Abstract

Anatomical studies demonstrate selective compartmental innervation of most human extraocular muscles (EOMs), suggesting the potential for differential compartmental control. This was supported by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrating differential lateral rectus (LR) compartmental contraction during ocular counterrolling, differential medial rectus (MR) compartmental contraction during asymmetric convergence, and differential LR, inferior rectus (IR), and superior oblique (SO) compartmental contraction during vertical vergence. To ascertain possible differential compartmental EOM contraction during vertical ductions, surface coil MRI was performed over a range of target-controlled vertical gaze positions in 25 orbits of 13 normal volunteers. Cross-sectional areas and partial volumes of EOMs were analyzed in contiguous, quasi-coronal 2-mm image planes spanning origins to globe equator to determine morphometric features correlating best with contractility. Confirming and extending prior findings for horizontal EOMs during horizontal ductions, the percent change in posterior partial volume (PPV) of vertical EOMs from 8 to 14 mm posterior to the globe correlated best with vertical duction. EOMs were then divided into equal transverse compartments to evaluate the effect of vertical gaze on changes in PPV. Differential contractile changes were detected in the two compartments of the same EOM during infraduction for the IR medial vs. lateral (+4.4%, P = 0.03), LR inferior vs. superior (+4.0%, P = 0.0002), MR superior vs. inferior (−6.0%, P = 0.001), and SO lateral vs. medial (+9.7%, P = 0.007) compartments, with no differential contractile changes in the superior rectus. These findings suggest that differential compartmental activity occurs during normal vertical ductions. Thus all EOMs may contribute to cyclovertical actions.

Keywords: eye movement, extraocular muscle, magnetic resonance imaging, vertical duction

recent orbital histological studies of intramuscular innervation have suggested the existence of distinct intramuscular arborizations for the medial rectus (MR), lateral rectus (LR), inferior rectus (IR), superior oblique (SO), and inferior oblique (IO) extraocular muscles (EOMs) (da Silva Costa et al. 2011; Le et al. 2014, 2015; Peng et al. 2010). For the horizontal EOMs, the motor nerves are segregated into superior and inferior neuromuscular divisions whose terminal arborizations have minimal overlap (da Silva Costa et al. 2011; Peng et al. 2010). The majority of EOM fibers within the IR are innervated by a single nerve branch, but a secondary nerve branch selectively innervates the lateral third of the IR belly (da Silva Costa et al. 2011), creating potential for selective innervation of the medial (IRm) and lateral (IRl) portions of the IR. Similar to the horizontal EOMs, the trochlear nerve bifurcates prior to entry into the SO and the distal branch of the oculomotor nerve bifurcates prior to entry into the IO (Le et al. 2014, 2015). This nonoverlapping, split innervation occurs in both oblique EOMs. Only the superior rectus (SR) has intermingled, nonsegregated innervation (da Silva Costa et al. 2011).

The parallel organization of individual EOM fibers permits minimal mechanical interaction between adjacent compartments (Lim et al. 2007), potentially endowing them with independent mechanical properties. Both passive and active stimulation of bovine EOMs support mechanical independence of muscle fibers within an EOM: passive tensile loading reveals that only 5% of the mechanical load upon one-half of the EOM tendon is reflected in the other, unloaded half (Shin et al. 2012); furthermore, active contraction by calcium depolarization demonstrates that 90% of the contractile force is confined exclusively to the compartment exposed to a calcium solution (Shin et al. 2015). The width of human EOM tendons allows the parallel EOM fibers to attach at substantially separate scleral sites (Apt 1980; Apt and Call 1982; Demer 2009), potentially endowing the different poles of each compartmentalized EOM with unique oculorotary functions.

The anatomy of SO compartments helps to define their differing mechanical actions. Dissections in human orbits reveal that the medial SO (SOm) fibers insert near the equator of the globe, generating predominantly torsional rotation in central gaze, and the lateral SO (SOl) fibers insert posterior to the equator, generating predominantly vertical rotation in central gaze (Le et al. 2015). The different mechanical advantages of the different sites of scleral attachment, in the context of two distinct trochlear nerve branches, provide a mechanism for differential neural control of torsional and vertical forces within the same EOM. This pattern of control is anatomically feasible for five of the six EOMs, so that there exists a potential for 11 distinct neuromuscular compartments within each orbit.

Direct, in vivo measurement of EOM compartmental tension would require invasive instrumentation with direct visualization of the EOM belly to ensure proper placement of force sensors for each compartment. Such direct techniques have not yet been developed. Alternatively, noninvasive techniques are available to image and measure morphological changes in the EOM belly as indicia of contractility (Demer et al. 1994, 2003; Demer and Miller 1995; Miller 1989). Stereotypically, a contracting EOM exhibits an increase in maximum cross-sectional area and a shift of volume posteriorly, while a relaxing EOM exhibits a decrease in maximum cross-sectional area and a shift of volume anteriorly. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study changes in horizontal EOM morphology during changes in horizontal gaze, we found that the relative change in the posterior partial volume (PPV) of the EOM in the region from 8 to 14 mm posterior to the globe was best correlated with duction among a wide range of measures evaluated (Clark and Demer 2012b). Using change in PPV as the measure of contractility, differential compartmental activity has been demonstrated for the LR during ocular counterrolling (Clark and Demer 2012a), for the MR during asymmetric convergence (Demer and Clark 2014), and for the LR, IR, and SO during vertical fusional vergence (Demer and Clark 2015).

The appropriate MRI indicator for cyclovertical EOM contraction has yet to be established for vertical gaze shifts, so it is unclear whether relative change in PPV is an appropriate functional cyclovertical metric. In addition, all compartmental EOM activity demonstrated to this point has involved special physiological behaviors, i.e., ocular counterrolling to 90° static head tilt, asymmetric convergence, or vertical fusional vergence in response to an artificially induced image disparity. This study had two aims: 1) to determine the MRI morphometric indicator that correlates best with vertical duction and thus best reflects vertical EOM contractility and 2) to apply that measure to determine whether differential EOM compartmental contraction occurs during normal vertical duction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of California, Los Angeles and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. Thirteen normal compensated volunteers [mean age 21.0 ± 2.3 yr (SD), range 18–27 yr] were recruited by local advertisements and then examined by an ophthalmologist-author to verify normal ocular versions, normal distance and near ocular alignment, normal corrected visual acuity, and normal crossed polarization stereopsis of at least 40 arcsec measured at near (Titmus stereoacuity).

Magnetic resonance imaging.

