Abstract

Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer is a highly valued medicinal plant. Cylindrocarpon destructans is a destructive pathogen that causes root rot and significantly reduces the quality and yield of P. ginseng. However, an efficient method to control root rot remains unavailable because of insufficient understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying C. destructans-P. ginseng interaction. In this study, C. destructans-induced transcriptomes at different time points were investigated using RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). De novo assembly produced 73,335 unigenes for the P. ginseng transcriptome after C. destructans infection, in which 3,839 unigenes were up-regulated. Notably, the abundance of the up-regulated unigenes sharply increased at 0.5 d postinoculation to provide effector-triggered immunity. In total, 24 of 26 randomly selected unigenes can be validated using quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR. Gene ontology enrichment analysis of these unigenes showed that “defense response to fungus”, “defense response” and “response to stress” were enriched. In addition, differentially expressed transcription factors involved in the hormone signaling pathways after C. destructans infection were identified. Finally, differentially expressed unigenes involved in reactive oxygen species and ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway during C. destructans infection were indentified. To our knowledge, this study is the first to report on the dynamic transcriptome triggered by C. destructans. These results improve our understanding of disease resistance in P. ginseng and provide a useful resource for quick detection of induced markers in P. ginseng before the comprehensive outbreak of this disease caused by C. destructans.

Introduction

Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer of the Araliaceae family of perennial plants is a highly valued medicinal plant that is native to East Asian countries such as China, Korea, and Japan [1]. For thousands of years, P. ginseng root has been widely used as a traditional medicine to promote vitality, enhance physical performance, and increase resistance to stress and aging [2]. However, P. ginseng production requires a five- to six-year cultivation period, which results in a long exposure to soilborne pathogens. The accumulation of Cylindrocarpon destructans, a destructive pathogen present in the ginseng rhizosphere soil, causes serious root rot disease in P. ginseng and significantly decreases the quality and yield of P. ginseng [3]. C. destructans may survive in soil for over 10 years, thereby complicating the control of root rot [4]. The accumulation of soilborne pathogens and allelochemicals in P. ginseng cultivating fields prevents the continuous cultivation of P. ginseng. In addition, commercial fungicides exert limited effects on controlling P. ginseng root rot caused by C. destructans [3]. Furthermore, effective and environment-friendly biocontrol agents or resistant P. ginseng cultivars are currently unavailable. Hence, detection of the change of C. destructans-induced markers at early stage and taking measures in advance was important to ensure the high yield and quality of P. ginseng.

Previous study shown that C. destructans can also cause disease symptoms on roots in other species, such as strawberry [5, 6] and grapevines [7, 8]. Comparing with the retarding development in strawberry, C. destructans may cause severely root rot symptom, and finally resulted in the death of P. ginseng. Moreover, understanding the molecular mechanism underlying P. ginseng root rot is necessary to effectively control this disease in the field. Researchers studied the genetic diversity and pathogenicity of C. destructans [4, 9]. However, the P. ginseng transcriptome during C. destructans infection and the molecular mechanism of infection-response underlying C. destructans-P. ginseng interaction remain unknown. Gene expression profiling after pathogen infection elucidates plant-pathogen interactions. The current study aims to determine the response of P. ginseng to C. destructans infection to reveal defense-related unigenes involved in the plant-pathogen interaction. To achieve this objective, time-course transcriptome libraries were sequenced using Solexa/Illumina RNA-Seq technology to produce high-quality assembly sequences for further quantitative expression analysis. Important differentially expressed transcription factors (TFs) involved in the hormone signaling pathways during disease infection were also identified. Results showed that the unigenes involved in pathogen infection response were dramatically up-regulated at 0.5 d postinoculation (DPI). This study not only revealed pathogen-responsive unigenes for further functional research on accelerating disease-resistant breeding but also provided candidate genes for early detection of induced markers in P. ginseng to prevent the comprehensive outbreak of root rot disease caused by C. destructans.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Roots of three-year-old P. ginseng cv. Damaya were collected from the experimental field of the Institute of Medicinal Plant Development, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. No specific permits were required for the described field studies. The P. ginseng chosen in this study is susceptible to C. destructans infection. Healthy P. ginseng roots were sterilized using 50% carbendazol wettable powder (diluted 800 times) for 10 min and then rinsed thrice in distilled water. The plants were transplanted into sterilized silica sand in plastic square pots (40 cm × 20 cm × 15 cm) with a density of 48 plants/pot and placed in a greenhouse under a 16 h/8 h light/dark cycle at 25°C to control soil moisture, temperature, fertility, pathogens, and other unpredictable factors that may influence disease severity and pathogen growth [10]. Hoagland nutrient solution [11] was used to provide essential nutrients for the normal growth of the P. ginseng plants.

Inoculation with C. destructans and RNA extraction

C. destructans was inoculated and cultured in liquid potato dextrose medium at 25°C on a shaking incubator for 7 d. Subsequently, spore concentrations were observed with a hemocytometer. After the leaves of the plants fully spread, 250 ml of C. destructans spore suspension (4.3 × 106 condia·ml−1) was sprayed to each pot of sterilized silica sand so that C. destructans could be adsorbed by roots of P. ginseng evenly. The polysaccharide content in the main root of P. ginseng was extremely high, and fibrous roots of P. ginseng have stronger response to pathogen infection than the main root. Thus, fibrous roots of P. ginseng from three plants were collected and pooled for RNA extraction to ensure the quality for high-throughput sequencing. Time-course disease responses were investigated at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 4, 7, and 12 DPI. The fibrous roots harvested from the uninfected P. ginseng plants served as controls (0 DPI). The fibrous roots of three plants at each time point were rinsed with distilled water and then pooled. The roots were briefly blotted with several pieces of dry filter paper and then immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until RNA extraction. The total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols and then treated with RNase-free DNase to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The total RNA for RNA-Seq library construction was quantified on the Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE) and the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Santa Clara, CA).

Library construction and sequencing

Transcriptome libraries were constructed using the Illumina kit in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the total RNA treated with DNase was purified and isolated using Magnetic Oligo (dT) beads. Then, the purified RNA was sheared to approximately 330 nt fragments prior to cDNA synthesis. Short fragments were purified and ligated to sequencing adapters. Fragments with suitable sizes (400–500 nt) on the basis of agarose gel electrophoresis were selected as templates for PCR amplification in order to isolated and purify the cDNA fragments for sequencing. The final PCR products were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq™ 2000 as 100 nt paired-end (PE) Illumina reads. The quality of raw RNA-Seq reads was filtered using the following criteria: (1) reads including adapter sequencing or empty adapter were filtered; (2) reads for which Ns comprised more than 3% of the total length were discarded; and (3) reads including low-quality bases that comprise more than 15% of the total reads were discarded.

