Abstract

This case study discusses a recent diagnosis of a rare form of ectopic pregnancy within a Caesarean section scar. Evidence indicates that the prevalence of this form of ectopic pregnancy is escalating due to the increasing number of Caesarean sections performed. As ultrasound plays a major role in diagnosing this rare life-threatening condition, we recommend key points for practitioners to consider for meticulous assessment and accurate diagnosis.

Keywords: Ultrasound, endometrial canal, uterine rupture, maternal morbidity, hysterectomy

Introduction

A pregnancy that develops within a Caesarean scar is a very rare form of ectopic pregnancy. The incidence is, however, rising most likely due to the increasing number of Caesarean section deliveries performed and increasing detection rates through improved imaging resolution.1 Undetected Caesarean scar pregnancies are associated with serious maternal morbidities including haemorrhage and emergency hysterectomy. Ultrasound plays a vital role in detecting all types of ectopic pregnancy, and practitioners should be aware of common presentation and ultrasound appearances associated with Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. In the last year, we have detected three cases at our institution. All three women were invited to consent to their cases being presented here. One did not respond and, of the other two, only one was suitable for discussion. We describe her experience and recommend learning points for ultrasound practitioners.

Case report

A 39-year-old Caucasian woman, G6 P3 +2, presented to the accident and emergency department with dark brown vaginal discharge and abdominal pain. She had had a positive pregnancy test following a period of amenorrhoea. On clinical examination, the abdomen was soft and there was no bleeding or pain on speculum inspection. The patient’s case-specific history included three lower segment Caesarean sections, two of which were elective and one was an emergency, and evacuation of retained products of conception. Additionally, there was a long history of endometriosis followed by radiological diagnosis of adenomyosis.

An ultrasound examination, using a Philips iU22 unit (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) with an xMatrix 6-1 MHz and transvaginal 10-3 MHz transducer, was performed. Transabdominally, ultrasound showed a regular endometrium with no evidence of a gestation sac (GS). On further interrogation, a cystic structure with a thick wall was seen in the anterior mid-uterine segment, which gave appearances of a GS with a trophoblastic reaction (Figure 1(a) and (b)). Transvaginally, the fundal endometrium measured 12.6 mm and a live six-week pregnancy was located in the lower uterine segment within the anterior wall, adjacent to a previous Caesarean scar (Figure 2(a) and (b)), thus providing the diagnosis of Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. The patient was referred to a tertiary fetal medicine centre for vaginal surgical treatment. The woman made a full recovery and fertility was preserved. Currently she is pregnant again and expecting her fourth child soon.

Figure 1.

Transabdominal images suggesting a gestation sac of 21.5 mm diameter developing in the anterior uterine wall. Note the apparent trophoblastic reaction in image (a) and the thin endometrium visible in image (b)

