Abstract

Purpose

Ichthyosis is a rare dermato-ocular disease. This study evaluates the presenting ocular signs, symptoms, complications and prognosis of ichthyosis in a case series from Saudi Arabia.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed for 11 patients with ichthyosis who presented to King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, over the last 20 years.

Results

The most common presenting ocular diagnosis was ectropion of both the lids. Two patients developed corneal perforation with poor prognosis. Most of the patients underwent skin grafting to repair eyelid ectropion. The visual prognosis was excellent because timely surgical interventions were performed. Hence the rate of corneal complications such as perforation was low.

Conclusion

The most ocular presentation of ichthyosis is ectropion of both the upper and lower lids. Despite good visual prognosis, there were some devastating corneal complications such as perforation with unpredictable outcomes.

Keywords: Ichthyosis, Ectropion, Congenital, Skin graft, Collodion

Introduction

Ichthyosis is an inherited group of skin disorders characterized by the skin thickening and scale formation. Some of these disorders include, ichthyosis vulgaris and epidermolytic hyperkeratosis (EHK) which are autosomal dominant and lamellar type which is autosomal recessive and X-linked ichthyosis.1 Harlequin ichthyosis is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder with mutations in the abca12 gene. It is fatal and is characterized by deeply fissured skin and deformities of the hands and feet. Harlequin ichthyosis may be accompanied with lipid dysfunctions of the epidermal layer of the skin, starting prenatally, and has many names such as alligator baby and malignant keratosis.2 KID syndrome stands for keratitis, ichthyosis and sensorineural deafness. It manifests itself as alopecia, dental disorders, susceptibility to bacterial and mycotic infections and squamous cell carcinoma.3, 4 Ichthyosis with confetti is a very rare type of ichthyosis characterized by dermatological features of collodion baby mixed with patches of confetti-like healthy skin.5

The most common ocular manifestation of ichthyosis is cicatricial ectropion. We present the ocular signs, symptoms, complications and prognosis of ichthyosis in a case series from Saudi Arabia.

Patients and methods

The medical records were reviewed for all patients diagnosed with ichthyosis who presented to King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This hospital is referral based eye care hospital that treats patients nationwide and from the Gulf region. A retrospective chart review was performed for cases of ichthyosis from 1994–2014. Data were collected on patient demographics, age at presentation, type of ichthyosis, the type of referral to the hospital and if the patient was treated by a local dermatologist. Other data were collected on skin and ocular presenting signs including lid ectropion and corneal complications, the medical and surgical treatment as well as the type of the surgical procedure and the incidence of repeat lid correcting procedures such as skin grafting.

Patients were excluded if they underwent surgical repair of the lids and/or cornea that was not due to ichthyosis or if the presenting or follow-up data were insufficient.

Patients (pediatric or adults) were included if they had documented or suspected ichthyosis and documented or suspected cases of congenital lid ectropion, corneal stem cell deficiency and/or skin manifestations of ichthyosis and any cases of ichthyosis with documented histopathology studies.

The study was registered with the institutional review board and approval was obtained from the ethics committee.

Results

Eleven out of 16 patients met the inclusion criteria. Four patients were excluded because there were no physical medical records located to retrieve the data, and 1 patient had a diagnosis of orbital inflammatory syndrome not ichthyosis.

