Abstract

A previous neurophysiological investigation demonstrated an increase in functional projections of expiratory bulbospinal neurons (EBSNs) in the segment above a chronic lateral thoracic spinal cord lesion that severed their axons. We have now investigated how this plasticity might be manifested in thoracic motoneurons by measuring their respiratory drive and the connections to them from individual EBSNs. In anesthetized cats, simultaneous recordings were made intracellularly from motoneurons in the segment above a left-side chronic (16 wk) lesion of the spinal cord in the rostral part of T8, T9, or T10 and extracellularly from EBSNs in the right caudal medulla, antidromically excited from just above the lesion but not from below. Spike-triggered averaging was used to measure the connections between pairs of EBSNs and motoneurons. Connections were found to have a very similar distribution to normal and were, if anything (nonsignificantly), weaker than normal, being present for 42/158 pairs, vs. 55/154 pairs in controls. The expiratory drive in expiratory motoneurons appeared stronger than in controls but again not significantly so. Thus we conclude that new connections made by the EBSNs following these lesions were made to neurons other than α-motoneurons. However, a previously unidentified form of functional plasticity was seen in that there was a significant increase in the excitation of motoneurons during postinspiration, being manifest either in increased incidence of expiratory decrementing respiratory drive potentials or in an increased amplitude of the postinspiratory depolarizing phase in inspiratory motoneurons. We suggest that this component arose from spinal cord interneurons.

Keywords: spinal cord injury, thoracic motoneurons, respiratory drive, plasticity

most effort in experimental spinal cord injury (SCI) studies has been directed at segments below a spinal lesion, where the general focus has been on the loss of function (notably motor function) that occurs in these lower segments and its restoration. However, segments above the lesion also suffer effects of SCI. In these higher segments, there will be loss of ascending inputs, both from the periphery and from local and propriospinal interneurons, as well as possible changes in modulatory state (Becker and Parker 2015). Descending interneurons (or those with bifurcating axons with both ascending and descending branches; Saywell et al. 2011) that are located within the segments above the injury may also suffer from the effects of axotomy or loss of their targets (Conta and Stelzner 2004; Conta Steencken et al. 2010, 2011). Furthermore, in some instances, especially for human cervical SCI, changes in the neural circuits immediately rostral to the injury may be profoundly important for the degree of upper limb control available to the injured person (Fawcett 2002): any repair strategy that might restore function by the equivalent of one segment might, for instance, add useful hand function to the control of only the proximal limb.

The present study is one of a series into the plasticity that naturally occurs in the segment above a lateral lesion of the thoracic spinal cord, the aim being to investigate the specificity of any new connections formed in these circumstances without the complications inherent either in regeneration across a lesion or in the multisynaptic interneuronal circuits that may be strengthened around a lesion (Arvanian et al. 2006; Bareyre et al. 2004; Courtine et al. 2008; for review, see Filli and Schwab 2015; Flynn et al. 2011). Useful neurons for this purpose are the expiratory bulbospinal neurons (EBSNs), which make direct connections to motoneurons in each thoracic segment (Saywell et al. 2007). One study from this laboratory has already shown that the physiologically assessed projections of these neurons increase in the segment immediately above a lateral lesion that transected their axons (Ford et al. 2000). The experiments described here were devised to measure the specificity of connections that may be involved in these projections, namely the connections to different categories of motoneuron. However, while making these measurements, we noticed that there were some overall changes in the respiratory drive to the motoneurons, which comprise a different aspect of functional plasticity. This paper describes both of these measurements. Preliminary results have appeared (Anissimova et al. 2000, 2001).

METHODS

Animals.

Experiments were conducted according to United Kingdom legislation [Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986] under Project and Personal Licences issued by the United Kingdom Home Office. The data come from 19 adult cats, 17 male, initial weights 2.2–4.5 kg. Control data came from acute experiments on uninjured animals previously described (Saywell et al. 2007).

Spinal lesions.

Anesthesia was induced with ketamine and chlorpromazine (40 and 1 mg/kg, respectively) or with ketamine and acepromazine (36 and 0.12 mg/kg, respectively) intramuscularly (Ketaset, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Southampton, United Kingdom; acepromazine, C-Vet Veterinary Products, Grampian Pharmaceutical) and maintained with ketamine intravenously (transcutaneous catheter in the cephalic vein) as required. The analgesic buprenorphine was administered (0.3 mg sc; Vetergesic) at the end of the surgery and usually also the next day. Heart rate was monitored using an esophageal electrode. Aseptic precautions were taken.

A dorsal midline incision was made, and the paraspinal muscles were retracted from two midthoracic vertebrae. A partial laminectomy was made of the caudal end of the rostral of these two and usually also a small part of the left side at the rostral end of the other so as to allow access to the cord at the rostral part of the caudal underlying segment (T8, T9, or T10: 7, 7, and 5 cats, respectively). The dura was opened, and either a no. 11 or a small optical scalpel blade was used to make a partial hemisection to the left side of the spinal cord, sparing the dorsal columns. It was aimed to make the lesion near or just caudal to the level of the most rostral dorsal root of that segment. This position spared the roots and dorsal root ganglion of the segment above (verified postmortem in all animals). The dura was folded back over the lesioned cord, and the muscles closed in layers, applying Cicatrin (Glaxo Wellcome) antibiotic between layers. The skin was closed with absorbable suture, a spray dressing (OPSITE; Smith & Nephew) was applied, and an antibiotic (amoxicillin, 150 mg im) was administered.

Functional recovery was monitored carefully thereafter, especially for the 1st few days following the operation. Bowel function was restored in most animals by the morning of day 3 (D3), in all by D4, standing on 4 legs mostly by D3, in all by D6, walking using 4 legs mostly by D4, in all by D7, and a near normal gait by all within 3 wk (D0 was the day of the operation). Animals had been specifically selected that were of a friendly disposition to make it easier to be able to identify any distress or requirements for additional analgesia and to monitor the wound status, bowel and bladder functions, and locomotion.

Terminal physiological experiments.

Terminal physiological experiments were carried out between 15 and 18 (mostly 16) wk following the lesion and are as described in more detail in Saywell et al. (2007). Animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (initial dose 37.5 mg/kg ip, then iv as required), maintained under neuromuscular blockade with gallamine triethiodide (subsequent to surgery, repeated doses, 24 mg iv, as required), and artificially ventilated via a tracheal cannula with oxygen-enriched air so as to bring the end-tidal CO2 fraction initially to ∼4%. CO2 was then added to the gas mixture to raise the end-tidal level to a value sufficient to give a brisk respiratory discharge in the midthoracic intercostal nerves (typically 6–7%). A low stroke volume and a high pump rate (53/min) were employed so that events related to the central respiratory drive could be distinguished from those due to movement-related afferent input. Venous and arterial cannulae were inserted.

We aimed to use a (surgically adequate) level of anesthesia in the range light to moderately deep, as described by Kirkwood et al. (1982). Before neuromuscular blockade, a weak withdrawal reflex was elicited by noxious pinch applied to the forepaw but not to the hindpaw. When present, pinch-evoked changes in blood pressure (measured via a femoral arterial cannula) were absent or were small and of short duration. During neuromuscular blockade, anesthesia was assessed by continuous observations of the patterns of the respiratory discharges and blood pressure together with responses, if any, of both of these to a noxious pinch of the forepaw. Only minimal, transient responses (similar to those before neuromuscular blockade) were allowed before supplements (5 mg/kg) of pentobarbitone were administered. The responses to a noxious pinch always provided the formal criteria, but in practice the respiratory pattern, indicated by an external intercostal nerve discharge that was continuously monitored on a loudspeaker from the induction of neuromuscular blockade, always gave a premonitory indication. Any increase from the usual slow respiratory rate typical of barbiturate anesthesia (e.g., Fig. 3) led to such a test being carried out. The animal was supported, prone, by vertebral clamps, a clamp on the iliac crest, and a plate screwed to the skull. The head was somewhat ventroflexed. Rectal temperature was maintained between 37 and 38°C by a thermostatically controlled heating blanket. The bladder was emptied by manual compression at intervals. Systolic blood pressures were above 80 mmHg throughout. At the end of the experiment, the animals were either killed with an overdose of anesthetic or were given a supplement of anesthetic and killed by perfusion for histology (see below).

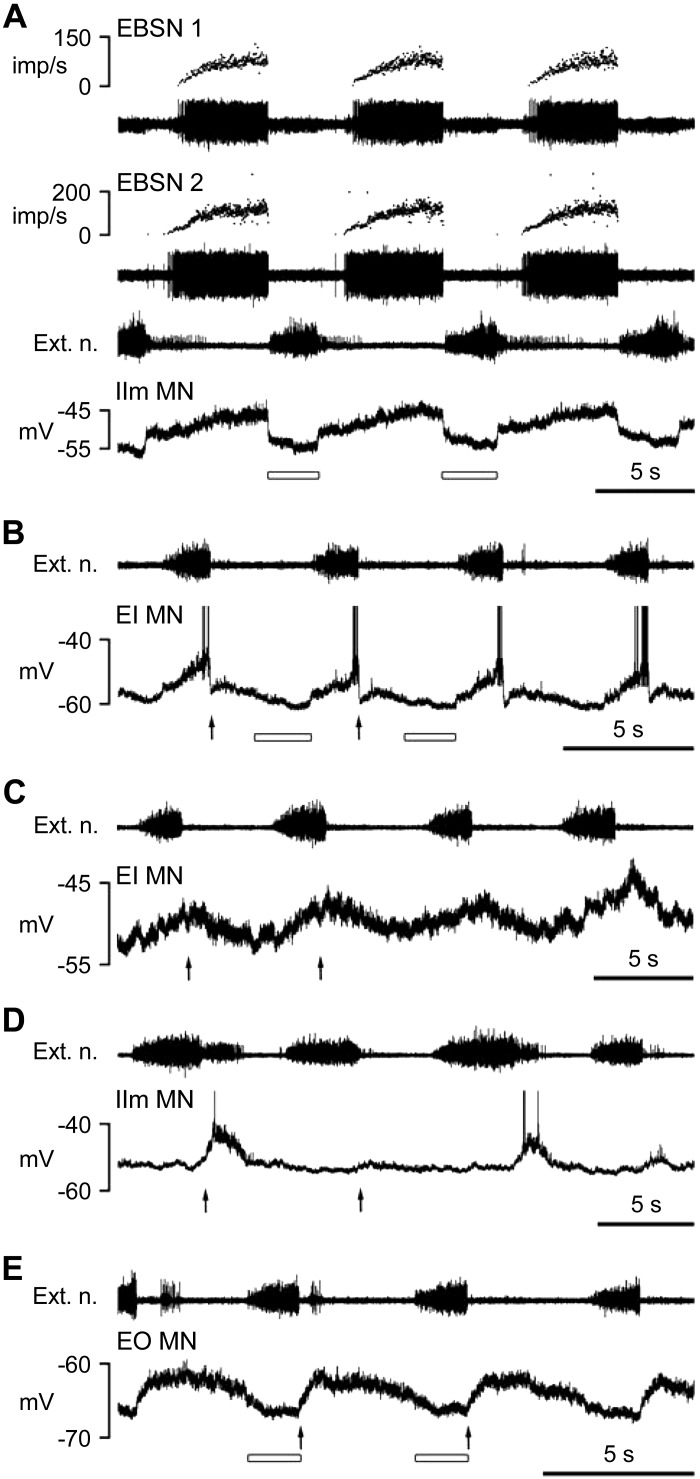

Fig. 3.