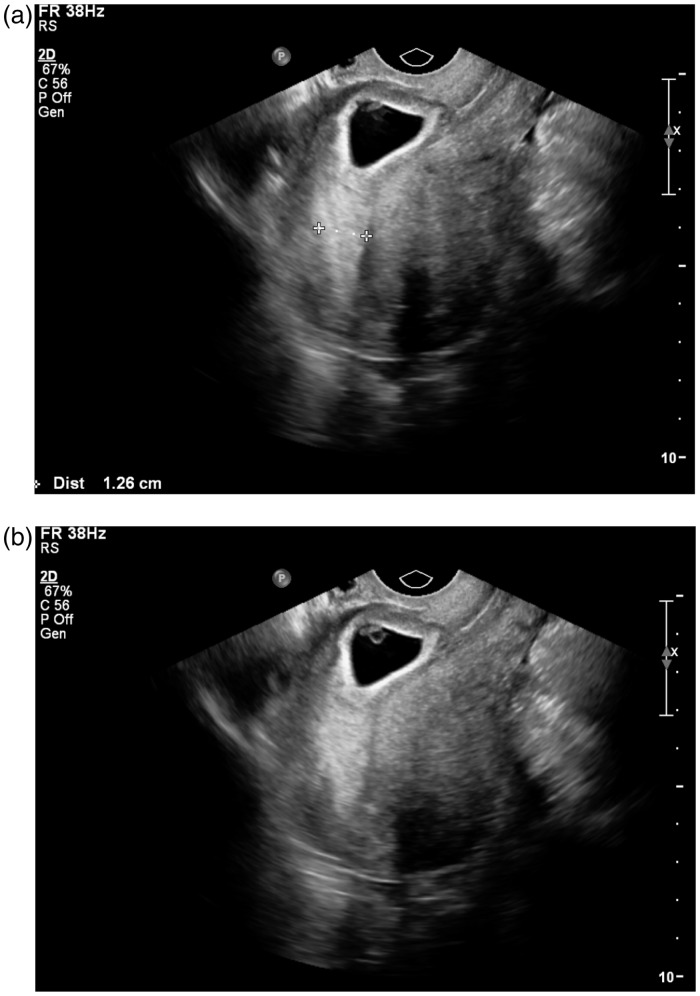

Figure 2.

(a and b) Transvaginal images demonstrating an obvious gestation sac containing yolk sac and embryo. Note the 12 mm endometrium and the relationship of the gestation sac with the uterine cervix and fundus

Discussion

Implantation of the blastocyst and subsequent development of the GS within a previous Caesarean section scar is extremely rare, although some reports suggest incidences of 1 : 1800 to 1 : 2226 pregnancies.2,3 Our experience of three cases in one year at a centre with approximately 5300 deliveries annually, concurs with these estimates. The mechanism behind a scar ectopic is not fully understood but is thought to involve invasion of the blastocyst deep into the myometrium via a microscopic channel between the Caesarean section scar and the endometrial canal.1 The developing pregnancy is then completely surrounded by myometrium and fibrous scar tissue and has no contact with the endometrial cavity.

Risk factors for scar ectopic pregnancy include multiple Caesarean sections,4 although a recent study involving 13 cases of scar ectopic found that the majority (69%, n = 9) had had only one previous section.5 At the time of diagnosis during the first trimester, approximately 30% of women may have no symptoms at all.6 Bleeding and pain, as in our case, are the most common signs at presentation.

Recognition of scar ectopic appearances on ultrasound is essential, since any delay in diagnosis may result in uterine rupture, haemorrhage and subsequent hysterectomy with loss of future fertility. Evidence also suggests that scar ectopic pregnancies, if untreated, may evolve into morbidly adherent placenta.7

Scar ectopic pregnancies may be difficult to detect sonographically, particularly if the pregnancy is early and appearances are subtle. Appearances may, at first glance, mimic that of an imminent miscarriage or of a cervical ectopic pregnancy due to the low position of the GS in relation to the uterus. Careful interrogation, using a high-frequency transvaginal transducer, of the anterior lower uterine wall and identification of the previous scar is required. Meticulous assessment of the endometrium to exclude normal implantation should also be part of a systematic ultrasound examination. Sonographic criteria during evaluation of cases of suspected scar ectopic must include the following:

Diagnosis of an empty uterine cavity

Diagnosis of an empty cervical canal

Development of the sac in the anterior isthmic segment

Circumferential flow using colour Doppler

Absent or diminished myometrial thickness between the sac and maternal bladder.8–10

Colour Doppler can be a useful tool and add information when diagnosing a Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. A live pregnancy would show marked circumferential peritrophoblastic vascularity surrounding the GS.1 Additionally, a normal waveform in early pregnancy demonstrates prominent high velocity with low impedance flow.2 Conversely, a missed miscarriage will show no peritrophoblastic flow. The ‘sliding sign’ is also helpful when trying to differentiate between incomplete miscarriage and cervical ectopic pregnancy.2 By using gentle pressure with the transducer, the GS of an incomplete miscarriage will move whereas cervical and scar ectopic gestations will be fixed. The main criteria are summarised in Table 1. In equivocal cases, laparoscopy or magnetic resonance imaging may increase diagnostic confidence.8

Table 1.

