Abstract

The incidence of common carotid artery occlusion (CCAO) is approximately 3% in patients who undergo angiography for symptomatic cerebrovascular disease; however, few studies have reported on management of this condition. The objective of this article was to analyze risk factors, therapeutic options, and clinical benefits of surgical treatment at a hospital in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Data were collected from medical records of 40 patients with CCAO who were treated from June 2002 to October 2013. Results were analyzed retrospectively. Most of the patients were men (63.0%), who were significantly younger than women. Most of the participants had hypertension (90.0%), and more than half had a history of smoking (52.5%). The mean number of coexisting comorbidities/risk factors was 2.9 ± 1.0. Half of our sample had ipsilateral patent internal and external carotid artery, and 32.5% presented with an occluded internal carotid artery and a patent external artery. Patients with both an internal and an external occluded carotid artery (12.5%) were significantly older. Contralateral arteriosclerosis was observed in 65% of the patients, mainly represented by 50 to 90% stenosis. Most patients were symptomatic (67.5%), and hemiparesis was the most common symptom (55.0%) found. Most (77.5%) of the patients underwent the medical treatment; one out of three endovascular approaches failed. During the mean follow-up of 55 ± 43 months (range, 2–136 months), 17.5% of the patients died within 4 days after surgical repair and after along 123 months of clinical follow-up. Coexisting comorbidities/risk factors were significantly associated with fatal outcomes, such as acute myocardial infarction. This study provides scientific evidences on treatment and outcomes of CCAO.

Keywords: carotid revascularization, common carotid artery occlusion, Rile classification, chronic stage, open surgery

Common carotid artery occlusion (CCAO) has been little discussed in the literature compared with occlusion of the internal carotid artery (ICA). However, CCAO seems to be a different disease because of its presentation, treatment, and incidence.

CCAO is diagnosed in approximately 3% of the symptomatic patients undergoing carotid angiography1 and in only 1 to 5% of the patients with symptomatic cerebrovascular disease.2 3 The development of exuberant collateral circulation and patency of the carotid bifurcation seems to protect against ischemic brain lesions.3 However, several symptoms can occur, including hemispheric stroke, amaurosis fugax, and brain hypoperfusion.2

To date, no consensus exists for treatment of asymptomatic patients, and decisions for treatment of symptomatic patients are controversial and made according to each case.4 The 2011 American Heart Association guidelines recommend open surgery or endovascular intervention to treat symptomatic ischemic lesions affecting the anterior cerebral circulation caused by CCAO.5 In contrast, the 2009 European Society of Cardiology Protocol has no specific recommendations on this matter,6 which emphasizes the need for further studies.

We studied symptoms, treatment options, and clinical evolution of 40 patients with CCAO in our ambulatory service for carotid disease. This study was intended to provide more data and promote discussion about this disease.

Methods

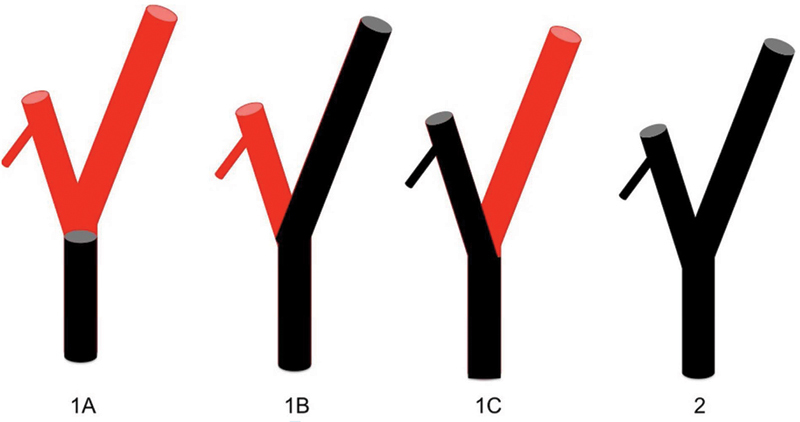

This study was conducted from June 2002 to October 2013 and included 40 patients diagnosed with CCAO and treated at a referral tertiary center, the hospital of the medical school of the São Paulo University in Brazil. Data collected from patients' medical records were gender, age, presence of comorbidities/risk factors, level of lesion severity based on the Rile classification (Fig. 1),7 diagnostic procedures, and presence of contralateral arteriosclerosis, ipsilateral and contralateral symptoms, treatment type, and clinical outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Rile classification of common carotid artery occlusion.

