Abstract

Ultrasound is a potential method for assessing muscle size of the extremity and trunk. In a large muscle, however, a single image from portable ultrasound measures only muscle thickness (MT), not anatomical muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) or muscle volume (MV). Thus, it is important to know whether MT is related to anatomical CSA and MV in an individual muscle of the extremity and trunk. In this review, we summarize previously published articles in the lower extremity demonstrating the relationships between ultrasound MT and muscle CSA or MV as measured by magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans. The relationship between MT and isometric and isokinetic joint performance is also reviewed. A linear relationship is observed between MT and muscle CSA or MV in the quadriceps, adductor, tibialis anterior, and triceps surae muscles. Intrarater correlation coefficients range from 0.90 to 0.99, except for one study. It would appear that anterior upper-thigh MT, mid-thigh MT and posterior thigh MT are the best predictors for evaluating adductor, quadriceps, and hamstrings muscle size, respectively. Despite a limited number of studies, anterior as well as posterior lower leg MT appear to reflect muscle CSA and MV of the lower leg muscles. Based on previous studies, ultrasound measured anterior thigh MT may be a valuable predictor of knee extension strength. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to clarify the relationship between lower extremity function and MT.

Keywords: B-mode ultrasound, muscle thickness, muscle CSA and volume

Introduction

Anatomical muscle cross-sectional area (CSA), which is measured in a plane axial to the longitudinal axis of the muscle, and muscle volume (MV) are important physiological variables for evaluating functional capacity of the muscle1–3 and the effectiveness of various physical training programs.4–7 Although muscle force is linearly associated with physiological muscle CSA (i.e. represents the maximal number of acto-myosin cross-bridges), MV as well as anatomical muscle CSA is a valuable predictor of muscular strength and power output.1,8,9 A good evaluation of muscle CSA and MV can be obtained by using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure multiple cross sections of individual muscles of the extremity and trunk. However, MRI is not a widely used technique due to the costs associated with this measurement. Considering clinical and field testing, a sufficiently accurate and widely used method for muscle size assessment is needed.

