Abstract

Background

Forensic age estimation is requested by courts and other government authorities so that immigrants whose real age is unknown should not suffer unfair disadvantages because of their supposed age, and so that all legal procedures to which an individual’s age is relevant can be properly followed. 157 age estimations were requested in Berlin in 2014, more than twice as many as in 2004.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent articles retrieved by a selective search in the PubMed and MEDPILOT databases, supplemented by relevant recommendations and by the findings of the authors’ own research.

Results

The essential components of age estimation are the history, physical examination, X-rays of the hands, panorama films of the jaws, and, if indicated, a thin-slice CT of the medial clavicular epiphyses, provided that there is a legal basis for X-ray examinations without a medical indication. Multiple methods are always used in combination, for optimal accuracy. Depending on the legal issues at hand, the examiner may be asked to estimate the individual’s minimum age and/or his or her most probable age. The minimum-age concept can be used in determinations whether an individual has reached the age of legal majority. It is designed to ensure that practically all persons classified as adults have, in fact, attained legal majority, even though some other persons will be incorrectly classified as minors.

Conclusion

Forensic age estimation lets courts and other government authorities determine the official age of persons whose actual age is unknown—in most cases, unaccompanied refugees who may be minors. The goal is to carry out age-dependent legal procedures appropriately in accordance with the rule of law. The minimum-age concept is designed to prevent the erroneous classification of minors as legal adults.

In Germany, as in many other countries, proof of being under or over the legally defined age limits is required for legal decisions about procedural privileges or social benefits (for example, right to shelter and services of the child care facilities by youth welfare offices after taking in unaccompanied refugee minors). The relevant age limits in Germany for various legal issues range between 14 and 21 years of age (Table 1). Increasing cross-border migration has resulted in more people in Germany who can not prove their chronological age with valid identification documents. If doubts about the given age of an individual cannot be otherwise eliminated, authorities and courts can request a medical age assessment issued by an expert. In general, every physician who has the necessary expertise can be called as a medical expert. In our estimation, age assessments are prepared mainly by forensic physicians, radiologists, dentists, primary care physicians, and pediatricians. It should be noted that a medical expert is not bound under the care principle of the physician–patient relationship but is rather obliged to maintain strict neutrality.

Table 1. Legal areas, legally relevant age limits, and legal issues in Germany (for detailed comments see [e18]).

| Legal area | Age limit (n) (years) | Legal issue(s) | Legislation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criminal Law | 14 | Criminal responsibility | § 19 StGB |

| Criminal Law | 18, 21 | Applicability of youth or adult criminal law | § 1 JGG |

| Family Law | 18*1 | Guardianship | § 1773 BGB |

| Immigration Law | 16*2 | Capacity for actions and processes | § 80 AufenthG, § 12 AsylVfG |

| Social Law | 18 | Taking into care unaccompanied minors by youth welfare offices | § 42 SGB VIII |

| Social Law | 18 | Granting educational assistance | §§ 27 ff. SGB VIII |

*1For refugee minors, the question of majority age can be made according to the specifications of the country of origin.

*2The German federal government has a bill that would raise this age limit to 18 years.

A first transregional analysis of forensic age methodology was made in 1999 at the “10th Lübeck Meeting of German Forensic Physicians” (1). At this meeting, the formation of an interdisciplinary working group was suggested to standardize the as yet heterogeneous approaches used in expert reports, by developing a set of recommendations. The Study Group on Forensic Age Diagnostics (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Forensische Altersdiagnostik; AGFAD) of the German Society of Legal Medicine was founded in March 2000, and it presently has 134 members from 18 countries (2). The AGFAD recommendations for age estimations for adolescents and young adults, with or without a legal basis for X-ray examination, have been adopted (2).

Nationwide data on the number of age assessments requested annually are not available in Germany. However, in Berlin, for instance, 157 cases were requested in 2014, more than double the 73 cases requested in 2004 (3, 4).

Here we provide an overview of evidence-based methods for age assessments of adolescents and young adults, based on the most important legal principles. We further discuss the significance of expert opinions for medical age assessments. Political and ethical aspects of age assessment of unaccompanied young refugees of disputed ages are not the subject of this article.