With a 1.5-T General Electric Signa (Milwaukee, WI) scanner equipped with a surface coil array (Medical Advances, Milwaukee, WI), imaging was obtained with a T2 fast spin echo protocol and previously described techniques (Clark and Demer 2012a, 2012b; Demer and Clark 2014, 2015; Demer and Dusyanth 2011). A low-resolution triplanar scan was initially obtained to guide subsequent imaging. For each viewing condition, 18 contiguous 2-mm-thick quasi-coronal image slices were obtained perpendicular to the long axis of each orbit (256 × 256 matrix, 8-cm field of view, 312 μm in-plane resolution; Fig. 1). Scan duration for each set of images was ∼2.5 min, with subjects given hearing protection and a rest period between changes in viewing conditions, for a total experiment duration, including rest periods, of 60–75 min per subject.

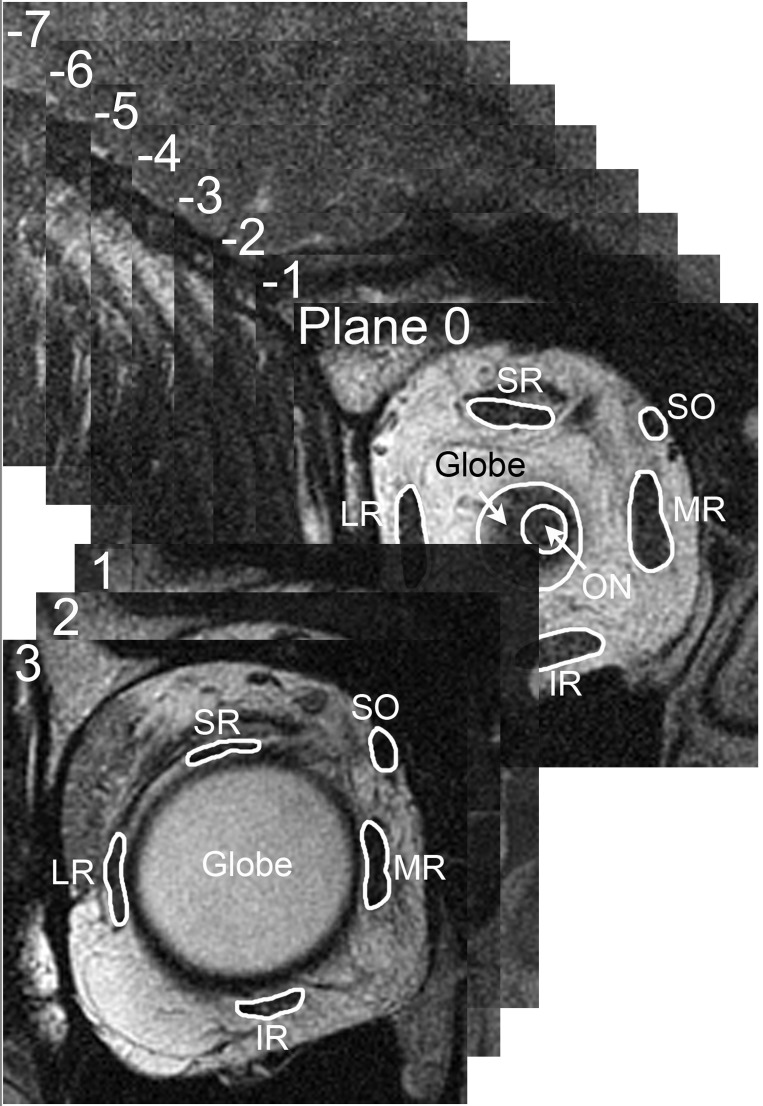

Fig. 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 2-mm-thick quasi-coronal image slices perpendicular to the long axis of each orbit. The image plane containing the globe-optic nerve junction was defined as plane 0, and other image planes were referenced as positive (anterior) or negative (posterior) to this image plane. Within each image plane, each extraocular muscle was manually outlined, with contours omitting adjacent structures. SR, superior rectus; SO, superior oblique; LR, lateral rectus; MR, medial rectus; IR, inferior rectus; ON, optic nerve.

Viewing conditions.

Scans were obtained in the supine position with the head immobilized by foam cushions. Fixation was controlled with blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs) illuminating the ends of optical fibers embedded into a transparent plate affixed to the surface coil array. An illuminated fiber <25 mm directly in front of each eye separately provided an afocal target that was fixated during a reference MRI scan for that orbit. In subsequent scans for each eye, the illuminated fiber target was placed at one of several vertical eccentricities, designated during scanning as low, medium, or maximal supraduction or infraduction for each orbit. Actual angles of duction were computed post hoc from analysis of images. In all, 25 orbits were imaged in 119 fixation conditions from 28.0° supraduction to 30.2° infraduction. Fixations that deviated >10° horizontally from the reference position were excluded (although such deviations averaged <2.5°), as well as image sets compromised by motion or other artifacts preventing reliable outlining of EOM bellies. Fixations with vertical duction were then compared with the 25 central reference conditions, resulting in 93 vertically eccentric image sets (47 infraduction and 46 supraduction), corresponding to an average of about four fixations in infraduction or supraduction for each orbit.

Analysis.

Sets of digital MRI images were converted into stacks and manipulated within ImageJ64 (W. Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 1997–2009; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) and then analyzed with custom software written in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, 2011). Images of left orbits were digitally reflected to the configuration of right orbits. The image plane containing the junction between the optic nerve and the globe was designated as plane 0, and all image planes were referenced as multiples of the 2-mm slice thickness anterior (positive) and posterior (negative) relative to this plane (Fig. 1). Vertical and horizontal eye positions in each viewing condition were determined by the change in positions of the optic nerve centroid and the bony orbital centroid in plane 0, relative to the central gaze reference scan (Clark et al. 1997). Beginning at the most posterior available image plane where individual EOM bellies could be distinguished, the region of each EOM was manually cropped in ImageJ64 into a tagged image file format (TIFF) file containing only the EOM belly without adjacent structures (Clark and Demer 2012a, 2012b).