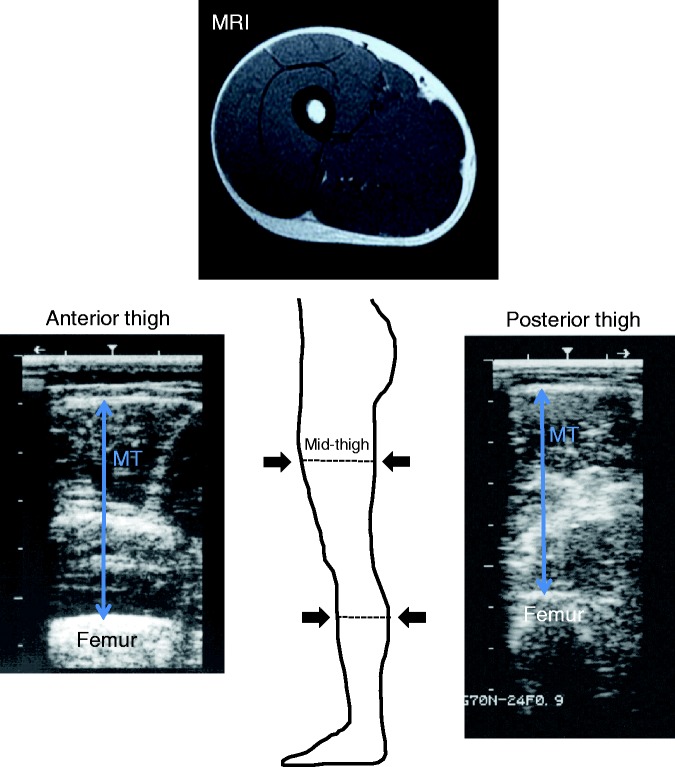

Ultrasound is a non-invasive, quick, low cost, and safe imaging technique that can be easily applied in clinical assessment and field survey. Approximately a half-century ago, Ikai and Fukunaga1 measured muscle CSA of the limb muscle using a special designed ultrasound apparatus. Without a small muscle, however, a single image from a portable ultrasound only measures muscle thickness (MT) (Figure 1), but not muscle CSA and MV. Since muscle CSA and MV are valuable to know, it would be important to examine if MT was related to these variables in the extremity and trunk muscles. Additionally, another interesting point is whether a functional relationship is observed with MT in single and multiple joint muscles of the extremity and trunk. We recently reported the morphological and functional relationships with ultrasound measured MT of the upper extremity and trunk.10 Thus, the purpose of this brief review was threefold. First, we discuss the validity and reliability of MT measurements in the thigh and lower leg muscles. Second, we summarize the previously published articles in the lower extremity demonstrating the relationships between ultrasound measured MT and muscle CSA or MV measured using MRI and computed tomography (CT) scans. Lastly, the relationships between MT and isometric and isokinetic joint performances are summarized.

Figure 1.

Typical ultrasound image showing the transverse scans of the anterior thigh (left) and the posterior thigh (right) at 50% of thigh length.

MT: muscle thickness

In this review, the terms thigh and lower leg were used. The term “lower leg” refers to the section of the lower extremity extending from the knee to the ankle, while the term “thigh” refers to the section between the pelvis and the knee.

Literature search and inclusion criteria

The process of literature search and inclusion criteria was the same as described in the previous study.10 Briefly, a typical online search using CINAHL, MEDLINE, SPORTDiscuss, and Web of Science was performed with the following keywords and phrases to obtain relevant articles: “ultrasound muscle thickness” AND “lower extremity” OR “thigh” OR “leg” AND/OR “muscle CSA” OR “muscle volume” AND/OR “strength” OR “function”. References from pertinent articles and the name of the authors cited were cross-referenced to locate any further relevant articles not found with the initial search. To be included, a study needed to meet the following criteria: (a) Main outcome measure: the study needed to measure muscle thickness of the lower body muscles using a B-mode ultrasound; (b) Secondary outcome measures: the study needed to investigate muscle CSA and/or MV measured by MRI or CT scan, isometric and/or isokinetic muscular strength and/or physical functions; (c) Reliability data: the study needed to report a single intrarater and/or interrater reliability value in the lower extremity muscles but not a range of those values; (d) Language: the search was limited to original research that was written in English. Furthermore, we discuss the validity of ultrasound measurements, including the articles that were not collected by means of the aforesaid online search procedures.

Validity and reliability of MT measurements

Adequate validity and reliability is necessary if ultrasound measurements are to be used as measures of muscle size. Fukunaga et al.11 investigated the validity of ultrasound measurements at the thigh, upper arm, and abdomen using a human cadaver. They reported that the difference between ultrasound and manual measured values was 0.03 (SD 0.02) cm for anterior thigh, 0.05 (SD 0.09) cm for posterior thigh, and 0.04 (SD 0.06) cm for posterior lower leg. Kawakami et al.12 also reported that ultrasound measurements differed from manual measurements by ∼0.1 cm for MT. Thus, precision and linearity of image reconstruction have been confirmed.

Intrarater and interrater reliabilities in the lower extremity muscles are presented in Table 1. Reported estimates of reliability were good to high.13–21 With the exception of a study reported by Thoirs and Englsh,15 the reported intrarater correlation coefficients (ICC) among studies ranged between 0.90 and 0.99. Thoirs and Englsh15 reported that high test-retest reliability was indicated in the lower extremity when subjects were measured in a standing position (ICC, 0.70–0.89; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.79–0.94 for anterior thigh and 0.49–0.84 for posterior thigh, respectively). However, the lowest ICC and 95% CI values (0.34 and 0.07–0.64, respectively) were observed at the posterior lower leg when subjects are measured in a lying position. In that study, the authors noted that the rater found it difficult to visualize the image obtained from the posterior thigh. Compared to other sites, the difficult visualization may be associated with the geometry of the femur, and this may produce larger measurement errors compared to other sites. In addition, alteration in muscle tone between different body positions (standing vs. lying) among individuals may also influence the low reliability in the posterior thigh. Recently, Abe et al.17,22 reported ICC, standard error of measurement (SEM), and minimum difference from 15 middle-aged subjects. Whereas ICC is a relative measure of reliability, the SEM is a measure of absolute reliability. Absolute reliability concerns the consistency of scores of individuals, whereas relative reliability concerns the consistency of the position or rank of individuals in the group relative to others.23 The authors indicated that ICC and SEM were 0.98 and 0.07 cm for anterior thigh and 0.95 and 0.10 cm for posterior thigh (Table 1).

