SUMMARY

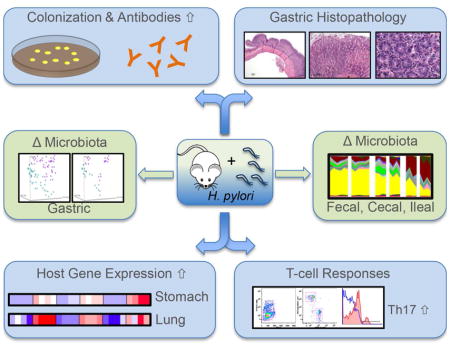

Helicobacter pylori is a late-in-life human pathogen with potential early-life benefits. Although H. pylori is disappearing from the human population, little is known about the influence of H. pylori on the host’s microbiota and immunity. Studying the interactions of H. pylori with murine hosts over six months, we found stable colonization accompanied by gastric histologic and antibody responses. Analysis of gastric and pulmonary tissues revealed increased expression of multiple immune response genes, conserved across mice and over time in the stomach, and more transiently in the lungs. Moreover, H. pylori infection led to significantly different population structures in both the gastric and intestinal microbiota. These studies indicate that H. pylori influences the microbiota and host immune responses not only locally in the stomach, but distantly as well, affecting important target organs.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Starting at birth, humans are extensively exposed to a wide variety of microbial cells, which colonize the inner and outer surfaces of our body and subsequently shape our immune system and physiology (Dominguez-Bello et al., 2010; Hooper et al., 2012). The gastro-intestinal tract is one of the most densely populated sites in the human body and accordingly plays a major role in the development of the immune system (Goodnow et al., 2005; Kabat et al., 2014). Later in life, disruption of this microbial community may lead to disease consequences (Buffie et al., 2015; Hogenauer et al., 2006); conversely, restoration of impacted microbial community could be an efficient approach for their reduction (Reid et al., 2011; van Nood et al., 2013).

Despite its acidic environment, the human stomach is home to a diverse microbial community (Bik et al., 2006; Maldonado-Contreras et al., 2011). Depending on the gastric milieu, the composition and functions of the microbial community can vary (Manson et al., 2008; Martinsen et al., 2005). A prominent member of the gastric microbiota is Helicobacter pylori; in colonized humans, its relative abundance usually is high, but can vary (Bik et al., 2006). H. pylori is typically acquired early in life (Goodman et al., 1996; Kumagai et al., 1998), often transmitted from mothers (Perez-Perez et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 1999), and persistently colonizes the gastric mucosa (Oertli et al., 2013). Unless antibiotic therapy is used, colonization generally persists for decades, or throughout the entire host lifespan (Kosunen et al., 1997). H. pylori carriage is associated with illnesses, such as peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (Ernst and Gold, 2000). For decades, H. pylori research has focused on understanding the pathogenesis of these diseases (Amieva et al., 2003; Mahdavi et al., 2002; Odenbreit et al., 2000; Robinson et al., 2008).

H. pylori prevalence in populations in developed countries is diminishing due to changing hygienic standards and antibiotic treatments. Despite the significance of H. pylori as a pathogen, concerns have been raised about the consequences of the loss of an organism that has colonized humans for >100,000 years (Moodley et al., 2012). Observations of inverse associations of H. pylori with diseases include early onset-asthma (Arnold et al., 2011a; Chen and Blaser, 2007, 2008), gastrointestinal (Cohen et al., 2012; Higgins et al., 2011; Rothenbacher et al., 2000) and systemic (Perry et al., 2010) infections, and Barrett’s esophagus and its consequences (Corley et al., 2008; Rubenstein et al., 2014; Thrift et al., 2012). In mice, the age at which H. pylori is acquired is critical in influencing outcomes; challenged adult mice developed pre-neoplastic lesions, but neonatal mice were protected against severe pathology by immune tolerance (Arnold et al., 2011b). The fact that this tolerance subsequently protected against the development of asthma (Arnold et al., 2011a) highlights the importance of cross-talk between particular bacterial colonizers and the host’s immune system. During the first years of life, the development and maturation of the mammalian immune system is strongly dependent on the microorganisms to which it is exposed, and simultaneously, the immune system shapes the composition of our residential bacterial community (Hooper and Macpherson, 2010); the two phenomena are cross-linked.

Studies to explore the potential effects of H. pylori using the C57BL/6 mouse model and the functional CagA H. pylori strain PMSS1, highlight the importance of the developmental stage of the mouse at time of infection (Arnold et al., 2011a; Arnold et al., 2011b; Oertli and Muller, 2012; Oertli et al., 2013; Oertli et al., 2012). However, the most relevant time windows are not yet known, nor are the direct or indirect influences of H. pylori on gastric and gut microbial communities and immunity. The goal of the current study was to understand the effect of gastric H. pylori colonization on local and systemic immune responses and whether it affects the composition of the gastro-intestinal microbiota.

RESULTS

C57Bl/6 mice were stably colonized with H. pylori PMSS1

We first examined whether experimental challenge with H. pylori strain PMSS1 would lead to productive infection resulting in stable colonization in Cohort 1 (infected at 4-weeks of age) and Cohort 2 (age 6-weeks) mice (Figure S1). Culture and PCR analyses of the two cohorts detected H. pylori infection in 44 of 46 challenged mice, but in none of 40 non-challenged control mice, as expected. During the first month following challenge, the levels of colonization varied extensively (range 102 to 108 colony forming units (CFU) per gram stomach), but then stabilized (Figure 1A). In most challenged mice, H. pylori were detected by culture and confirmed by PCR or by PCR alone (Figure 1A, Figure S1). The only two mice that were both culture- and PCR-negative had antibody responses to H. pylori, and high gastric histologic inflammatory scores, with characteristic organisms visualized. Taken together, all 48 H. pylori-challenged mice were successfully infected, and control mice were all culture- and PCR-negative (Figure S1). Over the 6-month study period, all mice regardless of age at challenge were stably H. pylori-infected (median colonization 105–106 CFU/g of stomach (Figure 1A), corresponding to ~105 CFU per mouse stomach.

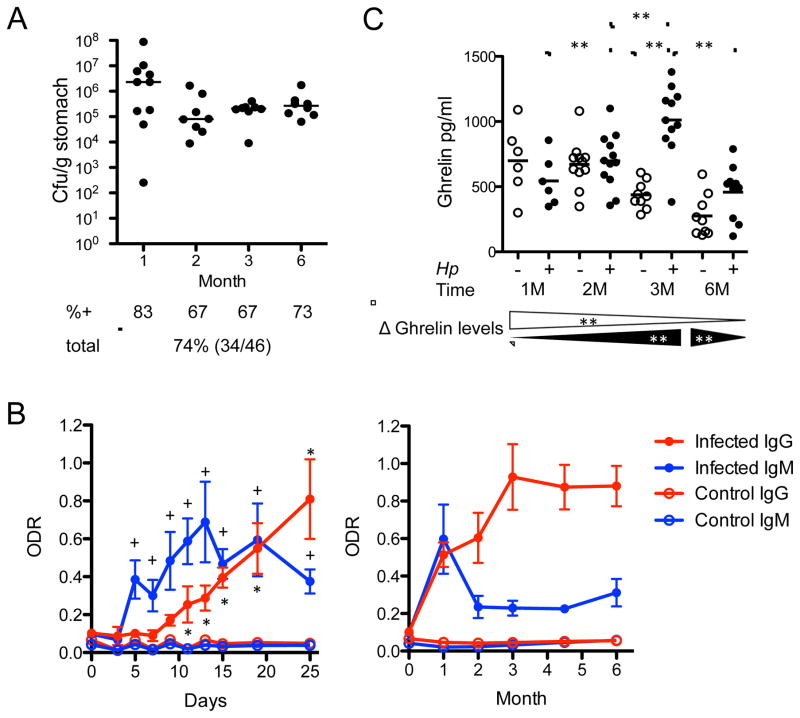

Figure 1. Bacterial colonization, and host antibody and ghrelin responses of C57Bl/6 mice infected with H. pylori strain PMSS1.

