Abstract

Adverse pregnancy conditions in women are common and have been associated with adverse cardiovascular and metabolic outcomes such as myocardial infarction and stroke. As risk stratification in women is often suboptimal, recognition of non-traditional risk factors such as hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and premature delivery has become increasingly important. Additionally, such conditions may also increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in the children of afflicted women. In this review, we aim to highlight these conditions, along with infertility, and the association between such conditions and various cardiovascular outcomes and related maternal risk along with potential translation of risk to offspring. We will also discuss proposed mechanisms driving these associations as well as potential opportunities for screening and risk modification.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Preterm birth, Hypertension, Stroke, Myocardial infarction

Introduction

Despite advancements in management, cardiovascular (CV) disease remains the most prevalent cause of morbidity and mortality. This is particularly true in women who often present late with atypical symptoms and are often misdiagnosed and undertreated. Women are much more likely to have non-obstructive coronary artery disease yet their mortality and other adverse outcomes remain significantly elevated compared with men [1]. This has been attributed in part to the increased frequency of coronary microvascular dysfunction and other coronary and non-coronary-related disorders that contribute to ischemia and related adverse outcomes in these patients [2, 3]. Along these same lines, as diagnosis remains challenging in this population, so does risk stratification. Risk stratification has traditionally been inaccurate in this population as traditional risk scores tend to categorize most women as low risk. This has led to a move toward more sex-specific risk stratification with inclusion of alternative markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) in the Reynolds risk score [4] or inclusion of stroke in the ACC/AHA Atherosclerotic CV Disease (ASCVD) risk score [5]. Another area that has remained significantly under-appreciated is the impact of adverse pregnancy outcomes. These conditions often occur in young otherwise healthy appearing women who under the “stress test” of pregnancy demonstrate future tendencies toward metabolic and CV conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. Additionally, these and other conditions such as infertility may be linked to future CV risk in not only the mother but in the offspring as well. In this manuscript, we aim to review these conditions highlighting their associations with future adverse CV conditions in both mother and child.

Background

Pregnancy is a period of pronounced physiologic change required to meet the metabolic demands necessary to promote fetal growth. There is a significant increase in cardiac output, particularly early in the first trimester, which can rise 30 to 50 % above baseline during normal pregnancy; half of this increase typically occurs by 8 weeks gestation [6–10]. Along with increase in blood volume, there is fluctuation in blood pressure due to decrease in peripheral vascular resistance in the second trimester with an increase back toward pre-pregnancy levels during the third trimester. In addition to hemodynamic changes, metabolic and immune responses occur. Inflammatory markers such as CRP have been found elevated in pregnant, compared with non-pregnant, women, and this is believed to potentially reflect an increase in oxidative stress during pregnancy [11]. However, CRP levels may also indicate abnormal inflammation leading to spontaneous preterm birth [12]. Hormones within the placenta also alter lipid and glucose metabolism to counter the demands of a growing fetus with increases in multiple components of total cholesterol [13–15]. Additionally, up-regulation of pancreatic function occurs early within pregnancy to maintain maternal glucose homeostasis, with subsequent return to pre-pregnancy level. However, dysregulation of these processes may manifest during pregnancy and signal increased CV risk for later in life [16, 17]. Adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm delivery and low birth weight may also manifest as a risk factor for CV disease later in maternal life.

Adverse Pregnancy Conditions

Definition and Prevalence of Adverse Pregnancy Conditions

Adverse pregnancy conditions include both maternal adverse outcomes (during pregnancy and up to 6 weeks postpartum) and neonatal adverse outcomes (Table 1) [18]. Maternal adverse outcomes that have been associated with future CV health include gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (gestational hypertension and preeclampsia). Neonatal adverse outcomes include low birth weight (<2500 g or below 10th percentile for gestational age) and preterm birth (before 37 weeks). Approximately 30 % of parous women have had one of these adverse pregnancy conditions, and it is estimated that 6 % of women have had more than one adverse pregnancy condition [19, 20]. Each of these adverse pregnancy conditions is associated with a 2-fold increased risk in future CV disease and linked with traditional CV risk factors [19]; thus with the high prevalence of adverse pregnancy conditions, a substantial population of women may be identified for early CV risk stratification. In addition, 11 % of women age 15–44 in the United States experience challenges with infertility [21]; while female infertility is not considered an adverse pregnancy outcome, women with infertility may be at increased risk of having an adverse pregnancy outcome [22, 23].

Table 1.

Adverse Pregnancy Conditions and Associated Future Cardiovascular Disease Risk

| Adverse Outcomes | Associated Future Risk Condition |

|---|---|

| Maternal | |

| Gestational diabetes | Type-2 diabetes, accelerated atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (gestational hypertension, preeclampsia) | Chronic hypertension, ischemic heart disease, stroke |

| Neonatal | |

| Low birth weight | Ischemic heart disease, increased cardiovascular mortality |

| Preterm birth | Chronic hypertension, increased cardiovascular events |

Gestational Diabetes

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) occurs in 5–10 % of pregnancies and is defined as glucose intolerance that begins or is first identified during pregnancy [24, 25]. GDM is associated with increased CV risk (adjusted odds ratio of 1.85 in women with family history of diabetes) independent of the development of future type-2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, and CV events occur approximately 7 years earlier compared with women without GDM [26]. GDM is associated with higher fasting glucose and insulin levels measured 18 years after pregnancy [19] and a higher risk of developing type-2 diabetes (7.4-fold increased risk compared with those with normoglycemia during pregnancy) [27]. Since type-2 diabetes is itself an independent predictor of CV events, women with GDM should receive continued medical follow-up and early lifestyle or medical interventions aimed at reducing risk of development into diabetes. While CV deaths in diabetic women have declined since 1997, mortality risk remains high at about 2 CV deaths per 1000 person-years [28].