Transcriptome assembly and annotation

The RNA-Seq reads were subjected to de novo transcriptome assembly by using Trinity assembly software [12] to obtain high-quality transcript sequences. Large RNA-Seq datasets were normalized using the Trinity in silico normalization utility. Then, PE RNA-Seq reads with default parameters were subjected to de novo transcriptome assembly by using Trinity (version: r20140413p1). Transdecoder with the default parameters was used to identify open reading frames [13]. Then, the assembled sequences were used for a homology search against the UniProt databases by ncbi-blast-2.2.27+ with an E-value of 10−6. Gene ontology (GO) terms were assigned to assemble the sequences on the basis of the UniProt databases (EMBL Uniprot eggNOG/GO pathways databases). GO terms were analyzed to classify the unigenes into biological process, cellular component, and molecular function. GO enrichment analysis (P < 0.05; hypergeometric test with Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate correction) was performed on selected unigenes using BINGO 3.0.2 [14] in accordance with the custom GO annotation files to identify the enriched GO terms.

Identification of C. destructans sequences

C. destructans EST sequences were downloaded from the NCBI EST database. Assembly sequences of C. destructans were identified using ncbi-blast-2.2.27+ with more than 90% identity and E-value less than 0.00001.

Gene expression analysis

Bowtie2 2.2.3 [12] was used to map the RNA-Seq reads with the assembled sequences to calculate the read counts for each unigene. Only PE reads paired with unique locations were retained to accurately calculate the expression values of the assembled unigenes. The transcript levels of each unigene were measured and normalized as the fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM), which is analogous to reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads [15]. Unigenes with low expression have questionable biological significance and are difficult to validate. Therefore, in this study, the minimum expression threshold for FPKM > 3 was observed in at least one library. The P value was assessed using an MA-plot-based method with the random sampling model in the statistical R package DEGseq [16]. Then, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were filtered at a fold change > 3 and a P < 0.001 (Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate correction) as the threshold by performing pair-wise comparisons of infected samples with noninfected samples. The clustering algorithm was used to analyze time-course gene expression data [17].

Validation of DEGs and defense-related genes through quantitative reverse transcription (qRT) PCR

RNA for qRT-PCR validation was extracted from fibrous roots of P. ginseng as a different set of biological samples under the same condition as that used in RNA-Seq. The extracted RNA was digested with RNase-free DNase I (Promega) to remove genomic DNA contamination. Reverse transcription was performed using 1 μg of total RNA for each example and 200 U M-MLV Transcriptase (TaKaRa) in a 10 μl volume. The reaction was conducted at 70°C for 10 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 70°C for 15 min. The resulting cDNA was diluted to 800 μl with sterile water. qPCR was conducted using the BIO-RAD CFX system (BIO-RAD) in triplicate. Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3/). The primers used in this study are listed in S1 Table. An eEF-1α gene (c64517_g1) was selected as the endogenous control because of its relatively stable mRNA across all the time points. PCR was conducted in a 20 μl volume containing 4 μl of diluted cDNA, 250 nM forward primer, 250 nM reverse primer, and 1 × SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa) under the following conditions: 95°C for 3 min and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 59°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s. Melting curve analyses were performed to verify the specificity of the Bio-Rad CFX Manager software. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method [18].

Identification of disease RGs

To identify RGs in P. ginseng, manually curated reference RGs were downloaded from the Plant Resistance Gene Database (PRGdb, http://prgdb.crg.eu/). BLAST with a stringent E-value cutoff of 10−15 was used to identify homologous sequences in the P. ginseng assembly transcriptome.

Results

Sequencing and de novo assembly of the P. ginseng transcriptome

The innate immune responses of P. ginseng to C. destructans infection were explored by constructing RNA-Seq libraries for 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 4, 7, and 12 DPI to maximize the transcript diversity and by sequencing these libraries using the Illumina/Solexa high-throughput sequencing platform (Table 1). After removing low-quality reads, 27, 27, 28, 26, 23, 27, and 29 million 100 bp PE clean reads were generated from one control and six treatments (Table 1). More than 180 million 100 nt PE reads were ultimately generated. All of the sequencing reads are available in the Short Read Archive database under Accession Number SRR1639601.

Table 1. Summary of Illumina sequencing and transcriptome assemblies for RNA-Seq libraries.

| Sample | Reads (PE) | Length | Total bases (×100bp) | GC%a | Mapping (ratio) | Unique | FPKM >3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 DPI | 27,086,424×2 | 100,100 | 54,172,848 | 43,43 | 45,396,150 (84%) | 18,770,088×2 | 20,298 |

| 0.5 DPI | 27,961,332×2 | 100,100 | 55,922,664 | 43,43 | 47,263,043 (85%) | 19,721,325×2 | 19,385 |

| 1 DPI | 26,009,438×2 | 100,100 | 52,018,876 | 43,43 | 44,250,820 (85%) | 18,602,589×2 | 19,789 |

| 4 DPI | 23,420,903×2 | 100,100 | 46,841,806 | 43,43 | 39,345,176 (84%) | 16,267,657×2 | 20,543 |

| 7 DPI | 27,215,622×2 | 100,100 | 54,431,244 | 43,44 | 45,964,650 (84%) | 20,190,441×2 | 20,104 |

| 12 DPI | 28,951,315×2 | 100,100 | 57,902,630 | 43,43 | 47,795,838 (83%) | 19,968,169×2 | 21,123 |

The P. ginseng plant genome sequence is currently unavailable; therefore, de novo transcriptome assembly was adopted before calculating the expression level. PE reads from different libraries were assembled into transcript sequences by using Trinity [13]. De novo assembly yielded 73,335 unigenes for the P. ginseng transcriptome after C. destructans infection. The average length for the assembled sequence was 1,385 bp, suggesting that the quality of the assembly was high enough to conduct downstream analyses. We blasted the Trinity assembly with C. destructans EST sequences and found only 10 assembly sequences that were similar to C. destructans sequences. We excluded this small amount of C. destructans sequences before the downstream analysis.