Examples of central respiratory drive potentials (CRDPs) of different types from various categories of motoneuron. A: expiratory CRDP, IIm MN. B: inspiratory CRDP, EI motoneuron. C: inspiratory CRDP, with a postinspiratory depolarization a little larger than the inspiratory component, EI motoneuron. D: expiratory decrementing (Edec) CRDP, IIm motoneuron. E: Edec CRDP, EO motoneuron. In each panel, the intracellular recording is shown (bottom trace) with the external intercostal nerve discharge from a more rostral segment in the trace above (Ext. n.). In A, simultaneous recordings from 2 EBSNs are also included with their instantaneous firing frequencies shown above each EBSN recording (imp/s, impulses per second). Arrows in B–E indicate the start times of postinspiratory depolarizations, and the open bars in A, B, and E indicate the periods of probable postsynaptic inhibition (2 cycles indicated in each instance). Spikes in intracellular records in B and D are truncated. For definitions of motoneuron groups, see methods and Fig. 1.

Most of the data (120 acceptable motoneuron recordings; see below) come from 11 animals, where the primary aim was to measure the connections from EBSNs to motoneurons using spike-triggered averaging (STA), but in the other 8 animals (32 acceptable motoneuron recordings) the primary aim was intracellular recording from interneurons (Meehan et al. 2003) and the motoneuron recordings were an inevitable by-product. These animals were vagotomized, and most also received a bilateral pneumothorax. Results did not differ between these two groups, so they are considered together.

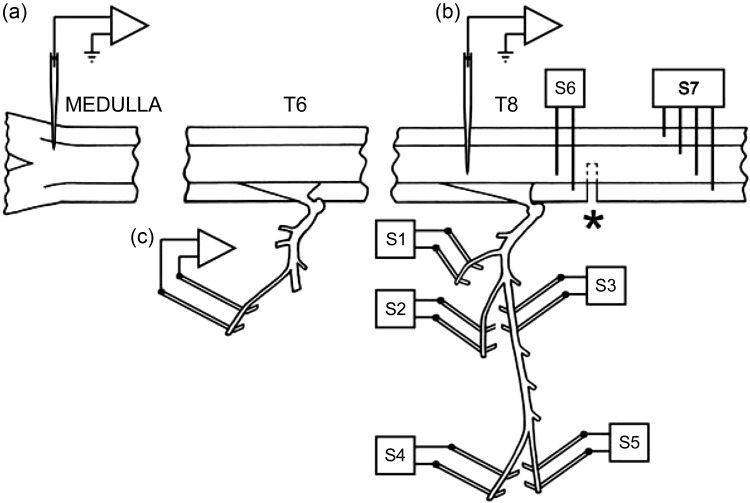

Figure 1 shows the experimental arrangement. Nerves were prepared for stimulation via platinum wire electrodes (Fig. 1, S1–S5) in the left intercostal space innervated by the spinal cord segment immediately above the lesion as described in detail by Saywell et al. (2007): 1) a bundle of dorsal ramus nerves (Kirkwood et al. 1988); 2) the external intercostal nerve; 3) the most proximal point on the internal intercostal nerve (in continuity but arranged to be lifted away from the volume conductor separately from the external intercostal nerve so as to avoid stimulus spread); 4) the lateral branch of the internal intercostal nerve; and 5) the distal remainder of the internal intercostal nerve. These nerves were used for antidromic identification of motoneurons, which therefore fell into five anatomic categories. The first two nerves identified dorsal ramus (DR) motoneurons or external intercostal (EI) motoneurons. Responses to the lateral branch of the internal intercostal nerve identified external abdominal oblique (EO) motoneurons (Sears 1964a), whereas motoneurons excited from the proximal electrodes on the internal intercostal nerve but not from either of the more distal branches were identified as innervating the proximal part of internal intercostal or intracostalis (Sears 1964a) muscles (IIm motoneurons). Those identified from the distal remainder (Dist motoneurons) innervated the distal part of internal intercostal muscle, other abdominal muscles, parasternal intercostal muscle, or triangularis sterni (only at T7). For more detail of the muscles innervated and for references, see Meehan et al. (2004) and Saywell et al. (2007). In the eight experiments aimed primarily at recording from interneurons, the lateral and distal internal intercostal nerve branches were not prepared, and the whole internal intercostal nerve (cut) was stimulated at the proximal site. In these animals, there were thus only three motoneuron categories, DR, EI, and internal intercostal nerve (IIn). A combined category of EO, Dist, IIm, and IIn together (all internal intercostal nerve groups) was defined as IIN. The left external intercostal nerve of a rostral segment (most often T6) was prepared for recording efferent discharges, which were used to define the timing of central inspiration.

Fig. 1.

General experimental arrangement for terminal experiment. Recording microelectrodes are illustrated, extracellular [(a)] for expiratory bulbospinal neurons (EBSNs) and intracellular [(b)] for motoneurons. The recording of efferent discharges [(c)] in a rostral external intercostal nerve was used to determine the timing of inspiration. The stimulating electrodes for antidromic identification of motoneurons are labeled S1–S5, the nerves being as follows: S1, dorsal ramus; S2, external intercostal; S3, proximal internal intercostal; S4, lateral branch of internal intercostal; and S5, distal branch of internal intercostal. See main text for definitions of the motoneurons identified from these nerves. For more details of the muscles innervated, see Meehan et al. (2004) and Saywell et al. (2007). S6 and S7, stimulating electrodes for the spinal cord above and below the lesion (*). Antidromic activation of a neuron from S6, but not from S7, indicated an EBSN with its axon severed in the lesion. The particular segments involved varied (see main text), but the most common were as labeled here (T6 and T8) when the lesion was at rostral T9.

A thoracic laminectomy was made, the dura opened, and small patches of pia removed from the dorsal columns of the segment above the lesion to be used for motoneuron recording. A pair of stimulating electrodes (S6 in Fig. 1) were inserted into the left spinal cord, 1–2 mm rostral to the rostral edge of the scar tissue overlying the lesion, together with another electrode array (S7 in Fig. 1), consisting of two electrode pairs, one on each side of the cord, one or two segments below the lesion, as in Kirkwood et al. (1988). A shaped pressure plate was lightly applied to the cord dorsum of the segment above the lesion to aid mechanical stability. The laminectomy and nerves were submerged in a single paraffin oil pool constructed from skin flaps. In 16 of the animals, an occipital craniotomy was made, the dura opened, and a small patch of pia removed from the right side of the medulla.

Recording procedures.

The activities of EBSNs were recorded extracellularly in the right caudal medulla via glass microelectrodes (broken back to a tip diameter of 3.0–3.2 μm and filled with 3 M NaCl) introduced into the medulla through a hole in a small pressure plate and with conventional amplification. EBSNs within nucleus retroambiguus, ∼3 mm caudal to obex, were identified by their expiratory firing patterns and by antidromic identification from the stimulating electrodes on the left side rostral to the lesion (0.1-ms pulses). They were also tested for antidromic activation from the electrodes caudal to the lesion and only accepted for study if they failed to be activated at this site and were therefore deemed to have been axotomized in the lesion. This is justified by the high proportion (31/34) of EBSN axons that were antidromically activated at T9 and that could also be activated from T11 in uninjured spinal cords (Road et al. 2013). In 4 of the experiments, 2 recording electrodes were used, mounted on separate manipulators, so that 2 EBSNs could be used for STA with each motoneuron.

Intracellular recordings were made from motoneurons on the left side antidromically identified from stimulation of the peripheral nerves (see above) using glass microelectrodes inserted into the cord through the dorsal columns at an angle (tip lateral) of between 10 and 15°. Recordings for most motoneurons were obtained with electrodes of external tip diameter 1.2–1.6 μm (resistance 2–5 MΩ) filled with 3 M potassium acetate, although the electrodes used for eight of the motoneurons had finer tips and were filled with 2% Neurobiotin (Vector Laboratories) in 0.1 M Tris buffer (pH 7.4) and 0.5 M potassium acetate, as used for intracellular labeling of interneurons (Meehan et al. 2003).

Simultaneous recordings from the EBSNs, intracellular recordings from the motoneurons, and the efferent discharges in the rostral external intercostal nerve were stored on magnetic tape and/or acquired for computer analysis (Spike2; CED, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Both a low-gain direct current (DC) version and a high-gain, high-pass filtered (time constant, 50 ms) version of the motoneuron membrane potential (Vm) were included. Extracellular control recordings were also made close to each motoneuron, immediately after the intracellular recording. The rostrocaudal positions of the motoneurons were noted with respect to the most rostral dorsal root on the left of the segment and fell within two regions approximately ±0.5 mm of that rostral root or ±0.5 mm of 5 mm more caudal so as to be consistent with the control data from Saywell et al. (2007).

Analysis.