Sonographic criteria for diagnosis of Caesarean section ectopic pregnancy

| Caesarean section ectopic | Cervical ectopic | Missed miscarriage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| History of previous Caesarean section | Yes | N/A – but slight increased risk | N/A |

| Gestation sac location | Anterior lower uterine wall | Endocervical canal | May be in cervical canal |

| Colour Doppler appearances | Circumferential vascularity demonstrated | Circumferential vascularity demonstrated | No vascularity identified |

| Evidence of ‘sliding sign’ | Fixed gestation sac | Fixed gestation sac | Mobility of gestation sac with gentle pressure |

There is no consensus on treatment of scar ectopic pregnancies and it depends, to a degree, on the gestational age. Systemic methotrexate may be successful for treating early gestations although regression can take a long time and there is still the risk of uterine rupture. Furthermore, the minute channel in which the scar ectopic embedded in the first place will still be present and may lead to recurrent scar ectopic pregnancy.11

Curettage is contraindicated because the GS is outside the uterine cavity, and the risk of rupture and haemorrhage is increased.12 Alternatively, transvaginal surgery, as in our case, is an option and allows repair of the uterine defect at the same time. A recent case series describes six patients who were all treated successfully with transvaginal surgery.9 Laparoscopy or laparotomy is another recognised management pathway for scar ectopic, although repairing the uterine defect may be difficult in some cases depending on uterine position.9 A recent report suggests that many clinicians prefer to use a combination of medical and surgical strategies.13

Conclusion

The incidence of scar ectopic pregnancy is rising, and ultrasound practitioners should consider this as a differential diagnosis in women experiencing pain and bleeding in the early stages of pregnancy and who have a history of Caesarean section delivery. Careful transvaginal evaluation of the anterior uterine wall, endometrial cavity and cervical canal will aid diagnostic confidence and expedite appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patient who gave permission to use her case report for this manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval: Not required but written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details and images from the case.

Guarantor: HE

Contributorship: DS compiled the case study and images. HE researched literature and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DS, KH and DW reviewed the first draft of manuscript, and provided additional literature. DS, HE and DW constructed the table. DS and HE reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ash A, Smith A, Maxwell D. Caesarean scar pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 114: 253–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, et al. First trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment caesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seow K, Huang L, Lin Y. Cesarean scar pregnancy: issues in management. Ultrasound Obs Gyn 2004; 23: 247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maymon R, Halperin R, Mendlovic S, et al. Ectopic pregnancies in Caesarean section scars: the 8 year experience of one medical center. Hum Reprod 2004; 19: 278–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michener C, Dickinson J. Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: a single centre case series. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 49: 451–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rotas M, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis and management. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107: 1373–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben Nagi J, Ofili-Yebovi D, Marsh M, et al. First trimester caesarean scar pregnancy evolving into placenta previa/accrete at term. J Ultrasound Med 2005; 24: 1569–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sum T, Wong S, Tai C, et al. An ectopic pregnancy in a previous caesarean section scar: treatment with systemic methotrexate and uterine artery embolisation. J Obstet Gynaecol 2000; 20: 328–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He M, Chen M-H, Xie HZ, et al. Transvaginal removal of ectopic pregnancy tissue and repair of uterine defect for caesarean scar pregnancy. BJOG 2011; 118: 1136–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seow K, Hwang J, Tsai Y. Ultrasound diagnosis of a pregnancy in a Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001; 18: 547–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasegawa J, Ichizuka K, Matsuoka R, et al. Limitations of conservative treatment for repeat Caesarean scar pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005; 25: 310–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang YL, Su TH, Chen HS. Operative laparoscopy for unruptured ectopic pregnancy in a caesarean scar. BJOG 2006; 113: 1035–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta N, Haas B, Ekechukwu K, et al. Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Gynecol Obstet 2013; 2: 42–4. [Google Scholar]