Abstract

Background

The issue of patient volume related to trauma outcomes is still under debate. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between number of severely injured patients treated and mortality in German trauma hospitals.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of the TraumaRegister DGU® (2009–2013). The inclusion criteria were patients in Germany with a severe trauma injury (defined as Injury Severity Score (ISS) of at least 16), and with data available for calculation of Revised Injury Severity Classification (RISC) II score. Patients transferred early were excluded. Outcome analysis (observed versus expected mortality obtained by RISC‐II score) was performed by logistic regression.

Results

A total of 39 289 patients were included. Mean(s.d.) age was 49·9(21·8) years, 27 824 (71·3 per cent) were male, mean(s.d.) ISS was 27·2(11·6) and 10 826 (29·2 per cent) had a Glasgow Coma Scale score below 8. Of 587 hospitals, 98 were level I, 235 level II and 254 level III trauma centres. There was no significant difference between observed and expected mortality in volume subgroups with 40–59, 60–79 or 80–99 patients treated per year. In the subgroups with 1–19 and 20–39 patients per year, the observed mortality was significantly greater than the predicted mortality (P < 0·050). High‐volume hospitals had an absolute difference between observed and predicted mortality, suggesting a survival benefit of about 1 per cent compared with low‐volume hospitals. Adjusted logistic regression analysis (including hospital level) identified patient volume as an independent positive predictor of survival (odds ratio 1·001 per patient per year; P = 0·038).

Conclusion

The hospital volume of severely injured patients was identified as an independent predictor of survival. A clear cut‐off value for volume could not be established, but at least 40 patients per year per hospital appeared beneficial for survival.

Short abstract

No clear volume cut‐off

Introduction

The relationship between hospital volume and trauma outcomes is under debate, with several cut‐offs proposed1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. Centralization and creation of trauma systems and centres are based on a perceived volume–outcome benefit, but the exact number of patients and their corresponding severity of injury are not clear across studies1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma requires a minimum of 1200 patient admissions for level I trauma centres; 240 (20·0 per cent) of these are supposed to have an Injury Severity Score (ISS) of at least 167. In Germany, the issue of patient volume or caseload is controversial. There already exist requirements for a clearly defined number of operations and interventions, for example with regard to transplantations or endoprostheses. The effect of patient volume on mortality among patients with major trauma is not yet clear and it is not possible to make general recommendations7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. With a view to improving the quality of care, the present study aimed to analyse the effect of patient volume on mortality in German trauma centres. This may also have implications for other European countries.

Trauma centres in Germany are divided into three categories: level I, II and III. The essential function of local trauma centres (level III) is the nationwide care of the most common moderate injuries. These centres also serve as the first point of contact for patients who have suffered a major trauma, especially when primary transportation to a regional or supraregional trauma centre is not possible. Certain quality standards for infrastructure and procedure must be fulfilled. Regional trauma centres (level II) are responsible for comprehensive emergency and definitive care of the severely injured. Their requirements include the constant presence of specialists with advanced training in special trauma surgery. Supraregional trauma centres (level I) have specific tasks and responsibilities in the care of multiply injured patients, especially those with exceptionally complex or rare injury patterns20.

This study assessed whether the requirement for a clearly defined patient volume has any effect on mortality of patients with severe injuries (ISS at least 16). The potential impact of annual hospital patient volume on survival was investigated. It was hypothesized that a high patient volume has a positive impact on survival.

Methods

The study received full approval from the ethics committee of the medical faculty of Technical University Munich, Germany (project number 431/14). The present study is in line with the publication guidelines of the TraumaRegister DGU® (ID number 2013‐065) and adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) recommendations for cohort studies21.

Data collection – TraumaRegister DGU®

In 1993, a working group on polytrauma started TraumaRegister DGU®. Since then multicentre data on patients with polytrauma have been collected prospectively in the participating countries, including Germany, Austria, Switzerland and China among several others. Specific information is gathered relating to the medical treatment of patients who have experienced major trauma, such as treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU) or the trauma room. The data are entered into a web‐based server. The organization of documentation is provided by the Academy for Trauma Surgery (AUC – Akademie der Unfallchirurgie, Berlin, Germany), a company affiliated to the German Trauma Society, whereas the scientific leadership is provided by the Committee on Emergency Medicine, Intensive Care and Trauma Management (Section NIS) of the German Trauma Society. Participating hospitals are supposed to record data from patients admitted to hospital via the emergency room with subsequent ICU treatment, or patients who reach hospital with vital signs and die before ICU treatment. The register includes parameters such as ISS, injury pattern, co‐morbidities, laboratory findings and diagnostic or epidemiological data. Since 2009, hospitals participating in the German trauma network (TraumaNetzwerk DGU®) have been obliged to record their data in the TraumaRegister DGU®20, 22, 23.

