Abstract

Two structural isomers of the heptadentate chelator DO3Ala were synthesized, with carboxymethyl groups at either the 1,4- or 1,7-positions of the cyclen macrocycle. To interrogate the relaxivity under different rotatational dynamics regimes, the pendant primary amine was coupled to ibuprofen to enable binding to serum albumin. These chelators 6a and 6b form bis(aqua) ternary complexes with Gd(III) or Tb(III) as estimated from relaxivity measurements or luminescence lifetime measurements in water. The relaxivity of [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] was measured in the presence and absence of coordinating anions prevalent in vivo such as phosphate, lactate, and bicarbonate and compared with data attained for the q=2 complex [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2]. We found that relaxivity was reduced through formation of ternary complexes with lactate and bicarbonate, albeit to a lesser degree then the relaxivity of Gd(DO3A). In presence of 100 fold excess phosphate, relaxivity was slightly increased and typical for q=2 complexes of this size (8.3 mM-1s -1 and 9.5 mM-1s -1 respectively at 37 °C, 60 MHz). Relaxivity for the complexes in presence of HSA corresponded well to relaxivity obtained for complexes with reduced access for inner-sphere water (13.5 and 12.7 mM-1s-1 at 37 °C, 60 MHz). Mean water residency time at 37 °C was determined using temperature dependent 17O-T2 measurements at 11.7T and calculated to be 310τM = 23 ± 1 ns for both structural isomers. Kinetic inertness under forcing conditions (pH 3, competing DTPA ligand) was found to be comparable to [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)]. Over all, we found that replacement of one of the acetate arms of DO3A with an amino-propionate arm does not significantly alter the relaxometric and kinetic inertness properties of the corresponding Gd complexes, however it does provide access to easily functionalizable q=2 derivatives.

Keywords: Gadolinium, MRI contrast agents, Relaxivity, Hydration number

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has established itself as one of the key diagnostic techniques in modern radiology. The clinical utility of MR imaging probes (contrast agents) is undisputed. At our institution, just over 50% of all MRI procedures employ a contrast agent. The majority of T1 contrast agents (capable of shortening longitudinal relaxation time of water molecules) are simple, water-soluble, ternary gadolinium(III) complexes with Gd(III) coordinated by an octadentate polyaminocarboxylato ligand and an aqua co-ligand.1, 2 These first generation agents however have water-relaxation properties (relaxivity) that can be greatly improved upon. Relaxivity, r1, is defined as the change in the relaxation rate (R1 = 1/T1) of solvent water upon addition of the probe and normalized to the concentration of metal ion. There are a number of parameters that affect relaxation: hydration (the number of water molecules in the first and 2nd coordination spheres and the Gd-H distance for these waters), water exchange kinetics, and a correlation time that describes the fluctuating magnetic dipole created by the paramagnetic ion (this fluctuating dipole can be a result of rotational motion, electron relaxation, or rapid water exchange). Maximum relaxivity can be achieved at a given magnetic field when the overall correlation time equals the inverse of the Larmor frequency.

There has been considerable effort to optimize these molecular parameters through rational complex design. Water exchange kinetics can be exquisitely tuned by changing the donor groups on the co-ligand or by steric crowding.3-6 Rotational dynamics can be modulated by changing the molecular size, either by covalent7, 8 9, 10 or noncovalent modification.11-14 Control of internal motion is also paramount to optimizing relaxivity and elegant strategies have been elaborated to this end.15-17 Relaxivity is also directly proportional to the number of inner-sphere water ligands (q) and to the number and residency time of second-sphere water molecules.18 Increasing q is challenging because these complexes tend to be more labile with respect to Gd(III) dissociation,19 and because of susceptibility to water ligand displacement by coordinating anions.20 However since increasing q provides a directly proportional relaxivity boost across all magnetic field strengths, this has motivated us,21-24 and others,10, 25-31 to repeatedly revisit the challenge of increasing q without considerable loss of kinetic inertness of the complex. These endeavors however resulted in only limited success.

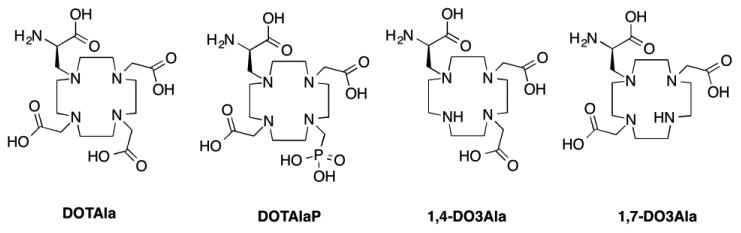

We recently reported the single amino acid chelate Gd(DOTAla) as a modular reagent to construct imaging probes with defined dynamics (Figure 1).32, 33 The DOTAla framework offers great synthetic flexibility via solid- or solution phase peptide synthesis. When the propionate group is converted to an amide in a peptide-like structure, its carbonyl amide O donor coordinates Gd(III) and anchors the chelate to peptide backbone via two points of attachment. In this way the internal motion of the chelate is restricted. We successfully built multimeric structures based on this modular complex that would approximate intermediate rotational correlation times best suited to optimal relaxivity at high magnetic fields. The modular nature of Gd(DOTAla) as an amino acid derivative also lends itself to the design of protein-targeted contrast agents.33 More recently we have explored the effect of changing donor groups on the chelate. By replacing one of the acetate arms of DOTAla with a phosphonate (Figure 1), the water exchange rate can be increased to the point where exchange becomes the correlation time dominating relaxation. One of these Gd(DOTAlaP) derivatives showed exceptionally high relaxivity at high field when bound to serum albumin in contrast to most of the albumin binding probes which tend to have low relaxivity at high fields.34

Figure 1. Structures of DOTAla, DOTAlaP and DO3Ala derivatives.