Gene expression analysis

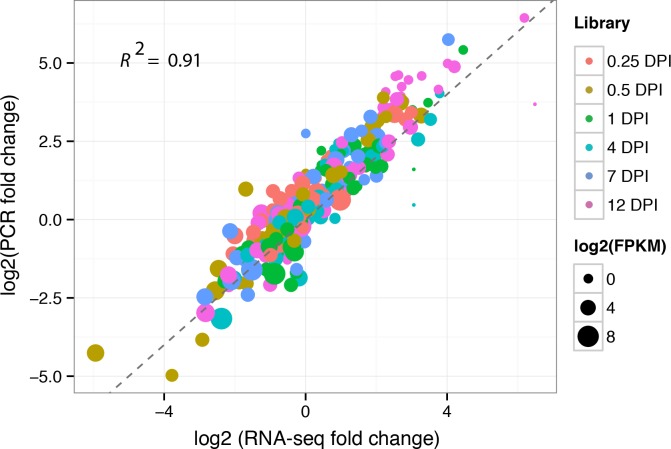

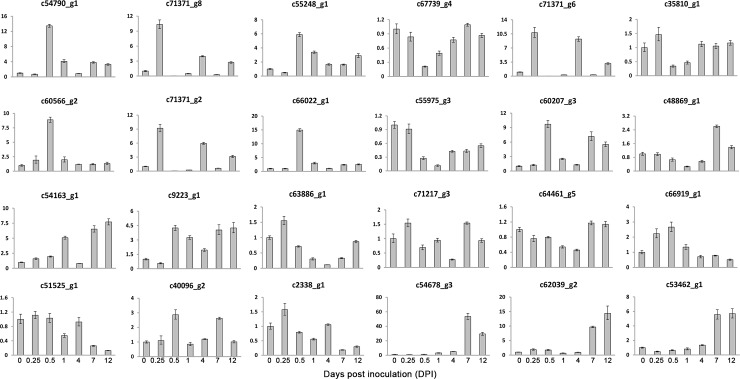

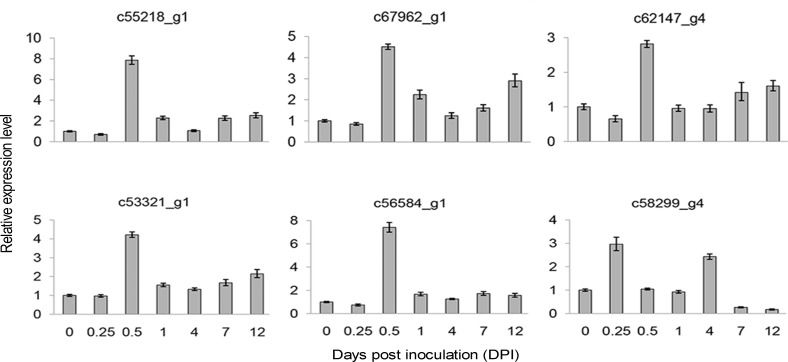

Approximately 84% of the reads were successfully mapped to the assembled transcript sequences by using Bowtie2 [12] alignment (Table 1). The ratio of matched reads was not significantly different. A total of 46,616,140, 37,540,176, 39,442,650, 37,205,178, 32,535,314, 40,380,882, and 39,936,338 reads were mapped in pairs with unique locations for the libraries of 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 4, 7, and 12 DPI, respectively (Table 1). Gene expression levels were measured and normalized as FPKM to quantify the expression of each unigene [15]. Only PE reads paired with a unique location were retained to accurately calculate the expression values of the assembled unigenes. The unigenes with high expression values included anti-sense ribosomal RNA transcript protein 2 (c71357_g1), phloem protein 2-like A4 (c59751_g4), omega-6 fatty acid desaturase (c69775_g1), auxin-repressed 12.5 kD protein (c50590_g1), ribonuclease 2 (c61159_g1), and heat shock cognate protein 80 (c60763_g1). Ribonuclease 2 [19] and shock cognate protein 80 [20] responded to biotic stimuli and stress, respectively. In total, 19524, 20298, 19385, 19789, 20543, 20104, and 21123 unigenes were expressed in the libraries of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 4, 7, and 12 DPI, respectively (Table 1), with corresponding average FPKMs of 27, 28, 27, 27, 28, and 26. We randomly selected 26 unigenes and performed qRT-PCR analysis with specific primers at seven time points to validate the reliability of the RNA-Seq results. In order to further validate the reliability of our RNA-seq result, we also selected 24 unigenes that shown differential expression in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway. At the same time, six defense response genes were also selected for validation. In total, we validated 56 genes in this study by qRT-PCR. The correlation coefficient for these unigenes was 0.91, which indicating a high correlation between qRT-PCR and RNA-Seq results (Fig 1). The experiment validation based on qRT-PCR suggested that the results of RNA-Seq were solid. The expression patterns of the 24 randomly selected unigenes (92%) identified by RNA-Seq can be validated using qRT-PCR (Fig 2) and the expression trends of RNA-Seq were shown at S1 Fig. The validation results by qRT-PCR for 24 DEGs from ROS and ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway were presented at S2 Fig.

Fig 1. Correlation between qRT-PCR and RNA-Seq.

The X-axis represents the log2 fold change of RNA-Seq. The Y-axis indicates the log2 value of fold change from qRT-PCR. Different colors represent different time points. The size of each point is proportional to the log2 (FPKM) in 0 DPI.

Fig 2. Validation of 24 randomly selected genes through qRT-PCR.

Fold changes of the transcript levels at different time points are shown. The average expression level at 0 DPI was set to 1. Error bars represent standard error from three independent experimental replicates.

