.85 -0.99) | 0.91 (0.85 -0.98) | 0.88 (0.82 -0.96) |

| Gender (reference: female) | |||||

| Male | 1.01 (0.95 -1.06) | 1.00 (0.95 -1.06) | 0.91 (0.87 -0.97) | 0.82 (0.78 -0.86) | 0.87 (0.82 -0.92) |

| Race/Ethnicity (reference: non-Hispanic white) | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.73 (0.66 -0.82) | 0.81 (0.72 -0.90) | 1.13 (1.02 -1.25) | 0.88 (0.79 -0.97) | 1.04 (0.93 -1.15) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.62 (0.56 -0.69) | 0.61 (0.55 -0.68) | 0.81 (0.73 -0.89) | 0.78 (0.71 -0.86) | 0.77 (0.70 -0.86) |

| Other | 0.64 (0.54 -0.76) | 0.82 (0.71 -0.96) | 0.89 (0.76 -1.03) | 0.74 (0.63 -0.86) | 0.73 (0.62 -0.86) |

| Proxy response (reference: Self responded) | |||||

| Proxy responded | 0.94 (0.84 -1.04) | 0.98 (0.88 -1.09) | 1.07 (0.97 -1.19) | 0.96 (0.87 -1.06) | 0.95 (0.85 -1.06) |

| Education (reference: ≥High school diploma) | |||||

| Below high school diploma | 0.64 (0.60 -0.68) | 0.71 (0.66 -0.76) | 0.75 (0.71 -0.80) | 0.72 (0.68 -0.77) | 0.80 (0.75 -0.85) |

| Annual income (reference: ≤$25,000) | |||||

| >$25,000 | 1.63 (1.53 -1.72) | 1.69 (1.59 -1.79) | 1.32 (1.25 -1.4) | 1.34 (1.27 -1.42) | 1.31 (1.23 -1.39) |

| Supplemental insurance (reference: private supplemental) | |||||

| Medicare and Medicaid dual enrollee | 1.12 (1.01 -1.23) | 1.13 (1.03 -1.25) | 1.03 (0.94 -1.13) | 0.82 (0.75 -0.90) | 1.00 (0.91 -1.1) |

| Medicare only | 1.13 (1.07 -1.20) | 1.07 (1.01 -1.13) | 1.02 (0.97 -1.08) | 0.96 (0.91 -1.01) | 1.03 (0.97 -1.09) |

| Other public supplemental | 0.79 (0.63 -0.99) | 0.74 (0.58 -0.93) | 0.84 (0.69 -1.03) | 0.84 (0.69 -1.02) | 0.78 (0.62 -0.97) |

| Living arrangement (reference: with spouse) | |||||

| Lives alone | 0.99 (0.93 -1.05) | 1.03 (0.97 -1.1) | 1.00 (0.94 -1.07) | 0.93 (0.87 -0.99) | 0.95 (0.89 -1.01) |

| Retirement community | 1.09 (0.99 -1.20) | 1.22 (1.11 -1.35) | 1.14 (1.03 -1.25) | 1.08 (0.98 -1.18) | 1.16 (1.05 -1.28) |

| With children | 1.06 (0.96 -1.17) | 1.10 (1.00 -1.21) | 1.07 (0.98 -1.18) | 1.08 (0.99 -1.18) | 1.05 (0.95 -1.15) |

| With others | 1.10 (0.97 -1.25) | 1.12 (0.98 -1.26) | 1.14 (1.01 -1.29) | 1.11 (0.99 -1.25) | 1.13 (1.00 -1.27) |

| Having home accessibility features (reference: no) | |||||

| Having home accessibility features | 1.11 (1.05 -1.17) | 1.03 (0.97 -1.08) | 1.07 (1.01 -1.12) | 1.13 (1.08 -1.19) | 1.12 (1.06 -1.18) |

| Self-report health condition (reference: no) | |||||

| Alzheimer's/dementia | 1.02 (0.86 -1.21) | 1.09 (0.92 -1.29) | 1.02 (0.87 -1.20) | 0.96 (0.82 -1.12) | 1.07 (0.90 -1.26) |