X-ray examinations without medical indication

The nature and extent of the age assessment methods to be employed depend on whether or not a legal framework for carrying out X-ray examinations is present. According to the German X-Ray Ordinance, the use of X-rays on humans requires either medical indication or a legal basis for authorization. The German legislature has made it clear that an X-ray examination due to legal requirements also requires a justifying indication. This does not necessarily require a benefit for the health of the individual, but can also be considered as the expected benefit of the relevant laws to the public.

X-ray examinations in the context of forensic age estimation are not done for medical reasons. It is therefore necessary to examine whether a legal basis for authorization is present before carrying out X-ray examinations. In case law, different authorization grounds have been stated for X-ray examinations to assess age without medical indication (Box 1).

Box 1. Possible authorization basis, according to German law, for X-ray examinations to assess age without medical indication (for detailed comments, see [5]).

In criminal proceedings for defendants: § 81a StPO

In family court proceedings: §§ 371, 372 ZPO inspection), §§ 402 ff. ZPO (request for expert appraisal) i.V.m. §§ 26, 29, 30 FamFG

For legal procedures relating to residency: § 49 AufenthG

Related to eligibility to social benefits: § 62 SGB I

Jurisdiction independent of consent or agreement of the person examined

The case law on the question of the admissibility of X-ray examinations outside of criminal proceedings is inconsistent. However, a tendency has been observed: decisions to reject X-ray examinations for forensic age estimation are usually explained in brief, while decisions to allow X-ray examinations address the legal situation and the possibility of determining age tend to be explained in much more detail (5).

Criticisms of the legal requirements are of course legitimate, even those from the German Medical Assembly (6, 7). However, resolutions made by the German Medical Assembly express professional statements and are not legally binding (8, 9).

Using X-ray examinations for age estimation in criminal proceedings and for the Residence Act should not have detrimental health effects for the person examined. In this regard, the Administrative Court (VG) Hamburg (Az. 3 E 1152/09) stated, already in 2009, that this requirement should be interpreted to indicate that “in accordance with the principle of proportionality, X-ray irradiation is a health hazard within the normal range, and not a health disadvantage in the meaning of the provision, for the person examined.”

In Table 2, the effective radiation doses of X-ray procedures used for age assessment are listed. These doses are far below the natural effective doses in Germany, which amounts to an average of 2.1 mSv, and in some regions 2.6 mSv, per year (10). Thus, the variation of the natural radiation exposure in Germany is higher than the additional radiation exposure from the X-ray method for age assessment. Furthermore, the increased risk through the X-ray examinations for age assessment is in the range of other daily risks, such as participation in road traffic (10). Therefore, X-ray exposure for age assessment should not be assumed to be outside the range of normal health hazards.

Table 2. Effective radiation doses of X-rays used for age assessment (10, e19, e20).

| X-ray examination | Effective dose (mSv) |

|---|---|

| Hand X-ray | 0.0001 |

| Orthopantomogram | 0.026 |

| Computed tomograpy of medial clavicular epiphysis | 0.4 |

Age assessment methodology

The scientific basis of forensic age assessment in adolescents and young adults is the predetermined temporal progression of defined developmental stages of various characteristics that are identical for all people, such as physical development, skeletal maturation, and dental development. For age assessment, reference studies are used in which these defined developmental stages have been correlated with both the sex and the known age of the examined persons from a reference population.

If there is a legal requirement for X-ray examinations without medical indication, the AGFAD recommends combining physical examination, an X-ray of the hand, and dental examination with a panoramic radiograph of the jaw region. If hand skeletal development is complete, an additional X-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan of the clavicles should be taken (2). These methods have been evaluated with numerous reference studies (11– 24).

Medical history and physical examination

The AGFAD recommended examination procedure begins by taking the medical history, with questions about illnesses and medications that could have influenced growth. A subsequent physical examination records anthropometric data, such as height, weight, and body type, as well as externally visible sexual maturity characteristics (for boys, genital development, pubic hair, underarm hair, beard growth, and laryngeal prominence; for girls, breast development, pubic hair, and hip shape). The main purpose of this initial medical assessment is to identify or rule out growth and developmental disorders. Inference of the chronological age from the biological age (based on skeletal and dental ages) can only be assumed for people with no conspicuous findings.