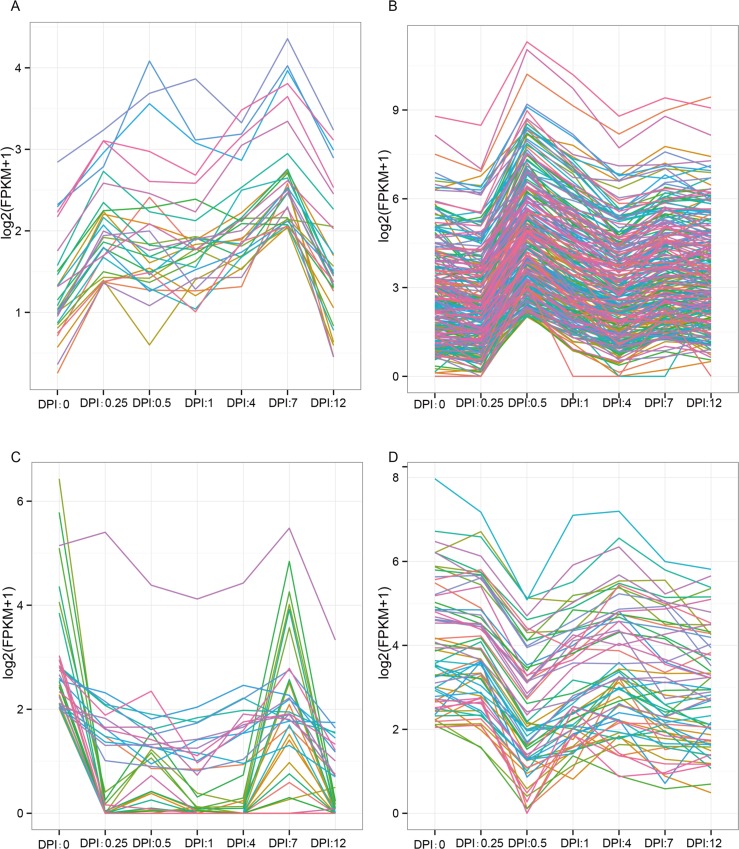

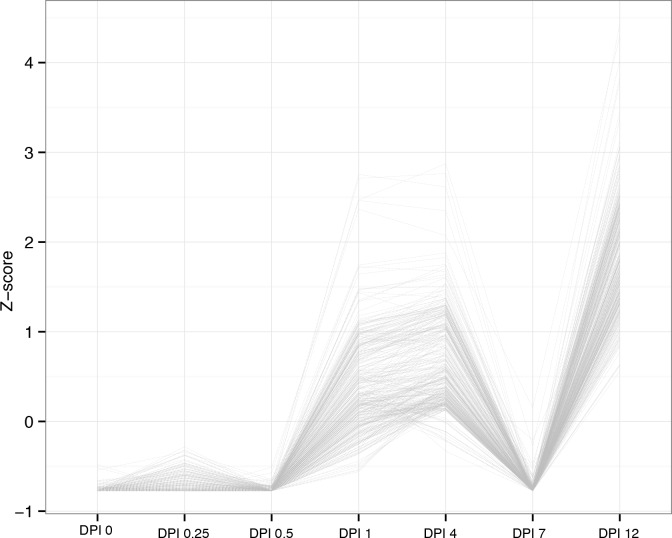

Cluster of time-course RNA-Seq data

Normalized FPKMs were provided as input for Short Time-series Expression Miner analysis [17]. An expression matrix was constructed, and the groups of unigenes that varied in concert over different time points were revealed. Unigenes sharing similar expression patterns were clustered, and the most statistically significant profiles were identified (Fig 3). The expression level of some of the unigenes increased at 0.25 DPI, decreased between 0.5 DPI and 4 DPI, and then slightly increased at 7 DPI (Fig 3A). In addition, the expression pattern of most of the up-regulated unigenes rapidly increased at 0.5 DPI (Fig 3B). Notably, the abundance of the up-regulated unigenes sharply increased at 0.5 DPI. The expression level of some of the down-regulated unigenes decreased at 0.25 DPI and then increased at 7 DPI (Fig 3C). The expression profile of most of the down-regulated unigenes sharply decreased at 0.5 DPI (Fig 3D). Considerable expression changes were observed at 0.5 DPI, suggesting that the unigenes related to defense response to fungus served important functions at this time point.

Fig 3. Most represented patterns of time-course data for DEGs.

Unigene expression profiles are clustered using the Short Time-series Expression Minor program. The y-axes represent expression level and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection. A) Expression increased at 0.25 DPI relative to the 0 DPI. In the middle stage, the expression of part genes decreased and then slightly increased at 7 DPI. B) The expression pattern of most of the unigenes rapidly increased at 0.5 DPI relative to the 0 and 0.25 DPI, and then decreased at 4 DPI. At 7 DPI there were slightly increased. C) The expression of part down-regulated unigenes decreased at 0.25 DPI and then remained at low level from 0.5 DPI to 4 DPI. At last two stages the unigenes sharply increased at 7 DPI and sharply decreased at 12 DPI. D) The expression of the down-regulated unigenes sharply decreased at 0.5 DPI relative to the 0 DPI, then other stage maintained relative stable expression.

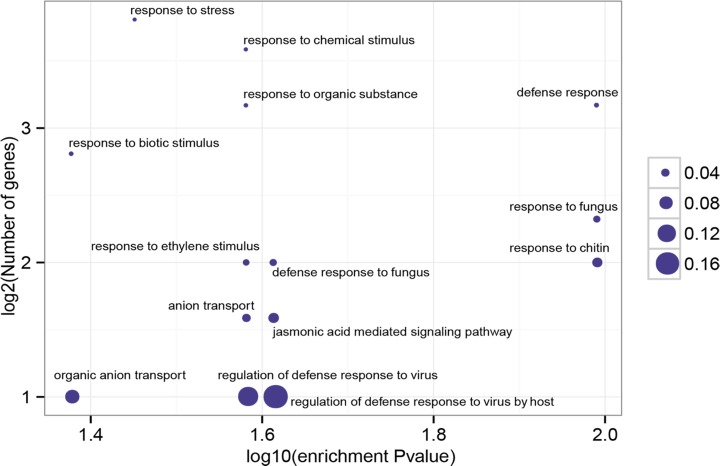

DEG identification and GO functional enrichment analysis for DEGs

The ultimate goal of this study is to characterize the dynamic changes in the P. ginseng transcriptome after C. destructans infection. Thus, the DEGs in P. ginseng plants infected by C. destructans were investigated. To identify significant DEGs, a cutoff of at least a three-fold change and P < 0.001 was used. In total, 81, 538, 392, 513, 606, and 2,845 up-regulated unigenes as well as 99, 201, 76, 69, 191, and 280 down-regulated unigenes were identified from the libraries of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 4, 7, and 12 DPI, respectively (Table 2). GO analysis for up-regulated unigenes showed that “defense response to fungus” was enriched (P = 1.0250E-2). All of the significant GO terms for DEGs were shown in Fig 4. Enrichment of “jasmonic acid mediated signaling pathway” was correlated well with the previous report that jasmonic acid (JA)-responsive genes are involved in defense response [21]. In total there were seven up-regulated unigenes (c53321_g1, c53833_g1, c55218_g1, c56156_g1, c57783_g2, c60188_g4, c71320_g4) that were involved in the jasmonic acid mediated signaling pathway. The expression of these seven JA related genes increased at 0.5 DPI, suggesting that these genes were induced to obtain systemic resistance at this time point by JA-mediated signaling pathway. “Response to ethylene stimulus” was also enriched in the up-regulated genes. In total there were 13 ethylene related genes identified in the up-regulated genes. These genes were involved in ethylene binding (c67746_g1), ethylene biosynthetic process (c67590_g1 and c59280_g1), ethylene-activated signaling pathway (c53833_g1, c57684_g3, c60188_g4, c61349_g2, c62289_g1, c62289_g2 and c62382_g3), negative regulation of ethylene-activated signaling pathway (c67746_g1), response to ethylene (c54969_g1 and c55218_g1) and ethylene-dependent systemic resistance (c62382_g3 and c67174_g2). It will be interesting to investigate the unigenes with ethylene-dependent systemic resistance in future. The enriched GO terms for the down-regulated unigenes differed from those for the up-regulated unigenes. GO terms associated with “photosynthesis” “carbon fixation”, “photosystem II stabilization”, “red light signaling pathway” and “paclitaxel biosynthetic process” were enriched for the down-regulated unigenes. The above results suggested that the root rot pathogen C. destructans affected the photosynthesis of the host plant P. ginseng. Consistently, a previous study reported that leaves infected by foliar pathogens exhibit reduced photosynthetic activity [22]. All identified differentially expressed unigenes with GO annotation were listed in S2 Table. These results provided a comprehensive overview of gene expression and valuable information for further investigation.