| Angina pectoris/coronary artery disease | 1.11 (1.02 -1.21) | 1.02 (0.93 -1.11) | 1.10 (1.01 -1.19) | 1.12 (1.04 -1.22) | 1.19 (1.09 -1.29) |

| Complete/partial paralysis | 1.20 (1.03 -1.4) | 1.06 (0.90 -1.24) | 1.16 (0.99 -1.35) | 1.18 (1.02 -1.37) | 1.12 (0.96 -1.31) |

| Diabetes/high blood sugar | 1.07 (1.01 -1.14) | 1.00 (0.94 -1.06) | 1.16 (1.09 -1.23) | 1.05 (0.99 -1.12) | 1.13 (1.06 -1.2) |

| Emphysema/asthma/ COPD | 1.11 (1.03 -1.19) | 0.90 (0.84 -0.97) | 1.09 (1.02 -1.17) | 1.14 (1.06 -1.22) | 1.16 (1.08 -1.24) |

| Hypertension | 1.02 (0.97 -1.08) | 0.93 (0.88 -0.98) | 1.02 (0.96 -1.07) | 0.99 (0.94 -1.04) | 1.08 (1.02 -1.14) |

| Mental/psychiatric disorder | 0.97 (0.85 -1.09) | 0.94 (0.83 -1.06) | 0.92 (0.81 -1.03) | 0.94 (0.84 -1.06) | 0.92 (0.81 -1.04) |

| Mental retardation | 1.06 (0.71 -1.58) | 1.12 (0.74 -1.69) | 1.05 (0.71 -1.56) | 1.04 (0.70 -1.54) | 1.08 (0.73 -1.60) |

| Myocardial infarction/heart attack | 1.08 (1.00 -1.16) | 0.99 (0.91 -1.07) | 1.05 (0.97 -1.13) | 1.02 (0.94 -1.09) | 1.02 (0.94 -1.10) |

| Other heart conditions | 0.99 (0.91 -1.07) | 0.96 (0.89 -1.03) | 1.00 (0.93 -1.08) | 1.00 (0.93 -1.08) | 0.99 (0.92 -1.07) |

| Parkinson's disease | 0.75 (0.60 -0.95) | 0.89 (0.71 -1.12) | 0.85 (0.69 -1.06) | 0.82 (0.67 -1.01) | 0.90 (0.72 -1.13) |

| Severe hearing impairment /deaf | 0.81 (0.73 -0.90) | 0.82 (0.74 -0.91) | 0.92 (0.83 -1.01) | 1.00 (0.91 -1.10) | 0.92 (0.83 -1.02) |

| Severe vision impairment /no usable vision | 0.83 (0.74 -0.93) | 0.84 (0.76 -0.94) | 0.92 (0.83 -1.01) | 0.96 (0.87 -1.06) | 0.99 (0.89 -1.09) |

| Stroke/brain hemorrhage | 1.04 (0.95 -1.13) | 1.02 (0.94 -1.11) | 1.09 (1.01 -1.19) | 1.10 (1.01 -1.19) | 1.09 (1.01 -1.19) |

Notes:

1. Reference category of each variable is noted in parentheses. N denotes number of observations used in the analysis. COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

2. In addition to the missing values in the 5 comparators, a small number of participants (<10) were further excluded because of missing IADL stages.

Other Factors Associated with Patient Satisfaction and Perceived Quality of Medical Care

In Tables 2 and 3, age, ethnicity, education, and income were significantly associated with patient satisfaction and perceived quality of medical care. Notably, persons with severe vision impairment/no usable vision and persons with severe hearing impairment/deaf were less likely to report satisfaction with care coordination and quality and access to care (all p-values<.001). As per the criteria established by Belsley et al.28 there were no concerns regarding collinearity among the variables in the final model. The largest condition index from the collinearity matrix was 3.2.

DISCUSSION

Most Medicare beneficiaries 65 years of age and older were satisfied with care and access to medical services. Overall, beneficiaries expressed favorable views of physician quality in terms of perceived technical and interpersonal skills as well as information-giving. However, our findings indicate dissatisfaction relative to care coordination and quality and access barriers may be associated with higher stages of activity limitation. Specifically, compared to beneficiaries without disability, beneficiaries at higher stages of activity limitation although not necessarily the highest stage of activity limitation were less likely to report satisfaction with medical care.