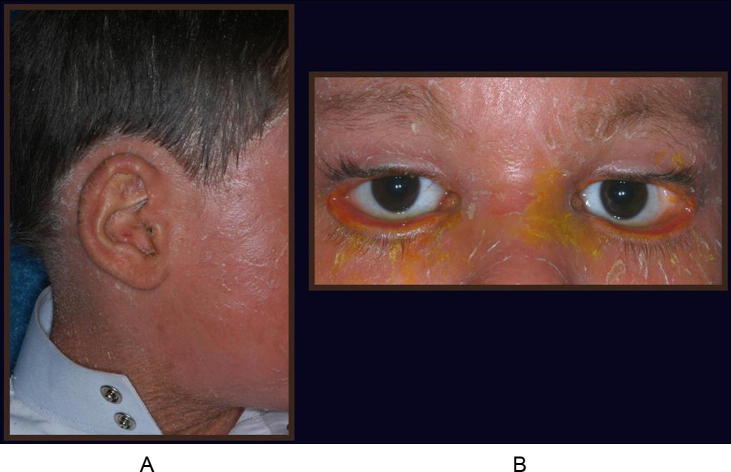

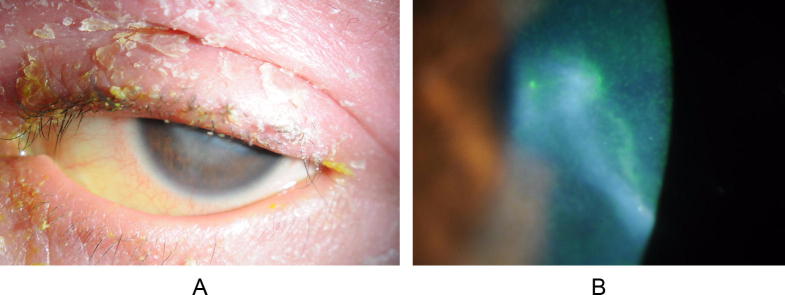

All 11 patients were referred to the hospital with a straightforward diagnosis of lid ectropion related to ichthyosis (Fig.1A and B) and exposure keratopathy (Fig.2A and B, Table 1). Eight (72%) patients had documented ichthyosis by a dermatologist, a neonatologist or an ophthalmologist. Mean age of the 11 cases was 17.4 years (range, 1.6–38 years). Mean age at presentation was 8.9 years (range, 1.6–32 years). Follow-up ranged from 3 months to 9 years.

Figure 1.

Ectropion of the upper and the lower eyelids.

Figure 2.

A child with skin crusts of the eyelids; corneal scarring and exposure keratopathy in the same patient – secondary to the lid pathology.

Table 1.

Demographic, presenting signs, treatment and prognosis of patient with ocular manifestations of ichthyosis.

| No. | Age (years) | Sex | Age at presentation | Type of ichthyosis | Visual acuity | Predominant presentation | Surgical intervention | Prognosis | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1½ | Male | 1 year | Lamellar colloidal | NA | Lid Ectropion (both U & L lids OU) + corneal perforation | Bilateral ectropion repair via skin graft Tectonic PKP |

Still in need of further lid surgery | 1 year |

| 2 | 13 | Male | 6 years | Familial Congenital Colloidal type |

20/25 OU |

Ectropion (both U & L lids OU) Exposure Keratopathy |

Skin graft | Improved | 7 years |

| 3 | 9 | Male | 5 months | Lamellar | Fixate and follow |

Ectropion (both U & L lids OU) Corneal epithelial defect |

Skin graft | Lost F/U | |

| 4 | 15 | Male | 10 years | Lamellar | 20/50 OU | Ectropion (Lower lids OU) | Skin graft | Still need lid surgery | 5 years |

| 5 | 12 | Male | 1 year | Familial | 30/100 OD |

Ectropion (L & U lids OU) Strabismus |

Skin graft (Skin regraft) None for strabismus |

Still need skin regrafting | 11 years |

| 20/30 OS | |||||||||

| 6 | 22 | Male | 11 years | NA | 20/25 OD |

Ectropion (Unspecified) Referred ichthyosis from government hospital |

NA | NA | 11 years |

| 20/30 OS | |||||||||

| 7 | 38 | Male | 32 years | Ichthyosis vulgaris | 20/60 OD |

Keratoconus Ectropion (Unspecified) |

Booked for small graft to treat corneal scarring | Lost F/U | 2 years |

| 20/40 OS | |||||||||

| 8 | 20 | Male | 15 years | NA | 20/60 OD |

Scarring Ectropion (not specified) |

Booked for skin but no healthy skin for grafting | NA | 4 years |

| 20/70 OS | |||||||||

| 9 | 21 | Female | 4 years | Lamellar | 20/25 OU | Ectropion (Lower lids OU) | Skin graft | NA Lost F/U |

3 months |

| 10 | 23 | Female | 12 years | Congenital | 20/20 OD |

Ectropion (both U & L lids OU) | Skin graft | Improved | 2½ years |

| 20/30 OS | |||||||||

| 11 | 22 | Female | 12 years | Congenital | 20/20 OD |

Ectropion (L & U lids OU) | Skin graft | Lost to follow up | 1 month |

| 20/30 OS |

OD = right eye; OS = left eye; OU = both eyes; NA = data not available, U = upper; L = lower; FU = follow-up.

At presentation, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) ranged from 20/20 to 20/25 in 6 out of 11 patients (54%) (Table 1). Two (18%) patients had vision ranging from 20/200 to count fingers secondary to corneal scarring. Three (27%) patients (all children) had fix and follow vision.

Lamellar ichthyosis was the most common type in 4 patients (36%) cases (Fig. 3, Table 1). Four (36%) patients had a positive family history for siblings with ichthyosis.

Figure 3.

Crust of the eyelid skin and ectropion – more evident on Bell’s phenomena.

