Abstract

Leukocyte trafficking to the small and large intestines is tightly controlled to maintain intestinal immune homeostasis, mediate immune responses, and regulate inflammation. A wide array of chemoattractants, chemoattractant receptors, and adhesion molecules expressed by leukocytes, mucosal endothelium, epithelium, and stromal cells controls leukocyte recruitment and microenvironmental localization in intestine and in the gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALTs). Naive lymphocytes traffic to the gut-draining mesenteric lymph nodes where they undergo antigen-induced activation and priming; these processes determine their memory/effector phenotypes and imprint them with the capacity to migrate via the lymph and blood to the intestines. Mechanisms of T-cell recruitment to GALT and of T cells and plasmablasts to the small intestine are well described. Recent advances include the discovery of an unexpected role for lectin CD22 as a B-cell homing receptor GALT, and identification of the orphan G-protein–coupled receptor 15 (GPR15) as a T-cell chemoattractant/trafficking receptor for the colon. GPR15 decorates distinct subsets of T cells in mice and humans, a difference in species that could affect translation of the results of mouse colitis models to humans. Clinical studies with antibodies to integrin α4β7 and its vascular ligand mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 are proving the value of lymphocyte trafficking mechanisms as therapeutic targets for inflammatory bowel diseases. In contrast to lymphocytes, cells of the innate immune system express adhesion and chemoattractant receptors that allow them to migrate directly to effector tissue sites during inflammation. We review the mechanisms for innate and adaptive leukocyte localization to the intestinal tract and GALT, and discuss their relevance to human intestinal homeostasis and inflammation.

Keywords: Leukocyte Trafficking, Chemokine Receptors, Adhesion Molecules, Intestine

Naive lymphocytes leave the bone marrow and thymus and circulate through secondary lymphoid tissues such as peripheral lymph nodes (PLNs), spleen, and gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALTs). With some exceptions,1,2 naive B and T cells are excluded from accessing tertiary sites such as the intestine lamina propria until they encounter their cognate antigen and up-regulate selective homing molecules that allow them to migrate to specific extralymphoid tissues under homeostasis and inflammatory conditions. The trafficking programs of lymphocytes are highly regulated and vary during their lifespan—they target lymphocytes to different tissues and within tissues to specialized microenvironments.

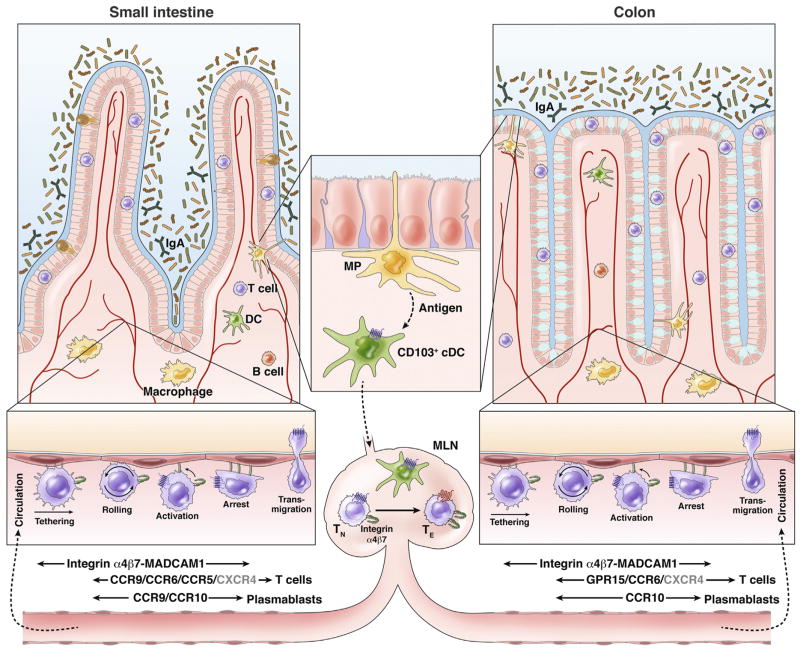

Recruitment of lymphocytes from the circulation into tissues is directed through a multistep process of lymphocyte–endothelial recognition. In this process, expression of complementary trafficking receptors on lymphocytes and endothelial cells mediates access to extravascular tissues.3–7 The steps involved comprise a coordinated series of interactions of adhesion and signaling molecules (Figure 1). Classically, engagement of lymphocyte adhesion molecules on microvilli with their vascular ligands causes cells to tether and roll on blood vessel endothelial surface. In some settings, rolling must be slowed by additional adhesion receptors. Chemoattractant receptors activated by chemokines or other ligands induce the firm integrin-dependent arrest of lymphocytes under shear flow. Chemoattractants also mediate the diapedesis of the cells through the vascular endothelium and into specific microenvironments. Recent studies have described remarkably sophisticated molecular specialization and regulation at each step in this cascade, and the reader is referred to recent reviews for further information.8,9 Combinatorial association of chemoattractant and adhesion receptors allows for diversity of tissue and microenvironment-specific targeting.10,11

Figure 1.

Small intestine and colon homing of lymphocytes. Antigens in the intestine are captured and processed by intestinal mononuclear phagocytes (MP), which include macrophages and DCs. DCs that have taken up antigen then up-regulate CCR7 expression, which directs their migration to GALT (eg, MLN) where they induce differentiation of naive T cells (TN) into regulatory or effector T cells (TE), and imprint them with trafficking receptors that direct them to the intestines. Localization of T and B cells to the small intestine (left) is mediated by α4β7 (which binds the vascular addressin MADCAM1) and CCR9. Expression of CCR10 together with α4β7 targets plasmablasts to the large intestine. Expression of α4β7 and GPR15, as well as additional chemoattractant receptor(s), mediates T-cell homing to the colon (right). As discussed in the text, CCR6 can direct T-cell recruitment to the intestines during inflammation but not during homeostasis; CCR5 may help direct Treg recruitment to the chronically inflamed distal small intestine, and CXCR4 may contribute to T-cell localization to the small and large intestine (gray letters).

In this review, we highlight the mechanisms and molecules that control leukocyte trafficking to the small and large intestines and to the GALT. We focus primarily on lymphocyte homing, but also consider mechanisms and control of dendritic and myeloid cell recruitment to the gastrointestinal tract. We discuss recent advances and their potential human relevance.

Homing of Naive and Memory Lymphocytes to GALT

Naive and central memory lymphocytes circulate through lymphoid tissues in search of antigens. They are recruited from the blood into lymph nodes and the GALT via high endothelial venules (HEVs). GALT HEVs are distinguished from the venules of most nonintestinal tissues by their high expression of the mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1 (MADCAM1).12 MADCAM1 is a receptor for the lymphocyte integrin α4β7,13–16 the target of vedolizumab recently approved for treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The integrin α4β7 is up-regulated on lymphocytes activated by migratory (lamina propria–derived) retinoic acid–presenting dendritic cells (DCs) in the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs).17 This integrin directs B and T immunoblasts specific for gut antigens back to the intestines (see later) or GALT, and central memory cells to Peyer’s patches (PPs) and the MLN. MADCAM1 also contains a mucin domain that is modified extensively with O-linked carbohydrates, including functionally specialized ligands for L-selectin (CD62L) and likely for the B-cell lectin CD22 (also known as Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins 2 [Siglec2]),18 discussed later.

HEVs in GALT express chemokine CCL21, which induces adhesion and chemotaxis through CCR7, expressed on naive and central memory T and B cells. In PPs, follicle-associated CXCL13 as well as widely expressed CXCL12 also contribute to B-cell recruitment.19 PLN HEVs express peripheral lymph node addressin,20 which comprises branched high-affinity, high-avidity, L-selectin binding sites (core 1/core 2 branched 6-sulfo-sialyl lewis X determinants). MLN HEVs express peripheral lymph node addressin, MADCAM1, or both: similar to the spleen, the MLN is therefore a site where memory cells for peripheral and mucosal antigens can intermingle.