CCAO diagnosis was confirmed by image investigation in symptomatic patients, and was a finding during diagnostic investigation of other conditions or during screening patients with atherosclerosis in other sites in asymptomatic patients.

We entered data into a standard form that was completed for all patients with carotid disease. Descriptive analysis was done by using Microsoft Excel (2010, Humacao, PR). After testing of ranges, an unpaired Student t-test was used to compare means and standard deviations. Frequencies were analyzed by using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Survival rates regarding associated comorbidities/risk factors, presence of symptoms, and type of treatment were calculated with the use of Kaplan–Meier method. Log-rank test was used to compare survival distributions. Significant differences were established with p < 0.05.

Results

Patient demographic characteristics and comorbidities are described in Table 1. Women (37.0%) were significantly older than men (63.0%). We found an isolated comorbidity up to six comorbidities/risk factors associated, but without significant differences between genders concerning the mean number of risk factors. Most patients had hypertension, and more than half of the patients were smokers (52.5%). No significant differences for any comorbidity were found between men and women.

Table 1. Patient demographics, comorbidities/risk factors, and data on lesions in 40 CCAO patients.

| Parameters | Male (n = 25) |

Female (n = 15) |

Total (n = 40) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 63.8 (7.6) | 70.4 (6.9) | 66.3 (4.7) | 0.010 |

| age range (y) | 53–75 | 60–82 | 53–82 | |

| Mean number of comorbidities (SD) | 1.8 (1.2) | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.9 (1.0) | 0.232 |

| Comorbidities (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 88.0 | 93.3 | 90.0 | 1.000 |

| Smoking | 56.0 | 46.7 | 52.5 | 0.368 |

| Diabetes | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 0.740 |

| Dyslipidemia | 28.0 | 33.3 | 30.0 | 1.000 |

| PVD | 28.0 | 6.7 | 20.0 | 0.061 |

| Coronary artery disease | 28.0 | 6.7 | 20.0 | 0.061 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 12.0 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 0.628 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.0 | 13.3 | 5.0 | 0.261 |

| Side of the lesion (%) | ||||

| Left | 56.0 | 60.0 | 57.5 | |

| Right | 44.0 | 33.3 | 40.0 | |

| Bilateral | 0.0 | 6.7 | 2.5 | 0.404 |

| Rile classes (%) | ||||

| 1A | 48.0 | 53.3 | 50.0 | |

| 1B | 36.0 | 26.7 | 32.5 | |

| 1C | 8.0 | 0.0 | 2.5 | |

| 2 | 8.0 | 20.0 | 12.5 | 0.564 |

Abbreviations: CCAO, common carotid artery occlusion; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; SD, standard deviation.

We observed equal numbers of right- and left-sided lesions in both the genders. Half of the sample had 1A lesions based on the Rile classification. Women tended to have more class 2 lesions based on the Rile classification. The mean age of patients in Rile class 2 (71.8 ± 3.9 years) was significantly higher (p = 0.030) than that of patients in classes 1A (66.0 ± 9.2 years) and 1B (64.8 ± 6.5 years).

Arteriography was used from 2005 to 2007, computed tomography angiography between 2008 and 2011, and Doppler ultrasonography from the middle of 2012 to 2013 in 100% of the cases.

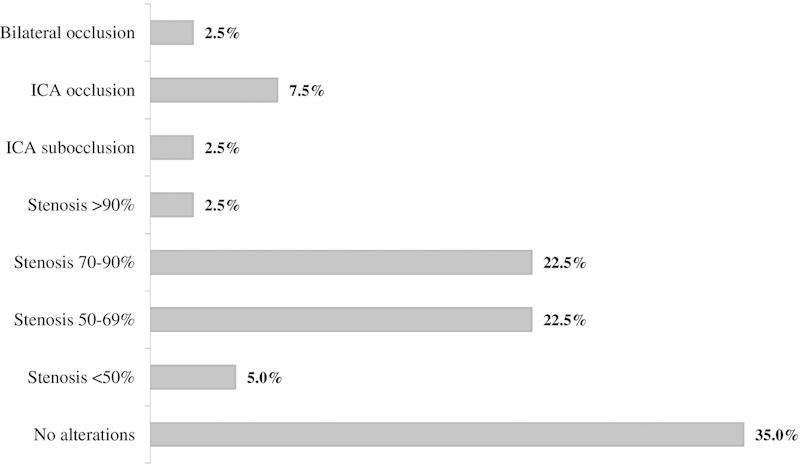

Contralateral arteriosclerosis was found in 65.0% of the patients (Fig. 2). Presence of contralateral arteriosclerosis showed nonsignificant negative correlations with age (r = −0.17) and number of comorbidities/risk factors (r = −0.21).