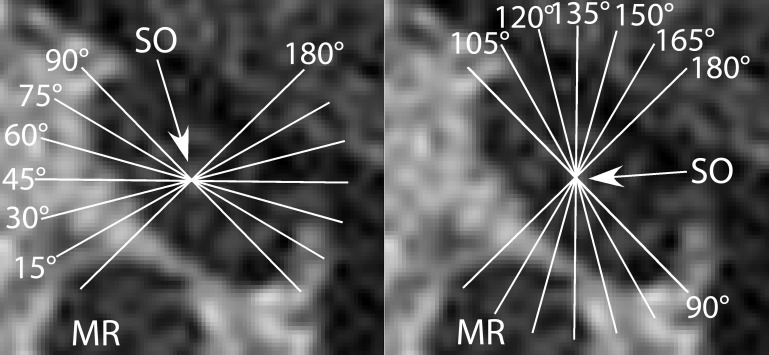

Subsequent analysis was automated. Custom software in MATLAB counted all pixels within each EOM contour and converted them into calibrated cross-sectional area (mm2). Segmentation into provisional compartments was automated following standard orientation of cross sections. The angle of a best-fit line through the maximum transverse EOM dimension relative to scanner vertical was computed for horizontal rectus EOMs and that relative to scanner horizontal for vertical rectus EOMs (Clark and Demer 2012a, 2012b). Each EOM contour was then rotated to align that best-fit line with scanner vertical for horizontal EOMs and to scanner horizontal for vertical EOMs (Clark and Demer 2012a). Cross-sectional areas of the superior and inferior horizontal rectus compartments were calculated above and below the perpendicular bisector of the vertical best-fit line, omitting the central 20% to allow for anatomical variation and possible overlap in central EOM innervation (Clark and Demer 2012a). Similarly, cross-sectional areas of the medial and lateral vertical rectus compartments were calculated relative to the perpendicular bisector of the horizontal best-fit line (Clark and Demer 2012a), again omitting the central 20% because of potential anatomic variation in compartments. For the IR, an alternative analysis technique might have been to bisect the muscle asymmetrically offset laterally to correspond to the histological findings demonstrating asymmetric innervation in a limited sample of subjects. Using a central bisector, however, allowed sufficient residual IR cross section in each compartment to permit analysis and would only decrease, not enhance, the possibility of finding asymmetric compartmental behavior. Finally, because the orientation of SO compartments varies on postmortem histology (Le et al. 2014), the orientation of the putative SO intercompartmental border was determined by a bootstrap technique that evaluated the putative border orientation in 15° increments between 15° and 180° from the major axis of the best-fitting ellipse to the SO cross section (Fig. 2). Function in putative SOm and SOl compartments was computed for all such angular orientations of the border, again omitting the central 20% to account for possible irregularity and overlap of the border. The orientation providing the greatest differential function was considered to be the most likely orientation of the average SO compartmental border (Demer and Clark 2015).

Fig. 2.

The orientation of the putative intercompartmental border within the SO muscle was rotated in 15° increments, with 90° corresponding to the long axis and 180° corresponding to the short axis of the muscle, to generate putative medial and lateral compartments. A bootstrap analysis was then performed to determine the most likely intercompartmental border. The arrow indicates the SO center.

Correlation of changes in EOM morphometry with duction.

A prior study correlating changes in horizontal EOM morphology with changes in horizontal gaze position found that the percent change in PPV spanning four image planes from 8 to 14 mm posterior to the globe-optic nerve junction was best correlated with the action of the muscle (Clark and Demer 2012b). The best correlation from any single plane was found to be the percent change in maximum cross-sectional area (Clark and Demer 2012b). The earlier study was limited, however, because images were not acquired over the entire length of each EOM (Clark and Demer 2012b). Since in that study there was a trend toward increasing correlation when larger partial volumes were included, the present study included more posterior image planes to evaluate more extensive EOM partial volumes with the expectation that this might demonstrate improved correlation with duction. As in the prior study, partial EOM volumes were calculated by multiplying the total EOM cross-sectional area by the 2-mm slice thickness and then summing contiguous volumes from adjacent image slices to create a partial EOM volume over the region of interest (Clark and Demer 2012b).

The present study included images 22 mm posterior to the globe-optic nerve junction (11 image planes posterior to plane 0) and PPVs encompassing different and larger regions of each EOM, while retaining the single-plane and multiplane measures that provided the best correlation from the prior study of horizontal duction (Table 1) (Clark and Demer 2012b). Each measurement was correlated with duction angle, with positive defined as globe rotation into an EOM's field of contraction and negative as the opposite direction. Thus supraduction was defined as positive and infraduction negative for the SR, while supraduction was negative and infraduction positive for the IR. Because supraduction and infraduction are perpendicular to the fields of action of the horizontal EOMs, infraduction was arbitrarily defined as positive when correlating horizontal EOM behavior with vertical duction.

Table 1.

Correlations of EOM morphometry with vertical duction

| Correlation Coefficients R2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR | LR | SR | IR | SO | |

| Single-plane measures | |||||

| Cross-sectional area | |||||

| Change in max area | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.47 |

| Movement of max plane | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.39 |

| Multiplane measures | |||||

| Posterior partial volume | |||||

| Far posterior (planes −11 to −8) | 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.71 | |

| Posterior (planes −7 to −4) | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.55 |

| Anterior (planes −3 to 0) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.14 |

| All (planes −11 to 0) | 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.82 | 0.89 | |

| Posterior half (planes −11 to −6) | 0.003 | 0.15 | 0.76 | 0.87 | |

| Anterior half (planes −5 to 0) | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.66 | 0.25 | |

| SO posterior half (planes −7 to −2) | 0.35* | ||||

Movement of max plane is the anteroposterior shift of the image plane containing the maximum extraocular muscle (EOM) cross section. Posterior partial volumes (PPVs) were calculated from contiguous groups of 4 image planes encompassing anterior, posterior, and far posterior regions of the orbit, a group of all 12 image planes, and 2 groups containing the 6 posterior and 6 anterior image planes. Correlation coefficients of ≥0.2 were significantly correlated with vertical duction angle (P < 0.05). The measure with the highest correlation coefficient for each vertical rectus EOM is highlighted in bold. In most subjects, the superior oblique (SO) was identifiable most posteriorly in image plane −7, so more posterior measurements were not possible.

SO planes −7 to −2 were used for this measure to incorporate more of the posterior SO belly.

MR, medial rectus; LR, lateral rectus; SR, superior rectus; IR, inferior rectus.

Compartmental contractility analysis.

Once the above analysis was completed for the entire EOM cross section, the strongest correlate for vertical duction was used for subsequent compartmental comparisons. Relative changes from central gaze in the anatomically defined superior and inferior MR (MRs and MRi) and LR (LRs and LRi) compartments and IRm and IRl and SOm and SOl compartments were compared by paired t-tests. For completeness, putative medial and lateral SR regions (SRm and SRl) were also compared, even though anatomical studies have not identified segregated, compartmental innervation for the SR.