(A) Colony-forming units (Cfu) per gram stomach in animals sacrificed at the indicated times post-infection. Bars indicate the medians; %+ indicates percent of mice positive for H. pylori, as determined by culture for each time point of sacrifice; total percentage and number of (positive/total number) of mice is shown in bottom line; (B) Antibody responses. Early (first 25 days following challenge) and long term (over 6 months) anti-H. pylori IgM and IgG responses of control and infected mice expressed in optical density ratios (ODR). (+) or (*) indicates when IgM or IgG levels, respectively, were significantly higher compared to baseline; Mann-Whitney U-Test, +,*p<0.05; (C) Ghrelin responses. Levels of total plasma ghrelin measured over the 6-month challenge (horizontal bars represent mean values). Bottom strip: Δ Ghrelin, changes of ghrelin over time for controls (open triangles) and infected mice (black triangles); Kruskal-Wallace followed by Mann-Whitney U-Test, **p<0.001. See also Figure S1.

Challenged mice displayed high levels of antibodies against H. pylori whole cell lysates, but not to CagA

Examining IgM and IgG responses to H. pylori (Figure 1B), control mice showed no responses, but the challenged mice had IgM responses detected as early as day 5. IgM levels declined by one month post-infection, but remained significantly elevated compared to baseline and to controls. IgG levels rose significantly 13 days post-infection compared to the controls and remained elevated throughout the experiment (Figure 1B), with cohorts 1 and 2 essentially identical; however, no antibodies against CagA were detected at any time point in any mouse (data not shown). Nevertheless, these studies provide evidence of robust immunologic recognition of H. pylori beginning soon after challenge, independent of mouse age.

Ghrelin was elevated in H. pylori-infected mice

Since gastric H. pylori colonization in humans affects circulating metabolic hormones (Francois et al., 2011; Yap et al., 2015), we examined fasting ghrelin, leptin, insulin, and peptide YY in plasma at sacrifice (Figure 1C). Ghrelin levels in control mice dropped significantly with age. In contrast, ghrelin levels of infected mice progressively rose until month 3 post-infection and diminished thereafter, with the same trend in both cohorts. No significant differences between the control and infected mice were detected for the other hormones tested (data not shown), indicating specific effects for ghrelin, the major metabolic hormone produced in the stomach.

Gastric histopathology

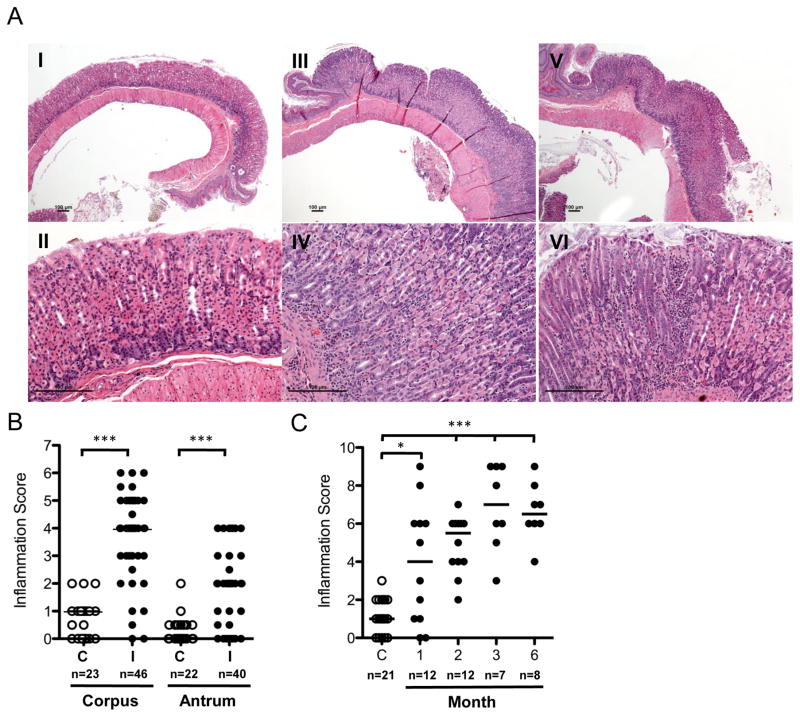

To determine whether this experimental infection elicited specific tissue responses, we evaluated gastric pathology in all animals at sacrifice. In general, the control mice displayed no inflammation, versus notable inflammatory changes in the infected mice, without significant differences between both cohorts (Figures 2A, S2). Compared to controls (Figures 2A, panels I–II; S2A), tissues from infected mice showed gastric corpus infiltration with inflammatory cells, and to a lesser extent in the antrum (Figures 2A, panels III–VI; S2B–C). The inflammatory infiltrate, consisting of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils in the lamina propria, were arranged around the gastric glands, extending in severe cases to the submucosa (Figures 2A, panels III–VI, S2C) with abundant neutrophils in the gastric pits (Figure 2A, panel VI), with inflammation sometimes pronounced adjacent to the esophageal-gastric junction (Figure S2D). In other cases, lymphoid follicles were visible (Figure S2E) in the gastric antrum (Figure S2F). Higher magnification showed a mixed inflammatory infiltrate involving gastric glands, mirroring human type B gastritis (Figure S2G–H). Rod-shaped bacteria, typical for H. pylori, were visible in several colonized animals (Figure S2I). Histopathological validation, according to the Sidney classification (Mainguet et al., 1993), showed that, as expected, scores were low in controls (Figure 2B–C), and infected mice had higher scores in both corpus and antrum (Figure 2B), trending toward more severe tissue injury at 3 and 6 months (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Histopathology and gastric inflammation scores of control and H. pylori-infected C57Bl/6 mice.

(A) Histology. (I, II) Control mice with no inflammation in the glandular stomach. (III, IV) Low- to medium-grade inflammation with abundant lymphocytes and sparse neutrophilic granulocytes in an infected mouse; representative photomicrographs were obtained from a mouse sacrificed six months post-infection; (V, VI) Severe chronic active inflammation with abundant lymphocytes and neutrophilic granulocytes in an infected mouse (three month post-infection), Upper row (I, III, V) 40× magnification, lower row (II, IV, VI) 200× magnification; Scale bars represent 100 μm. (B) Inflammation scores for antrum and corpus. C (Control), I (Infected); Active and chronic inflammation scores are combined. (C) Total inflammation scores of control and H. pylori-infected mice by month. Active and chronic inflammation of corpus and antrum are combined. n, number of mice per group in which total inflammation score was determined; Bars indicate the medians; Mann-Whitney U-Test, **p<0.02, ***p<0.0001; See also Figure S2.

