Abstract

Background

Low-trauma, osteoporotic fractures among older men are associated with a significant increase in morbidity and mortality. Despite effective therapies for osteoporosis, several studies have demonstrated that management and treatment after a low trauma fracture remains inadequate, especially among men. Fracture Liaison Services have been shown to significantly improve osteoporosis evaluation and treatment. However, such programs may be less feasible and accessible in rural areas, with limited availability of specialty services.

Objective

To evaluate a centralized, electronic consult (E-consult) program serving multiple Veterans Administration Medical Centers, including the geographic scope, accessibility to rural patients, and impact on osteoporosis evaluation and treatment.

Method

The E-consult program identified Veterans with potential osteoporotic fractures from inpatient and outpatient encounter data, based on ICD9 diagnosis codes (800–829) from the central data warehouse. The medical record of an eligible patient was reviewed by a bone health specialist, and an E-consult note was sent to the patient’s primary care provider that specified guideline-based recommendations for further evaluation and management. A bone health nurse liaison then coordinated the ordering and follow-up of laboratory and bone density assessment, osteoporosis education (e.g. medication administration and side effects, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, falls prevention, and exercise), and adherence follow-up via telephone.

Patients were identified as living in a rural area if their ZIP code was not in a US Census Bureau-defined urban area (i.e. population density greater than 1000-persons per square mile [approximately 386-persons per square kilometer]).

Results

From October 2013 through September 2014, 2775 fractures were identified by a fracture-related ICD9 code. After exclusion of those age less than 50 years and high-trauma fractures, 321 E-consults were completed. Of those, 171 (53.3%) were for patients residing in a rural or highly rural area. The E-consult program saved a total of 11,917 miles (19,178 kilometers) of travel. For rural patients, bisphosphonates were recommended 51 times, with 33 (64.7%) ordered, and bone density assessments were recommended 109 times with 79 (72.5%) ordered. A nurse liaison significantly improved bisphosphonate ordering (from 39.7 to 75.8%) and BMD testing completion rates (from 37.1 to 63.0%), for both rural and urban patients (P < 0.01).

Conclusion

A centralized, E-consult program can effectively and efficiently provide specialty bone health services to patients residing in rural areas. The program was able to save a substantial number of travel miles and increase the rates of evaluation and treatment for osteoporosis.

Keywords: E-consult, fracture, fracture liaison services, osteoporosis, prevention, Veterans Administration

Introduction

Low-trauma, osteoporotic fractures among older men are associated with a twofold increase in mortality; in particular, hip fractures are associated with a 1-year mortality of 30%[1–3]. Low-trauma fractures are also associated with decreased mobility, increased pain and functional limitations, increased risk of institutionalization, as well as an increased risk for subsequent fractures[4–10]. Treatment for osteoporosis has been shown to greatly reduce the risk of subsequent fractures and significantly reduce the risk in mortality[11–13].

Despite effective therapies for osteoporosis, several studies have demonstrated that management and treatment after a low trauma fracture remains inadequate, especially among men[14–17]. In 2010, the Veterans Administration’s (VA) Office of the Inspector General reviewed osteoporosis care among Veterans with low trauma fracture, and found that only 24% received appropriate care[18]. System-wide quality improvement interventions were advocated including provider education, patient education, and improved surveillance components.

While Fracture Liaison Services have been shown to significantly improve osteoporosis treatment[19–21], they frequently rely on local availability of a specialty team with expertise in metabolic bone disease. Such a service may be less feasible for medical centers, such as the VA Health Administration, who care for a large number of patients living in rural areas. Substantial disparities in the availability and quality of medical care have been described for rural patients, who are on average 5 years older than urban patients and therefore have a higher burden of age-related chronic diseases such as osteoporosis[22, 23]. Therefore, comparing the reach and impact of models such as fracture liaison services in rural patients is an important goal.

We previously have described our post-fracture electronic consult (E-consult) program at a single, centralized Veterans Administration Medical Center (VAMC), and the program’s effects on osteoporosis screening and treatment rates[24]. In the current study, we sought to determine the geographic scope of the E-consult program and its impact on rural patients in this region, wherein over 43 percent of the Veterans live in rural or highly rural areas.

