Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated the factors associated with the receipt of fertility preservation (FP) services along the decision-making pathway in young Canadian female cancer patients. The roles of the oncologists were examined.

Methods

A total of 188 women who were diagnosed with cancer between the ages of 18–39 after the year 2000 and had finished active cancer treatment by the time of the survey (2012–2013) participated in the study. Logistic regression models and Pearson χ2 tests were used for analyses.

Results

The mean ages of participants at diagnosis and at survey time were 30.2 (SD = 3.7) and 33.9 (SD = 5.9). One quarter (n = 45, 23.9 %) did not recall having a fertility discussion with their oncologists. Of the three quarters who had a fertility discussion (n = 143, 76.1 %), discussions were equally initiated by oncologists (n = 71) and patients (n = 72). Of the 49 women (26 %) who consulted a fertility specialist, 17 (9 %) underwent a FP procedure. Fertility concern at diagnosis was the driving force of the receipt of FP services at all decision points. Our findings suggest that not only was the proactive approach of oncologists in initiating a fertility discussion important, the quality of the discussion was equally critical in the decision-making pathway.

Conclusions

Oncologists play a pivotal role in the provision of fertility services in that they are not only gate keepers, knowledge brokers, and referral initiators of FP consultation, but also they are catalysts in supporting cancer patients making important FP decision in conjunction with the consultation provided by a fertility specialist.

Keywords: Fertility preservation, Cryopreservation, Oncofertility, Oncologist-patient communication, Female cancer patients, Decision-making

Introduction

Improved ovarian stimulation protocols and advances in cryopreservation techniques have greatly increased the options for women who wish to preserve fertility prior to commencing cancer treatment [1]. Clinical practice guidelines published by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) underscore the role of oncologists in initiating fertility discussion with young cancer patients and referring concerned individuals to fertility preservation consultation (FPC) [2, 3]. Studies have shown that women who received pre-cancer treatment FPC were more able to cope with infertility stress and reproductive challenges during their cancer survivorship [4, 5]. Those who additionally took action to preserve fertility had less decisional regret [6], fewer decisional conflicts [7, 8], and higher life satisfaction [7] compared with those who chose not to proceed with fertility preservation (FP).

Despite these psychological benefits, many young female cancer patients did not receive FP services due to the lack of awareness of the fertility risks associated with their cancer treatment [9, 10] and the lack of opportunity to consult a fertility specialist of their FP options [11, 12]. Two systematic reviews conclude that the percentage of young female cancer patients being informed about fertility risks by their oncology health care providers ranges from 34 to 72 % [13] and from zero to 85 % [14], suggesting that fertility information is far from being offered routinely as recommended by ASCO. Other studies also found that FP services are severely underutilized by cancer patients, only 5–24 % of young women received a FPC prior to commencing cancer treatment [4, 6, 11, 15–18].

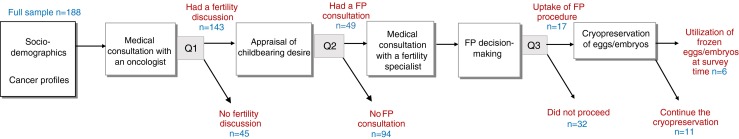

For young women who are newly diagnosed with cancer, the FP decision-making process often begins with a fertility discussion with an oncologist followed by a FPC with a fertility specialist. Along the decision-making pathway, cancer patients have to decide if they want to pursue FP given their childbearing desire, family building plan, and personal circumstance (Fig. 1). The time pressure in decision-making is often quite acute for cancer patients in order to avoid causing a life-threatening delay in initiating cancer treatment [2, 19].

Fig 1.

Fertility preservation (FP) decision-making pathway in young female cancer patients

To date, little is known about the extent to which young Canadian female cancer patients having a fertility discussion with their oncologists and receiving a FPC at the time of cancer diagnosis. The pivotal role played by oncologists in supporting Canadian cancer patients make a FP decision is not well understood. Building on existing research examining the nuances of oncologist-patient communication on fertility matters and patient experiences in accessing FP services at the time of cancer diagnosis, this study examines three questions related to the receipt of FP services in young female cancer patients along the FP decision-making pathway depicted in Fig. 1: Q1, what are the factors associated with having a fertility discussion with oncologist? Specifically, we investigate the factors associated with having an oncologist-initiated fertility discussion without patient prompting. Q2, what are the factors associated with consulting a fertility specialist following a fertility discussion with oncologist? Specifically, we investigate whether the receipt of FPC is related to the quality of pre-FPC fertility discussion with oncologist (i.e., who initiated the fertility discussion and the levels of satisfaction with the discussion). In addition, the associations between the levels of patients’ fertility concern at diagnosis and the quality of pre-FPC fertility discussion are examined. Q3, what are the factors associated with the uptake of FP procedure following a FPC? Specifically, we investigate if there is an association between the uptake of FP procedure and the quality of pre-FPC fertility discussion with oncologist.

Materials and methods

The University of Toronto’s Health Science Research Ethics Board approved the study (#27879). Eligible participants were women who were diagnosed with cancer between the ages of 18–39 after January 2000. By the time of the survey they had to have completed active cancer treatment such as chemotherapy, stem cell transplantation, and radiation. The upper age limit of 39 was chosen because FP for advanced age women have suboptimal outcomes due to age-related fertility decline and poor egg quality.

A 115-item survey with 10 open-ended questions grouped under 10 substantial sections was developed for the purpose of this study: (A) current socio-demographics and health status (12 questions), (B) cancer history and socio-demographics at the time of cancer diagnosis (9 questions), (C) motherhood status and desire for parenthood (11 questions), (D) fertility issues related to cancer care (16 questions), (E) information seeking of fertility resources (9 questions), (F) referral for FPC (11 questions), (G) FP decision-making (20 questions), (H) knowledge of fertility risks and FP services (10 questions), (I) coping and stress management (15 questions), and (J) miscellaneous (2 questions). A total of 61 questions in the questionnaire were mandatory and the remaining 54 questions were optional. Participants only had to answer the questions that were relevant to their situation. For example, sections F and G would not appear on the online questionnaire for participants who did not receive a FPC.

Among the 115 items in the questionnaire, 31 items were borrowed from 5 standardized scales with established psychometric properties: (1) Control Preference Scale [20], (2) Informed Choice Subscale from the Treatment Decision Evaluation Scale [21], (3) Satisfaction with Decision Scale [22], (4) Decision Regret Scale [23], and (5) Ways of Coping Checklist—Revision [24]. In the latter, only the Problem-Focused Coping subscale and the Self-Blamed Attribution and Avoidance subscale were used.

A survey development tool, FluidSurveys (http://fluidsurveys.com/), was used to develop the questionnaire. The cover page of the online questionnaire served as a consent form of research participation. Interested individuals could not proceed the study unless they provided consent and confirmed their eligibility by checking two boxes. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. No personal identifying information was collected in the questionnaire or tracked by the survey tool. A project website was developed to provide background information about this study. A Facebook account and a Twitter account designated for the study were created to draw attention of the research project among the cancer community in Canada.

Nine young female cancer survivors recruited through two cancer organizations1 pilot-tested the survey for content validity and readability. Minor revisions were made based on their feedback with regards to formatting, structure, clarity of questions, and inclusiveness of options in multiple choice questions. Four of them completed the revised survey two weeks afterward.

A non-probability convenience sampling was used to recruit potential participants through cancer organizations and survivor networks. An Internet search was conducted to generate a participant list of cancer organizations and groups across Canada, of which approximately 100 were identified. An invitation email was sent to all the cancer groups on the participant list to request their help in disseminating the recruitment notices through their networks. A second email to non-responding agencies was sent 2 weeks later, followed by another email after a further 3 weeks. A total of 53 cancer groups agreed to promote the study by disseminating the recruitment flyers or posting the study’s website domain and survey’s hyperlink through their channels (e.g., resource rooms, bulletin boards, newsletters, email distribution lists, websites, Facebook and Twitter). In addition, permissions were obtained from the various hospitals’ research ethics boards to post the recruitment notices on their premises.2 Participants were not directly rewarded for survey completion but were offered a monthly draw to win one of the five $20 electronic gift cards. During the data collection period from September 2012 to June 2013, approximately 250 people accessed the online survey by clicking the hyperlink. A total of 188 completed surveys were used for analyses.

Data analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0. Logistic regression with explanatory variables was used to predict the odds of having a fertility discussion with an oncologist (Q1), consulting a fertility specialist (Q2), and proceeding with FP (Q3).