H. pylori modulates immune gene expression in a tissue-specific manner

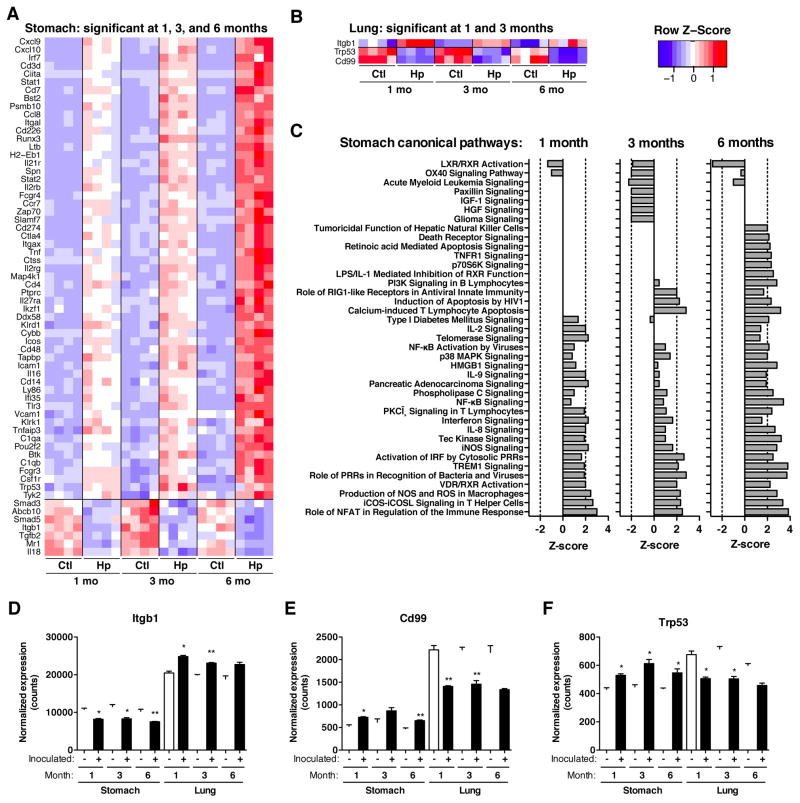

To assess the extent to which H. pylori influences immune gene expression of local and distant tissues, we examined gastric and pulmonary genes related to host immune and inflammatory responses in mice infected at 4-weeks (Cohort 1) with respect to uninfected mice. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis revealed that the major separation of samples was based on tissue location, as expected (Figure S3), and that the secondary branch points generally separated samples based on H. pylori status, with stronger effects in the stomach than in the lung. H. pylori gastric infection led to more up-regulation of immune response genes than down-regulation (Table 1). The differences in gene expression in the stomach between infected and control mice progressively increased over the course of the infection and several genes were consistently altered (Figure 3A–B, Supplemental File 1).

Table 1.

Number of immune genes with significant changes in expressiona

| Stomach | Lung | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Month | 3 Months | 6 Months | 1 Month | 3 Months | 6 Months | |

| Total | 109 | 158 | 317 | 29 | 10 | 0 |

| Up | 88 | 134 | 282 | 24 | 5 | 0 |

| Down | 21 | 24 | 35 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Shared | 1, 3 Mo | 3, 6 Mo | 1, 3, 6 Mo | 1, 3 Mo | 3, 6 Mo | 1, 3, 6 Mo |

| Total | 64 | 142 | 64 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Up | 57 | 130 | 57 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Down | 7 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Number of the 547 genes in the Nanostring (nCounter) Mouse Immunology Panel that were significantly differentially expressed, based on H. pylori-colonization status, FDR-adjusted p-value <0.5, t-test. Up and down refers to increased or decreased expression in tissue from mice colonized with H. pylori compared to controls, respectively. Shared represents genes with significant differential expression in the same direction at months 1 and 3, 3 and 6, or months 1, 3, and 6. See also Figure S4.

Figure 3. Immunologic genes consistently altered by gastric H. pylori infection in stomach and lung.

Immunologic gene expression was measured by hybridization using Nanostring (nCounter) technology in (A) gastric and (B) pulmonary tissues at 1, 3, and 6 months after colonization in Cohort 1 mice. Heat maps show expression levels of genes significantly different (FDR-adjusted p-value <0.05, t-test) at all three time points for the stomach and at 2 time points for the lung. (C) Gastric canonical pathways, significantly induced or repressed by H. pylori-infection. (D–F) Relative expression levels (normalized counts) for genes significantly different in ≥ 2 time points in each tissue. False-discovery rate adjusted p-values: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, t-test. See also Figure S3.

Genes altered in both the stomach and lung included those up-regulated in both tissues, and those regulated in opposing directions (Figures 3D–F, S3B). Using Ingenuity Pathways Analysis, up-regulated pathways, including those for T-cell activation (NFAT, iCOS, and TREM1), and pro-inflammatory molecules (nitric oxide, iNOS), were more frequent than down-regulated canonical pathways in the gastric samples from the H. pylori-infected mice, with alteration intensity generally increasing over time (Figure 3C). By 6-months post-challenge, 317 (58%) of the 547 investigated genes were significantly up-regulated (Table 1), with >10% shared at all time points studied. Apoptosis pathways were significantly up-regulated only at later time-points. In the pulmonary samples, biological functions in response to H. pylori-infection involved leukocyte development and migration, as well as T-cell differentiation (Figure S3D). Altogether, the lung and stomach have distinct H. pylori-modulated immune expression profiles.

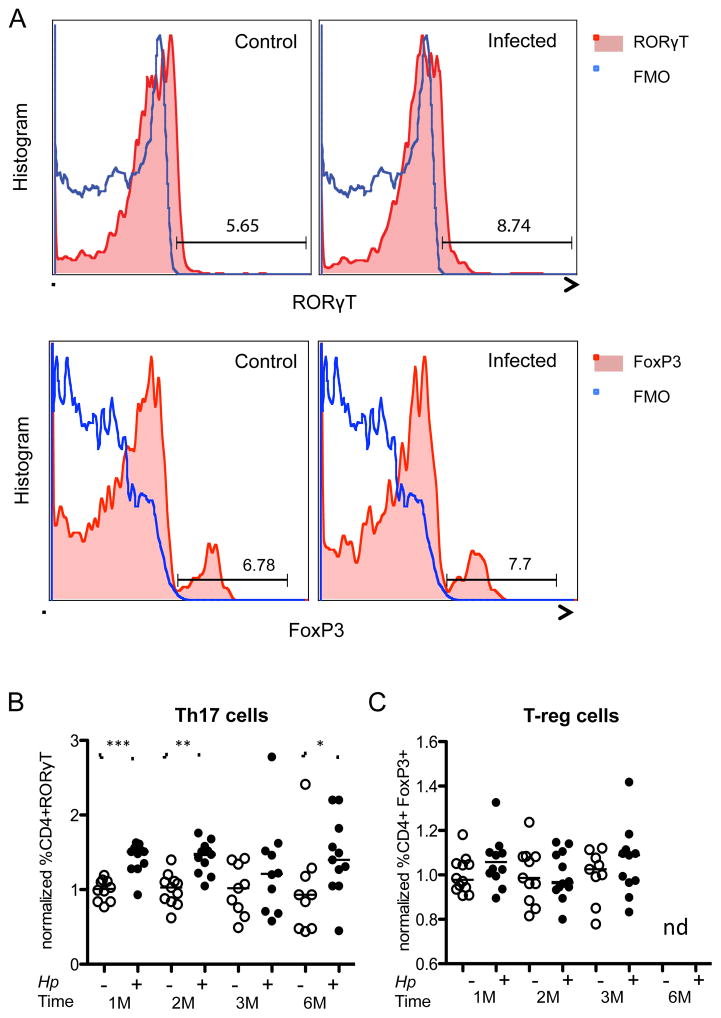

Pulmonary T-cell infiltration in H. pylori-infected mice

To further assess systemic immunologic effects of the H. pylori infection, we examined splenic and pulmonary tissues by flow cytometric analysis of CD4+ cells and their RoRγT-, IL17a-positive (Th17) and FoxP3-positive [T-regulatory; (T-reg)] subsets (Figures 4, S4). Splenic cells from infected mice trended toward increased Th17 populations, but differences were not significant. However, in the pulmonary tissues, the H. pylori-infected mice showed higher levels of CD4+ RORγT-positive cells (Figure 4B) and CD4+ IL17-positive cells at least at month 1 after infection (Figure S4) compared to controls. CD4+ FoxP3-positive (T-reg) cells did not significantly differ (Figure 4C). These effects were more prominent in the cohort infected at a younger age (Figure S4). Although effects were modest and not completely consistent over time, differential presence of CD4+ RORγT-positive cells compared to controls might provide indication of non-local immunologic effects of gastric H. pylori infection, targeting the lungs.