Pre-existing illnesses can lead to a developmental delay and thus to an underestimation of age, which in legal terms has no adverse consequences for the person concerned. However, it is critical to avoid overestimating age due to disorders that accelerate development. Such disorders are infrequent, but include especially endocrine disorders, which can affect not only adult height and sexual maturation, but also the skeletal maturation.

Endocrine disorders that lead to accelerated skeletal maturity include:

Precocious puberty

Adrenogenital syndrome

Hyperthyroidism.

Physical examinations should therefore take into account symptoms of hormonal development acceleration, such as gigantism, acromegaly, dwarfism, virilization in girls, dissociated virilism in boys, goiter, or exophthalmos (25).

No age assessment can be made in about 1% of cases, due to abnormalities in either the medical history or the physical examination (26). Most often, evidence of hyperthyroidism is found, which may then require further diagnostic evaluation (26).

X-ray examination of the hand

Radiography of the hand forms the second pillar of forensic age estimation. Criteria for evaluating hand radiograms are size and form of the individual bone elements and the ossification status of the epiphyseal plates. The radiograph is then either compared with standard radiographs of the relevant age and sex (atlas method) (e1– e3), or the bone maturity is determined for selected bones (single bone method) (e4, e5). Studies have shown that the single bone method, which is more time consuming, does not increase prediction accuracy. The atlas methods by Greulich and Pyle or Thiemann et al. are therefore considered appropriate for forensic age estimation (27). The ossification rate in the relevant age groups depends primarily on a person’s socio-economic status (28, 29). Applying the relevant reference studies to individuals of a lower socio-economic status is not legally detrimental for the young person concerned, since it leads to an underestimation of age (28, 29).

X-rays of the hand have a double advantage in the context of age assessment. First, a non-mature skeletal hand indicates with high probability a minority youth. Second, X-ray of the hand serves as an indicator for CT scan of the clavicles, which is associated with a significantly higher radiation exposure.

Dental examination

In the dental examination, the developmental characteristics of eruption and mineralization of the third molars are of particular relevance for age estimation. The assessment of dental eruption distinguishes between the stages of alveolar eruption, gingival eruption, and having reached the occlusal plane (30) (eFigure 1). The latter two stages can be determined by oral visual inspection and do not require an X-ray. The mineralization of third molars is assessed with an orthopantomogram. To evaluate tooth mineralization, the staging by Demirjian et al. (31) (eFigure 2) is the most appropriate, because the stages are defined by changes in shape, independent of speculative estimates of length (32). Since the timing of the eruption and mineralization of third molars is dependent on the young person’s ethnicity, population-specific reference studies are to be used for the assessment report (30, 33).

eFigure 1.

Eruption stages of third molars (stage A: occlusal surface at least partially covered with alveolar bone; stage B: complete resorption of the alveolar bone on occlusal surface; stage C: penetration of the gingiva by at least one dental cusp; stage D: emergence on the occlusal plane)

eFigure 2.

Mineralization stages of the third molars (stage A: calcification of the cusps; stage B: unification of the cusps to an occlusal surface; stage C: incipient formation of the cervical region; stage D: complete formation of the tooth crown; stage E: incipient root bifurcation; stage F: root at least as long as the crown, funnel-shaped root endings; stage G: parallel root canal walls, apical endings still partially open; stage H: complete closure of the root tips)

Examination of the clavicles

Following the hand skeletal development, the assessment of the ossification stage of the medial clavicular epiphysis is a further important assessment tool, as the clavicles are the last bones to ossify in the entire skeleton (34). Numerous studies address the timing of clavicular ossification (reviewed in [35]). Of the currently available imaging methods for determining the ossification stage of the medial clavicular epiphysis, thin-slice CT is the method of choice (35, 36). Clavicle ossification is evaluated according to a 5-stage classification system (21, 37) (eFigure 3). Stages 2 and 3 can each be divided into 3 substages (22) (eFigure 4). Stage 3c indicates a minimum age of 19 years (22, 24, e6, e7), while stage 4 indicates a minimum age of 21 years (21, 24, e8, e9).