Accelerated atherosclerosis is present in women with GDM, as documented recently in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study [29]. Here an increase in carotid intimal medial thickness (CIMT), a subclinical measure of early atherosclerosis, occurred in women with history of GDM before the onset of type-2 diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome. Elevated CIMT in GDM was also independent of maternal age, ethnicity, and pre-pregnancy obesity. This challenges the prior conception that the higher CV disease risk related to GDM is primarily due to the increased risk of future type-2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Women who develop GDM have insufficient pancreatic β-cell secretion of insulin to meet the demands of pregnancy, and mechanistic pathways have included autoimmune β-cell dysfunction, genetic abnormalities that lead to impaired insulin secretion, and β-cell dysfunction related to chronic insulin resistance [25]. Elevated markers of endothelial dysfunction (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, e-selectin) in women with GDM are associated with subclinical inflammation and thrombosis and insulin sensitivity [30], and further research is needed to determine whether vascular measures of endothelial function can help identify women with GDM at highest risk for future CV events.

The American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) has adopted universal screening for GDM, given that the majority of women in the United States have risk factors for GDM (e.g., obesity or 1st degree family member with history of diabetes). The ACOG recommends a two-step approach for screening, which includes an abnormal 1-hour screen glucose of 135–140 mg/dL and two abnormal values on the 3-hour oral glucose tolerance test that includes a fasting value [31]. Women with GDM are then recommended to undergo preventive CV counseling, early postpartum screening for diabetes, and annual repeat screening for diabetes.

Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy include gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg in a previously normotensive pregnant woman who is ≥20 weeks of gestation and has no proteinuria or signs of new organ dysfunction, gestational hypertension occurs in 3–14 % of pregnancies [19, 32]. Preeclampsia is defined as presence of hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) at ≥20 weeks of gestation and the presence of one of the following signs of new end-organ dysfunction: proteinuria (≥300 mg in a 24-hour urine collection or 1+ on urine dipstick reading), thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000), renal insufficiency (creatinine >1.1 mg/dL), impaired liver function (transaminases elevated twice normal), pulmonary edema, or cerebral/visual symptoms [33]. Preeclampsia occurs in 3–5 % of all pregnancies and 25 % of preterm births [34].

In 2011, the American Heart Association added gestational hypertension and preeclampsia to its algorithm for evaluation of CV risk in women [35]. Gestational hypertension is associated with a 5-fold increase in development of chronic hypertension; women with both gestational hypertension and incident chronic hypertension have an almost 20 % risk of future CVevent compared with 3.6 % in women with gestational hypertension and no incident chronic hypertension [36]. Women with a history of preeclampsia have a 4-fold increased risk of developing chronic hypertension, 3-fold increased risk of developing type-2 diabetes, and a 2-fold increased risk for ischemic heart disease and stroke [37–39]. Preeclampsia’s independent association with CV death is not limited to the early postpartum period but is present throughout the woman’s lifetime (adjusted hazard ratio 2.14), as demonstrated by 30-year follow-up of 14,403 women in the Kaiser Permanente Child Health and Development Studies pregnancy cohort [40]. This study also demonstrated that CV risk is higher in women with early preeclampsia (onset ≤34 weeks gestation) compared with women diagnosed with preeclampsia later in pregnancy (onset >34 weeks gestation), regardless of pre-eclampsia severity. Studies have suggested that early vs late preeclampsia may have differing impact on dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and hemodynamics during pregnancy and postpartum, leading to differences in future CV risk [40].

Some of the increased CV risk associated with gestational hypertension and preeclampsia may be attributed to risk factors that were present before pregnancy, such as pre-pregnancy dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, body mass index (BMI), and blood pressure [41]. However, vascular damage occurring during gestational hypertension or preeclampsia is also considered a contributing factor to the development of future CV events. In fact, endothelial dysfunction is observed at 23 weeks gestation in women who develop preeclampsia later in the pregnancy, during preeclampsia itself, and even at least 3 months after preeclampsia has resolved [42]. The presence of endothelial dysfunction in these women is not explained by traditional maternal risk factors and is thought to be mediated by defects in placentation leading to placental ischemia and oxidative stress [42, 43]. Metabolic derangements such as hypertriglyceridemia and glucose intolerance may further contribute to CV dysfunction and increases the risk for recurrent preeclampsia [44].

The ACOG Task Force recommends that women with history of preeclampsia and preterm birth or recurrent preeclampsia should have annual assessment of their lipid profile, blood pressure, BMI, and fasting blood glucose [33]. These women should also receive preventive CV counseling including diet, exercise, and smoking cessation.

Low Birth Weight and Preterm Birth

Preterm birth, defined as birth occurring prior to 37 weeks gestation, is a relatively common occurrence affecting approximately 10 % of births in the US [45]. Recent studies support an increasing link between preterm birth and increase in maternal risk for CV disease [46–50]. Among a cohort of nearly 50,000 women who delivered between 1988 and 1999 and were followed until 2010, those with preterm delivery had a significantly high risk of future CV hospitalizations [51]. In another report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, it was reported that although other metabolic risk factors such as glycemic control and lipids were similar, women who had a history of preterm birth had a higher incidence of hypertension [19]. A similar association was noted in another study independent of hypertension during pregnancy, although the association was more robust in planned preterm birth, which is generally indicated due to medical necessity, indicating a potential common link for preterm birth and CV risk [52]. The later risk of CV disease may also be proportional with recurrent preterm delivery with higher risk being noted in multiparous women [53, 54].

Of the infants who are classified as low birth weight (defined as <2500 grams) in the United States, two thirds are born preterm, representing significant overlap between these two conditions. Low birth weight occurs in approximately 8 % of live births in the United States [55]. In addition to preterm infants, other low-birth-weight infants are considered to be small-for-gestational-age (SGA, most commonly defined as a fetal weight or birth weight below the 10th percentile at a particular gestational week) [56]. In an analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, there was an association between giving birth to an SGA infant and maternal risk of ischemic heart disease [57]. In meta-analysis data by Davey-Smith, there was an inverse correlation between delivery weight and maternal CV mortality, that is, higher birth weight equated with lower risk [47, 50]. However, extension of this association must be tempered to an extent by the known association of large infant size (macrosomia) and risk of maternal diabetes. Of interest, the risk associated with low birth weight may also be modified by race, as noted in a 2014 NHANES study which found that the risk associated between low birth weight and maternal hypertension may be higher in black women [58].

