Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the level of knowledge, attitudes, and barriers to diabetic retinopathy (DR) screening among diabetic healthcare staff at a tertiary eye hospital in central Saudi Arabia.

Methods:

This was a descriptive survey using a closed-ended questionnaire. A. 5-grade. Likert scale was used for responses to each question. Data were collected on patient demographics and the status of diabetes. Survey responses related to knowledge, attitude, and barriers were grouped.

Results:

The study sample was comprised of 45 diabetics employed at the hospital. The mean age was 49 ± 11 years and 33 diabetics were males. One-third of the study population was referred to the eye clinic for DR screening. DR screening was performed in 25% of diabetics over the previous year. Twenty-nine (64%; 95% confidence intervals: 50–78) participants had excellent knowledge of eyecare for diabetic complications. Thirteen percent of participants had a positive attitude toward periodic eye checkups. Travel distance to an eyecare unit, no referral from family physicians for annual eye checkups and the lack of availability of gender-specific eyecare professionals were the main perceived barriers.

Conclusion:

Annual DR screening needs to be promoted to primary healthcare providers and diabetic patients. Barriers should be addressed to improve the uptake of DR screening.

Keywords: Barriers, Diabetes, Diabetic Retinopathy, Knowledge Attitude and Practice

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes is a major public health problem in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. For example, there are 2.5 million diabetics in Saudi Arabia in a total population of 28 million.1 The prevalence of DM is 30% among 50 years and older Saudi population in Taif province. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy (DR) and sight-threatening DR in this province is 37% and 18% respectively.2 Hence, strategies should be implemented to detect DR in the early stages and manage them based on international standards. Early detection and treatment will reduce the visual morbidity associated with complications of diabetes. Diabetic patients are important stakeholders in this process.

Diabetic retinopathy is a sight-threatening condition that warrants timely and appropriate management. However, patients with DR may face barriers to presenting at ophthalmic clinics. This barrier need to be identified and removed. Primary healthcare staff are the best advocates of health screening to the general population.3 Their role in this initiative will depend on their level of knowledge, attitudes and practices for eyecare to diabetics. A study of South African physicians reported a 100% level of knowledge for eyecare.4 In contrast, it was 60% in Oman and 65% among medical students in Saudi Arabia.5,6 In industrialized countries, barriers exist for periodic eye checkups for diabetics. These perceived barriers differ between patients and family physicians.7

The King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital (KKESH) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia provides primary health services to nearly 4000 employees. Among them, nearly 150 suffer from diabetes.8 The employees are assessed free of cost and given medication periodically. Notably, eyecare services for DR screening are easily available to them within their workplace. Thus, cost and distances are not barriers to these individuals. In this select group of diabetic patients who work in eyecare, awareness regarding ocular complications of diabetes and the need for seeking eyecare is likely higher than diabetics in the general population. If this knowledge is lower than desired, significant action is required to improve eyecare for diabetics in Saudi Arabia. In this study, we evaluated the knowledge, attitude and perception regarding possible barriers to eyecare among diabetic patients who work in a Tertiary Eyecare Hospital in Central Saudi Arabia.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the KKESH between 2013 and 2014. Diabetic patients who attended employee health clinics were requested to participate in the study. Those who agreed were enrolled in this study. Their identities were kept confidential throughout the study. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each patient who participated in this study.

With a population of 150 diabetic healthcare staff at KKESH, we assumed that the acceptable level of knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) for eyecare was 65% of the staff with diabetes.6 For a study to have 95% confidence intervals (CI) and a 12% error margin, 45 randomly selected diabetic employees were required to participate in this study.

A chart review was performed to collect data on patient demographics and the status of diabetes and risk factors. A face-to-face interview-based questionnaire was used in this study. The first part of the questionnaire retrieved information related to the participants’ profile such as age, gender, duration of diabetes, type of diabetes, diabetes control, DR screening, optical shop visit, medical facility for eye treatment and whether or not the family physician referred the participant to an eye care specialist. The second part of the questionnaire covered responses to questions related to KAP for eyecare [Appendix 1]. This questionnaire was in English and Arabic. Participants were allowed to choose one of five responses to each question. A pilot interview was performed to ensure easy understanding of the contents of the questions. A 5-grade Likert scale was used to record patient responses.

