Abstract

Diabetics are at risk for a number of serious health complications including an increased incidence of epilepsy and poorer recovery after ischemic stroke. Astrocytes play a critical role in protecting neurons by maintaining extracellular homeostasis and preventing neurotoxicity through glutamate uptake and potassium buffering. These functions are aided by the presence of potassium channels, such as Kir4.1 inwardly rectifying potassium channels, in the membranes of astrocytic glial cells. The purpose of the present study was to determine if hyperglycemia alters Kir4.1 potassium channel expression and homeostatic functions of astrocytes. We used q-PCR, Western blot, patch-clamp electrophysiology studying voltage and potassium step responses and a colorimetric glutamate clearance assay to assess Kir4.1 channel levels and homeostatic functions of astrocytes grown in normal and high glucose conditions. We found that astrocytes grown in high glucose (25 mM) had an approximately 50% reduction in Kir4.1 mRNA and protein expression as compared with those grown in normal glucose (5 mM). These reductions occurred within 4 to 7 days of exposure to hyperglycemia, whereas reversal occurred between 7 to 14 days after return to normal glucose. The decrease in functional Kir channels in the astrocytic membrane was confirmed using barium to block Kir channels. In the presence of 100 μm barium, the currents recorded from astrocytes in response to voltage steps were reduced by 45%. Furthermore, inward currents induced by stepping extracellular [K+]o from 3 to 10 mM (reflecting potassium uptake) were 50% reduced in astrocytes grown in high glucose. In addition, glutamate clearance by astrocytes grown in high glucose was significantly impaired. Taken together, our results suggest that down-regulation of astrocytic Kir4.1 channels by elevated glucose may contribute to the underlying pathophysiology of diabetes-induced CNS disorders and contribute to the poor prognosis after stroke.

Keywords: astrocytes, hyperglycemia, Kir4.1 potassium channels, glutamate clearance, diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder that also affects the central nervous system (CNS) by raising brain glucose levels. These higher levels of glucose in the CNS result in a glucose neurotoxicity that can lead to abnormal brain function and trauma (Tomlinson and Gardiner, 2008). It is known that both type I and II diabetes increase seizure susceptibility especially in non-ketogenic hyperglycemic diabetic patients due to metabolic disturbances such as mild hyperosmolality (Lee et al., 2014). Moreover, it is well documented that people with diabetes are at greater risk for stroke when compared to non-diabetics and elevated blood glucose concentrations during stroke are associated with poor outcome (Desilles et al., 2013). High glucose concentrations within the CNS environment also affect astrocytes by increasing the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which lead to oxidative stress (Hsieh et al., 2013) as well as an increase in the production of inflammatory cytokines (Shin et al., 2014).

Astrocytes are the most abundant cells in the CNS and their function goes beyond being supportive cells for neurons (Jing et al., 2013). In normal conditions, astrocytes play a major role in the CNS by maintaining extracellular homeostasis of neuroactive substances such as K+, H+, GABA and glutamate. A more hyperpolarized membrane potential compared to neurons can be found in astrocytes which provides the necessary driving force for K+ spatial buffering and glutamate transport (Kucheryavykh et al., 2007, Kucheryavykh et al., 2009, Olsen, 2012).

A major ion channel expressed by astrocytes is the inward rectifying potassium channel Kir4.1 (encoded by the gene KCNJ10) (Steinhauser and Seifert, 2002, Seifert et al., 2009). This potassium channel is not only a key player in efficient uptake of K+ released by neurons during axon potential propagation (Neusch et al., 2006, Djukic et al., 2007, Chever et al., 2010), but these channels also influence the ability of glial glutamate transporters to clear glutamate from the synaptic space (Djukic et al., 2007, Kucheryavykh et al., 2007).

Dysfunction of normal astrocytes can compromise their ability to maintain extracellular homeostasis and can disrupt the normal function of neurons (Anderson et al., 2003). In addition, astrocyte dysfunction can lead to greater damage in response to an ischemic insult such as the one produced in stroke (Muranyi et al., 2006, Raghubir, 2007).

Studies aimed at determining the causes of diabetic retinopathy have shown reduction of connexin 26 and 43 gene and protein expression and corresponding functional deficits in Müller glial cells after 6 weeks of diabetes (Ly et al., 2011). It has also been demonstrated that protein levels of Kir4.1 and K+ inward current are decreased leading to a higher osmotic stress to the Müller glial cells in streptozotocin treated diabetic rats (Pannicke et al., 2006). In cultured Müller cells, hyperglycemia causes a reduction in both Kir4.1 and GLAST protein expression and these reductions could be reversed by administration of pigment epithelium-derived factor (Xie et al., 2012).

Although there have been conflicting reports about high glucose and diabetes altering glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) levels in astrocytes (Coleman et al., 2004, Guven et al., 2009, Nagayach et al., 2014), there is not much information about the consequences of high glucose levels on the function of brain astrocytes. The purpose of the current study was to determine the effect of high glucose on the expression and function of Kir4.1 potassium channels in astrocytes thereby affecting potassium and glutamate uptake by astrocytes.