All cases (100%) presented with ectropion (Table 1, Fig. 1). All patients were treated for dry eye and exposure keratopathy with different topical lubricating drops and ointment. The cornea perforated in one patient that warranted tectonic penetrating keratoplasty. The same patient developed microbial keratitis on the graft surface. Eight (72%) eyes underwent skin grafting for lid ectropion. Of the patients who did not undergo skin grafting, 1 patient had no healthy skin and was referred to a dermatologist, 1 patient was referred to a dermatologist for further skin treatment and we could not determine why the patient did not undergo skin grafting.

Three of 8 patients were recommended for skin re-grafting but only 1 underwent the procedure. One patient was sick and was lost to follow-up and the other patient’s family elected not to consent to any further surgical intervention.

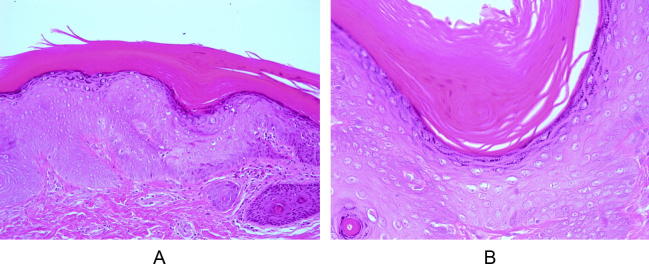

The histopathology studies were performed on excised lid skin samples during skin grafting. The results were generally consistent with the classic dermatological changes confirming the disease. Histopathologic features were, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis and/or keratotic plugging and in some cases, psoriatic epidermal hyperplasia and chronic inflammatory reaction of the dermis (Fig.4A and B).

Figure 4.

Histopathology of the skin biopsy showing thickening of the granular epidermal layer, with keratinization; areas of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis of the dermal layer.

Discussion

In this case series of ichthyosis, we found lamellar ichthyosis was the most common, with ectropion of both the upper and lower eyelids and no conjunctival involvement. We found the ocular complications from ichthyosis were not severe in the majority of cases. This observation concurs with previous reports of low ophthalmic morbidity due to ichthyosis.4 However, severe complications such as corneal perforation did occur in our case series. For example, there was one patient with a perforated cornea and limbal deformities. However, we did not perform genetic studies as the case was consistent with lamellar ichthyosis with genetic features of autosomal recessive inheritance born to first degree parents. Ichthyosis can present as part of lethal congenital syndromes with genetic mutations such as multiple sulphatase deficiency (MSD) syndrome and arthrogryposis-renal dysfunction–cholestasis (ARC) syndrome.6, 7 Hence, genetic studies should be considered based on the systemic signs and symptoms at presentation.

Ectropion was the presenting sign in all patients in our study. Some (8 of 11 cases) cases of ectropion can improve over time.8 We mainly managed ectropion with skin grafting using healthiest skin from the body or using bioengineered human skin.9 Skin grafting causes an elongation of the posterior lamellae of the eyelid resulting in good apposition of the palpebral fissure, protecting the ocular surface. Two of the remaining patients could not undergo the procedure. The youngest patient in our study was 1 year old who presented with harlequin features and corneal perforation. This patient underwent tectonic corneal graft and eyelid skin grafting on the same day. In this case the general condition of the child required critical medical care including management of skin infections, chest infections and renal problems resulting in late referral to our hospital. Successful repair of both upper eyelids of a 40 days old infant has been reported for cicatricial ectropion with harlequin ichthyosis using bioengineered human skin grafts.8 However, skin grafting may not be the first surgical option for ectropion due to unavailability of healthy skin for grafting.10 One case in our series had no healthy skin to harvest the graft. An alternate surgical technique to repair ectropion is inserting inverted sutures in the lids and the systemic use of retinoids and/or lubrication.4, 10 In this technique a double armed 4-0 vicryl suture is passed inferior to the tarsus of inferior eyelid and tied to the skin of the lid and left in place for up to 6 weeks. This surgical procedure was reported on 2 cases with excellent results for up to 4 years postoperatively.10 This technique could be a promising option in cases with severe skin changes due to ichthyosis and or failed skin grafting. Perhaps this would have been a suitable technique for our patient who did not have suitable skin for harvesting a graft and the 3 patients with primary skin graft failure.

Ocular surface changes include mild to moderate exposure keratopathy. In the current case series limbal stem cell deficiency was the most common cause of keratitis. Most of the corneal involvement was secondary to lid abnormalities such as exposure keratopathy, trichiasis and the absence of lacrimal punctum. However, there was one case of corneal ulcer which could be due to numerous factors as these patients often present with multiple risk factors including ectropion, possible corneal stem cell deficiency and/or dry eye syndrome.