Here, we sought to further explore the versatility of DOTAla by furnishing the derivative DO3Ala. The heptadentate ligand provides an additional entry point for a second water molecule into the coordination sphere, which theoretically should result in a 100% increase of inner sphere relaxivity. We hypothesized that the propionate arm of DO3Ala would provide greater steric bulk to the lanthanide coordination sphere when compared with conventional DO3A derivatives, preventing formation of ternary complexes with coordinating anions while also avoiding the binding of protein side chains.

In this study we sought to address the following questions: (i) How does the removal of one of the acetate donors in DOTAla impact hydration number and water exchange kinetics, and subsequently relaxivity? (ii) Is there a measurable difference between the 1,4- and the 1,7-isomer (with respect to the amino-propionate arm) in terms of hydration number, water exchange kinetics, relaxivity and Gd(III) dissociation kinetics? (iii) How are these properties altered when the Gd(DO3Ala) derivatives are bound to serum albumin? (iv) How susceptible are Gd(DO3Ala) derivatives to formation of ternary complexes with coordinating anions such as lactate and bicarbonate? (v) How does removal of one of the coordinating acetate arms of Gd(DOTAla) affect kinetic inertness with respect to Gd(III) dissociation under forcing conditions?

We synthesized two isomers of the heptadentate DO3Ala ligand by altering the previously established DOTAla synthesis.32 Both isomers were conjugated to ibuprofen in order to provide HSA-binding capability and compare relaxivity under fast and slow rotational dynamics regimes. The Gd(III) complexes were prepared and characterized by measuring relaxivity in presence of different coordinating anions, water exchange kinetics, albumin binding, and Gd(III) dissociation kinetics. Tb(III) complexes were also synthesized and luminescence lifetime measurements were performed to quantify the hydration number of these complexes.

Experimental Procedures

General materials and methods

1H, 13C, 17O, and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 11.7 T NMR system equipped with a 5 mm broadband probe. Spectra were referenced to internal standards (TMS for 1H and 13C, phosphoric acid for 31P). HPLC purification of intermediates was performed on a Rainin, Dynamax (Phenomenex C18 column: 250 mm × 21.2mm, 10 micron) using Method A: 0.1% TFA in water with a gradient of 5 – 95% (0.1% TFA in MeCN) over 20 min, 15 mL/min flow rate. HPLC purity analyses (both UV and MS detection) were carried out on an Agilent 1100 system (Phenomenex Luna C18(2) column: 100 mm × 2 mm, 0.8 mL/min flow rate) with UV detection at 220, 254, and 280 nm and +ESI using the following methods. Method B: solvent A = H2O, 0.1% TFA, solvent B = MeCN, 0.1% TFA. 5 – 95% B over 15 min. The synthesis of ligands was carried out as shown in Scheme 1. Chemicals were supplied by Aldrich Chemical Co., Inc., and were used without further purification. Solvents (HPLC grade) were purchased from various commercial suppliers and used as received. Compound 1 was synthesized as described previously.32 Ibuprofen-NHS was synthesized as described previously.35 Synthesis and complexation of ligand 7 has been described previously.33

Benzyl(R)-3-(7-benzyl-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecan-1-yl)-2-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino) propanoate (2a)/ Benzyl (R)-3-(4-benzyl-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecan-1-yl)-2-(((benzyloxy) carbonyl)amino)propanoate (2b). 1 (0.342g, 0.7 mmol), was dissolved in MeCN (20 mL) and K2CO3 (0.4g, 4 equiv) was added. Benzylbromide (0.096g, 0.56 mmol, 0.8 equiv) was added dropwise to the reaction and the mixture was allowed to stir for 16 hours at room temperature. H2O (2 mL) was added to prevent overalkylation while the crude mixture is concentrated during the solvent reduction. The residual product was purified using preparative HPLC, method A, with the products 2a/2b (0.305g, 0.53 mmol, 95% yield with regard of added benzylbromide) eluting at 10.5 mins. Fractions containing the products were collected, pooled and the solvent was removed to afford the product as a colorless oil. 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz, ppm): 7.6-7.3 (m, br, 15H), 5.23-4.86 (m, 9H), 3.55-2.93 (m, 16H). LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C33H44N5O4: 574.2 Found: 574.4 [M+H]+, Rt = 6.4 min (Method B).

di-tert-butyl 2,2′-(4-benzyl-10-(3-(benzyloxy)-2-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-oxopropyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,7-diyl)(R)-diacetate (3a)/ di-tert-butyl 2,2′-(7-benzyl-10-(3-(benzyloxy)-2-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-oxopropyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4-diyl)(R)-diacetate (3b). 2 (0.05g, 0.087mmol), K2CO3 (0.04g, 0.262 mmol, 3 equiv.) and tert-butylbromoacetate (0.034g, 25 μL, 0.174 mmol) were dissolved in MeCN (25 mL). The reaction was monitored using analytical HPLC and found to be complete after 1.5h of stirring at room temperature. H2O (1 mL) was added and the majority of the solvent was reduced in vacuo. The crude mixture was purified using preparative HPLC (method A). 3a and 3b were isolated as separate product peaks, eluting at 13 min (3a) and 13.6 min (3b) respectively. The fractions were pooled and lyophilized to afford the two isomers as white solids, in an approximate 2:1 product ratio. 3a (0.025g, 0.031 mmol, 36% purified yield). 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz, ppm): 7.55-7.30 (m, br, 15H), 5.20-4.2 (m, 4H), 4.31-4.05 (m, 4H), 3.84-2.91 (m, 18H), 1.49 (s, 18H). LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C45H64N5O8: 802.5 Found: 802.4 [M+H]+, Rt = 8.6 min (Method C). 3b (0.012g, 0.015 mmol, 18% purified yield). 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz, ppm): 7.55-7.33 (m, br, 15H), 5.23-4.32 (m, 4H), 4.31-4.05 (m, 4H), 3.80-2.81 (m, 18H), 1.49 (s, 18H). LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C45H64N5O8: 802.5 Found: 802.4 [M+H]+, Rt = 8.6 min (Method B).