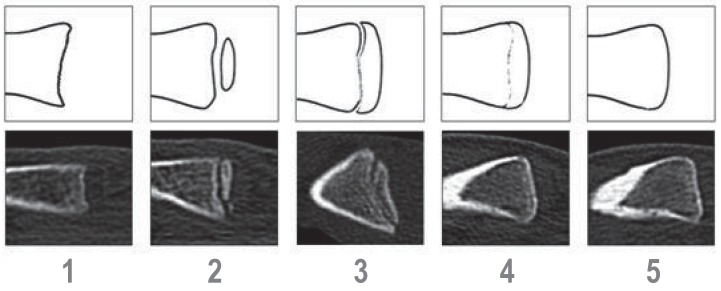

eFigure 3.

Main stages of clavicle ossification (stage 1: non-ossified epiphysis; stage 2: isolated ossified epiphysis; stage 3: partial bony fusion between epiphysis and metaphysis; stage 4: complete bony fusion between epiphysis and metaphysis with definable epiphyseal scar; Stage 5: complete bony fusion between epiphysis and metaphysis without visible epiphyseal scar)

eFigure 4.

Substages of clavicle ossification (stage 2a: the length of ossified epiphysis is maximally one-third the metaphysis width; stage 2b: the epiphysis length is between one-third and two-thirds [maximum] the metaphysis width; stage 2c: the epiphysis length is more than two-thirds the metaphysis width; stage 3a: a maximum of one-third of the epiphyseal plate is ossified; stage 3b: between one-third and two-thirds [maximum] of the epiphyseal plate is ossified; stage 3c: more than two-thirds of the epiphyseal plate is ossified)

Final age assessment

The coordinating expert consolidates the results of a physical examination, X-ray of the hand, dental examination, and, where appropriate, radiological evaluation of the clavicles to reach a final age assessment. The age-relevant variations resulting from the application of the reference studies for the examined person, due for instance to differences in ethnicity, socio-economic status, and possibly due to accelerated development or developmental disorders, have to be discussed in the report. This report should also include any effects that these parameters might have on the estimated age, and if possible, a quantitative assessment of any such effect should be given (2). Differences in age estimations by the different diagnostic tools can be due to a possible endocrine disorder, as dental development is far less affected than the skeletal maturation by such disorders (38). Such a case would require further diagnostic clarification. The procedures for an age assessment report with a legal basis for X-ray examination is shown in Box 2.

Box 2. Course of a forensic age assessment with legal basis for X-ray examinations.

Medical history and physical examination to assess the physical development and to rule out development-related illnesses and medications

X-ray examination of the hand as well as dental examination with panoramic radiograph of the jaw region

Additional thin-slice CT of the medial clavicular epiphysis—only indicated if hand skeletal development is complete

Consolidation of all findings for a final age assessment by a coordinating expert

Procedures without legal basis for X-ray examination

For age estimates without a legal basis for X-ray examinations, AGFAD recommends carrying out a physical examination that takes into account anthropometric data, signs of sexual maturity, potential age-related developmental disorders, and a dental examination including the recording of dentition status (2). Radiological findings of the teeth, the hand skeleton, or any other radiological features of individual maturation may only be used in this legal circumstance if identity-secure reports with a known date of origin are already available.

The confidence level of such age assessments can be expected to increase if non-X-ray–based imaging methods are used. Initial studies on sonographic assessment of ossification of various skeletal structures are available (reviewed in [39]). Since the objective documentation of sonographic studies for subsequent evaluation by a second expert is problematic, the staging for age estimation should be performed independently and a consensus reached by two experts with experience in skeletal sonography (39). A further non–X-ray imaging technique to be considered is magnetic resonance imaging. Likewise, initial studies are available also for this method (for instance [40, e10–e17]).