The first aim of our study was to describe how MCBS beneficiaries assess satisfaction with care, access, and physician quality categorized under the 5 patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions. Across the 5 patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions, more than 80% of beneficiaries reported being very satisfied or satisfied. Over 90% of the beneficiaries surveyed reported being very satisfied or satisfied with care coordination and quality as well as the technical skills of primary care physicians.

The second aim of our study was to assess whether satisfaction with care, access, and perceived physician quality was related to stages of activity limitation. We found that persons at a higher stage of activity limitation were more likely to be less satisfied with care coordination and quality as well as access even after controlling for a broad array of factors. While one might posit that persons with disability are likely to be more dissatisfied because they have many characteristics associated with dissatisfaction (i.e., poverty) our results that the relationship persists after holding such factors constant suggest that there may be inherent elements that predispose persons with disability to be dissatisfied with medical care. Potentially influential factors include limited transportation, structural barriers (i.e., no ramps to get to the practice and inaccessible exam tables) and negative attitudes and perceptions towards persons with disabilities held by healthcare providers and staff. Further investigation of these underlying components is an important area of further inquiry.

Our results deserve attention because this was the first examination of whether patient satisfaction and perceived quality of medical care was related to activity limitation stages. Our findings add to a growing body of knowledge suggesting that as the burden of disability increases, dissatisfaction with medical care may substantially increase. In contrast to prior work, we assess ADLs and IADLs in terms of stages that represent both the severity and types of limitations experienced. These stages distinguish activities people are still able to do without difficulty from those that they find difficult enhancing discourse for the development of effective strategies for care provision. We also assess specific types of disability, vision and hearing impairment, in relation to dimensions of satisfaction thus expanding our knowledge of who may be most dissatisfied.

Knowledge of patients’ stages of activity limitation can alert clinicians to some of the specific quality and access problems they are likely to experience. While at ADL Stage I (mild) people are guaranteed to be able to eat, toilet, dress themselves and bath or shower without difficulties they experience difficulties getting in and out of chairs and walking. These mobility limitations mark a potential need for physical accessibility accommodations. By ADL Stage II (moderate) people are having difficulty dressing and/or bathing bringing vulnerability to further quality decline, if patients are examined without dis-robing. Patient satisfaction and accessibility concerns did not appear to increase further at the highest stages of activity limitation. Since at ADL Stage IV (complete) information is often provided by proxy interviews, the case assessment is that experienced by the care giver or proxy rather than by the patient. Responses provided by proxy interviews may not reflect how the sampled person themselves would have responded. As people begin to have difficulty with tasks such as shopping which typically requires mobility in the community they will logically have difficulty accessing ambulatory services. To our knowledge this is the first time an association has been identified between IADL limitations and perceptions of healthcare quality and access. Of note, the dimensions of care coordination and quality and access to services were the most sensitive to activity limitation stage thus reflecting their fundamental role in determining whether or not care can be obtained.

Consistent with prior investigations, ethnicity, education, and income were strongly related to satisfaction with care and perceptions of physician quality.19 In addition, the presence of severe vision impairment or severe hearing impairment was strongly associated with lower satisfaction with care coordination and quality as well as lower satisfaction with access. These findings are consistent with studies demonstrating the gaps in care experienced by persons with severe vision or hearing impairments and underscores the importance of devising strategies to communicate effectively with all patients.30-33

The reduction of gaps between the most and least vulnerable groups of older people is a critical priority noted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Institutes of Health.34 Our findings substantiate an expanding body of knowledge indicating that among older persons, those with disability evaluate services differently than those without disability. As more is learned about factors influencing satisfaction in persons with disability, we may be able to more accurately develop strategies to improve satisfaction and health outcomes. These findings suggest thatproviders should be aware of older patient's activity limitation stage and interventions may need to be developed for patients at higher activity limitation stages in order to improve patient satisfaction. Drawing on patient participatory research, strategies may be employed that incorporate patient perceptions and evaluations of quality care provision. Such approaches may ultimately increase older patient's satisfaction, the quality of care provision, patient outcomes, and system effectiveness.