Fig. 2.

Contralateral atherosclerosis observed in 40 CCAO patients. CCAO, common carotid artery occlusion.

No ipsilateral symptoms were observed in 50% of the patients overall (55.0% of men and 45.0% of women). Among patients with ipsilateral symptoms (70.0% of men and 30.0% of women; p = 0.512), hemiparesis was the most frequent (55.0%), followed by syncope and dizziness (10.0%), hemiplegia (15.0%), amaurosis (10.0%), aphasia (5.0%), and mental confusion after three strokes (5.0%). Contralateral symptoms, in turn, occurred in 17.5% of the patients, including vertebrobasilar symptoms (5.0%), amaurosis (5.0%), syncope (2.5%), transient ischemic attack (TIA, 2.5%), and mental confusion (2.5%). Patients with contralateral symptoms (mean age, 67.6 ± 7.8 years) were significantly (p = 0.019) older than those without such symptoms (60.0 ± 5.7 years).

Patients were predominantly treated with a medical approach (77.5%). One of these patients declined to undergo the recommended surgical procedure. Eight symptomatic patients (20.0%) had conventional surgical intervention (including conventional endarterectomy [four patients], subclavian–carotid grafts [three patients], and aortic–carotid graft [1 patient]). One of the surgical cases involved bilateral treatment. Neurological symptoms remained stable after surgical treatment. In one patient, an endovascular approach was not successful.