Significance of forensic age assessment

Depending on the issue to be addressed in the evaluation, the age assessment report should indicate the most likely age and/or the minimum age of the young person examined and comment on the plausibility of the reported age.

If at least one of the studied developmental characteristics (physical development, skeletal maturity, dental development) is not mature, the most likely age of the assessed person can be reported. This is determined based on the combined individual findings and a critical discussion of the specific case. If the most likely age is above the legally relevant age threshold, it is probable that the age limit has been exceeded. As there is currently no reference study in which all relevant age characteristics have been collected simultaneously, it is not yet possible to calculate the statistical spread of the combined age assessments. The report should assure that assessment variations and statistical spread of age-related parameters are addressed beneficially for the affected person to give them the legal benefit of the doubt.

In the case that the legally relevant age limit is surpassed with the highest standard of proof (“with probability bordering on certainty”), the minimum-age concept is applied. The minimum age is derived from the age minimum of the reference study for the determined characteristic value; this is the age of the youngest person in the reference population who had the ascertained characteristic value. If several characteristics were examined, the highest established minimum age shall prevail. The application of the minimum-age concept ensures that the forensic age of the assessed person is never overestimated but instead is almost always less than the actual age. If the determined minimum age lies over the legally relevant age limit, that age has been surpassed with probability bordering on certainty. If the determined minimum age lies over the age provided by the young person being examined, the given age can be virtually ruled out. If the given age is over the determined minimum age, the given age mentioned is compatible with the reported findings. Figure 1 shows the age assessment as described in a case study.

Figure 1.

X-ray findings in a possible minor (age <18.0 years) with a disputed age, and age assessment parameters. The male person examined was from Somalia and claimed to be 17.5 years old. Medical history and physical examination showed no evidence of developmental disorders.

a) The ossification (Oss.) of the hand skeleton (HS) was complete.

b) The mineralization (Miner.) of the third molars (M3) was complete.

c) The ossification (Oss.) of the medial clavicular epiphyses (MCE) was not complete. Both sides were classified as ossification stage 3a, according to Kellinghaus et al. (22).

d) The minimum ages corresponding to the determined developmental stages were 16.1 years old, 17.3 years old, and 16.4 years old (20, 23, 24). The highest minimum age (17.3 years) determines the minimum age of the person examined. The most likely age of the person being examined, according to the relevant median age of stage 3a ossification of the medial clavicles, is 19.5 years old, and the maximum age is 22.3 years (24). Since the minimum age of the examined person is below 18.0 years, a minority status seems possible. Finally, as the minimum age diagnosed falls below the age specified by the person being examined, the assessment evidence is compatible with the age indicated by the person examined

Summary

Forensic age assessments are requested by authorities and courts. Medical experts called on for this are obligated to carry out the assessment; an unfounded refusal can lead to a monetary fine against the commissioned expert. Expert opinions for forensic age assessment, like other expert opinions, ensure a well-functioning legal state, the lack of which is in fact a reason why many people are fleeing their home countries. The expert report must include clear statements on the age assessment reliability in order to allow the decision-making body (authority, court) to consider any doubt such that it leads to the more favorable legal outcome for the affected people.

KEY MESSAGES.

Forensic age assessment is carried out by medical experts on behalf of courts or authorities, to allow age-dependent legal procedures to be correctly carried out for undocumented young people.

The methodology used for forensic age assessment depends on whether or not a legal basis for X-ray examinations without medical indication is present.

The confidence level of age estimates without a legal basis for X-ray examinations is likely to be increased by the use of non–X-ray imaging methods.

Age assessment reports should indicate variations and spread of age-related parameters.