In contrast to PLN and MLN, PP HEVs show a reduced density of L-selectin–binding glycotopes, and these appear to be of lower affinity as well. They are less highly sulfated and branched, and lack the MECA79 (monoclonal antibody recognizing peripheral lymph node addressin) epitope (reviewed by Lee et al18). As a consequence, L-selectin supports tethering but only very loose, rapid rolling on PP HEV; and without α4β7, lymphocytes rarely are recruited.21 Engagement of MADCAM1 with integrin α4β7 (in its constitutively low-affinity state on microvilli) serves to brake the rolling cells, slowing them sufficiently to respond to chemokine signals, which then can trigger integrin α4β7- and lymphocyte function–associated antigen-1 intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1)-dependent arrest.16,21

A role for integrin α4β7 in mediating mucosal B-cell responses is indicated by the inability of β7-deficient mice (Itgb7−/−) to mount antigen-mediated intestinal IgA responses.22 Moreover, antibody against α4β7 inhibits normal responses to oral antigen (oral cholera vaccine), without affecting the response to systemic immunization (parenteral hepatitis B vaccine).23

CD22 (Siglec2): a B-Cell Homing Receptor for PPs

GALTs, especially the PPs, are a major site of B-cell activation by intestinal antigens, leading to the generation of gut-homing plasmablasts that produce secretory IgA (reviewed by Mora and von Andrian24). In support of this process, PPs attract large numbers of circulating B cells as compared with PLNs.25 Similar to T cells, naive B cells use L-selectin and integrin α4β7 to recognize PP HEVs. Their arrest on HEVs is mediated via chemokines that include the CCR7 ligand CCL21, the CXCR4 ligand CXCL12, and the CXCR5 ligand CXCL13.19,26 CXCL13 is produced by cells within the B-cell follicles, and confers selective adhesion of B (but not T) cells in HEVs at the follicular border;19,26–28 this is a refined example of local microenvironmental control of lymphocyte–endothelial interactions.

Recent data, however, have shown a critical role for the B cell lectin CD22 and GALT HEV-specific carbohydrate ligands in the selective homing of B cells to PPs.18 St6gal1 is expressed preferentially by PP HEVs (not by PLN HEVs or capillary endothelial cells). St6gal1 encodes a β-galactose α-2,6 sialyltransferase that produces α-2,6-linked glycans that bind the B cell CD22; and CD22-fragment crystallizable region selectively binds PP HEVs.18 CD22 is expressed by naive and memory B cells, but not by antigen-secreting cells. Homing of naive IgD+ B cells to PPs was impaired dramatically in mice deficient in CD22 or St6gal1. In contrast, T-cell recruitment was not affected. More studies are needed to determine the precise role of CD22 and its ST6GAL1-dependent carbohydrate addressin ligand in the multistep process of B-cell recognition of PP HEVs, as well as their roles in recruitment of B cells to the gut wall. Human B cells express CD22, and an antibody against glycotopes produced by ST6GAL1 binds to HEVs in human mucosal lymphoid organs.29 Thus, CD22 and its vascular ligand may contribute to B-cell homing to GALT in humans as well.

Homing of Lymphocytes to the Intestinal Epithelium

There are 2 major subsets of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). Conventional or type a IELs, similar to lamina propria T cells (see later), originate from circulating T cells activated in lymphoid organs and imprinted for gut homing using α4β7 and CCR9. Unconventional or type b IELs, in contrast, derive from CD8αβ thymocytes that migrate to the intestinal epithelium and undergo further differentiation into IELs,2 although some type b IELs also may arise extrathymically.30,31 Interestingly, naive CD8αβ recent thymic emigrants already express α4β7 and CCR9 when they leave the thymus, they home directly via the blood to the small intestines without requiring education or imprinting in lymphoid tissues.1 Naive CD4+ T cells also localize to the small intestine epithelium using α4β7, but they do not require CCR9 for this process.2 GPR18 was implicated in localization or accumulation of CD8αα-positive T cells in the intestinal epithelium, but not in their recruitment from the blood.32

Homing of Leukocytes to the Lamina Propria

It has been known for more than 40 years that lymphoblasts from the MLNs, in contrast to small resting lymphocytes, migrate selectively to the intestine lamina propria (reviewed by Butcher and Picker3 and Salmi and Jalkanen5). Upon T-cell priming and activation in the GALT, gut-homing blasts up-regulate integrin α4β7 and CCR9, which direct them to the small intestine lamina propria33,34 (Figure 1). Such induction of specific trafficking programs is termed imprinting, and in MLNs is mediated in part by retinoic acid produced by migratory intestinal conventional DCs35–37 and/or by stromal cells.38

T Cells

The small intestine epithelium produces the chemokine CCL25 (also known as thymus-expressed chemokine), a ligand for the chemokine receptor CCR9, and lamina propria venules express the α4β7 integrin ligand MADCAM1.15,39,40 Lymphocytes that express both α4β7 and CCR9, including lymphoblasts and memory/effector T cells activated in GALT by antigens from the small intestines, are recruited to the small intestine. Homing also involves the β2 integrin lymphocyte function–associated antigen-1 (CD11a/CD18).41 Adoptive cell transfer and intravital microscopy studies have confirmed that small intestine lamina propria T cells, but not spleen T cells, bind to small-intestine microvessels in the lamina propria, and that binding requires integrin α4β7 and MADCAM1.42 Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM1), which selectively binds lymphocytes through integrin α4β1 and mediates lymphocyte homing to non-intestinal sites of chronic inflammation such as in lung, skin and the inflamed central nervous system (CNS), is not normally expressed by intestinal venules, but can be up-regulated on vessels, perhaps particularly in the submucosae, during inflammation.43 Whether this allows recruitment of α4β1+ β7− lymphocytes, which normally are excluded from the gut wall, remains to be determined.

Interestingly, expression of CCL25 decreases from the proximal to the distal small intestine in mice,44 and CCR9-independent mechanisms contribute to homing of T cells to the distal small intestine (shown for effector CD8αβ+ T cells).45 Colon epithelium expresses little CCL25,39,46 few mouse or human colon T cells express CCR9,39,47 and CCR9 is not required for trafficking of T cells to the colon. The large-intestine epithelium, as well as respiratory and salivary gland epithelia, produces the chemokine CCL28 (also known as mucosae-associated epithelial chemokine), which binds to the receptor CCR10. CCR10 mediates localization of plasmablasts to the colon (discussed later), but is not expressed on most colon T cells48 and does not appear to contribute to their recruitment. Instead, CCR10 is expressed preferentially by subsets of skin-homing T cells, mediating their epidermotropism.49 As discussed in detail later, the orphan G-protein–coupled receptor 15 (GPR15) directs T cells to the colon.

CCR6 and its ligand CCL20 also can contribute to localization of T cells to the intestines.50 CCL20 can be induced by inflammation in epithelial and other cells, and is expressed constitutively by the specialized epithelium overlying PP follicles and colon patches. CCR6 is expressed by T-helper (Th) 17 cells, and may help mediate regional localization of these cells in the mouse intestines, especially in inflammation.50 CCR6 and CCL20 contribute significantly to lamina propria T-cell recruitment to the inflamed small-and large-intestine colon, but not in the absence of inflammation.51 CXCR4 and its widely expressed ligand CXCL12 also may participate in lymphocyte localization to the gut.51

Colon tissues from patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) and mice with colitis express higher levels of CCL20 than uninflamed colon tissues.52,53 Moreover, antibodies against CCL20, or desensitization to CCR6, block adhesion of T and B cells to inflamed microvessels in mice with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis.52 These results indicate that CCR6 and CCL20 mediate the recruitment of T cells to the epithelium overlying the PPs and colon patches under homeostatic conditions, and the localization of T cells to the small- and large-intestine lamina propria during inflammation.

T-Regulatory Cells

Like T-effector and memory cells that localize to the intestine, T-regulatory cells (Tregs) that home to the small intestine also express CCR9 and integrin α4β7 in the MLN.54,55 Expression of integrin α4β7 and CCR9 on Tregs is required for induction of oral tolerance to antigen.56,57 Although increased expression of the integrin α4β7 by circulating Tregs correlates with a reduced risk of intestine graft-vs-host disease in humans beings,58 few circulating human Tregs express integrin α4β7, as opposed to cutaneous lymphocyte antigen, which allows them to localize to the skin.59 This leads to the question of whether additional adhesion molecules mediate migration of Tregs to the intestine.