Two comparisons were made with the control data: first, a description of the types and amplitudes of the central respiratory drive potentials (CRDPs; Sears 1964b) as seen in the DC recording and, second, an analysis of the connectivity between the EBSNs and the motoneurons by STA, usually via the high-gain recording. For STA, the single-unit nature of the EBSN recording was confirmed by the absence of very short intervals in an autocorrelation histogram (0.2-ms bins; examples in Fig. 5A, a and c). The lag to the first peak or the shoulder of the autocorrelation histogram was used to calculate an approximate modal firing frequency of the EBSN (Ford et al. 2000; Kirkwood 1995). Delays in the collision test and latencies in the STA measurements (Fig. 5) were all referred to the early rising phase of the (main) negative-going phase of the trigger spikes (Davies et al. 1985; Kirkwood 1995). Orthodromic conduction times for the EBSNs were calculated from the collision test, as the critical delay minus 0.5 ms (Davies et al. 1985; verified by Kirkwood 1995) and conduction velocities were calculated from these values together with distances from the medulla to the stimulating electrodes. These distances were calculated from a table of values related to the weight of the animal and derived from the animals used by Davies et al. (1985) and Kirkwood (1995). The EBSN conduction time to the appropriate rostral or caudal part of the segment, the “axonal time” (Davies et al. 1985; Kirkwood 1995), was calculated as the orthodromic conduction time to the stimulating electrodes (S6 in Fig. 1) multiplied by d1/d2, where d1 was the distance between electrodes (a) and (b) in Fig. 1 and d2 was the distance between electrode (a) and S6. The collision test was routinely carried out at 2× threshold, but in one instance it was noticed that when the stimulating current was increased to 5–10× threshold, the collision interval (unusually) shortened considerably, by >1 ms. The value at 5× threshold was therefore adopted in this instance, on the assumption that the longer collision intervals arose from the axon being stimulated at sites on fine collaterals (see discussion).

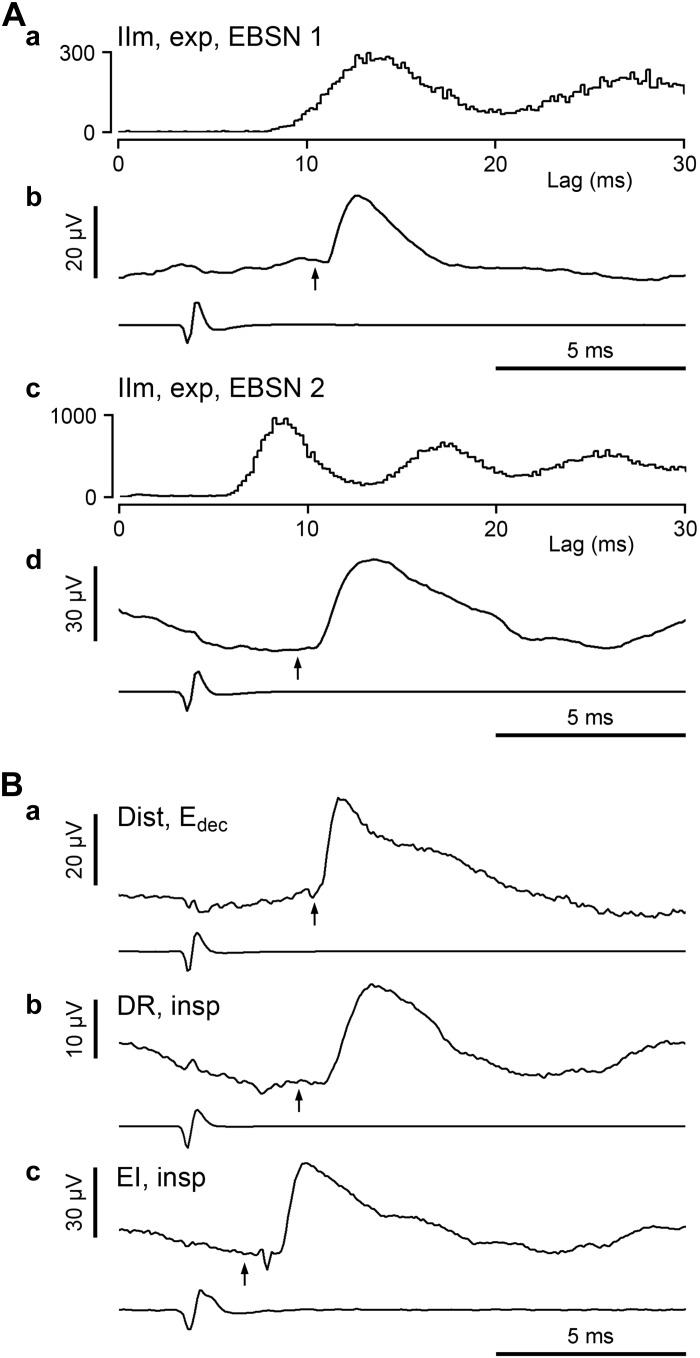

Fig. 5.

Examples of spike-triggered-averaged excitatory postsynaptic potentials (STA EPSPs) recorded in various categories of motoneuron. A: full analysis for the motoneuron illustrated in Fig. 3A (expiratory IIm): a and c, autocorrelation histograms from the top and bottom EBSNs, respectively, in Fig. 3A; b and d, EPSPs averaged, respectively, from those 2 EBSNs. B: STA EPSPs averaged from other motoneurons: a, Edec Dist motoneuron; b, inspiratory DR motoneuron; and c, inspiratory EI motoneuron (the same as in Fig. 3C). The averaged EBSN trigger spike is shown below each EPSP, and the calculated axonal time (see methods) is indicated by the arrow. Numbers of sweeps: Aa, 14,416; Ab, 20,472; Ba, 10,046; Bb, 21,582; and Bc, 11,378.

For motoneurons that were firing spontaneously, trigger spikes near times of spontaneous motoneuron spikes were edited out of the records before analysis so that such spikes could not affect the averages. An essential criterion for an averaged waveform to be accepted as a synaptic potential was that of repeatability; the potential (independent of any judgement about synaptic linkage) had to be present with a similar time course at the same latency in each of three successive averaging epochs (Kirkwood and Sears 1982). Conventional shape indices (Jack et al. 1971; Rall 1967) were measured for synaptic potentials (Fig. 7D), rise times from 10 to 90% amplitude, and durations at 50% amplitude (half-widths).

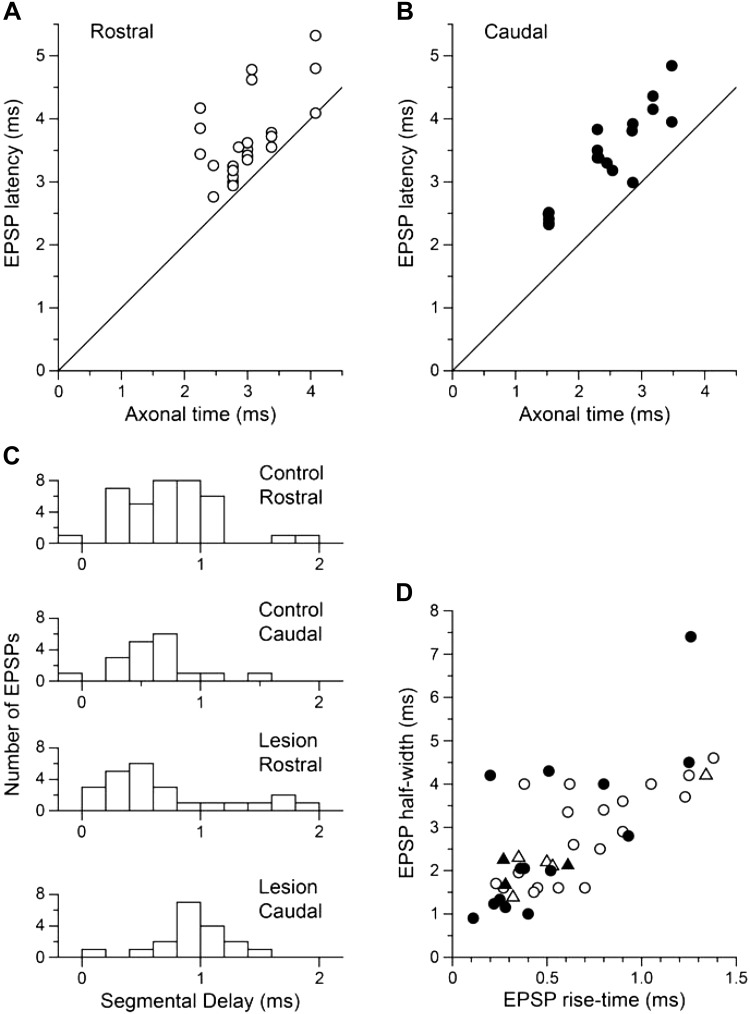

Fig. 7.

Timing characteristics of the EPSPs. A and B: EPSP latencies plotted against the axonal time (the calculated EBSN conduction time to the recording site; see text in results and methods) for the rostral and caudal groups of recordings, respectively. The lines are the lines of identity. C: distributions of segmental delay (difference between EPSP latency and axonal time) for the same 2 groups (lower 2 histograms) compared with equivalent data from the control experiments (upper 2 histograms). D: conventional shape indices for the EPSPs. Open symbols, rostral group; closed symbols, caudal group; circles, EPSPs with segmental delays <1.2 ms; triangles, EPSPs with segmental delays ≥1.2 ms.

Histological procedures.

The histology relevant to these experiments consisted of reconstructions of the extent of the spinal lesions. Animals from the interneuron series were heparinized and perfused through the left ventricle with a saline rinse followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Relevant segments of spinal cord were removed and stored in the same fixative. In the other animals, the segment of the spinal cord containing the lesion was removed and immersion-fixed in 10% formol saline. After an appropriate interval, serial transverse sections through the whole rostrocaudal extent of the lesions were cut and mounted, either wax-embedded, 15 μm, stained with Cresyl violet and Luxol fast blue, or frozen, 50 μm (after cryoprotection in sucrose), stained with neutral red. Outlines of the sections through the lesion were traced via a drawing tube to reconstruct the maximum extent of the lesion (not necessarily all from 1 section). Dark-field illumination was included in this process, being particularly helpful at revealing small areas of myelination, indicating spared portions of fiber tracts (Fig. 2B).