The data were entered into a computer speadsheet using EPI Data (The EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark, Europe). Univariate analysis was performed using statistical package for social studies (SPSS 17; IBM Corp., New York, NY, USA). The sum of the responses to questions related to KAP for eyecare was grouped. For statistical validation, 95% CI were used.

RESULTS

Forty-five staff with diabetes participated in this study with a mean age of 49 ± 11 years. Seventy-three percent were males. The majority (91%) of this study sample had type II diabetes. Management for diabetes was diet control (three participants), oral hypoglycemic medicines (37 participants) and insulin (five participants). The median duration of diabetes was 4 years (standard error of mean 1-year). Six participants knew one relative who lost their eyesight due to diabetes. Nearly half of the study sample lived on campus and had access to eyecare services within 1 km.

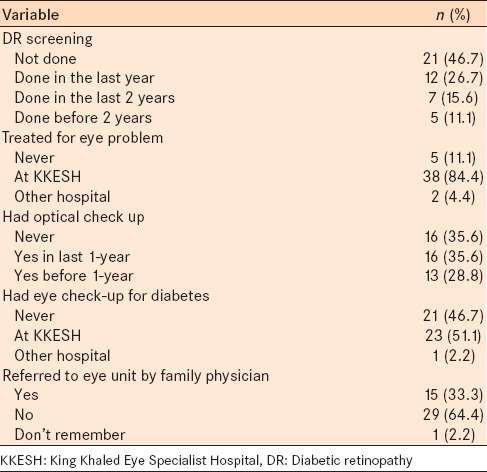

The history of seeking eyecare from ophthalmologists and optometrists over the previous year is presented in Table 1. Twenty-five percent of the participants had undergone DR screening over the previous year. Only one-third of these patients were referred to an eye clinic for DR screening.

Table 1.

Profile of diabetic staff at a tertiary eye hospital in central Saudi Arabia who participated in this study

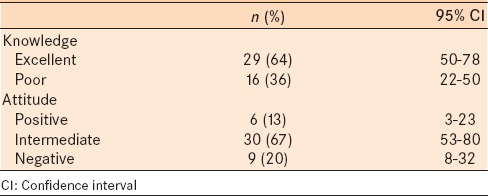

Twenty-nine participants had an excellent knowledge of the complications of diabetes based on their responses (64%; 95% CI: 50–78) participants [Table 2]. Thirteen percent of participants had a positive attitude toward periodic eye checkups.

Table 2.

Responses to knowledge related questions among diabetic staff at a tertiary eye hospital in central Saudi Arabia

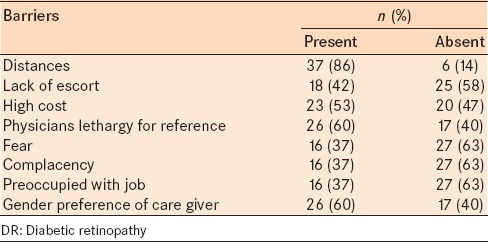

Of the 45 participants, 24 (53%) had visited eye specialists for DR screening over the previous year. DR screening among diabetics in our study was less than desired. The patient perception regarding different barriers to DR screening is presented in Table 3. Considerable commuting distance from the residence (86%), lethargy on part of a family physician toward annual referral (60%) and lack of available eyecare professionals of the same gender (60%) were the main barriers to annual DR screening.

Table 3.

Barriers for DR screening as perceived by diabetic staff of a tertiary eye hospital in central Saudi Arabia

DISCUSSION

In this study of diabetics who worked at a Tertiary Eyecare Hospital, approximately, two-thirds of participants had an excellent knowledge regarding eyecare. However, only 13% of the participants had a positive attitude towards eyecare. The barriers according to staff of a tertiary eye hospital were distances from residence to an eyecare unit, nonreferral by family physicians for an annual eye examination and lack of gender specific eyecare professionals. The fear of intervention, complacency for eyecare and with job-related stresses was the least important barriers to eyecare for diabetics in this study.