Table 2. The number of up- and down-regulated DEGs based on pair-wise comparison with control (fold change > 3; P < 0.001).

| Sample | Up-regulated | Down-regulated |

|---|---|---|

| 0.25 DPI | 81 | 99 |

| 0.5 DPI | 538 | 201 |

| 1 DPI | 392 | 76 |

| 4 DPI | 513 | 69 |

| 7 DPI | 606 | 191 |

| 12 DPI | 2,845 | 280 |

Fig 4. Significant enrichment functional groups of DEGs.

The most significant GO terms (P < 0.05) of differentially expressed unigenes are graphically presented by comparing with total transcripts. The x-axis represents log10 of the enrichment P value. The y-axis indicates the number of unigenes in log2 value. The size of each point is proportional to the percentage (DEG associated with GO terms/All unigenes associated with GO terms).

In order to reveal the dynamic change along the development of infection, we added all the possible combinations and comprising analysis among all the different time points. In total, there were 2,494 up-regulated and 4,526 down-regulated genes (Table 3), respectively. Among these DEGs from new comparisons, we identified one expression patterns that slightly increased at 0.25 DPI, and then presented low expression at 0.5 DPI and 7 DPI (Fig 5). Notably, the abundance of the DEGs sharply increased at 1 DPI, 4 DPI and 12 DPI, respectively. The enriched GO terms for these unigenes associated with “cell cycle process”, “translation” and “transmembrane transport”, which suggested that C. destructans affected the cell cycle and protein translation of the host plant P. ginseng at middle and later stage.

Table 3. Summary of comparisions among all the time points (fold change > 3; P < 0.001).

| Pair-wise Comparision | Up | Down |

|---|---|---|

| 0.25 vs. 0.5 | 643 | 256 |

| 0.25 vs. 1 | 548 | 172 |

| 0.25 vs. 4 | 571 | 92 |

| 0.25 vs. 7 | 645 | 316 |

| 0.25 vs. 12 | 3,002 | 509 |

| 0.5 vs. 1 | 352 | 114 |

| 0.5 vs. 4 | 624 | 416 |

| 0.5 vs. 7 | 725 | 494 |

| 0.5 vs. 12 | 2,808 | 584 |

| 1 vs. 4 | 252 | 170 |

| 1 vs. 7 | 530 | 460 |

| 1 vs. 12 | 2,734 | 292 |

| 4 vs. 7 | 465 | 610 |

| 4 vs. 12 | 2,616 | 249 |

| 7 vs. 12 | 2,436 | 492 |

Fig 5. Most represented patterns of time-course data for other comparisions.

The y-axes represent Z-score and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

Defense response analyses

Unigenes involved in defense response or pathogenesis (GO: 0006952 and GO: 0009405) were further analyzed. In total, 257 defense response unigenes (DRG) were identified, of which 29 (11% of the total) showed differential expression. The expression profiles of six representative DRGs were validated at different time points by using qRT-PCR (Fig 6). As shown in S3 Fig, qRT-PCR and RNA-Seq analyses revealed consistent expression trends of the DRGs. TFs are important components involved in the interaction between plants and microbes as well as in the regulation of defense-related genes [23]. Among the 29 DEGs, TFs ethylene-responsive transcription factor 2 (c60188_g4), TIFY 10A (c53321_g1), TIFY 10B (c69797_g3), and MYB108 (c55218_g1 and c54969_g1) increased at 0.5 DPI compared with the control. JA is the primary signaling molecule that regulates pathogen resistance in plants [24]. Genes related to the JA pathway are induced by pathogen attack [25]. TIFY 10A and TIFY 10B respond to the JA-mediated signaling pathway [26–28]. These results indicated the existence of a crosstalk for DEGs in response to resistance and hormone in P. ginseng. Pathogenesis-related protein (PRP) is important in the defense mechanism of P. ginseng and is up-regulated under biotic stress [29]. In the present study, two PRP unigenes (c55244_g1 and c58299_g4) were differentially expressed after C. destructans infection (S4 Fig).

Fig 6. Expression profiles of six randomly selected RGs through qRT-PCR.

Fold changes of the transcript levels at different time points are shown. The average expression level at 0 DPI was set to 1. Error bars represent standard error.