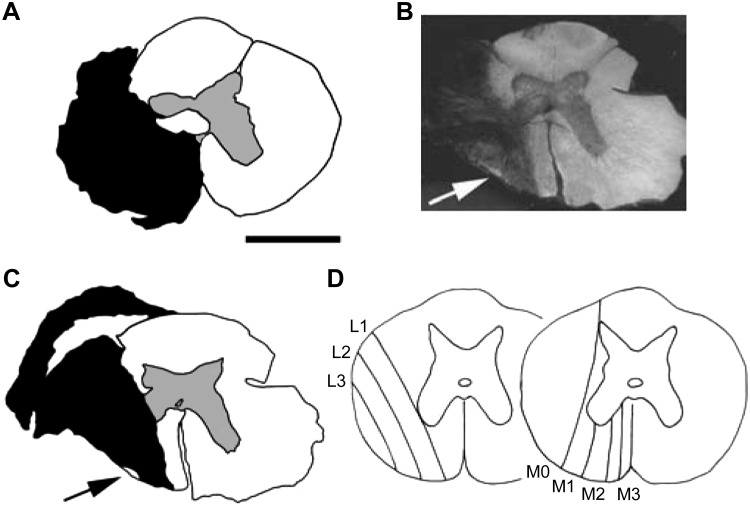

Fig. 2.

Lesions and their classification. Transverse sections of the spinal cord are shown. A: an example of a lesion that was close to ideal. The black area indicates an absence of neurons or intact myelinated fibers. The small clear area extending laterally to the left from the central canal was a small cyst. B: the use of dark-field illumination to help show up small areas of surviving white matter (arrow). C: the reconstruction of the lesion illustrated in B (arrow as in B). D: schematic of the classification of lesion borders: lines L1 to L3 indicate the medial border of spared white matter lateral to the lesion, and lines M0 to M3 similarly indicate the extent of spared white matter medial to the lesion. For both ratings, larger numbers refer to larger lesions. Lesions that were complete laterally or complete to the midline medially were rated L4 or M4, respectively (see main text for more detail). The lesion in A was rated L4/M4, and that in B and C was rated L3/M2 (this lesion was rated L3 rather than L4 solely on account of the very small island of spared white matter, indicated by the arrow). Scale bar, 2 mm for A–C.

Mean values are quoted as ± SD. In statistical tests, P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

RESULTS

Lesions.

The intended lesion was a complete section of all the white matter on the left side except for the dorsal columns. However, as in Ford et al. (2000), only four of the lesions were complete (e.g., Fig. 2A). In the others, some fibers were spared laterally and/or medially within stereotyped locations in the spinal cord sections, probably determined by the shape of the scalpel blade and/or the spinal canal (Fig. 2, B and C). Lesions were therefore rated separately for their lateral and medial extents according to the scheme used by Ford et al. (2000) and as indicated in Fig. 2D. Larger lesions were assigned higher numbers, medially M0 to M4, laterally L1 to L4, where a complete lesion was rated L4/M4. Lesions complete medially and also extending to the right side (4 instances) were rated M5. Laterally, the majority of the lesions (12/19) were rated L4, the remainder L3. Medially, both the modal (7 instances) and the median ratings were M3, and the mean was M3.16. As a group, the lesions were therefore very similar to the 16-wk group of Ford et al. (2000) for their lateral extent but were rather more complete medially. It was important that the ventral roots of the segment above the lesion were not damaged to avoid the possibility of damaged axons reinnervating different muscles and making antidromic identification misleading. All spinal cords were carefully examined before cutting sections. Although the connective tissue scar was usually close to the extradural ventral root, it never included nor adhered to it, so we believe these roots were indeed undamaged.

Motoneuron recordings.

Recordings were only acceptable if they had a baseline Vm less than or equal to −40 mV. This was usually measured, as in Saywell et al. (2007), at the start of expiration on the basis of this being the time in the respiratory cycle where the synaptic excitation or inhibition was likely to be least. However, since in many of the cells in the current experiments we found exaggerated postinspiratory components in the CRDPs, in these cells Vm was measured in late expiration. Values of Vm varied between −40 and −81 mV (mean −54.7 ± 10.2 mV, n = 152).

CRDPs.

Nearly all motoneurons (139/152) demonstrated CRDPs, which were characterized as in Saywell et al. (2007) as: 1) expiratory, with a ramp of excitation during expiration and a ramp of hyperpolarization during inspiration (presumed inhibition, as in Sears 1964b); 2) inspiratory, with a ramp of excitation during inspiration; or 3) expiratory decrementing (Edec), with a depolarization greatest in early expiration and a minimum (often with the appearance of an inhibitory phase) during inspiration (Fig. 3, D and E). As mentioned above, the postinspiratory component of inspiratory neurons was often exaggerated in the lesioned spinal cords, as were the postinspiratory discharges of the external intercostal nerve recorded in a more rostral segment (Fig. 3D). In the control recordings from this category, as in other published data from inspiratory intercostal or phrenic motoneurons, the postinspiratory depolarization most often had an amplitude of only a fraction of the size of the inspiratory depolarization, but in the lesioned spinal cords it was often large, sometimes being larger than that in inspiration. One might think that therefore these motoneurons should be classified as Edec instead of inspiratory. However, the distinction we wish to make is that these inspiratory CRDPs showed a depolarizing ramp during inspiration (e.g., Fig. 3C), whereas those we have classified as Edec usually showed a hyperpolarization in inspiration (e.g., Fig. 3E). Moreover, the postinspiratory component in the inspiratory neurons often varied in amplitude with time during a recording, sometimes in parallel with variation of the postinspiratory component in the nerve discharges, whereas the inspiratory component stayed more or less constant. When we measured the amplitudes of these components, we used a period in the recording when the cell was apparently in the best condition, usually near the start of the recording (Fig. 3, D and E, comes from such periods). This was also often a time when the postinspiratory component was largest. This component, in both the CRDP and the external intercostal nerve discharge, frequently faded with time into a recording. This may have represented a general reduction of excitability after the nerve stimuli used during the antidromic identification procedures had been switched off but by no means entirely: this level of excitability also appeared to wax and wane independently of any applied stimulation. A cycle-by-cycle variability in the postinspiratory component was also relatively common, in either the external intercostal nerve discharge or in the CRDPs, but that in Fig. 3D is an extreme example. There were also a further five motoneurons with CRDPs that did not fit into the previous categories (see Table 1, Other), all of relatively low amplitude.

Table 1.

Numbers and amplitudes of CRDPs of each type for each motoneuron group

| Motoneuron Group | Dist | EO | IIm | IIn | EI | DR | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Lesion | Control | Lesion | Control | Lesion | Control | Lesion | Control | Lesion | Control | Lesion | Control | Lesion | |

| CRDP type | ||||||||||||||

| Insp | ||||||||||||||

| n | 8 | 5 | — | — | — | — | 10 | 4 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 9 | 51 | 35 |

| range, mV | 0.5–13 | 2–13 | — | — | — | — | 3.5–19 | 1–8 | 1–17 | 2–12 | 0.5–4.5 | 0.5–7 | 0.5–19 | 0.5–13 |

| mean, mV | 4.3 | 7.1 | — | — | — | — | 10.1 | 4.4 | 7.3 | 5.8 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 5.8 | 5.0 |

| SD | 4.3 | 4.9 | — | — | — | — | 5.7 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 5.0 | 3.3 |

| Exp | ||||||||||||||

| n | 23 | 26 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 10 | 22 | 10 | — | 1 | 1 | 4 | 73 | 67 |

| range, mV | 0.5–11.5 | 1–12 | 1–11.5 | 1–14 | 1.5–15.5 | 2.5–16 | 1.5–10.5 | 2–12 | — | 2 | 1 | 1–3.5 | 0.5–15.5 | 1–16 |

| mean, mV | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 7.3 | 4.7 | 6.1 | — | — | — | 2.5 | 4.7 | 5.0 |

| SD | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 3.2 | — | — | — | 1.1 | 3.1 | 3.6 |

| (ramps) | ||||||||||||||

| range, mV | 0–6 | 0–7 | 0–5 | 0–8.5 | 0–6 | 0–8.5 | 0–5 | 1–10 | – | 0.5 | 0 | 0–1.5 | 0–6 | 0–10 |

| mean, mV | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 3.5 | — | — | — | 0.5 | 1.8 | 2.4 |

| SD | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 3.0 | — | — | — | 0.6 | 1.6 | 2.5 |

| Edec | ||||||||||||||

| n | 2 | 7 | — | 3 | — | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 13 | 32* |

| range, mV | 2.5, 6 | 1.5–3.5 | — | 2–5.5 | – | 3, 4.5 | 2, 3 | 2, 3.5 | 0.5–4 | 1–8 | 0.5–3 | 0.5–6 | 0.5–6 | 0.5–8 |

| mean, mV | 4.2 | 2.2 | — | 4.2 | — | 3.8 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.8 |

| SD | — | 0.6 | — | 1.5 | — | — | — | — | 1.4 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| Other | ||||||||||||||

| n | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| range, mV | — | — | — | 3 | — | — | — | — | — | 3.5, 4 | 2.5 | 0.5, 0.5 | 2.5 | 0.5–4 |

| mean, mV | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.5 | — | 2.3 |

| ± SD. | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.5 |

| No CRDP | ||||||||||||||

| n | 1 | 2 | — | 2 | 1 | — | 2 | — | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 13 |

| Total (with CRDP) | ||||||||||||||

| n | 33 | 38 | 16 | 20 | 11 | 12 | 34 | 16 | 21 | 29 | 23 | 24 | 138 | 139 |

| range, mV | 0.5–13 | 1–13 | 1–11.5 | 1–14 | 1.5–15.5 | 2.5–16 | 1.5–19 | 1–12 | 0.5–17 | 0.5–12 | 0.5–4.5 | 0.5–7 | 0.5–19 | 0.5–16 |

| mean, mV | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 6.7 | 6.1 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 4.6 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 4.9 | 4.3 |

| SD | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 3.4 |

Data from current experiments (bold) are compared with control data from Saywell et al. (2007) (italics). The central respiratory drive potential (CRDP) category “Other” includes: controls, 1 expiratory-inspiratory; and lesion, 3 inspiratory decrementing (2 EI and 1 DR) and 2 multiphasic (1 EO and 1 DR). The only notable difference between the lesion and control populations (see main text) is in the proportion of expiratory decrementing (Edec) CRDPs (

). For definitions of motoneuron groups, see methods and Fig. 1. Insp, inspiratory; Exp, expiratory.