Our study evaluated a unique diabetic population. They were staff working at tertiary eye hospital, but residing at various distances from the workplace. Interestingly, half of the participants lived very close yet 86% cited distances as a barrier. Hence, distance and lack of access to eyecare were the least likely barriers. Health services for Saudi nationals are free and for other nationals are mainly offered with the support of health insurance. Hence, the cost of periodic diabetes eye screening is less likely a barrier in Saudi Arabia. Most of our participants were exposed to educational sessions regarding ocular health, blinding ophthalmic diseases and ocular complications of diabetes. Therefore, the lower level of knowledge on these topics was less than desired in this study.

The small sample in this study, although representative of the diabetic community at KKESH, precludes comparison of perceptions of barriers by subgroups. Therefore, we urge caution when extrapolating the results of our study to a different diabetic population.

Health promotion strategies should focus on imparting knowledge on the importance of annual eye screening, especially with long-standing diabetes. The lack of referral by family physicians for annual diabetes screening demonstrated that primary healthcare staffs do not judiciously follow the protocol. Improving the knowledge, attitude and perception of primary healthcare staff can be an additional strategy to increase DR screening. Placing screening facilities closer to a residence of diabetics and using telemedicine could enable the care providers to overcome the “distance” barrier.9 Mobile screening units for diabetes have been successful in developing countries with limited resources, and they could be implemented in Saudi Arabia.10

The level of knowledge regarding the importance of eyecare and annual DR screening in our study was high but less than desired from eyecare professionals and their relatives. Knowledge of annual eye screening was good in 60% of participants in a study in Indonesia.11 In another study, 17% of female diabetics were not aware about the importance of annual eye screening.12

In our study, only 25% of participants had DR screening which is low. Healthcare providers, care providers, and diabetic patients should clearly understand the difference between visits to an optical shop and a general ophthalmologist and DR screening. In Indonesia, annual eye screening among diabetics was quite low, at 15%.11 Less than half of the Indonesian diabetic patients were advised by family physicians to schedule annual eye screening.11

In our study, complacency on behalf of patients towards DR screening was a minor barrier which differs from American studies. In a study from California, USA, 27% of diabetic patients underwent DR screening despite referral by a family physician.13 In our study, the lower referral rates by family physicians for annual eye screening could explain the inability to obtain accurately responses regarding the patient's role in undergoing annual eye screening after they are referred. In India, concerns have been expressed regarding the lack of referral by family physicians for annual DR screening.14 Based on our results, adequate steps are urgently needed in Saudi Arabia to ensure adoption of a DR screening protocol at the primary healthcare levels.

Fear for DR screening was not a major barrier for annual eye screening in our study. However, fear for cataract surgery was an important barrier in a study for eye patients in the Philippines.15 It is more likely that seeking an opinion about ocular status in diabetics causes less fear than being assessed for cataract surgery. In addition, the frequent visits that diabetic patients require for annual DR screening might make them more familiar with the health provider and environment, thus, reducing fear.

More than half of participants considered cost as barrier in our study. As eyecare services to Saudi diabetics are provided free of cost, direct cost is less likely barrier in our study. Perhaps indirect costs are high and therefore perceived as a barrier. High costs (both direct and indirect) were barriers for eyecare interventions in developing countries.16,17 Further studies are needed to estimate the costs of DR screening and associate them to the uptake of DR screening in Saudi Arabia.

In our study, 27% of the participants were female and, therefore, cannot drive to an eye center on their own and have to seek support for traveling to hospital. Even among males, 60% were older than 50 years. Among these participants, perhaps the lack of an escort was the perceived barrier in our study.