1.0 Experimental Procedures

1.1 Astrocyte Primary Cultures

Primary cultures of astrocytes were prepared from neocortex of 1–2 day old rats as previously described (Kucheryavykh et al., 2007) and in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Briefly, brains were removed after decapitation and the meninges stripped away to minimize fibroblast contamination. The forebrain cortices were collected and dissociated using the stomacher blender method. The cell suspension was then allowed to filter by gravity through a #60 sieve and then through a #100 sieve. After centrifugation, the cells were suspended in 2 groups. One group was plated in normal glucose DMEM (containing 5 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 iU/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin). The second group was plated in high glucose DMEM where the glucose concentration was 25 mM. Both groups were plated in uncoated 75 cm2 flasks at a density of 300,000 cells/cm2. The medium was exchanged with the appropriate fresh culture medium about every 4 days. At confluence (about 12 days), the mixed glial cultures were treated with 50 mM leucine methylester (pH 7.4 in PBS) for 60 min to kill microglia (Simmons and Murphy, 1992). Cultures were then allowed to recover for at least one day in growth medium prior to experimentation. Astrocytes were dissociated by trypsinization and reseeded onto appropriate plates and cover glasses for the glutamate uptake study and for the patch clamp experiments.

1.2 Time Course Experiment

Two groups were studied according to the experimental design: 1) normal glucose to high glucose to see how rapidly Kir4.1 was downregulated and 2) high glucose to normal glucose to analyze when or if Kir4.1 protein levels recover. The medium changes were done over a period of 14 days using the following time points: 0, 7, 10, 12, 13 or 14 days and all cells were harvested at the same time. Therefore, the days of 0, 1, 2, 4, 7 or 14 after medium change were examined. As a control, astrocytes were cultured in 5 mM or 25 mM glucose and on days 0, 7, 10, 12, 13 or 14, the medium was exchanged for fresh medium containing the same initial 5 mM or 25 mM glucose. After 14 days the cells were lysed and prepared for protein level analysis by Western Blot. The results were expressed as percent of control and compared to astrocytes for which medium was changed, but the glucose concentration was kept the same (i.e., normal to normal or high to high glucose).

1.3 SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting Analysis

Astrocytes were harvested, pelleted and resuspended in homogenization buffer (pH 7.5) containing: (in mM) Tris-HCl 20, NaCl 150, EDTA 1.0, EGTA 1.0, Phenylmethylsulfonyl Fluoride (PMSF) 1.0 and 1% Triton X-100 and an additional mixture of peptide inhibitors (leupeptin, bestatin, pepstatin, and aprotinin). Lysates were mixed with Urea sample buffer (plus dithiothreitol), boiled, spun briefly to pellet debris, and immediately run on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Protein concentration of cell homogenates was determined with the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad), followed by addition of an appropriate volume of Urea sample buffer (62mM Tris/HCl pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 8M Urea, 20mM EDTA, 5% β-Mercaptoethanol, 0.015% Bromophenol Blue) for a final concentration of 0.5 – 1.5 μg protein/μl, and incubation in a water bath at 94°C for 10 min. Western blotting was performed as previously described (Kucheryavykh et al., 2007) using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Kir4.1 (1:400, Alomone, cat. # APC-035). Final detection was performed with enhanced chemiluminescence methodology (SuperSignal® West Dura Extended Duration Substrate; Pierce, Rockford, IL) as described by the manufacturer, and the intensity of the signal measured in a gel documentation system (Versa Doc Model 1000, Bio Rad). In all cases, intensity of the chemiluminescence signal was corrected for minor differences in protein content after densitometry analysis of the India ink stained membrane.

1.4 Real Time RT-PCR

Gene expression levels were determined by RT-PCR analysis for the KCNJ10 gene encoding Kir4.1. Total RNA (in 50 μL of water) was isolated using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). 500 ng of RNA sample was used for determination of Kir4.1 mRNA using the LightCycler Amplification SYBR green 1 kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim Germany). Typical amplification reactions (20 μL) contained 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM of each primer (validated sense and antisense primers for KCNJ10 gene; Qiagen cat. # QT00185402) and 2 μL of 10X LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I (Roche Diagnostics). PCR amplifications were carried out in glass capillary tubes (Roche Diagnostics). Reverse transcription was performed at 55°C for 600 s, and amplification began with a 30 s denaturation step at 95°C followed by 45 cycles of annealing at 55°C for 10 s and extension at 72°C for 13 s. The relative quantification method utilizing a standard curve was performed. We optimized the real time RT-PCR results by performing a standard curve for the mRNA using the LightCycler Control Kit DNA (Roche Diagnostics, cat. no. 12158833001). The data were analyzed using LightCycler Software (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

1.5 Colorimetric Glutamate Clearance Assay

To evaluate the glutamate clearance capacity, primary astrocyte cultures were trypsinized and plated in 24 well dishes. Glutamate remaining in the medium (bicarbonate balanced salt solution (BBSS) containing in mM: NaCl 127, KCl 3, NaHCO3 19.5, NaH2PO4 1.5, MgSO4 1.5, CaCl2 1 and 5 of glucose for normal glucose and 25 for high glucose astrocytes) was determined using the protocol of (Abe et al., 2000). Briefly, astrocytes were washed with BBSS and then 300 μl of BBSS containing 400 μM glutamate was added to the wells. After 60 min, the medium was removed and 50 μl of culture supernatant was transferred to 96-well culture plates and the colorimetric assay was performed. The production of MTT formazan was assessed by measurement of absorbance at 550 nm using a microplate reader (Wallac Victor, Perkin Elmer). A standard curve was constructed in each assay using cell-free BBSS containing known concentrations of glutamate. The concentration of extracellular glutamate in the samples was estimated from the standard curve ranging from 6.25 to 1000 μM glutamate. As a control for each experiment, BBSS containing 400 μM glutamate was added to empty wells of a 24 well dish (no astrocytes) and processed together with the astrocytes, i.e. 60 min in the incubator until sample collection. Since astrocytes grown in different glucose concentrations grow at different rates, glutamate clearance capability was normalized by estimating the cell numbers by protein extraction followed by a Bradford Assay to measure protein concentration.