Figure 4. Increased proportions of CD3+ CD4+ RORγT+ cells in the lungs of H. pylori-infected mice.

(A) Gating strategy. Flow cytometry was performed on pulmonary specimens from control and H. pylori-infected mice. CD3, CD4, and CD8 surface stains and a viability stain were used to identify live T-helper cells. Nuclear staining for RORγT and FoxP3 was performed to identify Th17 and T-reg cells. A representative example of RORγT+ and FoxP3+ expression of CD4+ cells from control and infected mice is shown. Fluorescence minus one (FMO) is shown in blue in comparison to RORγT or FoxP3 shown in red; (B, C) T-cell proportions. Quantitation of the frequency of (B) CD4+ RORγT+ cells (Th17) and (C) CD4+ FoxP3+ cells (T-reg). Each mouse was normalized to the respective controls for each time point (average of controls for each month). Horizontal bars indicate group mean values. (−) Uninfected control; (+) H. pylori-infected; (M) month; Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney U-Test, *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. See also Figure S4.

H. pylori influences the gastric microbial community structure

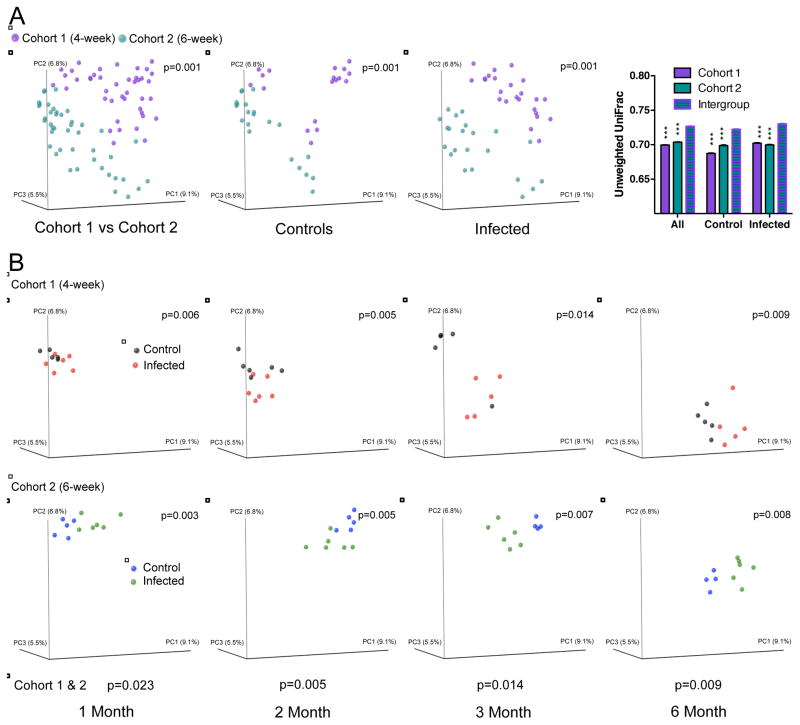

Assessing microbial diversity in the gastric samples, using the number of observed species and the Shannon index (Figure S5), there were no substantial changes over the experimental course, nor in relation to H. pylori status. Next, using UniFrac analysis, we addressed whether the community structure (β-diversity) of the two experimental cohorts varied (Figures 5, S5); reflecting founding microbial population differences common to commercially obtained mice, the two control groups differed significantly (Figure 5A), and the control and treatment groups within each cohort were more similar to each other than to the corresponding group in the other cohort. Examining the cohorts individually, control and treatment groups separated as early as one-month post-challenge (Figure 5B). For both cohorts, control and treatment samples moved monotonically over time, and remained significantly (p<0.05, ADONIS test) separated to the experiment’s end (Figures 5B, S5). Thus, H. pylori infection clearly affected the gastric microbial population structure.

Figure 5. The effect of H. pylori colonization on gastric microbial community structure.

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the unweighted UniFrac distances computed from 16S rRNA sequences from gastric samples at an even sampling (500) depth. (A) Comparison of Cohort 1 (infected at 4-weeks) and Cohort 2 (infected at 6 weeks); combined, and separated by control or infected status, respectively. Right panel shows average unweighted UniFrac distances (+/− SEM) comparing intragroup variation for the early or late cohort to the intergroup variation (early vs late), for all mice, control mice, and infected mice. ***indicates that intragroup distance is significantly different from the intergroup distance, p<0.005, t-test. (B) Cohort 1 and Cohort 2, viewed separately, over time (month 1, 2, 3 and 6). Each gastric sample is represented as a colored circle; p-values (ADONIS test) are based on unweighted UniFrac distances Significance: p-values < 0.05. See also Figure S6 and Table S5.

Relative microbial abundances in the mouse stomach are influenced by the presence of H. pylori

Although Cohorts 1 and 2 were compositionally distinct, H. pylori presence had greater impact in the younger cohort (Figure S6A). In agreement with culture and PCR results, H. pylori specific-sequences were not detected in any of the control mice, but were present in most of the infected mice over a range of three log10; relative abundance varied between 0.01% and 10% (median 0.36%) (Figure S6B) with levels similar in Cohorts 1 and 2. Comparative analysis using the LEfSe algorithm (Segata et al., 2011) via the galaxy browser revealed numerous significant abundance differences from phylum to species level (Table S1) between control and infected mice. Taxa significantly and consistently affected by the H. pylori infection (≥2 time points in the same direction) (Table S2), included 6 species belonging to five orders and six families (Bacteroidaceae, Rikenellaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, and RF39) (Table S3). To confirm our findings, we also examined taxa in a third cohort of experimentally infected mice (Cohort 3), which were all confirmed to be H. pylori-positive by culture and PCR (data not shown). In this experiment, the species and families identified as significantly different from control mice were those that also had been identified in Cohorts 1 and 2 (Table S4). In summary, these studies clearly show that H. pylori has conserved effects on the mouse gastric microbiome.

