Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the frequency of hastening death discussions, describe current parental endorsement of hastening death and intensive symptom management, and explore whether child’s pain influences these views among a sample of parents whose child died of cancer.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Two tertiary-care US pediatric institutions.

Participants

141 parents of children who died of cancer (response rate 64%).

Outcome measures

Proportion of parents who (1)considered or (2)discussed hastening death during the end-of-life, and (3)who endorsed hastening death or (4)intensive symptom management in vignettes portraying children with end-stage cancer.

Results

a total of 19 out of 141, (13%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 8%–19%) parents considered requesting hastening death for their child, and 9% (95%CI, 4%–14%) discussed hastening death; consideration of hastening death tended to increase with increasing child suffering from pain. In retrospect, 34% (95%CI, 26%–42%) of parents reported they would have considered hastening their child’s death had the child been in uncontrollable pain, while 15% or less would consider hastening death for non-physical suffering. In response to vignettes, 50% (95%CI, 42%–58%) of parents endorsed hastening death while 94% (95%CI, 90%–98%) endorsed intensive pain management. Parents were more likely to endorse hastening death if the vignette involved a child in pain as compared to in coma (odds ratio, 1.4; 95%CI, 1.1–1.8).

Conclusions

More than 10% of parents considered hastening their child’s death and this was more likely if the child was in pain. Attention to pain and suffering, and education about intensive symptom management may mitigate consideration of hastening death among parents of children with cancer.

Keywords: Children, Cancer, Palliative Care, Terminal Care, Hospice, Attitude to Death, Death, Hastened death, Euthanasia, Physician assisted suicide

Introduction

While providing care for patients with advanced life-threatening illnesses, clinicians may face inquiries about hastening death (HD).1, 2 Among adults with advanced illness HD discussions occur about 10 to 20% of the time, with serious requests taking place only in 2 to 10% of the cases.3–5 With two US states now having legalized physician assisted suicide6, these discussions may become more frequent. Attitudes towards HD in non-infant children with life-threatening conditions have seldom been described. The existing reports come from the Netherlands7, 8, where euthanasia is legal for infants and children older than 12 years, and although they provide relevant ethical, legal, and policy considerations, their clinical applicability outside of the Netherlands is limited.

The Institute of Medicine has recommended that HD requests be “fully explored”9, stemming from the understanding that, typically, substantial suffering, which can be uncovered and alleviated, underlies such requests.10–12 Specifically, hopelessness and psychosocial distress have been associated with HD requests in adult patients.3–5, 13, 14. On the other hand, actual physical suffering has not been conclusively linked to desire for HD.14 Instead, imaginary pain, such as pain in others or the prospect of one’s own pain, has been associated with lay persons’ endorsement of HD vignettes. 15, 16 Similarly, patients who feared uncontrolled symptoms, but not those who had them, were more likely to request HD in Oregon.17 These findings become particularly interesting when thinking about what may motivate a parent’s consideration of HD.

In order to better understand considerations of HD among parents of children with cancer, and to examine the role of child suffering in prompting HD conversations, we asked bereaved parents whether they considered or requested hastening of death during their child’s illness, and whether different circumstances would have motivated such a consideration. Using clinical vignettes of a child with end-stage cancer, we further examined parental endorsement of hastening death and their endorsement of proportionally intensive symptom management. Finally, we explored whether child’s pain was associated with past and current hastening death views.

Methods

Methods of this retrospective cross-sectional survey have been previously described.18–21 From 1997 to 2001, we interviewed parents and physicians of children who died of cancer between 1990 and 1999 and were cared for at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Children’s Hospital, Boston (DFCI/CHB), or Children’s Hospitals and Clinics, St. Paul/Minneapolis (CHC). The protocol was approved by both institutional review boards (IRB). Permission to contact the family was obtained from the child’s primary oncologist. Parents were eligible if they spoke English, resided in North America, and their child had died at least one year before contact. Eligible families received a letter of invitation containing either a postage-paid “opt-out” (DFCI) or “opt-in” (CHC) postcard in agreement with each site’s IRB requirements. We interviewed one parent per family, designated by the family. Three trained interviewers and three of the investigators carried out all interviews.

Primary physicians denied us permission to contact 19 families, leaving a total of 244 eligible parents. Of 222 parents whom we reached, 141 completed the surveys (response rate 64%). Responders and non-responders did not differ with regard to child’s age at death or diagnosis. Interviews were primarily telephone-administered; however, 35 were done face-to-face based on the parent’s request. Interviews were conducted a median of 3.3 years after the child’s death (range 1.1–10.8 years).