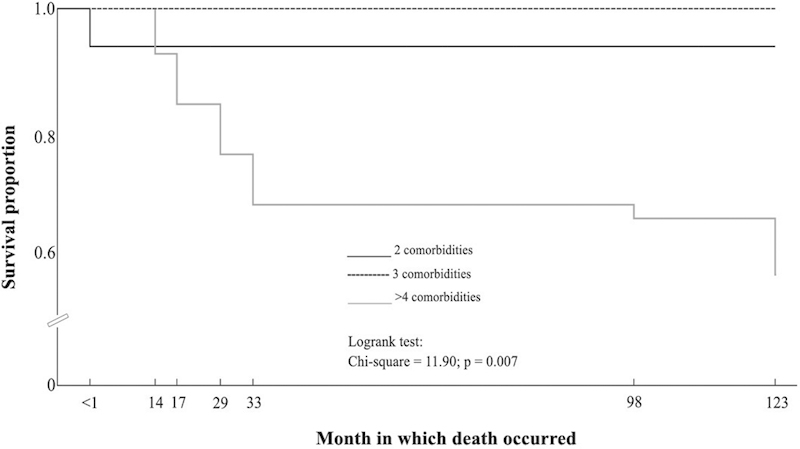

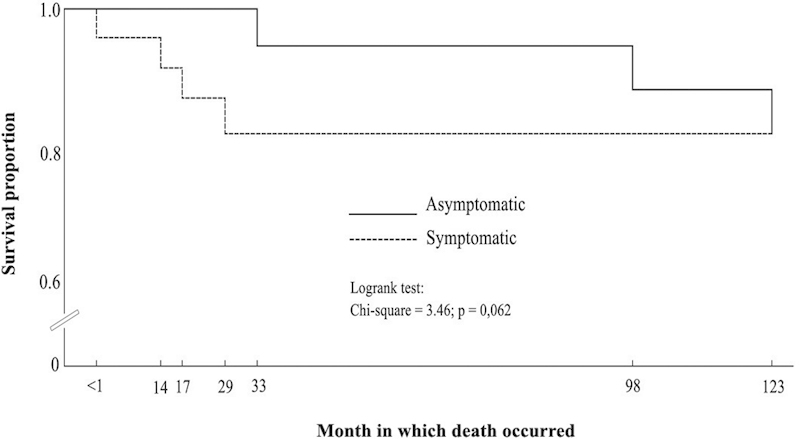

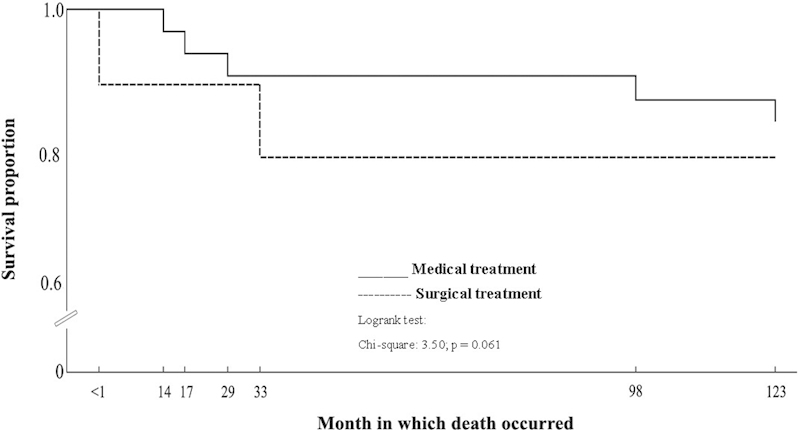

Mean duration of follow-up was 55 ± 43 months (range, 2–136 months). During follow-up, 17.5% of the patients died of different causes: one patient (2.5%) died after hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident at 4 days after surgery; 7.5% died of acute myocardial infarction (at 23, 98, and 123 months of follow-up). Congestive cardiac insufficiency (2.5%) was the cause of a death at 14 months; ischemic cerebrovascular accident (2.5%), at 17 months; and advanced neoplasia (2.5%), at 29 months. The mean age of patients who died (67.4 ± 9.0 years) was not statistically different (p = 0.678) from that of patients who were alive at the end of data collection (66.0 ± 7.9 years). Patients who died had significantly more comorbidities than those who were alive (3.7 ± 0.8 and 2.8 ± 1.0, respectively; p = 0,026), and this finding was confirmed by log-rank test (p = 0.007), as demonstrated in Fig. 3. Symptoms (Fig. 4) and type of treatment (Fig. 5) did not influence patients' risk of death.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing survival proportions according to the number of coexisting comorbidities/risk factors.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing survival proportions for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients.

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves comparing survival proportions according to the type of treatment.

Discussion

CCAO is a relatively rare condition, and both its natural history7 and recommendations for treatment are still unclear.5 6 Few clinical studies have addressed CCAO, and the number of patients studied so far has been insufficient to establish any recommendations. Among the 21 published studies on CCAO treatment, 11 were case reports involving a total of 16 patients.8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 The other 10 studies2 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 involved 6 to 24 patients, with a total of 130 patients.

Klonaris et al7 recently reported that the prevalence of CCAO is higher in men (73%) than in women, a finding similar to our results. The mean patient age in our study is very close to that in the literature (66.3 ± 4.7 [range 41–76 years] and 65 ± 6.9 years [range 53–82 years], respectively). We found out that women were significantly older than men, which constitutes a finding that deserves to be added to the current knowledge on CCAO. Almost all patients in our series were hypertensive, and more than half had a history of smoking. The association of such risk factors and extracranial carotid disease is well established.5 Our patients had a mean number of 2.9 ± 1.0 associated comorbidities/risk factors, primarily hypertension and smoking.

The majority (94.5%) of the patients reported in the literature7 were symptomatic at presentation; TIAs accounted for 57.8% of the cases. In our study, 67.5% of the patients had ipsilateral plus contralateral symptoms; only 2.5% presented with a TIA. Most studies (n = 11) were published before 2000, and diagnosis of CCAO has probably changed in the last decade. This can at least in part explain such discrepancies. In addition, studies have focused on surgical treatment of CCAO, which is recommended for symptomatic disease.

Some studies have reported a marked prevalence of left over right CCAO. This finding can be explained by hemodynamic differences between the two common carotid arteries, differences in arterial length, and direct encroachment of aortic plaque into the CCA origin on the left.2 3 Although we observed left CCAO in 57.5% of the patients and right CCAO in 40.0%, we could not corroborate such prevalent involvement of the left common carotid artery because no significant difference was found. In a study on the incidence of anterograde ICA collateral flow in 10 patients with CCAO,3 the right side was occluded in 60%.