For Q1, the full dataset was used to investigate the odds of having a fertility discussion. Block-entry was used in the hypothesized logistic regression model to examine the contribution of group variance related to patients’ socio-demographic characteristics at diagnosis and their cancer profiles. Seven socio-demographics variables (block 1) and 4 cancer profile variables (block 2) were selected based on FP research literature of their clinical meaningfulness and influential roles in the receipt of FP services [6, 13, 14, 16, 17, 25–29].

For Q2, only the participants who had a fertility discussion with their oncologist were included in the dataset to investigate the odds of consulting a fertility specialist. In addition to using the same 11 variables from Q1 for logistic regression analysis, a new block (block 3) with 2 variables related to the quality of fertility discussion with oncologists (i.e., who initiated the fertility discussion and the levels of satisfaction of fertility discussion) was added to the hypothesized model to better understand their contribution of variance in predicting the occurrence of event. Pearson χ2 tests were conducted to examine the associations of the initiation of fertility discussion with (a) the levels of participants’ fertility concern at diagnosis and (b) the levels of satisfaction of fertility discussion with their oncologists in order to examine their bivariate relationships.

For Q3, only participants who subsequently consulted a fertility specialist were included in the dataset to investigate the odds of the uptake of FP procedure. In addition to using the same 13 variables from Q2 for logistic regression analysis, a new variable regarding the perceived support from oncologists of the FP plan was added to the model. Due to the small sample size and the constraint of power size, bivariate logistic regression was conducted first to evaluate the magnitude of effects on the uptake of FP for each of the 14 variables. Logistic regression model was then conducted to examine the odds of proceeding with FP using only the variables that were significant at p < .05 in bivariate analyses.

The Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests in all the logistic regression models were checked first to ensure the predicted model did not differ significantly from the observed. Analysis would not continue unless the estimates fit the data at an acceptable level (p > .05). The Nagelkerke R2 was used to give an approximation about how much variance in predicting the odds of having a fertility discussion (Q1), consulting a fertility specialist (Q2) and proceeding with FP (Q3) can be explained by the hypothesized models using the explanatory variables. The changes of the Nagelkerke R2 between blocks were also calculated to measure the contribution of group variance in block-entry logistic regression models (Q1 and Q2). A 95 % confidence interval (CI) was generated for odds ratios (OR). A cutoff of p < .05 indicated statistical significance for all analyses.

Results

The characteristics of the 188 survey participants were shown in Table 1. The majority were Caucasian (n = 163, 86.7 %), heterosexual (n = 183, 97.3 %), university-educated (n = 124, 65.9 %), and Canadian-born (90.9 %). The most common cancer type was breast (n = 72, 38.3 %), followed by gynecologic (n = 39, 20.7 %), hematologic (n = 37, 19.7 %), and other malignancies (n = 40, n = 21.3 %). Fifteen (8 %) did not specify their cancer stage, 118 (62.8 %) were in stage 1 or 2, and 55 (29.3 %) were in stage 3 or 4. Nearly a quarter (n = 46, 24.5 %) received care from one oncologist only; the remaining received care from two oncologists (n = 80, 42.6 %), three oncologists (n = 51, 27.1 %), and four oncologists (n = 11, 5.9 %).

Table 1.

Logistic regression model of having a fertility discussion with oncologists (n = 188, 45 versus 143)

| All n = 188 (%) |

No discussion n = 45 (%) |

Had fertility discussion n = 143 (%) |

Model 1 OR (95 % CI) |

Model 2 OR (95 % CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: socio-demographics at diagnosisa | |||||

| Age | |||||

| Between 18 and 24 | 35 (18.6 %) | 7 (15.6 %) | 28 (19.6 %) | 1.33 (.37 to 4.82) | 1.08 (.26 to 4.59) |

| Between 25 and 29 | 43 (22.9 %) | 6 (13.3 %) | 37 (25.9 %) | 2.09 (.66 to 6.57) | 1.80 (.47 to 6.84) |

| Between 30 and 34 | 61 (32.4 %) | 19 (42.2 %) | 42 (29.4 %) | .67 (.28 to 1.6) | .41 (.14 to 1.14) |

| Between 35 and 39 | 49 (26.1 %) | 13 (28.9 %) | 36 (25.2 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 163 (86.7 %) | 38 (84.4 %) | 125 (87.4 %) | 2.01 (.69 to 5.87) | 2.61 (.81 to 8.45) |

| Non-white | 25 (13.3 %) | 7 (15.6 %) | 18 (12.6 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Residence | |||||

| Metropolitan or urban city | 134 (71.3 %) | 30 (66.7 %) | 104 (72.7 %) | 1.62 (.73 to 3.62) | 1.33 (.55 to 3.26) |

| Major town or rural area | 54 (28.7 %) | 15 (33.3 %) | 39 (27.3 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Highest education | |||||

| High school or community college | 64 (34 %) | 17 (37.8 %) | 47 (32.9 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Undergraduate or graduate degree | 124 (66 %) | 28 (62.2 %) | 96 (67.2 %) | 1.36 (.63 to 2.92) | 1.32 (.55 to 3.15) |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Income | |||||

| ≤$30,000 | 54 (28.7 %) | 12 (26.7 %) | 42 (29.4 %) | 1.70 (.54 to 5.30) | 1.44 (.40 to 5.13) |

| $30,001–$50,000 | 46 (24.5 %) | 9 (20 %) | 37 (25.9 %) | 1.88 (.68 to 5.18) | 1.65 (.54 to 5.03) |

| $50,001–$70,000 | 31 (16.5 %) | 7 (15.6 %) | 24 (16.8 %) | 1.44 (.47 to 4.40) | 1.31 (.38 to 4.55) |

| >$70,000 | 57 (30.3 %) | 17 (37.8 %) | 40 (28 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Had one or more children | |||||

| Yes | 74 (39.4 %) | 22 (48.9 %) | 52 (36.4 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No | 114 (60.6 %) | 23 (51.1 %) | 91 (63.6 %) | 1.26 (.51 to 3.10) | .91 (.32 to 2.58) |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Had a partner | |||||

| Yes | 115 (61.2 %) | 27 (60 %) | 88 (61.5 %) | .59 (.24 to 1.44) | 1.0 |

| No | 73 (38.8 %) | 18 (40 %) | 55 (38.5 %) | 1.0 | .75 (.28 to 2.0) |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Block 2: cancer profilesb | |||||

| Years since diagnosis | |||||

| ≤5 years | 147 (78.2 %) | 32 (71.1 %) | 115 (80.4 %) | – | 3.0c (1.16 to 7.60) |

| >5 years | 41 (21.8 %) | 13 (28.9 %) | 28 (19.6 %) | – | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Breast cancer | |||||

| Yes | 72 (38.3 %) | 15 (33.3 %) | 57 (39.9 %) | – | 1.30 (.53 to 3.19) |

| No | 116 (61.7 %) | 30 (66.7 %) | 86 (60.1 %) | – | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Cancer treatment types | |||||

| Chemo, radiation, or stem cell | 149 (79.3 %) | 33 (73.3 %) | 116 (81.1 %) | – | 2.04 (.78 to 5.35) |

| Surgery or others | 39 (20.7 %) | 12 (26.7 %) | 27 (18.9 %) | – | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

| Fertility concern at diagnosis (5-point Likert Scale) | – | 1.81c (1.38 to 2.38) | |||

| Not concerned at all | 27 (14.4 %) | 13 (28.9 %) | 14 (9.8 %) | ||

| Not quite concerned | 24 (12.8 %) | 7 (15.6 %) | 17 (11.9 %) | ||

| Somewhat concerned | 21 (11.2 %) | 10 (22.2 %) | 11 (7.7 %) | ||

| Quite concerned | 30 (16 %) | 6 (13.3 %) | 24 (16.8 %) | ||

| Very concerned | 86 (45.7 %) | 9 (20 %) | 77 (53.8 %) | ||

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 45 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) | ||

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

aNagelkerke R 2 for block 1 = .08

bFull model Nagelkerke R 2 = .258. Change in Nagelkerke R 2 associated with block 1 = .178

c p < .05

Participants’ mean age at diagnosis and mean current age were 30.2 (SD = 3.7) and 33.9 (SD = 5.9), respectively. One quarter (n = 45, 23.9 %) did not recall having a pre-treatment fertility discussion with their oncologist. Of the 49 (26.1 %) participants who consulted a fertility specialist, 17 (9 %) proceeded with FP: 4 women cryopreserved unfertilized oocytes, 9 cryopreserved embryos using partner sperm, 3 cryopreserved embryos using donor sperm, and 1 cryopreserved both unfertilized oocytes as well as embryos using donor sperm. At the time of survey, 6 women indicated that they were in process of attempting or had attempted a pregnancy using their cryopreserved oocytes and/or embryos, of whom one woman had a successful live birth, one had a failed outcome, and 4 were preparing to start an embryo transfer cycle. A total of 31 (16.5 %) women had a different relationship status post cancer treatment due to separation/divorce or entering into a partnered/marital relationship. Twenty-one (11.2 %) had a child born post cancer treatment.