It is important to note that studies have suggested that between spontaneous versus medically indicated preterm birth, there is a stronger association of CV risk with planned preterm birth. However, this is likely attributable to co-existing conditions that led to planned preterm birth, such as pre-eclampsia or premature rupture of membranes, with medical necessity driving early delivery. In a study that assessed indications for preterm delivery, planned delivery was associated with higher risks of CV mortality than was spontaneous preterm delivery [59]. Additionally, hypertensive preterm deliveries consistently have a stronger association with maternal CV adverse outcomes than do normotensive preterm deliveries, although the latter are still associated with a 1- to 3-fold increased risk compared with term deliveries [53, 60].

Risk Mechanisms

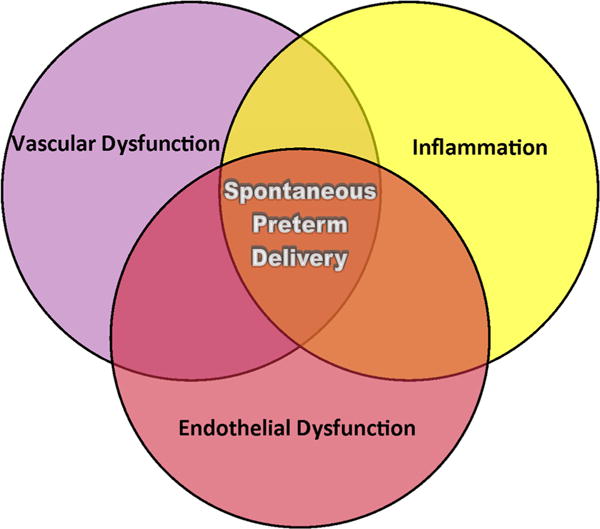

The physiologic mechanisms driving the associations between adverse pregnancy conditions and CV risk are not completely understood. There is evidence to support underlying vascular dysfunction as a common link between preterm birth/low birth weight and future CV risk [53, 61]. Inflammation may also play an important role, with women with history of preterm birth noted to have increased levels of C-reactive protein [12]. Although further research is needed to better understand these associations, it is likely a complex interaction between multiple vascular and inflammatory pathways (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Possible Mechanistic Pathways of Spontaneous Preterm Delivery and Maternal CVD Risk. Women with spontaneous preterm delivery have an increased risk of future CVD events and are suspected to have greater vascular dysfunction, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction

Parity and Infertility

Infertility and parity have been associated with an increase in maternal CV risk. There has been some thought that parity in itself is associated with CV risk, although the exact associations are not clear. Parity evaluated in cross-sectional analyses has been associated with increased risk of CV disease in women in many, but not all, studies. In one study, women with at least one pregnancy, even without complication, were twice as likely to have CVD compared with women who had never been pregnant. In this same study, those women who had a complication during pregnancy experienced a near tripling of CV disease risk [62]. Some studies indicate that each live birth confers additional, albeit modest, risk for prevalent maternal CV disease or atherosclerosis [63, 64]. Alternatively, other studies have found a threshold effect such that women with more than five or six children have excess CV disease risk [65, 66]. Also parity has been associated with maternal CV disease risk in a J-shaped fashion, even after accounting for socioeconomic factors and pregnancy-related complications [67].

Infertility affects approximately 11 % of reproductive-age women in the United States [21]. It has been suggested that the inability to conceive in itself is associated with adverse CV outcomes, although this is difficult to distinguish as many patients have metabolic conditions, which could potentially affect both fertility and CV risk. In women who have some level of infertility but eventually still conceive, there is evidence for increase in risk even when accounting for traditional CV risk factors [68]. In addition to adverse pregnancy outcomes and CV risk, there is some evidence supporting an association with recurrent miscarriage as well. In a large cohort of nearly 12,000 women in Germany, those women with three or more miscarriages or at least one still-born child had significantly increased risk of future myocardial infarction [69].

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

In addition to miscarriage, several conditions that are associated with infertility have also been implied to carry excess CV risk, including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and premature ovarian failure. PCOS is the most common endocrine disorder of women of reproductive age, affecting from 6 to 8 % of women overall [70]. Primary characteristics include irregular or absent menses, anovulation, and hyperandrogenism [71]. Testosterone is the main circulating active androgen, and the total serum testosterone concentration is the first-line recommendation for assessing androgen excess in women [72].

The association is well known between PCOS and CV risk factors such as the metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome occurs in approximately 30–40 % of patients with PCOS [73–75]. In patients with this condition, there is some degree of insulin resistance, and this is independent of obesity in women [76, 77] and ranges from impaired glucose tolerance to overt type-2 diabetes with increased risk in women with a family history of diabetes [78–82]. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is also very common in women with PCOS even when adjusting for BMI, and severity of OSA has been correlated with degree of glucose tolerance [83–85]. Women with PCOS also exhibit adverse lipid profiles, with elevated low-density lipoprotein levels in both obese and non-obese PCOS patients compared with controls [86, 87]. Additionally, in a retrospective analysis, women with PCOS were found to have higher serum concentrations of CRP, a marker of inflammation associated with CV risk, than BMI-matched control women without PCOS [88]. Women with PCOS also demonstrate evidence of impaired endothelial function as measured by flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery noted in the recent meta-analysis [89]. These women also tend to have more extensive coronary disease by angiography and computed tomography and increase in intima-media thickness on carotid imaging [90–92].