Parental survey

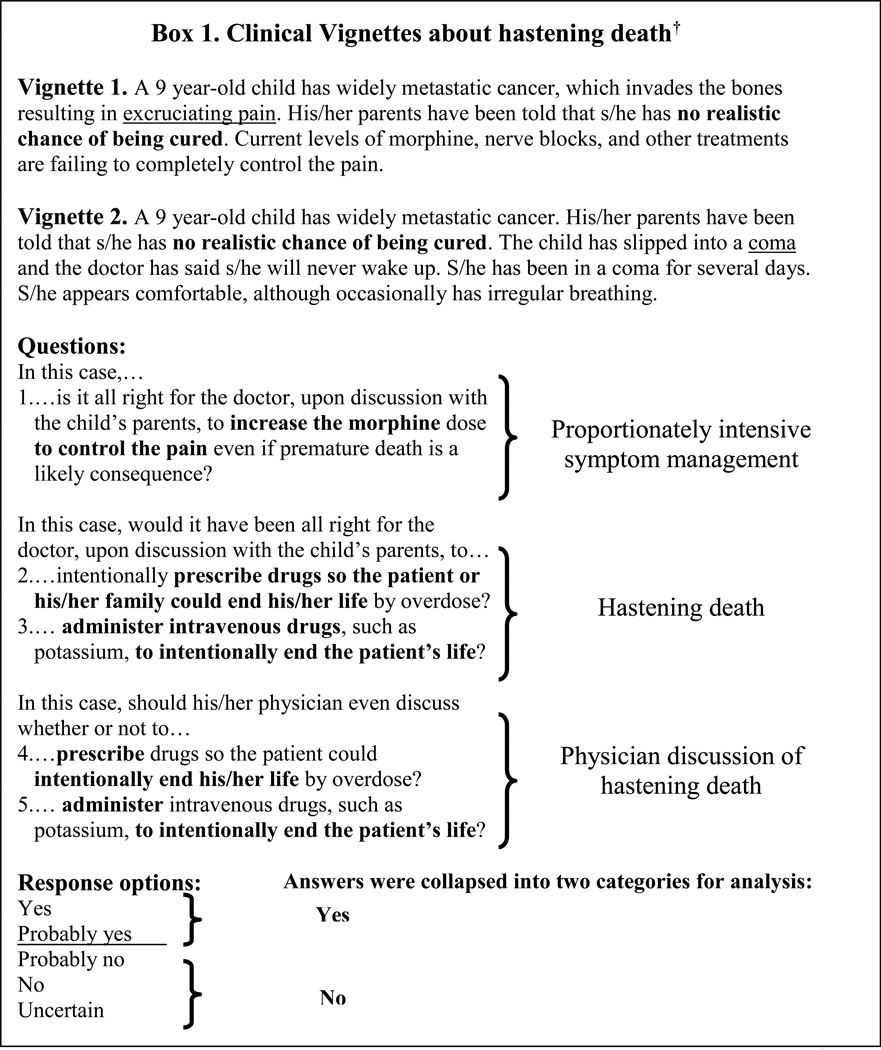

The parental survey was a 390-item semi-structured questionnaire with most items developed de novo, following guidelines by Streiner and Norman22 and using focus groups of parents and caregivers.19 Items evaluated in this report include whether parents ever considered HD (“During your child’s end-of-life care period, did you or a family member ever considered asking someone on the care team to give him/her or give you or the family member medications to intentionally end his/her life?”), held discussions about HD (“When your child was receiving end-of-life care, did you or a family member ever discuss intentionally ending his/her life?”), asked someone to proceed with HD (“Did you or a family member ask someone on your child’s care team to give him/her medications or to give you or the family member medications to intentionally end his/her life?”), or actually intentionally ended their child’s life (“Did a member of your child’s care team give your child medications or did you or a family member give him/her medications to intentionally end his/her life?”). We also asked parents whether specific considerations (e.g. uncontrollable pain, to control his/her death, child’s life was too limited) would have affected their desire for HD for their child (question and response options are shown in text and tables). Finally, bereaved parents’ current views about HD were assessed using two clinical vignettes (Figure 1) adapted from similar ones developed for adult patients.4 Both vignettes described a 9-year-old child with widely metastatic cancer and no realistic chance of cure, each with a different end-of-life circumstance: uncontrollable pain (vignette 1), and irreversible coma (vignette 2). For each clinical scenario, we asked parents whether they would endorse intensive symptom management, death hastened by family or physician action, and if it would be all right for physicians to raise these topics with families.