Patients

In this retrospective multicentre cohort study, mortality was analysed according to the mean number of patients treated in one hospital per year (patient volume). The analysis included German patients who were admitted to hospital between 2009 and 2013 with severe injuries, defined as an ISS of at least 16, and had data available for calculation of Revised Injury Severity Classification (RISC) II score22, 24.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who were transferred in or out early (within the first 48 h) were excluded because Revised Injury Severity Classification (RISC) II score and outcome respectively are not available for these patients.

For each trauma centre a mean number of patients per year was calculated. Any hospital year since 2009 with a difference of more than 50 per cent between the reported annual number of severely injured patients and the mean number of severely injured patients was excluded; only the specific year in which such deviation occurred was excluded. For example, it is possible that a hospital documented a mean of 43 procedures per year from 2009 to 2013. If this hospital reported only seven procedures in 2010, the patients treated at this hospital in 2010 were excluded. This was done because there is a high risk of bias owing to under‐reporting (case completeness questionable).

Revised Injury Severity Classification II

The TraumaRegister DGU® used the conventional RISC score for outcome adjustment from 2003. However, some limitations of this score became apparent with time. It used ten different variables for prediction, which made it difficult to provide complete data for all patients. The percentage of patients with an available RISC prognosis repeatedly fell below the desired rate of 90 per cent. Thus, a considerable number of patients could not be included in comparative analyses. Furthermore, RISC was developed with data from 1993 to 2000, which led to an overestimation of risk of death in recent years. Since 2006, the observed mortality rate has been about 2 per cent below the predicted rate24.

Therefore, a new scoring system was developed: the updated RISC‐II score. It consists of the following variables: worst and second worst injury, head injury, age, sex, pupil reactivity and size, preinjury health status, blood pressure, acidosis (base deficit), coagulation, haemoglobin and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Missing values were included as a separate category for each variable. RISC‐II outperformed the original RISC score in the development (30 866 patients from 2010 and 2011) and validation (21 918 patients from 2012) data sets. Discrimination, precision and calibration improved significantly. For example, the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was 0·953 (discrimination), precision was high (11·0 per cent predicted versus 10·7 per cent observed mortality) and calibration was 38·3 per cent (Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness‐of‐fit statistic)24. In summary, RISC‐II is one of the most precise scores for risk of death prediction in severely injured patients.

Statistical analysis

Six subgroups were formed based on the annual number of patients in the interval 2009–2013. The groups were not formed on the basis of the mean number of patients over the whole period. Thus a particular hospital could be in the category ‘30–49’ in one year and ‘50–69’ in another. Outcome analysis was done by calculating the RISC‐II score for the standardized mortality ratio (SMR; observed/expected mortality). Hospital mortality was the primary endpoint. Hospital outcome was then compared with the outcome predicted by RISC‐II (prognosis), and SMRs with 95 per cent c.i. were calculated for each subgroup based on a Poisson distribution.

A multivariable logistic regression analysis with survival as dependent variable was performed. The independent predictors were RISC‐II score (continuous), number of patients per year (continuous) and hospital level of care (categorical)25. The significance level was set at P = 0·050. SPSS® version 22 was used (IBM, Ehningen, Germany).