Odds of having a fertility discussion with oncologists (n = 188, 45 vs. 143 and 117 vs. 71)

Table 1 also reports the logistic regression analysis of the odds of having a fertility discussion with oncologists. Only two variables, years since diagnosis and the degree of fertility concern at diagnosis, were found to be significant in the final model. After taking into account all other variables in the model, the odds of having a fertility discussion increases by 1.81 times (CI: 1.38 to 2.38) for each additional increment on the 5-point Likert scale examining fertility concern. Compared with women who were diagnosed more than 5 years before the data collection period from September 2012 to June 2013, the odds of having a discussion with oncologists are three times more (CI: 1.16 to 7.6) for those who were diagnosed within the past 5 years. The Nagelkerke R2 for socio-demographic characteristics at diagnosis (block 1) and cancer profiles (block 2) were .08 and .178, respectively. The final model predicts 25.8 % of the variance.

The previous logistic regression analysis was run with the same set of predictors but with a different dependent variable to analyze the odds of having an oncologist-initiated fertility discussion without patient prompting (Table 2). Unlike the results from the previous model, the degree of fertility concern was no longer a significant variable. The only significant predictor associated with increased odds of having an oncologist-initiated fertility discussion was the year since cancer diagnosis; women who received a diagnosis within the past 5 years prior to survey completion are 2.69 times more likely (CI: 1.07 to 6.74) to have a discussion compared with others who were diagnosed more than 5 years ago. The Nagelkerke R2 for socio-demographic characteristics at diagnosis (block 1) and cancer profiles (block 2) were .149 and .07, respectively. The final model explains 21 % of the variance.

Table 2.

Logistic regression model of having an oncologist-initiated fertility discussion (n = 188, 117 versus 71)

| All n = 188 (%) |

No discussion or had self-initiated discussion n = 117 (%) |

Had oncologist- initiated discussion n = 71 (%) |

Model 1 OR (95 % CI) |

Model 2 OR (95 % CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: socio-demographics at diagnosisa | |||||

| Age | |||||

| Between 18 and 24 | 35 (18.6 %) | 25 (21.4 %) | 10 (14.1 %) | .73 (.23 to 2.39) | .77 (.22 to 2.78) |

| Between 25 and 29 | 43 (22.9 %) | 25 (21.4 %) | 18 (25.4 %) | .78 (.30 to 2.03) | .78 (.28 to 2.16) |

| Between 30 and 34 | 61 (32.4 %) | 40 (34.2 %) | 21 (29.6 %) | .60 (.26 to 1.36) | .56 (.23 to 1.36) |

| Between 35 and 39 | 49 (26.1 %) | 27 (23.1 %) | 22 (31 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 163 (86.7 %) | 100 (85.5 %) | 63 (88.7 %) | 1.46 (.53 to 4.08) | 1.75 (.61 to 5.0) |

| Non-white | 25 (13.3 %) | 17 (14.5 %) | 8 (11.3 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Residence | |||||

| Metropolitan or urban city | 134 (71.3 %) | 85 (72.6 %) | 49 (69 %) | .87 (.42 to 1.79) | .89 (.42 to 1.9) |

| Major town or rural area | 54 (28.7 %) | 32 (27.4 %) | 22 (31 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Highest education | |||||

| High school or community college | 64 (34 %) | 40 (34.2 %) | 24 (33.8 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Undergraduate or graduate degree | 124 (66 %) | 77 (65.8 %) | 47 (66.2 %) | .87 (.43 to 1.76) | 1.06 (.50 to 2.22) |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Income | |||||

| ≤$30,000 | 54 (28.7 %) | 41 (35 %) | 13 (18.3 %) | .42 (.14 to 1.26) | .50 (.15 to 1.61) |

| $30,001–$50,000 | 46 (24.5 %) | 20 (17.1 %) | 26 (36.6 %) | 1.63 (.69 to 3.81) | 1.82 (.75 to 4.43) |

| $50,001–$70,000 | 31 (16.5 %) | 24 (20.5 %) | 7 (9.9 %) | .34c (.12 to .99) | .37 (.12 to 1.12) |

| >$70,000 | 57 (30.3 %) | 32 (27.4 %) | 25 (35.2 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Had one or more children | |||||

| Yes | 74 (39.4 %) | 48 (41 %) | 26 (36.6 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No | 114 (60.6 %) | 69 (59 %) | 45 (63.4 %) | 2.0 (.90 to 4.48) | 1.79 (.77 to 4.21) |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Had a partner | |||||

| Yes | 115 (61.2 %) | 65 (55.6 %) | 50 (70.4 %) | .61 (.27 to 1.36) | 1.0 |

| No | 73 (38.8 %) | 52 (44.4 %) | 21 (29.6 %) | 1.0 | .60 (.26 to 1.40) |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Block 2: cancer profilesb | |||||

| Years since diagnosis | |||||

| ≤5 years | 147 (78.2 %) | 84 (71.8 %) | 63 (88.7 %) | – | 2.69c (1.07 to 6.74) |

| >5 years | 41 (21.8 %) | 33 (28.2 %) | 8 (11.3 %) | – | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Breast cancer | |||||

| Yes | 72 (38.3 %) | 42 (35.9 %) | 30 (42.3 %) | – | .67 (.31 to 1.43) |

| No | 116 (61.7 %) | 75 (64.1 %) | 41 (57.7 %) | – | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Cancer treatment types | |||||

| Chemo, radiation, or stem cell | 149 (79.3 %) | 87 (74.4 %) | 62 (87.3 %) | – | 2.49 (.98 to 6.31) |

| Surgery or others | 39 (20.7 %) | 30 (25.6 %) | 9 (12.7 %) | – | 1.0 |

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

| Fertility concern at diagnosis (5-point Likert Scale) | – | .88 (.71 to 1.11) | |||

| Not concerned at all | 27 (14.4 %) | 15 (12.8 %) | 12 (16.9 %) | ||

| Not quite concerned | 24 (12.8 %) | 11 (9.4 %) | 13 (18.3 %) | ||

| Somewhat concerned | 21 (11.2 %) | 14 (12 %) | 7 (9.9 %) | ||

| Quite concerned | 30 (16 %) | 17 (14.5 %) | 13 (18.3 %) | ||

| Very concerned | 86 (45.7 %) | 60 (51.3 %) | 26 (36.6 %) | ||

| Total | 188 (100 %) | 117 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | ||

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

aNagelkerke R 2 for block 1 = .149

bFull model Nagelkerke R 2 = .21. Change in Nagelkerke R 2 associated with block 1 = .07

c p < .05

Odds of receiving a fertility preservation consultation (n = 143, 94 vs. 49)

Table 3 reports the characteristics of the 143 participants who had a fertility discussion with oncologists. The majority were Caucasian (n = 125, 87.4 %), heterosexual (n = 140, 97.9 %), university-educated (n = 96, 67.1 %), and Canadian-born (n = 129, 90.2 %). Their mean age at cancer diagnosis was 29.9 (SD = 5.6). The majority was childless (n = 91, 63.6 %) or in a partnered relationship (n = 88, 61.5 %).

Table 3.