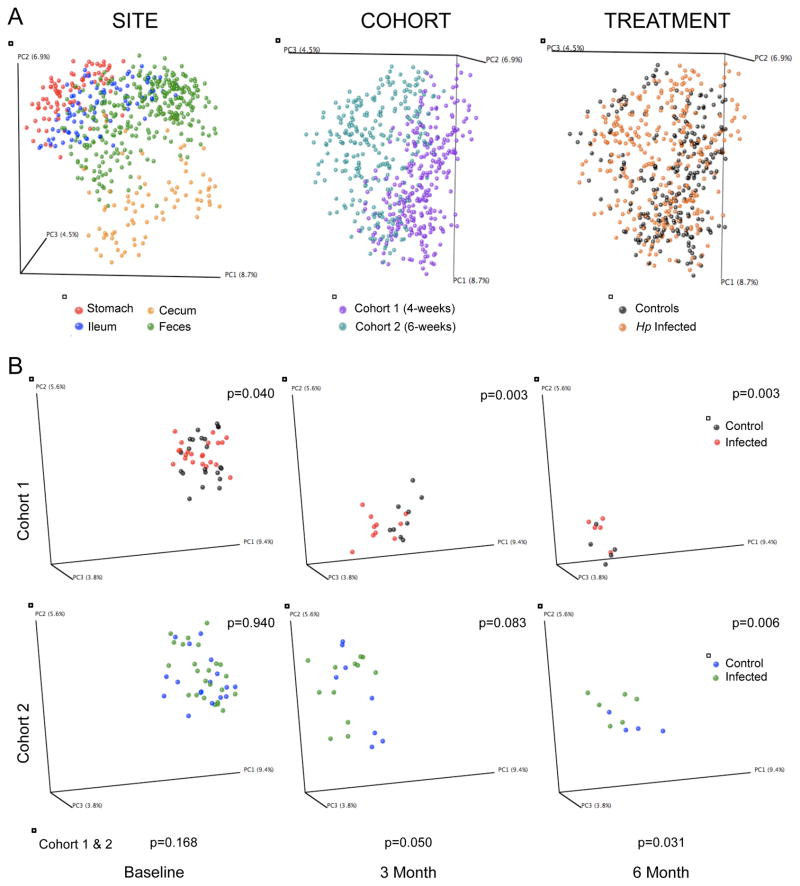

H. pylori influences intestinal microbial community structure

Next, we asked whether the presence of H. pylori in the stomach also affected downstream microbiota. Although alpha diversity increased in fecal samples as the mice aged, control and infected animals did not significantly differ (Figure S5). However, microbial community structure (β-diversity) significantly differed by intestinal locus, mouse cohort, and treatment (Figure 6A). Before H. pylori challenge (baseline), fecal samples from the subsequent control and infected mice form a single cluster. Over the course of the experiment, the fecal microbial populations in both cohorts shifted monotonically across PC1, but control and infected mice begin to significantly separate 3 months after infection (p<0.05, ADONIS test) (Figure 6B, Table S5), and the terminal cecal and ileal samples showed similar differences (Table S5). Thus, in mice, H. pylori challenge not only influences the population structure of the stomach but also more distally, with differences increasing over time.

Figure 6. The effect of H. pylori colonization on gastro-intestinal microbial community structures.

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of the unweighted UniFrac distances computed from 16S rRNA sequences at even sampling depth. (A) All samples grouped for site, age at H. pylori challenge (cohort), or treatment status and (B) fecal samples over time (baseline, month 3 and 6) of Cohort 1 and Cohort 2, respectively. Plots are organized as in the legend to Figure 5. See also Figure S6 and Table S5.

Relative microbial abundance in the mouse gut is influenced by the presence of H. pylori in the stomach

H. pylori was not detected in the mouse feces by highly sensitive PCR (data not shown), nor did high throughput sequencing detect Helicobacter-specific sequences in the fecal, ileal, and cecal samples, indicating that H. pylori effects on the intestinal microbiota was indirect. Using the LEfSe algorithm, Cohorts 1 and 2 were compositionally distinct (Figure S6B), but within each cohort, controls and infected mice differed (Table S6). We identified three species belonging to three families (Bacteroidaceae, Turicibacteraceae, and unclassified Clostridiales) that were persistently altered in the H. pylori-colonized mice (Tables S6, S7); (Turicibacter sp), also was decreased in the infected mice from Cohort 3. Analyzing ileal and cecal samples independently, we identified three persistently altered ileal Firmicutes species (Lactobacillus other, Turicibacter and Allobaculum species) and one cecal Firmicutes species (Turicibacter species) and one Tenericutes species (Anaeroplasma species); in Cohort 3 mice, features were similar (Table S4). In summary, gastric H. pylori infection and persistence affected intestinal microbial composition with conserved stable differences emerging.

DISCUSSION

Although much of the world’s population is asymptomatically colonized with H. pylori (Blaser and Atherton, 2004), risk for peptic ulcer disease and for gastric adenocarcinoma and lymphoma is increased (Kusters et al., 2006). Disease outcomes depend on H. pylori strains, host genotype, and environmental factors (e.g. salt intake) (Castano-Rodriguez et al., 2014). H. pylori is both recognized by and directs host immune responses (Arnold et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2011; Oertli et al., 2012; Robinson et al., 2007), which could have further effects on colonizing microbiota and host physiology. Both epidemiologic and experimental data provide evidence that H. pylori colonization early in life may protect against early-onset asthma (Arnold et al., 2011a; Arnold et al., 2011b; Chen and Blaser, 2007, 2008) and infections (Perry et al., 2010; Rothenbacher et al., 2000), and there is substantial clinical and epidemiologic evidence for a protective role in esophageal disease (Corley et al., 2008; Rubenstein et al., 2014; Thrift et al., 2012). Given the organism’s complex relationship with human biology, both promoting and preventing disease, animal models focusing on host and microbiota responses to H. pylori are useful.

The CagA+ H. pylori strain PMSS1 (Arnold et al., 2011b), the pre-mouse parental strain of SS1 (Lee et al., 1997), colonizes mice efficiently and induces differential immune responses and disease outcomes, based on mouse age (Arnold et al., 2011a). Low-level gastric H. pylori load in neonatal mice may reflect antimicrobial functions of mother’s milk (Minoura et al., 2005), but in any event, appears to yield tolerogenic rather than immunogenic responses (Arnold et al., 2012). We excluded possible effects of nursing by challenging post-weaned (4-week old) mice and sexually mature 6-week old mice with H. pylori. For both cohorts, we observed similar infection levels with long-term stability, and with anti-H. pylori IgM and IgG levels confirming continuing immunological recognition. As in other mouse experiments, we did not detect responses to CagA in any of the infected mice, despite the initial CagA+ functional status of PMSS1 (data not shown). It is intriguing to speculate that the lack of immunological responses to CagA may reflect cumulative effects, including low cagA-expression in the non-acidic mouse stomach (Karita et al., 1996) and/or functional loss in vivo (Arnold et al., 2011b; Barrozo et al., 2013) in which cagY variation eliminates CagA delivery to host cells (Barrozo et al., 2013).

Early in the experiment, infection levels varied substantially. Since the same strain was used, differences may have been stochastic, or reflect host (and/or microbiota) characteristics; subsequent convergence to a narrower range may reflect conserved pressures, and underscores the value of using inbred mice and a single diet. Histological evaluation of the mice, also confirming stable infection, showed corpus-dominant inflammation, mirroring typical human responses with mixed mononuclear and neutrophilic infiltrates around the gastric glands (Stolte and Meining, 2001). The intensity of the interaction also is indicated by the extent to which H. pylori influenced immune and inflammatory gastric gene expression (Table 1). Many of the genes up-regulated only late play roles in apoptosis and oncogenesis, and the increased expression of most Toll-like receptors (TLR) reflects a re-programming of innate immunity in response to H. pylori persistence. Little is known about the interplay of H. pylori with TLR3 (Pachathundikandi et al., 2015), but TLR3 and LPS-recognizing CD14 were both up-regulated throughout the study period. TLR3 recognizes dsRNA, but bacterial LPS also induces its expression (Pan et al., 2011). Dendritic cells, which play a crucial role in H. pylori recognition (Oertli and Muller, 2012; Oertli et al., 2012; Shiu and Blanchard, 2013), may modulate the evolving responses to H. pylori components.

As expected, in the absence of a local inducing agent, genes classically involved in pathogen recognition were not affected in the lung. Smad3 and Smad5 were down-regulated in the stomach by H. pylori infection, but were over-expressed at multiple time-points in the lung. Expression of the SMAD proteins, influenced by cytokines of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β family, play crucial roles in T-helper cell differentiation. Smad3 negatively regulates Th17 cell development through FoxP3 (Lu et al., 2010; Tone et al., 2008). In agreement with prior studies (Futagami et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2012; Lundgren et al., 2005), gastric T-reg and Th17 cell response-related genes (e.g., STAT3, Ccr2, Tgfb) were differentially expressed in response to H. pylori (Supplemental File 1). However, we also observed modestly higher levels of Th17 cells and a trend towards more T-reg cells in pulmonary tissues of H. pylori-infected mice, with effects enhanced in the cohort infected at a younger age. These findings provide evidence that H. pylori gastric infection might influence populations of specific immune cells in peripheral tissues, consistent with prior studies (Arnold et al., 2011a). Throughout the experiment, we observed down-regulation of IL18, important for T-reg-cell development in neonatal mice (Oertli et al., 2012), which we speculate may affect later immune responses. In adult mice, H. pylori infection usually yields Th1/Th17-dominated responses (Shi et al., 2010), but also triggers T-reg cell development, important for immune tolerance and facilitating H. pylori persistence (Arnold et al., 2011b). Th17- and T-reg-cells then also can migrate to and influence distant tissues (Lim et al., 2008), with responses affected by independent factors, including host age and genotype, and immune system development. Although it remains formally possible that during oral dosing the nasopharyngeal mucosa was damaged exposing immune cells to H. pylori, we doubt that such a scenario would occur in every mouse. We further speculate that only a chronic infection and not an acute injury can result in prolonged T-cell activation lasting several months. The differences in Th17 responses between the infected and control groups were not uniform throughout the experiment, raising the question of whether this is related to the cohort age differences or biases in flow cytometry analyses. Alternatively, this phenomenon could be due to the complex immunological cross-regulation in the lung. Although only few genes in the lung were affected consistently over time, early in the infection there were significant changes in genes, including Tgfbr1, IL4R, IL6R, and Smad3. Expression of these genes could potentially influence Th17 cell numbers or suppress IL17 production (see Supplemental file 1) (Gagliani et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2010; Tone et al., 2008).