(R)-2-amino-3-(4,10-bis(2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecan-1-yl)propanoic acid (4a). 3a (0.025g, 0.031 mmol) was dissolved in MeOH (8 mL). Pd/C (10 % w/v, 0.02g) was added and the flask was sealed with a septum and filled with N2. The flask was charged with H2 (1 atm, balloon) and the reaction was stirred for 3 hours, until the reaction was complete as indicated by analytical HPLC. Pd/C was filtered off and the filtrate was collected and the solvent evaporated to afford the product as a colorless oil (0.014g, 0.028 mmol, 89% yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): 8.38 (m, br, 4H, NH), 4.11 (s, 1H), 3.37-2.62 (m, 22H), 1.42 (s, 18H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): 161.7, 161.4, 82.3, 54.2-50.1 (br), 27.9. LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C23H46N5O6: 488.3 Found: 488.3 [M+H]+, Rt = 4.1 min (Method B).

(R)-2-amino-3-(4,7-bis(2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecan-1-yl)propanoic acid (4b). The removal of the Bn and Cbz protective groups from 4b (0.012g, 0.015 mmol) was carried out analogous to the reaction for 4a. 4b was isolated as a colorless oil (0.006g, 0.012 mmol, 80% yield). 1H-NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz, ppm): 3.43-2.80 (m, 23H), 1.46 (s, 9H), 1.29 (s, 9H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): 162.2, 161.7, 85.3, 56.2-52.1 (br), 29.7, 27.9. LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C23H46N5O6: 488.3 Found: 488.3 [M+H]+, Rt = 4.7 min (Method B).

(2R)-3-(4,10-bis(2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecan-1-yl)-2-(2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propanamido)propanoic acid (5a). 4a (0.023g, 0.048 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (5 mL) together with Ibuprofen-NHS35 (0.016g, 0.052 mmol) and DIPEA (7 μL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 48 hours, followed by purification of the product using preparative HPLC (method A). The product 5a elutes at 11.3 minutes. Fractions containing the product are collected, pooled and lyophilized to afford 5a as a white powder (0.004g, 0.006 mmol, 12.5 % purified yield). 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz, ppm): 8.38 (s, br, 1H), 7.27-7.11 (dd, 4H), 4.86-4.19 (m, 4H), 3.68-2.93 (m, 16H), 2.45 (m, br, 4H), 1.85 (s, 1H), 1.52-1.37 (s, 25H), 0.90 (s, 6H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): 172.9, 162.3, 140.4, 128.9, 127.0, 126.9, 81.5,54.8-58.6,45.5-42.5, 30.0, 27.1, 26.7, 21.3, 17.2. LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C36H62N5O7: 676.5 Found: 676.4 [M+H]+, Rt = 8.0 min (Method B).

(2R)-3-(4,7-bis(2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecan-1-yl)-2-(2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propanamido)propanoic acid (5b). 5b was synthesized in analogous fashion to 5a, but with 4b as the starting material. 5b was also isolated as a white powder (0.004g, 0.006 mmol, 12.5 % purified yield). 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz, ppm): 7.30-7.12 (dd, 4H), 3.74-3.09 (m, 24H), 2.47 (m, 2H), 1.85 (m, 1H), 1.84-1.47 (s, 20H), 0.89 (s, 6H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): 171.5, 160.2, 140.5, 129.2, 127.0, 82.5, 47.5-44.6, 30.0, 27.0, 21.3, 17.3. LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C36H62N5O7: 676.5 Found: 676.4 [M+H]+, Rt = 8.3 min (Method B).

2,2′-(4-((2R)-2-carboxy-2-(2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propanamido)ethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclo- dodecane-1,7-diyl)diacetic acid (6a). 5a (0.004g, 0.006 mmol) was dissolved in a 2:1 mixture of TFA and DCM (3 mL) and stirred for 16 hours at room temperature. After reaction monitoring via HPLC revealed full conversion of the starting material, the solvent was removed in vacuo and the oily product 6a (0.003g, 0.005 mmol) was redissolved in H2O and lyophilized to afford the product as a white powder. 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz, ppm): 7.17-6.99 (dd, 4H), 4.60-4.46 (m, br, 2H), 3.64-2.92 (m, 23H), 2.34 (m, 2H), 1.75 (m, 1H), 1.50-1.19 (m, 5H), 0.79 (s, 6H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): 175.2, 173.5, 172.9, 168.3, 161.5 140.4, 138.4, 117.8, 115.5, 55.4-42.2, 30.1, 29.3, 21.3. 17.5. LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C28H46N5O7: 564.3 Found: 564.2 [M+H]+, Rt = 6.3 min (Method B).

6b (0.002g, 0.003 mmol) was synthesized the same way as 6a. 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz, ppm): 7.17-7.01 (dd, 4H), 4.76 (s, br, 1H), 3.84-2.55 (m, 23H), 2.35 (m, 2H), 1.74 (m, 1H), 1.38-1.19 (s, 5H), 0.78 (s, 6H). 13C-NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz, ppm): 174.2, 173.8, 161.2, 140.4, 138.4, 129.1, 126.9, 117.8, 115.5, 53.4-44.6, 30.1, 29.3, 21.3, 17.3. LC-ESI-MS: calcd. for C28H46N5O7: 564.3 Found: 564.2 [M+H]+, Rt = 6.6 min (Method B).