Logistic regression model of consulting a fertility specialist (n = 143, 94 versus 49)

| All n = 143 (%) |

No fertility preservation consultation group n = 94 (%) |

Fertility preservation consultation group n = 49 (%) |

Model 1 OR (95 % CI) |

Model 2 OR (95 % CI) |

Model 3 OR (95 % CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: socio-demographics at diagnosisa | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| Between 18 and 24 | 28 (19.6 %) | 24 (25.5 %) | 4 (8.2 %) | .36 (.07 to 1.82) | .32 (.05 to 1.95) | .32 (.05 to 2.01) |

| Between 25 and 29 | 37 (25.9 %) | 19 (20.2 %) | 18 (36.7 %) | 2.02 (.67 to 6.04) | 2.08 (.62 to 7.00) | 2.02 (.58 to 7.06) |

| Between 30 and 34 | 42 (29.4 %) | 24 (25.5 %) | 18 (36.7 %) | 2.25 (.80 to 6.39) | 1.96 (.60 to 6.36) | 2.22 (.66 to 7.50) |

| Between 35 and 39 | 36 (25.2 %) | 27 (28.7 %) | 9 (18.4 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 125 (87.4 %) | 81 (86.2 %) | 44 (89.8 %) | 1.39 (.39 to 4.97) | 1.68 (.42 to 6.68) | 1.50 (.35 to 6.37) |

| Non-white | 18 (12.6 %) | 13 (13.8 %) | 5 (10.2 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Residence | ||||||

| Metro or urban city | 104 (72.7 %) | 66 (70.2 %) | 38 (77.6 %) | 1.29 (.52 to 3.22) | 1.48 (.53 to 4.17) | 1.28 (.43 to 3.77) |

| Major town or rural area | 39 (27.3 %) | 28 (29.8 %) | 11 (22.4 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Highest education | ||||||

| High school or community college | 47 (32.9 %) | 32 (34 %) | 15 (30.6 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Undergraduate or graduate degree | 96 (67.1 %) | 62 (66 %) | 34 (69.4 %) | .80 (.33 to 1.92) | .86 (.33 to 2.22) | .79 (.30 to 2.08) |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Income | ||||||

| ≤$30,000 | 42 (29.4) | 33 (35.1 %) | 9 (18.4 %) | .79 (.21 to 2.90) | .69 (.15 to 3.07) | .40 (.08 to 2.01) |

| $30,001–$50,000 | 37 (25.8 %) | 21 (22.3 %) | 16 (32.7 %) | 1.10 (.39 to 3.12) | 1.01 (.32 to 3.16) | 1.03 (.32 to 3.32) |

| $50,001–$70,000 | 24 (16.8 %) | 14 (14.9 %) | 10 (20.4 %) | .89 (.28 to 2.82) | .89 (.24 to 3.24) | .61 (.16 to 2.42) |

| >$70,000 | 40 (28 %) | 26 (27.7 %) | 14 (28.6 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Had one or more children | ||||||

| Yes | 52 (36.4 %) | 40 (42.6 %) | 12 (24.5 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No | 91 (63.6 %) | 54 (57.4 %) | 37 (75.5 %) | 3.64d (1.39 to 9.52) | 3.22d (1.16 to 8.93) | 4.32d (1.44 to 12.99) |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Had a partner | ||||||

| Yes | 88 (61.5 %) | 55 (58.5 %) | 33 (67.3 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No | 55 (38.5 %) | 39 (41.5 %) | 16 (32.7 %) | .66 (.27 to 1.64) | .82 (.31 to 2.22) | 1.02 (.36 to 2.94) |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Block 2: cancer profilesb | ||||||

| Years since diagnosis | ||||||

| ≤5 years | 115 (80.4 %) | 73 (77.7 %) | 42 (85.7 %) | – | 1.84 (.59 to 5.73) | 1.57 (.48 to 5.07) |

| >5 years | 28 (19.6 %) | 21 (22.3 %) | 7 (14.3 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Breast cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 57 (39.9 %) | 32 (34 %) | 25 (51 %) | – | 1.95 (.80 to 4.77) | 1.63 (.65 to 4.11) |

| No | 86 (60.1 %) | 62 (66 %) | 24 (49 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Cancer treatment types | ||||||

| Chemo, radiation, or stem cell | 116 (81.1 %) | 71 (75.5 %) | 45 (91.8 %) | – | 5.39d (1.45 to 20.09) | 8.47d (2.07 to 34.71) |

| Surgery or others | 27 (18.9 %) | 23 (24.5 %) | 4 (8.2 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Fertility concern at diagnosis (5-point Likert Scale) | – | 1.70d (1.19 to 2.44) | 1.68d (1.15 to 2.45) | |||

| Not concerned at all | 14 (9.8 %) | 13 (13.8 %) | 1 (2 %) | |||

| Not quite concerned | 17 (11.9 %) | 13 (13.8 %) | 4 (8.2 %) | |||

| Somewhat concerned | 11 (7.7 %) | 6 (6.4 %) | 5 (10.2) | |||

| Quite concerned | 24 (16.8 %) | 17 (18.1 %) | 7 (14.3 %) | |||

| Very concerned | 77 (53.8 %) | 45 (47.9 %) | 32 (65.3 %) | |||

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Block 3: quality of fertility discussion with oncologistsc | ||||||

| Who initiated the fertility discussion | ||||||

| Patient-initiated | 72 (50.3 %) | 46 (48.9 %) | 26 (53.1 %) | – | – | 1.0 |

| Oncologist-initiated | 71 (49.7 %) | 48 (51.1 %) | 23 (46.9 %) | – | – | .39 (.13 to 1.15) |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

| Levels of satisfaction of fertility discussion with oncologists | ||||||

| Dissatisfied or neutral | 80 (55.9 %) | 56 (59.6 %) | 24 (49 %) | – | – | 1.0 |

| Satisfied | 63 (44.1 %) | 38 (40.4 %) | 25 (51 %) | – | – | 3.29d (1.15 to 9.36) |

| Total | 143 (100 %) | 94 (100 %) | 49 (100 %) | |||

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

aNagelkerke R 2 for block 1 = .197

bNagelkerke R 2 for block 2 = .348. Change in Nagelkerke R 2 associated with block 1 = .151

cFull model Nagelkerke R 2 = .39. Change in Nagelkerke R 2 associated with block 2 = .04

d p < .05

Medical oncologists were involved in the fertility discussions of 97 cases (67.8 %), gynecologic oncologists in 29 cases (20.3 %), surgical oncologists in 28 cases (19.6 %), and radiation oncologists in 23 cases (16.1 %). Three quarters (n = 108, 75.5 %) had fertility discussion with one oncologist only; the remaining had fertility discussion with two oncologists (n = 25, 17.5 %) and three oncologists (n = 10, 7 %). Forty-nine women consulted a fertility specialist following a fertility discussion with their oncologists. Among those who did not receive a FPC despite having a fertility discussion with their oncologist, 43.5 % would have “definitely” or “probably” chosen to be referred if they were given a chance, and 27.2 % were uncertain, whereas 29.3 % would have probably or definitely chosen not to be referred.

Table 4 is the crosstab of the initiation of fertility discussion by participants’ satisfaction of discussion and their levels of fertility concern at cancer diagnosis. Of the 72 women (50.2 %) whose fertility discussions were self-initiated, only 1 in 4 (25 %) was satisfied with how their oncologists handled their fertility discussion. Of the 71 women (49.7 %) whose fertility discussions were initiated by their oncologists, nearly 2 in 3 (63.4 %) were satisfied with how their oncologists handled their fertility discussion. Compared with participants whose fertility discussions were initiated by their oncologist, those whose discussions were self-initiated had a significantly high level of fertility concern at diagnosis (86.1 % versus 54.9 %) [Pearson χ2 (2, n = 143) = 17.70, φ = .35], and were significantly less satisfied with the how their oncologists handled the fertility discussion (25 % vs. 63.4 %) [Pearson χ2 (2, n = 143) = 21.22, φ = .39].

Table 4.

Bivariate analyses of the initiation of fertility discussion with (a) the levels of participants’ fertility concern at diagnosis and (b) the levels of satisfaction of fertility discussion with oncologists (n = 143)

| Patient-Initiated Fertility Discussion (n = 72) |

Oncologist-Initiated Fertility Discussion (n = 71) |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fertility concern at diagnosisa | |||

| Low (1, 2) | 6 (8.3 %) | 25 (35.2 %) | 31 (21.7 %) |

| Medium (3) | 4 (5.6 %) | 7 (9.9 %) | 11 (7.7 %) |

| High (4 to 5) | 62 (86.1 %) | 39 (54.9 %) | 101 (70.6 %) |

| Total | 72 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) |

| Satisfaction of fertility discussion with oncologistsb | |||

| Dissatisfied or neutral | 54 (75 %) | 26 (36.6 %) | 80 (55.9 %) |

| Satisfied | 18 (25 %) | 45 (63.4 %) | 63 (44.1 %) |

| Total | 72 (100 %) | 71 (100 %) | 143 (100 %) |

aPearson χ 2 (2, n = 143) = 17.70, p < .001, φ = .35

bPearson χ 2 (2, n = 143) = 21.22, p < .001, φ = .39

Logistic regression analysis of the odds of receiving a FPC was shown in Table 4. The odds of receiving a FPC were significantly higher among women without children at diagnosis (OR 4.32, CI 1.44 to 12.99), those who had cancer treatment with known threats to fertility (OR 8.47, CI 2.07 to 34.71), and those who were satisfied with how their oncologists handled the fertility discussion (OR 3.29, CI 1.15 to 9.36). In addition, each increment on the 5-point Likert scale examining the fertility concern increases the odds of receiving a FPC by 1.68 times (CI 1.15 to 2.45). The Nagelkerke R2 for socio-demographic characteristics at diagnosis (block 1), cancer profiles (block 2), and fertility discussion with oncologists (block 3) were .197, .151, and .04, respectively. The final model predicts 39 % of the variance in receiving a FPC.

