Abstract

Previous studies have identified healthcare practices that may place undue pressure on related donors (RDs) of hematopoietic cell products, and an increase in serious adverse events associated with morbidities in this population. As a result, specific requirements to safeguard RD health have been introduced to FACT-JACIE Standards, but the impact of accreditation on RD care has not previously been evaluated. A survey of transplant program directors of EBMT member centers was conducted by the Donor Health and Safety Working Committee of the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) to test the hypothesis that RD care in FACT-JACIE accredited centers is more closely aligned with international consensus donor care recommendations than RD care delivered in centers without accreditation. Responses were received from 39% of 304 centers. Our results show that practice in accredited centers was much closer to recommended standards as compared to non-accredited centers. Specifically, a higher percentage of accredited centers use eligibility criteria to assess RDs (93% versus 78%; P=0.02) and a lower percentage have a single physician simultaneously responsible for a RD and their recipient (14% versus 35%; P=0.008). In contrast, where regulatory standards do not exist, both accredited and non-accredited centers fell short of accepted best practice. These results raise concerns that despite improvements in care, current practice can place undue pressure on donors, and may increase the risk of donation-associated adverse events. We recommend measures to address these issues through enhancement of regulatory standards as well as national initiatives to standardize RD care.

Keywords: related donor, JACIE, accreditation, hematopoietic cell donation

Introduction

Current data suggest that the incidence of donation associated adverse events, including death, is higher in related donors (RDs) than UDs.1 This is particularly true of RDs who do not meet unrelated donor (UD) suitability criteria, yet relatives donating hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) are frequently permitted to proceed with morbidities for which an UD would be deferred.2-4 This inequality in practice occurs due to several key differences between the care of UDs and RDs, including a lack of regulatory guidance in the RD setting, and logistical or financial barriers.

In the UD field, the recognized need to both ensure the safety of stem cell products for recipients internationally, and to protect volunteer donors, led to foundation of the World Marrow Donor Association (WMDA) in 1988 as a global organization providing regulation and guidance for HPC donor registries. WMDA Standards5 attempt to minimize coercion of UDs through the requirement that the medical team providing their care will have no involvement in the care of their recipient, and by preserving anonymity throughout the donation process. To safeguard UD health, donors are automatically deferred if they do not meet clear suitability criteria against which they are assessed at three stages: recruitment, verification typing and a formal donor medical assessment.6 Information about donation is provided at each of these stages, which are often months or years apart in time, ensuring longstanding motivation to proceed with donation.

The situation for related donors (RDs) is more complex. They lack the benefit of anonymity and, as a result of historical care pathways, almost invariably donate at the same transplant center treating their relative. The intimacy of their relationship with the transplant recipient may yield feelings that translate to an internal pressure to donate, including the desire to help their sick relative, a sense of duty or even guilt.7,8 RDs are also vulnerable to experiencing additional pressure to donate from external sources, such as their relatives, or members of the healthcare team caring for their potential recipient. Furthermore, RD tend to be older than UDs, and are more likely to have morbidities, which they may underplay in view of their motivation to donate.

Previous investigations have raised concerns that practice in Europe does not sufficiently protect RDs from experiencing undue pressure. This issue was first addressed in a study conducted by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Nurses Group/Late Effects working party.9 Sixty-three nurses, delegates at the 2005 EBMT annual meeting, completed questionnaires regarding the counseling, consent and follow up of RDs at their centers. Findings suggested large variation in donor counseling practices; only 25% of responding nurses indicated that RDs were consented by a physician who was not involved in the care of their recipient Furthermore, they showed that in in 11% of centers the donor's HLA results would be first disclosed to their recipient breaching confidentiality and potentially pressuring the donor to proceed. A survey of US transplant center directors in 200710 reported a potential conflict of interest in >70% of centers, where the same physician caring for the donor had either simultaneous responsibility for, or might be involved in the care of, the recipient. In 2012, an analysis of the care of 500 related donors in Italy 11 further highlighted issues with overlapping donor/recipient care and showed that only 26% of donors underwent thorough screening according to Italian Bone Marrow Donor Registry standards.