Study Limitations

Several study limitations should be considered. First, while the MCBS sample is intended to be representative of the entire Medicare population, our analyses did not include beneficiaries less than 65 years of age. Second, we employed self-reports which have been shown to have varying degrees of reliability due to factors such as recall and social desirability bias. Third, we realize that proxy-related answers to self-perception questions may differ from answers provided by the sampled beneficiaries themselves. We included information from proxies since previous findings suggest that including proxy responses may reduce bias.35 Fourth, we are unable to discern the temporal relationship between activity limitation stages and satisfaction due to the cross-sectional nature of this study. However, prior evidence demonstrates a temporal relationship between impaired functioning and the satisfaction with care7 and our findings support this framework. Finally, even with confidence in our assessments, misspecification of the model is still a possibility, such as when important variables have not been included. We attempted to take care in adjusting our estimates of association for all potentially influential characteristics. Nevertheless, other important factors such as expectations, past experiences, and general outlook may be important in understanding satisfaction but were unmeasured and thus were not incorporated into this analysis. Evidence indicates that persons who have less satisfaction with their lives in general report lower satisfaction with medical care. In controlling for perceived health we may have been able to account for this potential bias. However, we cannot negate the possibility that differences in general life satisfaction may have contributed to our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Across the patient satisfaction and perceived quality dimensions (care coordination and quality, access barriers, technical skills of primary care providers, interpersonal skills of primary care providers, and information provided by primary care physicians) most MCBS beneficiaries reported being very satisfied or satisfied with care. Medicare beneficiaries at higher stages of activity limitation, although not necessarily the highest stage of activity limitation, in comparison with beneficiaries at the lowest stage of activity limitation reported less satisfaction with medical care across the five dimensions. Knowledge of a patient's ADL and IADL stage can provide insight about the specific types of accessibility needs and quality pitfalls they are likely to experience allowing for the tailoring of interventions to patient's needs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute PCORI Project Program Award AD-12-11-4567 and by the National Institutes of Health (R01AG040105 and R01HD074756). Dr. Bogner was supported by an American Heart Association Award #13GRNT17000021, a National Institute of Mental Health R21 MH094940, and a National Institute of Mental Health R34 MH085880.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADLs

activities of daily living

- IADLs

instrumental activities of daily living

- MCBS

Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey

- PCP

Primary Care Physician

- ORs

odds ratios

- CIs

confidence intervals

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of Interest: The authors have no financial or any other kind of conflicts of interest to declare.

Suppliers

SAS version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, 100 SAS Campus Dr, Cary, NC 27513.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988 Sep 23-30;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams B. Patient satisfaction: a valid concept? Soc Sci Med. 1994 Feb;38(4):509–516. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, Soukup J, O'Day B. Physical and sensory functioning over time and satisfaction with care: the implications of getting better or getting worse. Health Serv Res. 2004 Dec;39(6 Pt 1):1635–1651. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenbach ML. Access and satisfaction within the disabled Medicare population. Health Care Financ Rev. 1995;17(2):147–167. Winter. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett DD, Koul R, Coppola NM. Satisfaction with health care among people with hearing impairment: a survey of Medicare beneficiaries. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(1):39–48. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.777803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, Soukup J, O'Day B. Quality dimensions that most concern people with physical and sensory disabilities. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Sep 22;163(17):2085–2092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jha A, Patrick DL, MacLehose RF, Doctor JN, Chan L. Dissatisfaction with medical services among Medicare beneficiaries with disabilities. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2002 Oct;83(10):1335–1341. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Projected Medicare Expenditures under an Illustrative Scenario with Alternative Payment Updates to Medicare Providers. Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS). Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS); 2011. [October 10, 2012]. at https://www.cms.gov/ReportsTrustFunds/downloads/2011TRAlternativeScenario.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culler SD, Parchman ML, Przybylski M. Factors related to potentially preventable hospitalizations among the elderly. Med Care. 1998 Jun;36(6):804–817. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199806000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lubitz J, Cai L, Kramarow E, Lentzner H. Health, life expectancy, and health care spending among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003 Sep 11;349(11):1048–1055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [January 15, 2010];Dynamic Tools to Measure Health from the Patient Perspective. (at http://www.nihpromis.org/default.aspx)