Table 1.

Intrarater and interrater reliability of ultrasound muscle thickness measurements at each measured site

| Measured site | Number of subjects | Posture and state of MT testing | Device | Reliability & Precision |

Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | 95%CI | SEM | ||||||

| Intrarater reliability | ||||||||

| Anterior thigh | N = 10 | Standing | Resting | Aloka | 0.97 | – | – | Miyatani et al. 200413 |

| VL | N = 21 | Sitting | Resting | GE | 0.96 | 0.90–.98 | – | Raj et al. 201214 |

| Anterior thigh | N = 18 | Standing | Resting | Nanshan | 0.89 | 0.79–.94 | – | Thoirs & English 200915 |

| Supine | Resting | 0.90 | 0.80–.95 | – | ||||

| Posterior thigh | N = 18 | Standing | Resting | 0.70 | 0.49–.84 | – | ||

| Prone | Resting | 0.71 | 0.79–.84 | – | ||||

| Anterior thigh | N = 42 | Supine | Resting | NR | 0.98 | – | – | Tillquist et al. 201416 |

| Anterior thigh | N = 15 | Standing | Resting | Aloka | 0.98 | – | 0.07 | Abe et al. 201417 |

| Posterior thigh | 0.95 | – | 0.10 | |||||

| Posterior lower leg | YM = 15 | Prone | Resting | GE | 0.98 | – | – | Weiss & Clark 198518 |

| Posterior lower leg | YW = 15 | Prone | Resting | 0.99 | – | – | ||

| Posterior lower leg | N = 10 | Standing | Resting | Aloka | 0.96 | – | – | Miyatani et al. 200413 |

| Anterior lower leg | N = 18 | Standing | Resting | Nanshan | 0.83 | 0.69–.91 | – | Thoirs & English 200915 |

| Supine | Resting | 0.88 | 0.77–.94 | – | ||||

| Posterior lower leg | N = 18 | Standing | Resting | 0.83 | 0.69–.91 | – | ||

| Prone | Resting | 0.34 | 0.07–.64 | – | ||||

| MG | YC = 21 | Prone | Resting | Phillips | 0.94 | 0.86–.98 | – | Legerlotz et al. 201019 |

| Chison | 0.98 | 0.94–.99 | – | |||||

| MG | N = 21 | Prone | Resting | GE | 0.97 | 0.92–.99 | – | Raj et al. 201214 |

| TA | N = 10 | Supine | Resting | GE | 0.90 | – | – | Crofts et al. 201420 |

| Interrater reliability | ||||||||

| Anterior thigh | N = 78 | Supine | Resting | NR | 0.95 | – | – | Tillquist et al. 201416 |

| MG | N = 15 | Prone | Resting | GE | 0.82 | – | 0.1 | Konig et al. 201421 |

YM, young men; YW, young women; YC, young children; VL, vastus lateralis; MG, gastrocnemius medialis; TA, tibialis anterior

ICC, intra- or inter-class correlation coefficient; CI, confidence interval; SEM, standard error of measurement; NR, not reported

Two studies16,21 reported interrater reliability in the lower extremity muscles and the values demonstrated high reliability (ICC, 0.82 and 0.95). Furthermore, a study19 investigated inter-machine reliability of different ultrasound machines and found that inter-machine reliability was considered excellent. All ICC estimates of intrarater and interrater reliability for the repeated measurements were greater than 0.82, except a study which had pointed out difficult visualization of the posterior thigh.15