Lanthanide complexes

General synthesis protocol for lanthanide complexes

The ligand was dissolved in H2O (1 mL). An amount of a stock solution containing LnCl3· 6H2O (0.95 equiv based on the ligand weight) was added to the ligand solution under monitoring of the pH. The pH was adjusted to 7 using a 0.1 M NaOH solution. The lightly cloudy solution was filtered and lyophilized to afford the corresponding lanthanide complex as an off-white powder. The purity of the complex was assessed using LC–MS; the presence of free lanthanide ion was excluded using the xylenol orange test. LC-ESI-MS: [Gd(6a)] calcd. for C28H43GdN5O7: 719.2. Found 719.1. [M+H]+. Rt = 6.2 min (Method B). [Gd(6b)] calcd. for C28H43GdN5O7: 719.2. Found 719.1. [M+H]+. Rt = 6.5 min (Method B). [Tb(6a)] C28H43TbN5O7 calcd. 720.2 Found 720.1 [M+H]+. Rt = 6.0 min (Method B). [Tb(6b)] C28H43TbN5O7 calcd. 720.2 Found 720.1 [M+H]+. Rt = 6.3 min (Method B).

Relaxivity measurements

Longitudinal relaxation times T1, were measured on Bruker Minispecs mq20 (20 MHz) and mq60 (60 MHz) using an inversion recovery method with 10 inversion time values ranging from 0.1 × T1 to 5 × T1. Relaxivity in the absence of HSA was calculated from a linear plot of 3 different concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 0.4 mM versus the corresponding inverse relaxation times. The temperature was controlled at 37 °C. Samples with HSA were prepared in a 4.5% w/v solution of HSA (0.66 mM) at concentrations of 0.02 to 0.05 mM.

HSA binding

In order to measure HSA binding of the complexes, a 0.1 mM solution (determined by ICP-MS) of the Gd complex in 4.5% w/v HSA was prepared and pipetted into a Ultrafree-MC Microcentrifuge Filter (NMWL 5,000 Da, PLCC, Millipore). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and subsequently centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. Binding was determined by measurement of Gd content in the filtrate by ICP-MS. % bound = ([initial] – [filtrate])/[initial].

Luminescence

Luminescence lifetime measurements of Tb complexes in H2O and D2O were performed on a Hitachi f-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer. Concentrations of the samples were 0.4 - 1 mM. For the measurements in D2O, the complexes were first dissolved in D2O (99.98% D), lyophilized, and dissolved in D2O again to reduce the amount of residual HDO. Measurements were taken with the following settings: Excitation at 270 nm (Tb) emission at 550 nm, 30 replicates, 0.04 ms temporal resolution (0–20 ms), PMT voltage = 400 V. Lifetimes were obtained from monoexponential fits of the data using Igor Pro software (Version 6.0, Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA).

17O NMR of Gd complexes for determination of τM

17O NMR measurements of solutions were performed at 11.7T on 350 μL samples contained in 5 mm standard NMR tubes on a Varian spectrometer. Temperature was regulated by airflow controlled by a Varian VT unit. H217O transverse relaxation times of a > 2 mM solution of all Gd complexes (pH 7.4, 10 mM PBS buffer) were measured using a CPMG sequence. The exact concentration of the sample was determined by ICP-MS. Reduced relaxation rates, 1/T2r were calculated from the difference of 1/T2 between the sample and the water blank, and then divided by the mole fraction of coordinated water, assuming q = 2. The temperature dependence of 1/T2r was fit to a 4-parameter model as previously described.36 The 17O hyperfine-coupling constant of coordinated water ligands, A/(x00127), was fixed to 3.8 × 106 rad/s.37

Measurement of Kinetic Inertness

Stock solutions of MS-325-L (the ligand of the MS-325 complex),38 [Gd(6a)(H2O)2], [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] and [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2] were prepared. MS-325-L was added to solutions of the Gd complexes in pH 3 water (adjusted using 0.1 mM NaOH) and incubated at 37 °C. The final concentrations of the Gd complexes and MS-325-L were 0.1 mM. A 10 μL aliquot was removed for HPLC analysis and analyzed at time points 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 2, 2.25, 2.5 and 15 h, while the remainder of the solution was incubated at 37 °C.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

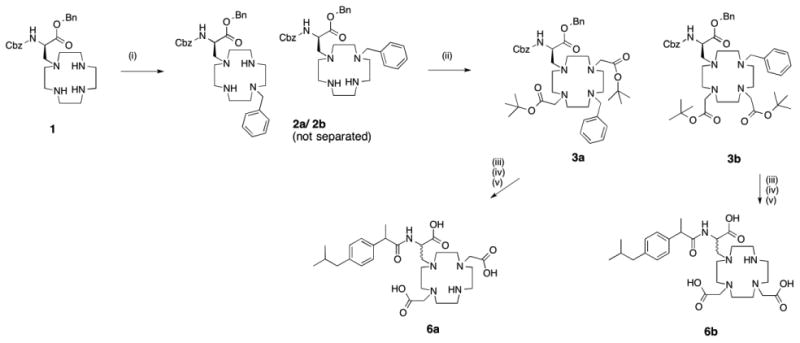

We synthesized 1,4-DO3Ala-Ibu and 1,7-DO3Ala-Ibu using a similar reaction pathway as DOTAla. Benzyl 2-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-(1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecan-1-yl)propanoate, 1, represents an intermediate common to DO3Ala (Figure 2).32 Intermediate 1 was benzylated under alkylating conditions and the resulting mono-benzyl derivatives 2a and 2b were isolated as a mixture using preparative HPLC. Alkylation with tert-butyl-bromoacetate in acetonitrile results in formation of the isomers 3a and 3b, which can be separated by preparative HPLC, with a ratio of 2:1 in favor of the 1,7-isomer. While these isomers are not readily distinguishable by NMR at this stage, after debenzylation the symmetry of 4a versus the asymmetry of 4b is apparent from the 1H- and 13C NMR resonances of the tert-butyl groups. To introduce the ibuprofen moiety, we first attempted a conventional HATU/DIPEA coupling as in previous syntheses,33, 34 but the desired product could not be isolated because intramolecular macrocyclization appears to be a strongly thermodynamically favored product. We instead synthesized NHS-activated ibuprofen, which, when mixed with 4a/4b in presence of 2 equivalents of DIPEA base, affords the products 5a/5b after 48 hours stirring at room temperature and subsequent preparative HPLC purification. The tert-butyl ester protective groups are then removed using an acid catalyzed deprotection reaction with trifluoroacetic acid in dichloromethane, yielding the final ligands 6a/6b without formation of side products.