Odds of proceeding with fertility preservation procedure (n = 49, 32 vs. 17)

Table 5 reports the characteristics of the 49 participants who received a FPC. The majority were Caucasian (n = 44, 89.8 %), heterosexual (n = 48, 98 %), university-educated (n = 34, 69.4 %), and Canadian-born (n = 47, 95.9 %). Their mean age at cancer diagnosis was 30.22 (SD = 3.84). The majority of FPC referrals were made by medical oncologists (n = 22, 44.9 %) and surgical oncologists (n = 10, 20.4 %), followed by gynecologic oncologists (n = 6, 12.2 %), family doctors (n = 5, 10.2 %), and others (n = 6, 12.3 %). The average waiting time to see a fertility specialist was within a few days (n = 23, 46.9 %), between 1 and 2 weeks (n = 15, 30.6 %), and between 2 and 3 weeks (n = 6, 12.2 %). Five women (10.2 %) waited for more than 3 weeks to receive a FPC. Of the 25 participants (51 %) who found their oncologists supportive of their FP plan, two thirds (68 %) reported their oncologists were the one who initiated the fertility discussion, and 4 out of 5 (80 %) were satisfied with the way the fertility discussion was handled. In contrast, among the 24 participants (49 %) who found their oncologists “non-supportive” or “neutral” of their FP plan, only 1 in 5 (20.8 %) was satisfied with how their oncologist handled the fertility discussion [analyses not shown].

Table 5.

Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models of the uptake of fertility preservation procedure (n = 49, 32 versus 17)

| All n = 49 (%) |

No fertility preservation procedure group (n = 32) | Fertility preservation procedure group (n = 17) | Bivariate OR (95 % CI) |

Multivariable OR (95 % CI)a |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographics at diagnosis | |||||

| Age | |||||

| Between 18 and 24 | 4 (8.2 %) | 2 (6.3 %) | 2 (11.8 %) | 2.0 (.18 to 22.06) | – |

| Between 25 and 29 | 18 (36.7 %) | 13 (40.6 %) | 5 (29.4 %) | .77 (.14 to 4.33) | – |

| Between 30 and 34 | 18 (36.7 %) | 11 (34.4 %) | 7 (41.2 %) | 1.27 (.24 to 6.82) | – |

| Between 35 and 39 | 9 (18.4 %) | 6 (18.8 %) | 3 (17.6 %) | 1.0 | |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 44 (89.8 %) | 30 (93.8 %) | 14 (82.4 %) | .31 (.05 to 2.08) | – |

| Non-white | 5 (10.2 %) | 2 (6.3 %) | 3 (17.6 %) | 1.0 | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Residence | |||||

| Metro or urban city | 38 (77.6 %) | 24 (75 %) | 14 (82.4 %) | 1.56 (.35 to 6.84) | – |

| Major town or rural area | 11 (22.4 %) | 8 (25 %) | 3 (17.6 %) | 1.0 | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Highest education | |||||

| High school or community college | 15 (30.6 %) | 10 (31.3 %) | 5 (29.4 %) | 1.0 | – |

| Undergraduate or graduate degree | 34 (69.4 %) | 22 (68.8 %) | 12 (70.6 %) | 1.09 (.30 to 3.94) | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Income | |||||

| ≤$30,000 | 9 (18.4 %) | 4 (12.5 %) | 5 (29.4 %) | 4.58 (.73 to 28.65) | – |

| $30,001–$50,000 | 16 (32.7 %) | 11 (34.4 %) | 5 (29.4 %) | 1.67 (.32 to 8.74) | – |

| $50,001–$70,000 | 10 (20.4 %) | 6 (18.8 %) | 4 (23.5 %) | 2.44 (.41 to 14.75) | – |

| >$70,000 | 14 (28.6 %) | 11 (34.4 %) | 3 (17.6 %) | 1.0 | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Had one or more children | |||||

| Yes | 12 (24.5 %) | 11 (34.4 %) | 16 (94.1 %) | 1.0 | – |

| No | 37 (75.5 %) | 21 (65.6 %) | 1 (5.9 %) | 8.38 (.98 to 71.80) | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Had a partner | |||||

| Yes | 33 (67.3 %) | 21 (65.6 %) | 12 (70.6 %) | 1.0 | – |

| No | 16 (32.7 %) | 11 (34.4 %) | 5 (29.4 %) | .80 (.22 to 2.84) | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Cancer profiles | |||||

| Years since diagnosis | |||||

| ≤5 years | 42 (85.7 %) | 27 (84.4 %) | 15 (88.2 %) | 1.39 (.24 to 8.05) | – |

| >5 years | 7 (14.3 %) | 5 (15.6 %) | 2 (11.8 %) | 1.0 | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Breast cancer | |||||

| Yes | 25 (51 %) | 16 (50 %) | 9 (52.9 %) | 1.13 (.35 to 3.65) | – |

| No | 24 (49 %) | 16 (50 %) | 8 (47.1 %) | 1.0 | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Cancer treatment types | |||||

| Chemo, radiation or stem cell | 45 (91.8 %) | 28 (87.5 %) | 17 (100 %) | .00 | – |

| Surgery or others | 4 (8.2 %) | 4 (12.5 %) | 0 | 1.0 | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Fertility concern at diagnosis (5-point Likert Scale) | 2.89b (1.04 to 8.04) | 5.5 b (1.45 to 21.05) | |||

| Not concerned at all | 3 (6.1 %) | 3 (9.4 %) | 0 | ||

| Not quite concerned | 2 (4.1 %) | 2 (6.3 %) | 0 | ||

| Somewhat concerned | 7 (14.3 %) | 4 (12.5 %) | 3 (17.6 %) | ||

| Quite concerned | 9 (18.4 %) | 8 (25 %) | 1 (5.9 %) | ||

| Very concerned | 28 (57.1 %) | 15 (46.9 %) | 13 (76.5 %) | ||

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Quality of fertility discussion with oncologists | |||||

| Who initiated the fertility discussion | |||||

| Patient-initiated | 26 (53.1 %) | 20 (62.5 %) | 6 (35.3 %) | 1.0 | – |

| Oncologist-initiated | 23 (46.9 %) | 12 (37.5 %) | 11 (64.7 %) | 3.06 (.90 to 10.41) | – |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Levels of satisfaction of fertility discussion with oncologists | |||||

| Dissatisfied or neutral | 24 (49 %) | 20 (62.5 %) | 4 (23.5 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Satisfied | 25 (51 %) | 12 (37.5 %) | 13 (76.5 %) | 5.42b (1.43 to 20.47) | 3.4 (.60 to 19.32) |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

| Perceived support from oncologists of the FP plan | |||||

| Non-supportive or neutral | 24 (49 %) | 21 (65.6 %) | 3 (17.6 %) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Supportive | 25 (51 %) | 11 (34.4 %) | 14 (82.4 %) | 8.91b (2.1 to 37.78) | 9.61b (1.60 to 57.85) |

| Total | 49 (100 %) | 32 (100 %) | 17 (100 %) | ||

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interxval

aNagelkerke R 2 = .565

b p < .05

Table 5 also reports the results of the bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses of the uptake of FP procedure. In the bivariate logistic regression analyses, only 3 of the 14 variables were found to be significant: degree of fertility concern, the level of satisfaction of how their oncologist handled the fertility discussion and the level of perceived support from oncologist of their FP plan. Multivariable logistic regression model was then conducted using these three variables, and two of them were found to be significant in predicting the odds of proceeding with a FP procedure. Women who found their oncologists supportive of their FP plan were nine times more likely to proceed with FP compared to those who found their oncologists either non-supportive or neutral (OR 9.61, CI 1.60 to 57.85). The odds increased by more than five times for each additional increment on the 5-point Likert scale examining their fertility concern at the time of cancer diagnosis (OR 5.5, CI: 1.45 to 21.05).