The minimum age concept allows statements about whether an age is under or over the legally relevant limits to be made with the highest standard of proof.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Veronica A. Raker, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Geserick G, Schmeling A. Übersicht zum gegenwärtigen Stand der Altersschätzung Lebender im deutsch-sprachigen Raum. In: Oehmichen M, Geserick G, editors. Osteologische Identifikation und Altersschätzung. Lübeck: Schmidt-Römhild; 2001. pp. 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Forensische Altersdiagnostik. (AGFAD) http://agfad.uni-muenster.de/agfad_start.html. (last accessed on 18 October 2015)

- 3.Schmidt S, Knüfermann R, Tsokos M, Schmeling A. Forensische Altersdiagnostik bei Lebenden am Institut für Rechtsmedizin der Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin: Analyse der im Zeitraum 2001 bis 2007 erstatteten Gutachten. Arch Kriminol. 2009;224:168–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abgeordnetenhaus Berlin. Drucksache 17/16645. pardok.parlament-berlin.de/starweb/adis/citat/VT/17/SchrAnfr/s17- 16645pdf. (last accessed on 18 October 2015)

- 5.Parzeller M. Juristische Aspekte der forensischen Altersdiagnostik. Rechtsprechung-Update 2010-2014. Rechtsmedizin. 2015;25:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowotny T, Eisenberg W, Mohnike K. Strittiges Alter - strittige Altersdiagnostik. Dtsch Aerztebl. 2014;111:A 786–A 788. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudolf E. Entschließungen Deutscher Ärztetage über die forensische Altersdiagnostik. Rechtsmedizin. 2014;24:459–466. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dettmeyer R. Zur Altersfeststellung in behördlichen Verfahren - Anmerkungen zu Entschließungen des Deutschen Ärztetages. Rechtsmedizin. 2010;20:120–121. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmeling A, Geserick G, Tsokos M, Dettmeyer R, Rudolf E, Püschel K. Aktuelle Diskussionen zur Altersdiagnostik bei unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. Rechtsmedizin. 2014;24:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meier N, Schmeling A, Loose R, Vieth V. Altersdiagnostik und Strahlenexposition. Rechtsmedizin. 2015;25:30–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahl B, Schwarze CW. Aktualisierung der Dentitionstabelle von I Schour und M Massler von 1941. Fortschr Kieferorthop. 1988;49:432–443. doi: 10.1007/BF02341233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olze A, Schmeling A, Rieger K, Kalb G, Geserick G. Untersuchungen zum zeitlichen Verlauf der Weisheitszahnmineralisation bei einer deutschen Population. Rechtsmedizin. 2003;13:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olze A, Taniguchi M, Schmeling A, et al. Studies on the chronology of third molar mineralization in a Japanese population. Legal Med. 2004;6:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olze A, van Niekerk P, Schmidt S, et al. Studies on the progress of third molar mineralization in a Black African population. Homo. 2006;57:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jchb.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmeling A, Baumann U, Schmidt S, Wernecke KD, Reisinger W. Reference data for the Thiemann-Nitz method of assessing skeletal age for the purpose of forensic age estimation. Int J Legal Med. 2006;120:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00414-005-0002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olze A, van Niekerk P, Schulz R, Schmeling A. Studies on the chronological course of wisdom tooth eruption in a black African population. J Forensic Sci. 2007;52:1161–1163. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olze A, Ishikawa T, Zhu BL, et al. Studies of the chronological course of wisdom tooth eruption in a Japanese population. Forensic Sci Int. 2008;174:203–206. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2007.04.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olze A, Peschke C, Schulz R, Schmeling A. Studies of the chronological course of wisdom tooth eruption in a German population. J Forensic Legal Med. 2008;15:426–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knell B, Ruhstaller P, Prieels F, Schmeling A. Dental age diagnostics by means of radiographical evaluation of the growth stages of lower wisdom teeth. Int J Legal Med. 2009;123:465–469. doi: 10.1007/s00414-009-0330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tisè M, Mazzarini L, Fabrizzi G, Ferrante L, Giorgetti R, Tagliabracci A. Applicability of Greulich and Pyle method for age assessment in forensic practice on an Italian sample. Int J Legal Med. 2011;125:411–416. doi: 10.1007/s00414-010-0541-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kellinghaus M, Schulz R, Vieth V, Schmidt S, Schmeling A. Forensic age estimation in living subjects based on the ossification status of the medial clavicular epiphysis as revealed by thin-slice multidetector computed tomography. Int J Legal Med. 2010;124:149–154. doi: 