Results

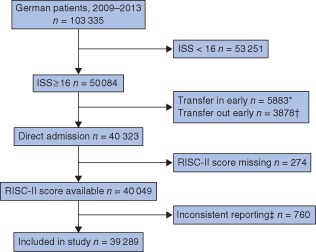

Some 39 289 of 103 335 injured patients met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Patients with an ISS lower than 16 were excluded (53 251), as well as those who were transferred in (5883) or out within 48 h (3878). Furthermore, trauma centres with a difference of more than 50 per cent between their reported annual number of patients and mean number of patients since 2009 were excluded (760).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. *Patients transferred in were excluded owing to missing data for the prehospital phase (Revised Injury Severity Classification (RISC) II score was not calculable). †Patients transferred out early (within 48 h) were excluded as final outcome data were not available. ‡For each trauma centre, a mean number of patients per year was calculated. ISS, Injury Severity Score

The main characteristics of the investigated patients are summarized in Table 1; further details are provided in Table S1 (supporting information). Mean(s.d.) age was 49·9(21·8) years, 71·3 per cent (27 824) were male, the mean(s.d.) ISS was 27·2(11·6) and 95·8 per cent (35 684) had blunt injuries. Some 16·9 per cent of the patients (5880) were in shock at the scene and 29·2 per cent (10 826) had a Glasgow Coma Scale score below 8. Most of the patients (36 138) were admitted to the ICU. There were no relevant differences between low‐ and high‐volume hospitals with regard to age, sex and mechanism of injury.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort

| Hospital volume (patients per year) | Total (n = 39 289) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–19 (n = 7654) | 20–39 (n = 8264) | 40–59 (n = 6961) | 60–79 (n = 5761) | 80–99 (n = 4694) | ≥100 (n = 5955) | ||

| Age (years)* | 53·2(22·1) | 50·2(21·7) | 49·3(21·7) | 48·4(21·4) | 47·3(21·6) | 49·2(21·8) | 49·9(21·8) |

| Men | 5339 (69·9) | 5850 (71·3) | 4906 (71·1) | 4173 (73·1) | 3378 (72·7) | 4178 (70·3) | 27 824 (71·3) |

| Blunt injury | 6794 (95·9) | 7438 (95·9) | 6385 (95·8) | 5309 (96·4) | 4348 (95·8) | 5410 (94·6) | 35 684 (95·8) |

| Shock at scene | 928 (13·9) | 1197 (16·1) | 1074 (17·4) | 943 (18·7) | 783 (18·3) | 955 (18·0) | 5880 (16·9) |

| Whole‐body CT | 5466 (71·9) | 6751 (82·4) | 5744 (83·2) | 4967 (86·9) | 3957 (84·6) | 5036 (84·9) | 31 921 (81·8) |

| AIS head ≥ 3 | 2812 (36·7) | 4158 (50·3) | 3864 (55·5) | 3203 (55·6) | 2700 (57·5) | 3468 (58·2) | 20 205 (51·4) |

| AIS thorax ≥ 3 | 4660 (60·9) | 4930 (59·7) | 3805 (54·7) | 3209 (55·7) | 2669 (56·9) | 3297 (55·4) | 22 570 (57·4) |

| AIS abdomen ≥ 3 | 1375 (18·0) | 1389 (16·8) | 1117 (16·0) | 952 (16·5) | 752 (16·0) | 890 (14·9) | 6475 (16·5) |

| AIS extremities ≥ 3 | 2525 (33·0) | 2734 (33·1) | 2255 (32·4) | 1946 (33·8) | 1585 (33·8) | 1860 (31·2) | 12 905 (32·8) |

| Injury Severity Score* | 24·9(9·9) | 27·0(11·4) | 27·5(11·7) | 27·9(11·7) | 28·7(12·2) | 28·1(12·4) | 27·2(11·6) |

| ICU admission | 6839 (89·4) | 7652 (92·6) | 6498 (93·3) | 5356 (93·0) | 4330 (92·2) | 5463 (91·7) | 36138 (92·0) |

| Duration of ICU stay (days)* | 7·3(10·8) | 9·4(12·5) | 9·7(12·6) | 10·1(13·1) | 10·6(13·2) | 10·7(14·4) | 9·5(12·8) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean(s.d.). Data are incomplete for some variables. AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale; ICU, intensive care unit.

Of the 587 hospitals, 98 were level I, 235 level II and 254 level III trauma centres (Table 2). The mean number of patients with major trauma treated per year was 58·0 in level I, 15·6 in level II and 3·3 in level III hospitals. Level I hospitals provided medical care for 24 945 (63·5 per cent) of the 39 289 patients, level II hospitals for 12 184 (31·0 per cent) and level III hospitals for 2160 (5·5 per cent). Most of the level III hospitals did not treat more than 20 of these injured patients per year, whereas most level II hospitals did not treat more than 40 patients per year. Level I hospitals usually treated more than 40 patients with major trauma injuries per year.