1.6 Electrophysiology

Membrane potential (Em) was measured immediately after establishment of whole-cell configuration. Membrane currents were measured with the single electrode whole-cell patch-clamp technique. Two Narishige hydraulic micromanipulators (Narishige, MMW-203, Japan) were used for voltage-clamp recording, and positioning a micropipette with 30 – 50 μm tip diameter at a very close distance for rapid application of test solutions. The electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries (1B150F-4, World Precision Instruments, Inc., Sarasota, FL) in two steps using a Sutter P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments Corp. Novato, CA) and had a resistance of 4–6 MΩ after filling with intracellular solution (ICS). The ICS contained (in mM): K-gluconate 120, KCl 10, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1, EGTA 10, HEPES 10, spermine tetrahydrochloride 0.3, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH/HCl. After achieving whole-cell mode, access resistance was 10–15 MΩ, compensated by at least 75%. The extracellular solution (ECS) contained (in mM): NaCl 145, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 2, and HEPES 10; KCl varied from 1.0 to 10 mM (substituted by NaCl to adjust osmolarity). High frequencies (>1 kHz) were cut off, using an Axon multiclamp-700B amplifier and a CV-203BU headstage, and digitized at 5 kHz through a DigiData 1322A interface (Axon Instruments, Molecular Probes, Sunnyvale, CA). The pClamp 9 (Axon Instruments) software package was used for data acquisition and analysis.

1.7 Analysis of Data

All data collected from Western blot, RT-PCR and glutamate clearance experiments were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Data from time course experiments were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Data from glutamate clearance experiments, RT-PCR and Western blot were analyzed using the Student’s paired t-test. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

2.0 Results

2.1 Kir4.1 mRNA and protein expression are decreased in astrocytes grown in hyperglycemic conditions

To evaluate the effect that high glucose may have on astrocytic Kir4.1 potassium channel expression, we cultured astrocytes in either control DMEM with 5 mM glucose or high glucose DMEM with 25 mM glucose. After two weeks in culture, we determined the levels of Kir4.1 mRNA and protein using RT-PCR and Western blotting, respectively. Kir4.1 mRNA levels were significantly decreased (20% of control ± 9 SEM) in astrocytes grown in high glucose relative to control (Fig. 1A). Similarly, astrocytes grown in high glucose showed a significant decrease (53% of control ± 10 SEM) in Kir4.1 protein levels as compared to astrocytes grown in control glucose (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Kir 4.1 potassium channel mRNA and protein levels are lower in astrocytes grown in DMEM containing high glucose as compared with normal glucose.

(A) Kir4.1 potassium channel mRNA levels (mean ± SEM) obtained from astrocytes grown in normal and high glucose were determined using quantitative real time RT-PCR. Kir4.1 mRNA levels were significantly down-regulated in astrocytes grown in high glucose (n=4 for both groups; *p<0.05).

(B) Kir4.1 potassium channel protein levels (relative chemiluminescence intensity ± SEM) were determined by Western blot using astrocytes grown in normal and high glucose (representative Western blots shown above the graph). Protein levels of Kir4.1 were significantly down-regulated in astrocytes grown in high glucose (n=4 for both groups; *p<0.05). Kir4.1 was detected as a band with molecular weight of approximately 43kDa. Data are expressed as % of control with control being astrocytes grown in normal glucose.

(C) Representative western blot for Kir4.1 and the India ink stained membrane as a protein loading control. In all experiments, intensity of the chemiluminescence signal was corrected for minor differences in protein content after densitometry analysis of the India ink stained membrane.

2.2 Expression changes in Kir4.1 potassium channels are reversible

To determine how rapidly Kir4.1 protein levels decreased when grown in high glucose, we examined the time course of down-regulation of Kir4.1 potassium channel protein in astrocytes after exposure to elevated glucose. To address this we initially cultured astrocytes in 5 mM glucose and the medium was changed to one containing 25 mM glucose and Kir4.1 protein levels were assessed after 0, 1, 2, 4, 7 or 14 days in high glucose. As control, astrocytes were maintained in 5 mM glucose medium. After exposing astrocytes from control to high glucose (Fig. 2A), we found a significant down regulation of Kir4.1 protein by day 7 (67% of control ± 9 SEM) which was maintained for the duration of the experiment (day 14; 56% of control ± 8 SEM).

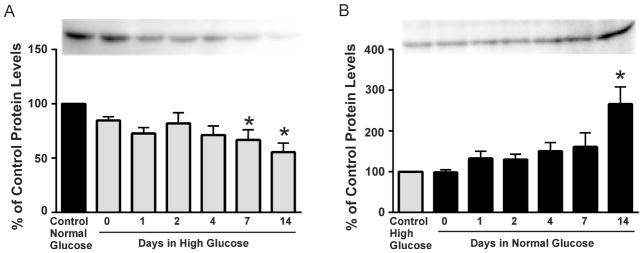

Figure 2. Time course experiments examining alterations in Kir4.1 potassium channel protein levels.