For all motoneurons, the measurements on the CRDPs included the overall peak-to-peak amplitude. For expiratory CRDPs, we also measured the expiratory ramp amplitude, as in Saywell et al. (2007), and, for inspiratory CRDPs, the maximum depolarization at the end of inspiration and that during postinspiration, both referenced to the most hyperpolarized value, usually at end expiration. These latter measurements for the inspiratory CRDPs were different from those used by Saywell et al. (2007), so the CRDPs from that study were remeasured according to the new criteria, so that they could be directly compared. All of the CRDP measurements, from both studies, were recorded to the nearest 0.5 mV.

Table 1 lists the numbers and amplitudes of the different types of CRDP according to the groups of motoneurons identified by antidromic excitation from the different nerves and compares these with values from the control group from the experiments of Saywell et al. (2007). A few more motoneurons than were listed in the earlier study are now included in this group (those not used then for STA measurements). The group of motoneurons from the lesioned spinal cords also includes some not used for STA. A broadly similar sample of motoneurons from the different nerves is present for the two groups, with the one exception that for the lesion group there was a lower proportion of those in the IIn category compared with those in the Dist, EO, and IIm categories. This reflects only that there was a lower proportion of animals in this study where the two branches of the IIn were not separately stimulated.

The distribution of CRDPs was broadly similar in the lesioned spinal cords to that in the controls. In the combined category IIN (which combines the separate categories IIn, IIm, EO, and Dist), the motoneurons most often showed expiratory CRDPs, whereas inspiratory CRDPs were found most commonly in EI motoneurons or in Dist motoneurons. As previously, DR motoneurons showed a variety of CRDP types. However, one clear difference was found: the proportion of CRDPs classified as Edec was clearly higher for the lesion than for the control groups. This was apparent across all categories of motoneurons, and the difference overall (32/152 vs. 13/146) was significant (χ2, P < 0.001).

Given the starting point of this investigation, the observation of an increase in the physiologically measured EBSN projections in the segment above a lesion (Ford et al. 2000), the distribution of ramp amplitudes for expiratory motoneurons was of obvious interest. Although the mean amplitude was larger for the lesion group than for the controls (2.4 vs. 1.8 mV; Table 1), the populations were not significantly different (Mann-Whitney, P = 0.095, 1-tailed; median 1.5 vs. 1.0 mV). The plasticity described by Ford et al. (2000) was detected only in the caudal half of the segment, so we also looked for a difference in the expiratory ramp amplitudes specifically for the caudally located groups of motoneurons. Again, the mean amplitude was slightly larger for the lesion than for the control group (2.2 vs. 1.8 mV, median 1.75 vs. 1.0 mV, n = 29, n = 32, respectively) but again not significantly so (Mann-Whitney, P = 0.38).

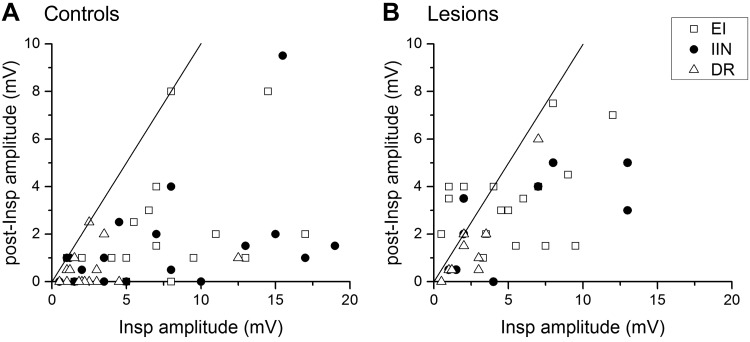

An additional clear difference between lesion and control groups was found within the inspiratory CRDPs. As already mentioned, the postinspiratory component was often exaggerated compared to normal. A quantification of this is shown in Fig. 4, where the postinspiratory amplitude is plotted against the inspiratory amplitude for each inspiratory CRDP of the two populations. Note that there were several examples in the lesion group like that in Fig. 3C, where the postinspiratory amplitude was larger than the inspiratory amplitude (points above the line of equality in Fig. 4B). We measured the ratio of these two parameters for each inspiratory CRDP, and the difference was highly significant between the lesion and control groups (medians 0.57 and 0.19, respectively; Mann-Whitney, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 4.

Comparison between the postinspiratory components of inspiratory CRDPs between cells in lesioned and control spinal cords. The postinspiratory (post-Insp) amplitude is plotted against the inspiratory amplitude for each CRDP in the 3 categories of anatomic motoneuron identification as indicated by the different symbols. For each of the plots, the line is the line of identity. For definitions of motoneuron groups, see methods and Fig. 1.

EBSNs.

The discharges of 31 EBSNs were recorded and used for STA. The firing patterns of the EBSNs were similar to those in unlesioned animals, incrementing ramps of firing frequency, generally restricted to phase 2 expiration (Richter 1982). Moreover, quantitative measures, the mean conduction velocity (57.1 ± 13.0 m/s) and the mean modal firing rate (75.5 ± 46.1 impulses per second), were also similar to those measured for unlesioned animals in this laboratory. Thus, as in Ford et al. (2000), we have no evidence that the physiological properties of the EBSNs in this group axotomized at T8–T10 were different from those previously reported from this laboratory (Kirkwood 1995; Saywell et al. 2007; also see Sasaki et al. 1994), and we assume that the sample here is similar.

STA.

Averages were constructed from the recordings of the above 31 EBSNs and 134 motoneurons, giving 180 EBSN-motoneuron pairs from 15 animals (1–16 motoneurons per EBSN). Each average involved more than ∼1,000 EBSN trigger spikes (range 926-60,630 spikes, median 6,289 spikes). Comparable figures from the control group were 957-22,642 spikes, median 5,233 spikes (n = 170). As in Saywell et al. (2007), averages that showed peak-to-peak noise >10 μV (excluding slow drifts) were rejected. This excluded 18 averages (10%). Comparable figures from the control group were 9 averages (5.3%). Synchrony potentials, characterized by slow rising phases, usually starting earlier than the axonal time (Saywell et al. 2007), were detected in a few motoneurons. Of these, 4 were large enough (amplitudes 17–33 μV) and had sufficiently fast rising phases to have obscured possible excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) of 10 μV or more in amplitude, which led to the elimination of these averages (2.2%). The equivalent figure from the control group was 7 averages (3.9%).

EPSPs were detected in 42 of the remaining 158 averages (Fig. 5), ranging in amplitude from 4 to 204 μV. In 12 of these averages, synchrony potentials were also detected (verified by repeatability) but were either small or slowly rising enough not to hide a 10-μV EPSP, sometimes appearing as a clearly separate, slowly rising “foot” preceding the EPSP (e.g., Fig. 5Ba). The EPSPs were distributed as indicated in Table 2, which also compares their distribution with those from the control experiments. The table is arranged similarly to Table 2 in Saywell et al. (2007) except that, because of the prominence of Edec CRDPs in the present data, this category is now listed separately. Other minor numerical changes may be noticed compared with the previous table. These result from our rechecking the control data and recalculating where required. Control and lesion populations (compare italics vs. bold in each category) were generally similar with regard to mean EPSP amplitudes. The apparently large differences in some of the smaller subgroups are to be expected, given the small numbers and the very wide ranges of amplitudes. There seemed to be consistent differences between the lesion and control groups in the proportions of the connections, these being generally lower in the lesion groups, but none of these differences was significant (χ2, P > 0.05). The difference for the one category where the lesion group showed a higher proportion of connections (motoneurons with Edec CRDPs) was also not significant (Fisher exact test, P = 0.08).

Table 2.

Number and amplitudes of EPSPs in motoneurons of different groups

| Amplitude, μV |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity |

Mean |

Effective Mean |

||||

| Group | Control | Lesion | Control | Lesion | Control | Lesion |

| IIN motoneurons with expiratory CRDPs | ||||||

| Dist | 16/26 (62%) | 10/31 (32%) | 22.2 | 35.0 | 13.6 | 11.3 |

| EO | 12/20 (60%) | 6/16 (38%) | 41.9 | 20.1 | 25.1 | 7.5 |

| IIm | 8/12 (75%) | 7/13 (54%) | 39.8 | 87.5 | 31.9 | 47.1 |

| IIn | 8/22 (36%) | 3/5 (60%) | 79.3 | 24.9 | 28.8 | 14.9 |

| Total IIN exp. | 44/80 (55%) | 26/65 (40%) | 41.1 | 44.5 | 21.1 | 17.8 |

| Motoneurons with inspiratory CRDPs | ||||||

| Dist | 1/11 | 0/5 | 15.0 | — | 1.4 | — |

| IIn | 2/8 (25%) | — | 9.3 | — | 2.3 | — |

| EI | 2/16 (13%) | 3/20 (15%) | 38.2 | 39.2 | 5.1 | 5.9 |

| DR | 3/14 (23%) | 1/10 (10%) | 19.7 | 16.7 | 4.2 | 1.7 |

| Total insp. | 8/49 (16%) | 4/35 (11%) | 20.1 | 33.5 | 3.3 | 3.8 |

| Motoneurons with Edec CRDPs | ||||||

| Dist | 0/1 | 6/10 (60%) | — | 14.7 | — | 8.8 |

| EO | — | 1/4 (25%) | — | 33.9 | — | 8.5 |

| IIm | — | 1/4 (25%) | — | 7.5 | — | 1.9 |

| IIn | 0/2 | 0/1 | — | — | — | — |

| EI | 0/5 | 2/9 (22%) | — | 17.3 | — | 8.8 |

| DR | 1/5 (20%) | 2/11 (18%) | 34.0 | 14.4 | 6.8 | 2.6 |

| Total Edec | 1/13 (8%) | 12/39 (31%) | 34.0 | 33.6 | 2.6 | 4.9 |

| Motoneurons with other CRDPs and no CRDP | ||||||

| Dist | 0/1 | 0/1 | — | — | — | — |

| EO | — | 0/1 | — | — | — | — |

| IIm | 0/1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| IIn | 0/2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| EI | 1/2 (50%) | 0/4 | 65.0 | — | 32.5 | — |

| DR | 1/6 (17%) | 0/13 | 6.0 | — | 1.0 | — |

| Total other | 2/12 (17%) | 0/19 | 35.5 | — | 5.9 | — |

| Grand total | 55/154 (36%) | 42/158 (27%) | 37.7 | 35.3 | 13.5 | 9.4 |

| Rostral vs. caudal parts of the segment | ||||||

| Rostral IIN exp | 28/49 (57%) | 16/34 (47%) | 39.8 | 31.0 | 20.7 | 14.6 |

| Rostral all other | 9/57 (16%) | 8/46 (18%) | 20.5 | 16.5 | 3.2 | 2.9 |

| Caudal IIN exp | 16/31 (52%) | 10/31 (32%) | 43.3 | 64.7 | 23.9 | 20.9 |

| Caudal all other | 2/17 (12%) | 8/47 (17%) | 40.5 | 24.3 | 4.8 | 4.1 |

Data from current experiments (bold) are compared with control data from Saywell et al. (2007) (italics). The “effective mean” includes all pairs tested for that group with absence of an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) assigned an amplitude of 0. For definitions of motoneuron groups, see methods and Fig. 1.