Table 2.

Number of hospitals and number of patients per hospital per year according to hospital level

| Level I | Level II | Level III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 24 945 (63·5) | 12 184 (31·0) | 2160 (5·5) |

| No. of hospitals | 98 | 235 | 254 |

| No. of patients per year since 2009 | |||

| Mean(s.d.) | 58·0(31·3) | 15·6(13·2) | 3·3(3·6) |

| 1–19 | 421 (5·5) | 5219 (68·2) | 2014 (26·3) |

| 20–39 | 3492 (42·3) | 4626 (56·0) | 146 (1·8) |

| 40–59 | 5518 (79·3) | 1443 (20·7) | 0 (0) |

| 60–79 | 5132 (89·1) | 629 (10·9) | 0 (0) |

| 80–99 | 4427 (94·3) | 267 (5·7) | 0 (0) |

| ≥100 | 5955 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise.

Outcome analysis

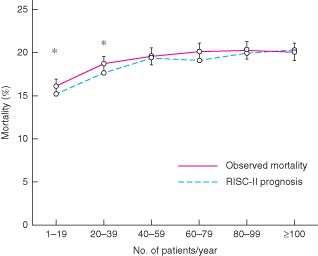

Outcome data regarding overall mortality rate, RISC‐II prognosis and SMR are shown in Table 3. Differences between observed and expected mortality within the subgroups are shown in Fig. 2. In hospitals with fewer than 100 patients per year, the observed hospital mortality rate was 0·2 to 1·0 per cent higher than the expected mortality.

Table 3.

Outcomes related to annual hospital volume

| Hospital volume (patients per year) | Total (n = 39 289) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–19 (n = 7654) | 20–39 (n = 8264) | 40–59 (n = 6961) | 60–79 (n = 5761) | 80–99 (n = 4694) | ≥ 100 (n = 5955) | ||

| Non‐survivors | 1235 | 1544 | 1361 | 1159 | 951 | 1195 | 7445 |

| Observed mortality (%) | 16·1 | 18·7 | 19·6 | 20·1 | 20·3 | 20·1 | 18·9 |

| (15·3, 17·0) | (17·8, 9·5) | (18·6, 20·5) | (19·1, 21·2) | (19·1, 21·4) | (19·0, 21·1) | (18·6, 19·3) | |

| RISC‐II‐predicted mortality (%) | 15·2 | 17·7 | 19·4 | 19·1 | 19·7 | 20·3 | 18·3 |

| Difference between observed and predicted mortality | 0·9 | 1·0 | 0·2 | 1·0 | 0·6 | −0·2 | 0·6 |

| SMR | 1·06 | 1·06 | 1·01 | 1·05 | 1·03 | 0·98 | 1·04 |

| (1·01, 1·12)* | (1·01, 1·11)* | (0·96, 1·06) | (0·99, 1·11) | (0·97, 1·09) | (0·93, 1·04) | (1·01, 1·06)* | |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent c.i. RISC, Revised Injury Severity Classification; SMR, standardized mortality ratio (observed/expected mortality).

P < 0·050 (t test).

Figure 2.

Difference between observed mortality and expected mortality (Revised Injury Severity Classification (RISC) II prognosis) for each volume subgroup P < 0·050 (t test)

In the subgroups with 40–59, 60–79 or 80–99 patients per year, there was no significant difference between observed and expected mortality. In the subgroups with 1–19 and 20–39 patients per year, the SMRs and the lower end of the 95 per cent c.i. were above 1, meaning that the observed mortality in these groups was significantly greater than the predicted mortality. In the group with 100 or more patients per year, the observed mortality was −0·2 per cent lower than predicted (SMR less than 1).

In logistic regression analysis including RISC‐II score and patient volume (model 1), patient volume as a continuous variable was identified as an independent and significant positive predictor of survival (odds ratio 1·001 per patient per year; P = 0·005) (Table 4). The model suggests, in theory, that for a hospital with 50 severely injured patients per year (odds ratio 1.00150 = 1.05) the chance to survive is increased by 5 per cent for any given patient compared with a hospital with only one severely injured patient per year. Further, for a hospital with 100 severely injured patients per year (odds ratio 1.001100 = 1.11) the chance to survive is increased by 11 per cent compared with a hospital with one such patient per year within this model.