(A) Kir4.1 potassium channel protein levels (relative chemiluminescence intensity ± SEM) were determined by Western blot using astrocytes grown initially in normal (5mM) glucose and then switched to high (25mM) glucose-containing medium for 0, 1, 2, 4, 7 or 14 days (representative Western blots shown above the graph). Kir4.1 potassium channel protein levels were reduced by 7 days when astrocytes were switched from normal to high glucose medium (*p<0.05, n=5).

(B) Kir4.1 potassium channel protein levels (relative chemiluminescence intensity ± SEM) were determined by Western blot using astrocytes grown initially in high (25mM) glucose and then switched to normal (5mM) glucose-containing medium for 0, 1, 2, 4, 7 or 14 days (representative Western blots shown above the graph). Protein levels of Kir4.1 were up-regulated by day 14 when astrocytes were switched from high to normal glucose medium (*p<0.05, n=6).

In a parallel group of experiments, we determined whether or not down-regulation of Kir4.1 channels in astrocytes grown in high 25 mM glucose was reversible after switching the medium to one containing normal 5 mM glucose. In this experiment, control astrocytes were maintained in 25 mM glucose medium. A significant recovery of Kir4.1 protein levels was observed by day 14 (266% of 25 mM glucose control ± 42 SEM; n=6) when astrocytes were switched from high to control glucose medium (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that decreases in astrocytic Kir4.1 protein which occur during hyperglycemia are not permanent; i.e., they can be recovered once the glucose levels are back to normal.

2.3 K+ uptake is reduced in astrocytes grown in high glucose

We used a physiologically relevant protocol to test the ability of astrocytes to buffer potassium by measuring membrane currents elicited in response to an extracellular K+ step (Skatchkov et al., 1995, Skatchkov et al., 1999, Zhou et al., 2000, Kucheryavykh et al., 2007, Inyushin et al., 2010). Whole cell patch clamp recordings were done at holding potential equal to the cell membrane potential (−61.6 mV ± 2.0 SEM for control glucose and −60.6 mV ± 2.8 SEM for high glucose) with constant whole cell bath perfusion. Inward currents were induced by increasing [K+]o from 3mM to 10mM whereas outward currents were induced by stepping [K+]o from 3mM to 1mM. Representative current traces and the summary of the results are shown in Fig. 3. Cortical astrocytes grown in DMEM containing normal 5mM glucose displayed inward currents of −244 pA ± 41 SEM (n =23) while astrocytes grown in high 25mM glucose displayed significantly decreased inward currents of −122 pA ± 30 SEM (n =14). These data suggest that potassium uptake by astrocytes grown in high glucose is impaired.

Figure 3. Responses of astrocytes grown in normal and high glucose to changes in [K+]o, i.e. potassium steps.

(A) Summary of the current responses of astrocytes grown in normal (5mM) or high (25mM) glucose to changes in [K+]o. The astrocytes were bathed in a solution containing 3 mM K+ and this solution was changed to 1 or 10 mM K+ (n=23 and 14 cells for the normal and high glucose groups, respectively). The currents induced by altering the external concentrations of K+ were measured using the whole-cell voltage-clamp technique. Astrocytes were clamped at Eh which was equal to the resting membrane potential (Em) in 3 mM [K+]o, Eh=Em. Results are expressed as current (pA) ± SEM.

(B and C) Representative whole cell current traces obtained by stepping K+ from 3 mM to 1 mM followed by 10 mM K+ for astrocytes grown in normal (B) or high (C) glucose. There was no significant difference between the mean membrane potentials of astrocytes grown in control glucose (−61.6 mV ± 2.0 SEM) or high glucose (−60.6 mV ± 2.8 SEM).

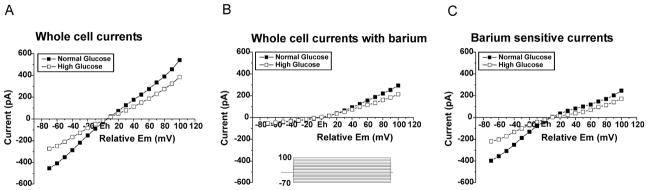

2.4 Contribution of Kir channels to whole cell currents is reduced in astrocytes grown in high glucose

In order to measure the total contribution of Kir channels to whole cell currents measured from astrocytes, we applied a voltage step protocol (100 ms steps to potentials between 70 mV negative to and 100 mV positive to the holding potential) and used barium (100 μM), a selective blocker of Kir channels (Reichelt and Pannicke, 1993, Skatchkov et al., 1995). The cells were held at a potential (Eh) equal to resting cell potential (Em) which was −61.6 mV ± 2.0 SEM and −60.6 mV ± 2.8 SEM for astrocytes grown in control and high glucose, respectively. The voltage steps were then applied from the holding potential. Because the membrane potentials of both groups of astrocytes were similar, the steps ranged from approximately −130 mV to +40 mV. The steps evoked both inward and outward currents that were substantially larger in astrocytes grown in normal glucose (Figure 4A). Upon application of the Kir channel blocker, Ba2+ (100 μM), currents in astrocytes were inhibited, particularly in the inward direction (Figure 4B) representing block of inwardly rectifying Kir channels. The magnitude of inhibition was much greater in astrocytes cultured in normal glucose. This is reflected as the significantly larger barium sensitive currents (obtained by subtraction of recordings with barium (Fig. 4B) from total whole cell currents in absence of barium (Fig. 4A)) as shown in Fig. 4C. The Kir current amplitudes (barium sensitive currents, Fig. 4C) measured at −70 mV from Em for astrocytes grown in control glucose (−397 pA ± 42; n=22) vs. high glucose (−219 pA ± 4; n=18) were almost twice larger. Taken together, the smaller current elicited from astrocytes grown in hyperglycemic conditions and the reduced response to Ba2+ application indicate that functional (membrane) Kir channel activity is substantially reduced in astrocytes grown in 25mM glucose as compared with those grown in 5mM glucose.