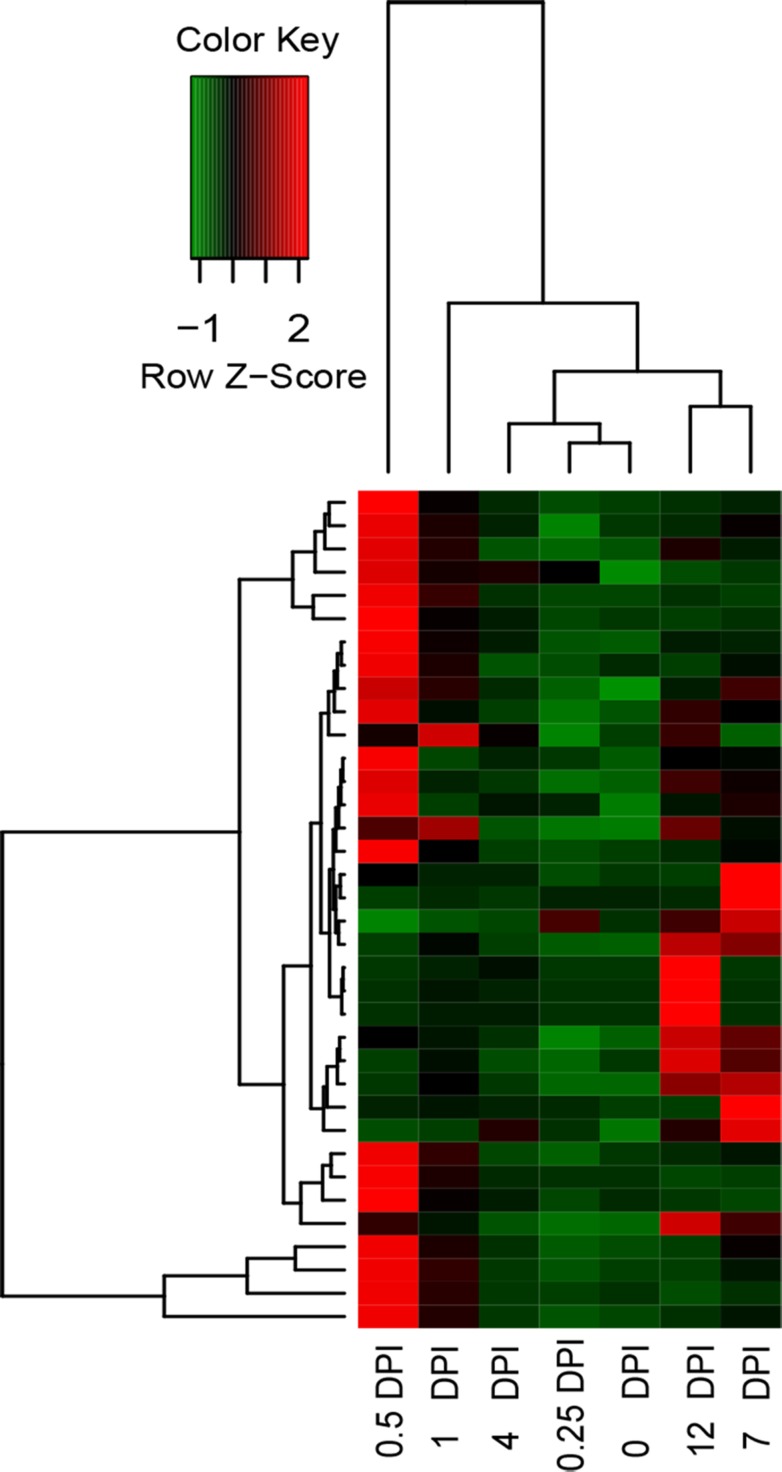

RG expression profiling

Basing on the PRGdb database, we matched 1040 unigenes in P. ginseng with the reference RGs. The low expression levels of the 36 RGs in the control increased (fold change > 3) after C. destructans infection in at least one DPI library (S5 Fig). In addition, 0.5 DPI was the time point at which P. ginseng response to C. destructans infection was dramatically induced (Fig 7). All identified RGs with FPKM and annotation are listed in S3 Table.

Fig 7. Heatmap showing the FPKM values of up-regulated RGs.

The FPKM for the RGs in the control and six infected stages was used for hierarchical analysis. The heatmap shows the expression abundance of the RGs. The colors correspond to the value of FPKM, ranging from green (low expression) to red (high expression).

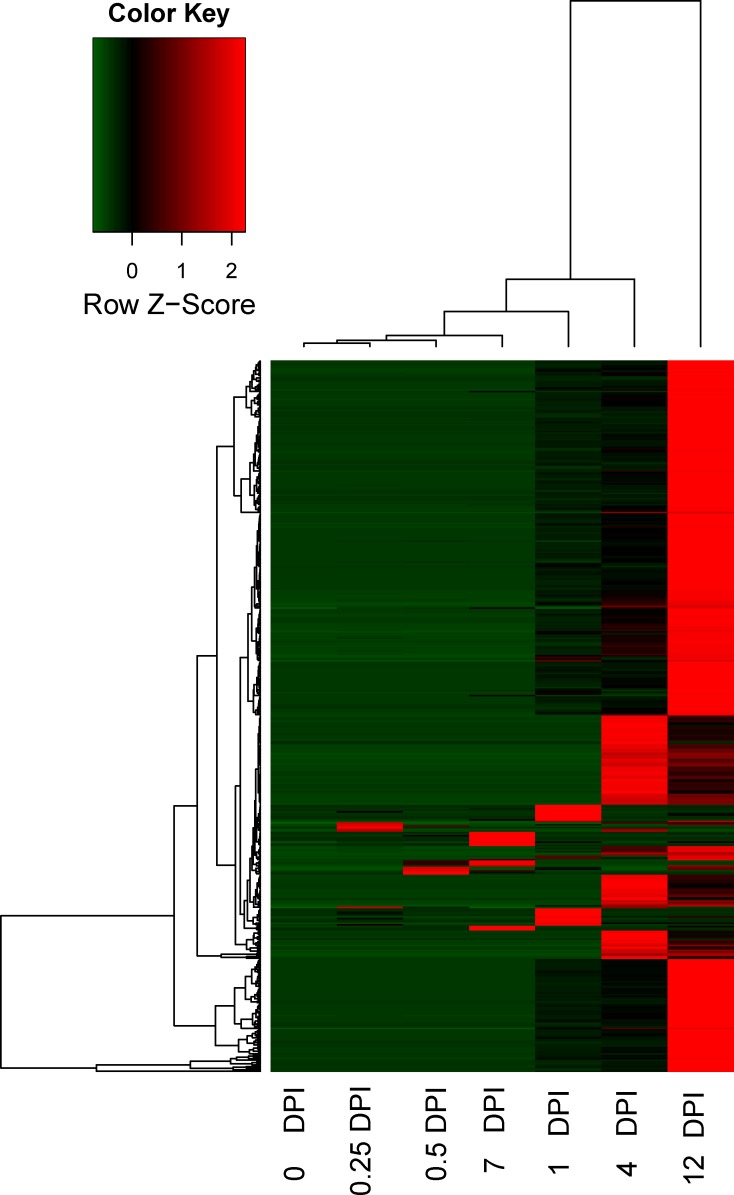

Identification of uniquely expressed unigenes upon C. destructans infection

We indentified uniquely expressed unigenes during early infection by using following cuttoff: (1) the expression of candidate unigenes could not be detected in the uninfected 0 DPI. (2) Among infected library, there was at least one library with RPKM more than 3. By using this cuttoff, we identified 447 unigenes with uniquely expressed. The induced expression of these candidate unigenes has bias at the late time point upon infection (Fig 8). It will be interesting to investigate the candidates in future since uniquely expressed unigenes upon infection were important for systemic resistance.

Fig 8. Heatmap showing the FPKM values of uniquely expressed unigenes upon infection.

The FPKM for the uniquely expressed unigenes upon infection in the control and six infected stages was used for hierarchical analysis. The colors correspond to the value of FPKM, ranging from green (low expression) to red (high expression).