Methods

The Osteoporosis E-consult program has been described previously[24,25]. Patients with recent fracture were identified by a central data warehouse report using fracture-related International Classification of Disease (ICD9) codes (specifically 733.93 – 733.95; 767.3; 800 – 829; V54.13). The program coordinating staff then complete an electronic medical record screening at the central coordinating VAMC. Eligibility for the E-consult program included patients over age 50 years, who had sustained a low trauma fracture within the last 12 months, and who had a primary care provider within the VAMC. Patients were excluded for fractures not considered osteoporotic (for example, facial, skull, or digital fractures) and for fractures that occurred more than 10 years prior.. Patients with an active prescription for a bisphosphonate, a recent bone mineral density (BMD) testing, or an estimated life expectancy of 1 year or less were also excluded. Patients with medical record documentation noting that the patient had been offered but s/he had declined osteoporosis screening or therapy were not included. Also, patients who had died after the index fracture but prior to medical record screening by the E-consult coordinating staff, were not included.

After screening by the E-consult coordinating staff, patients were referred to a metabolic bone specialist, a physician with training in endocrinology and/or geriatric medicine, for chart review. Medical chart review included identification of other clinical risk factors for osteoporosis, for example, low body mass index, hyperparathyroidism, or rheumatoid arthritis. The physician also reviewed prior laboratory results, such as serum chemistries and vitamin D levels)and prior medical treatments, such as corticosteroid use or androgen-deprivation therapy. The physician then provided a consult note with recommendations regarding osteoporosis screening (for example, bone density assessment) and possible osteoporosis treatment based on practice guidelines from the National Osteoporosis Foundation and the Veterans Administration[18,26]. The consult note was sent to the patient’s primary care provider via the electronic medical record for review.

Starting in Oct 2013, a bone health nurse liaison, located at the central VAMC, coordinated the evaluation and management plans for PCP-reviewed recommendations, including ordering and follow-up of laboratory and bone density assessment, osteoporosis education (e.g. medication administration and side effects, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, falls prevention, and exercise), and adherence follow-up via telephone. Initially, the nurse liaison only served clinics associated with the central VAMC, but then starting in Jan 2014 expanded to include the additional 2 nearest VAMCs, while the remaining 2 VAMCs did not receive nurse services. Thus, the effect of the nurse liaison service could be assessed. Nurse liaison services were provided to both urban and rural patients at the associated VAMCs.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were identified as living in a rural area if their ZIP code was not in a US Census Bureau-defined urban area, population density greater than 1000-persons per square mile (approximately 386-persons per square kilometer). Baseline characteristics for the patients are described using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means with standard deviations for continuous variables. To compare rural and urban subjects, Student’s t test was used for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Expected numbers were based on VA regional enrollment data from FY13 and the relative proportion of rural/highly rural enrollees. Statistical significance was assessed for p < 0.05. Maps were based on the ZIP code tabulation areas obtained from the US Census Bureau. Total travel distance saved was based on mileage from Veterans home address to nearest VA primary care clinic. Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Durham VAMC (#01653).