Given the starting point of this study (Ford et al. 2000), we were particularly interested in possible increased connections in the caudal half of the segment for the lesion group. The “effective mean,” which shows the mean amplitude, including all tested motoneurons (nonconnections being counted as 0 amplitude), should be the most appropriate measure to indicate increased connections. Clearly, no such increase was seen (Table 2, Rostral vs. caudal parts of the segment).

Relation between EPSPs and CRDPs.

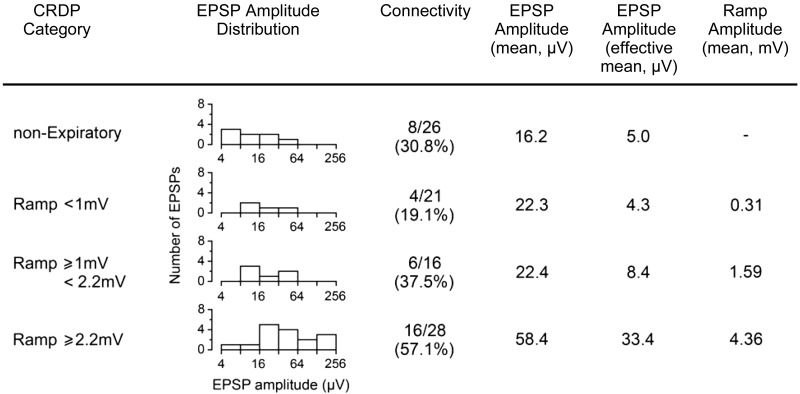

Even without the occurrence of a detectable increase in the overall connectivity with motoneurons, more subtle changes might be seen in the distributions of the connections within that pool. We have therefore investigated the variation in the distribution of EPSP amplitudes to motoneurons with different strengths of expiratory input. In Saywell et al. (2007), a clear relationship was present, where the motoneurons having the larger expiratory ramps showed both larger and more frequent connections. Figure 6 shows that this was also true for the lesion population, using the same borderlines for ramp amplitude as previously. In particular, the effective mean amplitude showed a steady increase across the groups of increasing ramp amplitude. Note that although there was an apparently higher connectivity in the “nonexpiratory” group (8/26 connections, effective mean 5.0 μV) compared with the same group in Saywell et al. (2007), where there were only 2/24 connections, effective mean 0.8 μV, this was entirely the result of the increased number of Edec motoneurons in the lesion group. Within the nonexpiratory subgroup, the Edec motoneurons received all of the connections (8/19, effective mean 6.8 μV).

Fig. 6.

Summarized EPSP and CRDP parameters for IIN motoneurons. EPSP amplitudes are grouped according to CRDP amplitude and displayed graphically (note the log scale). For the definition of effective mean amplitude, see main text and Table 2.

EPSP latencies and time courses.

Another way in which plasticity in the EBSN terminals might be revealed is in changes in the time parameters for the EPSPs. To investigate this, we first compared the latencies of the EPSPs with their axonal times (the calculated stem axon EBSN conduction times to the rostrocaudal position of the recording) as in Saywell et al. (2007; cf. de Almeida and Kirkwood 2013; Road et al. 2013) and plotted in Fig. 7, A and B. For both rostral and caudal groups, the latencies show a clear relationship with the axonal time, thus distinguishing these EPSPs from synchrony potentials, where no relationship is apparent (Davies et al. 1985; Saywell et al. 2007). The values for latency are grouped a little above the line of equality but rather differently for the rostral and caudal groups, the former showing more scatter, with both more points on or close to the line of equality and more points further away. Figure 7C shows this explicitly, where the distributions of the segmental delay (the difference between EPSP latency and axonal time) are plotted for the rostral and caudal groups for both the control and lesion populations. A large part of the segmental delay consists of the conduction time in axon collaterals (Kirkwood 1995). Newly formed collaterals or extensions of existing collaterals may be particularly fine and/or extensively branched. Thus, from an expectation of more sprouting in the caudal area, a larger value for segmental delay or more variability for the caudal group than for the rostral group might be expected.

The means and SDs of these distributions were: control rostral, 0.74 ± 0.39 ms (n = 37); control caudal, 0.58 ± 0.34 ms (n = 18); lesion rostral, 0.71 ± 0.56 ms (n = 24); and lesion caudal, 0.94 ± 0.31 ms (n = 18). Consistent with our expectation, the mean delay for the caudal lesion group was the longest of these four, although it was the lesion rostral group that showed the most variability (the greatest SD). Application of a Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences between the populations (P = 0.012), with Dunn post hoc test implicating the comparisons between the caudal lesion group and each of the other three as being responsible.

The data of Fig. 7 are also relevant to an implicit assumption, which is, following Saywell et al. (2007), that the observed EPSPs represent monosynaptic connections. However, for the rostral group, some of the shortest segmental delays are rather too short even for a monosynaptic connection, and some of the later ones (up to nearly 2 ms) would allow for a disynaptic connection. We will return to this issue in discussion, but with regard to the particularly short delays it should be noted that there were several EBSNs reported by Ford et al. (2000), particularly in the 16-wk lesion groups, where axonal potentials were observed in the extracellular averages with latencies shorter than the calculated axonal times (by >0.2 ms). For estimating the segmental delays for these units, Ford et al. (2000) used the directly observed axonal times in place of axonal times calculated from the collision test. Here, we saw very few axonal potentials, probably because our averages were all made at sites within the motor nuclei, whereas those for Ford et al. (2000) included sites beyond these, including in or very close to the white matter. A number of terminal potentials were seen here, occurring for 26 EBSN-motoneuron pairs, including extracellular controls (12 EBSNs), e.g., Fig. 5B, a and c, some of these being at latencies shorter than the calculated axonal times. Figure 5Ba includes one of these. In this case, the terminal potential was small (but repeatable) and only just ahead of the axonal time (arrow in the figure). Like axonal potentials, terminal potentials have time courses that are too short to arise via presynaptic synchrony, so these are in themselves evidence for some overestimation of the axonal times, supporting this as a likely explanation for the shortest of the EPSP latencies (see discussion).

With regard to the other possible problem, the EPSPs with rather long segmental delays, we have investigated the possibility that these might arise from disynaptic connections by separately indicating examples with segmental delay ≥1.2 ms on a conventional shape-index plot (Jack et al. 1971), with a view that disynaptic EPSPs would be likely to have longer rise times than those generated monosynaptically (Fig. 7D). The overall distribution of rise time and half-width values here is very similar to that in Fig. 6 of Saywell et al. (2007), which itself is similar to others in the literature for monosynaptic single-axon EPSPs (for references, see Saywell et al. 2007). There were eight examples with long segmental delays, but only one of these EPSPs had an extreme value for 10–90% rise time (1.34 ms), and this value itself is still within typical normal ranges (e.g., Jack et al. 1971).

DISCUSSION

We originally set out to look for changes in the connectivity of EBSNs in the segment above and ipsilateral to a spinal cord lesion for which previous experiments using extracellular recording had indicated increased EBSN terminal projections. We did not find any significant changes in EBSN connections to motoneurons that would correspond to the change in projections. However, we did observe a different form of plasticity, a change in the distribution of CRDP types in the motoneurons. We will deal with this first.

Plasticity in CRDPs.

Significant increases in the proportion of Edec CRDPs and in the amplitudes of the postinspiratory components in the inspiratory CRDPs were seen compared to the control experiments. These may represent separate phenomena, but the simplest explanation, given the apparently uniform increase in the occurrence of Edec CRDPs across all categories of motoneurons, is that, following the lesion, there was a general addition of a postinspiratory excitatory component to any motoneuron, including those that were previously expiratory and those that were previously inspiratory. In previous recordings in both thoracic and lumbar motoneurons, Edec CRDPs appeared to include an inhibitory component during inspiration (Ford and Kirkwood 2006; Kirkwood et al. 2002; Saywell et al. 2007; Wienecke et al. 2015). This component may or may not also have been generally increased, but if it was, it would not appear to have been large in the inspiratory motoneurons, or their definition as inspiratory, by virtue of showing an inspiratory ramp, would not apply.