A few recent consensus statements have offered guidance around RD care. In 2010, a WMDA working group published recommendations for family donor care12 focusing on appropriate counseling and assessment prior to HLA typing, avoidance of conflict of interest by care providers and RD follow-up. In 2013, a Worldwide Network of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (WBMT) consensus paper advocated standardized assessment of donor outcome with a minimum data set.13 The Joint Accreditation Committee ISCT and EBMT (JACIE)/Foundation for the Accreditation of Cellular Therapy (FACT) has also introduced specific standards to address some of these issues, including donor evaluation criteria, a donor follow up policy and the requirement that “Allogeneic donor suitability should be evaluated by a physician who is not the physician of the recipient.”14 In many European countries, however, accreditation is not mandatory for centers assessing RDs, and no studies to date have investigated the impact of accreditation on practice patterns in RD care.

We hypothesized that adult RD practice remains heterogeneous, and is more likely to mirror UD care in accredited than in non-accredited transplant centers. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a survey of EBMT transplant center directors, designed to assess areas of care addressed by the 2005 survey, and additional areas where clear UD standards exist, but which are not yet embedded in regulatory guidance for RDs.

Materials and methods

A 38-item survey was developed to examine related donor care practice (see Supplementary Appendix). Questions were designed to determine center adherence to 5th JACIE Standards,14 to WMDA recommendations for RD care15 and to WBMT donor follow up recommendations13. The survey was administered as an internet-based questionnaire via a secure hyperlink (surveymonkey.com) from August to November 2014. Program directors of all US transplant centers reporting data to CIBMTR and all EBMT allogeneic transplant member centers received an email invitation to participate, with a request to forward the survey to the physician responsible for RD care. UK centers, where a very similar survey had recently been conducted, were excluded. Entry into a drawing for a free CIBMTR/ASBMT Tandem Annual Meeting registration was offered as an incentive to increase the response rate. All procedures were reviewed by the NMDP Institutional Review Board, This study was also approved by the Donor Outcomes Committee of the EBMT, whose mailing list was used to contact EBMT centers.

Due to differences in practice, the results from CIBMTR and EBMT centers were analyzed separately. The EBMT center data is presented in this manuscript.

In view of known differences between adult and pediatric RD care (due to the requirement for a donor advocate in the pediatric setting by EU Directive 2004/23/EC), this study focused purely on the care of adult RDs. The survey invitation specified that the study referred to the care of adult related stem cell donors only, and the survey terminated if respondents answered ‘no' to the first question “Does your center perform allogeneic HPC transplants from adult (>18 years old) related donors?”.

Following the initial invitation, non-responders received three further email reminders. Where greater than one response was received from a center, the most complete was used for analysis. Four responses were excluded from analyses because they stated they did not perform allogeneic transplants using related donors >18 years of age. Data were not available to determine the number of non-responding centers performing purely pediatric transplants that would therefore have been ineligible for the study.

Centers were grouped by size in the analysis defined as the number of first allografts performed per year. These data were collected from EBMT activity survey.16 Centers were also grouped according to their geographical location including Eastern Europe; Northern; Southern Europe; Western Europe and Non-European Nations. To minimize ‘drop-outs' from the survey, the set-up allowed participants to skip questions, however results were only analyzed and presented for questions that >80% of responding centers had completed. Statistics were performed using SPSS software (version 22.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Relationships between categorical center characteristics and response rate or adherence to standards were examined using Chi squared or Fisher's exact test where appropriate. All variables found to be significant in univariate analyses were included in a multivariable stepwise logistic regression analysis.