Results

Study Population

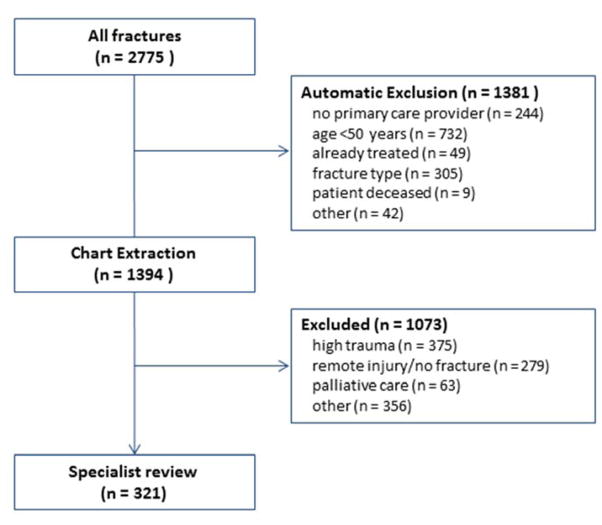

From October 2013 to September 2014, there were 2775 fractures identified by a fracture-related ICD9 code (Figure 1). Of these, 1381 were automatically excluded from E-consult due to ineligibility. The most common reason was because the Veteran was less than age 50 years. An additional 1073 were excluded during the chart extraction phase. The most common reason for exclusion during chart extraction was because the fracture occurred due to high trauma. Therefore, 321 unique individuals with fractures were subsequently reviewed by a metabolic bone specialist, of which 171 occurred in rural Veterans.

Figure 1.

Diagram of E-consult referral process

Baseline patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Veterans were predominantly male (94.7%) with a mean age of 70.5 +/− 10.6 years. Common medical comorbidities included diabetes mellitus and chronic lung disease. The most common fracture sites were of the lower leg (24.7%) and of the hip/pelvis (21.9%). Demographics, medical comorbidities, or fracture site, were not significantly different between the rural and urban Veterans.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Veterans with an E-consult

| Rural N = 171 |

Urban N = 150 |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

|

| |||

| Age, mean ± SD | 70.7 ± 10.8 | 70.3 ± 10.4 | 0.77 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 27.2 ± 6.0 | 28.1 ± 6.4 | 0.25 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.30 | ||

| Male | 164 (95.9) | 140 (93.3) | |

| Female | 7 (4.1) | 10 (6.7) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.48 | ||

| White | 125 (73.1) | 100 (66.7) | |

| Black | 34 (19.9) | 41 (27.3) | |

| Other | 4 (2.3) | 3 (2.0) | |

| Unknown | 8 (4.7) | 6 (4.0) | |

|

| |||

| Comorbidities | |||

|

| |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 61 (35.7) | 57 (38.0) | 0.67 |

| Chronic lung disease | 42 (24.6) | 36 (24.0) | 0.91 |

| Neurologic disease | 30 (17.5) | 20 (13.3) | 0.30 |

| Alcohol abuse | 29 (17.0) | 31 (20.7) | 0.29 |

| Prostate Cancer | 11 (6.4) | 14 (9.3) | 0.33 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 (2.3) | 2 (1.3) | 0.69 |

| Anticonvulsant use | 40 (23.4) | 32 (21.3) | 0.63 |

| Corticosteroid use | 3 (1.8) | 2 (1.3) | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| Fracture site, n | |||

|

| |||

| Vertebral | 17 | 13 | 0.29 |

| Hip/pelvis | 30 | 41 | |

| Ankle/lower leg | 49 | 30 | |

| Forearm/wrist | 27 | 26 | |

| Shoulder | 21 | 17 | |

| Rib | 26 | 23 | |

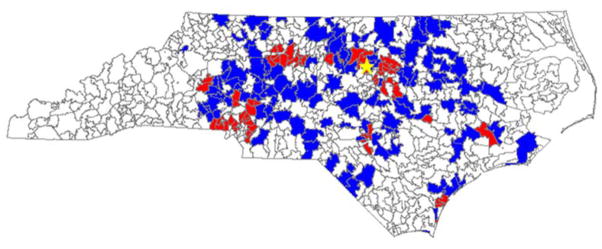

Figure 2 shows the geographic distribution of E-consults, during the study period. The total travel distance saved for rural Veterans who were managed with E-consult, assuming that 1 visit to the healthcare center was avoided for each Veteran, was 11,917 miles (19,178 kilometers), or 69.7 miles (112.2 kilometers) per person. Based on enrollment demographics within the VA Medical Center, there was a trend toward more rural patients receiving E-consults (171 completed vs. 149 expected). However, this was not statistically significant (P = 0.52). Within the rural cohort, bisphosphonates were recommended 51 times, with 33 (64.7%) ordered, compared to 50 recommended and 25 (50.0%) ordered within the urban cohort (P = 0.13). Within the rural cohort BMD was recommended 109 times with 79 (72.5%) ordered, compared to 88 recommended and 64 (72.3%) ordered, within the urban cohort. For both rural and urban cohorts, an in-person Endocrine-Bone consultation was recommended in 6.4% and 6.0%, respectively, due to medical complexity.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of Veterans with E-consults by ZIP code tabulation area. Blue = Rural, Red = Urban. Star = Coordinating Veterans Administration Medical Center location.