Association between MT and muscle CSA or MV

Anatomically, the transverse plane of the anterior thigh (i.e. quadriceps) muscle appears as a semicircle centered at the femur (Figure 1). The equation to calculate the area of a semicircle is π × r2 × 0.5, so it may be that MT2 is useful for predicting muscle CSA. Similarly, a combination of MT2 with limb length may be useful for estimating MV. Correlations between ultrasound-measured MT and the corresponding portion of muscle CSA or MV are presented in Table 2 (anterior thigh MT) and Table 3 (anterior and posterior lower leg MT).13,24–30 The linear relationship between MT and muscle CSA or MV has been observed in the quadriceps,13,24–26 adductor,27 hamstring,31 tibialis anterior,28 and triceps surae13,29 muscles. For example, Abe et al.25 reported a strong correlation (r = 0.91, p < 0.001, n = 52) between ultrasound measured anterior mid-thigh MT and the quadriceps muscle CSA measured by MRI in men. Interestingly, Ogawa et al.27 reported that MT in the upper portion of anterior thigh reflects adductor muscle CSA (r = 0.922, p < 0.001) and MV (r = 0.841, p < 0.001) in young adults (10 men and 10 women). They also reported that when combined with thigh length, anterior upper thigh MT (at 30% of thigh length) became a better predictor for adductor MV (r = 0.949, p < 0.001). Recently, we investigated the relationship between posterior thigh MT and MRI-measured hamstring muscle CSA and MV in women.31 A strong correlation was observed between posterior mid-thigh MT and hamstring muscle CSA at 50% of thigh length (r = 0.848, p = 0.002, n = 10). When using a combination of MT and thigh length (MT × TL) as an independent variable for predicting MV, the correlation coefficient between hamstring MV and posterior mid-thigh MT × TL (r = 0.873, p = 0.001) was higher than the posterior MT alone (r = 0.732, p = 0.016). Whereas the muscle belly of the hamstring is located in the middle to lower portion of the posterior thigh, the muscle belly of the quadriceps muscle is observed in the anterior middle portion of the thigh. The adductor longus and brevis are located in the anterior medial compartment of the thigh, while the adductor magnus is located in the posterior medial compartment, and the peak anatomical muscle CSA of these adductors is observed in the upper portion of the thigh. Based on these anatomical considerations, the ultrasound MT from the anterior upper thigh (30% of thigh length) MT and anterior mid-thigh MT would be the best predictor for evaluating adductor and quadriceps muscle size, respectively. Likewise, hamstring muscle size may also be predicted using posterior thigh MT measured by ultrasound.

Table 2.

Correlations between anterior thigh muscle thickness and quadriceps muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) or quadriceps and adductor muscle volume (MV) measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT)

| Reference | Year | Reference variable | Number of subjects | Subject age range | Reference method | Posture of MT testing | Regressions | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koskelo et al.30 | 1991 | MT | N = 16 (10 boys & 6 girls) | 3–19 yrs | CT | Supine | 0.98 | |

| Sipila et al.24 | 1993 | CSA | W = 34 | 66–85 yrs | CT | Supine | 0.76 | |

| Abe et al.25 | 1997 | CSA | M = 52 | NR | MRI | Standing | Quadriceps CSA (cm2) = 25.2 × aMT50 − 60.7 aMT50, anterior thigh muscle thickness at 50% of thigh length (cm) | 0.91 |

| Miyatani et al.26 | 2002 | MV | M = 46 | 20–70 yrs | MRI | Standing | Quadriceps MV (cm3) = 311.7 × aMT50 +53.3 × LL − 2058 | 0.91 |

| Miyatani et al.13 | 2004 | MV | M = 27 | 23–40 yrs | MRI | Standing | Quadriceps MV (cm3) = 322.9 × aMT50 + 116.4 × LL − 4661 | 0.87 |

| aMT50, anterior thigh muscle thickness at 50% of thigh length (cm); LL, thigh length (cm) | ||||||||

| Ogawa et al.27 | 2012 | MV | N = 20 (10M & 10W) | 28 ± 6 yrs | MRI | Standing | Adductor MV (cm3) = 5.51 × aMT30 × LL − 434.9 | 0.95 |

| aMT30, anterior thigh muscle thickness at 30% of thigh length (cm); LL, thigh length (cm) |

M, men; W, women; NR, not reported; MT, muscle thickness.