Reactive oxygen species and ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway during C. destructans infection

Plants can produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) that causes oxidative damage during biotic and abiotic stress [30]. The investigation of the ROS can help us to understand the possible function of ROS upon pathogenic infection. In total, we identified 36 ROS-related genes (GO: 0000302 and GO: 0072593), which could response to reactive oxygen species. Among these unigenes, 1 (c61102_g3), 1 (c54370_g1), 2 (c54370_g1, c57939_g2), 7 (c40714_g1, c50821_g1, c52377_g1, c54370_g1, c55185_g1, c55776_g1, c61102_g3) were differentially expressed, which were up-regulated in the libraries of 0.5 DPI, 1 DPI, 4 DPI and 12 DPI, respectively. The qRT-PCR validations for these DEGs could be found at S2 Fig. The RNA-Seq plots were shown at S6 Fig. Among these DEGs, c54370_g1 was up-regulated at three stages (1 DPI, 4 DPI and 12DPI). About 20% ROS-related genes up-regulated at 12 DPI, which suggested that at later stage, most of the ROS-related genes took part in the oxidative damage response upon C. destructans induction.

Ginsenosides are the major pharmacological component of P. ginseng, thus the genes involved in the ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway have been widely identified [31–34]. In total, we identified 248 unigenes involved in ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway, in which CYP450 was the biggest family that included 185 unigenes. There were 20 up-regulated CYP450s and 10 down-regulated CYP450s upon C. destructans infection. The other differentially expressed unigenes involved in ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway included four UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGT), four Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase (AACT) and one squalene/phytoene synthase (SS). Most of the unigenes in the ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway were up-regulated upon C. destructans infection. In total, there were 4 up-regulated UGTs. Among them, c32203_g1 and c56056_g1 were up-regulated at 0.25 DPI and 0.5 DPI, respectively (S2 Fig and S7 Fig). C47595_g2 was up-regulated at both 0.5 DPI and 7 DPI. C57632_g1 was up-regulated at both 0.5 DPI and 12 DPI. At 12 DPI, four AACT (c50541_g1, c54663_g1, c59324_g1, c66211_g1) were up-regulated. Only one SS (c65219_g3) was down-regulated at both 0.5 DPI and 7 DPI. Above results suggested that ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway was affected upon C. destructans induction.

Discussion

De novo transcriptome assembly of the RNA-Seq reads into full transcriptomes and the calculation of the expression level can be conducted for species with unknown genomes [13]. To date, several transcriptomes of P. ginseng focusing on ginsenoside biosynthetic genes have been reported [31–34]. However, global-transcriptome studies of C. destructans infection in P. ginseng remain lacking. The current study investigated C. destructans infection in P. ginseng and used high-throughput RNA-Seq to characterize the transcriptome profile of P. ginseng after C. destructans infection at different time points. The transcriptome upon C. destructans infection extended the transcriptome resources of P. ginseng.

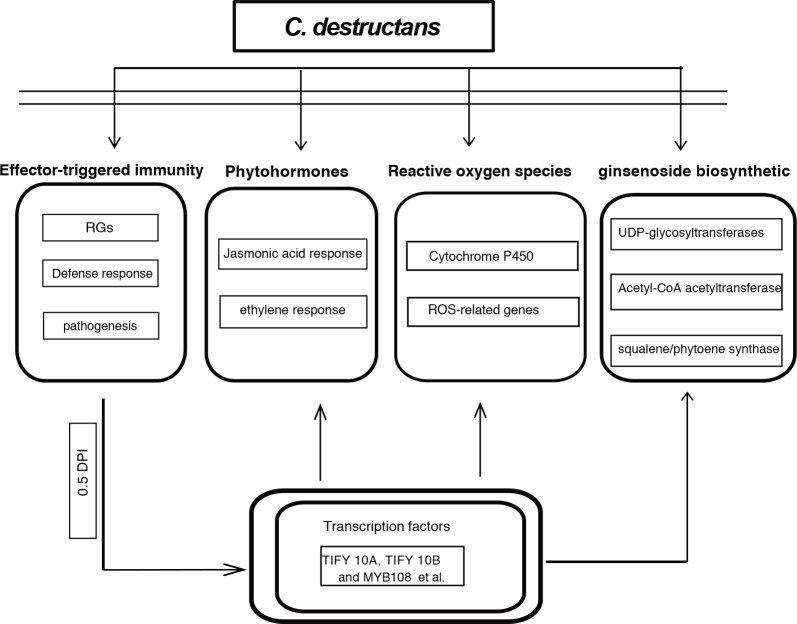

The induced response of P. ginseng to C. destructans infection was characterized to reveal defense-related genes involved in the plant-pathogen interaction. A total of 3,839 and 568 unigenes were up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively. Furthermore, pathogen response unigenes were up-regulated at 0.5 DPI. P. ginseng evolved an innate and inducible resistance or endurance to phytopathogens, pests, extreme environment, and other adverse factors. In the present study, RGs were dramatically induced by C. destructans at 0.5 DPI. Pathogen effector proteins from C. destructans can activate cytoplasmically localized R proteins during disease progression. These RGs might produce effector-triggered immunity (ETI) through gene-for-gene interaction (Fig 9). The DPI of 0.5 might be the essential point for ETI before P. ginseng obtained basal defenses through a phosphorylation cascade. After the immunity signal passed into nucleus, many defense related TFs (TIFY 10A, TIFY 10B and MYB108 et al) were activated. These transcript factors might further affected phytohormones, reactive oxygen species and ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway (Fig 9). C. destructans induction had effect on phytohormones, such as jasmonic acide and ethylene response. At the same time ROS-related genes might protect P. ginseng against invasion of C. destructans (Fig 9). Moreover, unigenes involved in ginsenoside biosynthetic might also play important roles in the response to C. destructans infection.

Fig 9. Model of C. destructans infection in the effector-triggered immunity, phytohormones, reactive oxygen species and ginsenoside biosynthetic pathway.

This study is the first to report on defense-related DEGs that potentially improve the resistance of P. ginseng against C. destructans-caused root rot disease. The results of this study deepen our understanding of pathogen–plant interactions. Furthermore, these candidate pathogen-response unigenes may be used to increase the resistance or tolerance of P. ginseng to root rot disease via transformation strategy. Most importantly, these canditated C. destructans response genes at 0.5 DPI were identified as essential genes for ETI, which could be used as markers for the early detection of C. destructans infection.

Supporting Information

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

Fold changes of the transcript levels at different time points are shown. The average expression level at 0 DPI was set to 1. Error bars represent standard error from three independent experimental replicates.

(TIF)

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

Unigenes with FPKM = 0 in uninfected library are not shown in this figure.