The bone health nurse liaison services began in Oct 2013 at the central VAMC and then expanded to 2 additional facilities starting in Jan 2014. During the study period, 118 individuals were followed by the bone health nurse liaison, of which 71 resided in a rural area (Table 2). In these patients, bisphosphonates were ordered in 75.8% of patients for whom treatment was recommended, compared to 39.7% of patients without nurse liaison involvement (P < 0.01). With regards to BMD assessment, testing was completed in 63.0% of patients followed by the nurse liaison, compared to 37.1% of those not followed by the nurse liaison (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the effect of the nurse liaison between rural and urban Veterans (P = 0.57 for bisphosphonate prescriptions, P = 0.20 for BMD testing).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Veterans with an E-consult by involvement of Bone Health Nurse Liaison

| With Nurse Liaison N = 118 |

Without Nurse Liaison N = 203 |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

|

| |||

| Age, mean ± SD | 69.8 ± 10.5 | 70.9 ± 10.7 | 0.39 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 28.2 ± 6.1 | 27.3 ± 6.2 | 0.23 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.90 | ||

| Male | 112 (94.9) | 192 (94.6) | |

| Female | 6 (5.1) | 11 (5.4) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.42 | ||

| White | 81 (68.6) | 144 (70.9) | |

| Black | 32 (27.1) | 43 (21.2) | |

| Other | 2 (1.7) | 5 (2.5) | |

| Unknown | 3 (2.5) | 11 (5.4) | |

|

| |||

| Comorbidities | |||

|

| |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 41 (34.8) | 77 (37.9) | 0.57 |

| Chronic lung disease | 28 (23.7) | 50 (24.6) | 0.86 |

| Neurologic disease | 17 (14.4) | 33 (16.3) | 0.66 |

| Alcohol abuse | 21 (18.1) | 39 (19.2) | 0.17 |

| Prostate Cancer | 10 (8.5) | 15 (7.4) | 0.72 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 (2.5) | 3 (1.5) | 0.67 |

| Anticonvulsant use | 23 (21.1) | 49 (24.3) | 0.53 |

| Corticosteroid use | 2 (1.8) | 3 (1.3) | 1.00 |

Discussion

Prior to the program start, testing and treatment rates in the participating VAMCs were <20%[24]. We had previously shown the effectiveness of an E-consult program on osteoporosis management. However, inclusion of a bone health nurse liaison to coordinate care and provide patient education significantly improved the rate of osteoporosis evaluation and treatment among Veterans with a recent low-trauma fracture, beyond the E-consult program to the primary care provider alone. The program was able to save a substantial number of travel miles for rural patients. Despite differences in local access to BMD testing, which was available exclusively within the urban VA Medical Center during the study period, there were no differences in rates of BMD testing or bisphosphonate prescriptions between rural and urban patients.

Fracture Liaison Services have been demonstrated to significantly improve osteoporosis screening and treatment rates and are also cost-effective, sometimes cost-saving, programs[21,27–29]. However, such programs may be inefficient or relatively more costly for small medical centers with lower fracture volumes. Moreover, osteoporosis testing and treatment decisions may be more complex in men or patients with multiple co-morbidities, requiring subspecialty physician input, that may not be available in rural locales[1,30]. The current E-consult service, a centralized Fracture Liaison Service, with surveillance of regional medical centers and affiliated outpatient clinics, maybe an effective strategy for healthcare systems where there are multiple centers with variable fracture volumes and complex patient characteristics. The service can also increase access in areas with more limited availability to subspecialty physician consultation and nurse education.