10.1007/s00414-009-0398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kellinghaus M, Schulz R, Vieth V, Schmidt S, Pfeiffer H, Schmeling A. Enhanced possibilities to make statements on the ossification status of the medial clavicular epiphysis using an amplified staging scheme in evaluating thin-slice CT scans. Int J Legal Med. 2010;124:321–325. doi: 10.1007/s00414-010-0448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olze A, van Niekerk P, Schulz R, Ribbecke S, Schmeling A. The influence of impaction on the rate of third molar mineralisation in black Africans. Int J Legal Med. 2012;126:869–874. doi: 10.1007/s00414-012-0753-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wittschieber D, Schulz R, Vieth V, et al. The value of sub-stages and thin slices for the assessment of the medial clavicular epiphysis: a prospective multi-center CT study. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2014;10:163–169. doi: 10.1007/s12024-013-9511-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmeling A. Habilitationsschrift. Berlin: Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin; 2004. Forensische Altersdiagnostik bei Lebenden im Strafverfahren. edoc.hu-berlin.de/habilitationen/schmeling-andreas-2004-03-18/PDF/Schmeling.pdf (last accessed on 18 October 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudolf E, Kramer J, Gebauer A, et al. Standardized medical age assessment of refugees with questionable minority claim—a summary of 591 case studies. Int J Legal Med. 2015;129:595–602. doi: 10.1007/s00414-014-1122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt S, Nitz I, Ribbecke S, Schulz R, Pfeiffer H, Schmeling A. Skeletal age determination of the hand: a comparison of methods. Int J Legal Med. 2013;127:691–698. doi: 10.1007/s00414-013-0845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmeling A, Reisinger W, Loreck D, Vendura K, Markus W, Geserick G. Effects of ethnicity on skeletal maturation: consequences for forensic age estimations. Int J Legal Med. 2000;113:253–258. doi: 10.1007/s004149900102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmeling A, Schulz R, Danner B, Rösing FW. The impact of economic progress and modernization in medicine on the ossification of hand and wrist. Int J Legal Med. 2006;120:121–126. doi: 10.1007/s00414-005-0007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olze A, van Niekerk P, Ishikawa T, et al. Comparative study on the effect of ethnicity on wisdom tooth eruption. Int J Legal Med. 2007;121:445–448. doi: 10.1007/s00414-007-0171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Demirjian A, Goldstein H, Tanner JM. A new system of dental age assessment. Hum Biol. 1973;45:211–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olze A, Bilang D, Schmidt S, Wernecke KD, Geserick G, Schmeling A. Validation of common classification systems for assessing the mineralization of third molars. Int J Legal Med. 2005;119:22–26. doi: 10.1007/s00414-004-0489-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olze A, Schmeling A, Taniguchi M, et al. Forensic age estimation in living subjects: the ethnic factor in wisdom tooth mineralization. Int J Legal Med. 2004;118:170–173. doi: 10.1007/s00414-004-0434-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheuer L, Black S. Developmental juvenile osteology. San Diego: Academic Press. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmeling A, Schmidt S, Schulz R, Wittschieber D, Rudolf E. Studienlage zum zeitlichen Verlauf der Schlüsselbeinossifikation. Rechtsmedizin. 2014;24:467–474. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittschieber D, Ottow C, Vieth V, et al. Projection radiography of the clavicle: still recommendable for forensic age diagnostics in living individuals? Int J Legal Med. 2015;129:187–193. doi: 10.1007/s00414-014-1067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmeling A, Schulz R, Reisinger W, Mühler M, Wernecke KD, Geserick G. Studies on the time frame for ossification of the medial clavicular epiphyseal cartilage in conventional radiography. Int J Legal Med. 2004;118:5–8. doi: 10.1007/s00414-003-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleischer-Peters A. Handskelettanalyse und ihre klinische Bedeutung. Fortschr Kieferorthop. 1976;37:375–385. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulz R, Schmidt S, Pfeiffer H, Schmeling A. Sonographische Untersuchungen verschiedener Skelettregionen. Forensische Altersdiagnostik bei lebenden Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen. Rechtsmedizin. 2014;24:480–484. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dvorak J, George J, Junge A, Hodler J. Age determination by magnetic resonance imaging of the wrist in adolescent male football players. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:45–52. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.031021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic atlas of skeletal development of the hand and wrist. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 1959 [Google Scholar]