RESULTS

Changes in EOM morphology.

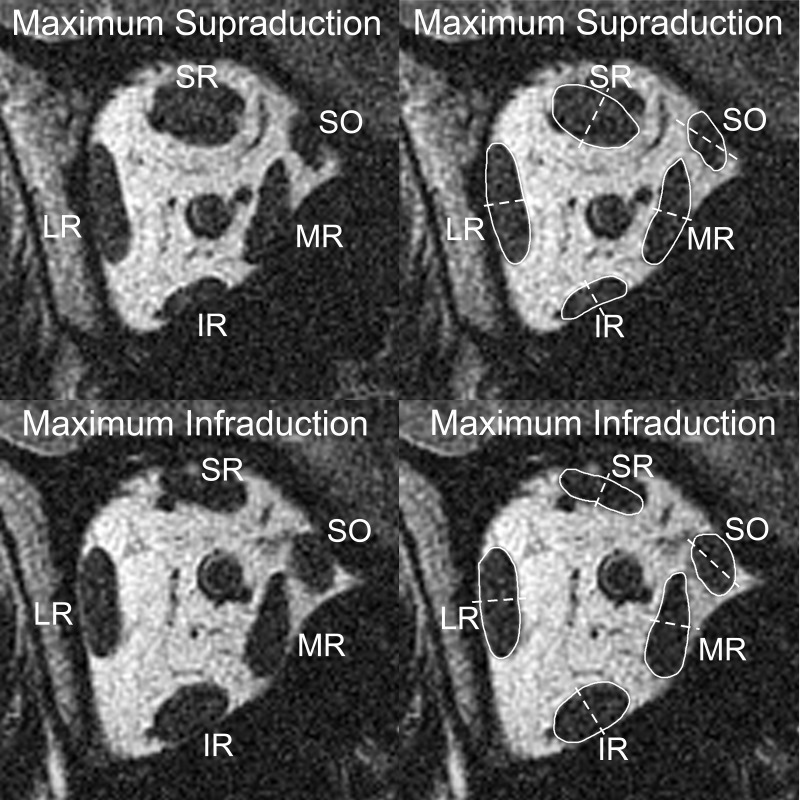

MRI in midorbit demonstrated obvious changes in whole EOM cross sections of the vertical EOMS during vertical gaze shifts (Fig. 3). IR cross-sectional area increased during infraduction and decreased during supraduction. Likewise, SR cross-sectional area increased during supraduction and decreased during infraduction, while the overall cross-sectional areas of the horizontal EOMs remained largely unchanged during either supraduction or infraduction.

Fig. 3.

MRI at plane −5 (10 mm posterior to the globe-optic nerve junction) in maximum supraduction (top) and maximum infraduction (bottom). Images on right are duplicates with the extraocular muscle bellies outlined in white and compartmental bisections marked with dashed white lines. From maximum supraduction to maximum infraduction, the medial half of the IR belly exhibited a larger increase in cross section than the lateral half. Likewise, the superior and inferior halves of the MR belly and the medial and lateral halves of the tilted SO belly demonstrate asymmetric morphological changes.

Best correlation with changes in EOM morphology.

For 93 image sets, any morphometric measure whose correlation for linear regression against vertical gaze position exceeded R2 = 0.20 was judged to be statistically correlated with duction angle (P < 0.05). For the MR and LR, no whole-EOM single-plane or multiplane measure correlated significantly with vertical duction (Table 1), as classically anticipated for horizontal EOMs. To evaluate possible systematic variation in MR and LR morphology due to slight, unintended changes in horizontal eye position during vertical gaze changes, all morphometric measures were checked for correlation with the (<10°) unintended changes of horizontal gaze that were frequently present, but no significant correlations were detected.

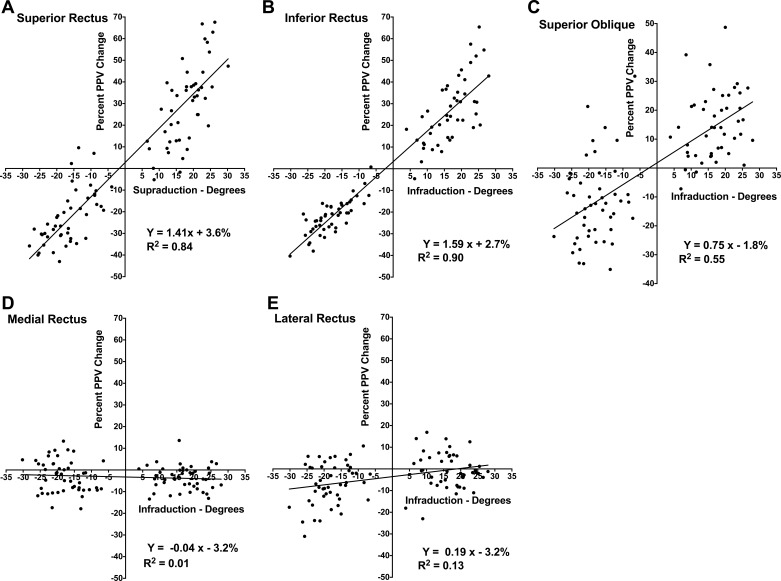

In contrast to the horizontal EOMs, for the SR, IR, and SO almost every single-plane measure and PPV multiplane measure correlated significantly with vertical duction (Table 1). Even though the PPVs that included larger and more posterior regions of the EOM correlated strongly with vertical duction, the measure with the largest correlation coefficient for all vertical EOMs was the percent change in PPV from central gaze for planes −4 to −7 (8–14 mm posterior to the globe-optic nerve junction): R2 = 0.84 for the SR, 0.90 for the IR, and 0.55 for the SO (Fig. 4). Analyzing supraduction and infraduction separately, the PPV was statistically significantly (P < 0.05) correlated with duction for all vertical EOMs in infraduction and for all but the SO in supraduction, where no morphometric measure demonstrated a significant correlation.

Fig. 4.

Percent change in posterior partial volume (PPV) vs. vertical duction for the whole SR (A), IR (B), SO (C), MR (D), and LR (E) muscles with positive duction toward the field of contraction for vertical rectus and toward infraduction for horizontal rectus muscles.

EOM compartmental contractility.