The stomach is the major site for production of ghrelin, centrally involved in metabolic homeostasis (De Vriese and Delporte, 2007; Kojima et al., 1999). The differential ghrelin physiology in control and H. pylori-infected mice that we observed, consistent with prior studies (Bercik et al., 2009), provides further evidence of the systemic effects of gastric H. pylori. The anti-inflammatory properties of ghrelin, inhibiting Th17 cell differentiation (Xu et al., 2015), might partially explain why when levels are high (3-months), pulmonary Th17 populations are not significantly elevated. This hormonal interaction may provide H. pylori with additional means for evading host immune responses. Nevertheless, our findings confirm that H. pylori-infection is a dynamic process, involving different cytokines, receptors, and signaling molecules over an on-going temporal dimension.

Despite the relatively low H. pylori abundance in mice compared to humans, physiology and immunity were substantially affected. Because gastro-intestinal tract gene expression is influenced by other microorganisms, we asked whether H. pylori or the induced host response affects species composition locally in the stomach or distally in the intestine. Although founder effects were important drivers of the variation in bacterial community composition (Figure 6A), similar shifts in the H. pylori-positive mice, across all three cohorts, indicate conserved effects. The observed early population structure shifts could reflect changes in niche physiology (e.g. altered gastric pH, and ghrelin production), whereas later shifts might be driven by the cumulative and enhanced changes in the immune and inflammatory responses to H. pylori having systemic manifestations. Experimental approaches involving manipulation of ghrelin, gastric pH, or gastric immune responses, in isolation, could provide insight about which H. pylori-induced perturbation has the greatest effect on the microbiota. We identified taxa that were influenced by the presence of H. pylori. Although changes in the gastric microbiota were expected, we also identified taxa affected in the intestines in all three cohorts. These include members of the families Turicibacteriaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, and Desulfobirionaceae, species of which have also been linked to host immune effects (Bisson-Boutelliez et al., 2010; Devkota et al., 2012; Lukens et al., 2014; Presley et al., 2010). The potential link between changes in microbial composition due to the presence of H. pylori and the possible effects on allergic diseases requires further investigation (Fujimura and Lynch, 2015).

In conclusion, this mouse model provides evidence that gastric H. pylori infection affects local histologic, physiologic, immune, and microbiologic features, and indicates systemic effects on the distal intestinal microbiota and in the lung. The gastric niche is not isolated, and future studies are needed to extend our understanding of H. pylori colonization of humans to optimize and individualize health strategies.

METHODS

Animals Experiments

All animal experiments were performed according to an IACUC-approved protocol, with mice housed in specific pathogen-free conditions, and maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Female C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) were obtained right after weaning at 3 or at 5 weeks of age, adapted to the animal facility and then orally infected at either 4 (Cohort 1) or 6 weeks (Cohorts 2 and 3) of age. Within each cohort, there was an infected and a control group. Mice were gavaged twice (two days apart) either with 0.5 ml sterile Brucella broth or with H. pylori resuspended in Brucella broth (1×109 CFU ml−1). At month 1, 2, 3 and 6 (Cohort 3 only at month 2) after infection, mice of each cohort were fasted overnight and humanely euthanized with CO2 narcosis for specimen collection. An overview of the description of the mouse model is shown in Figure S1.

Strain recovery and histopathology

Following sacrifice, for each mouse (including controls), one longitudinal quarter of the stomach was collected for strain recovery and one for histopathology (see supplemental methods).

Measurement of H. pylori-specific antibodies and CagA antibodies in mice by Enyzme-linked immunosorbent assay

Blood was obtained from living animals by sub-mandibular bleeding or at sacrifice, and blood cells and serum was separated by centrifugation [300 g for 10 min at room temperature] and the serum was frozen. Anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) and M (IgM) levels in the mouse plasma were determined, using a modification of a method with high sensitivity and specificity for human H. pylori positivity, as described (Dubois et al., 1994). The protocol was adapted to mice by using mouse-specific IgG and IgM secondary antibodies (see supplemental methods).

Isolation of leukocytes from lungs and spleens

Spleens and lungs were dissected at sacrifice; for the lungs, the right lobe was minced with a razor blade and incubated in RPMI supplemented with 10% FCS and 0.5 mg/ml collagenase IA and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Lungs and spleens were homogenized between frosted slides in RPMI and then passed through a 40 μm nylon mesh filter (BD biosciences). Cells were pelleted at 300g for 5 minutes and red blood cells lysed by addition of ACK (Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium) lysis buffer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad CA) for 7 minutes at room temperature, then washed with RPMI, and re-suspended in Dulbecco PBS for staining.

Lymphocyte staining and analysis of lymphocyte subsets by Flow Cytometry

Cells were incubated with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue dead cell stain (Life Technologies, Grand Island NY) for 10 min at 4°C to identify live cells. Splenic and pulmonary leukocytes were identified using the following antibodies: CD3-APC-Cy™7 (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes NJ), CD4-PE-Alexa Fluor 610 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), CD8-V500 (BD Biosciences), RORγt-PE (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), Foxp3-PE-Cy7 (eBioscience) and IL17a-Alexa Flour 700 (BioLegend, San Diego CA). For staining of nuclear markers, cells were first incubated with surface antibodies (each at 1:50 in FACS buffer) along with FC block (Anti-Mouse CD16/CD32, eBioscience) at 1:200 for 30 min at 4°C, then fixed and permeabilized with Fixation/Per meabilization buffer (eBioscience) and subsequently incubated with the nuclear antibodies in Permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) for 30 min at 4°C. Prior to IL17 staining, isolated lymphocytes were cultured for 4 hours at 37°C in presence of PMA, Io nomycin, (Sigma, St. Louis MO) and GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). All cells were acquired on a LSRII (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR), with graphics and statistical tests performed using the GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA). To determine statistical significance between groups, we used the Mann Whitney Test. The applied gating strategy is shown in Figure S4. The proportion of CD4+RoRγt+, CD4+FoxP3+ and CD4+IL17a+ cells were expressed as percentages of total CD4+ cells. For each time point, the value observed in each mouse then was normalized using the mean value from control mice of each cohort and month, respectively, as denominator.

Nanostring and hormone measurements

At months 1, 3, and 6 immune gene expression of Cohort 1 mice was measured by the nCounter GX Mouse Immunology Panel (NanoString, Seattle WA). Hormones were measured in both cohorts at all time points using the Millipore Mouse Gut Hormone Panel (Millipore Corp., St. Charles MO) using a Luminex 200 (Millipore) analyzer (see supplemental methods).