The limitations of the E-consult service should be considered. The surveillance and patient identification process depends on accurate and consistent coding of fractures by clinicians. Although fracture identification using administrative databases has been validated[31,32], it has not been in the VA setting. Moreover, rural patients may be more likely to seek care for fractures in non-VA local emergency departments and therefore not be identified through VA clinical data. While we likely missed some fracture patients who received care outside the VA system, it is reassuring that our E-consult service had a greater than expected proportion of fracture patients who were rural. The VA Health Administration has a well-established network of community-based outpatient clinics affiliated with regional medical centers, along with its integrated electronic health record. Thus, aspects of the current E-consult program may be unique to the VA system. However, given the increasing integration of health systems in the US and increasing use of electronic health records, the current E-program may serve as a model for a feasible, centralized service to increase access to specialized medical care.

In conclusion, a centralized, E-consult program with a bone health nurse liaison can efficiently provide specialty bone health services to patients residing in both rural and urban areas and substantially increase the assessment and management of Veterans with previously untreated osteoporosis. Further program improvements will include an assessment of the impact on long-term medication adherence and the development and integration of a falls prevention program delivered via bone health nurse liaison.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Project Award #N06-FY14Q1-S1-P01167 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. RHL, KWL and CCE acknowledge support from the Duke Claude D. Pepper OAIC (P30AG028716-08). RHL acknowledges support from the NIH/NIA GEMSSTAR (R03AG048119-02).

Contributor Information

Richard H. Lee, Email: r.lee@duke.edu, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC, USA. Duke University Medical Center, Department of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA.

Megan Pearson, Email: megan.pearson@va.gov, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC, USA.

Kenneth W. Lyles, Email: kenneth.lyles@dm.duke.edu, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC, USA. Duke University Medical Center, Department of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA. The Carolinas Center for Medical Excellence, Cary, NC, USA.

Patricia W. Jenkins, Email: patricia.jenkins2@va.gov, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC, USA.

Cathleen Colón-Emeric, Email: cathleen.colonemeric@dm.duke.edu, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Durham, NC, USA. Duke University Medical Center, Department of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA. The Carolinas Center for Medical Excellence, Cary, NC, USA.