Whether the increase in CV risk factors associated with PCOS or whether the condition itself predisposes to CV events is unclear, and the data on long-term CV morbidity and mortality in women with PCOS are suggestive but not conclusive [82]. A study with nearly 500,000 person-years of follow-up demonstrated an association between menstrual irregularity and increased age-adjusted risk for CV mortality, although this association lost significance after adjusting for BMI [93]. However, a recent meta-analysis reported a twofold relative risk for arterial disease irrespective of BMI with an additional study supporting a correlation with risk of stroke [94, 95]. In another analysis from the Nurses’ Health Study, a history of irregular menses was associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease [96]. Additionally, the severity of the PCOS phenotype may also correlate with CV risk [97]. However, in a 30-year follow up, women who had received wedge resection surgery for presumed diagnosis of PCOS did not have an increased risk for CV disease despite the presence of metabolic risk factors such as diabetes [95, 98]. Discrepancy in findings may be due in part to inexact diagnoses of PCOS made on historical data suggesting PCOS diagnosis from a history of menstrual irregularity.

There has been concern that fertility therapy may lead to adverse CV effects due to effects on endothelial function, metabolic effects, and ovarian hyper stimulation. There has been a substantial increase in fertility therapy over the last two decades, particularly among older women [99]. However, the recently published GRAVID study, which assessed over a million women with nearly 10-year follow up, suggested that women who delivered after using fertility therapy actually had a lower rate of CV events than controls. These women also had a lower risk for all-cause mortality, thrombotic events, and depression [99]. This study differed from prior studies that had suggested an association between fertility therapy and CV risk [100, 101]. However, the GRAVID study had the longest follow-up period, and it was suggested that the findings may be due to lifestyle interventions in women receiving these treatments. As the use of assisted fertility therapies will only continue to increase, this is an important area of study that warrants further investigation.

Screening and Risk Modification

While gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are now included in CV risk stratification guidelines for women [35], other adverse pregnancy conditions are not widely recognized. In addition, CV risk calculators such as the Framingham risk score, Reynolds risk score, and 2013 ASCVD calculator do not incorporate these adverse pregnancy conditions, leading to potential underestimation of lifetime CV risk in women [5, 102, 103]. A major reason for the lack of sufficient evidence to incorporate these adverse pregnancy conditions into risk calculators is the inconsistency of methods for screening and diagnosis of adverse pregnancy conditions in large registries. An initial study evaluating maternal recall of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy demonstrated the limited clinical utility of maternal recall due to low sensitivity and predictive values [104]. More research is needed to determine whether incorporation of pregnancy history data will improve CV risk scoring systems for women. In the meantime, women with a history of adverse pregnancy condition may undergo further CV risk stratification with annual screening of blood pressure, lipids, and fasting glucose. Women with preeclampsia or gestational hypertension should follow-up with the physician for a blood pressure check within 1 week of delivery, while women with gestational diabetes should have repeat glucose testing at 6 weeks post-partum [31].

Noninvasive measures of subclinical atherosclerosis (such as CIMT and coronary artery calcium scoring), of endothelial dysfunction (brachial artery testing, peripheral arterial tonometry), or of inflammation (CRP) may play a role in risk stratification of women with highest-risk adverse pregnancy conditions, such as those with early preeclampsia, but research trials are needed to demonstrate that these measures will improve CV outcomes.

Translation of CV Risk in Offspring

In addition to the potential increase in CV maternal risk related to adverse pregnancy conditions and infertility, there is increasing evidence that these same conditions may predispose to adverse CV events in offspring. Stemming from hypotheses proposed by Barker that in utero compromise predisposes the fetus to the development of CV disease, there is evidence that adult CV conditions may develop due to adverse conditions during fetal development [105]. Early “programming” may occur in utero and have significant effects on vascular development and response [106, 107]. There is evidence that manifestations of maternal conditions may be exhibited very early in the fetus. Examination of spontaneously aborted fetal aortas and extracranial arteries in autopsy studies have demonstrated significant fatty streak formation associated with maternal hypercholesterolemia [108, 109]. Thus, although the expression of CV risk factors and disease may occur later in adult life, the effects of adverse maternal conditions may present much earlier during fetal development. These may represent epigenetic effects on fetal vasculature and endothelial repair mechanisms leading to vascular dysregulation [110].

Preterm birth has emerged as a potential marker for future CV risk in offspring. Primarily over the last decade, data have emerged suggesting prematurity as a potential risk factor for hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and increase in overall CV mortality [111–113]. However, the association of preterm birth with specific CV disease associations has not been consistent. In a recent 2014 Swedish cohort study, birth before 32 weeks was associated with a doubling of cerebrovascular disease risk compared with infants born full term. However, preterm birth was not associated with later risk of ischemic heart disease [114]. A more differential association with stroke may be plausible due to the association between preterm birth and risk of hypertension which is known to be associated with risk of cerebrovascular disease. Disruption of the vascular development along with kidney development may explain a differential risk with stroke [115–119]. However, this association may be different for impaired fetal growth as, in another Swedish cohort, impaired fetal growth was associated with later increase in CV risk factors as well as ischemic heart disease [49, 120]. Additionally, these risk associations may vary by sex as preterm birth was associated with elevated blood pressure in adolescent girls compared with boys [121].

Offspring of hypertensive pregnancies have also been found to be at greater risk of higher blood pressure in childhood [122–126]. Data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children demonstrated higher blood pressure in children born to mothers with hypertensive pregnancies and preeclampsia compared with offspring born to non-hypertensive mothers. They found no difference in insulin or lipid levels [127]. Another systematic review found that offspring of women with pre-eclampsia had higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures in childhood versus those born to normotensive mothers [128]. Additionally, there is some evidence that there is a gradation of risk, in that those mothers who had more severe hypertension along the spectrum of pre-eclampsia had the offspring with the highest risk for hypertension [129]. Similar to low birth weight, pre-eclampsia has also been associated with increase stroke risk in offspring. In a study of over 6000 infants in Finland, there was noted to be a near doubling of stroke risk in those born to mothers who suffered from pre-eclampsia and 40 % increase in risk in those born to mothers with gestational hypertension. However, they did not find an association with later risk of coronary disease in offspring [129].