Findings for all EOMs are summarized in Table 2. After the foregoing validation, change in PPV was used as the functional measure for analysis of compartmental behavior. For the IR, pooling all infraduction fixations that together averaged 16.8 ± 6.1°, IRm exhibited a 30.0 ± 2.6% increase in PPV, significantly greater than IRl at 25.6 ± 2.4% (P = 0.03). For the IR, pooling all supraduction fixations that together averaged 18.0 ± 5.4°, IRm relaxed by 20.6 ± 1.5%, not significantly different from IRm at 20.2 ± 1.4% (P = 0.79). Considering only the differences between maximum supraduction and infraduction averaging 42.0 ± 5.1°, the compartmental difference in PPV for IRm was 62.2 ± 3.4%, significantly greater than the mean of 54.9 ± 3.2% for IRl (P = 0.002) with asymmetric contractility in the IR belly apparent even in individual image planes (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Average percent changes in compartmental posterior partial volumes during vertical duction

| All Infraduction Gaze Positions | All Supraduction Gaze Positions | Change with Only Maximum Ductions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRm | +30.0%* | −20.6% | +62.2%* |

| IRl | +25.6% | −20.2% | +54.9% |

| MRs | −8.3%* | +1.9% | −11.7%* |

| MRi | −2.3% | −3.8%* | +1.7% |

| LRs | −2.8%* | −6.8% | +10.2% |

| LRi | +1.2% | −5.7% | +10.8% |

| SOm | +14.5% | −9.2% | +33.7% |

| SOl | +24.2%* | −12.8% | +43.1%* |

| SRm | −22.6% | +29.1% | +61.2% |

| SRl | −25.1% | +27.1% | +64.5% |

IRm, IRl, medial and lateral IR compartments; MRs, MRi, superior and inferior MR compartments; LRs, LRi, superior and inferior LR compartments; SOm, SOl, medial and lateral SO compartments; SRm, SRl, medial and lateral SR regions.

Positive values are toward the field of action of the vertical EOMs or toward infraduction for horizontal EOMs. Bold values represent significantly different percent changes between compartments by paired t-tests, with the larger change in compartmental PPV labeled with an asterisk.

Unlike whole-EOM metrics, differential compartmental changes were present in the MR. There was an average 8.3 ± 1.6% decrease in PPV of MRs averaged over all infraducted positions, yet only a 2.3 ± 0.9% decrease for MRi (P = 0.001). Pooling all supraducted fixations, there was a 1.9 ± 1.8% increase in PPV of MRs but a 3.8 ± 1.3% decrease in MRi (P = 0.02). Considering only maximum infraduction and maximum supraduction, the PPV of MRs was 11.7 ± 2.4% less in infraduction than in supraduction, while the PPV of MRi was 1.7 ± 2.4% greater (P = 0.00005; Fig. 3), a large asymmetry in MR compartmental behavior inconsistent with passive changes to the EOM belly.

Differential compartmental changes were also evident in the LR. Averaging over all infraduction fixations, there was a 1.2 ± 1.2% increase in PPV of LRi in infraduction but a corresponding 2.8 ± 1.5% decrease for LRs (P = 0.0002). However, both LR compartments exhibited similar decreases in PPV averaging over all supraduction fixations (5.7 ± 1.5% LRi vs. 6.8 ± 1.7% LRs, P = 0.36). Comparing only maximum infraduction with maximum supraduction, PPV increased 10.2 ± 2.4% in LRs, similar to 10.8 ± 2.2% in LRi (P = 0.75).

The absence of significant differential compartmental contractility in the LR during supraduction, and from maximum supraduction to maximum infraduction, suggests that the LR may exhibit differential compartmental behavior principally for smaller infraduction angles. A subgroup analysis for the 12 viewing conditions exhibiting the least infraduction (average 8.7 ± 2.2°) revealed a 1.4 ± 3.5% increase in PPV for LRi and a 2.7 ± 3.7% decrease for LRs, a pattern identical to that observed when averaging all viewing infraduction fixations (1.4% LRi increase vs. 2.7% LRs decrease, P = 0.01). This finding is consistent with the presence of the majority of compartmentally asymmetric LRi contractility during initial infraduction from central gaze.

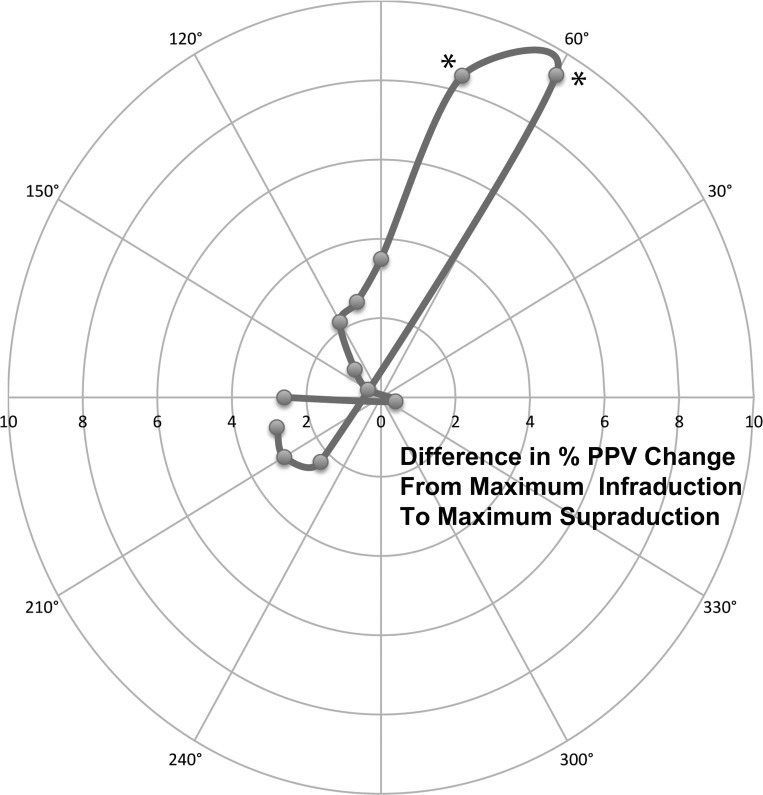

There also was asymmetric differential contractility in SOm vs. SOl between infraduction and supraduction (Fig. 3). The bootstrap analysis comparing differences in putative SO compartments from maximum infraduction to maximum supraduction indicated a clear peak in differential SOm vs. SOl behavior for a 60° intercompartmental demarcation line (Fig. 5), so that bisector was used for all subsequent contractility analysis. Averaging over all infraduction fixations, there was a 24.2 ± 3.2% increase in PPV of SOl, significantly more than the 14.5 ± 2.5% observed for SOm (P = 0.007). Averaging over all supraduction fixations, relaxation in SOl of 12.8 ± 2.7% was similar to relaxation in SOm at 9.2 ± 3.0% (P = 0.22). Considering only maximum infraduction and maximum supraduction, the difference in PPV between SOl and SOm was similar to that found in infraduction only (+43.1 ± 5.2% SOl vs. +33.7 ± 3.7% SOm, P = 0.02), implying that the differential behavior occurred primarily during infraduction.