Table 3.

Correlations between anterior and posterior lower leg muscle thickness and tibialis anterior muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) or calf muscle volume (MV) measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography (US)

| Reference | Year | Reference variable | Number of subjects | Subject age range | Reference method | Posture of MT testing | Regressions | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martinson and Stokes28 | 1991 | CSA | W = 17 | 18-35 yrs | US | Supine | Tibialis anterior CSA (cm2) = 1.96 × aMT2 + 0.96 | 0.90 |

| aMT, anterior lower leg muscle thickness | ||||||||

| Miyatani et al.13 | 2004 | MV | M = 27 | 23–40 yrs | MRI | Standing | Ankle plantar flexors MV (cm3) = 218.1 × pMT + 30.7 × LL − 1730.4 | 0.91 |

| pMT, posterior lower leg muscle thickness at 30% of lower leg length (cm); LL, lower leg length (cm) | ||||||||

| Bandholm et al.29 | 2007 | MV | CA = 11 | NR | Dissection | Prone | Gastrocnemius MV (cm3) = 85.3 × gMT + 5.0 × LL − 104.9 | 0.70 |

| Soleus MV (cm3) = 73.6 × sMT + 10.6 × LL − 284.4 | 0.81 | |||||||

| gMT, mean of the medial and lateral gastrocnemius | ||||||||

| muscle thickness (centimeter); LL, lower leg length(cm); sMT, soleus muscle thickness (cm) |

M, men; W, women; CA, human cadavers; NR, not reported; MT, muscle thickness.

For the lower leg muscles, Martinson and Stokes28 reported a strong correlation between ultrasound-measured anterior lower leg MT squared (MT2) and tibialis anterior muscle CSA (r = 0.90, p < 0.01, n = 17). Miyatani et al.13 also found a high correlation between anterior lower leg MT and ankle plantar flexors MV (r = 0.806, p < 0.05, n = 14). When combined with lower leg length (LL), the correlation coefficient between ankle plantar flexors MV and anterior lower leg MT × LL (r = 0.910) was higher than the anterior lower leg MT alone. Although there are a limited number of studies, anterior as well as posterior lower leg MT may reflect muscle CSA and MV of the lower leg muscles.

Aside from whole MT of the anterior and posterior aspects of the thigh or lower leg, an isolated MT such as vastus lateralis (VL), gastrocnemius medialis (MG), and soleus (SOL) muscles can also be determined using an ultrasound. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies in vivo concerning the relationship between ultrasound-measured isolated MT and MRI- or CT-measured muscle CSA and MV. However, a dissection study29 reported that gastrocnemius MV (r = 0.70, p = 0.016) as well as soleus MV (r = 0.81, p = 0.003) was correlated with a combination of those isolated MT and lower leg length (Table 3).