Table 4.

Adjusted model for prediction of survival based on Revised Injury Severity Classification II score and patient volume

| Coefficient | Odds ratio (eβ) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RISC‐II score* | 0·953 | 2·59 (2·54, 2·65) | < 0·001 |

| Patient volume (per patient)† | 0·001 | 1·001 (1·000, 1·002) | 0·005 |

| Constant | −0·110 | – | 0·002 |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent c.i. The logistic regression analysis included 39 289 patients; survival was the dependent variable.

Inverse logistic transformation of the predicted outcome probability of Revised Injury Severity Classification (RISC) II score (mortality);

continuous dependent variable. Nagelkerke's R 2 = 0·583.

When hospital level was added (model 2), patient volume remained a stable and robust positive predictor of survival (odds ratio 1·001 per patient per year; P = 0·038) (Table S2, supporting information). The effect of patient volume seemed to be more pronounced than hospital level, which was not significant in this model (P ≥ 0·475).

Discussion

In this study, an increasing hospital volume of severely injured patients was an independent, significant and positive predictor of survival. Although a clear cut‐off value could not be established, it appears that at least 40 patients per year per hospital might be enough to improve survival. High‐volume hospitals had an absolute difference between observed and predicted mortality, suggesting a survival benefit of about 1 per cent compared with low‐volume hospitals. In rural districts, local level III trauma centres provide primarily life‐saving trauma care. This study demonstrated appropriate outcomes achieved by such hospitals.

Several recently published studies1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 have addressed the issue of a clearly defined patient volume for American trauma centres. In a systematic review7, a large number of studies between 1976 and 2013 were investigated for any correlation between patient volume and mortality8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 26, 27. In this summary of the North American literature, the correlation between patient volume and mortality was not proven. Only five studies14, 16, 17, 19, 26 regarded patient volume per hospital as a positive indicator of mortality; the others did not report such a correlation. Another study27 found that patient volumes exceeding 1000 per year were associated with a disadvantage in survival (inclusion criteria ISS over 15). In the latter study, mid‐volume hospitals treating between 500 and 1000 patients per year had the best survival rates; beyond the threshold value, survival rates declined27. The depletion of resources could be the reason for this. However, one other study8 did not confirm this effect.

Limitations of the review by Caputo and colleagues7 include the discrepancy between the methods of analysis, data sources, patient group composition and definition of the number of patients. Furthermore, the inclusion and exclusion criteria within the examined abstracts varied considerably. The limited number of patients and the mismatch between the registers used make it difficult to draw general recommendations. The impact of patients' age, ISS and status of hospital transfer was unclear. In addition, the study focused on American trauma centres14, 16, 17, 19, 26 so that conclusions regarding general validity are not possible.

Nathens and colleagues16 showed that patients with severe penetrating abdominal injuries and shock benefit most from treatment in trauma centres with more than 650 severely injured patients per year. Most of the patients (90 per cent) with similar injury patterns, but without shock, would not benefit from treatment at such trauma centres.

Another study10 investigated the effect of the ACS trauma centre designation and trauma volume on outcomes among patients with specific severe injuries. Data from the National Trauma Data Bank were used. Inclusion criteria were patients older than 14 years with an ISS above 15 who were still alive on admission to hospital. The authors adjusted the results for age, sex, mechanism of injury, ISS and hypotension on admission. Level I trauma centres had significantly lower mortality and significantly lower rates of severe disability at discharge than level II centres. The study showed a difference between level I and II centres for specific injury complexes, but no difference between high‐ and low‐volume centres. The volume of trauma admissions with an ISS above 15 did not have any effect on outcome in hospitals of both levels. Level I trauma centres had better outcomes, especially for specific injuries associated with high mortality rates10.

The issue of patient volume has been debated by the German Trauma Society in the context of the trauma centre accreditation. The trauma centres are divided into three categories – supraregional, regional and local – according to their resources. Participating in the TraumaNetzwerk DGU®, each trauma centre has to fulfil clearly defined standards for structure, process and outcome quality, as well as criteria for expertise and capacity20.