Management of patients with ichthyosis requires a team approach consisting of neonatologists, dermatologists and ophthalmologists. All of our cases were referred from general hospitals for further management of the lid ectropion mainly with stable medical conditions. In these patients, extensive ocular surface lubrication was mandatory as they had severe dryness, tear deficiency and stem cell deficiency. A possible treatment option was immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine to control chronic inflammation.1, 4, 8 However, none of the cases in the current study required systemic immunosuppressives and were managed with topical lubrication and/or topical antibiotics to control concomitant ocular infections.

Limbal stem cell deficiency can cause descemetocele and corneal perforation in ichthyosis.3, 4 Tarsorrhaphy with amniotic membrane transplantation can be used to treat persistent corneal epithelial defects and even perforation.1 Tarsorrhaphy with amniotic membrane transplantation was used in 1 patient with persistent corneal epithelial defect in our series. Stem cell deficiency can be treated by combined keratoplasty and stem cell implantation. However, none of the patients in our series required this technique. One case that underwent skin grafting required tectonic penetrating keratoplasty for corneal perforation. In this case, spontaneous corneal perforation occurred after admission to an ICU for treatment of chest infections. However, in this eye with ectropion, the cornea was exposed and perforated. Although there was no documentation of corneal stem cell deficiency, it cannot be excluded as a cause of the corneal complication in this case due to the retrospective nature of our study. Unfortunately the corneal button after tectonic PKP was not evaluated for corneal changes consistent with stem cell deficiency. The histopathology features in some of our cases were similar to previous reports of ectodermal dysplasia, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis3, 4 with features of chronic inflammation and prominence of the granular layer of the epidermal layer (Fig. 4).

KKESH is a tertiary eye care center serving the entire country. Most of these cases presented late with no devastating ocular complication except one case (case 1). However, approximately half the cases (54%) presented with good vision despite the late presentation, indicating the potential of good visual outcomes after treatment. Early detection and timely treatment or referral to specialized ophthalmology centers is crucial to avoid the risk of serious ocular complications of ichthyosis. Although surgical repair of ectropion is the mainstay of treatment, there were cases managed conservatively by topical lubrication that showed significant spontaneous improvement of the ectropion.2, 8

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Saudi Ophthalmological Society, King Saud University.

References

- 1.Turgut B., Aydemir O., Kaya M., Turkcuoglu P., Demir T., Clekir U. Spontaneous corneal perforation in a patient with lamellar ichthyosis and dry eye. Clin Ophthal. 2009;3:611–613. doi: 10.2147/opth.s8407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hazuku T., Yamada K., Imaizumi M., Ikebe T., Shinoda K., Nakatsuka K. Unusual protrusion of conjunctiva in two neonates with harlequin icthyosis. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2011;2:73–77. doi: 10.1159/000325138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonda S., Uchino E., Sonda K., Yotsumoyo S., Uchio EIsashiki Y., Sakamoto T. Two patients with severe corneal disease in KID syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:181–183. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Messmer E.M., Kenyon K.R., Rittinger O., Janecke A.R., Kampik A. Ocular manifestations of Keratitis Ichthyosis Deafness (KID) syndrome. Ophthalomolgy. 2005;112:e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spoor I., Brena M., Mismaeker J., Schlipf N., Fischer J., Tadini G. The phynotypic and genotypic spectra of icthyosis with confetti plus noval genetic variation in the 3’End of KRT10 from disease to syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;151(1):64–69. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotecha U.H., Movva Sharma D., Verma J., Puri R.D., Verma I.C. Molecular evaluation of a novel missense mutation and an insertion truncating mutation in SUMF1 gene. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:55–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Y., Zhang J. Arthrogryposis-renal dysfunction–cholestasis (ARC) syndrome: from molecular genetics to clinical features. Ital J Pediatr. 2014 doi: 10.1186/s13052-014-0077-3. [online] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakraborti C., Tripathi P., Bandopadhyay G., Mazumder D.B. Congenital bilateral ectropion in lamellar ichthyosis. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2011;4(1):35–36. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.77662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Culican S., Muster P.L. Repair of cicatricial ectropion in an infant with harlequin ichthyosis using engineered human skin. Am J Ophthalmic. 2002;134:442–443. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01567-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigurdsson H., Baldursson B.T. Inverting sutures with systemic retinoid and lubrication can correct ectropion in ichthyosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstruct Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000287. Sep 11, [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]