- e2.Gilsanz V, Ratib O. Hand bone age. A digital atlas of skeletal maturity. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- e3.Thiemann HH, Nitz I, Schmeling A. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme; 2006. Röntgenatlas der normalen Hand im Kindesalter. [Google Scholar]

- e4.Tanner JM, Healy MJR, Goldstein H, Cameron N. London: W.B. Saunders; 2001. Assessment of skeletal maturity and prediction of adult height (TW3 method) [Google Scholar]

- e5.Roche AF, Chumlea WC, Thissen D. Assessing the skeletal maturity of the hand-wrist: Fels method. Springfield: C.C. Thomas. 1988 doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1310010206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Wang YH, Wei H, Ying CL, Wan L, Zhu GY. The staging method of sternal end of clavicle epiphyseal growth by thin layer CT scan and imaging reconstruction. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;29:168–171. 179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Ekizoglu O, Hocaoglu E, Inci E, Can IO, Aksoy S, Sayin I. Estimation of forensic age using substages of ossification of the medial clavicle in living individuals. Int J Legal Med. 2015;129:1259–1264. doi: 10.1007/s00414-015-1234-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Ekizoglu O, Hocaoglu E, Inci E, et al. Forensic age estimation by the Schmeling method: computed tomography analysis of the medial clavicular epiphysis. Int J Legal Med. 2015;129:203–210. doi: 10.1007/s00414-014-1121-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Franklin D, Flavel A. CT evaluation of timing for ossification of the medial clavicular epiphysis in a contemporary Western Australian population. Int J Legal Med. 2015;129:583–594. doi: 10.1007/s00414-014-1116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Jopp E, Schröder I, Maas R, Adam G, Püschel K. Proximale Tibiaepiphyse im Magnetresonanztomogramm. Neue Möglichkeit zur Altersbestimmung bei Lebenden? Rechtsmedizin. 2010;20:464–468. [Google Scholar]

- e11.Hillewig E, De Tobel J, Cuche O, Vandemaele P, Piette M, Verstraete K. Magnetic resonance imaging of the medial extremity of the clavicle in forensic bone age determination: a new four-minute approach. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:757–767. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1978-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Dedouit F, Auriol J, Rousseau H, Rougé D, Crubézy E, Telmon N. Age assessment by magnetic resonance imaging of the knee: a preliminary study. Forensic Sci Int. 2012;217(232):e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Krämer JA, Schmidt S, Jürgens KU, Lentschig M, Schmeling A, Vieth V. Forensic age estimation in living individuals using 30. T MRI of the distal femur. Int J Legal Med. 2014;128:509–514. doi: 10.1007/s00414-014-0967-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Vieth V, Schulz R, Brinkmeier P, Dvorak J, Schmeling A. Age estimation in U-20 football players using 30. tesla MRI of the clavicle. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;241:118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Wittschieber D, Vieth V, Timme M, Dvorak J, Schmeling A. Magnetic resonance imaging of the iliac crest: age estimation in under-20 soccer players. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2014;10:198–202. doi: 10.1007/s12024-014-9548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Baumann P, Widek T, Merkens H, et al. Dental age estimation of living persons: Comparison of MRI with OPG. Forensic Sci Int. 2015;253:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Guo Y, Olze A, Ottow C, et al. Dental age estimation in living individuals using 30. T MRI of lower third molars. Int J Legal Med. 2015;129:1265–1270. doi: 10.1007/s00414-015-1238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Parzeller M. Rechtliche Aspekte der forensischen Altersdiagnostik. Rechtsmedizin. 2011;21:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- e19.Okkalides D, Futakis M. Patient effective dose resulting from radiographic examinations. Br J Radiol. 1994;67:564–572. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-67-798-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Frederiksen NL, Benson BW, Sokolowski TW. Effective dose and risk assessment from film tomography used for dental implant diagnostics. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1994;23:123–127. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.23.3.7835511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]