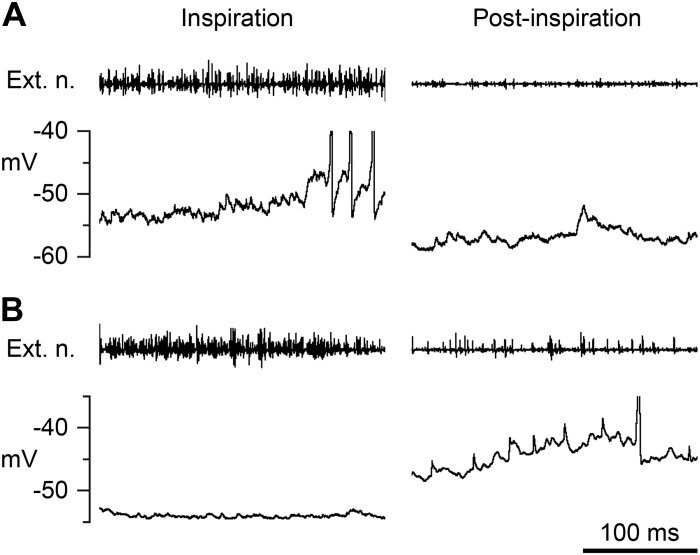

The occurrence of this increased excitation in postinspiration in the segment above a lateral lesion is not entirely new. It was seen by Kirkwood et al. (1984) in external intercostal nerve discharges (see Fig. 2 there) but was not then separated from the tonic excitation that could occur throughout expiration, particularly in the context of similar activity in more caudal segments below the lesion. Tonic excitation was not observed in the external intercostal discharges in the present experiments. However, the recordings of these discharges here were made two to three segments rostral to the lesion rather than in the segment next to the lesion, and hypercapnia was used here throughout rather than the hypocapnia that was used to reveal the tonic excitation by Kirkwood et al. (1984). The tonic excitation seen previously in external intercostal motoneurons was associated with large-amplitude, synchronized synaptic noise and a respirator-phased stretch-reflex excitation. Here, neither of these was obvious, although large-amplitude synaptic noise, usually having the appearance of individual EPSPs or inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), was specifically noted in a number of motoneurons. Such noise was probably the reason why a relatively large proportion of STA averages (10%) were rejected because of high baseline noise. In particular, large-amplitude EPSPs could often be seen during postinspiratory depolarizations. The small deflections of amplitude 2–4 mV during postinspiration in Fig. 3, B and D, which could be confused for miniature spikes when seen on the time scale used in the figure, were actually EPSPs, as was apparent when the recordings were examined on a faster time scale (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Synaptic noise in postinspiration. Expanded traces from 2 of the recordings in Fig. 3 to illustrate the synaptic noise present in postinspiration (right). For comparison, similar extracts from the preceding inspiration are included on the left. A: from the inspiratory EI motoneuron in Fig. 3B (2nd respiratory cycle). B: from the Edec IIm motoneuron in Fig. 3D (1st respiratory cycle). Each top trace is the external intercostal nerve recording. The 3 motoneuron spikes in A during inspiration and the 1 in B during postinspiration are truncated. The time calibration applies to all panels.

The tonic excitation observed by Kirkwood et al. (1984) was interpreted as originating in interneurons, released by the lesions from descending controls. We suggest the same is likely to be the case here, however, in the absence of the synchronization and the stretch reflex, probably not the same interneurons. We suggest interneurons as the source, rather than an increased input from descending fibers, because Edec bulbospinal neurons have very rarely been seen (Boers et al. 2005; Ezure 1990; Ford and Kirkwood 2006; Miller et al. 1985), and none was seen during this series, nor did we see any appreciable postinspiratory discharge in any of the EBSNs recorded here. Nevertheless, we cannot totally exclude an increased Edec input from the medulla (for instance, if there was a population of Edec bulbospinal neurons that were small and hard to record from and hence as yet unidentified).

As for the suggestion of a “release” phenomenon, rather than longer term plasticity, we can again only follow the logic of Kirkwood et al. (1984), where an increased postinspiratory component of the external intercostal nerve discharges was recorded as early as 3 days postlesion (Kirkwood et al. 1984, Fig. 2A). Here, only the one time point (16 wk postlesion) was studied. One minor caveat that must also be kept in mind when comparing the present results with those of Kirkwood et al. (1984) is that in the previous study the ipsilateral dorsal columns were sectioned, whereas here they were generally spared.

The question can be asked as to whether the increased postinspiratory components were part of a useful functional adaptation to the changed mechanical circumstances following the lesions. First, it should be noted that such mechanical changes are not as large as one might imagine. It is not the case that the previously balanced drive to adjacent intercostal spaces would have been lost; the situation here should have been the same as in the experiments of Kirkwood et al. (1984), where the respiratory output in the segments below the lesion was restored to near normal levels (albeit including a tonic component). In any case, if the increased postinspiratory components did comprise a functional adaptation, such an adaptation should be considered as plasticity, not a reflex effect, since the mechanical circumstance during the experiments, with neuromuscular blockade and artificial ventilation, should have been the same in the present experiments as in the controls. It can also be argued that if the adaptation is functional, it is likely that the function concerned is not respiratory because the additional excitation seemed to be very general, to all classes of motoneuron, and not selective to one or other layer or region of the thorax. However, this argument cannot be conclusive given our limited understanding of the functional synergies of the muscles concerned (see discussion in Ford et al. 2014).

The functional role of the postinspiratory components of excitation in general nevertheless needs some consideration. Easton et al. (1999) argued against a commonly accepted view (Remmers and Bartlett 1977) that this component had a specific respiratory role, that of slowing the early expiratory airflow, by pointing out that in the awake dog the component was much larger for the interosseous intercostals than for the more important inspiratory muscles, the parasternal intercostals. Here, there was no apparent difference for the postinspiratory-to-inspiratory ratio between the EI and the IIN motoneurons for either the control or the lesion populations (Fig. 4). However, this does not mean that we are therefore arguing for a specific respiratory function. The great variability and apparent independence between the inspiratory and postinspiratory components rather argues the reverse. One new clue as to a possible function for this component has come from recent analyses of the respiratory drive in hindlimb motoneurons. This drive is most often of the Edec type (Ford and Kirkwood 2006), and it now seems most likely, at least in the decerebrate, that this signal is transmitted via the central pattern generator for locomotion, allowing the locomotor drive to be synchronized to the respiratory one (Wienecke et al. 2015). In the medulla, from Richter (1982) onward, postinspiratory neurons have been assigned important roles in the generation of the normal respiratory pattern (e.g., Smith et al. 2007). These observations might suggest a more general role for postinspiratory neurons in phase transitions, throughout the medulla and spinal cord, although what is seen in lumbar motoneurons, as here, is postinspiratory excitation, whereas the role of these neurons in the medulla is believed to be inhibitory. Postinspiratory interneurons are common in the thoracic segments (Kirkwood et al. 1988), including both excitatory and inhibitory types (Schmid et al. 1993), but, as pointed out by Saywell et al. (2007), the fact that they demonstrate this respiratory pattern in the anesthetized animal under hypercapnia may merely reflect a default behavior under this particular condition. In an awake animal, they could reflect whatever rhythmic drive is dominant at any one time. This view could be seen as a more general expression of the hypotheses put forward by Dutschmann et al. (2014), where the rather particular nonrespiratory role of postinspiratory neurons in controlling the airway-defensive actions of the laryngeal adductor muscles was emphasized. In the conditions of the present experiments, we do not know why the drive from these inputs to thoracic motoneurons should be exaggerated. Perhaps it simply reflects their ubiquity.

Finally, one might consider whether the increase in postinspiratory depolarization might represent a change in intrinsic motoneuron properties. We made no attempt to measure such properties, but one could note that the increased depolarization was seen both in Edec motoneurons, where it followed a presumed inhibition, and in inspiratory motoneurons, where it followed a depolarization. Moreover, for CRDPs such as that illustrated in Fig. 3D, where the large postinspiratory depolarizations are strongly linked to similar behavior in the more rostral external intercostal nerve discharges, it seems most likely that a strong synaptic excitation is involved, which is also consistent with the large individual EPSPs occurring at these times (Fig. 8).

Absence of plasticity in the EBSN connections.

The distribution of EBSN EPSPs in the motoneurons of the segment above lesions was remarkably similar to that in the controls. This was despite the considerable deafferentation that was likely for the motoneurons and the severance of the EBSN axons in the lesions. The expectation from the plasticity in EBSN projections reported earlier (Ford et al. 2000) was that the connections might have become stronger. If anything, they were found to be weaker, although not significantly so. The one category of connections that appeared stronger, although again not significantly so, that to the Edec motoneurons, would also probably not represent a real increase in connections to the motoneurons concerned, even if the change had been significant, since we cannot know how these motoneurons would have been defined before the lesions. For many of these (in the IIN category), their CRDPs could previously have shown small expiratory ramps, which would have needed the addition of only a relatively small postinspiratory depolarizing component to be converted to an Edec time course.

Of course, we do not know whether any of the connections were actually the same as before the lesions or whether in the intervening 16 wk a series of changes had occurred, ending up with connections in the same proportions and specificities as originally. This is why we looked carefully at the EPSP segmental delays. Whereas the variations in segmental delay do allow for a certain amount of sprouting (indeed, the significantly larger values for segmental delay for the caudal lesion group can be taken as positive evidence in this regard), this does not necessarily mean that the EPSPs involved have arisen via collateral sprouts, such as if the original connections had withdrawn and then had been reestablished via new collaterals. It is equally likely that existing collaterals had produced sprouts to new targets and the presence simply of more branch points or changes to the extent of myelination had produced slower conduction along the collaterals.

With regard to verification of the EPSPs as being monosynaptic, note first that some of the unusually short segmental delays could occur as a result of an overestimate of the axonal time, as described in results. This can occur if the antidromic activation in the collision test had occurred at sites on collaterals instead of on the stem axon, as for the one EBSN noted in methods, but it could also occur if the main axon conduction velocity had itself been reduced in the few millimeters rostral to the lesion. Some such artifactually short segmental delays could be one factor involved in the larger SD seen in the population of rostral segmental delays in the lesion group. Second, note that for the segmental delays that are unusually long (up to nearly 2 ms) there is certainly time for a disynaptic connection but also that in the control group there was a similar tail in the distribution of segmental delays, as there was for Ford et al. (2000) for focal synaptic potentials, supported then by an equivalent distribution of terminal potentials. The terminal potentials have time courses too short to have been recorded over a disynaptic link. Moreover, in any population of single-fiber EPSPs, there are usually a few with abnormally long latencies as a result of long or branched collaterals (e.g., Fig. 9D in Kirkwood 1995) and/or by virtue of an origin in a dendritic location. Only when a clearly separate population of motoneurons with appropriately long segmental delays can be independently identified is it valid to conclude that a population of di- (or oligo-) synaptic connections exists (de Almeida and Kirkwood 2013).

Overall, therefore, this study has emphasized the stability in the EBSN connections to motoneurons despite the extended EBSN projections identified by Ford et al. (2000). However, at least two possibilities still exist for these projections. The first is connections to interneurons. Plentiful interneurons with expiratory activity are present in the thoracic spinal cord under the conditions of these experiments (Kirkwood et al. 1988), and their expiratory activity is almost certainly ultimately derived from EBSNs. Although such connections to interneurons have yet to be demonstrated, one could speculate that the (nonsignificant) increase in the expiratory ramp amplitude observed here was the result of increased oligosynaptic connections via local interneurons. The second possibility is that of connections to γ-motoneurons, which are not generally sampled in an intracellular survey.