- 12.Stineman MG, Streim JE, Pan Q, Kurichi JE, Schussler-Florenza Rose SM, Xie D. Establishing an Approach to Activity of Daily Living and Instrumental Activity of Daily Living Staging in the United States Adult Community-Dwelling Medicare Population. PM & R. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Council on Disability . The current state of health care for people with disabilities. Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14. [July 10, 2014];Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) 2005 https://www.cms.gov/MCBS/

- 15. [September 21, 2011];Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) Access to Care Introduction. 2005 2010, at https://www.cms.gov/MCBS/

- 16. [November 20, 2011];Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual, Chapter 1, Part 4 (Sections 200 – 310.1) Coverage Determinations (Rev. 135, 09-22-11) 2011 at https://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_part4.pdf)

- 17.Health and Health Care of the Medicare Population. Technical Documentation for the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey- Appendix A. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohr KN, Schroeder SA. A strategy for quality assurance in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 1990 Mar 8;322(10):707–712. doi: 10.1056/nejm199003083221031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y, Kasper JD. Assessment of medical care by elderly people: general satisfaction and physician quality. Health Serv Res. 1998 Feb;32(6):741–758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stineman MG, Henry-Sanchez JT, Kurichi JE, et al. Staging activity limitation and participation restriction in elderly community-dwelling persons according to difficulties in self-care and domestic life functioning. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. 2012 Feb;91(2):126–140. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318241200d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stineman MG, Streim JE, Pan Q, Kurichi JE, Schussler-Fiorenza Rose SM, Xie D. Activity Limitation Stages empirically derived for Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental ADL in the U.S. Adult community-dwelling Medicare population. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. 2014 Nov;6(11):976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.05.001. quiz 987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stineman MG, Xie D, Pan Q, Kurichi JE, Saliba D, Streim J. Activity of daily living staging, chronic health conditions, and perceived lack of home accessibility features for elderly people living in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011 Mar;59(3):454–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoover DR, Crystal S, Kumar R, Sambamoorthi U, Cantor JC. Medical expenditures during the last year of life: findings from the 1992-1996 Medicare current beneficiary survey. Health Serv Res. 2002 Dec;37(6):1625–1642. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craig BM, Kreling DH, Mott DA. Do seniors get the medicines prescribed for them? Evidence from the 1996-1999 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003 May-Jun;22(3):175–182. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Malley AS, Forrest CB, Feng S, Mandelblatt J. Disparities despite coverage: gaps in colorectal cancer screening among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Oct 10;165(18):2129–2135. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.18.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan L, Ciol MA, Shumway-Cook A, et al. A longitudinal evaluation of persons with disabilities: does a longitudinal definition help define who receives necessary care? Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2008 Jun;89(6):1023–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belsley D, Kuh E, Welsch R. Regression Diagnostics. John Wiley; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mason G. Coping with collinearity. Can J Program Eval. 1987;2:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Hearn A. Deaf women's experiences and satisfaction with prenatal care: a comparative study. Fam Med. 2006 Nov-Dec;38(10):712–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iezzoni LI, Davis RB, Soukup J, O'Day B. Satisfaction with quality and access to health care among people with disabling conditions. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002 Oct;14(5):369–381. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/14.5.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iezzoni LI, O'Day BL, Killeen M, Harker H. Communicating about health care: observations from persons who are deaf or hard of hearing. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Mar 2;140(5):356–362. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harmer L. Health care delivery and deaf people: practice, problems, and recommendations for change. Journal of deaf studies and deaf education. 1999;4(2):73–110. doi: 10.1093/deafed/4.2.73. Spring. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. [September 13, 2011];Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011 Jan 14; 2011. (at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6001.pdf.)

- 35.Stineman MG, Ross RN, Maislin G. Functional status measures for integrating medical and social care. Int J Integr Care. 2005;5:e07. doi: 10.5334/ijic.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]