However, it is important to note that Tregs can regulate intestinal responses not only in the gut wall, but also in the GALT, where they can inhibit activation and generation of effector T cells. In lymphopenic mice that develop colitis after transfer of naive (CD45Bhigh) T cells, transfer of CD25+ Tregs leads to resolution of the colitis.60 Tregs require CCR7, but not β7 integrins, to suppress colitis in this model.61,62 Therefore, in this model, Treg homing to the gut wall is not required to prevent colitis. On the other hand, in mice with Citrobacter rodentium–induced colitis, Treg localization to the gut wall reduced inflammation,63 indicating that the suppressive activities of Treg cells and their localization in GALT vs intestinal wall can vary among models. In mice with chronic ileitis, CCR5 appears to contribute to migration of FOXP3+ Tregs (retroviral transduced with murine FoxP3 gene) to inflamed lesions of the distal small intestine.64

As for T-effector and memory T cells, interactions between CCR6 and CCL20 could be important for the migration of Tregs to the inflamed colon; Ccr6−/− Tregs have a reduced ability to enter the inflamed colon and moderate colitis in mice.50,65 Human and mouse Tregs also can express CCR10, implicated in their recruitment to epithelial tissues such as the skin and bile ducts.66 Given the dependence of Treg function on their localization,67,68 further studies of Treg trafficking properties and regulation are warranted.

Role of GPR15 in Colon T-Cell Homing

GPR15 is an orphan G-protein–linked receptor with homology to chemokine receptors. A role for GPR15 in T-cell localization to the colon initially was suggested by a microarray study of tissue-resident lymphocytes, which showed preferential expression of Gpr15 by memory phenotype CD4+ T cells in the colon, compared with those in other tissues (Habtezion et al, unpublished data; and Nguyen et al69). Subsequent studies based on this observation confirmed the ability of GPR15 to mediate T-cell localization to the mouse colon.63,69 GPR15 is important for both regulatory and effector and memory T-cell accumulation in the large intestine, and mediates short-term homing of ex vivo polarized Th17 cells,69 and of GPR15-transduced T cells to the colon.63 Moreover, GPR15-mediated T-effector-cell homing to the colon is required for pathogenesis in the classic CD45RBhigh T-cell transfer model, in which T-effector-cell homing to the colon is critical.69,70 Conversely, in this model, Tregs act in the GALT and not primarily in the lamina propria, thus GPR15 is not required for Treg suppression of disease. On the other hand, GPR15-mediated Treg homing is required for efficient control of gut inflammation in a Citrobacter rodentium–induced colitis model.63

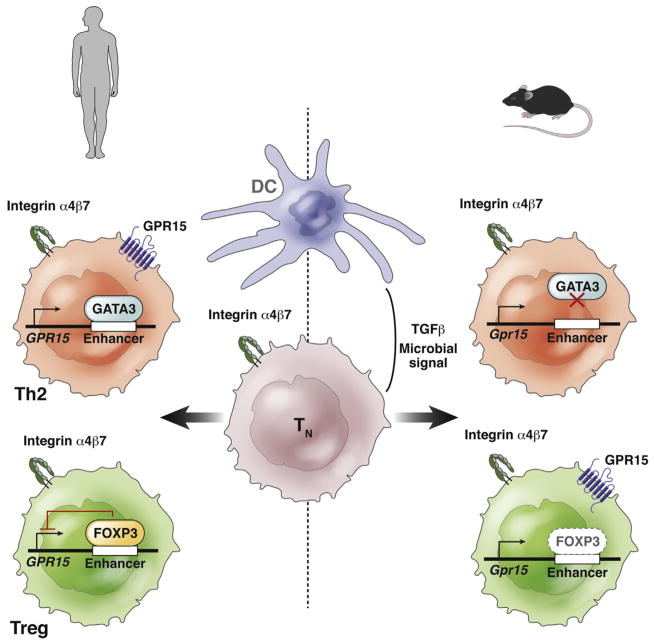

GPR15 expression and function is not limited to colon T cells and their trafficking. In mice, GPR15 is expressed by subsets of CD4+ Treg and CD8+ T cells in other tissues, and emerging studies have suggested that GPR15 may have a broad role in T-cell localization to epithelial surfaces. For example, GPR15 mediates the early recruitment of thymus-derived, dendritic, epidermal T-cell precursors to the epidermis during fetal development in the mouse.71 In humans, an antibody against GPR15 binds diverse subsets of circulating T cells, including many skin-homing and other integrin α4β7-negative memory CD4+ T cells, as well as subsets of gut-homing (α4β7+) memory T cells and subsets of blood (but not colon) CD25+CD127low Tregs (Butcher and Habtezion et al, unpublished data).72 The regulation of GPR15 remains incompletely understood, although transforming growth factor β1 and gut microbiota, but not retinoic acid, can up-regulate its expression during T-cell activation (Figure 2).63 Its physiologic ligand also remains to be determined. Homing of GPR15-expressing T cells to the colon occurs in the absence of microflora,63 so cells of the gut wall, rather than microbiota, are the likely source of GPR15-attracting molecules. We can look forward to future studies of this chemoattractant receptor in intestinal immune biology, and to identification of its physiologic ligand(s).

Figure 2.

Model of the control of T-cell expression of GPR15 in mice and humans. In the model, the colon provides signals (potentially presented by colon-derived DCs in draining lymph nodes) that induce differentiation of TN cells into Th2 or Treg cells and also their expression of α4β7. Additional signals, including transforming growth factor (TGF)β, and products derived directly or indirectly from intestinal microbiota up-regulate GPR15 expression on Th2 cells in humans, but on Tregs (and Th17 cells, not shown) in the mouse. Expression of GPR15 is regulated by transcription factor binding to 3 prime GPR15 enhancer sequences. In human Th2 cells (top left), GATA3, a positive regulator of Th2 cell-specific transcription, binds to enhancer sequences to activate expression of GPR15.69 In human Tregs (bottom left), the transcriptional repressor FOXP3 binds this enhancer region strongly, reducing expression of GPR15 in activated (FOXP3+) Tregs in the normal or inflamed colon. In contrast, altered enhancer sequences in the mouse do not bind GATA3, so that transcription is not activated in mouse Th2 cells (top right), and bind Foxp3 only poorly, allowing expression in Tregs (bottom right). Although other regions of the gene and regulators clearly are involved, the differences in enhancer binding by these important transcriptional regulators likely mediates the differences in GPR15 expression observed in human vs mouse T cells. These differences would affect translation of findings from mouse studies to humans.

Importantly, there are striking differences in the subsets of T cells that express GPR15 in humans compared with mice. As noted earlier, major subsets of blood-borne memory CD4 cells in humans, but not in mouse, express the receptor. In the lamina propria of human colon, effector T cells strongly express GPR15—particularly Th2 cells—but the receptor is not detected on colon-resident FOXP3high Tregs,63,69,72 suggesting a selective role for the receptor in pathogenic vs regulatory cell recruitment to the colon. Indeed, studies of short-term localization of human T-cell subsets injected into the ileocolic arteries of mice found that knockdown of GPR15 inhibited T-effector cell but not Treg homing to the inflamed colon, whereas blocking antibody against integrin α4β7 (vedolizumab) inhibited both T-cell subsets, confirming involvement of specific trafficking mechanisms.72 Together, these independent studies69,72 suggest that GPR15 mediates localization of human T effector cells but not of human Tregs to the inflamed colon. Thus, GPR15 antagonism should be evaluated for the treatment of colitis in patients.

The species-specific differences in GPR15 expression are associated with differences in binding of transcription factors to enhancer sequences of the GPR15 gene.69 Human (but not mouse) Th2 cells express high levels of GPR15, and this correlates with strong binding of the master regulator of Th2 differentiation, transcription factor GATA3, to a downstream enhancer in human Th2 cells, whereas GATA3 does not bind the homologous site in mouse Th2 cells (Figure 2). Moreover, reduced expression of GPR15 by human colon Tregs, which strongly express FOXP3, correlates with stronger binding of transcriptional repressor FOXP3 to the human vs the mouse enhancer sequences.69 These differences in master transcription factor binding to human vs mouse regulatory sequences in the GPR15 gene may underlie the dramatic differences in GPR15 expression by human vs mouse T cells.