Figure 4. Barium-sensitive (Kir) currents are reduced in astrocytes grown in high glucose as compared with normal glucose.

Rat cortical astrocytes were cultured in DMEM containing normal (5 mM) or high (25 mM) glucose for two weeks and then plated on coverslips. Astrocytes were clamped at Eh which was equal to the resting membrane potential (Em) in 3 mM [K+]o, Eh=Em. I/V-curves are shown in response to a voltage step protocol (100 ms voltage steps to potentials between 70 mV negative and 100 mV positive from the holding potential (Eh)).

(A) Whole cell currents recorded from astrocytes grown in normal (n=22) and high glucose (n=18) in response to a voltage ramp protocol.

(B) Whole cell currents recorded from astrocytes grown in normal (n=22) and high glucose (n=18) in response to a voltage ramp protocol in the presence of 100 μM Ba2+ (a blocker of Kir channels).

(C) Barium sensitive currents from astrocytes grown in normal (n=22) and high glucose (n=18). The graph shows the subtraction of currents obtained in the presence of barium (B) from total whole cell currents shown in (A). Barium-sensitive currents reflect the contribution of Kir channels to the whole cell currents. There was no significant difference between the mean membrane potentials of astrocytes grown in control glucose (−61.6 mV ± 2.0 SEM) or high glucose (−60.6 mV ± 2.8 SEM).

2.5 Glutamate clearance by astrocytes grown in high glucose is impaired

Because decreased expression of Kir4.1 channel subunits has been associated with decreased glutamate clearance by astrocytes (Djukic et al., 2007, Kucheryavykh et al., 2007), we next examined the glutamate uptake capability of astrocytes cultured in control or high glucose using a colorimetric assay (Abe et al., 2000). We found that astrocytes grown in DMEM containing high glucose (25mM) clear less glutamate than astrocytes grown in DMEM with 5mM glucose. The 5mM glucose astrocytes cleared 52% of the glutamate, whereas the 25 mM glucose astrocytes only cleared 27% of the glutamate in 60 minutes (Fig. 5). Taken together these data suggest that glutamate clearance by astrocytes grown in elevated glucose is impaired.

Figure 5. Glutamate clearance is reduced in astrocytes grown in DMEM containing high glucose as compared with normal glucose.

Rat cortical astrocytes were plated in normal (5 mM) and high (25 mM) glucose-containing DMEM for 2 weeks and on the day of the experiment were incubated for 60 min with 300μl of 400μM glutamate. Using a colorimetric assay, the concentrations of glutamate were measured after 60min and compared with the concentrations of glutamate measured in the absence of astrocytes. Data are expressed as % of control glutamate. Glutamate clearance was significantly lower (*p<0.05) in astrocytes grown in DMEM containing high glucose (n=16 for normal glucose and 18 for high glucose). Data were normalized based on total protein concentrations.

3.0 Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated down-regulation of Kir4.1 channels as well as impaired glutamate uptake in retinal Müller glial cells exposed to hyperglycemic/diabetic conditions in both cell culture and whole animal models (Pannicke et al., 2006, Zhang et al., 2011, Xie et al., 2012). Here we show using biochemical and electrophysiological techniques that hyperglycemia decreases expression and functional activity of astrocytic Kir4.1 potassium channels and impairs potassium uptake and glutamate clearance by astrocytes.

The implications of our findings are two-fold; the first practical and the second theoretical. First, most laboratories use cultured cells that are grown in high glucose containing medium although many papers do not document the concentration of glucose in the methods sections. Our study demonstrates that astrocytes grown in high glucose have altered expression of a key astrocytic protein, the Kir4.1 potassium channel, and also altered homeostatic functions. Other alterations in astrocytic proteins and function in response to hyperglycemia have been reported including reduced gap-junctional communication between astrocytes (Gandhi et al., 2010) and increased production of cytokines and reactive oxygen species (Wang et al., 2012). Taken together, these data stress the importance of considering glucose concentration in cell culture medium as part of the experimental design.

The second implication of our findings is related to stroke-induced brain damage. People who are hyperglycemic when they have a stroke are 3 times more likely to die and also suffer more severe permanent damage if they survive the stroke. There have been numerous theories to try to explain this, including increased corticosterone levels (Payne et al., 2003), neutrophil infilitration (Lin et al., 2000), increased cerebral lactate resulting in local brain tissue acidosis (Kagansky et al., 2001), changes in cerebral blood flow (Akamatsu et al., 2015) protein O-glycosylation (Martin et al., 2006), among others, however, the specific mechanism(s) of how high glucose levels exacerbate damage after stroke remains unclear. Here we propose that downregulation of Kir4.1 potassium channels in astrocytes may be a major contributing factor to explain hyperglycemia exacerbated ischemic damage via lack of both glutamate and potassium clearance in hyperglycemic astrocytes.