In addition to the potential translation of maternal adverse condition to the child, there may be some increase in risk in offspring of those whose mothers underwent assisted reproductive treatment, specifically with hypertension and pulmonary vascular dysfunction [130–132]. More specifically, ovarian hyper stimulation syndrome (OHSS) is a potentially dangerous condition characterized by elevated serum estradiol level, severe ovarian cysts, and intravascular fluid shifts [133] that may occur in women undergoing fertility therapy. In one analysis, children born to women experiencing OHSS were found to have alterations in cardiac diastolic function compared with non-OHSS in vitro fertilization children, and may have an increased risk of CV dysfunction [134].

Potential Mechanisms Driving Offspring Increase in Risk

Although not definitive, there are several plausible physiologic/embryologic mechanisms which may explain an association between preterm birth/pre-eclampsia and CV risk in offspring. The association in risk may be related to effects of the maternal condition on vascular development of the fetus while in the womb [135] and potentially mediated through alteration of endothelial function [136]. Part of the risk association may be related to effects on hypertension, which may manifest as early as a few days after birth in newborns of mothers with pre-eclampsia [137]. This may be related to alterations of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, with one study demonstrating higher aldosterone levels in male offspring of mothers with pre-eclampsia, however this association was attenuated when adjusted for BMI [138]. In one interesting study, preterm infants born to women (either with hypertension or who were normotensive) had higher blood pressures, however the underlying pathology differed between the two groups. Offspring of normotensive women born preterm had increased arterial stiffness, while offspring of hypertensive pregnancies had evidence of greater carotid intima-media thickness and lower flow mediated dilation [139]. Thus, the underlying pathology may differ although the subsequent expression of hypertension may be similar in childhood/adulthood. Additionally, there may be a common predisposition to vascular dysfunction passed from mother to child that could account for predisposition to risk [140–142].