Association between MT and muscle function

It is well known that anatomical muscle CSA and MV are valuable predictors of muscular strength and power output.1,8,9 As described above, ultrasound-measured MT is closely related to anatomical muscle CSA and MV. Thus, there is expected to be a good relationship between MT and muscular function. Correlations between anterior thigh MT and knee extension strength are presented in Table 4. There are moderate to high correlation coefficients (ranged between 0.41 and 0.70) between anterior mid-thigh MT and isometric knee extension strength in young and older adults.32–37 For example, Watanabe et al.36 investigated the interrelationship between anterior thigh MT, echo intensity, and maximum isometric knee extension torque in older men (n = 184, 65–91 years). They found that thigh MT was positively correlated to knee extension strength (r = 0.411, p < 0.01), while echo intensity was negatively correlated to the strength (r = −0.333, p < 0.01). Freilich et al.32 measured anterior mid-thigh MT using an ultrasound in 58 men and 82 women aged 18–50 years. The authors reported a significant positive correlation between MT and isometric knee extension strength in men (r = 0.55, p < 0.001) and women (r = 0.56, p < 0.001). Furthermore, Abe et al.37 recently examined the relationships between anterior and posterior thigh MT and isometric knee extension and flexion strength in older men (n = 33) and found that there was a relatively strong correlation between anterior thigh MT and knee extension strength (r = 0.703, p < 0.001). Compared to those ultrasound studies, Maughan et al.8 investigated the association between MRI-measured quadriceps muscle CSA and knee extension strength in young men (n = 25) and women (n = 25). They found that there was moderate correlation between quadriceps CSA and knee extension strength in men (r = 0.59, p < 0.01) and women (r = 0.51, p < 0.01). Overend et al.38 observed a strong correlation between computer tomography (CT)-measured quadriceps muscle CSA and knee extension strength in young men (r = 0.829, p < 0.001, n = 13), but the correlation was slightly lower in older men (r = 0.667, p = 0.025, n = 12). Similarly, Akima et al.39 also reported a strong correlation coefficient between MRI-measured quadriceps CSA and knee extension strength in men (r = 0.827, p < 0.001, n = 90), but not in women (r = 0.657, p < 0.001, n = 79). Based on previous studies, therefore, the results suggest that ultrasound-measured anterior thigh MT is a variable predictor for evaluating maximum knee extension strength, which is similar to results of MRI/CT measured muscle CSA.

Table 4.

Correlations between anterior thigh muscle thickness and knee extension strength in children and adults

| Reference | Year | Number of subjects | Subject age range | Type of exercise | Mode of contraction | Posture of MT testing | Tested muscle | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freilich et al.32 | 1995 | M = 58 | 18–50 yrs | Knee extension | Isometric | Seated upright | Quadriceps | 0.55 |

| W = 80 | 0.56 | |||||||

| Moreau et al.33 | 2010 | N = 12 | 7–20 yrs | Knee extension | Isometric | Supine | Rectus femoris | 0.77 |

| (10 girls & 2 boys) | Vastus lateralis | 0.88 | ||||||

| Cadore et al.34 | 2012 | M = 31 | 65 ± 5 yrs | Knee extension | Isometric | Supine | Quadriceps | 0.43 |

| Vastus intermedius | 0.42 | |||||||

| Vastus medialis | 0.42 | |||||||

| Isokinetic | Quadriceps | 0.63 | ||||||

| Vastus intermedius | 0.53 | |||||||

| Vastus medialis | 0.55 | |||||||

| Fukumoto et al.35 | 2012 | W = 92 | 51–87 yrs | Knee extension | Isometric | Supine | Quadriceps | 0.47 |

| Watanabe et al.36 | 2013 | M = 184 | 65–91 yrs | Knee extension | Isometric | Standing | Quadriceps | 0.41 |

| Strasser et al.40 | 2013 | YP = 26 | 18–35 yrs | Knee extension | Isometric | Supine | Rectus femoris | 0.88 |

| Intermedius | 0.92 | |||||||

| Vastus lateralis | 0.84 | |||||||

| Vastus medialis | 0.92 | |||||||

| OP = 26 | 60–80 yrs | Rectus femoris | 0.83 | |||||

| Intermedius | 0.82 | |||||||

| Vastus lateralis | 0.76 | |||||||

| Vastus medialis | 0.88 | |||||||

| Abe et al.37 | 2014 | M = 33 | 52–82 yrs | Knee extension | Isometric | Standing | Quadriceps | 0.70 |

M, men; W, women; YP, young patients; OP, old patients; MT, muscle thickness.