Fig. 5.

Polar plot of the difference in % PPV change from maximum infraduction to maximum supraduction for putative medial and lateral SO compartments using angled bisectors as shown in Fig. 2. The largest intercompartmental difference was at 60°. Both 60° and 75° (asterisks) demonstrated significant compartmental differences (P = 0.02 for both angled bisectors).

For the SR, there were no significant differences in PPV changes between SRm and SRl for all supraduction (29.1 ± 2.9% vs. 27.1 ± 3.1%, P = 0.32) and infraduction (−22.6 ± 2.2% vs. −25.1 ± 1.9%, P = 0.11) fixations, as anticipated given the histological evidence against differential compartmental innervation. Correspondingly, there were no significant differences comparing putative SR compartments from maximum supraduction to maximum infraduction (61.2 ± 3.3% vs. 64.5 ± 3.6%, P = 0.21).

DISCUSSION

Morphometrics for EOM function.

These results confirm and extend to the vertical rectus and SO EOMs the finding in horizontal EOMs (Clark and Demer 2012b) that MRI morphometric indexes are reliable measures of contractility. Although measures of maximal change in cross section are useful, the most robust measure is the PPV in the region 8–14 mm posterior to the globe-optic nerve junction (Clark and Demer 2012b). While change in duction angle accounts for 95% of change in PPV in groups of subjects and in individual subjects >97% for LR and MR, change in vertical duction angle for cyclovertical EOMs accounts for less PPV variance for whole EOMs in groups of subjects: 90% for IR, 84% for SR, and 55% for SO. These correlations are sufficiently high to be useful as functional measures of EOM contractility. However, even if one accepts the reasonable proposition that change in PPV is a direct measure of EOM function, the correlations for individual cyclovertical EOMs should be expected to be lower for vertical duction than the correlations of horizontal EOM PPV with horizontal duction. While only the LR and MR agonist-antagonist pair contributes significantly to horizontal duction, all cyclovertical EOMs do so for vertical duction, and the present findings show that LR and MR contribute slightly as well. The present findings also confirm and extend to vertical duction the prior demonstrations of differential compartmental contractility, specifically in the rectus and SO EOMs during horizontal convergence (Demer and Clark 2014), vertical vergence (Demer and Clark 2015), and ocular counterrolling (Clark and Demer 2012a). As in prior studies, the transverse borders demarcating the rectus EOM compartments were assumed to lie within the region of their transverse bisectors, ±10% of transverse EOM dimension. This is anatomically consistent with variability in the location of the presumably intercompartmental fissure in LR (Demer and Clark 2014). Thus, in keeping with prior studies, the central 20% of each EOM was excluded from analysis to avoid possible misattribution of compartmental function (Clark and Demer 2012a; Demer and Clark 2014, 2015). Differential contraction in IRm was ∼5% greater than in IRl from central gaze to infraduction, although relaxation in the two compartments was similar in supraduction. Confirming findings of the prior studies and consistent with histological anatomy showing the absence of selective intramuscular innervation (da Silva Costa et al. 2011), SR did not exhibit differential compartmental contractility.

Differential function in horizontal rectus EOMs.

Surprisingly, MR exhibited even greater differential compartmental contractile behavior during vertical duction than IR: while MRs relaxed by 11.7 ± 2.4% from maximal supraduction to infraduction, MRi contracted by 1.7 ± 2.4%. This highly differential behavior in MR, which was confirmed for both supraduction and infraduction, is not likely to be simply due to passive stretching from supraduction to infraduction; any passive effect should cause similar elastic shortening of MRi and elastic stretching of MRs. In addition, this behavior demonstrates that compartments within the same EOM can even act oppositely (contraction and relaxation) simultaneously, instead of just differentials of the same behavior. Moreover, LR exhibited little or no differential compartmental behavior, although it is presumably subject to the same passive mechanical influences as MR. A small differential compartmental difference of ∼4% was observed for LR only from central gaze to small-angle infraduction averaging 8.7°. It is as yet unclear why differential compartmental contraction occurs during normal infraduction, but biomechanically, asymmetric relaxation of the MR and contraction of the LR during infraduction might offset any adducting force created by asymmetric contraction of IRm.

Differential compartmental contraction in superior oblique.

The present study confirms and extends the utility of a bootstrap determination of the intercompartmental boundary within the SO that was developed for vertical fusional vergence (Demer and Clark 2015). This approach is necessary because while the human SO is organized into roughly medial and lateral neuromuscular compartments, the SO belly has an oblique orientation that is variable among individual subjects and even between the two orbits of an individual subject. Furthermore, the demarcation is variably oblique even relative to the major axis of the elliptical SO cross section (Le et al. 2015). The bootstrap method empirically determines the angular orientation of the putative intercompartmental boundary that maximizes the functional difference between lateral and medial compartments, again excluding the central 20% of the SO cross section to avoid misattribution due to curvature or other irregularity of the actual anatomic boundary. As seen in Fig. 5, bootstrap analysis yielded a robust orientation of the intercompartmental boundary at 60° to the major axis of the SO (Fig. 2) that is consistent both with anatomic reconstruction in cadavers (Le et al. 2015) and with the prior MRI study of vertical vergence (Demer and Clark 2015). As was demonstrated during vertical fusional vergence, from central gaze to infraduction there was a 24.2 ± 3.2% increase in PPV of SOl, significantly more than the 14.5 ± 2.5% observed for SOm (P = 0.007), while the relaxation of the two SO compartments in supraduction was similar. The asymmetric contribution of differential compartmental contractility only in the field of SO contraction mirrors the asymmetry observed for IRm, which also exhibited differential compartmental contractility only in infraduction. The significantly asymmetric compartmental behavior of the two major infraductors raises an intriguing question about vertical vergence: is the infraduction of a hyperphoric eye during vertical fusional vergence (Demer and Clark 2015) implemented by the same EOM mechanisms as the supraduction of a hypophoric eye? While these two behaviors are typically treated as interchangeable during clinical measurement of vertical strabismus, there is clinical evidence that they are quite different. The amplitude of normal vertical fusional vergence is greater at near than at distance (Bharadwaj et al. 2007; Hara et al. 1998) but may be greatly enhanced to >10° in individuals with longstanding vertical imbalances, prototypically congenital SO palsy (Kono et al. 2002; Rutstein and Corliss 1995; von Noorden 1996). This adaptation is directionally asymmetric; even slight reversal of such chronic hypertropia by prisms or strabismus surgery produces severe diplopia. The present findings suggest that differential compartmental mechanisms can lower a hypertropic eye but cannot elevate a hypotropic eye. Thus pathological adaptations to hypertropia may be eye specific, with different compensatory mechanisms utilized by hypotropic vs. hypertropic eyes.