Summary

Pregnancy is a time of significant hemodynamic and physiologic adaptations. These changes may bring to the surface conditions, such as the adverse pregnancy outcomes reviewed here, that may serve as markers of future risk. Infertility and adverse pregnancy outcomes and conditions such as preterm birth may also signify future CV maternal risk. In addition, the offspring of women with these conditions may also be at risk. In recent years, both the ACC/AHA and ESC have incorporated assessment of adverse pregnancy outcomes in recommendations regarding CV risk assessment [35, 143]. Obstetrics history should be included in every assessment of a female patient, and future studies should focus on integration of these risks into a scoring system to better risk-stratify these women. This is particularly important in young women who otherwise have few comorbidities but may be at higher, yet-unrecognized risk. In addition, it is important to assess this risk not only for the mother but for the potential health of the offspring. The evidence identifies a need for research in this area and highlights the importance of clinical recognition of these conditions and potential for future risk modification.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institutes nos. N01-HV-68161, N01-HV-68162, N01-HV-68163, N01-HV-68164, grants U0164829, U01 HL649141, U01 HL649241, K23HL105787, T32HL69751, T32HL116273, F31NR015725, R01 HL090957, 1R03AG032631 from the National Institute on Aging, GCRC grant MO1-RR00425 from the National Center for Research Resources, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1TR000124 and UL1TR000064, and grants from the Gustavus and Louis Pfeiffer Research Foundation, Danville, NJ, The Women’s Guild of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, The Ladies Hospital Aid Society of Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, PA, and QMED, Inc., Laurence Harbor, NJ, the Edythe L. Broad and the Constance Austin Women’s Heart Research Fellowships, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, the Barbra Streisand Women’s Cardiovascular Research and Education Program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, The Society for Women’s Health Research (SWHR), Washington, D.C., The Linda Joy Pollin Women’s Heart Health Program, and the Erika Glazer Women’s Heart Health Project, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Sharaf B, Wood T, Shaw L, et al. Adverse outcomes among women presenting with signs and symptoms of ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: findings from the national heart, lung, and blood institute-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE) angiographic core laboratory. Am Heart J. 2013;166:134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crea F, Camici PG, Bairey Merz CN. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: an update. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1101–11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pepine CJ. Multiple causes for ischemia without obstructive coronary artery disease: not a short list. Circulation. 2015;131:1044–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridker PM, Paynter NP, Rifai N, Gaziano JM, Cook NR. C-reactive protein and parental history improve global cardiovascular risk prediction: the Reynolds risk score for men. Circulation. 2008;118:2243–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goff DC, Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2935–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capeless EL, Clapp JF. Cardiovascular changes in early phase of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1449–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90902-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz R, Karliner JS, Resnik R. Effects of a natural volume overload state (pregnancy) on left ventricular performance in normal human subjects. Circulation. 1978;58:434–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.58.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robson SC, Hunter S, Boys RJ, Dunlop W. Serial study of factors influencing changes in cardiac output during human pregnancy. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:H1060–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robson SC, Hunter S, Moore M, Dunlop W. Haemodynamic changes during the puerperium: a Doppler and M-mode echocardiographic study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987;94:1028–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Oppen AC, Stigter RH, Bruinse HW. Cardiac output in normal pregnancy: a critical review. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:310–8. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fialova L, Malbohan I, Kalousova M, et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation in pregnancy. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2006;66:121–7. doi: 10.1080/00365510500375230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hastie CE, Smith GC, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Association between preterm delivery and subsequent C-reactive protein: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(556):e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brizzi P, Tonolo G, Esposito F, et al. Lipoprotein metabolism during normal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:430–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piechota W, Staszewski A. Reference ranges of lipids and apolipoproteins in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992;45:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(92)90190-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiznitzer A, Mayer A, Novack V, et al. Association of lipid levels during gestation with preeclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(482):e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butte NF, Hsu HW, Thotathuchery M, et al. Protein metabolism in insulin-treated gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:806–11. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Homko CJ, Sivan E, Reece EA, Boden G. Fuel metabolism during pregnancy. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1999;17:119–25. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1016219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Athukorala C, Rumbold AR, Willson KJ, Crowther CA. The risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women who are overweight or obese. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser A, Nelson SM, Macdonald-Wallis C, et al. Associations of pregnancy complications with calculated cardiovascular disease risk and cardiovascular risk factors in middle age: the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Circulation. 2012;125:1367–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rich-Edwards JW, Fraser A, Lawlor DA, Catov JM. Pregnancy characteristics and women’s future cardiovascular health: an underused opportunity to improve women’s health? Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:57–70. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010 data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Natl Health Stat Report. 2013:1–18. 1 p following 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messerlian C, Maclagan L, Basso O. Infertility and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:125–37. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy UM, Wapner RJ, Rebar RW, Tasca RJ. Infertility, assisted reproductive technology, and adverse pregnancy outcomes: executive summary of a national institute of child health and human development workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:967–77. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000259316.04136.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Haroush A, Yogev Y, Hod M. Epidemiology of gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004;21:103–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the fifth international workshop-conference on gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 2):S251–60. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in women with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2078–83. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Saydah S, et al. Trends in death rates among U.S. adults with and without diabetes between 1997 and 2006: findings from the national health interview survey. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1252–7. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunderson EP, Chiang V, Pletcher MJ, et al. History of gestational diabetes mellitus and future risk of atherosclerosis in mid-life: the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000490. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gobl CS, Bozkurt L, Yarragudi R, et al. Biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction in relation to impaired carbohydrate metabolism following pregnancy with gestational diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:138. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0138-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. Practice bulletin No. 137: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:406–16. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000433006.09219.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallis AB, Saftlas AF, Hsia J, Atrash HK. Secular trends in the rates of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, United States, 1987–2004. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:521–6. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American college of obstetricians and gynecologists’ task force on hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1122–31. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernandez-Diaz S, Toh S, Cnattingius S. Risk of pre-eclampsia in first and subsequent pregnancies: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b2255. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women–2011 update: a guideline from the American heart association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1404–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh JS, Cheng HM, Hsu PF, et al. Synergistic effect of gestational hypertension and postpartum incident hypertension on cardiovascular health: a nationwide population study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e001008. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J. 2008;156:918–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lykke JA, Langhoff-Roos J, Sibai BM, et al. Hypertensive pregnancy disorders and subsequent cardiovascular morbidity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the mother. Hypertension. 2009;53:944–51. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mongraw-Chaffin ML, Cirillo PM, Cohn BA. Preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease death: prospective evidence from the child health and development studies cohort. Hypertension. 2010;56:166–71. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romundstad PR, Magnussen EB, Smith GD, Vatten LJ. Hypertension in pregnancy and later cardiovascular risk: common antecedents? Circulation. 2010;122:579–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.943407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chambers JC, Fusi L, Malik IS, et al. Association of maternal endothelial dysfunction with preeclampsia. JAMA. 2001;285:1607–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.12.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, LaMarca BB, et al. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia: linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H541–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01113.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stekkinger E, Scholten R, van der Vlugt MJ, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the risk for recurrent pre-eclampsia: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120:979–86. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perng W, Stuart J, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Preterm birth and long-term maternal cardiovascular health. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davey Smith G, Hart C, Ferrell C, et al. Birth weight of offspring and mortality in the Renfrew and Paisley study: prospective observational study. BMJ. 1997;315:1189–93. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7117.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davey Smith G, Hypponen E, Power C, Lawlor DA. Offspring birth weight and parental mortality: prospective observational study and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:160–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaijser M, Bonamy AK, Akre O, et al. Perinatal risk factors for ischemic heart disease: disentangling the roles of birth weight and preterm birth. Circulation. 2008;117:405–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith GD, Whitley E, Gissler M, Hemminki E. Birth dimensions of offspring, premature birth, and the mortality of mothers. Lancet. 2000;356:2066–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kessous R, Shoham-Vardi I, Pariente G, Holcberg G, Sheiner E. An association between preterm delivery and long-term maternal cardiovascular morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(368):e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Catov JM, Dodge R, Barinas-Mitchell E, et al. Prior preterm birth and maternal subclinical cardiovascular disease 4 to 12 years after pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22:835–43. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Catov JM, Wu CS, Olsen J, et al. Early or recurrent preterm birth and maternal cardiovascular disease risk. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:604–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lykke JA, Paidas MJ, Damm P, et al. Preterm delivery and risk of subsequent cardiovascular morbidity and type-II diabetes in the mother. BJOG. 2010;117:274–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamilton BE, Hoyert DL, Martin JA, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2010–2011. Pediatrics. 2013;131:548–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58:1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bukowski R, Davis KE, Wilson PW. Delivery of a small for gestational age infant and greater maternal risk of ischemic heart disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu J, Barinas-Mitchell E, Kuller LH, Youk AO, Catov JM. Maternal hypertension after a low-birth-weight delivery differs by race/ethnicity: evidence from the national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999–2006. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hastie CE, Smith GC, Mackay DF, Pell JP. Maternal risk of ischaemic heart disease following elective and spontaneous pre-term delivery: retrospective cohort study of 750 350 singleton pregnancies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:914–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, Lie RT. Long term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2001;323:1213–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7323.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Catov JM, Dodge R, Yamal JM, et al. Prior preterm or small-for-gestational-age birth related to maternal metabolic syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:225–32. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182075626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Catov JM, Newman AB, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Parity and cardiovascular disease risk among older women: how do pregnancy complications mediate the association? Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:873–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Humphries KH, Westendorp IC, Bots ML, et al. Parity and carotid artery atherosclerosis in elderly women: the Rotterdam study. Stroke. 2001;32:2259–64. doi: 10.1161/hs1001.097224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lawlor DA, Emberson JR, Ebrahim S, et al. Is the association between parity and coronary heart disease due to biological effects of pregnancy or adverse lifestyle risk factors associated with child-rearing? Findings from the British women’s heart and health study and the British regional heart study. Circulation. 2003;107:1260–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000053441.43495.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ness RB, Harris T, Cobb J, et al. Number of pregnancies and the subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1528–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305273282104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Palmer JR, Rosenberg L, Shapiro S. Reproductive factors and risk of myocardial infarction. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:408–16. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Parikh NI, Cnattingius S, Dickman PW, et al. Parity and risk of later-life maternal cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2010;159:215–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parikh NI, Cnattingius S, Mittleman MA, Ludvigsson JF, Ingelsson E. Subfertility and risk of later life maternal cardiovascular disease. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:568–75. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kharazmi E, Dossus L, Rohrmann S, Kaaks R. Pregnancy loss and risk of cardiovascular disease: a prospective population-based cohort study (EPIC-Heidelberg) Heart. 2011;97:49–54. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.202226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Legro RS, Arslanian SA, Ehrmann DA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4565–92. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, et al. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2745–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stanczyk FZ. Diagnosis of hyperandrogenism: biochemical criteria. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20:177–91. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Apridonidze T, Essah PA, Iuorno MJ, Nestler JE. Prevalence and characteristics of the metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1929–35. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dokras A, Bochner M, Hollinrake E, et al. Screening women with polycystic ovary syndrome for metabolic syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:131–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000167408.30893.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ehrmann DA, Liljenquist DR, Kasza K, et al. Prevalence and predictors of the metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:48–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.DeUgarte CM, Bartolucci AA, Azziz R. Prevalence of insulin resistance in the polycystic ovary syndrome using the homeostasis model assessment. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1454–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dunaif A, Segal KR, Futterweit W, Dobrjansky A. Profound peripheral insulin resistance, independent of obesity, in polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes. 1989;38:1165–74. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.9.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Colilla S, Cox NJ, Ehrmann DA. Heritability of insulin secretion and insulin action in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and their first degree relatives. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2027–31. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ehrmann DA, Barnes RB, Rosenfield RL, Cavaghan MK, Imperial J. Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:141–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ehrmann DA, Kasza K, Azziz R, et al. Effects of race and family history of type 2 diabetes on metabolic status of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:66–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ehrmann DA, Sturis J, Byrne MM, et al. Insulin secretory defects in polycystic ovary syndrome. Relationship to insulin sensitivity and family history of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:520–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI118064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lo JC, Feigenbaum SL, Yang J, et al. Epidemiology and adverse cardiovascular risk profile of diagnosed polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1357–63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fogel RB, Malhotra A, Pillar G, et al. Increased prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1175–80. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tasali E, Van Cauter E, Ehrmann DA. Relationships between sleep disordered breathing and glucose metabolism in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:36–42. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vgontzas AN, Legro RS, Bixler EO, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness: role of insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:517–20. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Legro RS, Azziz R, Ehrmann D, et al. Minimal response of circulating lipids in women with polycystic ovary syndrome to improvement in insulin sensitivity with troglitazone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5137–44. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dunaif A. Prevalence and predictors of dyslipidemia in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Med. 2001;111:607–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00948-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boulman N, Levy Y, Leiba R, et al. Increased C-reactive protein levels in the polycystic ovary syndrome: a marker of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2160–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sprung VS, Atkinson G, Cuthbertson DJ, et al. Endothelial function measured using flow-mediated dilation in polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis of the observational studies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;78:438–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Birdsall MA, Farquhar CM, White HD. Association between polycystic ovaries and extent of coronary artery disease in women having cardiac catheterization. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:32–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-1-199701010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Christian RC, Dumesic DA, Behrenbeck T, et al. Prevalence and predictors of coronary artery calcification in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2562–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Talbott EO, Guzick DS, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Evidence for association between polycystic ovary syndrome and premature carotid atherosclerosis in middle-aged women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2414–21. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang ET, Cirillo PM, Vittinghoff E, et al. Menstrual irregularity and cardiovascular mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E114–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de Groot PC, Dekkers OM, Romijn JA, Dieben SW, Helmerhorst FM. PCOS, coronary heart disease, stroke and the influence of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:495–500. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wild S, Pierpoint T, McKeigue P, Jacobs H. Cardiovascular disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome at long-term follow-up: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000;52:595–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, et al. Menstrual cycle irregularity and risk for future cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2013–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jovanovic VP, Carmina E, Lobo RA. Not all women diagnosed with PCOS share the same cardiovascular risk profiles. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:826–32. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pierpoint T, McKeigue PM, Isaacs AJ, Wild SH, Jacobs HS. Mortality of women with polycystic ovary syndrome at long-term follow-up. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:581–6. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Udell JA, Lu H, Redelmeier DA. Long-term cardiovascular risk in women prescribed fertility therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1704–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kallen B, Finnstrom O, Nygren KG, Otterblad Olausson P, Wennerholm UB. In vitro fertilisation in Sweden: obstetric characteristics, maternal morbidity and mortality. BJOG. 2005;112:1529–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Venn A, Hemminki E, Watson L, Bruinsma F, Healy D. Mortality in a cohort of IVF patients. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2691–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.12.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N, Cook NR. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: the Reynolds risk score. JAMA. 2007;297:611–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stuart JJ, Bairey Merz CN, Berga SL, et al. Maternal recall of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: a systematic review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22:37–47. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Visentin S, Grumolato F, Nardelli GB, et al. Early origins of adult disease: low birth weight and vascular remodeling. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:391–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fowden AL, Giussani DA, Forhead AJ. Intrauterine programming of physiological systems: causes and consequences. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:29–37. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00050.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leeson CP, Whincup PH, Cook DG, et al. Flow-mediated dilation in 9- to 11-year-old children: the influence of intrauterine and childhood factors. Circulation. 1997;96:2233–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Napoli C, D’Armiento FP, Mancini FP, et al. Fatty streak formation occurs in human fetal aortas and is greatly enhanced by maternal hypercholesterolemia. Intimal accumulation of low density lipoprotein and its oxidation precede monocyte recruitment into early atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2680–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI119813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Napoli C, Witztum JL, de Nigris F, et al. Intracranial arteries of human fetuses are more resistant to hypercholesterolemia-induced fatty streak formation than extracranial arteries. Circulation. 1999;99:2003–10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.15.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Napoli C, Infante T, Casamassimi A. Maternal-foetal epigenetic interactions in the beginning of cardiovascular damage. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;92:367–74. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bonamy AK, Kallen K, Norman M. High blood pressure in 2.5-year-old children born extremely preterm. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1199–204. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hovi P, Andersson S, Eriksson JG, et al. Glucose regulation in young adults with very low birth weight. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2053–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Johansson S, Iliadou A, Bergvall N, et al. Risk of high blood pressure among young men increases with the degree of immaturity at birth. Circulation. 2005;112:3430–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ueda P, Cnattingius S, Stephansson O, et al. Cerebrovascular and ischemic heart disease in young adults born preterm: a population-based Swedish cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:253–60. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9892-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Abitbol CL, Rodriguez MM. The long-term renal and cardiovascular consequences of prematurity. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:265–74. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bonamy AK, Martin H, Jorneskog G, Norman M. Lower skin capillary density, normal endothelial function and higher blood pressure in children born preterm. J Intern Med. 2007;262:635–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cheung YF, Wong KY, Lam BC, Tsoi NS. Relation of arterial stiffness with gestational age and birth weight. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:217–21. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.025999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oren A, Vos LE, Bos WJ, et al. Gestational age and birth weight in relation to aortic stiffness in healthy young adults: two separate mechanisms? Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:76–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(02)03151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tauzin L, Rossi P, Giusano B, et al. Characteristics of arterial stiffness in very low birth weight premature infants. Pediatr Res. 2006;60:592–6. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000242264.68586.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jaddoe VW, de Jonge LL, Hofman A, et al. First trimester fetal growth restriction and cardiovascular risk factors in school age children: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bonamy AK, Bendito A, Martin H, et al. Preterm birth contributes to increased vascular resistance and higher blood pressure in adolescent girls. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:845–9. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000181373.29290.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Higgins M, Keller J, Moore F, et al. Studies of blood pressure in Tecumseh, Michigan. I. Blood pressure in young people and its relationship to personal and familial characteristics and complications of pregnancy in mothers. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;111:142–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Langford HG, Watson RL. Prepregnant blood pressure, hypertension during pregnancy, and later blood pressure of mothers and offspring. Hypertension. 1980;2:130–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Palti H, Rothschild E. Blood pressure and growth at 6 years of age among offsprings of mothers with hypertension of pregnancy. Early Hum Dev. 1989;19:263–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(89)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Seidman DS, Laor A, Gale R, et al. Pre-eclampsia and offspring’s blood pressure, cognitive ability and physical development at 17-years-of-age. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98:1009–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb15339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tenhola S, Rahiala E, Halonen P, Vanninen E, Voutilainen R. Maternal preeclampsia predicts elevated blood pressure in 12-year-old children: evaluation by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:320–4. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000196734.54473.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fraser A, Nelson SM, Macdonald-Wallis C, Sattar N, Lawlor DA. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and cardiometabolic health in adolescent offspring. Hypertension. 2013;62:614–20. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Davis EF, Lazdam M, Lewandowski AJ, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in children and young adults born to preeclamptic pregnancies: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1552–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kajantie E, Eriksson JG, Osmond C, Thornburg K, Barker DJ. Pre-eclampsia is associated with increased risk of stroke in the adult offspring: the Helsinki birth cohort study. Stroke. 2009;40:1176–80. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.538025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ceelen M, van Weissenbruch MM, Vermeiden JP, van Leeuwen FE, de Waal HAD-v. Cardiometabolic differences in children born after in vitro fertilization: follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1682–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Scherrer U, Rimoldi SF, Rexhaj E, et al. Systemic and pulmonary vascular dysfunction in children conceived by assisted reproductive technologies. Circulation. 2012;125:1890–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.071183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Valenzuela-Alcaraz B, Crispi F, Bijnens B, et al. Assisted reproductive technologies are associated with cardiovascular remodeling in utero that persists postnatally. Circulation. 2013;128:1442–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nastri CO, Ferriani RA, Rocha IA, Martins WP. Ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome: pathophysiology and prevention. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:121–8. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9387-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Xu GF, Zhang JY, Pan HT, et al. Cardiovascular dysfunction in offspring of ovarian-hyperstimulated women and effects of estradiol and progesterone: a retrospective cohort study and proteomics analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E2494–503. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Torrens C, Snelling TH, Chau R, et al. Effects of pre- and periconceptional undernutrition on arterial function in adult female sheep are vascular bed dependent. Exp Physiol. 2009;94:1024–33. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.047340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Norman M. Low birth weight and the developing vascular tree: a systematic review. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:1165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Reveret M, Boivin A, Guigonnis V, Audibert F, Nuyt AM. Preeclampsia: effect on newborn blood pressure in the 3 days following preterm birth: a cohort study. J Hum Hypertens. 2015;29:115–21. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2014.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Washburn LK, Brosnihan KB, Chappell MC, et al. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in adolescent offspring born prematurely to mothers with preeclampsia. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1470320314526940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Lazdam M, de la Horra A, Pitcher A, et al. Elevated blood pressure in offspring born premature to hypertensive pregnancy: is endothelial dysfunction the underlying vascular mechanism? Hypertension. 2010;56:159–65. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Davis EF, Newton L, Lewandowski AJ, et al. Pre-eclampsia and offspring cardiovascular health: mechanistic insights from experimental studies. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;123:53–72. doi: 10.1042/CS20110627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Geelhoed JJ, Fraser A, Tilling K, et al. Preeclampsia and gestational hypertension are associated with childhood blood pressure independently of family adiposity measures: the avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Circulation. 2010;122:1192–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.936674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Jayet PY, Rimoldi SF, Stuber T, et al. Pulmonary and systemic vascular dysfunction in young offspring of mothers with pre-eclampsia. Circulation. 2010;122:488–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.941203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Blomstrom Lundqvist C, Borghi C, et al. ESC guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the task force on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy of the European society of cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:3147–97. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]