Three recent studies33,34,40 measured isolated MT of the quadriceps such as rectus femoris MT, vastus lateralis MT, vastus medialis MT, and vastus intermedius MT. For instance, Strasser et al.40 reported a strong correlation coefficient between isolated MT of the quadriceps and isometric knee extension strength in both young (r = 0.838–0.92, p < 0.001, n = 26) and old (r = 0.756–0.875, p < 0.001, n = 26) patients. On the other hand, Cadore et al.34 reported a moderate correlation coefficient between isolated quadriceps MT and knee extension strength in older men (r = 0.42, p < 0.05, n = 31). The results suggest that the correlation coefficients between isolated quadriceps MT and knee extension strength are almost identical to the results of anterior thigh MT (i.e. quadriceps MT) and MRI/CT measured muscle CSA.

Whereas MT is a single dimensional variable, ultrasound can also measure multidimensional variables such as muscle CSA and MV. Barber et al.41 investigated the validity and reliability of in vivo MV of the medial gastrocnemius using a freehand three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound. They reported that the freehand 3D ultrasound overestimated MV by approximately 5 mL (mean difference, 2.1 ± 4.0%) at an ankle angle of dorsiflexion and underestimated MV by approximately 2 mL (mean difference, 0.4 ± 3.9%) at an ankle angle of planterflexion compared to MRI-measured MV. The ICC for repeated 3D measures of MV was 0.99 in the three ankle positions. Over the last decade, however, a limited number of studies41,42 have evaluated MV in the limb using the 3D ultrasound technique, which may be due to it being a cumbersome procedure.

To our astonishment, there are a few studies that have been completed regarding the functional relationships with ultrasound measured MT in the lower extremity (Table 5), except with anterior thigh MT (Table 4). If MT measured by ultrasound is closely associated with muscle CSA and MV of each muscle, measured MT should be related to muscular function. However, the muscle belly of each muscle is located in a different anatomical position among individuals. It is clear that future studies are required to investigate these findings further.

Table 5.

Correlations between lower leg muscle thickness and ankle joint strength or gait performance

| Reference | Year | Number of subjects | Subject age range | Type of exercise | Mode of contraction | Posture of MT testing | Tested muscle | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moreau et al.33 | 2010 | CP = 20 | 8–20 yrs | Ankle dorsiflexion | Isometric | Sitting | Tibialis anterior | 0.57 |

| (10M & 10W) | Walking | Fast | 0.67 |

M, men; W, women; CP, cerebral palsy; MT, muscle thickness.

Conclusion

Anterior upper-thigh MT and anterior mid-thigh MT, respectively, would be the best predictor for evaluating adductor and quadriceps muscle CSA or MV, while posterior thigh MT may be a predictor for evaluating hamstring muscle size. Similar results are observed in the lower leg in that anterior as well as posterior lower leg MT may reflect muscle CSA and MV of the lower leg muscles, although there are a limited number of studies. Anterior thigh MT is a variable predictor for evaluating knee joint strength. Unfortunately, few studies exist regarding the functional relationships with ultrasound MT in the lower extremity, except in anterior thigh MT. Future studies are needed to clarify these findings further.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: This work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Guarantor: TA.

Contributorship: All authors (TA, JPL, and RST) searched the previous studies. TA summarized the data describing the previous studies and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final draft.