Figure 1.

Clinical vignettes about hastening death. Adapted from Emanuel and colleagues.4

Parents were also asked about their child’s symptoms, quality of life, care characteristics, and their own experience during the child’s last month of life. Location of death, and socio-demographic and family characteristics were also collected.

Medical Record Review

Child’s age at death, gender, diagnosis, and cause of death (i.e., disease progression vs. treatment-related) were abstracted from medical records.

Statistical methods

The analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.1 for Windows. Due to the sensitive nature of the study items, we created a de-identified database for this analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize parents’ actual experiences with HD during their child’s EOL course and their current views about HD. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95%CIs) for rates were calculated using normal approximation to the binomial distribution.

Relevant family characteristics associated with consideration of HD during end-of-life were explored by performing univariate anlysis using Fisher’s exact test. Univariate associations of family characteristics with endorsement of HD in vignettes were tested using logistic regression models (PROC GENMOD, see below). Family characteristics examined were: race, marital status, education, annual income, health insurance, religion, religiousness and having had a prior loss. Annual income, originally a 7 category variable, was dichotomized at US$75,000 based on data distribution; this cut point corresponds roughly with the 80th percentile of the US annual household income for the years the question referred to.23

Consideration of hastening death during the child’s end-of-life and child’s pain suffering

Suffering from pain during the last month of life was an ordinal, five category variable (not at all, a little, some, a lot, or a great deal of suffering). To test increasing consideration of HD across the five pain categories we performed the Cochran-Armitage test for trends. To adjust for relevant family characteristics we ran a logistic regression model including family characteristics with a p-value of <0.25 in univariate analyses. A p<0.05 was required for variable retention. Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Endorsement of hastening death in vignettes and pain

To explore whether child’s pain was associated with bereaved parents’ endorsement of HD we used a multivariate modeling approach. This analysis is a complete case approach based on the 140 parents who responded to the vignettes.

Endorsement of HD was the main dependent variable. Answers to each HD question (i.e. Family HD - pain vignette, Physician HD - pain vignette, Family HD - coma vignette, and Physician HD - coma vignette) were collapsed into two categories (yes/ no, see Box 1) and treated as separate observations. Thus, the unit of analysis was the answer to each HD question rather than each subject’s response.

To account for the non-independence of responses given by the same parent (i.e., up to four responses per parent), we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) using PROC GENMOD in SAS to fit two-level logistic regression models, where the first level represented the answer to each HD question and the second level, the parent. The main independent variable was type of vignette (pain vs. coma). Family characteristics with a p< 0.25 in univarate analyses were entered into the model and retained if p<0.05. Results are reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the study population. Parents were predominantly white, married, and college-educated; a substantial minority was Catholic, although most were not very religious.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children who died of cancer and their parents

| N=141 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study Site (State) | ||

| Massachusetts | 102 (72) | |

| Minnesota | 39 (28) | |

| Child characteristics | ||

| Child gender, Female | 66 (47) | |

| Age at death in yrs, mean (SD) | 10.2 (6.6) | |

| Type of cancer | ||

| Hematological malignancy | 70 (50) | |

| Solid or Brain Tumor | 70 (50) | |

| Cause of death | ||

| Disease Progression | 110 (79) | |

| Treatment-related | 29 (21) | |

| Parent and family characteristicsa | ||

| Respondent gender, Female | 117 (83) | |

| Parental age at child’s death in yrs, mean (SD) | 39.3 (7.6) | |

| Married at the time of the child’s death | 121 (86) | |

| White non-Hispanic | 131 (93) | |

| College graduate or more | 75 (53) | |

| Annual Income ≥U$S 75,000b (n=139) | 42 (30) | |

| Private insurance | 126 (89) | |

| Catholic | 65 (46) | |

| Not very religiousc (n=140) | 89 (64) | |

| Family experienced prior loss | 110 (78) | |

| Prior death associated with high suffering (n=134) | 41 (31) | |

Denominator is indicated when it differs from total sample

Income was collapsed at US$75,000, representing the 80th percentile of the US annual household income for the survey years (see Methods)