On the other hand, the German Statutory Accident Insurance (DGUV) specifies requirements for hospital approval to treat patients with severe and moderate occupational trauma, so‐called SAV or VAV accreditation respectively. To provide a high quality of trauma care, this regulatory authority clearly specifies numbers of operations (250 pelvic or spinal operations per year for severe trauma). A large number of structural characteristics are defined exactly, such as the provision of a trauma room of at least 50 m2 or 24 h availability of CT.

Variation in mortality between ACS‐verified and state‐designated level I and level II centres was evaluated over a period of 16 years, in a study that included 900 274 subjects9 and compared SMR and high‐mortality outliers. Level I ACS centres had a lower SMR than state‐designated level I centres: 0·95 (95 per cent c.i. 0·82 to 1·05) versus 1·02 (0·87 to 1·15) (P < 0·010); however, there was no difference in the number of outliers. By contrast, level II centres had similar SMRs, but state‐designated level II centres had higher SMR outliers than ACS level II centres. ACS verification was an independent predictor of survival in level II centres (odds ratio 1·26, 95 per cent c.i. 1·20 to 1·32; P < 0·010), but not in level I centres (P = 0·84). The study concluded that level II centres especially benefited from ACS verification9.

In Germany, the local trauma centres provide primary life‐saving trauma care, especially in rural districts. Although the number of severely injured patients per year is small, the present data indicate that these hospitals provide appropriate medical care as there was just a small difference between the expected and observed mortality of about 1 per cent. Thus, it appears that the German system of trauma networks with designated level I, level II and level III hospitals seems to work well28, 29.

This study has some limitations. It has a retrospective design, and its validity depends on the accuracy and availability of the medical records. Although the RISC‐II score has many advantages over the previous RISC score, 274 of 40 323 patients with missing data in the TraumaRegister DGU® had to be excluded. It remains unclear to what extent hospitals implemented the concept of advanced trauma life support and used homogeneous standards to grade injuries. Consequently, potential patient and treatment selection bias has to be considered. The study has no information about clinical confounders such as physician's expertise or availability of subspecialties including trauma surgery, neurosurgery or thoracic surgery. Furthermore, there are slight differences between subgroups, such as a lower ISS in low‐volume trauma centres. However, an adjustment was made for severity based on RISC‐II calculations to minimize this potential confounding effect.

Potential structural and geographical differences between the German regions could not be taken into consideration, but might have influenced the results. It is acknowledged that the findings are applicable primarily to the German system of trauma care, and that the findings show associations rather than causal relationships.

Supporting information.

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1 Characteristics of the study cohort (Word document)

Table S2 Adjusted model 2 for prediction of survival based on Revised Injury Severity Classification II score, patient volume and hospital level (Word document)

Supporting information

Characteristics of the study cohort

Adjusted model 2 for prediction of survival based on Revised Injury Severity Classification II score, patient volume and hospital level