Indeed, it has been reported that neurons are less sensitive to ischemic damage if they are surrounded by astrocytes (Cervos-Navarro and Diemer, 1991) suggesting that astrocytes are capable of protecting the neurons from an ischemic insult. But, what could be the result of an ischemic insult if the astrocytes already show impaired function because of the high glucose levels?

To understand this we should look first at the consequences of knock-out of Kir4.1 in astrocytes on potassium homeostasis in normal conditions. Chever et al., (2010) investigated the consequences of conditional knock-out of Kir4.1 in glial cells of mice in vivo. They found that the membrane potential of hippocampal astrocytes was significantly depolarized (by greater than 20 mV) and the potassium permeability was reduced as one would expect. Surprisingly, there was only a modest impairment in potassium clearance from the extracellular space in response to neuronal stimulation; this was manifested as a slower recovery of [K+]o levels after neuronal stimulation. Because extracellular potassium levels were not severely impaired in response to neuronal stimulation, it seems that other pathways such as the sodium potassium ATPase function to maintain extracellular potassium homeostasis under normal conditions. Indeed, (D’Ambrosio et al., 2002) demonstrated that Kir channels and the neuronal/glial sodium potassium ATPases interact to maintain extracellular K+ homeostasis in response to neuronal firing.

During ischemia, the blood flow to an area of the brain is compromised resulting in a lack of glucose and oxygen to the region. In these conditions, even anaerobic glycolysis fails, ATP becomes depleted and the neuronal/glial sodium potassium ATPases are inhibited (Lees, 1991). Therefore, one of the pathways to maintain potassium homeostasis is impaired. On the other hand, in patients with hyperglycemia, the Kir4.1 potassium channels may also be down-regulated (as we show here in cultured astrocytes) which would further compromise potassium uptake and buffering and decrease neuronal survival in response to the ischemic event. Kir4.1 channels work rapidly while the sodium potassium ATPase is slow: this difference is very important in terms of rapid removal of excess external potassium.

In hyperglycemic conditions, we show here that astrocytes also have diminished capacity to clear glutamate. Although our studies do not show if this is due to down-regulation of astrocytic glutamate transporters or decreased activity of these transporters due to loss of Kir4.1 channels, the result is the same. More glutamate in the extracellular space to promote excitotoxic neuronal cell death.

Decrease of Kir4.1 channels in astrocytes has been described in multiple conditions, including intractable mesio-temporal lobe epilepsy (Bordey and Sontheimer, 1998), Huntington’s disease (Tong et al., 2014), hepatic encephalopathy (Obara-Michlewska et al., 2011) and traumatic brain injury (D’Ambrosio et al., 1999) where the severity of Kir4.1 loss increases with aging (Gupta and Prasad, 2013) In the case of mesio-temporal lobe epilepsy, seizure-associated reactive astrocytes expressed enhanced sodium conductance and decreased potassium conductance (Bordey and Sontheimer, 1998). Hyperglycemia has been shown to increase sodium conductance in dorsal root ganglion cells (Singh et al., 2013) so a similar alteration in sodium dynamics may increase spiking probability and could potentially contribute to the increased seizures observed in diabetic patients (Sabitha et al., 2001, Younes et al., 2014).

3.1 Conclusions

Taken together, our findings suggest that astrocytes in the hyperglycemic brain have impairment of two of their main homeostatic functions: potassium buffering and glutamate uptake. This provides a neurotoxic environment where neurons are susceptible to overexcitation leading to a cascade of reactions that could end with neuronal apoptosis (Liu et al., 2006, Bell et al., 2007).

Highlights.

The effect of hyperglycemia on astrocytic potassium channel function was studied.

Hyperglycemia decreases astrocytic Kir4.1 mRNA and protein levels.

Hyperglycemia impairs K+ buffering and glutamate clearance by astrocytes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Paola López Pieraldi and Natalia Skachkova for their superior technical assistance. This publication was made possible by NIH-NIGMS-SC1-GM088019, NIH-NINDS-R01-NS065201, NIH-NIMHD-G12-MD007583, NIH-NIGMS-R25GM110513, NIH-NIGMS-SC2-GM095410 and Dept. of Education Title V PPOHA P031M105050.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

David E. Rivera-Aponte, Email: david.rivera11@upr.edu.

Miguel P. Méndez-González, Email: miguel.mendez3@upr.edu.

Aixa F. Rivera-Pagán, Email: aixafernanda@gmail.com.

Yuriy V. Kucheryavykh, Email: k_yurii@hotmail.com.

Lilia Y. Kucheryavykh, Email: kuc-lilia@mail.ru.

Serguei N. Skatchkov, Email: sergueis64@gmail.com.

Misty J. Eaton, Email: misty.eaton@uccaribe.edu.