Figure 2.

Synthesis scheme for 6a and 6b. (i) Benzylbromide (0.7 equiv), K2CO3, MeCN, rt, 16h. (ii) tert-butylpromoacetate (2 equiv), K2CO3, MeCN, rt, on (iii) Pd/C, MeOH, rt, 3h (iv) NHS-Ibuprofen, DIPEA (2 equiv), DMF, rt, 48h (v) TFA/DCM (2:1), rt, 16h.

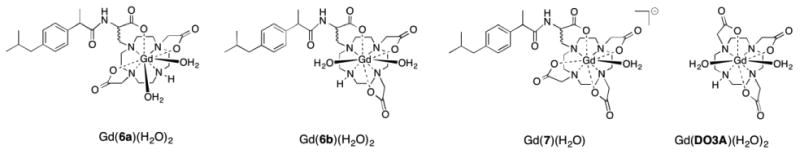

Complexes Gd(6a)(H2O)2 and Gd(6b)(H2O)2 (Figure 3) were formed under standard conditions by mixing the ligand with an aqueous solution of the lanthanide trichloride salt. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 7 by dropwise addition of a 0.1 M solution of NaOH. Complexation was followed by analytical HPLC in order to confirm that >95% of ligand was complexed. A slight excess of ligand was used to insure that there was no excess, unchelated Ln3+ present which would impact the veracity of the relaxivity and luminescence results. We also used the Xylenol Orange test to further confirm that there was no free lanthanide present.39 The lanthanide complexes each comprise a group of diastereoisomers because of the two chiral carbon centers in the molecule, because of chirality induced by the metal ion, and likely the presence of twisted square antiprism (TSAP) and square antiprism geometries. No effort was made to resolve these isomers.

Figure 3.

Gd complexes Complexes [Gd(6a)(H2O)2], [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] and [Gd(7)(H2O)]-. [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2] is shown as a reference.

Water exchange kinetics

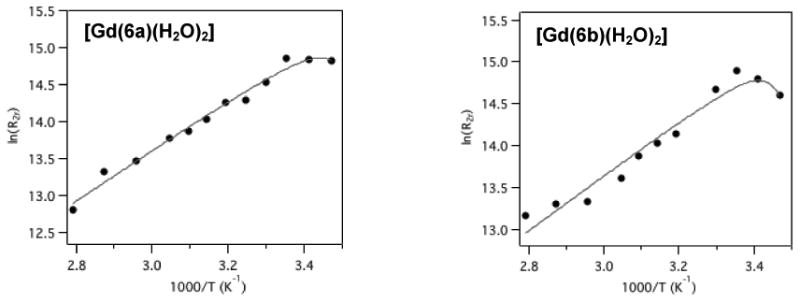

The removal of a carboxylate donor to increase the hydration number of a Gd(III) complex can lead to a decrease21 or an increase40 of the inner-sphere water exchange rate when compared to the parent q=1 complex. We measured water exchange kinetics for the Gd(III) complexes by variable temperature measurement of the transverse relaxation time of H217O in the presence and absence of each Gd(III) complex at 11.7 T. We calculated the transverse O-17 relaxivity, r2O, and found that the maximum r2O value was consistent with two coordinated water ligands. The maximum r2O values were 50, 52, and 49 mM-1s-1 for [Gd(6a)(H2O)2], [Gd(6b)(H2O)2], [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2], respectively. This is consistent with the luminescence lifetime data for the Tb(III) complexes, vide infra. Figure 4 shows the natural logarithm of the reduced transverse relaxation rate R2r as a function of reciprocal temperature. We used a 4-parameter model described previously36 to fit the data and found indistinguishable water exchange kinetics for both [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2], Table 1. These water exchange rates are similar, but slower than the related q=1 complexes [Gd(DOTAla)(H2O)]- and [Gd(DOTAlaP)(H2O)]2-. One possible explanation for the reduced exchange rate is decreased crowding around the sites for water coordination when compared with the q=1 complexes. Another explanation is the increased positive charge which often results in slower water exchange kinetics. The water exchange rate for [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] is about twice as fast as for [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2] which may be due to the greater spatial demand of the functionalized amino-propionate arm when compared with a simple, non-functionalized acetate arm.

Figure 4.

Temperature dependence of the 17O NMR (11.7 T) reduced transverse relaxation rates of [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] in PBS, in presence of 5% H217O. Solid line represents fit to the data.

Table 1. Summary of experimentally obtained water exchange rates, activation enthalpies, and mean water residency time at 310K for of [Gd(6a)(H2O)2], [Gd(6b)(H2O)2], and Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2 from reference 30).