Acknowledgements

The authors thank F. Seidl for professional language editing. Participating hospitals are listed at: www.traumaregister.de.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Metcalfe D, Bouamra O, Parsons NR, Aletrari MO, Lecky FE, Costa ML. Effect of regional trauma centralization on volume, injury severity and outcomes of injured patients admitted to trauma centres. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morrison JJ, McConnell NJ, Orman JA, Egan G, Jansen JO. Rural and urban distribution of trauma incidents in Scotland. Br J Surg 2013; 100: 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Minei JP, Fabian TC, Guffey DM, Newgard CD, Bulger EM, Brasel KJ et al Increased trauma center volume is associated with improved survival after severe injury: results of a Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium study. Ann Surg 2014; 260: 456–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gruen RL, Gabbe BJ, Stelfox HT, Cameron PA. Indicators of the quality of trauma care and the performance of trauma systems. Br J Surg 2012; 99(Suppl 1): 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tepas JJ III, Pracht EE, Orban BL, Flint LM. High‐volume trauma centers have better outcomes treating traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 74: 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davenport RA, Tai N, West A, Bouamra O, Aylwin C, Woodford M et al A major trauma centre is a specialty hospital not a hospital of specialties. Br J Surg 2010; 97: 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caputo LM, Salottolo KM, Slone DS, Mains CW, Bar‐Or D. The relationship between patient volume and mortality in American trauma centres: a systematic review of the evidence. Injury 2014; 45: 478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bennett KM, Vaslef S, Pappas TN, Scarborough JE. The volume–outcomes relationship for United States level I trauma centers. J Surg Res 2011; 167: 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown JB, Watson GA, Forsythe RM, Alarcon LH, Bauza G, Murdock AD et al American College of Surgeons trauma center verification versus state designation: are level II centers slipping through the cracks? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 75: 44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Demetriades D, Martin M, Salim A, Rhee P, Brown C, Chan L. The effect of trauma center designation and trauma volume on outcome in specific severe injuries. Ann Surg 2005; 242: 512–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glance LG, Osler TM, Dick A, Mukamel D. The relation between trauma center outcome and volume in the National Trauma Databank. J Trauma 2004; 56: 682–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. London JA, Battistella FD. Is there a relationship between trauma center volume and mortality? J Trauma 2003; 54: 16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konvolinka CW, Copes WS, Sacco WJ. Institution and per‐surgeon volume versus survival outcome in Pennsylvania's trauma centers. Am J Surg 1995; 170: 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marcin JP, Romano PS. Impact of between‐hospital volume and within‐hospital volume on mortality and readmission rates for trauma patients in California. Crit Care Med 2004; 32: 1477–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Margulies DR, Cryer HG, McArthur DL, Lee SS, Bongard FS, Fleming AW. Patient volume per surgeon does not predict survival in adult level I trauma centers. J Trauma 2001; 50: 597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Maier RV, Grossman DC, MacKenzie EJ, Moore M et al Relationship between trauma center volume and outcomes. JAMA 2001; 285: 1164–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pasquale MD, Peitzman AB, Bednarski J, Wasser TE. Outcome analysis of Pennsylvania trauma centers: factors predictive of nonsurvival in seriously injured patients. J Trauma 2001; 50: 465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richardson JD, Schmieg R, Boaz P, Spain DA, Wohltmann C, Wilson MA et al Impact of trauma attending surgeon case volume on outcome: is more better? J Trauma 1998; 44: 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marx WH, Simon R, O'Neill P, Shapiro MJ, Cooper AC, Farrell LS et al The relationship between annual hospital volume of trauma patients and in‐hospital mortality in New York State. J Trauma 2011; 71: 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie (German Trauma Society) . Whitebook – Medical Care of the Severely Injured (2nd revised and updated edn); 2012. www.dgu‐traumanetzwerk.de [accessed 17 May 2015]. [Google Scholar]

- 21. STROBE Statement . http://www.strobe‐statement.org/ [accessed 26 March 2015].

- 22. Committee on Emergency Medicine , Intensive Care and Trauma Management of the German Trauma Society (Sektion NIS). TraumaRegister DGU® Annual Report 2014 www.traumaregister.de [accessed 17 May 2015].

- 23. Ruchholtz S, German Society of Trauma Surgery. [External quality management in the clinical treatment of severely injured patients.] Unfallchirurg 2004; 107: 835–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lefering R, Huber‐Wagner S, Nienaber U, Maegele M, Bouillon B. Update of the trauma risk adjustment model of the TraumaRegister DGU: the Revised Injury Severity Classification, version II. Crit Care 2014; 18: 476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lefering R. Strategies for comparative analyses of registry data. Injury 2014; 45(Suppl 3): S83–S88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith RF, Frateschi L, Sloan EP, Campbell L, Krieg R, Edwards LC et al The impact of volume on outcome in seriously injured trauma patients: two years' experience of the Chicago Trauma System. J Trauma 1990; 30: 1066–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tepas JJ III, Patel JC, DiScala C, Wears RL, Veldenz HC. Relationship of trauma patient volume to outcome experience: can a relationship be defined? J Trauma 1998; 44: 827–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ruchholtz S, Lewan U, Debus F, Mand C, Siebert H, Kuhne CA. TraumaNetzwerk DGU®: optimizing patient flow and management. Injury 2014; 45(Suppl 3): S89–S92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ruchholtz S, Lefering R, Lewan U, Debus F, Mand C, Siebert H et al Implementation of a nationwide trauma network for the care of severely injured patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014; 76: 1456–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characteristics of the study cohort

Adjusted model 2 for prediction of survival based on Revised Injury Severity Classification II score, patient volume and hospital level