Results

Response rate

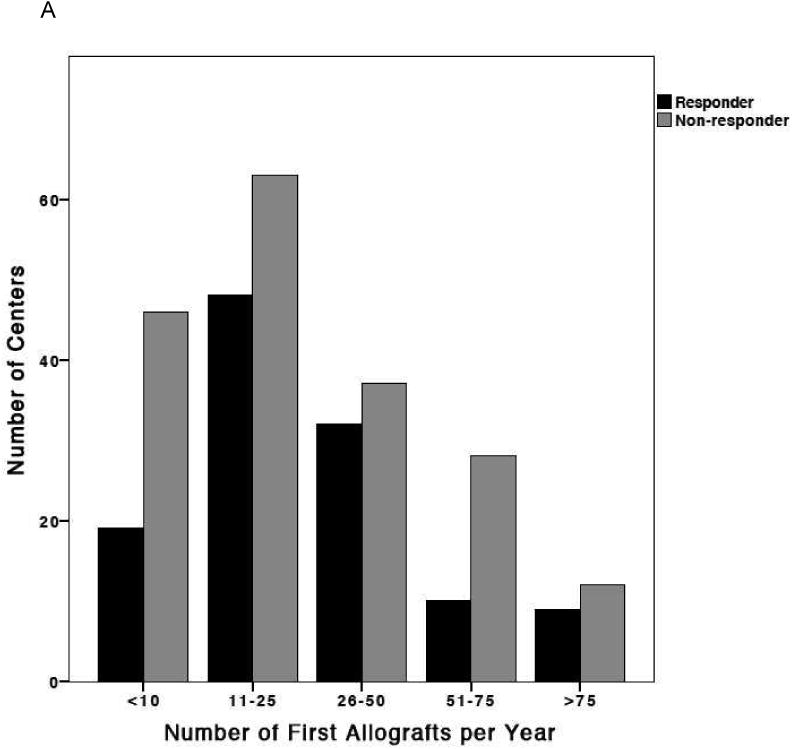

Excluding duplicates, 118 eligible responses were received from 304 centers, a response rate of 39%, with a significantly higher response rate in FACT-JACIE accredited compared to non-accredited centers (52% versus 33%; P=0.001). Overall 59/118 (50%) responding centers had FACT-JACIE accreditation. As shown in Figure 1, no consistent pattern in response rate by center size was observed. The median number of first allografts per year in responding centers was 23 (range 1-172). As shown in Figure 1B, no significant difference in response rate was observed between geographical regions (P=0.151).

Figure 1. Characteristics of responding and non-responding centers.

(A) Distribution of transplant center volumes at responding and non-responding centers. (B) Distribution of responding and non-responding transplant centers by geographic region: Eastern Europe; Northern Europe; Southern Europe; Western Europe and Non-European Nations

The impact of FACT-JACIE accreditation on practice

We found multiple significant practice differences between accredited and non-accredited transplant centers (shown in Table 1). Across key indicators, practice in accredited centers was more likely to conform to international consensus recommendations than that in non-accredited centers. As expected, this difference was particularly evident in those areas of care addressed by current FACT-JACIE Standards, where accredited centers were far more likely to conform to the recommendation. Accredited centers were significantly more likely to have a policy for RD care (98% versus 83%; P=0.004), to use defined eligibility criteria to assess RDs (93% versus 78%; P=0.02), and to have a process for credentialing physicians performing BM harvests (86% versus 63%; P=0.008).

Table 1. Responses regarding the care of donors at the point of HLA typing, health care providers of donor care, and donor care policies in accredited and non-accredited EBMT transplant centers.

| JACIE accredited | Non-accredited | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Healthcare provider making initial contact prior to HLA-typing | |||

| Transplant physician | 23 (40%) | 24 (41%) | |

| Other Physician | 15 (26%) | 17 (29) | |

| Transplant Specialist Nurse | 15 (26%) | 14 (24%) | 0.70 |

| Other nurse | 2(3%) | 0 | |

| Non-clinical Admin | 3 (5%) | 3 (5%) | |

|

| |||

| Information supplied to donors pre HLA typing | |||

| Verbal only | 26 (4%) | 34 (60%) | |

| Local written information | 31(53%) | 20 (35%) | 0.073 |

| National written information | 1(2%) | 3(5%) | |

|

| |||

| RD heath assessment pre-HLA typing | |||

| By written health questionnaire | 12 (21%) | 8 (14%) | |

| Health questionnaire over phone | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 0.49 |