Discussion

In this study, about a quarter of young women reported not having had a fertility discussion with their oncologist at the time of receiving a cancer diagnosis despite the recognized benefits for them to receive fertility information to make informed treatment decisions [2]. This is disconcerting as the majority of them were young childless women in their prime childbearing years. Nonetheless our “no discussion” rate of 24 % is comparable with the percentages reported in two other web-based surveys, where 28 % [17] and 20 % [30] of their female cancer survivors did not recall having any fertility discussion with their doctors at the time of cancer diagnosis. A US study found that fertility concerns influenced the choice of cancer treatments for almost one third of the 657 surveyed breast cancer patients [17]. Providing all necessary medical information related to cancer treatments to patients, including the side effects on fertility, is essential for informed medical decisions concerning their own health and long-term quality of life [31].

Having a fertility discussion with oncologists

The two significant factors associated with increased odds of having a fertility discussion with oncologist, irrespective of who initiated the discussion, were receiving a cancer diagnosis recently within the past 5 years before the data collection period (2012–2013) and having a high degree of fertility concern at the time of cancer diagnosis. It is quite likely that patient levels of fertility concern are highly related to their childbearing desire post treatment [17]. Perhaps women with strong desire to have (more) children are more likely to drive the discussion during the medical appointments to clarify their fertility concern [32]. It is also plausible that assertive patients who have some prior fertility knowledge may have a better chance of receiving fertility information from oncologists through inquiry. Conversely, women who are passive or emotionally preoccupied with their cancer diagnosis may not receive essential information if they do not bring up the topic themselves [33]. However, it is important to recognize that the fertility needs of young women could be easily overshadowed by their cancer diagnosis when survival takes priority [25]. Women who did not have a high fertility concern at cancer diagnosis may have lacked knowledge of fertility risks associated with their cancer treatment and may not due to a lack of desire to procreate. As fertility needs may increase over time when cancer survivors move farther away from diagnosis [31, 34] as well as changes in their personal circumstances such as relationship status, uninformed women may regret the missed opportunity to preserve their reproductive chances.

It is quite worrisome that half of the participants in this study had to initiate a fertility discussion with their oncologist when making plans for cancer treatment. Furthermore, our bivariate analysis found that whether or not the participants were satisfied with how their oncologists handled the fertility discussions was significantly associated with who initiated the fertility discussion. Similar observation was found in a Netherlands’ study [33] where one third of the female participants self-initiated the fertility discussions with their oncologists. Yet childbearing post-cancer treatment is a personal decision embedded in individual circumstance and social context; having a fertility discussion is the only way to find out a patient's family building plan and to accurately assess their interests in pursing FP [6, 16, 18].

The findings from this study suggest that a significant portion of Canadian oncologists were inattentive to the fertility needs of their patients. It is plausible that some of the fertility discussions may not have occurred if patients did not take the initiative to ask questions. One of the desired outcomes of a successful fertility intervention in oncology care is that the fertility needs of all young patients are addressed appropriately [1, 3]. Every young patient should be informed by their oncologists shortly after a cancer diagnosis is made about the fertility risks associated with their cancer treatment in order to afford them ample time to make an informed decision regarding pursuing FP [35]. Cancer patients are usually under considerable stress at the time when a life-threatening cancer diagnosis is received. It is therefore unreasonable to expect patients to initiate the fertility discussion with their oncologists in order to obtain essential fertility information [26, 27]. In keeping with the fundamental principle of equity for access to medical information, all young cancer patients of childbearing age should have an equal opportunity to receive fertility information to protect their reproductive autonomy [36–38]. The right to receive all essential medical information concerning cancer treatments, including the late side effects on their fertility, should not be contingent on self-initiation and advocacy. Further research is needed to identify discussion prompting tools (e.g., a clinical checklist, decision aids) to support oncologists in bringing up the fertility topic routinely with cancer patients without letting certain patient characteristics drive the discussion.

We also found that the levels of patient fertility concern were irrelevant when the discussion was initiated by oncologist. The only significant predictor was receiving a diagnosis recently within the past 5 years prior to survey completion. This finding is encouraging as it suggests that there is a positive shift in practice behaviors among Canadian oncologists to initiate a fertility discussion with cancer patients since the release of practice guidelines by ASCO in 2006 [2]. As oncologists choose what information to discuss during medical appointments, it is plausible that oncologists who initiated the fertility discussion with their patients were better prepared to handle their patients’ queries on fertility matters and had the resources ready to make FPC referrals, compared with oncologists who only addressed fertility issues after patient prompting [39, 40]. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the factors associated with female cancer patients having a fertility discussion that was initiated by oncologists without patient prompting. Future research should consider the use of prospective designs to observe if there is any further improvement in fertility discussion rates among Canadian oncologists.

Receiving a fertility preservation consultation

In this study, we found that only one third of the participants who had a fertility discussion with their oncologists saw a fertility specialist subsequently. Of the two thirds who did not receive a FPC, 44 % indicated that they would like to have seen a fertility specialist regarding their FP options if they were given a chance, a finding that is consistent with previous research [25, 26, 28, 41]. Prior research suggest that many young women have a strong interest in receiving FP information at the time of cancer diagnosis [26, 42]; most have favorable attitudes towards undergoing FP procedures to preserve fertility [30, 33]. Speaking to a fertility specialist on the efficacy, benefits, risks, success rates, and costs associated with cryopreservation procedures is the preferred way of obtaining personalized FP information in order to make an informed medical decision [42, 43]. By not making timely FP referrals, young women with cancer are denied their choice for informed FP decisions, potentially leading to future regret and psychological distress [44–46].

Oncologists are key knowledge brokers and gate keepers to FP services as they control what information to, or not to, discuss during medical appointments [18]. We found that higher odds of consulting a fertility specialist were associated with women who were childless, who had a higher level of fertility concern at diagnosis, whose cancer treatments had known threats to fertility, and who were satisfied with how their oncologists handled the fertility discussion. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has found a link between the quality of the oncologist-patient fertility discussions and the subsequent receipt of FPC.

A US survey on young cancer patients found that three quarters of the fertility discussions were initiated by oncologists and 68 % were satisfied with the quality of their discussion [47]. Another UK study found that most female cancer patients were dissatisfied with how their oncology providers handled the fertility discussions because of their inability to provide FP information and resources [48]. Oncologists may not be well prepared to handle patient queries on fertility matters if they are not the ones to drive the discussion. Deficiencies in FP communications, including uncertainty and lack of clarity in fertility discussion, could negatively impact patient experience and satisfaction with cancer care [18, 41, 49, 50]. Numerous studies exploring oncologist-patient communication on fertility matters found that a significant portion of female survivors recalled being dissatisfied with the quality of fertility discussion or the quantity of received information [17, 19, 27, 42, 51]. Some felt their fertility concerns were not well managed and fertility risks associated with cancer treatment were inadequately explained [28, 48].

Studies conducted in other countries have suggested that certain socio-demographic characteristics, patient factors, and cancer profiles are associated with the increased likelihood of FP referrals [4, 41]. Cancer patients who were younger [4, 16], heterosexual [16], childless [4, 16], white [4, 16], and college-educated [16] and had breast cancer [4, 11] were more likely to receive a FP referral. In this study, the receipt of FPC was not significantly associated with cancer patient relationship status at the time of diagnosis—a finding also supported by Letourneau et al. [16] but contradicted with Hill et al. [29]. Advances in freezing technologies in the past decade have greatly improved the efficacy of oocyte cryopreservation procedures with promising clinical outcomes. The American Society of Reproductive Medicine had also lifted the experimental label of oocyte cryopreservation in 2013 [52], confirming oocyte freezing is a viable FP option for cancer patients who do not have a male partner or do not wish to use donor sperm for embryo cryopreservation. In fact, a recent study also reported an increased trend of more single women being referred for pre-cancer treatment FPC for oocyte cryopreservation [11].

Uptake of fertility preservation procedure

Of the 49 women who received FPC in our study, only one third took action to preserve their fertility after consulting a fertility specialist. This percentage is substantially lower than figures reported by studies where their participants were recruited directly from FP programs affiliated with academic institutions [8, 29, 41, 53, 54]. Yet similarly low uptake rates of FP following a FPC were also reported in other studies using local cancer registries. Of the 45 women who received FP information in Armuand et al.’s study [55], only 15.6 % proceeded with FP. In another study conducted by Goodman and colleagues [4], only 27 % of the 41 women underwent a FP procedure following a FP discussion. The variation in the FP uptake rates could be due to recruitment factors, sample sizes, and participant characteristics.