Relaxivity in the presence of coordinating anions

One of the major limitations of q=2 Gd(III) complexes is their propensity to form ternary complexes with biologically relevant coordinating anions. Parker and coworkers have studied this phenomenon in detail using various DO3A type derivatives and found that sterically restrictive systems are indeed capable of shielding the water coordination sites from access of the coordinating anion.30, 41, 42 We were interested in testing if the sterically more demanding propionate of 6a and 6b would have such an effect when coordinated to Gd, compared to [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2] which is known to form ternary complexes with coordinating anions.42 We determined relaxivities in the presence of the following buffers at pH 7.4: HEPES (non-coordinating, 50 mM), phosphate (coordinating, 25 mM), lactate (coordinating, 20 mM), bicarbonate (coordinating, 20 mM). Results are summarized in Table 2. We used complex concentrations of 0.2 mM and lower to insure that the coordinating anion was present at ≥100-fold excess. The relaxivity measured in the presence of HEPES was representative of a typical q=2 complex with a molecular weight of 719 Da.3 In presence of 20 mM lactate or 20 mM bicarbonate, however, the relaxivity is strongly decreased. Interestingly, the relaxivity of the 1,4 isomer [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] is 15% higher than the 1,7 isomer and this increase is maintained when measured under the different buffer conditions. We also estimated the inner-sphere relaxivity measured in the presence of coordinating anions to relaxivity measured in HEPES buffer. For this, used the relaxivity of a Gd(TTHA) derivative reported previously that is known to be q=0. That compound exhibited a relaxivity of 1.70 mM-1s-1 at 60 MHz, 37 °C, and we assume here that the outer/second-sphere contribution to these complexes is also 1.70 mM-1s-1. This seems a good approximation as the relaxivities of [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2] in bicarbonate or lactate approach this limiting value and suggest a q=0 complex, consistent with the literature. The low relaxivity of Gd(6a) and Gd(6b) measured in lactate and bicarbonate no longer corresponds to what one would expect for a q=2 Gd complex, but still has considerable contribution from inner-sphere water. In the presence of 25 mM phosphate however, we found that relaxivity increased in contrast to what we observed for [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2]. In the case of [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2], relaxivity was reduced by almost 20% when compared to relaxivity measured in HEPES, however for [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2], the relaxivity is 18% higher.

Table 2. Relaxivities measured in the presence of different buffers at 37 °C and 60 MHz with ≥100-fold excess buffer concentration relative to [Gd].

| Complex | HEPES (50 mM) [mM-1s-1] |

Phosphate (25 mM) [mM-1s-1] |

Lactate (20mM) [mM-1s-1] |

Bicarbonate (20mM) [mM-1s-1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd(DO3A) | 4.4 | 3.7 | 1.89 | 1.7 |

| Gd(6a) | 7.02 | 8.25 | 3.7 | 3.12 |

| Gd(6b) | 8.06 | 9.5 | 4.5 | 3.73 |

|

| ||||

| Estimated inner-sphere relaxivity contribution [mM-1s-1] (estimated residual q) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Gd(DO3A) | 2.7 (2) | 2 (1.48) | 0.19 (0.07) | 0 (0) |

| Gd(6a) | 5.32 (2) | 6.55 (2.46) | 2 (0.75) | 1.42 (0.53) |

| Gd(6b) | 6.36 (2) | 7.8 (2.45) | 2.8 (0.88) | 2.03 (0.64) |

Tb luminescence

We also prepared the Tb complex [Tb(6a)(H2O)2]. Conveniently, the aromatic residue of ibuprofen acts as an antenna for Tb luminescence, which leads to a great increase in luminescence intensity. This in turn allows for measurements of luminescence lifetime using [Tb(6a)(H2O)2] solutions at concentrations of 0.4 - 1 mM with our fluorimeter. Luminescence lifetime measurements of [Tb(6a)(H2O)2] gave q values that reflected the relaxivity measurements. In the HEPES buffer and in the presence of phosphate, q = 2, while there was a marked decrease to q = 0.5 in the presence of bicarbonate, and q = 0.25 in the presence of lactate, Table 3.

Table 3. Luminescence lifetime constants of [Tb(6a)(H2O)2] measured in presence of different anions.

| Anion | 1/τ(H2O) | 1/τ(D2O) | q (calcd.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| -- | 0.91 | 0.47 | 1.9 |

| Phosphate | 0.89 | 0.47 | 1.8 |

| Bicarbonate | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.5 |

| Lactate | 0.7 | 0.59 | 0.25 |

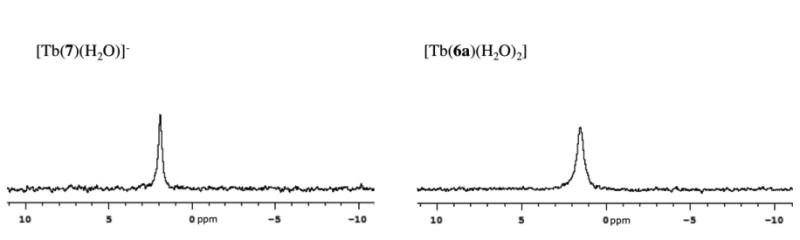

Luminescence lifetime showed no change in q in the presence of phosphate indicating that phosphate does not form an inner-sphere complex with [Tb(6a)(H2O]. However the relaxivity of [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] increased in the presence of phosphate, suggesting the presence of a second-sphere complex with phosphate. This was tested by measuring the 31P NMR spectrum of phosphate in presence of either [Tb(6a)(H2O)2] or [Tb(7)(H2O)]-. The latter compound showed no change in relaxivity in the presence of phosphate. We observed a considerable increase of the linewidth of the phosphate resonance in the presence of [Tb(6a)(H2O)2] (76.1 Hz), when compared with the phosphate resonance in presence of an equivalent concentration of [Tb(7)(H2O)]- (34.1 Hz) as illustrated in Figure 5. This result supports the presence of a second-sphere complex between [Tb(6a)(H2O] and phosphate. This organization of the second-sphere may result in the presence of second-sphere water ligands with longer residency times promoting higher relaxivity. Alternately, the hydrogen phosphate itself may undergo relaxation and protic exchange leading to higher relaxivity.

Figure 5.

31P-NMR spectra of phosphate buffer in presence of [Tb(7)(H2O)]- (left) and [Tb(6a)(H2O)2] (right), at 202.404 MHz.