DNA library preparation, sequencing and sequence analysis

DNA extraction was done using the Power Soil DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories Inc, Carlsbad, CA) and the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified and barcoded fusion primers were attached through PCR, as described (Caporaso et al., 2012). Of the 563 samples, the average depth of coverage was 3,504±3.449 sequences per sample. Six samples that had coverage below 500 reads were eliminated from the downstream analysis. Taxonomy was assigned using the open reference method in QIIME (Caporaso et al., 2010), with an RDP confidence interval of 50%, and the sequences clustered at 97% identity from the Green Genes 2013 May database release was used as a reference (McDonald et al., 2012) (see supplemental methods).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of colonization, antibody and ghrelin response, and histology scoring data was done with GraphPad Prism 5 using Mann-Whitney U-Tests or for multiple group comparisons, and Kruskal-Wallace-Tests followed by Mann-Whitney U-Test.

Accession codes

The microbial 16S rRNA data has been deposited in the SRA database under BioProject ID SRP063216.

Supplementary Material

H. pylori stably colonizes the mouse stomach over 6 months

Infected hosts recognize H. pylori antigens

H. pylori alters the population structure of the gastric and intestinal microbiota

H. pylori influences both gastric and pulmonary inflammatory gene expression

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by RO1 GM63270 from the National Institutes of Health, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Diane Belfer Program in Human Ecology (M.J.B.), the Michael Saperstein Medical Scholars Program (S.K.) and the BioTechMed Graz Program (E.L.Z.). We thank Isabel Teitler for her contributions to this work and Hao Chen for help with data deposition. This work has utilized computing resources at the High Performance Computing Facility of the Center for Health Informatics and Bioinformatics (CHIBI) at the NYU Langone Medical Center.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization and Methodology, S.K. and M.J.B.; Investigation, S.K., G.I.P.P., A.L., G.G., and X.Z.; Formal Analysis, S.K., L.M.C., and J.C.; Writing – Original Draft, S.K., L.M.C., and M.J.B.; Writing – Review & Editing, S.K., G.G., E.L.Z., and M.J.B.; Funding Acquisition, M.J.B.; Resources, E.L.Z., and M.J.B; Supervision, M.J.B.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amieva MR, Vogelmann R, Covacci A, Tompkins LS, Nelson WJ, Falkow S. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Science. 2003;300:1430–1434. doi: 10.1126/science.1081919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold IC, Dehzad N, Reuter S, Martin H, Becher B, Taube C, Muller A. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents allergic asthma in mouse models through the induction of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2011a;121:3088–3093. doi: 10.1172/JCI45041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold IC, Hitzler I, Muller A. The immunomodulatory properties of Helicobacter pylori confer protection against allergic and chronic inflammatory disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:10. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold IC, Lee JY, Amieva MR, Roers A, Flavell RA, Sparwasser T, Muller A. Tolerance rather than immunity protects from Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric preneoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2011b;140:199–209. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrozo RM, Cooke CL, Hansen LM, Lam AM, Gaddy JA, Johnson EM, Cariaga TA, Suarez G, Peek RM, Jr, Cover TL, et al. Functional plasticity in the type IV secretion system of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003189. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bercik P, Verdu EF, Foster JA, Lu J, Scharringa A, Kean I, Wang L, Blennerhassett P, Collins SM. Role of gut-brain axis in persistent abnormal feeding behavior in mice following eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R587–594. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90752.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bik EM, Eckburg PB, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Purdom EA, Francois F, Perez-Perez G, Blaser MJ, Relman DA. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:732–737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506655103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson-Boutelliez C, Massin F, Dumas D, Miller N, Lozniewski A. Desulfovibrio spp. survive within KB cells and modulate inflammatory responses. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2010;25:226–235. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2009.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, Atherton JC. Helicobacter pylori persistence: biology and disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:321–333. doi: 10.1172/JCI20925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffie CG, Bucci V, Stein RR, McKenney PT, Ling L, Gobourne A, No D, Liu H, Kinnebrew M, Viale A, et al. Precision microbiome reconstitution restores bile acid mediated resistance to Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2015;517:205–208. doi: 10.1038/nature13828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Huntley J, Fierer N, Owens SM, Betley J, Fraser L, Bauer M, et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012;6:1621–1624. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano-Rodriguez N, Kaakoush NO, Mitchell HM. Pattern-recognition receptors and gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 2014;5:336. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Helicobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:821–827. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori colonization is inversely associated with childhood asthma. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:553–560. doi: 10.1086/590158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Shoham O, Orr N, Muhsen K. An inverse and independent association between Helicobacter pylori infection and the incidence of shigellosis and other diarrheal diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:e35–42. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, Block G, Habel L, Zhao W, Leighton P, Rumore G, Quesenberry C, Buffler P, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of Barrett’s oesophagus: a community-based study. Gut. 2008;57:727–733. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.132068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vriese C, Delporte C. Influence of ghrelin on food intake and energy homeostasis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:615–619. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32829fb37c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devkota S, Wang Y, Musch MW, Leone V, Fehlner-Peach H, Nadimpalli A, Antonopoulos DA, Jabri B, Chang EB. Dietary-fat-induced taurocholic acid promotes pathobiont expansion and colitis in Il10−/− mice. Nature. 2012;487:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature11225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, Knight R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11971–11975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002601107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois A, Fiala N, Heman-Ackah LM, Drazek ES, Tarnawski A, Fishbein WN, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Natural gastric infection with Helicobacter pylori in monkeys: a model for spiral bacteria infection in humans. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1405–1417. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst PB, Gold BD. The disease spectrum of Helicobacter pylori: the immunopathogenesis of gastroduodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:615–640. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois F, Roper J, Joseph N, Pei Z, Chhada A, Shak JR, de Perez AZ, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. The effect of H. pylori eradication on meal-associated changes in plasma ghrelin and leptin. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura KE, Lynch SV. Microbiota in allergy and asthma and the emerging relationship with the gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futagami S, Hiratsuka T, Suzuki K, Kusunoki M, Wada K, Miyake K, Ohashi K, Shimizu M, Takahashi H, Gudis K, et al. gammadelta T cells increase with gastric mucosal interleukin (IL)-7, IL-1beta, and Helicobacter pylori urease specific immunoglobulin levels via CCR2 upregulation in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliani N, Vesely MC, Iseppon A, Brockmann L, Xu H, Palm NW, de Zoete MR, Licona-Limon P, Paiva RS, Ching T, et al. Th17 cells transdifferentiate into regulatory T cells during resolution of inflammation. Nature. 2015;523:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature14452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman KJ, Correa P, Tengana Aux HJ, Ramirez H, DeLany JP, Guerrero Pepinosa O, Lopez Quinones M, Collazos Parra T. Helicobacter pylori infection in the Colombian Andes: a population-based study of transmission pathways. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:290–299. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow CC, Sprent J, Fazekas de St Groth B, Vinuesa CG. Cellular and genetic mechanisms of self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435:590–597. doi: 10.1038/nature03724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins PD, Johnson LA, Luther J, Zhang M, Sauder KL, Blanco LP, Kao JY. Prior Helicobacter pylori infection ameliorates Salmonella typhimurium-induced colitis: mucosal crosstalk between stomach and distal intestine. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1398–1408. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogenauer C, Langner C, Beubler E, Lippe IT, Schicho R, Gorkiewicz G, Krause R, Gerstgrasser N, Krejs GJ, Hinterleitner TA. Klebsiella oxytoca as a causative organism of antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2418–2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science. 2012;336:1268–1273. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:159–169. doi: 10.1038/nri2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat AM, Srinivasan N, Maloy KJ. Modulation of immune development and function by intestinal microbiota. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karita M, Tummuru MK, Wirth HP, Blaser MJ. Effect of growth phase and acid shock on Helicobacter pylori cagA expression. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4501–4507. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4501-4507.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosunen TU, Aromaa A, Knekt P, Salomaa A, Rautelin H, Lohi P, Heinonen OP. Helicobacter antibodies in 1973 and 1994 in the adult population of Vammala, Finland. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:29–34. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai T, Malaty HM, Graham DY, Hosogaya S, Misawa K, Furihata K, Ota H, Sei C, Tanaka E, Akamatsu T, et al. Acquisition versus loss of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: results from an 8-year birth cohort study. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:717–721. doi: 10.1086/515376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusters JG, van Vliet AH, Kuipers EJ. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:449–490. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00054-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, O’Rourke J, De Ungria MC, Robertson B, Daskalopoulos G, Dixon MF. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1386–1397. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KS, Kalantzis A, Jackson CB, O’Connor L, Murata-Kamiya N, Hatakeyama M, Judd LM, Giraud AS, Menheniott TR. Helicobacter pylori CagA triggers expression of the bactericidal lectin REG3gamma via gastric STAT3 activation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis ND, Asim M, Barry DP, de Sablet T, Singh K, Piazuelo MB, Gobert AP, Chaturvedi R, Wilson KT. Immune evasion by Helicobacter pylori is mediated by induction of macrophage arginase II. J Immunol. 2011;186:3632–3641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HW, Lee J, Hillsamer P, Kim CH. Human Th17 cells share major trafficking receptors with both polarized effector T cells and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:122–129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Wang J, Zhang F, Chai Y, Brand D, Wang X, Horwitz DA, Shi W, Zheng SG. Role of SMAD and non-SMAD signals in the development of Th17 and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:4295–4306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens JR, Gurung P, Vogel P, Johnson GR, Carter RA, McGoldrick DJ, Bandi SR, Calabrese CR, Vande Walle L, Lamkanfi M, et al. Dietary modulation of the microbiome affects autoinflammatory disease. Nature. 2014;516:246–249. doi: 10.1038/nature13788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren A, Stromberg E, Sjoling A, Lindholm C, Enarsson K, Edebo A, Johnsson E, Suri-Payer E, Larsson P, Rudin A, et al. Mucosal FOXP3-expressing CD4+ CD25high regulatory T cells in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients. Infect Immun. 2005;73:523–531. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.523-531.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi J, Sonden B, Hurtig M, Olfat FO, Forsberg L, Roche N, Angstrom J, Larsson T, Teneberg S, Karlsson KA, et al. Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science. 2002;297:573–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1069076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainguet P, Jouret A, Haot J. The “Sidney System”, a new classification of gastritis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1993;17:T13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Contreras A, Goldfarb KC, Godoy-Vitorino F, Karaoz U, Contreras M, Blaser MJ, Brodie EL, Dominguez-Bello MG. Structure of the human gastric bacterial community in relation to Helicobacter pylori status. ISME J. 2011;5:574–579. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson JM, Rauch M, Gilmore MS. The commensal microbiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;635:15–28. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09550-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen TC, Bergh K, Waldum HL. Gastric juice: a barrier against infectious diseases. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96:94–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto960202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A, Andersen GL, Knight R, Hugenholtz P. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012;6:610–618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoura T, Kato S, Otsu S, Kodama M, Fujioka T, Iinuma K, Nishizono A. Influence of age and duration of infection on bacterial load and immune responses to Helicobacter pylori infection in a murine model. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;139:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moodley Y, Linz B, Bond RP, Nieuwoudt M, Soodyall H, Schlebusch CM, Bernhoft S, Hale J, Suerbaum S, Mugisha L, et al. Age of the association between Helicobacter pylori and man. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002693. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbreit S, Puls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertli M, Muller A. Helicobacter pylori targets dendritic cells to induce immune tolerance, promote persistence and confer protection against allergic asthma. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:566–571. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertli M, Noben M, Engler DB, Semper RP, Reuter S, Maxeiner J, Gerhard M, Taube C, Muller A. Helicobacter pylori gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and vacuolating cytotoxin promote gastric persistence and immune tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211248110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertli M, Sundquist M, Hitzler I, Engler DB, Arnold IC, Reuter S, Maxeiner J, Hansson M, Taube C, Quiding-Jarbrink M, et al. DC-derived IL-18 drives Treg differentiation, murine Helicobacter pylori-specific immune tolerance, and asthma protection. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1082–1096. doi: 10.1172/JCI61029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachathundikandi SK, Lind J, Tegtmeyer N, El-Omar EM, Backert S. Interplay of the Gastric Pathogen Helicobacter pylori with Toll-Like Receptors. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:192420. doi: 10.1155/2015/192420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan ZK, Fisher C, Li JD, Jiang Y, Huang S, Chen LY. Bacterial LPS up-regulated TLR3 expression is critical for antiviral response in human monocytes: evidence for negative regulation by CYLD. Int Immunol. 2011;23:357–364. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Perez GI, Sack RB, Reid R, Santosham M, Croll J, Blaser MJ. Transient and persistent Helicobacter pylori colonization in Native American children. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2401–2407. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2401-2407.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry S, de Jong BC, Solnick JV, de la Luz Sanchez M, Yang S, Lin PL, Hansen LM, Talat N, Hill PC, Hussain R, et al. Infection with Helicobacter pylori is associated with protection against tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presley LL, Wei B, Braun J, Borneman J. Bacteria associated with immunoregulatory cells in mice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:936–941. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01561-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid G, Younes JA, Van der Mei HC, Gloor GB, Knight R, Busscher HJ. Microbiota restoration: natural and supplemented recovery of human microbial communities. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:27–38. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K, Argent RH, Atherton JC. The inflammatory and immune response to Helicobacter pylori infection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:237–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K, Kenefeck R, Pidgeon EL, Shakib S, Patel S, Polson RJ, Zaitoun AM, Atherton JC. Helicobacter pylori-induced peptic ulcer disease is associated with inadequate regulatory T cell responses. Gut. 2008;57:1375–1385. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.137539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenbacher D, Blaser MJ, Bode G, Brenner H. Inverse relationship between gastric colonization of Helicobacter pylori and diarrheal illnesses in children: results of a population-based cross-sectional study. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1446–1449. doi: 10.1086/315887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein JH, Inadomi JM, Scheiman J, Schoenfeld P, Appelman H, Zhang M, Metko V, Kao JY. Association between Helicobacter pylori and Barrett’s esophagus, erosive esophagitis, and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Liu XF, Zhuang Y, Zhang JY, Liu T, Yin Z, Wu C, Mao XH, Jia KR, Wang FJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced Th17 responses modulate Th1 cell responses, benefit bacterial growth, and contribute to pathology in mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:5121–5129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu J, Blanchard TG. Dendritic cell function in the host response to Helicobacter pylori infection of the gastric mucosa. Pathog Dis. 2013;67:46–53. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolte M, Meining A. The updated Sydney system: classification and grading of gastritis as the basis of diagnosis and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:591–598. doi: 10.1155/2001/367832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JE, Dale A, Harding M, Coward WA, Cole TJ, Weaver LT. Helicobacter pylori colonization in early life. Pediatr Res. 1999;45:218–223. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrift AP, Pandeya N, Smith KJ, Green AC, Hayward NK, Webb PM, Whiteman DC. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risks of Barrett’s oesophagus: a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2407–2416. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tone Y, Furuuchi K, Kojima Y, Tykocinski ML, Greene MI, Tone M. Smad3 and NFAT cooperate to induce Foxp3 expression through its enhancer. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:194–202. doi: 10.1038/ni1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, Fuentes S, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, Visser CE, Kuijper EJ, Bartelsman JF, Tijssen JG, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Li Z, Yin Y, Lan H, Wang J, Zhao J, Feng J, Li Y, Zhang W. Ghrelin inhibits the differentiation of T helper 17 cells through mTOR/STAT3 signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap TW, Leow AH, Azmi AN, Francois F, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, Poh BH, Loke MF, Goh KL, Vadivelu J. Changes in Metabolic Hormones in Malaysian Young Adults following Helicobacter pylori Eradication. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.