| Verbal discussion open ended questions | 18 (32%) | 23 (40%) | |

| No assessment | 24 (42%) | 25 (44%) | |

|

| |||

| Willingness to donate is verified pre-HLA typing | 40 (69%) | 46 (79%) | 0.20 |

|

| |||

| Individual to whom donor HLA results are first disclosed | |||

| Donor | 22 (38%) | 9 (16%) | 0.007 |

| Recipient | 10 (17%) | 15 (26%) | |

| Referring physician | 23 (40%) | 27 (47%) | |

| No consistent practice | 3 (5%) | 6 (11%) | |

|

| |||

| Background of the provider with ultimate responsibility for RD clearance | |||

| Internist/GP | 1 (2%) | 0 | |

| Non-transplant hematologist | 29 (50%) | 18 (31%) | 0.036 |

| Transplant physician | 26 (45%) | 40 (69%) | |

| Other | 2 (3%) | 0 | |

|

| |||

| Role of the physician providing donor clearance in the recipient's care | |||

| Affiliated with transplant program with simultaneous responsibility for the recipient | 8 (14%) | 20 (35%) | |

| Affiliated with the transplant program and may be involved in the care of the recipient | 20 (34%) | 17 (30%) | 0.044 |

| Affiliated with the transplant program but not involved in recipient's care | 19 (33%) | 15 (26%) | |

| Not involved in the transplant program or the recipient's care | 11 (19%) | 5 (9%) | |

|

| |||

| Existence of a written policy for RD care | 58 (98%) | 49 (83%) | 0.004 |

|

| |||

| Written eligibility criteria exist for acceptance of RDs | 53 (93%) | 45 (78%) | 0.02 |

|

| |||

| Source of eligibility criteria | |||

| Locally written | 30 (53%) | 21 (36%) | |

| Based on NMDP criteria | 16 (28%) | 19 (33%) | |

| Based on WMDA criteria | 27 (48%) | 12 (21%) | |

|

| |||

| A health history questionnaire forms part of the assessment at donor medical | 52 (91%) | 41 (72%) | 0.008 |

|

| |||

| There is a policy defining the limit for the number of apheresis procedures RDs may undergo for their initial donation | 39 (72%) | 31 (55%) | 0.057 |

|

| |||

| Plerixa for has been used for mobilization of RDs | |||

| Yes | 11 (20%) | 21 (38%) | |

| No | 38 (69%) | 34 (61%) | 0.032 |

| Only in the context of a clinical trial | 6 (11%) | 1 (2%) | |

|

| |||

| BM harvests are performed by: | |||

| Transplant physicians caring for the recipient | 43 (77%) | 41 (87%) | |

| Other transplant physicians or another team | 13 (23%) | 6(13%) | 0.36 |

|

| |||

| There is a process for credentialing physicians performing BM harvests | 48 (86%) | 29 (63%) | 0.008 |

|

| |||

| There is a policy defining the limit for the BM volume aspirated at harvest | 37 (66%) | 30 (65%) | 0.984 |