Proton relaxivity of [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] in the presence of human serum albumin (HSA)

We designed [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] to be analogous to [Gd(7)(H2O)]-,33 which is capable of binding albumin through the ibuprofen residue. In the case of [Gd(7)(H2O)]-, we observed an almost 5 fold relaxivity gain at 60 MHz in the presence of HSA (4.8 to 22.4 mM-1s-1, 37 °C).33 The relaxivities of [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] are increased in the presence of HSA (13.5 and 12.7 mM-1s-1 at 37 °C and 60 MHz), but these relaxivities are considerably lower than that observed for q = 1 [Gd(7)(H2O)]-. The lower than expected relaxivities are not a result of poor albumin binding. Both complexes appeared to bind to HSA efficiently (82% (Gd(6a)) and 75% (Gd(6b)) bound, 4.5% w/v HSA, 0.1 mM Gd(III), 37 °C, compared to 70% bound for Gd(7) under the same conditions). This relatively low relaxivity is likely due to displacement of the water ligands by a coordinating amino acid side chain from the protein. Similar displacement of coordinated water ligands in Gd(DO3A)-type systems has been observed previously.22 Evidently the increased size of the propionate arm compared to the acetate arm again is not able to fully prevent binding of protein side chains in the case of [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] either, resulting in a complex with a strongly decreased q. We attempted to measure the hydration number of [Tb(6a)(H2O)n] in the presence of HSA, but we were hampered by the power of our fluorimeter. Direct excitation of Tb3+ required too high a concentration to have the HSA present in excess; on the other hand when we used sensitized emission via the ibuprofen handle, there was too much absorption of light by the protein. Despite these limitations we were able to acquire good luminescence decay data under the conditions 0.015 mM HSA, 0.7 mM [Tb(6a)(H2O)n] and found that q had decreased to 0.75 from 1.9 (value measured in absence of HSA). This value reflects a mixture of HSA-bound and unbound complex and the q value of the HSA-bound complex is undoubtedly lower.

We also compared the relaxivity values obtained known q=0 complexes bound to HSA under the same conditions. In 4.5 % w/v HSA, 60 MHz 37 °C, the relaxivity of the q=0 DOTA-picolinate derivative reported by Dumas et al.3 was 5.96 mM-1s-1, while the q=0 TTHA analog of MS-32521 gave a relaxivity of 6.53 mM-1s-1. The fact that the relaxivities of [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] are higher suggests that while they certainly have decreased inner-sphere hydration, the inner-sphere water molecules are not entirely displaced.

Kinetic inertness under forcing conditions

By decreasing the number of donor atoms of the ligands 6a and 6b by omission of one of the acetate arms compared to 7, it is evident that kinetic inertness of the corresponding lanthanide complex will also decrease. This is a behavior that has been well documented in literature by us4 and others.43, 44 We previously evaluated the kinetic inertness of various other Gd(DOTAla)-type derivatives by challenging the corresponding Gd complex 1 equivalent MS-325 ligand at pH 3 (MS-325 ligand is a DTPA derivative45). The transchelation is monitored via HPLC. Previously, we were able to establish a half-life of 115 h for [Gd(7)(H2O)]- under these conditions.34 We tested [Gd(6a)(H2O)2], [Gd(6b)(H2O)2], and [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2] under the same conditions. We found that these three q = 2 complexes display similar lability and are about 100 times more labile than [Gd(7)(H2O)]- with respect to transchelation, Table 5. This behavior is as expected. When comparing [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] with [Gd(6b)(H2O)2], there is a two-fold difference in the measured half-life, with the 1,7 isomer being slightly more inert. With a kinetic inertness comparable to [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2], the new DO3Ala derivatives [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] and [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] may be at the border of what is acceptable for in vivo use.

Table 5. Half-life (t1/2) for transchelation of Gd by the MS-325 ligand at pH 3, 37 °C for the complexes discussed here. Data for [Gd(7)(H2O)]- from reference.34.

| Complex | t1/2 (h) |

|---|---|

| [Gd(6a)(H2O)2] | 1.21 |

| [Gd(6b)(H2O)2] | 0.45 |

| [Gd(DO3A)(H2O)2] | 1.5 |

| [Gd(7)(H2O)]- | 115 |

Conclusions

In summary, we have successfully synthesized two isomers of DO3Ala, the heptadentate version of the single amino acid chelator DOTAla. Overall, the Gd(III) complexes with these two isomers behaved remarkably similar in terms of kinetic inertness with respect to transmetallation, relaxivity, anion binding, and water exchange kinetics. As the kinetic inertness for both derivatives is strongly decreased and because of the propensity of these complexes to coordinate anions, these complexes are likely not suitable candidates for further development as gadolinium-based imaging agents. DO3Ala may however provide a suitable, easily functionalizable platform for synthesis of kinetically inert complexes with smaller metal ions.

Supplementary Material

Table 4. Relaxivities measured in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) or in presence of 4.5% HSA at 37 °C, at 20 and 60 MHz.

| 20 MHz, 37 °C [mM-1s-1] | 60 MHz, 37 °C [mM-1s-1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | PBS | 4.5% HSA | PBS | 4.5% HSA |

| 6a | 7.4 | 15.2 | 8.25 | 13.5 |

| 6b | 8.3 | 15.1 | 9.5 | 12.7 |

| 7 | 5.6 | 37.2 | 4.8 | 22.4 |

Synopsis.

Two structural isomers of the heptadentate chelator DO3Ala were synthesized, with carboxymethyl groups at either the 1,4- or 1,7-positions of the cyclen macrocycle. The corresponding Gd complexes were interrogated for their kinetic inertness, mean water residency time and relaxivity in presence of various coordinating anions as well as human serum albumin.