Corresponds to response options “somewhat” and “not at all” religious (vs. very religious)

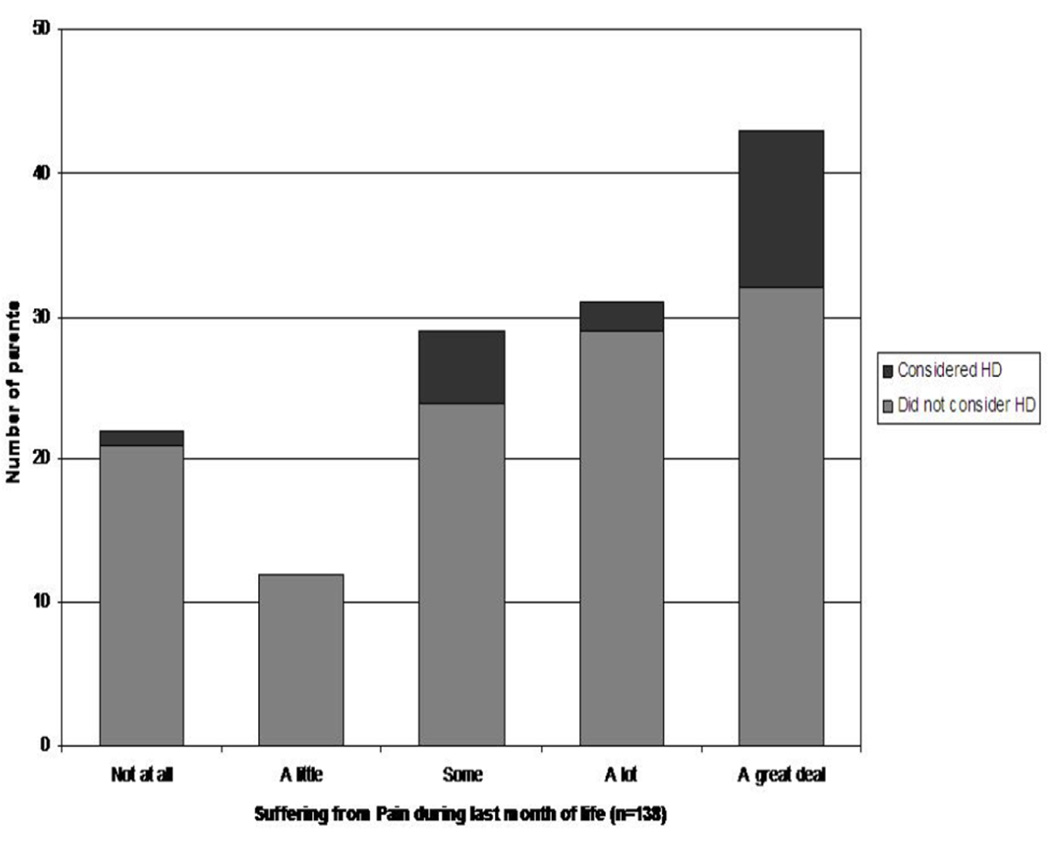

Reported experience with hastening death

Nineteen of 141 parents (13%, 95%CI 8–19%) reported that they had considered asking about HD, and 13 parents (9%, 95%CI 4–14%) reported having discussed intentionally ending their child’s life. Five parents (4%, 95%CI 0.5–7%) reported having explicitly asked a clinician for medications to end the child’s life, and three parents (2%, 95%CI 0–3%) reported that their child’s life was intentionally ended with medication. In all three cases, the medication used was morphine. Parents who reported an annual income larger than US$75,000 were more likely to consider hastening their child’s death, whereas Catholic parents were less likely to do so (Table 2). Figure 1 shows the proportion of parents who considered HD across the 5 categories of suffering from pain during the child’s last month of life. Consideration of HD increased with increasing suffering from pain. The proportion of parents considering HD increased from 5% when the child had no pain suffering, to 26% when the child suffered a great deal from pain (Cochran-Armitage two sided exact trend test p-value=0.018). These results remained stable after adjusting by high income and being catholic (OR 1.7, 95%CI 1.1–2.8, p=0.025).

Table 2.