|

| |||

| Long term (10 year) follow up is performed | 20 (34%) | 8 (14%) | 0.05 |

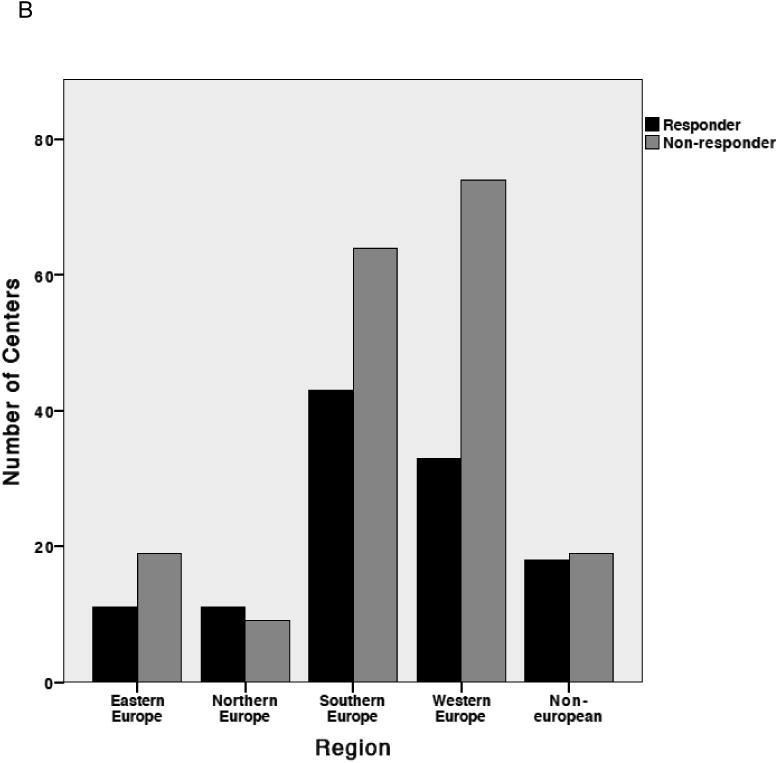

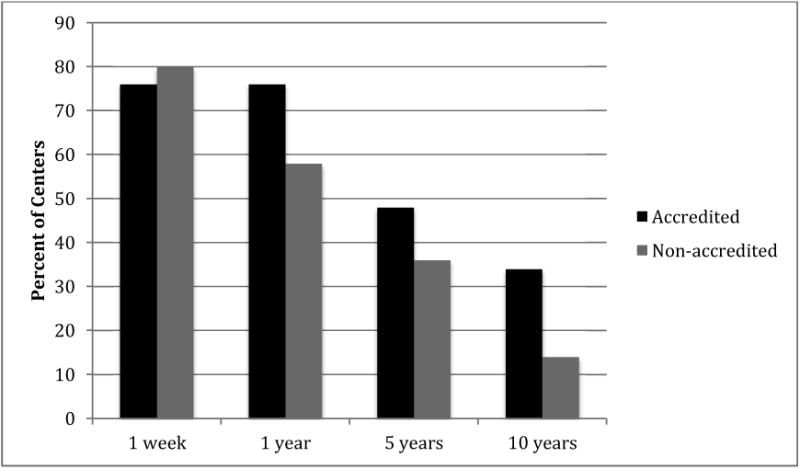

As shown in Figure 2, medical clearance of related donors was undertaken by transplant physicians in 45% of accredited and 69% of non-accredited centers (P=0.036) and overall a quarter of centers failed to comply with the FACT-JACIE requirement that the donor's physician should not be simultaneously responsible for the recipient. This practice of overlapping care occurred more frequently in non-accredited centers (14% accredited, 35% non-accredited; P=0.008).

Figure 2. Effect of accreditation on healthcare providers of donor care.

(A) Background of physicians responsible for donor medical clearance. (B) Involvement of donor's physician in care of the recipient