Acknowledgments

P. C. acknowledges the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering for funding for this project (NIBIB, award R01EB009062), and the National Center for Research Resources for instrumentation grants (S10OD010650, S10RR023385, P41RR14075). E.B. thanks the Swiss National Science Foundation (advanced.postdoc mobility fellowship) for support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting Information. LC-MS traces of the Gd(III) and Tb(III) complexes. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Caravan P. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:512–523. doi: 10.1039/b510982p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan KWY, Wong WT. Coord Chem Rev. 2007;251:2428–2451. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dumas S, Jacques V, Sun WC, Troughton JS, Welch JT, Chasse JM, Schmitt-Willich H, Caravan P. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:600–612. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ee5a9e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polasek M, Caravan P. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:4084–4096. doi: 10.1021/ic400227k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudovský J, Cígler P, Kotek J, Hermann P, Vojtíšek P, Lukeš I, Peters JA, Vander Elst L, Muller RN. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:2373–2384. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudovský J, Kotek J, Hermann P, Lukes I, Mainero V, Aime S. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:112–117. doi: 10.1039/b410103k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mastarone DJ, Harrison VSR, Eckermann AL, Parigi G, Meade TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5329–5337. doi: 10.1021/ja1099616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song Y, Kohlmeir EK, Meade TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6662–6663. doi: 10.1021/ja0777990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali MM, Woods M, Caravan P, Opina AC, Spiller M, Fettinger JC, Sherry AD. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:7250–7258. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tóth É, Vauthey S, Pubanz D, Merbach AE. Inorg Chem. 1996;35:3375–3379. doi: 10.1021/ic951492x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nivorozhkin AL, Kolodziej AF, Caravan P, Greenfield MT, Lauffer RB, McMurry TJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2903–2906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen JW, Querol Sans M, Bogdanov Jr A, Weissleder R. Radiology. 2006;240:473–481. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livramento JB, Sour A, Borel A, Merbach AE, Tóth É. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:989–1003. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livramento JB, Helm L, Sour A, O'Neil C, Merbach AE, Tóth É. Dalton Trans. 2008:1195–1202. doi: 10.1039/b717390c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Z, Greenfield MT, Spiller M, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB, Caravan P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:6766–6769. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Z, Kolodziej AF, Greenfield MT, Caravan P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:2621–2624. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kielar F, Tei L, Terreno E, Botta M. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7836–7837. doi: 10.1021/ja101518v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacques V, Dumas S, Sun WC, Troughton JS, Greenfield MT, Caravan P. Inves Radiol. 2010;45:613–624. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ee6a49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar K, Chang CA, Tweedle M. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:587–593. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruce JI, Dickins RS, Govenlock LJ, Gunnlaugsson T, Lopinski S, Lowe MP, Parker D, Peacock RD, Perry JJB, Aime S, Botta M. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9674–9684. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caravan P, Amedio JC, Dunham SU, Greenfield MT, Cloutier NJ, McDermid SA, Spiller M, Zech SG, Looby RJ, Raitsimring AM. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:5866–5874. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raitsimring AM, Astashkin AV, Baute D, Goldfarb D, Poluektov OG, Lowe MP, Zech SG, Caravan P. Chem Phys Chem. 2006;7:1590–1597. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200600138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moriggi L, Yaseen MA, Helm L, Caravan P. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:3675–3686. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gale EM, Kenton N, Caravan P. Chem Commun. 2013;49:8060–8062. doi: 10.1039/c3cc44116d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aime S, Calabi L, Cavallotti C, Gianolio E, Giovenzana GB, Losi P, Maiocchi A, Palmisano G, Sisti M. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:7588–7590. doi: 10.1021/ic0489692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baranyai Z, Uggeri F, Maiocchi A, Giovenzana GB, Cavallotti C, Takács A, Tóth I, Bányai I, Bényei A, Brucher E, Aime S. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2013;2013:147–162. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bretonnière Y, Mazzanti M, Pécaut J, Dunand FA, Merbach AE. Chem Commun. 2001:621–622. doi: 10.1021/ic010591+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Datta A, Raymond KN. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:938–947. doi: 10.1021/ar800250h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pellegatti L, Zhang J, Drahos B, Villette S, Suzenet F, Guillaumet G, Petoud S, Toth E. Chem Commun. 2008:6591–6593. doi: 10.1039/b817343e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Messeri D, Lowe MP, Parker D, Botta M. Chem Commun. 2001:2742–2743. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baranyai Z, Botta M, Fekete M, Giovenzana GB, Negri R, Tei L, Platas-Iglesias C. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:7680–7685. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boros E, Polasek M, Zhang Z, Caravan P. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:19858–19868. doi: 10.1021/ja309187m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boros E, Caravan P. J Med Chem. 2013;56:1782–1786. doi: 10.1021/jm4000177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boros E, Karimi S, Kenton N, Helm L, Caravan P. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:6985–6994. doi: 10.1021/ic5008928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pouyani T, Prestwich GD. Bioconjugate Chem. 1994;5:339–347. doi: 10.1021/bc00028a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caravan P, Parigi G, Chasse JM, Cloutier NJ, Ellison JJ, Lauffer RB, Luchinat C, McDermid SA, Spiller M, McMurry TJ. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:6632–6639. doi: 10.1021/ic700686k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powell DH, Dhubhghaill OMN, Pubanz D, Helm L, Lebedev YS, Schlaepfer W, Merbach AE. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:9333–9346. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMurry TJ, Parmelee DJ, Sajiki HS, D M, Ouellet HS, Walovitch RC, Tyeklar Z, Dumas S, Bernard P, Nadler S, Midelfort K, Greenfield M, Troughton J, Lauffer RB. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3465–3474. doi: 10.1021/jm0102351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barge A, Cravotto G, Gianolio E, Fedeli F. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2006;1:184–188. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toth E, Dhubhghaill OMN, Besson G, Helm L, Merbach AE. Magnet Reson Chem. 1999;37:701–708. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowe MP, Parker D, Reany O, Aime S, Botta M, Castellano G, Gianolio E, Pagliarin R. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7601–7609. doi: 10.1021/ja0103647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dickins RS, Aime S, Batsanov AS, Beeby A, Botta M, Bruce JI, Howard JAK, Love CS, Parker D, Peacock RD. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12697–12705. doi: 10.1021/ja020836x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tweedle MF, Hagan JJ, Kumar K, Mantha S, Chang CA. Magn Reson Im. 1991;9:409–415. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(91)90429-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar K, Tweedle MF. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:4193–4199. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lauffer RB, Parmelee DJ, Dunham SU, Ouellet HS, Dolan RP, Witte S, McMurry TJ, Walovitch RC. Radiology. 1998;207:529–538. doi: 10.1148/radiology.207.2.9577506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.