Plasma cells

B cells use chemokine receptors to support various stages of their development and function as they move through the follicular microenvironment, develop into memory cells or plasmablasts, and migrate via lymph and blood to tissues for local immune surveillance or for secretion of antibodies. B cells recirculating through or activated in PPs exit in lymph to the MLN, where they can receive further antigenic stimulation in response to migratory intestinal DCs. Exit of B cells from PPs into lymph is regulated by CXCR5 (which promotes their retention), CXCR4, and the G-protein–coupled receptor sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor 1 (which promotes their egress).73 Memory B cells characteristically express CCR6, which can target them to sites of inflammation as discussed for T cells earlier. Memory B cells also show tissue-specific homing receptors, similar to those discussed earlier for T cells: for example, α4β7 is expressed more highly by intestinal memory B cells than by naive B cells, and a subset of α4β7 high memory B cells expresses CCR9. B cells developing into antibody-secreting plasmablasts also are imprinted with gut trafficking programs before their exit from MLN.74,75 Unlike memory B cells, plasmablasts lack CCR6, but in the MLN, IgA plasmablasts up-regulate α4β7 in combination with CCR9 and/or CCR10.76,77 Expression of integrin α4β7 and CCR9 is induced on developing plasmablasts by retinoic acid, just as in T cells,78 and colon patch DCs induce expression of CCR10 on developing plasmablasts.79

As for T cells, selective localization of plasmablasts to the small intestine is mediated predominantly by α4β7/MAD-CAM1 and CCR9/CCL25.80 However, CCR10 and its ligand CCL28 can mediate plasmablast homing to both small and large intestines. CCL28 is a common mucosal chemokine that is expressed highly by epithelial cells in the colon, respiratory tract, salivary glands, and other nonsquamous mucosal epithelia, and at lower levels in the small intestine.48,81 Plasma cells in the human and mouse small-intestine lamina propria express CCR9 and CCR10.48,81,82 Blocking either CCL25 or CCL28 partially prevents small intestinal accumulation of IgA+ cells,81 indicating that CCR9 and CCR10 have overlapping roles in localization of these cells to the small intestine. In contrast, antigen-secreting cells in the colon express CCR10 but not CCR9, and anti-CCL28, but not anti-CCL25, inhibits accumulation of IgA-producing plasma cells in the colon.48,81,82 CCR10 and CCL28 therefore, in conjunction with integrin α4β7, support localization of IgA+ plasmablasts to the colon.48,77,79,81,83 In patients with active colitis, circulating plasmablasts express high levels of integrin α4β7 and CCR10, compared with patients without colitis.84

CCR10 with integrin α4β1 and vascular VCAM1 also mediate localization of integrin α4β7-negative plasmablasts to nonintestinal mucosal sites where CCL28 also is expressed (the respiratory tract, salivary, lacrimal glands, and potentially the genitourinary tract). Expression of a shared mucosal attractant receptor among IgA-secreting cells may facilitate dissemination of immune responses to diverse mucosae, providing a basis for concepts of a common mucosal immune system.85 However, CCR10 cannot fulfill such a unifying role for T-cell responses. Among effector and central memory T cells, CCR10 is almost entirely restricted to integrin α4β1+α4β7− cutaneous lymphocyte antigen+ skin-homing cells (providing T-cell attraction to the CCR10 ligand CCL27, which is expressed on keratinocytes).

Migration of DCs

DCs are potent antigen-presenting cells, specialized for processing and transporting antigens and microenvironmental signals from peripheral sites to draining lymph nodes for presentation to T cells.86–88 In the gastrointestinal tract, DCs continually sample dietary, commensal, and pathogenic microflora antigens. Intestinal DCs are divided into specialized subsets, each of which is characterized and in part defined by their expression of unique trafficking and adhesion receptors, and migratory properties.

Conventional DCs

Expression of CD103 (integrin αE) defines the major conventional DC (cDC) populations in the gut.35,36,89 In combination with β7 integrin, CD103 mediates cellular adhesion to E-cadherin (CDH1), expressed by epithelium. Analogous to its role in CD8+ T cells,90 CD103 expression and activation may regulate retention of DCs in the gut. Expression of CD11b or integrin αM, the α chain of the β2 integrin Mac1, divides these CD103+ cDCs into CD11b− and CD11b+ cDC subsets (recently designated cDC1 and cDC2, respectively).91 Similar subsets populate the human intestinal lamina propria.92 cDC1 express the chemokine receptor XCR1,93 whose ligand XCL1 is expressed by CD8+ T cells. XCR1-mediated attraction to CD8+ T cells may contribute to the specialized ability of cDC1 to cross-present antigens and induce responses in CD8+ T cells.94 cDC1 and cDC2 differ in their expression of receptors for inflammatory chemokines (eg, CCR1 on cDC2 vs CXCR3 on cDC192), which may regulate their microenvironmental position and their interactions with other cells in the context of pathogenic inflammation or infection. cDC1 and cDC2 also express distinct Toll-like receptors, which allows them to sense and respond to different types of microbes; these Toll-like receptors in turn trigger CCR7 up-regulation and migration of the responding cDC subset to draining MLN. cDC2 express CLEC4 family C-type lectins, including CD209 (also known as DC-SIGN [specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin]) in human cells; CD209 supports interactions with activated T cells through ICAM3, and can mediate ICAM2-dependent DC rolling on endothelium. It may contribute to recruitment of blood-borne cDC precursors.95 Human but not mouse circulating and intestinal cDCs express high levels of integrin α4β792; this gut trafficking receptor is down-regulated in developing mouse CD103+ cDCs, as CD103 is up-regulated.96

With antigen capture and processing, cDC1 and cDC2 mature and express CCR7, which mediates their entry into afferent lymphatics and migration to the draining MLN where they prime antigen-specific lymphocytes (Figure 1)36,97,98—a process necessary for mucosal IgA and T-cell immunity (Figure 1).99 Afferent lymphatic endothelium expresses the CCR7 ligand CCL21, which directs mature cDCs into the lymph. Migratory intestinal DCs also are specialized in their ability to process vitamin A to retinoic acid for presentation, along with antigen, to responding T cells.37,100,101 Retinoic acid imprints small-intestine homing properties on T cells activated in the MLN, by inducing expression of integrin α4β7 and CCR9102–104 and suppressing induction of skin-homing receptors.49 The ability of migratory intestinal cDCs to generate retinoic acid also contributes to their tolerogenic function because retinoic acid inhibits effector cell and favors Treg differentiation in the absence of pathogen-associated signals.100,101 Recent studies also have shown that retinoic acid programs intestinal migration of innate lymphoid cell subsets (innate lymphoid cell subsets 1 and 3) via induction of integrin α4β7 and CCR9 in the MLN.105

Subsets of DCs use CCR6 to migrate to the CCL20-expressing subepithelial dome of PPs for antigen sampling from specialized M cells, which are concentrated in the overlying epithelium.106,107 CCR1 interaction with CCL9 also has been implicated in the recruitment of CD11b+ DCs into the subepithelial dome.108

In addition to the well-characterized CD103+ cDCs, which are derived from dedicated bone marrow precursors, the lamina propria contains populations of CD103-negative mononuclear phagocytes that express the chemokine receptor CX3CR1. These include a minor migratory CD103-negative subset of cDCs derived from Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3-dependent bone marrow precursors with a CX3CR1intCCR2+ phenotype, and a major CX3CR1high monocyte-derived population87,109–113 (reviewed by Persson et al112). In healthy intestines, monocyte-derived CXCR3+ cells are predominantly or exclusively resident (nonmigratory) noninflammatory sentinels, but in inflammation recruited monocytes also give rise to CCR7+ migratory T-cell–stimulating antigen-presenting cells that are functional DCs.114

Plasmacytoid DCs

In mice, CCR9 mediates recruitment of plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) to the intraepithelial compartment of the small intestine115 and to the thymus, where they contribute to the transport of peripheral antigens for central tolerance.116 CCR7 contributes to localization of pDCs to organized lymphoid tissues.117 Little is known about the signals that regulate localization of pDCs to the colon. Human pDCs appear to be CCR9 negative (reviewed by Mathan et al,118 and our unpublished observations). Conversely, human but not mouse pDCs express the chemoattractant receptor CMKLR1,119 whose ligand is up-regulated in the inflamed gut.120 Thus, mechanisms of pDC traffic to the human intestine require further investigation, and species differences in DCs as well as T-cell trafficking must be considered when extrapolating preclinical studies to humans.

Gut-Homing Precursors of Intestinal DCs

Intestinal CD103+ cDCs, the predominant populations of cDC in the intestines, derive from circulating bone marrow–derived precursors that home to the gut wall. These include preconventional DCs, which can populate diverse tissues with conventional cDC1 and cDC2 subsets, and preconventional pDCs, which preferentially give rise to plasmacytoid DCs.121,122 Of particular relevance to the intestine, however, is the recent identification of premucosal DC (pre-μDC), a specialized gut-tropic precursor of intestinal DC.86,96 Pre-μDCs are B220+CD11cint α4β7+ precursors that are present in the bone marrow and are particularly abundant in the small-intestine lamina propria and MLNs.96 Pre-μDCs give rise to CD103+ cDC1, cDC2, and α4β7-negative CCR9+ pDCs in vitro and in vivo.