(TIF)

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

(DOC)

(XLS)

(XLS)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files and available from the Short Read Archive database under Accession Number SRR1639601.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (81072992 and 81373911), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Scientific Research Institutes for Public Welfare (yz-12-17), and the PUMC Youth Fund (3332013113). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Vogler BK, Pittler MH, Ernst E. The efficacy of ginseng. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1999;55(8):567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Hara M, Kiefer D, Farrell K, Kemper K. A review of 12 commonly used medicinal herbs. Archives of Family Medicine. 1998;7(6):523–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman M, Punja ZK. Factors influencing development of root rot on ginseng caused by Cylindrocarpon destructans. Phytopathology. 2005;95(12):1381–1390. 10.1094/PHYTO-95-1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang CS, Lim JH, Seo MW, Song JY, Kim HG. Direct detection of Cylindrocarpon destructans, root rot pathogen of ginseng by nested PCR from soil samples. Mycobiology. 2010;38(1):33–38. 10.4489/MYCO.2010.38.1.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang X, Phillips D, Li H, Sivasithamparam K, Barbetti MJ. Comparisons of virulence of pathogens associated with crown and root diseases of strawberry in Western Australia with special reference to the effect of temperature. Scientia Horticulturae. 2011;131:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang X, Phillips D, Li H, Sivasithamparam K, Barbetti M. Severity of crown and root diseases of strawberry and associated fungal and oomycete pathogens in Western Australia. Australasian Plant Pathology. 2011;40(2):109–119. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rego C, Oliveira H, Nascimento T. Characterisation of Cylindrocarpon destructans Isolates from Grapevines in Portugal. Phytopathologia Mediterranea. 2001;40(3):343–350. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rego C, Farropas L, Nascimento T, Cabral A, Oliveira H. Black foot of grapevine: sensitivity of Cylindrocarpon destructans to fungicides. Phytopathologia Mediterranea. 2006;45(4):93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song JY, Seo MW, Kim SI, Nam MH, Lim HS, Kim HG. Genetic diversity and pathogenicity of Cylindrocarpon destructans isolates obtained from Korean Panax ginseng. Mycobiology. 2014;42(2):174–180. 10.5941/MYCO.2014.42.2.174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman M, Punja ZK. Influence of iron on Cylindrocarpon root rot development on ginseng. Phytopathology. 2006;96(11):1179–1187. 10.1094/PHYTO-96-1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taffouo VD, Ngwene B, Akoa A, Franken P. Influence of phosphorus application and arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation on growth, foliar nitrogen mobilization, and phosphorus partitioning in cowpea plants. Mycorrhiza. 2014;24(5):361–368. 10.1007/s00572-013-0544-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29(7):644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(16):3448–3449. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marioni JC, Mason CE, Mane SM, Stephens M, Gilad Y. RNA-seq: an assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Research. 2008;18(9):1509–1517. 10.1101/gr.079558.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Feng Z, Wang X, Zhang X. DEGseq: an R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):136–138. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ernst J, Bar-Joseph Z. STEM: a tool for the analysis of short time series gene expression data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:191 10.1186/1471-2105-7-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J- J, Ekramoddoullah AK. The family 10 of plant pathogenesis-related proteins: their structure, regulation, and function in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 2006;68(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koning AJ, Rose R, Comai L. Developmental expression of tomato heat-shock cognate protein 80. Plant Physiology. 1992;100(2):801–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devoto A, Ellis C, Magusin A, Chang HS, Chilcott C, Zhu T, et al. Expression profiling reveals COI1 to be a key regulator of genes involved in wound- and methyl jasmonate-induced secondary metabolism, defence, and hormone interactions. Plant Molecular Biology. 2005;58(4):497–513. 10.1007/s11103-005-7306-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bassanezi RB, Amorim L, Bergaminfilho A, Berger RD. Gas exchange and emission of chlorophyll fluorescence during the monocycle of rust, angular leaf spot and anthracnose on bean leaves as a function of their trophic characteristics. Journal of Phytopathology. 2002;150:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mouekouba LD, Zhang L, Guan X, Chen X, Chen H, Zhang J, et al. Analysis of Clonostachys rosea-induced resistance to tomato gray mold disease in tomato leaves. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102690 10.1371/journal.pone.0102690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro LR, Salvaudon L, Mauck KE, Pulido H, De Moraes CM, Stephenson AG, et al. Disease interactions in a shared host plant: effects of pre-existing viral infection on cucurbit plant defense responses and resistance to bacterial wilt disease. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77393 10.1371/journal.pone.0077393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurth F, Mailander S, Bonn M, Feldhahn L, Herrmann S, Grosse I, et al. Streptomyces-induced resistance against oak powdery mildew involves host plant responses in defense, photosynthesis, and secondary metabolism pathways. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2014;27(9):891–900. 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0296-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanholme B, Grunewald W, Bateman A, Kohchi T, Gheysen G. The tify family previously known as ZIM. Trends in Plant Science. 2007;12(6):239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauwels L, Goossens A. Fine-tuning of early events in the jasmonate response. Plant Signaling and Behavior. 2008;3(10):846–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aparicio-Fabre R, Guillén G, Loredo M, Arellano J, Valdés-López O, Ramírez M, et al. Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) PvTIFY orchestrates global changes in transcript profile response to jasmonate and phosphorus deficiency. BMC Plant Biology. 2013;13(1):26 10.1186/1471-2229-13-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sathiyaraj G, Srinivasan S, Subramanium S, Kim YJ, Kwon WS, Yang DC. Polygalacturonase inhibiting protein: isolation, developmental regulation and pathogen related expression in Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. Molecular Biology Reports. 2010;37(7):3445–3454. 10.1007/s11033-009-9936-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apel K, Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2004;55:373–399. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li C, Zhu Y, Guo X, Sun C, Luo H, Song J, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals ginsenosides biosynthetic genes, microRNAs and simple sequence repeats in Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:245 10.1186/1471-2164-14-245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo H, Sun C, Sun Y, Wu Q, Li Y, Song J, et al. Analysis of the transcriptome of Panax notoginseng root uncovers putative triterpene saponin-biosynthetic genes and genetic markers. BMC Genomics. 2011;12 Suppl 5:S5 10.1186/1471-2164-12-S5-S5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathiyalagan R, Subramaniyam S, Natarajan S, Kim YJ, Sun MS, Kim SY, et al. Insilico profiling of microRNAs in Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer). Journal of Ginseng Research. 2013;37(2):227–247. 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun C, Li Y, Wu Q, Luo H, Sun Y, Song J, et al. De novo sequencing and analysis of the American ginseng root transcriptome using a GS FLX Titanium platform to discover putative genes involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:262 10.1186/1471-2164-11-262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

Fold changes of the transcript levels at different time points are shown. The average expression level at 0 DPI was set to 1. Error bars represent standard error from three independent experimental replicates.

(TIF)

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

Unigenes with FPKM = 0 in uninfected library are not shown in this figure.

(TIF)

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

The y-axes represent normalized FPKM and the x-axes represent different stages after C. destructans infection.

(TIF)

(DOC)

(XLS)

(XLS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files and available from the Short Read Archive database under Accession Number SRR1639601.