Family characteristics associated with parent’s consideration of hastening death during the child’s EOL period. Univariate analysis.a

| Family characteristicsb | YES (N=19) % |

NO (N=122) % |

|---|---|---|

| White non-Hispanic | 95 | 93 |

| Married | 95 | 84 |

| College graduate or more | 63 | 52 |

| Annual Income ≥U$S 75,000c (n=139) | 53 | 27* |

| Private insurance | 100 | 88 |

| Catholic | 16 | 51** |

| Not very religiousd (n=140) | 84 | 60 |

| Family experienced prior loss | 84 | 77 |

p-values correspond to Fisher’s Exact Test

Denominator is indicated when it differs from total sample

Income was collapsed at US$75,000, representing the 80th percentile of the US annual household income for the survey years (see Methods)

Corresponds to response options “somewhat” and “not at all” religious (vs. very religious)

p-value< 0.05

p-value≤ 0.01

Current views about hastening death

Circumstances in which parents would have considered hastening death

In retrospect, 36% (95%CI 28–44%) of parents reported that they would have considered HD for their child under certain circumstances (Table 3). Most commonly, parents would have considered HD if their child had been in uncontrollable pain (34%, 95%CI 26–42%). A minority of parents (15% or less) would have considered HD for non-physical suffering, such as not wanting child to live this way, a release from life, or to control the death. Almost no parents would have considered HD for circumstances not directly related to the child’s experience.

Table 3.

Circumstances under which parents of children who died of cancer would have considered discussing hastening death

| N=136a % (95%CI) |

|

|---|---|

| Would have considered hastening death under certain circumstancesb | 36 (28–44) |

| Circumstances: | |

| Uncontrollable pain (n=134) | 34 (26–42) |

| Child or parent didn’t want child to live this way (n=133) | 15 (9–22) |

| Death was a release from your child’s life (n=133) | 15 (9–21) |

| To control his/her death (n=134) | 12 (7–18) |

| Life seemed meaningless and purposeless (n=133) | 7 (2–11) |

| Child’s life was too limited (n=134) | 6 (2–10) |

| Didn’t want your family to see your child suffer (n=134) | 1 (0–2) |

| Costs of medical care (n=134) | 1c (0–2) |

| Caring for child was a burden on the family (n=134) | 0 (0) |

Results are reported as percentages and their 95%CI.

The actual question was: “Given what you know now, can you imagine (other) circumstances in which you might have wanted to ask a member of your child’s care team to give him/her medications or give you or a family member medications to intentionally end his/her life?” Followed by, “May I ask about several circumstances in which you might have done this? (Specify all)”.

answered “maybe”

Endorsement of hastening death in vignettes

When responding to the vignettes, 94% of parents (95%CI 90–98%) endorsed proportionately intensive symptom management for a terminally ill child with uncontrolled excruciating pain, while only 54% (95%CI 45–62%) did so for a child in irreversible coma. Seventy parents (50%, 95%CI 42–58%) endorsed HD in at least one vignette. Among the 19 parents who reported considering HD during their child’s EOL course, 16 (84%) also endorsed HD in vignettes. Fifty-nine percent of the parents (95%CI 50–67%) would agree with physicians discussing intentionally ending a child’s life for a terminally ill child in pain or coma.

Among the family variables analyzed, being Non-Hispanic White and not very religious were associated with endorsement of hastening death in vignettes (Table 4). Parents were 40% more likely to endorse hastening death for a child with intractable pain than for a terminally ill child in coma (46% vs. 36%; OR 1.4, 95%CI 1.1–1.8). Results did not change after adjusting by race and religiousness.

Table 4.

Family characteristics associated with parent’s endorsement of hastening death in vignettes. Univariate analysis.a

| Family characteristicsb | YES (N=70) % |

NO (N=70) % |

|---|---|---|

| White non-Hispanic | 97 | 89** |

| Married | 87 | 49 |

| College graduate or more | 53 | 53 |

| Annual Income ≥U$S 75,000c (n=139) | 33 | 29 |

| Private insurance | 91 | 87 |

| Catholic | 40 | 53 |

| Not very religiousd (n=140) | 77 | 51** |

| Family experienced prior loss | 77 | 79 |

Each parent answered 4 hastening death questions. Percents correspond to the proportion of parents who endorsed at least one hastening death question. p-values correspond to univariate logistic regression models where answers to each HD question were considered separate observations, i.e. the unit of analysis was each HD question. Correlation among responses from the same subject was accounted for using clustered analysis where level 1 represented the answer to each hastening death question and level 2 each parent.