Interestingly, retinoic acid, which as noted earlier programs lymphocyte migration to the intestines, also enhances pre-μDC development in the bone marrow,96 and programs the transcriptional and phenotypic specialization of developing intestinal cDC1 as well as cDC2.123,124 Interestingly, transfused pre-μDCs localize efficiently to the small-intestinal lamina propria,96 even though they do not express CCR9. This localization is inhibited by anti-α4β7 and by anti-MADCAM1, but the chemoattractant pathway involved in their selective recruitment remains unknown. In contrast to pre-μDC, preconventional cDCs express CCR2 but lack dedicated gut-homing receptors; they localize less well to the intestines than pre-μDC, but are more abundant than the gut-tropic precursors in the bone marrow. The relative contribution of these distinct precursor populations to DCs in mucosal vs nonmucosal lymphoid tissues remains to be determined, and may depend not only on the tissue site, but also on the presence or absence of inflammation. Interestingly, however, recent studies have supported a critical role for α4β7 and for MADCAM-1 in reconstitution of intestinal cDCs,125,126 suggesting that the gut-tropic pre-μDCs are important in homeostatic settings. The trafficking receptors on human DC progenitors that direct them to specific intestinal tissues are not yet known.

Monocytes and Neutrophils

Circulating neutrophils and phagocytic monocytes provide the first line of defense against infection and play important roles in wound healing, but they also contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases.127 Histologically, neutrophils are particularly prominent in ulcerative colitis. Myeloid cell recruitment plays a variable role in the pathogenesis of preclinical models of intestinal inflammatory disease, depending on the setting and timing.127 For example, neutrophils are prominent in acute colitis, and inhibition of myeloid cell trafficking or function is highly effective in attenuating colitis in chemically induced models, but not in the CD45RB T-cell transfer model, which is predominantly T-cell mediated. Neutrophils and monocytes largely lack α4β7 and do not express receptors for the constitutive mucosal chemokines CCL25 and CCL28; thus, their recruitment to the intestines is mediated almost exclusively by inflammatory mechanisms (vascular selectins, L-selectin ligands, P selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 [PSGL1], and inflammatory chemokines), similar to the mechanisms they use to migrate to other tissues. The interested reader therefore is referred to recent comprehensive reviews for detailed discussion.128,129

Ecto-Enzyme Vascular Adhesion Protein-1 and the Hyaluronan Receptor CD44

Ecto-enzymes expressed by endothelial cells and lymphocytes also regulate their interactions.130 Among these, vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP1) is of particular interest because it directly binds lymphocytes, and because it is a target of ongoing clinical trials in autoimmune disorders. VAP1 is a cell surface amine oxidase that mediates lymphocyte adhesion to endothelial cells.131 Antibody to VAP1 inhibits binding of CD8 T cells and natural killer cells, but not of CD4 or B cells to HEV in an in vitro assay.132 VAP1 mediates lymphocyte subtype-specific, selectin-independent recognition of vascular endothelium in human lymph nodes.132

In vivo blocking studies have shown that VAP1 is involved in the migration of monocytes and granulocytes to sites of inflammation as well.133,134 The enzyme’s amine oxidase activity can induce expression of E- and P-selectins on endothelial cells,135 and it enhances MADCAM1 on hepatic vessels in a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α-dependent manner, providing a possible mechanism for extraintestinal manifestations of IBD.136 A small-molecule inhibitor of the amine oxidase activity attenuates oxazolone-mediated experimental colitis.137 The role of VAP1 in specific intestine lymphocyte and innate immune cell trafficking and development of IBD, however, requires further study.

Interaction between leukocyte transmembrane glycoprotein CD44 and hyaluronan, expressed by endothelial cells, has been implicated in slowing the rolling of lymphocytes and myeloid cells on endothelium (reviewed by Salmi and Jalkanen,5 DeGrendele et al,138 and McDonald and Kubes139). CD44 also is expressed on intestinal endothelium, and both endothelial and lymphocyte CD44 are implicated in in situ interactions of polarized Th1 and Th2 cells with TNFα-stimulated lamina propria venules. Antibodies to different epitopes of CD44 inhibit binding of human lymphocytes to HEVs in frozen sections of appendix or of synovium and PLNs: HEV binding was not mediated by endothelial hyaluronan, indicating the potential for yet-to-be defined mechanisms and roles for CD44 in intestinal vascular recognition and lymphocyte homing.140 Interestingly, CD44 ligation enhances lymphocyte binding to VAP1, suggesting the potential for CD44 antibodies or physiologic ligation to regulate alternative adhesion pathways.141 The role of CD44-mediated vascular interactions in lymphocyte homing to resting or inflamed intestines, and in intestinal inflammation, deserves further study.

Trafficking Blockade and Intestinal Inflammation

In cotton-top tamarins, which develop spontaneous colitis, as well as in mouse models of T-cell–mediated colitis, administration of antibodies against integrin α4, or specifically against integrin α4β7, reduces inflammation and the severity of colitis.70,142–145 These studies have led to the first clinical applications of antibodies to trafficking receptors for the treatment of IBD (see later).

Studies of chronic ileitis in mice, models of Crohn’s disease, show complex mechanisms of lymphocyte recruitment during chronic small-intestinal inflammation. In the spontaneous SAMP1/Yit model of ileitis, pathogenic CD4 T cells are recruited not only through homeostatic α4β7/MADCAM1 mechanisms, but also through L-selectin. Attenuation of ileitis requires administration of antibodies to MADCAM1 and L-selectin, neither alone was effective.146 L-selectin contributes to leukocyte rolling in a variety of settings: in the ileitis model L-selectin blockade reduced the accumulation of α4β1 high, but not of α4β7 high, cells in the gut wall, consistent with the reported role for VCAM1.147 In Crohn’s disease, inflammation penetrates the full thickness of the involved small-intestine walls, and although MADCAM1 is the predominant α4 integrin ligand in the lamina propria, inflamed vessels in the submucosae (similar to vessels in most nonintestinal environments) express VCAM1. Patients with IBD often have increased expression of the peripheral node addressin (epitopes associated with high-affinity ligands for L-selectin) on vessels in chronically inflamed intestinal tissue, consistent with L-selectin involvement in human disease as well.148 Interestingly, however, intestinal venules in mouse chronic ileitis also express functional PSGL1, thought to mediate the L-selectin–dependent lymphocyte interactions; and neutralization of PSGL1 alone was sufficient to attenuate disease.149 Further complicating matters, these studies suggest the involvement of multiple mechanisms for pathogenic T-cell recruitment. Thus, strategies to target more than one adhesion molecule may offer improved therapeutic efficacy in Crohn’s disease.150 However, the expression patterns of these vascular adhesion receptors in the inflamed small intestine of patients with Crohn’s disease need to be determined.

Studies of the role of CCL25 and CCR9 in intestinal inflammation further highlight opportunities and challenges for therapeutic intervention. In the SAMP1/Yit spontaneous model of ileitis, inhibition of CCR9 or its ligand CCL25 attenuated early disease, but had no effect in later stages in the chronic ileitis model.151 Lack of efficacy in later-stage disease corresponded to a reduction of CCR9+ lymphocytes in the ileum as disease progressed to a chronic state.149 To further complicate matters, the effectiveness of a given intervention may depend on the relative contributions of, and effects on, regulatory vs inflammatory T-cell recruitment to the gut wall: CCR9/CCL25 mediates regulatory as well as effector cell homing to the small intestine, and in a TNFα-driven model of chronic ileitis CCR9 deficiency or anti-CCR9 administration actually exacerbated disease.152 Although effects on tolerogenic CCR9+ pDCs (see later) or other CCR9-expressing cells were not excluded, increased ileitis correlated with reduced regulatory CD4 and/or CD8 T cells in the lamina propria and MLN. The adverse effect of CCR9 neutralization in these studies contrasts with the reported inhibition of early disease, in the same ileitis model, by a small-molecule antagonist of CCR9.153 Together, these pre-clinical studies suggest that CCR9 and CCL25 can contribute to T-cell–mediated pathogenesis in ileitis, but also to regulatory T-cell–mediated disease moderation in the small intestine. The relative effects of trafficking receptor inhibition on pathogenic vs regulatory cell homing and function should be considered in clinical trials.