Regarding the Rile classification, we found a slightly lower percentage of patients in class 1A (50.0%) and a slightly higher percentage of those in class 1B (32.5%) compared with the literature (61.5 and 26.6%, respectively). This means that most patients with CCAO have patency in both the ipsilateral ICA and external carotid artery (ECA), while about one-third might present with an occluded ICA. Class 1C (an occluded ECA and a patent ICA) occurs far less frequently in both the literature (0%) and in our experience (2.5%). Finally, occlusion of both ipsilateral ICA and ECA has been observed in very similar percentages of approximately 12.0%. Patients of our series with Rile class 2 were significantly older than those with classes 1A and 1B, and female patients tended to have ipsilateral ICA and ECA occluded more frequently than did men. It makes some sense in our experience, as female patients were significantly older than male patients.

Medical treatment was the choice for 77.5% of our patients, as half of them were asymptomatic. Only eight patients underwent traditional revascularization procedures, and an endovascular approach failed in one case. As all available studies concern surgical treatment of CCAO, it is hard to establish a reliable comparison. Among the 146 patients described in the literature, only 2 underwent an endovascular procedure, showing that such approach has not yet been well established for the treatment of CCAO.7 In fact, technical difficulties to cross-occlusive lesions and the procedural risks observed with endovascular repair of a few cases of chronic ICA26 allow exclusion of such approach in cases of CCAO, at least for now.

The mean duration of follow-up of this series was longer than that reported in a literature review7 (55 ± 43 months and 25.6 ± 11.2 months, respectively), although ranges were quite similar (2–136 months and 2–110 months, respectively). The literature reports only one fatal ipsilateral stroke 4 days after the surgical procedure. In our experience, 17.5% of the patients died between 4 days after surgery and 123 months of follow-up. Congestive cardiac insufficiency was the cause of one death in our series 4 days after traditional intervention as well. Acute myocardial infarction was the main cause of death (7.5%) at 23, 98, and 123 months of follow-up. Patients' age, symptoms, and type of treatment (medical or surgical) were not associated with the fatal outcomes. However, patients who died during follow-up had significantly more comorbidities/risk factors than did those alive at study end.

The clinical outcomes of asymptomatic patients is still unclear, and the traditional interventions recommended for symptomatic patients still bring questionable benefits for asymptomatic patients; although such interventions prevent neurologic events and improve cerebrovascular insufficiency, they are also associated with important rates of complications (6.6–11.1%).

Our study has limitations. This was a retrospective analysis, and the sample is from a tertiary center. It is likely that many patients remain asymptomatic without investigation.

Conclusion

CCAO is a condition strongly related to hypertensive and smoking in male patients. It affects female patients at a more advanced age. The worsening of the occlusion seems to be highly associated with advanced age. Only 50% of the cases are symptomatic, and the main ipsilateral symptom is the hemiparesis, with high frequency of contralateral arteriosclerosis at image examinations but lower frequency of contralateral symptoms. Patient outcomes are not influenced by age, gender, clinical symptoms, or type of treatment, but by the number of associated coexisting comorbidities/risk factors.

Scientific evidence on treatment and evolution of CCAO is still lacking, and extensive multicentric studies would be helpful in providing subsidies for the development of a procedural protocol for such cases.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Funding None of the authors has any conflict of interest or funding.