Tendon fibers in SOl insert predominantly posterior to the globe equator, and hence have mechanical advantage for infraduction, while tendon fibers of SOm insert more anteriorly near the globe equator, and hence have mechanical advantage in central gaze for incycloduction (Le et al. 2015). This anatomy is consistent with the present finding of greater increase in PPV in SOl than in SOm in infraduction, which would favor infraduction by SOl. However, significant contractility in SOm would also implement incycloduction, perhaps necessary to counteract torsional effects of differential compartmental activity in MR and IR.

Correlation with neuroanatomy.

The differential compartmental function in EOMs observed here during vertical duction is consistent with known intramuscular anatomy. Compartmentally selective innervation has been demonstrated in humans, monkeys, and other mammals for the IR (da Silva Costa et al. 2011), LR (da Silva Costa et al. 2011; Peng et al. 2010), MR (da Silva Costa et al. 2011), and SO (Le et al. 2014), but innervation is not compartmentally selective in the SR (da Silva Costa et al. 2011), where no functional study has found evidence of differential compartmental contractility. In those EOMs where peripheral neuroanatomy would permit differential compartmental function, differential function occurs only in some EOMs for particular ocular motor behaviors. During horizontal convergence, MRs makes a major contribution (Demer and Clark 2014). During vertical fusional vergence requiring infraduction of one eye, major differential compartmental contributions are made by LRs, ipsilateral SOm, and contralateral SOl but not MR or IR. During ocular counterrolling, LRi makes a major contribution but not MR or IR. These differences emphasize that the capability to generate differential compartmental behavior in EOMs does not obligate the ocular motor system to employ this behavior at all times but rather only in physiologically advantageous circumstances. This is analogous to a musical ensemble that can play either in unison or in various patterns of harmony.

Pathology of vertical ocular duction, due to motor neuropathy or EOM myopathy, may cause vertical strabismus and vertical diplopia. There is clinical evidence that many cases of SO palsy may selectively involve only the medial or lateral compartment, sparing the other compartment (Shin and Demer 2015). Isotropic SO atrophy, interpreted as involving both SO compartments, compromises infraduction in adduction more than anisotropic atrophy, which is interpreted as involving only one SO compartment (Shin and Demer 2015). This may be analogous to selective palsy of LRs (Clark and Demer 2014), which is associated with vertical strabismus, usually ipsilesional hypotropia (Pihlblad and Demer 2014).

Differential compartmental activity in MR during vertical duction implies a contribution of vertical premotor inputs to the MR subnuclei in the midbrain. In the caudal midbrain, the MR is innervated by the ventrally located A and dorsolaterally located B subgroups that are separated by the SR, IR, and IO motoneuron pools within the nucleus. The C group located outside the border of the oculomotor nucleus projects to the multiply innervated fibers (Büttner-Ennever 2007; Buttner-Ennever et al. 2002, 2003; Buttner-Ennever and Akert 1981; Buttner-Ennever and Horn 2002). The MR motor nucleus extends more rostrally as a single subnucleus (Ngwa et al. 2014). Earlier studies in cat and monkey suggested that the classic horizontally acting EOMs receive glycinergic inputs (Spencer et al. 1989) but the classically cyclovertical EOMs receive GABAergic inputs (Spencer et al. 1989; Spencer and Baker 1992). However, more recently, it has been reported in monkey that all rectus EOMs receive GAGAergic input while only MR motor neurons receive glycinergic inputs (Zeeh et al. 2015). EOMs classically mediating supraduction receive selective projections from calretinin-positive afferents, while those mediating infraduction do not (Ahlfeld et al. 2011; Zeeh et al. 2013). In the oculomotor nucleus, the classically horizontal and vertical motor pools are in such intimate proximity that they could easily share inputs. It is tempting to speculate that the A and B subnuclei might selectively supply the MRi vs. the MRs. However, anatomical evidence on this question is lacking.

Differential compartmental behavior of SO also invites the speculation that distinct trochlear motor neuron populations might innervate the two compartments for selectively vertical vs. torsional effects. Once again, there is as yet no anatomical evidence on this question. Potential premotor input from the interstitial nucleus of Cajal and rostral interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus appear to contain both vertical and torsional signals (Crawford et al. 1991; Farshadmanesh et al. 2007).

Predictions for ocular motor neuron behavior.

The present findings suggest several predictions for oculomotor neuron behavior testable in behaving primates. First, it is predicted that a population of MR motor neurons, possibly in one subnucleus, will have significant positive correlations with supraduction, but abducens neurons will not have such a subpopulation. Conversely, based on other findings (Demer and Clark 2015), a population of LR motor neurons will show selective sensitivity during vertical vergence. Second, it is predicted that a population of SO motor neurons, presumably innervating SOl, will have significant positive correlations with infraduction, but motor neurons innervating SOm will not. During vertical vergence, however, most trochlear neurons are predicted to have correlations with infraduction and incycloduction, but in varying proportions depending upon compartmental projection.

Recommendations.