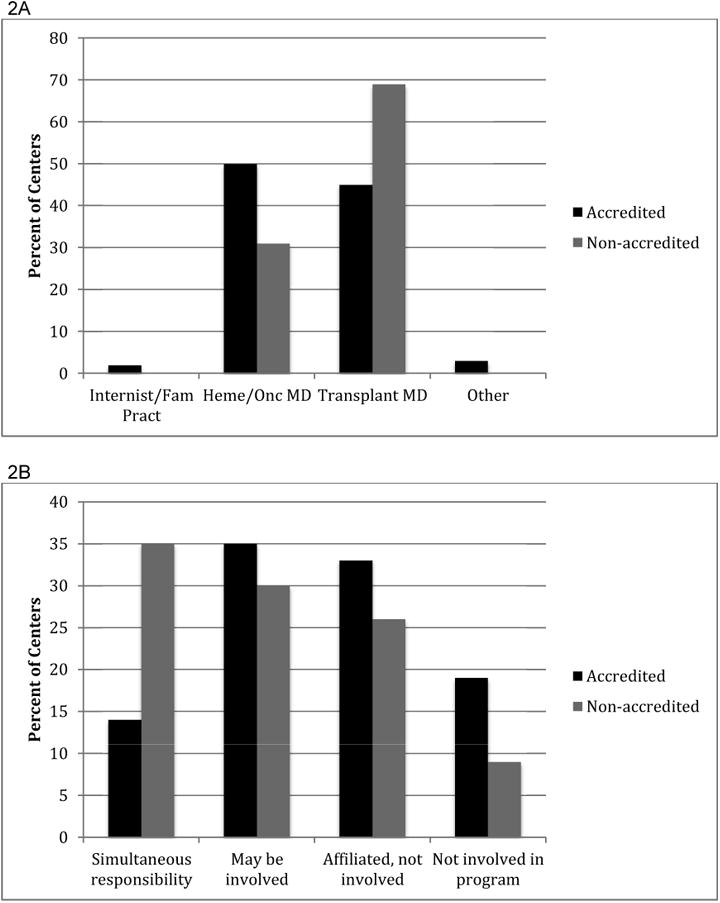

We examined areas of care outside the remit of current (5th) FACT-JACIE Standards, but where international consensus recommendations or standard UD practices offer a benchmark. Here we found that accredited centers more frequently complied with several recommendations, including that they were less likely to first disclose the donor's HLA results to an individual other than the donor themselves (61% versus 86%; P=0.007). We asked whether centers had used plerixafor as a mobilizing agent in related donors, and found that a significantly higher proportion of non-accredited centers had done so (20% accredited versus 38% non-accredited; P=0.032). As shown in Figure 3, 89% of the centers described a follow up program, which continued beyond one-year post donation in over two thirds and up to 10 years in 20% of centers. Although accreditation did not impact the likelihood of providing a follow up program, the accredited centers more frequently adhered to WBMT recommendations for 10-year donor follow up (34% versus 14%; P=0.05).

Figure 3. Effect of accreditation on related donor follow up.

The percent of accredited and non-accredited transplant centers performing related donor follow up at 1 week, 1 year, 5 years and 10 years

We found other areas of practice not addressed by FACT-JACIE Standards, in which both accredited and non-accredited centers did not follow international guidelines. Care prior to HLA typing was markedly inconsistent with recommendations on family donor care management produced by a subgroup of WMDA,15 and to UD norms, with 40% of respondents indicating that no assessment of donor health is made prior to HLA typing and a quarter failing to verify that donors are willing to donate at this point. There was a trend towards accredited centers being more likely to supply donors with written information prior to HLA typing, which occurred in 55% of accredited and 45% of non-accredited centers (P=0.073).

A trend was also observed towards accredited centers being more likely to have a policy defining a limit to the number of apheresis procedures a donor could undergo during their initial donation (72% versus 55%; P=0.057), but no impact was observed on the likelihood of a policy defining BM harvest limits, which existed in 66% of centers. Where details on these harvest limits were given, they were in line with UD policies in nearly all cases.

Centers performing fewer than the median 23 allogeneic HCTs per year were less likely to be accredited than higher volume centers, however, center volume did not significantly impact any practice parameters in multivariate analysis.

Discussion

These results provide unique insights into RD care in EBMT transplant centers, and the impact of FACT-JACIE accreditation in this field. We found better compliance with internationally recognized donor care paradigms in centers with FACT-JACIE accreditation, but crucially also found important practice gaps in all centers irrespective of accreditation.

We were unable to obtain information regarding which centers were purely pediatric, and all EBMT centers were therefore invited to complete the survey. Thus, although the response rate was relatively low at 39%, it is likely that ineligible pediatric centers comprised many of the non-responding centers.

Although our study differed from the earlier survey conducted by the EBMT Nurses Group/Late Effects working party,9 it is nevertheless possible to draw several robust conclusions about progress over the nine years between studies. Firstly, only 25% of respondents in the earlier survey stated that RDs were consented by a physician not involved in recipient care. Although not a direct comparison, we show here that in 75% of centers the physician providing medical clearance of the RD was not routinely responsible for the care of the recipient. Secondly, donor follow up has become more prevalent, with 89% of responding centers now providing a follow up program compared to 60% in 2005. This may in part be attributable to the development of a system for centralized reporting for related donor outcome data by the EBMT donor group, in addition to national regulations mandating follow up in some countries.