References

- 1.Hass W K, Fields W S, North R R, Kircheff I I, Chase N E, Bauer R B. Joint study of extracranial arterial occlusion. II. Arteriography, techniques, sites, and complications. JAMA. 1968;203(11):961–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belkin M Mackey W C Pessin M S Caplan L R O'Donnell T F Common carotid artery occlusion with patent internal and external carotid arteries: diagnosis and surgical management J Vasc Surg 19931761019–1027., discussion 1027–1028 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura A, Wakugawa Y, Yasaka M. et al. Antegrade internal carotid artery collateral flow and cerebral blood flow in patients with common carotid artery occlusion. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(10):1561–1566. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.10.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takagi T, Yoshimura S, Yamada K, Enomoto Y, Iwama T. Angioplasty and stenting of totally occluded common carotid artery at the chronic stage. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010;50(11):998–1000. doi: 10.2176/nmc.50.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brott T G, Halperin J L, Abbara S. et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81(1):E76–E123. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liapis C D Bell P R Mikhailidis D et al. ESVS guidelines. Invasive treatment for carotid stenosis: indications, techniques Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 200937(4, Suppl):1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klonaris C, Kouvelos G N, Kafeza M, Koutsoumpelis A, Katsargyris A, Tsigris C. Common carotid artery occlusion treatment: revealing a gap in the current guidelines. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagasawa S Tanaka H Kawanishi M Ohta T Contralateral external carotid-to-external carotid artery (half-collar) saphenous vein graft for common carotid artery occlusion Surg Neurol 1996452138–141., discussion 141–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi T, Houkin K, Ito F, Kohama Y. Transverse cervical artery bypass pedicle for treatment of common carotid artery occlusion: new adjunct for revascularization of the internal carotid artery domain. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(2):299–302. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199908000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melgar M A, Weinand M E. Thyrocervical trunk-external carotid artery bypass for positional cerebral ischemia due to common carotid artery occlusion. Report of three cases. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14(3):e7. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.14.3.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabb C H, Moneta G L. Staged cerebral revascularization in a patient with an occluded common carotid artery. Stroke. 2005;36(8):E68–E70. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000174191.19216.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crome O, Kermer P, Buhk J H, Schoendube F, Kastrup A. Emergency surgical revascularization in a patient with acute symptomatic common carotid artery occlusion. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24(1):152–154. doi: 10.1159/000103622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pintér L, Cagiannos C, Bakoyiannis C N, Kolvenbach R. Hybrid treatment of common carotid artery occlusion with ring-stripper endarterectomy plus stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46(1):135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schubert G A Rewerk S Riester T Huck K Vajkoczy P Treatment of hemodynamic insufficiency in chronic CCA occlusion using a short saphenous vein interposition graft: diagnostic and technical considerations. An illustrative case report Neurosurg Rev 2008311123–126., discussion 126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue T Tsutsumi K Adachi S Tanaka S Kunii N Indo M Direct and primary carotid endarterectomy for common carotid artery occlusion. Report of 2 cases Surg Neurol 2008696620–626., discussion 626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider U C von Weitzel-Mudersbach P Hoffmann K T Vajkoczy P Extracranial posterior communicating artery bypass for revascularization of patients with common carotid artery occlusion Neurosurgery 20106761783–1789., discussion 1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirazi M H, Tennant, Insall R Novel carotid surgery in an asymptomatic totally occluded common carotid artery J Pak Med Assoc 2011612187–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collice M, D'Angelo V, Arena O. Surgical treatment of common carotid artery occlusion. Neurosurgery. 1983;12(5):515–524. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riles T S, Imparato A M, Posner M P, Eikelboom B C. Common carotid occlusion. Assessment of the distal vessels. Ann Surg. 1984;199(3):363–366. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198403000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGuiness C L, Short D H, Kerstein M D. Subclavian-external carotid bypass for symptomatic severe cerebral ischemia from common and internal carotid artery occlusion. Am J Surg. 1988;155(4):546–550. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fry W R Martin J D Clagett G P Fry W J Extrathoracic carotid reconstruction: the subclavian-carotid artery bypass J Vasc Surg 199215183–88., discussion 88–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin R S III, Edwards W H, Mulherin J L Jr, Edwards W H Jr. Surgical treatment of common carotid artery occlusion. Am J Surg. 1993;165(3):302–306. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80830-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan T M. Subclavian-carotid bypass to an “isolated” carotid bifurcation: a retrospective analysis. Ann Vasc Surg. 1996;10(3):283–289. doi: 10.1007/BF02001894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Archie J P Jr. Axillary-to-carotid artery bypass grafting for symptomatic severe common carotid artery occlusive disease. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(6):1106–1112. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linni K, Aspalter M, Ugurluoglu A, Hölzenbein T. Proximal common carotid artery lesions: endovascular and open repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(6):728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hauck E F Ogilvy C S Siddiqui A H Hopkins L N Levy E I Direct endovascular recanalization of chronic carotid occlusion: should we do it? Case report Neurosurgery 2010674E1152–E1159., discussion E1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]