Denominator is indicated when it differs from total sample

Income was collapsed at US$75,000, representing the 80th percentile of the US annual household income for the survey years (see Methods)

Corresponds to response options “somewhat” and “not at all” religious (vs. very religious)

p-value≤ 0.01

Discussion

Family perspectives about HD in children have not been previously described. Rather than taking sides in the HD debate our intention was to examine this topic from a clinical point of view. Our study reveals that consideration of and discussions about HD in children with cancer do, in fact, occur. We also found that the child’s experience of pain impacts on HD considerations. Specifically, unrelieved pain was associated with parents’ past considerations of HD and current views, both regarding their own child and in vignettes. Importantly, parents overwhelmingly endorsed intensive symptom management for pain relief, an alternative approach to relieving uncontrollable pain in children.

More than 1 of every 8 parents reported considering HD and one in ten reported having had a HD discussion, a comparable proportion to what has been described for adults with terminal cancer.4 Furthermore, 1 of every 3 parents would have considered HD retrospectively for their own child had the circumstances been different, and 1 of 2 endorsed HD in vignettes, which is also similar to the US public endorsement of HD for adults.1 These findings suggest that the proportion of parents who would consider HD may fluctuate depending on the child’s clinical condition; clinicians caring for a child with advanced cancer should thus be prepared to hold discussions related to HD considerations.

Our findings offer some initial hypotheses regarding underlying factors leading to HD requests. First, suffering may play a role in the family’s request. A thorough exploration of the child’s suffering from pain as well as other sources of suffering may be important. In addition, not surprisingly, family characteristics are related to parental consideration of HD. Race, religiousness, and income, along with education have already been identified as characteristics associated with endorsement of HD by the general public.24, 25 Existing expert recommendations suggest that being sensitive and respectful of these values, and having a listening and nonjudgmental attitude may foster an open conversation that increases clinician’s understanding of the family’s motivations and in turn relieves child and family’s distress.26 The same experts’ guideline highlights the importance of physicians’ self-awareness about their own opinion about HD. In fact, physicians from the Netherlands and Oregon, where HD is legal, report that these conversations are highly challenging. Finding an equilibrium between their own position and their willingness to relief patient’s suffering does not come easily.27, 28

If physical suffering is identified, our results suggest that parents are willing to have an open discussion about existing options including effective and legal alternatives such as proportionately intensive symptom management and palliative sedation. Desires for hastened death may represent an “exit plan”29, to be used if no other alternatives are recognized. Although we did not explicitly explore this in our sample, the circumstances under which parents would have considered HD for their own child suggest that parents may think about HD as a means to end intolerable pain. In these cases, developing alternative plans may ease parent’s views about HD. Proportionately intensive symptom management involves, in the case of pain, a proportionate increase in analgesic doses in order to control the pain while accepting a higher risk of sedation or even respiratory depression.30 Palliative sedation (or sedation to unconsciousness) is used in the context of imminent death and may be indicated when all intensive symptom management options fail to provide adequate relief. Palliative sedation involves administering analgesic and sedative agents until unconsciousness is reached and may be accompanied by the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments to allow death to happen.31

When talking to parents about these alternatives, it may be worth explaining that appropriate use of intensive symptom management rarely causes an actual hastening of death. Several studies indicate that both caregivers32, 33 and physicians34, 35 tend to confuse the unintended adverse effects of intensive symptom management with the intentional hastening of death. In our own sample, the three families reporting intentionally hastening their child’s death described doing so by using morphine, which raises the question about whether they had misinterpreted the physicians’ intentions. In fact, evidence indicates that opioids can be used safely at the end of life and that their effect on survival, if any, is negligible.36–39

The study has some limitations. It could be argued that parental endorsement of HD in hypothetical vignettes may not fully represent their views for a child of their own. However, in this sample, most parents who considered HD during their child’s terminal phase also endorsed HD in vignettes. In addition, when asked about circumstances when they would have considered HD for their own child, parents’ answers were very similar to those depicted in the vignettes. Specifically, uncontrolled pain was the top factor identified by parents using both survey strategies. For these reasons, we believe vignettes emerge as a valid and acceptable proxy for current thoughts about HD.