Blockade of CCL25 in mice with acute or chronic chemically induced colitis, or deletion of CCR9 from host lymphocyte-deficient mice in the CD45RB T-cell transfer model of colitis, also exacerbated large-intestinal disease.154,155 Because CCL25 is poorly expressed in the colon and T-cell homing to the colon is not dependent on CCR9, it will be important to determine whether the adverse effects of CCR9/CCL25 inhibition in these colitis models is mediated by effects on CCR9+ tolerogenic pDCs.

Although the roles of CXCR3 and its ligand CXCL10 in leukocyte trafficking to the colon are not clear, it is of interest that messenger RNAs encoding these molecules increase with the development of colitis in interleukin 10-null mice,156 and that blockade of CXCL10 reduces the severity of colitis in infectious and DSS mouse models of colitis.157,158 CXCR3-deficient mice are resistant to DSS-induced colitis.159 CXCR3 and its ligands CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 are reportedly overexpressed in pediatric and adult patients with IBD.160,161

Clinical Research Findings

A humanized antibody against α4-integrin (natalizumab), which blocks both α4β7/MADCAM1 and α4β1/VCAM1 interactions, is effective for the treatment of Crohn’s disease.162–165 Natalizumab also showed positive results in a limited trial in ulcerative colitis.162 However, pan-α4 inhibitors suppress immunity throughout the body, including in the central nervous system, and prolonged natalizumab therapy was associated with activation of John Cunningham virus in the central nervous system, resulting in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.166 This devastating complication of suppression of systemic immune trafficking has led to an intense interest in more selective inhibitors. Vedolizumab selectively inhibits intestinal lymphocyte homing and has proven effective in ulcerative colitis167 and Crohn’s disease.168,169

An alternative approach is to target the integrin β7 subunit, to inhibit not only binding of integrin α4β7 to MAD-CAM1, but also of integrin αEβ7 integrin αEβ7 (or CD103 and CD18) to epithelial E-cadherin. Integrin αEβ7 also is highly expressed by intestinal DCs.86,92 Antibodies against the β7 subunit therefore might alter DC interactions and functions, and could reduce activation of inflammation-inducing T cells in patients with IBD. In a phase 2 trial, etrolizumab (a humanized rat monoclonal antibody170 against mouse and human integrin β7) enhanced the frequency of clinical remission in patients with ulcerative colitis.171

Future studies should further elucidate the mechanisms by which blocking integrins α4β7 and αEβ7 reduce disease in IBD. In addition to inhibiting lymphocyte access to the intestines, blocking integrin α4β7 or MADCAM1 might reduce the replenishment of intestinal DCs from gut-tropic bone marrow precursors. Inhibitors of integrins α4β7 and αEβ7 are likely to alter interactions among cells in the intestinal epithelium and lamina propria as well. Positive results were reported from a preliminary study of the effects of an antibody against MADCAM1 (PF-00547659) in patients with ulcerative colitis172; the antibody now is being tested in larger trials of patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

The status of chemokine receptors as therapeutic targets recently was reviewed in depth.173 Of particular relevance are efforts to target CCR9, whose ligand CCL25 is up-regulated in the inflamed small intestine of patients with Crohn’s disease.47 An orally administered antagonist of CCR9 (vercirnon, CCX282-B) met secondary end points in a randomized placebo-controlled trial, although primary end points were not met.174 A subsequent trial currently is underway. Eldelumab, a human monoclonal antibody against the chemokine CXCL10 (a CXCR3 ligand), showed a trend toward efficacy in phase 2 clinical trials of patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.175,176

Future Directions

The intestine is a unique environment, in continuous contact with environmental stimuli and antigens. The small and large intestine contain a large number of immune cells, and the colon in particular provides one of the most important mucosal surfaces for host–microbe interactions. These interactions mediate normal metabolic and immune homeostasis in people with a healthy microbiome, but also can contribute to the development of IBD or other extra-intestinal disorders under conditions of dysbiosis. The mechanisms and significance of immune cell subset trafficking to the colon remains particularly understudied. Although many trafficking mechanisms studied are conserved among species, recent findings highlight significant differences between mice and humans in dendritic cell and T-cell trafficking receptor expression and use, with potentially major clinical implications. Nonetheless, the elucidation of intestine-specific immune cell trafficking pathways has provided the first gut-specific therapeutic agent for IBD (vedolizumab); ongoing efforts to define and manipulate gut-homing receptors and vascular addressins are likely to improve our understanding of immune cell subsets in intestinal immune homeostasis and in immune pathologies of the gastrointestinal tract.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R37 AI047822, R01 GM37734, AI093981, and U19 AI090019, and an Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (E.C.B.); by National Institutes of Health grants K08 DK069385 and R03 DK085426 (A.H.); by National Institutes of Health grant R01 AI093981 and an Investigator Career Award from the Arthritis Foundation (H.H.); National Institutes of Health grant DK56339 (Stanford Digestive Disease center); by the VA Palo Alto Health Care System; and by a fellowship under the National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 AI07290 (L.P.N.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- cDC

conventional dendritic cell

- DC

dendritic cell

- DSS

dextran sodium sulfate

- GALT

gut-associated lymphoid tissue

- HEV

high endothelial venule

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- ICAM1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IEL