References

- 1.Bass E, French DD, Bradham DD, Rubenstein LZ. Risk-adjusted mortality rates of elderly veterans with hip fractures. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17(7):514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA, Center JR. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301(5):513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trombetti A, Herrmann F, Hoffmeyer P, Schurch MA, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R. Survival and potential years of life lost after hip fracture in men and age-matched women. Osteoporosis International. 2002;13(9):731–737. doi: 10.1007/s001980200100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cree M, Soskolne CL, Belseck E, Hornig J, McElhaney JE, Bryant R, Suarez-Almazor M. Mortality and institutionalization following hip fracture. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(3):283–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scane AC, Francis RM, Sutcliffe AM, Francis MJ, Rawlings DJ, Chapple CL. Case-control study of the pathogenesis and sequelae of symptomatic vertebral fractures in men. Osteoporosis International. 1999;9(1):91–97. doi: 10.1007/s001980050120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burger H, Van Daele PL, Grashuis K, Hofman A, Grobbee DE, Schütte HE, Birkenhäger JC, Pols HA. Vertebral deformities and functional impairment in men and women. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1997;12(1):152–157. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matthis C, Weber U, O’Neill TW, Raspe H. Health impact associated with vertebral deformities: results from the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study (EVOS) Osteoporosis International. 1998;8(4):364–372. doi: 10.1007/s001980050076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders KM, Nicholson GC, Ugoni AM, Pasco JA, Seeman E, Kotowicz MA. Health burden of hip and other fractures in Australia beyond 2000. Projections based on the Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Medical Journal of Australia. 1999;170(10):467–470. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb127845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colon-Emeric C, Kuchibhatla M, Pieper C, Hawkes W, Fredman L, Magaziner J, Zimmerman S, Lyles KW. The contribution of hip fracture to risk of subsequent fractures: data from two longitudinal studies. Osteoporosis International. 2003;14(11):879–883. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1460-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA, 3rd, Berger M. Patients with prior fractures have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2000;15(4):721–739. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.4.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyles KW, Colon-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS, Adachi JD, Pieper CF, Mautalen C, Hyldstrup L, Recknor C, Nordsletten L, Moore KA, Lavecchia C, Zhang J, Mesenbrink P, Hodgson PK, Abrams K, Orloff JJ, Horowitz Z, Eriksen EF, Boonen S HORIZON Recurrent Fracture Trial. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(18):1799–1809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beaupre LA, Morrish DW, Hanley DA, Maksymowych WP, Bell NR, Juby AG, Majumdar SR. Oral bisphosphonates are associated with reduced mortality after hip fracture. Osteoporosis International. 2011;22(3):983–991. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Center JR, Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Nguyen TV, Eisman JA. Osteoporosis medication and reduced mortality risk in elderly women and men. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(4):1006–1014. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganda K, Puech M, Chen JS, Speerin R, Bleasel J, Center JR, et al. Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporosis International. 2013;24(2):393–406. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2090-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giangregorio L, Papaioannou A, Cranney A, Zytaruk N, Adachi JD. Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap: an international phenomenon. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;35(5):293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliot-Gibson V, Bogoch ER, Jamal SA, Beaton DE. Practice patterns in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporosis International. 2004;15(10):767–778. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldstein AC, Nichols G, Orwoll E, Elmer PJ, Smith DH, Herson M, et al. The near absence of osteoporosis treatment in older men with fractures. Osteoporosis International. 2005;16(8):953–962. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1950-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of the Inspector General. Management of Osteoporosis in Veterans with Fractures. VA Office of the Inspector General; Washington, DC: 2010. Report No. 09-03138-191. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C. The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporosis International. 2003;14(12):1028–1034. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1507-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dell R, Greene D, Schelkun SR, Williams K. Osteoporosis disease management: the role of the orthopaedic surgeon. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American volume. 2008;90(Suppl 4):188–194. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, Harrington JT, McKinney RE, Jr, McLellan A, et al. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2012;27(10):2039–2046. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gamm L, Hutchison L, Bellamy G, Dabney BJ. Rural healthy people 2010: identifying rural health priorities and models for practice. Journal of Rural Health. 2002;18(1):9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larson SL, Fleishman JA. Rural-urban differences in usual source of care and ambulatory service use: analyses of national data using Urban Influence Codes. Medical Care. 2003;41(7 Suppl):III65–III74. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000076053.28108.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee RH, Lyles KW, Pearson M, Barnard K, Colon-Emeric C. Osteoporosis screening and treatment among veterans with recent fracture after implementation of an electronic consult service. Calcified Tissue International. 2014;94(6):659–664. doi: 10.1007/s00223-014-9849-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colon-Emeric C, Lee R, Barnard K, Pearson M, Lyles KW. Use of regional clinical data to identify veterans for a multi-center osteoporosis electronic consult quality improvement intervention. Journal of Hospital Administration. 2013;2(1):8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsh D, Akesson K, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Boonen S, Brandi ML, et al. Coordinator-based systems for secondary prevention in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporosis International. 2011;22(7):2051–2065. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1642-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akesson K, Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, McLellan AR, Stenmark J, Pierroz DD, et al. Capture the Fracture: a Best Practice Framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporosis International. 2013;24(8):2135–2152. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2348-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLellan AR, Wolowacz SE, Zimovetz EA, Beard SM, Lock S, McCrink L, et al. Fracture liaison services for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture: a cost-effectiveness evaluation based on data collected over 8 years of service provision. Osteoporosis International. 2011;22(7):2083–2098. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khosla S, Amin S, Orwoll E. Osteoporosis in men. Endocrine reviews. 2008;29(4):441–464. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lix LM, Azimaee M, Osman BA, Caetano P, Morin S, Metge C, et al. Osteoporosis-related fracture case definitions for population-based administrative data. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:301. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Adams ML. Identification of fractures from computerized Medicare files. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45(7):703–714. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90047-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]