Previous studies suggest that certain patient factors and socio-demographic characteristics are influential in FP decision-making. These include parity [8], relationship status [6, 29], having a strong desire for future children [6], and having a high fertility concern [6]. In this study, we found no significant differences in FP decision-making with regard to the participants’ age, ethnicity, relationship status, education, income, and cancer history, yet almost all participants who preserved fertility were childless. It is uncertain if the differences in findings between studies are due to sample composition, study location, and recruitment factors. Furthermore, we found that participants who chose to proceed with FP were more likely to be satisfied with how their oncologists handled the fertility discussion and were likely to find their oncologists supportive of their FP plan. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining the association of the quality of fertility discussion with oncologists and the subsequent uptake of FP after consulting a fertility specialist.

It is quite understandable that most cancer patients would seek medical opinions from their oncologists post FPC when their FP decision had implications on their cancer treatment plan. Latest FP studies show that many cancer patients recalled having a substantial amount of stress and time pressure during the FP decision-making process [7, 19, 29, 56] and most were influenced by the recommendations of their oncologists in decision-making [50, 57]. A study surveying cancer patients’ FPC experiences found that 79 % consulted their oncologists for decision-making after meeting with a fertility specialist but a quarter reported receiving conflictual medical advice from different health care providers [8]. Good doctor-patient fertility discussion can enhance informed decision-making and treatment satisfaction [58] but poor communication with conflictual information provided by different health care providers can negatively impact patient FP decision-making capacity by creating stress, uncertainty, confusion, and decisional conflicts, thus hindering their confidence in making satisfactory and informed medical decisions [18, 27, 28, 31].

In this study, we found that participants who reported having a negative oncologist-patient communication experience regarding fertility matters were much more inclined not to pursue FP in the end. Similarly, a study by Basting and colleagues [53] found that patients who did not feel supported by their oncologist had high decisional conflicts and post-decision regrets in their FP decision. We found evidence to show that not only was the proactivity of oncologists in initiating a fertility discussion important, but also the quality of the discussion was equally critical in supporting patients in FP decision-making. Oncologists play a pivotal role in the receipt of FP services among young female cancer patients in that they are not only gate keepers, knowledge brokers, and referral initiators of FPC, but also they are catalysts in supporting them making informed FP decision in conjunction with the FPC provided by a fertility specialist.

With the time-sensitive nature of FP procedures, oncologists play crucial roles as knowledge brokers in initiating fertility discussions with young women as soon as a cancer diagnosis is made, and as gate keepers in making early FP referrals for concerned individuals to receive timely FP services [59, 60]. A proactive approach of oncologists in the provision of FP resources, including initiating early discussion and making timely FP referrals, would give patients more FP options using established procedures [41], minimize unnecessary delay in cancer treatment to complete FP procedures [59], and yield better FP clinical outcomes [61]. Not only would early FP referrals afford patients time to have a follow-up meeting with fertility specialist [62], but also it would give patients additional time to seek input from their oncologists before making a critical FP decision that has long-term implications on their future childbearing plan [8]. Future studies should focus on evaluating the effectiveness of different training models in influencing oncology providers’ attitudes and knowledge in the provision of fertility care to cancer patients. The applicability of using various fertility preservation clinical tools, such as option grids, decision aids [33, 56, 63], prompt sheets, and clinical guidelines [1–3], to facilitate physician-patient communications under different clinical scenarios should be tested [64].

Fertility preservation in oncology is an emerging area that requires partnerships involving health providers in the areas of both oncology and reproductive medicine. In oncology practice settings, nurses and social workers can act as FP navigators or liaisons to follow through with the care plan initiated by oncologists [65, 66]. Their roles could include that of providing psychosocial care to patients and their partners who have fertility concerns, making expeditious referrals to FP programs which have experience in dealing with cancer patients, and being the liaison between the oncology and fertility preservation teams for greater integration of care across these health care settings. Of considerable importance is their role in advocating for passive cancer patients and helping them access essential fertility resources and services, such as informing them about available FP financial subsidies from non-profit organizations and government programs [35, 67].

This study has several limitations. Bias may have been introduced to the study due to cross-sectional retrospective study design, sampling frame, recruitment factors, sample composition, and methods of data analyses. First, participants recruited from cancer organizations might be more informative about fertility matters. Second, cancer survivors who opted to complete the survey in response to recruitment flyers may have had more personal interests in a research topic related to fertility and motherhood. These personal interests may have led to greater extremes in positive or negative retrospective accounts of experiences surrounding fertility discussion with oncologists. Third, the data were collected using an online survey in English language. Women with low computer literacy and less English proficiency may have chosen not to complete the online survey. Fourth, the majority of participants in our study were Caucasians or university-educated cancer survivors; sexual minority groups or immigrants were underrepresented. This sample composition may limit the generalizability of our findings to other minority groups who may encounter more barriers to accessing fertility services than mainstream population. Future work should use a more diverse patient sample to examine the utilization of FP services along the decision-making pathway. Fifth, cross-sectional design has limitation of establishing causality of variables in statistical analyses. Future prospective studies are needed to confirm the causal nature of the association between the quality of fertility discussion with oncologists and the receipt of FP services. Finally, the total number of participants who received FPC was small, which limits the power size to detect significant effects with a cutoff p value at 0.05 level in Q3. However, the majority of FPC survey studies had small sample sizes, ranging from 27 to 65 [8, 29, 53, 54, 62, 68].

This is the first Canadian study that used a national community sample to investigate the prevalence of young cancer patients in receiving FP services. One key strength of this study is the geographically diverse sample of young cancer survivors recruited from different provinces and regions across Canada. To the best of our knowledge this is the largest national dataset on examining the receipt of fertility services among young Canadian female cancer patients. The participants were recruited through the help of 53 cancer groups across Canada as well as the utilization of social media to reach out to cancer survivors who may not have otherwise been reached. In addition, the mean age of participants at the time of cancer diagnosis was 30 and most of them were in their prime years of childbearing. The average time gap between the diagnosis and survey time was only 3 years. Our sample includes a mixture of young women with different cancer diagnoses and at different cancer stages instead of using a specific patient group, such as breast cancer patients who are over-represented in fertility research [17, 27, 34, 41].

In conclusion, our findings shed new insight into understanding the pivotal role of oncologists in influencing the receipt of FP services among young female cancer patients along the decision-making pathway. Training programs are needed to increase oncologists’ sensitivity to the fertility needs of young women as well as their perceived responsibility of initiating early fertility discussions and making timely FP referrals, as recommended by ASCO, to preserve young women’s future chances of motherhood and their quality of life post treatment.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully appreciated the mentorship of Esme Fuller-Thomson PhD (supervisor), Marilyn Crawshaw PhD, Shelley L. Craig PhD, and Terry Cheng PhD from the Doctoral Thesis Committee to supervise this doctoral research study. The author was also grateful to Bradley Zebrack PhD and David Brennan PhD for their critical review of the dissertation.

The author would like to acknowledge the help from Young Adult Cancer Canada and Rethink Breast Cancer for recruiting 9 young cancer survivors to pilot test the study survey. Sincere thanks are given to the following 53 Canadian cancer groups for disseminating the recruitment flyers through their networks: Abreast of ‘bridge Cancer Survivor Dragon Boat Club Lethbridge Alberta, Bikinis for Breast Cancer, Bladder Cancer Canada, Bladder Cancer Support Group, Breast Cancer Action Kingston, Breast Cancer Action Montreal, Breast Cancer Action Nova Scotia, Breast Cancer Support Network, Breast Cancer Support Services, Breast Friends Dragon Boat Racing Team Edmonton, British Columbia Cancer Agency, Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation, Canadian Cancer Society, North West Territories Division Alberta, Canadian Cancer Society, Nova Scotia Division, Canadian Cancer Survivor Network, Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, Canadian Skin Cancer Foundation, Cancer Care Manitoba, Cancer Care Nova Scotia, Cancer Chat Canada, Cancer Fight Club, Cancer Insight Ltd, Cancer Knowledge Network, Cancerview, Colorectal Cancer Association of Canada, Compassionate Beauty, David Cornfield Melanoma Fund, Ellicsr: Health, Wellness & Cancer Survivorship Centre, Gilda’s Club Great Toronto, Gilda’s Club Simcoe Muskoka, Heart - Hope Eternal Areola Reconstructive Tattooing, Hearth Place Cancer Support Centre, Hereditary Breast & Ovarian Cancer Society of Alberta, Hereditary Breast & Ovarian Cancer Society of Montreal, Hope Spring Cancer Support Centre, Knot a Breast, Mastectomy Wear for Fighters and Survivors, Melanoma Network of Canada, Nanny Angel Network, Ovarian Cancer Canada, Peterborough’s Breast Cancer Survivor Team, Princess Margaret Hospital, Rethink Breast Cancer, Sarcoma Cancer Foundation of Canada, Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, Survive and Thrive Expedition, Surviving Beautifully, Think Pink Direct, Thrive: Physical Activity for Cancer Survivors, Thunder Bay Breast Cancer Support Group, Willow Breast Cancer Support Canada, Women’s College Hospital, and Young Adult Cancer Canada.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of Toronto’s Office of Research Ethics (#27879).