Despite this progress, we identified several stages of the RD care pathway where practice continues to put the donor's health and autonomy at risk, and we urge RD care providers to consider the following issues. In >40% of centers no assessment of donor health is made prior to HLA typing, thus a donor's medical issues will not be identified until the formal donor medical assessment, shortly before donation. This practice may lead to donors' purposefully or inadvertently failing to disclose medical issues during the subsequent medical assessment (and in doing so putting themselves – and potentially the recipient - at risk when donating), or being cancelled at the point of donor medical clearance, incurring a potentially critical delay in the recipient's HCT. Furthermore, >70% of centers breach confidentiality by first disclosing the donor's HLA matching status another individual, a practice that potentially places undue pressure the donor to proceed, since he/she cannot then decline to donate without potential repercussions on their relationship with the recipient. Lastly, we hope to see a further reduction in the practice of routine overlap of recipient and donor care following introduction of 6th edition of FACT-JACIE standard where the recommendation for divided responsibility for donor and recipient care in the previous standard's edition has now been changed to a requirement.

Another important finding of this survey is the fact that off-label plerixa for has already been used in related donors by a considerable number of centers. Hence there is an urgent need to register and follow these donors to analyze long-term safety of this and other new drugs to come.

There are compelling reasons to address these issues. Potential related donors are identified by their sick relatives, unlike UDs who are anonymous. It will never be possible to eliminate the pressure to donate; therefore policies to minimize this are crucial. Transplant physicians undertake most aspects of RD care in over 80% of centers, and major changes would be required to have a separate team assume responsibility for RDs. If independent donor care is not feasible, clear policies to avoid conflicts of interest and protect donor health should be implemented, such as mandating a donor advocate be involved in the process. Several issues we identify here could be addressed by simple changes to current procedures without significant cost implications, for example ensuring that HLA matching status is disclosed to the donor first, with permission required before disclosure to another party. Similarly, comprehensive information about the donation process could be provided, and a health assessment completed in advance of HLA typing, possibly over the phone or via email as per successful UD registry practice.

The improvements in donor care that we show have specifically occurred in areas where recent FACT-JACIE standards were introduced, confirming the impact of quality management in driving change. A similar effect of FACT-JACIE accreditation on allogeneic HCT patient care has been recently demonstrated, with substantial stepwise improvements in long and short-term patient outcomes with each step of the process towards accreditation in EBMT transplant centers.17

In some countries, transplant centers (TCs) are obliged to conform to accreditation, but this is not universally the case in Europe, where >50% of TCs are not accredited. We encourage non-accredited centers to adopt regulatory guidance around RD care, but other approaches must also be considered, particularly the creation of evidence based RD care guidelines at a national or international level. The WBMT donor issues committee is developing eligibility guidelines for assessment of related donors who do not meet suitability criteria for UDs, an area in which guidance to safeguard RD health is much needed. UD registries have a wealth of experience in donor care and could also facilitate improvements in the RD field either by sharing donor information resources with TCs, or, in some countries, through national initiatives to improve donor follow up.

The continuing increase in haploidentical transplantation raises several questions for the future of RD care, including whether transplant centers have the provision for performing increasing volumes of time consuming assessments. In addition, most studies to date investigating RD experience and psychological outcomes are based on sibling donors, and the dynamics of, for example, a parent/child relationship are different and require additional consideration.18 This survey focused on determining the current status of adult RD practice in EBMT centers, similar studies investigating pediatric practice are needed. Exploring the perceptions of transplant physicians regarding the barriers to providing optimal care would be helpful to determine how to best realize improvements, which would likely best be driven by further augmentation of FACT-JACIE Standards.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Related donor care in accredited centers is closer to international recommendations

Despite improvements over time, current practice can place undue pressure on donors

In areas lacking regulatory guidance, practice in all centers differs from UD standards