Given our small sample, prevalence estimates may be prone to error. However, in light of the sensitive nature of the topic and social desirability bias, we hypothesize that HD discussions may have been underreported and therefore our results, if anything, would underestimate their frequency. Estimates of actual HD on the other hand may be overestimated given parent’s apparent confusion between HD and intensive symptom management. In future studies of determinants of desiring HD it would also be helpful to include prospective longitudinal data, especially since HD perspectives have been shown to fluctuate over time.40

We have only focused on pain as a trigger for HD consideration or discussion and this is clearly a limited view, since other types of child or parental suffering may be similarly associated with HD. Although further research is needed to explore these associations, we chose pain because despite the advances in the palliative care field this is still a prevalent and inadequately treated symptom.41

Another limitation is related to the age of the data, which may be of concern for two reasons, potential for recall bias, and secular trends that influence views about HD. We feel that given the salience of the event, recall bias about having considered HD is not likely a significant concern. Regarding changing secular trends, since the data were collected, two states in the US now accept physician assisted suicide as legal6 and at the same time, palliative strategies are much more integrated into care.41 It is possible that these changes might impact the prevalence of considering HD although no recent studies have examined this; on the other hand, the effects of pain on HD views should not be affected by secular trends. Finally, our results are difficult to extrapolate beyond cancer. Other pediatric life-limiting conditions involve varying degrees of disability, burden, and time course, all of which may yield very different patterns of HD perspectives among parents.

Implications/Conclusions

Our study results suggest that more than 1 of every 8 parents report considering HD during their child’s illness and they tended to do so if their child was in pain. In the context of an HD discussion, identifying sources of suffering and clearly explaining effective and legal options including proportionately intensive symptom management may ease parents’ considerations of hastening their child’s death.

Figure 2.

Proportion of parents who considered hastening their child’ death across increasing levels of child’ suffering from pain (n=138; Cochran-Armitage trend test p=0.018). HD: hastening death.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for sharing their stories. We would like to thank Caron Moore, RN, MSW for her contribution with data collection.

Funding

Authors’ work was independent of funders. V Dussel was the recipient of a fellowship from the Agency for Health Research and Quality (T32HP10018). J Watterson-Schaeffer was partially supported by the Pine Tree Apple Tennis Classic Oncology Research Fund. J Wolfe was the recipient of Grant No. NCI 5 K07 CA096746 from the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- HD

hastening death

- EOL

end-of-life

Footnotes

Authors Contributions

JW led the study and is its guarantor. JW, VD, SJJ, and JCW are responsible for study conception and design. JW, JMH, and JWS conducted data collection, VD carried out the statistical analysis. VD, SJJ, and JW carried out analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the paper. All authors revised and approved the manuscript. JW and VD had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest and Financial Disclosure Statement

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and no financial disclosures to declare.

References

- 1.Emanuel EJ. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a review of the empirical data from the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Jan 28;162(2):142–152. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickinson GE, Clark D, Winslow M, Marples R. US physicians' attitudes concerning euthanasia and physician-assisted death: A systematic literature review. Mortality. 2005;10(1):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA. 2000 Dec 13;284(22):2907–2911. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Emanuel LL. Attitudes and desires related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among terminally ill patients and their caregivers. JAMA. 2000 Nov 15;284(19):2460–2468. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodin G, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, et al. The desire for hastened death in patients with metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007 Jun;33(6):661–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinbrook R. Physician-assisted death--from Oregon to Washington State. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 11;359(24):2513–2515. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0809394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vrakking AM, van der Heide A, Arts WF, et al. Medical end-of-life decisions for children in the Netherlands. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005 Sep;159(9):802–809. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.9.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pousset G, Bilsen J, De Wilde J, Deliens L, Mortier F. Attitudes of Flemish secondary school students towards euthanasia and other end-of-life decisions in minors. Child Care Health Dev. 2009 Jan 9; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00933.x. [EPub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field MJ, Cassel CK. Approaching death: improving care at the end of life. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1997. Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Care at the End of Life. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroepfer TA. Critical events in the dying process: the potential for physical and psychosocial suffering. J Palliat Med. 2007 Feb;10(1):136–147. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starks H, Pearlman RA, Hsu C, Back AL, Gordon JR, Bharucha AJ. Why now? Timing and circumstances of hastened deaths. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005 Sep;30(3):215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, McPherson CJ, et al. Desire for euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide in palliative cancer care. Health Psychol. 2007 May;26(3):314–323. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.3.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Lee ML, van der Bom JG, Swarte NB, Heintz AP, de Graeff A, van den Bout J. Euthanasia and depression: a prospective cohort study among terminally ill cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Sep 20;23(27):6607–6612. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson PL, Kristjanson LJ, Ashby M, et al. Desire for hastened death in patients with advanced disease and the evidence base of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2006 Oct;20(7):693–701. doi: 10.1177/0269216306071799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Daniels ER, Clarridge BR. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: attitudes and experiences of oncology patients, oncologists, and the public. Lancet. 1996;347(9018):1805–1810. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genuis SJ, Genuis SK, Chang WC. Public attitudes toward the right to die. CMAJ. 1994 Mar 1;150(5):701–708. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganzini L, Goy ER, Dobscha SK. Oregonians' reasons for requesting physician aid in dying. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 9;169(5):489–492. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Dec 20;23(36):9155–9161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mack JW, Joffe S, Hilden JM, et al. Parents' Views of Cancer-Directed Therapy for Children With No Realistic Chance for Cure. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Sep 8; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. Second. New York: Oxford Medical Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Census Bureau. [Accessed July 31, 2009];Historical Income Tables - Households. Income Limits for Each Fifth and Top 5 Percent of Households. All Races: 1967 to 2007. 2007 http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/histinc/h01AR.html.