Therapeutic implications.

New connections made via sprouting or by regeneration in the injured spinal cord might be either useful (restoring function) or deleterious (e.g., leading to spasticity, pain, or autonomic dysreflexia). If treatments are to be given to encourage new connections, it will be an advantage to know just what connections are formed. Furthermore, as many different systems of neurons as possible need to be studied since the different descending systems respond to injury in different ways (Zörner et al. 2014). Considerable attention in recent years has been given to detour pathways, where new connections may be made via existing descending axons spared by the injury. However, as pointed out by Takeoka et al. (2014), the number of circuit elements in the spinal cord and brain stem, together with our lack of understanding of their precise organization and function, often makes mechanistic interpretation of recovery difficult. This may still be true even with relesioning of a presumed detour pathway, which might identify the white matter funiculus involved, or even the region with synaptic connections, but still not the details of which fibers and which connections. In contrast, here we have studied a system of neurons where both the long descending fibers and the motoneuron targets were functionally identified. No significant changes were detected in the connections. Thus, although we can identify neither the actual targets of the sprouting that we believe had taken place nor any specificity in these connections, we can say with certainty that the plasticity in the EBSN axons did not have deleterious effects via their connections to α-motoneurons. Furthermore, the limited response here of the EBSN axons to injury adds one more example to the spectrum of responses demonstrated by different neuronal types. In the longer term, among the different systems of neurons to be studied, a particular focus must be on propriospinal interneurons (Filli and Schwab 2015) despite their heterogeneity and difficulties of categorization (Arber 2012). The present results are entirely consistent with this idea both because of the increased likelihood that the targets of EBSN sprouting (now that ipsilateral α-motoneurons have been ruled out) are interneurons and because the observed plasticity in the CRDPs is likely to arise from interneurons. In the most general terms, this should be of no surprise, since interneurons comprise both the major target of most descending fiber systems and also the source of most motoneuron inputs.

GRANTS

The work was funded by the International Spinal Research Trust. C. F. Meehan held a Medical Research Council (MRC) Studentship.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.W.F., N.P.A., and P.A.K. conception and design of research; T.W.F., N.P.A., C.F.M., and P.A.K. performed experiments; T.W.F., N.P.A., C.F.M., and P.A.K. analyzed data; T.W.F., N.P.A., C.F.M., and P.A.K. interpreted results of experiments; P.A.K. prepared figures; P.A.K. drafted manuscript; T.W.F., C.F.M., and P.A.K. edited and revised manuscript; T.W.F., C.F.M., and P.A.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to the late S. A. Saywell for assistance in some experiments, to K. Sunner for histological assistance, and to the animal care staff of the Institute of Neurology for their dedicated attention to the operated animals.

Present address of T. W. Ford: Univ. of Nottingham School of Health Sciences, Queen's Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2HA, UK.

Present address of C. F. Meehan: Dept. of Neuroscience and Pharmacology, 33.3 Panum Institute, Blegdamsvej 3, 2200 København N, Denmark.

REFERENCES

- Anissimova NP, Saywell SA, Ford TW, Kirkwood PA. Dissociation between inspiratory and post-inspiratory components in the excitation of external intercostal motoneurones in the cat following lesions of the spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci 12, Suppl 11: 333, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anissimova NP, Saywell SA, Ford TW, Kirkwood PA. Distributions of EPSPs from individual expiratory bulbospinal neurones in the normal and the chronically lesioned thoracic spinal cord. XXXIV Int Congress Physiol Sci: Abstr 1029, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arber S. Motor circuits in action: specification, connectivity, and function. Neuron 74: 975–989, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanian VL, Bowers WJ, Anderson A, Horner PJ, Federoff HJ, Mendell LM. Combined delivery of neurotrophin-3 and NMDA receptors 2D subunit strengthens synaptic transmission in contused and staggered double hemisected spinal cord of neonatal rat. Exp Neurol 197: 347–352, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bareyre FM, Kerschensteiner M, Raineteau O, Mettenleiter TC, Weinmann O, Schwab ME. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci 7: 269–277, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MI, Parker D. Changes in functional properties and 5-HT modulation above and below a spinal transection in lamprey. Front Neural Circuits 8: 148, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boers J, Ford TW, Holstege G, Kirkwood PA. Functional heterogeneity among neurons in the nucleus retroambiguus with lumbosacral projections in female cats. J Neurophysiol 94: 2617–2629, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conta AC, Stelzner DJ. Differential vulnerability of propriospinal tract neurons to spinal cord contusion injury. J Comp Neurol 479: 347–359, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conta Steencken AC, Smirnov I, Stelzner DJ. Cell survival or cell death: differential vulnerability of long descending and thoracic propriospinal neurons to low thoracic axotomy in the adult rat. Neuroscience 194: 359–371, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conta Steencken AC, Stelzner DJ. Loss of propriospinal neurons after spinal contusion injury as assessed by retrograde labeling. Neuroscience 170: 971–980, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Song B, Roy RR, Zhong H, Herrmann JE, Ao Y, Qi J, Edgerton VR, Sofroniew MV. Recovery of supraspinal control of stepping via indirect propriospinal relay connections after spinal cord injury. Nat Med 14: 69–74, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JG, Kirkwood PA, Sears TA. The detection of monosynaptic connexions from inspiratory bulbospinal neurones to inspiratory motoneurones in the cat. J Physiol 368: 33–62, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida AT, Kirkwood PA. Specificity in monosynaptic and disynaptic bulbospinal connections to thoracic motoneurones in the rat. J Physiol 591: 4043–4063, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Jones SE, Subramanian HH, Stanic D, Bautista TG. The physiological significance of postinspiration in respiratory control. Prog Brain Res 212: 113–130, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton PA, Hawes GH, Rothwell B, De Troyer A. Postinspiratory activity of the parasternal and external intercostal muscles in awake canines. J Appl Physiol 87: 1097–1101, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezure K. Synaptic connections between medullary respiratory neurons and considerations on the genesis of respiratory rhythm. Prog Neurobiol 35: 429–450, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J. Repair of spinal cord injuries: where are we, where are we going? Spinal Cord 40: 615–623, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filli L, Schwab ME. Structural and functional reorganization of propriospinal connections promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res 10: 509–513, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JR, Graham BA, Galea MP, Callister RJ. The role of propriospinal interneurons in recovery from spinal cord injury. Neuropharmacology 60: 809–822, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford TW, Kirkwood PA. Respiratory drive in hindlimb motoneurones of the anaesthetized female cat. Brain Res Bull 70: 450–456, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford TW, Meehan CF, Kirkwood PA. Absence of synergy for monosynaptic group I inputs between abdominal and internal intercostal motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 112: 1159–1168, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford TW, Vaughan CW, Kirkwood PA. Changes in the distribution of synaptic potentials from bulbospinal neurones following axotomy in cat thoracic spinal cord. J Physiol 524: 163–178, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack JJ, Miller S, Porter R, Redman SJ. The time course of minimal excitatory post-synaptic potentials evoked in spinal motoneurones by group Ia afferent fibres. J Physiol 215: 353–380, 1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA. Synaptic excitation in the thoracic spinal cord from expiratory bulbospinal neurones in the cat. J Physiol 484: 201–225, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Lawton M, Ford TW. Plateau potentials in hindlimb motoneurones of female cats under anaesthesia. Exp Brain Res 146: 399–403, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Munson JB, Sears TA, Westgaard RH. Respiratory interneurones in the thoracic spinal cord of the cat. J Physiol 395: 161–192, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Sears TA. Excitatory post-synaptic potentials from single muscle spindle afferents in external intercostal motoneurones in the cat. J Physiol 322: 287–314, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Sears TA, Westgaard RH. Restoration of function in external intercostal motoneurones of the cat following partial central deafferentation. J Physiol 350: 225–251, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Schmid K, Sears TA. Functional identities of thoracic respiratory interneurones in the cat. J Physiol 461: 667–687, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Sears TA, Tuck DL, Westgaard RH. Variations in the time course of the synchronization of intercostal motoneurones in the cat. J Physiol 327: 105–135, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan CF, Ford TW, Kirkwood PA. Dendritic and possible axonal sprouting by thoracic interneurons in the lesioned spinal cord (Program No. 498.6). In: 2003 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan CF, Ford TW, Road JD, Donga R, Saywell SA, Anissimova NP, Kirkwood PA. Rostrocaudal distribution of motoneurones and variation in ventral horn area within a segment of the feline thoracic spinal cord. J Comp Neurol 472: 281–291, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD, Ezure K, Suzuki I. Control of abdominal muscles by brain stem respiratory neurons in the cat. J Neurophysiol 54: 155–167, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall W. Distinguishing theoretical synaptic potentials computed for different soma-dendritic distributions of synaptic input. J Neurophysiol 30: 1138–1168, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remmers JE, Bartlett D. Reflex control of expiratory airflow and duration. J Appl Physiol 42: 80–87, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter DW. Generation and maintenance of the respiratory rhythm. J Exp Biol 100: 93–107, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Road JD, Ford TW, Kirkwood PA. Connections between expiratory bulbospinal neurons and expiratory motoneurons in thoracic and upper lumbar segments of the spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 109: 1837–1851, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Uchino H, Uchino Y. Axon branching of medullary expiratory neurons in the lumbar and sacral spinal cord of the cat. Brain Res 648: 229–238, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saywell SA, Anissimova NP, Ford TW, Meehan CF, Kirkwood PA. The respiratory drive to thoracic motoneurones in the cat and its relation to the connections from expiratory bulbospinal neurones. J Physiol 579: 765–782, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saywell SA, Ford TW, Meehan CF, Todd AJ, Kirkwood PA. Electrical and morphological characterization of propriospinal interneurons in the thoracic spinal cord. J Neurophysiol 105: 806–826, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid K, Kirkwood PA, Munson JB, Shen E, Sears TA. Contralateral projections of thoracic respiratory interneurones in the cat. J Physiol 461: 647–665, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears TA. The fibre calibre spectra of sensory and motor fibres in the intercostal nerves of the cat. J Physiol 172: 150–160, 1964a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]