References

- Abe K, Abe Y, Saito H. Evaluation of L-glutamate clearance capacity of cultured rat cortical astrocytes. Biol Pharm Bull. 2000;23:204–207. doi: 10.1248/bpb.23.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akamatsu Y, Nishijima Y, Lee CC, Yang SY, Shi L, An L, Wang RK, Tominaga T, Liu J. Impaired leptomeningeal collateral flow contributes to the poor outcome following experimental stroke in the Type 2 diabetic mice. J Neurosci. 2015;35:3851–3864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3838-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MF, Blomstrand F, Blomstrand C, Eriksson PS, Nilsson M. Astrocytes and stroke: networking for survival? Neurochem Res. 2003;28:293–305. doi: 10.1023/a:1022385402197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell JD, Ai J, Chen Y, Baker AJ. Mild in vitro trauma induces rapid Glur2 endocytosis, robustly augments calcium permeability and enhances susceptibility to secondary excitotoxic insult in cultured Purkinje cells. Brain. 2007;130:2528–2542. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordey A, Sontheimer H. Properties of human glial cells associated with epileptic seizure foci. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32:286–303. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervos-Navarro J, Diemer NH. Selective vulnerability in brain hypoxia. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1991;6:149–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chever O, Djukic B, McCarthy KD, Amzica F. Implication of Kir4.1 channel in excess potassium clearance: an in vivo study on anesthetized glial-conditional Kir4.1 knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15769–15777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2078-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Judd R, Hoe L, Dennis J, Posner P. Effects of diabetes mellitus on astrocyte GFAP and glutamate transporters in the CNS. Glia. 2004;48:166–178. doi: 10.1002/glia.20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio R, Gordon DS, Winn HR. Differential role of KIR channel and Na(+)/K(+)-pump in the regulation of extracellular K(+) in rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:87–102. doi: 10.1152/jn.00240.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio R, Maris DO, Grady MS, Winn HR, Janigro D. Impaired K(+) homeostasis and altered electrophysiological properties of post-traumatic hippocampal glia. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8152–8162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08152.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desilles JP, Meseguer E, Labreuche J, Lapergue B, Sirimarco G, Gonzalez-Valcarcel J, Lavallee P, Cabrejo L, Guidoux C, Klein I, Amarenco P, Mazighi M. Diabetes mellitus, admission glucose, and outcomes after stroke thrombolysis: a registry and systematic review. Stroke. 2013;44:1915–1923. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukic B, Casper KB, Philpot BD, Chin LS, McCarthy KD. Conditional knock-out of Kir4.1 leads to glial membrane depolarization, inhibition of potassium and glutamate uptake, and enhanced short-term synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11354–11365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0723-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi GK, Ball KK, Cruz NF, Dienel GA. Hyperglycaemia and diabetes impair gap junctional communication among astrocytes. ASN Neuro. 2010;2:e00030. doi: 10.1042/AN20090048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Prasad S. Early down regulation of the glial Kir4.1 and GLT-1 expression in pericontusional cortex of the old male mice subjected to traumatic brain injury. Biogerontology. 2013;14:531–541. doi: 10.1007/s10522-013-9459-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven A, Yavuz O, Cam M, Comunoglu C, Sevi’nc O. Central nervous system complications of diabetes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: a histopathological and immunohistochemical examination. Int J Neurosci. 2009;119:1155–1169. doi: 10.1080/00207450902841723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HL, Lin CC, Hsiao LD, Yang CM. High glucose induces reactive oxygen species-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and cell migration in brain astrocytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:601–614. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8442-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inyushin M, Kucheryavykh LY, Kucheryavykh YV, Nichols CG, Buono RJ, Ferraro TN, Skatchkov SN, Eaton MJ. Potassium channel activity and glutamate uptake are impaired in astrocytes of seizure-susceptible DBA/2 mice. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1707–1713. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing L, He Q, Zhang JZ, Li PA. Temporal profile of astrocytes and changes of oligodendrocyte-based myelin following middle cerebral artery occlusion in diabetic and non-diabetic rats. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:190–199. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagansky N, Levy S, Knobler H. The role of hyperglycemia in acute stroke. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1209–1212. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.8.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucheryavykh LY, Kucheryavykh YV, Inyushin M, Shuba YM, Sanabria P, Cubano LA, Skatchkov SN, Eaton MJ. Ischemia Increases TREK-2 Channel Expression in Astrocytes: Relevance to Glutamate Clearance. Open Neurosci J. 2009;3:40–47. doi: 10.2174/1874082000903010040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucheryavykh YV, Kucheryavykh LY, Nichols CG, Maldonado HM, Baksi K, Reichenbach A, Skatchkov SN, Eaton MJ. Downregulation of Kir4.1 inward rectifying potassium channel subunits by RNAi impairs potassium transfer and glutamate uptake by cultured cortical astrocytes. Glia. 2007;55:274–281. doi: 10.1002/glia.20455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Jung J, Kang K, Park JM, Shin H, Kwon O, Kim BK. Recurrent seizures following focal motor status epilepticus in a patient with non-ketotic hyperglycemia and acute cerebral infarction. J Epilepsy Res. 2014;4:28–30. doi: 10.14581/jer.14007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees GJ. Inhibition of sodium-potassium-ATPase: a potentially ubiquitous mechanism contributing to central nervous system neuropathology. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1991;16:283–300. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(91)90011-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Ginsberg MD, Busto R, Li L. Hyperglycemia triggers massive neutrophil deposition in brain following transient ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2000;278:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00889-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Liao M, Mielke JG, Ning K, Chen Y, Li L, El-Hayek YH, Gomez E, Zukin RS, Fehlings MG, Wan Q. Ischemic insults direct glutamate receptor subunit 2-lacking AMPA receptors to synaptic sites. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5309–5319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0567-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly A, Yee P, Vessey KA, Phipps JA, Jobling AI, Fletcher EL. Early inner retinal astrocyte dysfunction during diabetes and development of hypoxia, retinal stress, and neuronal functional loss. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:9316–9326. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Rojas S, Chamorro A, Falcon C, Bargallo N, Planas AM. Why does acute hyperglycemia worsen the outcome of transient focal cerebral ischemia? Role of corticosteroids, inflammation, and protein O-glycosylation. Stroke. 2006;37:1288–1295. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000217389.55009.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muranyi M, Ding C, He Q, Lin Y, Li PA. Streptozotocin-induced diabetes causes astrocyte death after ischemia and reperfusion injury. Diabetes. 2006;55:349–355. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayach A, Patro N, Patro I. Astrocytic and microglial response in experimentally induced diabetic rat brain. Metab Brain Dis. 2014;29:747–761. doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9562-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neusch C, Papadopoulos N, Muller M, Maletzki I, Winter SM, Hirrlinger J, Handschuh M, Bahr M, Richter DW, Kirchhoff F, Hulsmann S. Lack of the Kir4.1 channel subunit abolishes K+ buffering properties of astrocytes in the ventral respiratory group: impact on extracellular K+ regulation. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1843–1852. doi: 10.1152/jn.00996.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara-Michlewska M, Pannicke T, Karl A, Bringmann A, Reichenbach A, Szeliga M, Hilgier W, Wrzosek A, Szewczyk A, Albrecht J. Down-regulation of Kir4.1 in the cerebral cortex of rats with liver failure and in cultured astrocytes treated with glutamine: Implications for astrocytic dysfunction in hepatic encephalopathy. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:2018–2027. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen M. Examining potassium channel function in astrocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;814:265–281. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-452-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannicke T, Iandiev I, Wurm A, Uckermann O, vom Hagen F, Reichenbach A, Wiedemann P, Hammes HP, Bringmann A. Diabetes alters osmotic swelling characteristics and membrane conductance of glial cells in rat retina. Diabetes. 2006;55:633–639. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne RS, Tseng MT, Schurr A. The glucose paradox of cerebral ischemia: evidence for corticosterone involvement. Brain Res. 2003;971:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghubir R. Emergin Role of Astrocytes in Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Ann Neurol. 2007:15. [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt W, Pannicke T. Voltage-dependent K+ currents in guinea pig Muller (glia) cells show different sensitivities to blockade by Ba2+ Neurosci Lett. 1993;155:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90663-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabitha KM, Girija AS, Vargese KS. Seizures in hyperglycemic patients. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:723–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert G, Huttmann K, Binder DK, Hartmann C, Wyczynski A, Neusch C, Steinhauser C. Analysis of astroglial K+ channel expression in the developing hippocampus reveals a predominant role of the Kir4.1 subunit. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7474–7488. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3790-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin ES, Huang Q, Gurel Z, Sorenson CM, Sheibani N. High glucose alters retinal astrocytes phenotype through increased production of inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons ML, Murphy S. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in glial cells. J Neurochem. 1992;59:897–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb08328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JN, Jain G, Sharma SS. In vitro hyperglycemia enhances sodium currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons: an effect attenuated by carbamazepine. Neuroscience. 2013;232:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skatchkov SN, Krusek J, Reichenbach A, Orkand RK. Potassium buffering by Muller cells isolated from the center and periphery of the frog retina. Glia. 1999;27:171–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skatchkov SN, Vyklicky L, Orkand RK. Potassium currents in endfeet of isolated Muller cells from the frog retina. Glia. 1995;15:54–64. doi: 10.1002/glia.440150107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser C, Seifert G. Glial membrane channels and receptors in epilepsy: impact for generation and spread of seizure activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;447:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01846-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson DR, Gardiner NJ. Glucose neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nrn2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong X, Ao Y, Faas GC, Nwaobi SE, Xu J, Haustein MD, Anderson MA, Mody I, Olsen ML, Sofroniew MV, Khakh BS. Astrocyte Kir4.1 ion channel deficits contribute to neuronal dysfunction in Huntington’s disease model mice. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:694–703. doi: 10.1038/nn.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Li G, Wang Z, Zhang X, Yao L, Wang F, Liu S, Yin J, Ling EA, Wang L, Hao A. High glucose-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species in cultured astrocytes. Neuroscience. 2012;202:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie B, Jiao Q, Cheng Y, Zhong Y, Shen X. Effect of pigment epithelium-derived factor on glutamate uptake in retinal Muller cells under high-glucose conditions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:1023–1032. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younes S, Cherif Y, Aissi M, Alaya W, Berriche O, Boughammoura A, Frih-Ayed M, Zantour B, Habib Sfar M. Seizures and movement disorders induced by hyperglycemia without ketosis in elderly. Iran J Neurol. 2014;13:172–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xu G, Ling Q, Da C. Expression of aquaporin 4 and Kir4.1 in diabetic rat retina: treatment with minocycline. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:464–479. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Schools GP, Kimelberg HK. GFAP mRNA positive glia acutely isolated from rat hippocampus predominantly show complex current patterns. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;76:121–131. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]