- 24.Domino G. Community attitudes toward physician assisted suicide. Omega (Westport) 2002;46(3):199–214. doi: 10.2190/chl6-y148-vbbh-22nb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strate J, Kiska T, Zalman M. Who favors legalizing physician-assisted suicide? The vote on Michigan's Proposal B. Politics Life Sci. 2001 Sep;20(2):155–163. doi: 10.1017/s073093840000544x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson PL, Schofield P, Kelly B, et al. Responding to desire to die statements from patients with advanced disease: recommendations for health professionals. Palliat Med. 2006 Oct;20(7):703–710. doi: 10.1177/0269216306071814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Georges JJ, The AM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Wal G. Dealing with requests for euthanasia: a qualitative study investigating the experience of general practitioners. J Med Ethics. 2008 Mar;34(3):150–155. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.020909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganzini L, Nelson HD, Lee MA, Kraemer DF, Schmidt TA, Delorit MA. Oregon physicians' attitudes about and experiences with end-of-life care since passage of the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. JAMA. 2001 May 9;285(18):2363–2369. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nissim R, Gagliese L, Rodin G. The desire for hastened death in individuals with advanced cancer: a longitudinal qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2009 Jul;69(2):165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quill TE. Dying and decision making--evolution of end-of-life options. N Engl J Med. 2004 May 13;350(20):2029–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quill TE, Lee BC, Nunn S. Palliative treatments of last resort: choosing the least harmful alternative. University of Pennsylvania Center for Bioethics Assisted Suicide Consensus Panel. Ann Intern Med. 2000 Mar 21;132(6):488–493. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-6-200003210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morita T, Ikenaga M, Adachi I, et al. Concerns of family members of patients receiving palliative sedation therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2004 Dec;12(12):885–889. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morita T, Ikenaga M, Adachi I, et al. Family experience with palliative sedation therapy for terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004 Dec;28(6):557–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilsen J, Norup M, Deliens L, et al. Drugs used to alleviate symptoms with life shortening as a possible side effect: end-of-life care in six European countries. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 Feb;31(2):111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Heide A, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G, Kollee LA, de Leeuw R. Using potentially life-shortening drugs in neonates and infants. Crit Care Med. 2000 Jul;28(7):2595–2599. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorns A, Sykes N. Opioid use in last week of life and implications for end-of-life decision-making. Lancet. 2000 Jul 29;356(9227):398–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Good PD, Ravenscroft PJ, Cavenagh J. Effects of opioids and sedatives on survival in an Australian inpatient palliative care population. Intern Med J. 2005 Sep;35(9):512–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2005.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morita T, Chinone Y, Ikenaga M, et al. Efficacy and safety of palliative sedation therapy: a multicenter, prospective, observational study conducted on specialized palliative care units in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005 Oct;30(4):320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Claessens P, Menten J, Schotsmans P, Broeckaert B. Palliative sedation: a review of the research literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008 Sep;36(3):310–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johansen S, Holen JC, Kaasa S, Loge HJ, Materstvedt LJ. Attitudes towards, and wishes for, euthanasia in advanced cancer patients at a palliative medicine unit. Palliat Med. 2005 Sep;19(6):454–460. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1048oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008 Apr 1;26(10):1717–1723. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]