Females seeking female healthcare professionals for their health care are not a new barrier. It has been practiced in many Muslim countries especially for gynecological healthcare. The preferences in adolescent patients although less strict has been noted.18 Such preferences in diabetic eyecare need to be reduced in view of large number of diabetics and challenges the health sector is facing regarding gender equity and availability of professionals.19

In summary, the benefits of annual DR screening among Saudi primary healthcare providers and diabetic patients should be actively encouraged and is urgently warranted. Saudi Arabia is facing a tsunami of diabetes, and the lifespan of diabetics is increasing, which are fundamental public healthcare issues. Identifying barriers to uptake of DR screening would further help in addressing these issues.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Employee Health Department of KKESH for their support in communicating with diabetic individuals for recruitment and motivating them to participate in this study. Mr. Ches Sorou's contribution in data entry and file collection was crucial to the success of this study. We appreciate all the participants who wholehearted contributed to this survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alhowaish AK. Economic costs of diabetes in Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med. 2013;20:1–7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.108174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Ghamdi AH, Rabiu M, Hajar S, Yorston D, Kuper H, Polack S. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness and diabetic retinopathy in Taif, Saudi Arabia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:1168–72. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-301874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crosby MI, Shuman V. Physicians’ role in eye care of patients with diabetes mellitus – Are we doing what we need to? J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111:97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman GR, Zwarenstein MF, Robinson II, Levitt NS. Staff knowledge, attitudes and practices in public sector primary care of diabetes in Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 1997;87:305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandekar R, Shah S, Al Lawatti J. Retinal examination of diabetic patients: Knowledge, attitudes and practices of physicians in Oman. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:850–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Wadaani FA. The knowledge attitude and practice regarding diabetes and diabetic retinopathy among the final year medical students of King Faisal University Medical College of Al Hasa region of Saudi Arabia: A cross sectional survey. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013;16:164–8. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.110133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartnett ME, Key IJ, Loyacano NM, Horswell RL, Desalvo KB. Perceived barriers to diabetic eye care: Qualitative study of patients and physicians. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:387–91. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kandekar R, Al-Hassan A, Al-Dhibi H, Al-Futaise M. Magnitude and determinants of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy among diabetics registered at the employee health department of a tertiary Eye Hospital of central Saudi Arabia. Oman J of Ophth. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.169889. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng M, Nathoo N, Rudnisky CJ, Tennant MT. Improving access to eye care: Teleophthalmology in Alberta, Canada. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:289–96. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohan V, Prathiba V, Pradeepa R. Tele-diabetology to screen for diabetes and associated complications in rural India: The Chunampet rural diabetes prevention project model. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2014;8:256–61. doi: 10.1177/1932296814525029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adriono G, Wang D, Octavianus C, Congdon N. Use of eye care services among diabetic patients in urban Indonesia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:930–5. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasagian-Macaulay A, Basch CE, Zybert P, Wylie-Rosett J. Ophthalmic knowledge and beliefs among women with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 1997;23:433–7. doi: 10.1177/014572179702300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saadine JB, Fong DS, Yao J. Factors associated with follow-up eye examinations among persons with diabetes. Retina. 2008;28:195–200. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318115169a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramasamy K, Raman R, Tandon M. Current state of care for diabetic retinopathy in India. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13:460–8. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Syed A, Polack S, Eusebio C, Mathenge W, Wadud Z, Mamunur AK, et al. Predictors of attendance and barriers to cataract surgery in Kenya, Bangladesh and the Philippines. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1660–7. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.748843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Song Z, Wu S, Xu K, Jin D, Wang H, et al. Outcomes and barriers to uptake of cataract surgery in rural northern China: The Heilongjiang Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014;21:161–8. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2014.903499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melese M, Alemayehu W, Friedlander E, Courtright P. Indirect costs associated with accessing eye care services as a barrier to service use in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:426–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapphahn CJ, Wilson KM, Klein JD. Adolescent girls’ and boys’ preferences for provider gender and confidentiality in their health care. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25:131–42. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alers M, van Leerdam L, Dielissen P, Lagro-Janssen A. Gendered specialities during medical education: A literature review. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3:163–78. doi: 10.1007/s40037-014-0132-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]