Funding

This doctoral research project was generously funded by the Ontario Graduate Scholarship, the University of Toronto Fellowship Award, and the University of Toronto Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work Doctoral Completion Award.

Footnotes

Young Adult Cancer Canada http://www.youngadultcancer.ca/ and Rethink Breast Cancer http://rethinkbreastcancer.com/

Princess Margaret Hospital, Sunnybrook Odette Cancer Centre, Toronto General Hospital, Women’s College Hospital.

Capsule

Oncologists play a pivotal role in the provision of oncofertility serivces along the decision-making pathway in young female cancer patients.

Conference presentations

The findings from this study were presented in part at the Annual Meetings of the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society (CFAS) in September 2013 and September 2014, and at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine in October 2013. The presentations received the CFAS Best Psychosocial Paper 2013, the CFAS Travel Award 2013, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Travel Award 2014.

References

- 1.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, Patrizio P, Wallace WH, Hagerty K, et al. American society of clinical oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2917–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Lindsay NB, Brennan L, Magdalinski AJ, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2500–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman LR, Balthazar U, Kim J, Mersereau JE. Trends of socioeconomic disparities in referral patterns for fertility preservation consultation. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:2076–81. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter J, Raviv L, Applegarth L, Ford JS, Josephs L, Grill E, et al. A cross-sectional study of the psychosexual impact of cancer-related infertility in women: third-party reproductive assistance. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:236–46. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Letourneau JM, Ebbel EE, Katz PP, Katz A, Ai WZ, Chien AJ, et al. Pretreatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:1710–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mersereau JE, Goodman LR, Deal AM, Gorman JR, Whitcomb BW, Su HI. To preserve or not to preserve. Cancer. 2013;119:4044–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J, Deal AM, Balthazar U, Kondapalli LA, Gracia C, Mersereau JE. Fertility preservation consultation for women with cancer: are we helping patients make high-quality decisions? Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;27:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobota A, Ozakinci G. Fertility and parenthood issues in young female cancer patients-a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:707–21. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linkeviciute A, Boniolo G, Chiavari L, Peccatori FA. Fertility preservation in cancer patients: the global framework. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:1019–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bastings L, Baysal O, Beerendonk CCM, Braat DDM, Nelen WLDM. Referral for fertility preservation counselling in female cancer patients. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:2228–37. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosen MP, Letourneau JM, Cedars MI, Melisko ME. A changing perspective: improving access to fertility preservation. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:56–60. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tschudin S, Bitzer J. Psychological aspects of fertility preservation in men and women affected by cancer and other life-threatening diseases. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:587–97. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goossens J, Delbaere I, Van Lancker A, Beeckman D, Verhaeghe S, Van Hecke A. Cancer patients' and professional caregivers' needs, preferences and factors associated with receiving and providing fertility-related information: a mixed-methods systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51:300–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geue K, Richter D, Schmidt R, Sender A, Siedentopf F, Brähler E, et al. The desire for children and fertility issues among young german cancer survivors. J Adolescent Health. 2014;54:527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letourneau JM, Smith JF, Ebbel EE, Craig A, Katz PP, Cedars MI, et al. Racial, socioeconomic, and demographic disparities in access to fertility preservation in young women diagnosed with cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:4579–88. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Partridge AH, Gelber S, Peppercorn J, Sampson E, Knudsen K, Laufer M, et al. Web-based survey of fertility issues in young women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4174–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niemasik EE, Letourneau J, Dohan D, Katz A, Melisko M, Rugo H, et al. Patient perceptions of reproductive health counseling at the time of cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of female California cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:324–32. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peate M, Meiser B, Cheah BC, Saunders C, Butow P, Thewes B, et al. Making hard choices easier: a prospective, multicentre study to assess the efficacy of a fertility-related decision aid in young women with early-stage breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1053–61. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P. The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29:21–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stalmeier PFM, Roosmalen MS, Verhoef LCG, Hoekstra-Weebers J, Oosterwijk JC, Moog U, et al. The decision evaluation scales. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Schmitt N, Rovner DR, Breer ML, Rothert ML, et al. Patient satisfaction with health care decisions: the satisfaction with decision scale. Med Decis Making. 1996;16:58–64. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brehaut JC, O'Connor AM, Wood TJ, Hack TF, Siminoff L, Gordon E, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:281–92. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03256005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cousson-Gélie F, Cosnefroy O, Christophe V, Segrestan-Crouzet C, Merckaert I, Fournier E, et al. The Ways of Coping Checklist (WCC) J Health Psychol. 2010;15:1246–56. doi: 10.1177/1359105310364438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorman JR, Usita PM, Madlensky L, Pierce JP. Young breast cancer survivors: their perspectives on treatment decisions and fertility concerns. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:32–40. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181e4528d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorman JR, Bailey S, Pierce JP, Su HI. How do you feel about fertility and parenthood? The voices of young female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:200–9. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0211-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffy CM, Allen SM, Clark MA. Discussions regarding reproductive health for young women with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:766–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penrose R, Beatty L, Mattiske J, Koczwara B. Fertility and cancer—a qualitative study of Australian cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1259–65. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1212-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hill KA, Nadler T, Mandel R, Burlein-Hall S, Librach C, Glass K, et al. Experience of young women diagnosed with breast cancer who undergo fertility preservation consultation. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012;12:127. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tschudin S, Bunting L, Abraham J, Gallop-Evans E, Fiander A, Boivin J. Correlates of fertility issues in an internet survey of cancer survivors. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31:150–7. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2010.503910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkes S, Coulson S, Crosland A, Rubin G, Stewart J. Experience of fertility preservation among younger people diagnosed with cancer. Hum Fertil. 2010;13:151–8. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2010.503359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vadaparampil ST, Christie J, Quinn GP, Fleming P, Stowe C, Bower B, et al. A pilot study to examine patient awareness and provider discussion of the impact of cancer treatment on fertility in a registry-based sample of African American women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2559–64. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1380-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garvelink MM, ter Kuile MM, Fischer MJ, Louwé LA, Hilders CGJM, Kroep JR, et al. Development of a decision aid about fertility preservation for women with breast cancer in the netherlands. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;34:170–8. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2013.851663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorman JR, Malcarne VL, Roesch SC, Madlensky L, Pierce JP. Depressive symptoms among young breast cancer survivors: the importance of reproductive concerns. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:477–85. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0768-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woodruff TK, Clayman ML, Waimey KE. Oncofertility communication: Sharing information and building relationships across disciplines. New York:Springer;2014

- 36.Nisker J. Socially based discrimination against clinically appropriate care. CMAJ. 2009;181:764. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nisker J. Letter to the editor: a national study of the provision of oncofertility services to female patients in Canada. JOGC. 2013;35:21. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(15)31043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snyder KA, Tate A. In: Woodruff TK, Clayman M, Waimey KE, editors.Oncofertility communication: Sharing information and building relationships across disciplines. New York: Springer; 2014. pp.49-60.

- 39.Yee S, Fuller-Thomson E, Lau A, Greenblatt EM. Fertility preservation practices among Ontario oncologists. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:362–8. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mersereau J. Communication between oncofertility providers and patients. In: Gracia C, Woodruff TK, editors. Oncofertility medical practice: clinical issues and implementation. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 149–60. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S, Heytens E, Moy F, Ozkavukcu S, Oktay K. Determinants of access to fertility preservation in women with breast cancer. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1932–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peate M, Meiser B, Hickey M, Friedlander M. The fertility-related concerns, needs and preferences of younger women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:215–23. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thewes B, Meiser B, Taylor A, Phillips KA, Pendlebury S, Capp A, et al. Fertility- and menopause-related information needs of younger women with a diagnosis of early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5155–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee RJ, Wakefield A, Foy S, Howell SJ, Wardley AM, Armstrong AC. Facilitating reproductive choices: the impact of health services on the experiences of young women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20:1044–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chapple A, Salinas M, Ziebland S, McPherson A, Macfarlane A. Fertility issues: the perceptions and experiences of young men recently diagnosed and treated for cancer. J Adolescent Health. 2007;40:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connell S, Patterson C, Newman B. A qualitative analysis of reproductive issues raised by young Australian women with breast cancer. Health Care Women Int. 2006;27:94–110. doi: 10.1080/07399330500377580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]