intraepithelial lymphocyte

- MADCAM1

mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule 1

- MLN

mesenteric lymph node

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- PLN

peripheral lymph node

- PP

Peyer’s patch

- pre-μDC

premucosal dendritic cell

- PSGL1

P selectin glycoprotein ligand 1

- Th

T-helper cell

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- Treg

T-regulatory cell

- VAP1

vascular adhesion protein-1

- VCAM1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Staton TL, Habtezion A, Winslow MM, et al. CD8+ recent thymic emigrants home to and efficiently repopulate the small intestine epithelium. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:482–488. doi: 10.1038/ni1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guy-Grand D, Vassalli P, Eberl G, et al. Origin, trafficking, and intraepithelial fate of gut-tropic T cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1839–1854. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luster AD, Alon R, von Andrian UH. Immune cell migration in inflammation: present and future therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1182–1190. doi: 10.1038/ni1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salmi M, Jalkanen S. Lymphocyte homing to the gut: attraction, adhesion, and commitment. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:100–113. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barreiro O, Sanchez-Madrid F. Molecular basis of leukocyte-endothelium interactions during the inflammatory response. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62:552–562. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)71837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girard JP, Moussion C, Forster R. HEVs, lymphatics and homeostatic immune cell trafficking in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:762–773. doi: 10.1038/nri3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alon R, Feigelson SW. Chemokine-triggered leukocyte arrest: force-regulated bi-directional integrin activation in quantal adhesive contacts. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:670–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Umemoto E, Hayasaka H, Bai Z, et al. Novel regulators of lymphocyte trafficking across high endothelial venules. Crit Rev Immunol. 2011;31:147–169. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v31.i2.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butcher EC. Leukocyte-endothelial cell recognition: three (or more) steps to specificity and diversity. Cell. 1991;67:1033–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laudanna C, Kim JY, Constantin G, et al. Rapid leukocyte integrin activation by chemokines. Immunol Rev. 2002;186:37–46. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Streeter PR, Berg EL, Rouse BT, et al. A tissue-specific endothelial cell molecule involved in lymphocyte homing. Nature. 1988;331:41–46. doi: 10.1038/331041a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruegg C, Postigo AA, Sikorski EE, et al. Role of integrin alpha 4 beta 7/alpha 4 beta P in lymphocyte adherence to fibronectin and VCAM-1 and in homotypic cell clustering. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:179–189. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu MC, Crowe DT, Weissman IL, et al. Cloning and expression of mouse integrin beta p(beta 7): a functional role in Peyer’s patch-specific lymphocyte homing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:8254–8258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berlin C, Berg EL, Briskin MJ, et al. Alpha 4 beta 7 integrin mediates lymphocyte binding to the mucosal vascular addressin MAdCAM-1. Cell. 1993;74:185–195. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90305-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berlin C, Bargatze RF, Campbell JJ, et al. alpha 4 integrins mediate lymphocyte attachment and rolling under physiologic flow. Cell. 1995;80:413–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agace WW, Persson EK. How vitamin A metabolizing dendritic cells are generated in the gut mucosa. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee M, Kiefel H, LaJevic MD, et al. Transcriptional programs of lymphoid tissue capillary and high endothelium reveal control mechanisms for lymphocyte homing. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:982–995. doi: 10.1038/ni.2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okada T, Ngo VN, Ekland EH, et al. Chemokine requirements for B cell entry to lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches. J Exp Med. 2002;196:65–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michie SA, Streeter PR, Bolt PA, et al. The human peripheral lymph node vascular addressin. An inducible endothelial antigen involved in lymphocyte homing. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1688–1698. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bargatze RF, Jutila MA, Butcher EC. Distinct roles of L-selectin and integrins alpha 4 beta 7 and LFA-1 in lymphocyte homing to Peyer’s patch-HEV in situ: the multistep model confirmed and refined. Immunity. 1995;3:99–108. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schippers A, Kochut A, Pabst O, et al. beta7 integrin controls immunogenic and tolerogenic mucosal B cell responses. Clin Immunol. 2012;144:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wyant T, Leach T, Sankoh S, et al. Vedolizumab affects antibody responses to immunisation selectively in the gastrointestinal tract: randomised controlled trial results. Gut. 2015;64:77–83. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mora JR, von Andrian UH. Differentiation and homing of IgA-secreting cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:96–109. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens SK, Weissman IL, Butcher EC. Differences in the migration of B and T lymphocytes: organ-selective localization in vivo and the role of lymphocyte-endothelial cell recognition. J Immunol. 1982;128:844–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanemitsu N, Ebisuno Y, Tanaka T, et al. CXCL13 is an arrest chemokine for B cells in high endothelial venules. Blood. 2005;106:2613–2618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warnock RA, Campbell JJ, Dorf ME, et al. The role of chemokines in the microenvironmental control of T versus B cell arrest in Peyer’s patch high endothelial venules. J Exp Med. 2000;191:77–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warnock RA, Askari S, Butcher EC, et al. Molecular mechanisms of lymphocyte homing to peripheral lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:205–216. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura N, Ohmori K, Miyazaki K, et al. Human B-lymphocytes express alpha2-6-sialylated 6-sulfo-N-acetyllactosamine serving as a preferred ligand for CD22/Siglec-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32200–32207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poussier P, Edouard P, Lee C, et al. Thymus-independent development and negative selection of T cells expressing T cell receptor alpha/beta in the intestinal epithelium: evidence for distinct circulation patterns of gut- and thymus-derived T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1992;176:187–199. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosley RL, Styre D, Klein JR. Differentiation and functional maturation of bone marrow-derived intestinal epithelial T cells expressing membrane T cell receptor in athymic radiation chimeras. J Immunol. 1990;145:1369–1375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Sumida H, Cyster JG. GPR18 is required for a normal CD8alphaalpha intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte compartment. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2351–2359. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell DJ, Kim CH, Butcher EC. Separable effector T cell populations specialized for B cell help or tissue inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:876–881. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agace W. Generation of gut-homing T cells and their localization to the small intestinal mucosa. Immunol Lett. 2010;128:21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Annacker O, Coombes JL, Malmstrom V, et al. Essential role for CD103 in the T cell-mediated regulation of experimental colitis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1051–1061. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Pabst O, et al. Functional specialization of gut CD103+ dendritic cells in the regulation of tissue-selective T cell homing. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1063–1073. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, et al. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammerschmidt SI, Ahrendt M, Bode U, et al. Stromal mesenteric lymph node cells are essential for the generation of gut-homing T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2483–2490. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kunkel EJ, Campbell JJ, Haraldsen G, et al. Lymphocyte CC chemokine receptor 9 and epithelial thymus-expressed chemokine (TECK) expression distinguish the small intestinal immune compartment: epithelial expression of tissue-specific chemokines as an organizing principle in regional immunity. J Exp Med. 2000;192:761–768. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briskin M, Winsor-Hines D, Shyjan A, et al. Human mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 is preferentially expressed in intestinal tract and associated lymphoid tissue. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:97–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamann A, Jablonski-Westrich D, Duijvestijn A, et al. Evidence for an accessory role of LFA-1 in lymphocyte-high endothelium interaction during homing. J Immunol. 1988;140:693–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujimori H, Miura S, Koseki S, et al. Intravital observation of adhesion of lamina propria lymphocytes to microvessels of small intestine in mice. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:734–744. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soriano A, Salas A, Salas A, et al. VCAM-1, but not ICAM-1 or MAdCAM-1, immunoblockade ameliorates DSS-induced colitis in mice. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1541–1551. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stenstad H, Svensson M, Cucak H, et al. Differential homing mechanisms regulate regionalized effector CD8alphabeta+ T cell accumulation within the small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10122–10127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700269104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stenstad H, Ericsson A, Johansson-Lindbom B, et al. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue-primed CD4+ T cells display CCR9-dependent and -independent homing to the small intestine. Blood. 2006;107:3447–3454. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papadakis KA, Prehn J, Nelson V, et al. The role of thymus-expressed chemokine and its receptor CCR9 on lymphocytes in the regional specialization of the mucosal immune system. J Immunol. 2000;165:5069–5076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papadakis KA, Prehn J, Moreno ST, et al. CCR9-positive lymphocytes and thymus-expressed chemokine distinguish small bowel from colonic Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:246–254. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lazarus NH, Kunkel EJ, Johnston B, et al. A common mucosal chemokine (mucosae-associated epithelial chemokine/CCL28) selectively attracts IgA plasmablasts. J Immunol. 2003;170:3799–3805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sigmundsdottir H, Pan J, Debes GF, et al. DCs metabolize sunlight-induced vitamin D3 to ‘program’ T cell attraction to the epidermal chemokine CCL27. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:285–293. doi: 10.1038/ni1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang C, Kang SG, Lee J, et al. The roles of CCR6 in migration of Th17 cells and regulation of effector T-cell balance in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:173–183. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oyama T, Miura S, Watanabe C, et al. CXCL12 and CCL20 play a significant role in mucosal T-lymphocyte adherence to intestinal microvessels in mice. Microcirculation. 2007;14:753–766. doi: 10.1080/10739680701409993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teramoto K, Miura S, Tsuzuki Y, et al. Increased lymphocyte trafficking to colonic microvessels is dependent on MAdCAM-1 and C-C chemokine mLARC/CCL20 in DSS-induced mice colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;139:421–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02716.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaser A, Ludwiczek O, Holzmann S, et al. Increased expression of CCL20 in human inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Immunol. 2004;24:74–85. doi: 10.1023/B:JOCI.0000018066.46279.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siewert C, Menning A, Dudda J, et al. Induction of organ-selective CD4+ regulatory T cell homing. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:978–989. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee JH, Kang SG, Kim CH. FoxP3+ T cells undergo conventional first switch to lymphoid tissue homing receptors in thymus but accelerated second switch to nonlymphoid tissue homing receptors in secondary lymphoid tissues. J Immunol. 2007;178:301–311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cassani B, Villablanca EJ, Quintana FJ, et al. Gut-tropic T cells that express integrin alpha4beta7 and CCR9 are required for induction of oral immune tolerance in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2109–2118. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hadis U, Wahl B, Schulz O, et al. Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria. Immunity. 2011;34:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Engelhardt BG, Jagasia M, Savani BN, et al. Regulatory T cell expression of CLA or alpha(4)beta(7) and skin or gut acute GVHD outcomes. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:436–442. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iellem A, Colantonio L, D’Ambrosio D. Skin-versus gut-skewed homing receptor expression and intrinsic CCR4 expression on human peripheral blood CD4+CD25+ suppressor T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1488–1496. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mottet C, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Cutting edge: cure of colitis by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3939–3943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schneider MA, Meingassner JG, Lipp M, et al. CCR7 is required for the in vivo function of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:735–745. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Denning TL, Kim G, Kronenberg M. Cutting edge: CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells impaired for intestinal homing can prevent colitis. J Immunol. 2005;174:7487–7491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim SV, Xiang WV, Kwak C, et al. GPR15-mediated homing controls immune homeostasis in the large intestine mucosa. Science. 2013;340:1456–1459. doi: 10.1126/science.1237013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang SG, Piniecki RJ, Hogenesch H, et al. Identification of a chemokine network that recruits FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells into chronically inflamed intestine. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:966–981. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kitamura K, Farber JM, Kelsall BL. CCR6 marks regulatory T cells as a colon-tropic, IL-10-producing phenotype. J Immunol. 2010;185:3295–3304. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eksteen B, Miles A, Curbishley SM, et al. Epithelial inflammation is associated with CCL28 production and the recruitment of regulatory T cells expressing CCR10. J Immunol. 2006;177:593–603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huehn J, Hamann A. Homing to suppress: address codes for Treg migration. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:632–636. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Campbell DJ, Koch MA. Phenotypical and functional specialization of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:119–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nguyen LP, Pan J, Dinh TT, et al. Role and species-specific expression of colon T cell homing receptor GPR15 in colitis. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:207–213. doi: 10.1038/ni.3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Picarella D, Hurlbut P, Rottman J, et al. Monoclonal antibodies specific for beta 7 integrin and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) reduce inflammation in the colon of scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:2099–2106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lahl K, Sweere J, Pan J, et al. Orphan chemoattractant receptor GPR15 mediates dendritic epidermal T-cell recruitment to the skin. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:2577–2581. doi: 10.1002/eji.201444628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fischer A, Zundler S, Atreya R, et al. Differential effects of alpha4beta7 and GPR15 on homing of effector and regulatory T cells from patients with UC to the inflamed gut in vivo. Gut. 2015 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310022. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schmidt TH, Bannard O, Gray EE, et al. CXCR4 promotes B cell egress from Peyer’s patches. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1099–1107. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Youngman KR, Franco MA, Kuklin NA, et al. Correlation of tissue distribution, developmental phenotype, and intestinal homing receptor expression of antigen-specific B cells during the murine anti-rotavirus immune response. J Immunol. 2002;168:2173–2181. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kunkel EJ, Butcher EC. Plasma-cell homing. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nri1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bowman EP, Kuklin NA, Youngman KR, et al. The intestinal chemokine thymus-expressed chemokine (CCL25) attracts IgA antibody-secreting cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:269–275. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu S, Yang K, Yang J, et al. Critical roles of chemokine receptor CCR10 in regulating memory IgA responses in intestines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E1035–E1044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100156108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mora JR, von Andrian UH. Role of retinoic acid in the imprinting of gut-homing IgA-secreting cells. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Masahata K, Umemoto E, Kayama H, et al. Generation of colonic IgA-secreting cells in the caecal patch. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3704. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pabst O, Ohl L, Wendland M, et al. Chemokine receptor CCR9 contributes to the localization of plasma cells to the small intestine. J Exp Med. 2004;199:411–416. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hieshima K, Kawasaki Y, Hanamoto H, et al. CC chemokine ligands 25 and 28 play essential roles in intestinal extravasation of IgA antibody-secreting cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:3668–3675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kunkel EJ, Kim CH, Lazarus NH, et al. CCR10 expression is a common feature of circulating and mucosal epithelial tissue IgA Ab-secreting cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1001–1010. doi: 10.1172/JCI17244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Feng N, Jaimes MC, Lazarus NH, et al. Redundant role of chemokines CCL25/TECK and CCL28/MEC in IgA+ plasmablast recruitment to the intestinal lamina propria after rotavirus infection. J Immunol. 2006;176:5749–5759. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tarlton NJ, Green CM, Lazarus NH, et al. Plasmablast frequency and trafficking receptor expression are altered in pediatric ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2381–2391. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McDermott MR, Bienenstock J. Evidence for a common mucosal immunologic system. I. Migration of B immunoblasts into intestinal, respiratory, and genital tissues. J Immunol. 1979;122:1892–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bekiaris V, Persson EK, Agace WW. Intestinal dendritic cells in the regulation of mucosal immunity. Immunol Rev. 2014;260:86–101. doi: 10.1111/imr.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cerovic V, Houston SA, Scott CL, et al. Intestinal CD103(−) dendritic cells migrate in lymph and prime effector T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:104–113. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu LM, MacPherson GG. Antigen acquisition by dendritic cells: intestinal dendritic cells acquire antigen administered orally and can prime naive T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1299–1307. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kilshaw PJ. Expression of the mucosal T cell integrin alpha M290 beta 7 by a major subpopulation of dendritic cells in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:3365–3368. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cepek KL, Shaw SK, Parker CM, et al. Adhesion between epithelial cells and T lymphocytes mediated by E-cadherin and the alpha E beta 7 integrin. Nature. 1994;372:190–193. doi: 10.1038/372190a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guilliams M, Ginhoux F, Jakubzick C, et al. Dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages: a unified nomenclature based on ontogeny. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:571–578. doi: 10.1038/nri3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Watchmaker PB, Lahl K, Lee M, et al. Comparative transcriptional and functional profiling defines conserved programs of intestinal DC differentiation in humans and mice. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:98–108. doi: 10.1038/ni.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Crozat K, Guiton R, Contreras V, et al. The XC chemokine receptor 1 is a conserved selective marker of mammalian cells homologous to mouse CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1283–1292. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dorner BG, Dorner MB, Zhou X, et al. Selective expression of the chemokine receptor XCR1 on cross-presenting dendritic cells determines cooperation with CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;31:823–833. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Geijtenbeek TB, Krooshoop DJ, Bleijs DA, et al. DC-SIGN-ICAM-2 interaction mediates dendritic cell trafficking. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:353–357. doi: 10.1038/79815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zeng R, Oderup C, Yuan R, et al. Retinoic acid regulates the development of a gut-homing precursor for intestinal dendritic cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:847–856. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Worbs T, Bode U, Yan S, et al. Oral tolerance originates in the intestinal immune system and relies on antigen carriage by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jang MH, Sougawa N, Tanaka T, et al. CCR7 is critically important for migration of dendritic cells in intestinal lamina propria to mesenteric lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2006;176:803–810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee AY, Chang SY, Kim JI, et al. Dendritic cells in colonic patches and iliac lymph nodes are essential in mucosal IgA induction following intrarectal administration via CCR7 interaction. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1127–1137. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, et al. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mora JR, Bono MR, Manjunath N, et al. Selective imprinting of gut-homing T cells by Peyer’s patch dendritic cells. Nature. 2003;424:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stagg AJ, Kamm MA, Knight SC. Intestinal dendritic cells increase T cell expression of alpha4beta7 integrin. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:1445–1454. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1445::AID-IMMU1445>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Johansson-Lindbom B, Svensson M, Wurbel MA, et al. Selective generation of gut tropic T cells in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT): requirement for GALT dendritic cells and adjuvant. J Exp Med. 2003;198:963–969. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim MH, Taparowsky EJ, Kim CH. Retinoic acid differentially regulates the migration of innate lymphoid cell subsets to the gut. Immunity. 2015;43:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Niess JH, Zammit DJ, et al. CCR6-mediated dendritic cell activation of pathogen-specific T cells in Peyer’s patches. Immunity. 2006;24:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cook DN, Prosser DM, Forster R, et al. CCR6 mediates dendritic cell localization, lymphocyte homeostasis, and immune responses in mucosal tissue. Immunity. 2000;12:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhao X, Sato A, Dela Cruz CS, et al. CCL9 is secreted by the follicle-associated epithelium and recruits dome region Peyer’s patch CD11b+ dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2797–2803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Satpathy AT, Kc W, Albring JC, et al. Zbtb46 expression distinguishes classical dendritic cells and their committed progenitors from other immune lineages. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1135–1152. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Varol C, Vallon-Eberhard A, Elinav E, et al. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31:502–512. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Helft J, et al. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity. 2009;31:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Persson EK, Scott CL, Mowat AM, et al. Dendritic cell subsets in the intestinal lamina propria: ontogeny and function. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:3098–3107. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Scott CL, Bain CC, Wright PB, et al. CCR2(+)CD103(−) intestinal dendritic cells develop from DC-committed precursors and induce interleukin-17 production by T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:327–339. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wendland M, Czeloth N, Mach N, et al. CCR9 is a homing receptor for plasmacytoid dendritic cells to the small intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6347–6352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609180104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hadeiba H, Lahl K, Edalati A, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells transport peripheral antigens to the thymus to promote central tolerance. Immunity. 2012;36:438–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Seth S, Oberdorfer L, Hyde R, et al. CCR7 essentially contributes to the homing of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to lymph nodes under steady-state as well as inflammatory conditions. J Immunol. 2011;186:3364–3372. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]