Long term follow up of related donors is becoming more prevalent

Acknowledgments

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-13-1-0039 and N00014-14-1-0028 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from *Actinium Pharmaceuticals; Allos Therapeutics, Inc.; *Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; *Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; *Celgene Corporation; Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; *Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.;*Gentium SpA; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Jeff Gordon Children's Foundation; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac GmbH; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; *Milliman USA, Inc.; *Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; *Remedy Informatics; *Sanofi US; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; St. Baldrick's Foundation; StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stemsoft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; *Tarix Pharmaceuticals; *TerumoBCT; *Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; *THERAKOS, Inc.; University of Minnesota; University of Utah; and *Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Corporate Members

Authorship Contributions: C.A, P.V.O., D.M.K. and B.E.S. designed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; M.N., M.B., P.A., J.Y., B.N.S., M.A.D., J.P.H., B.R.L., G.E.S., M.A.P. and D.L.C. critically revised the paper.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Halter J, Kodera Y, Ispizua AU, et al. Severe events in donors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell donation. Haematologica. 2009;94(1):94–101. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthias C, Ethell ME, Potter MN, Madrigal A, Shaw BE. The impact of improved JACIE standards on the care of related BM and PBSC donors. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2014;50(2):244–247. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiersum-Osselton JC, van Walraven SM, Bank I, et al. Clinical outcomes after peripheral blood stem cell donation by related donors: a Dutch singled center cohort study. Transfusion. 2013;53(1):96–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kodera Y, Yamamoto K, Harada M, et al. PBSC collection from family donors in Japan: a prospective survey. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2013;49(2):195–200. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WMDA. International Standards for Unrelated Hematopoietic Progenitor Cell Donor Registries standards W. International Standards for Unrelated Hematopoietic Progenitor Cell Donor Registries. [Accessed October 9, 2013]; Available at: http://www.worldmarrow.org/fileadmin/Committees/STDC/20140101-STDC-WMDA_Standards.pdf.

- 6.Sacchi N, Costeas P, Hartwell L, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell donor registries: World Marrow Donor Association recommendations for evaluation of donor health. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2008;42(1):9–14. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillay B, Lee SJ, Katona L, et al. The psychosocial impact of haematopoietic SCT on sibling donors. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2012;47(10):1361–1365. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The influence of the donor-recipient relationship on related donor reactions to stem cell donation. 2014;49(6):831–835. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clare S, Mank A, Stone R, et al. Management of related donor care: a European survey. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2010;45(1):97–101. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Donnell PV, Pedersen TL, Confer DL, et al. Practice patterns for evaluation, consent, and care of related donors and recipients at hematopoietic cell transplantation centers in the United States. Blood. 2010;115(24):5097–5101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-262915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coluccia P, Crovetti G, Del Fante C, et al. Screening of related donors and peripheral blood stem cell collection practices at different Italian apheresis centres. Blood Transfus. 2012;10(4):440–447. doi: 10.2450/2012.0140-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Walraven SM, Faveri GND, Axdorph-Nygell UAI, et al. Family donor care management: principles and recommendations. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2010;45(8):1269–1273. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halter JP, van Walraven SM, Worel N, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell donation-standardized assessment of donor outcome data: a consensus statement from the Worldwide Network for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (WBMT) Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2013;48(2):220–225. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joint Accreditation Committee - ISCT & EBMT. International standards for cellular therapy product collection processing and adminstration. [Accessed October 9, 2013]; Available at: http://www.jacie.org.

- 15.van Walraven SM, Nicoloso-de Faveri G, Axdorph-Nygell UAI, et al. Family donor care management: principles and recommendations. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2009;45(8):1269–1273. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passweg J, Baldomero H, Bregni M, et al. Hematopoietic SCT in Europe: data and trends in 2011. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gratwohl A, Brand R, McGrath E, et al. Use of the quality management system “JACIE” and outcome after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2014;99(5):908–915. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.096461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Walraven SM, Ball LM, Koopman HM, et al. Managing a dual role-experiences and coping strategies of parents donating haploidentical G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood stem cells to their children. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;21(2):168–175. doi: 10.1002/pon.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.