Emerging evidence shows that the effectors of eye movements are increasingly complex. Broadly, the present findings showing differential compartmental contributions of MR and SO to vertical duction suggest the general value of three-dimensional monitoring of eye positions when studying the behavior of motor and premotor processing in the ocular motor system.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Eye Institute Grant EY-08313. J. L. Demer was supported by an unrestricted award from Research to Prevent Blindness and holds the Leonard Apt Chair of Pediatric Ophthalmology.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.A.C. and J.L.D. conception and design of research; R.A.C. and J.L.D. analyzed data; R.A.C. and J.L.D. interpreted results of experiments; R.A.C. and J.L.D. prepared figures; R.A.C. drafted manuscript; R.A.C. and J.L.D. edited and revised manuscript; R.A.C. and J.L.D. approved final version of manuscript; J.L.D. performed experiments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Nicolasa de Salles and David Burgess provided technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- Ahlfeld J, Mustari M, Horn AK. Sources of calretinin inputs to motoneurons of extraocular muscles involved in upgaze. Ann NY Acad Sci 1233: 91–99, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apt L. An anatomical reevaluation of rectus muscle insertions. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 78: 365–375, 1980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apt L, Call NB. An anatomical reevaluation of rectus muscle insertions. Ophthalmic Surg 13: 108–112, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj SR, Hoenig MP, Sivaramakrishnan VC, Karthikeyan B, Simonian D, Mau K, Rastani S, Schor CM. Variation of binocular-vertical fusion amplitude with convergence. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 1592–1600, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büttner-Ennever JA. Anatomy of the oculomotor system. Dev Ophthalmol 40: 1–14, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner-Ennever JA, Akert K. Medial rectus subgroups of the oculomotor nucleus and their abducens internuclear input in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 197: 17–27, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner-Ennever JA, Eberhorn A, Horn AK. Motor and sensory innervation of extraocular eye muscles. Ann NY Acad Sci 1004: 40–49, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner-Ennever JA, Horn AK. The neuroanatomical basis of oculomotor disorders: the dual motor control of extraocular muscles and its possible role in proprioception. Curr Opin Neurol 15: 35–43, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttner-Ennever JA, Horn AK, Graf W, Ugolini G. Modern concepts of brainstem anatomy: from extraocular motoneurons to proprioceptive pathways. Ann NY Acad Sci 956: 75–84, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RA, Demer JL. Differential lateral rectus compartmental contraction during ocular counter-rolling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 2887–2896, 2012a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RA, Demer JL. Functional morphometry of horizontal rectus extraocular muscles during ocular duction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 7375–7379, 2012b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RA, Demer JL. Lateral rectus superior compartment palsy. Am J Ophthalmol 15: 479–487, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RA, Miller JM, Demer JL. Location and stability of rectus muscle pulleys: muscle paths as a function of gaze. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38: 227–240, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JD, Cadera W, Vilis T. Generation of torsional and vertical eye position signals by the interstitial nucleus of Cajal. Science 252: 1551–1553, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Costa RM, Kung J, Poukens V, Yoo L, Tyschen L, Demer JL. Intramuscular innervation of primate extraocular muscles: unique compartmentalization in horizontal recti. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52: 2830–2836, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL. Extraocular muscles. In: Duane's Ophthalmology, edited by Jaeger E, Tasman P. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL, Clark RA. Magnetic resonance imaging of differential compartmental function of the horizontal rectus extraocular muscles during conjugate and converged ocular adduction. J Neurophysiol 112: 845–855, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL, Clark RA. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates compartmental muscle mechanisms of human vertical fusional vergence. J Neurophysiol 113: 2150–2163, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL, Dusyanth A. T2 fast spin echo magnetic resonance imaging of extraocular muscles. J AAPOS 15: 17–23, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL, Kono R, Wright W. Magnetic resonance imaging of human extraocular muscles in convergence. J Neurophysiol 90: 2072–2085, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL, Miller JM. Magnetic resonance imaging of the functional anatomy of the superior oblique muscle. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36: 906–913, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer JL, Miller JM, Koo EY, Rosenbaum AL. Quantitative magnetic resonance morphometry of extraocular muscles: a new diagnostic tool in paralytic strabismus. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 31: 177–188, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farshadmanesh F, Klier EM, Chang P, Wang H, Crawford JD. Three-dimensional eye-head coordination after injection of muscimol into the interstitial nucleus of Cajal (INC). J Neurophysiol 97: 2322–2338, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara N, Steffen H, Roberts DC, Zee DS. Effects of horizontal vergence on the motor and sensory components of vertical fusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 39: 2268–2276, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono R, Hasebe S, Ohtsuki H. [Vertical vergence adaptation in cases of superior oblique palsy.] Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi 106: 34–38, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le A, Poukens V, Demer JL. Compartmental innervation scheme for the mammalian superior oblique (SO) and inferior oblique (IO) muscles (Abstract). Soc Neurosci Abstr 62: 22, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Le A, Poukens V, Ying H, Rootman D, Goldberg RA, Demer JL. Compartmental innervation of the superior oblique muscle in mammals. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56: 6237–6246, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KH, Poukens V, Demer JL. Fascicular specialization in human and monkey rectus muscles: evidence for anatomic independence of global and orbital layers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 3089–3097, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JM. Functional anatomy of normal human rectus muscles. Vision Res 29: 223–240, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwa EC, Zeeh C, Messoudi A, Buttner-Ennever J, Horn AK. Delineation of motoneuron subgroups supplying individual eye muscles in the human oculomotor nucleus. Front Neuroanat 8: 2, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng M, Poukens V, da Silva Costa RM, Yoo L, Tyschen L, Demer JL. Compartmentalized innervation of primate lateral rectus muscle. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 51: 4612–4617, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlblad M, Demer JL. Hypertropia in unilateral, isolated abducens palsy. J AAPOS 18: 235–240, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein RP, Corliss DA. The relationship between duration of superior oblique palsy and vertical fusional vergence, cyclodeviation, and diplopia. J Am Optom Assoc 66: 442–448, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin A, Yoo L, Chaudhuri Z, Demer JL. Independent passive mechanical behavior of bovine extraocular muscle compartments. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 8414–8423, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin A, Yoo L, Demer JL. Independent active contraction of bovine extraocular muscle compartments. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56: 199–206, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SY, Demer JL. Superior oblique extraocular muscle shape in superior oblique palsy. Am J Ophthalmol 159: 1169–1179, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RF, Baker R. GABA and glycine as inhibitory neurotransmitters in the vestibulo-ocular reflex. Ann NY Acad Sci 656: 602–611, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RF, Wenthold RJ, Baker R. Evidence for glycine as an inhibitory neurotransmitter of vestibular, reticular, and prepositus hypoglossi neurons that project to the cat abducens nucleus. J Neurosci 9: 2718–2736, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Noorden GK. Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility: Theory and Management of Strabismus. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeh C, Hess BJ, Horn AK. Calretinin inputs are confined to motoneurons for upward eye movements in monkey. J Comp Neurol 521: 3154–3156, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeh C, Mustari MJ, Hess BJ, Horn AK. Transmitter inputs to different motoneuron subgroups in the oculomotor and trochlear nucleus in monkey. Front Neuroanat 9: 95, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]