References

- 1.Ikai M, Fukunaga T. Calculation of muscle strength per unit cross-sectional area of human muscle by means of ultrasonic measurement. Int Z Angew Physiol 1968; 26: 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukunaga T, Miyatani M, Tachi M, et al. Muscle volume is a major determinant of joint torque in humans. Acta Physiol Scand 2001; 172: 249–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanada K, Kearns CF, Kojima K, et al. Peak oxygen uptake during running and arm cranking normalized to total and regional skeletal muscle mass measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Appl Physiol 2005; 93: 687–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narici MV, Roi GS, Landoni L. Force of knee extensor and flexor muscles and cross-sectional area determined by nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1988; 57: 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aagaard P, Andersen JL, Dyhre-Poulsen P, et al. A mechanism for increased contractile strength of human pinnate muscle in response to strength training: changes in muscle architecture. J Physiol 2001; 534: 613–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abe T, Kearns CF, Sato Y. Muscle size and strength are increased following walk training with restricted venous blood flow from the leg muscle, Kaatsu-walk training. J Appl Physiol 2006; 100: 1460–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harber MP, Konopka AR, Douglass MD, et al. Aerobic exercise training improves whole muscle and single myofiber size and function in older women. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009; 297: R1452–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maughan RJ, Watson JS, Weir J. Strength and cross-sectional area of human skeletal muscle. J Physiol 1983; 338: 37–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shephard RJ, Bouhlel E, Vendewalle H, et al. Muscle mass as a factor limiting physical work. J Appl Physiol 1988; 64: 1472−9–1472−9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abe T, Loenneke JP, Thiebaud RS, Loftin M. Morphological and functional relationships with ultrasound measured muscle thickness of the upper extremity and trunk. Ultrasound 2014; 22: 229−35–229−35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukunaga T, Matsuo A, Ishida Y, et al. Study for measurement of muscle and subcutaneous fat thickness by means of ultrasonic B-mode method. Jpn J Med Ultrasonics 1989; 16: 170–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawakami Y, Abe T, Fukunaga T. Muscle-fiber pennation angles are greater in hypertrophied than in normal muscles. J Appl Physiol 1993; 74: 2740–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyatani M, Kanehisa H, Ito M, et al. The accuracy of volume estimates using ultrasound muscle thickness measurements in different muscle groups. Eur J Appl Physiol 2004; 91: 264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raj IS, Bird SR, Shild AJ. Reliability of ultrasonographic measurement of the architecture of the vastus lateralis and gastrocnemius medialis muscles in older adults. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2012; 32: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thoirs K, English C. Ultrasound measures of muscle thickness: intra-examiner reliability and influence of body position. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2009; 29: 440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tillquist M, Kutsogiannis DJ, Wischmeyer PE, et al. Bedside ultrasound is a practical and reliable measurement tool for assessing quadriceps muscle layer thickness. J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2014; 38: 886–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abe T, Loenneke JP, Thiebaud RS, et al. Age-related site-specific muscle wasting of upper and lower extremities and trunk in Japanese men and women. Age (Durdr) 2014; 36: 813–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss LW, Clark FC. Ultrasonic protocols for separately measuring subcutaneous fat and skeletal muscle thickness in the calf area. Phys Ther 1985; 65: 477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legerlotz K, Smith HK, Hing WA. Variation and reliability of ultrasonographic quantification of the architecture of the medial gastrocnemius muscle in young children. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2010; 30: 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crofts G, Angin S, Mickle KJ, et al. Reliability of ultrasound for measurement of selected foot structures. Gait Posture 2014; 39: 35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konig N, Cassel M, Intziegianni K, et al. Inter-rater reliability and measurement error of sonographic muscle architecture assessment. J Ultrasound Med 2014; 33: 769–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abe T, Thiebaud RS, Loenneke JP, et al. Association between forearm muscle thickness and age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass, handgrip and knee extension strength and walking performance in old men and women: a pilot study. Ultrasound Med Biol 2014; 40: 2069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res 2005; 19: 231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sipila S, Suominen H. Muscle ultrasonography and computed tomography in elderly trained and untrained women. Muscle Nerve 1993; 16: 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abe T, Kawakami Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Effects of 20 days bed rest on muscle morphology. J Gravit Physiol 1997; 4: S10–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyatani M, Kanehisa H, Kuno S, et al. Validity of ultrasonograph muscle thickness measurements for estimating muscle volume of knee extensors in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 2002; 86: 203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogawa M, Mitsukawa N, Bemben MG, et al. Ultrasound assessment of adductor muscle size using muscle thickness of the thigh. J Sport Rehabil 2012; 21: 244–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinson H, Stokes MJ. Measurement of anterior tibial muscle size using real-time ultrasound imaging. Eur J Appl Physiol 1991; 63: 250–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandholm T, Sonne-Holm S, Thomsen C, et al. Calf muscle volume estimations: implications for botulinum toxin treatment? Pediatr Neurol 2007; 37: 263–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koskelo EK, Kivisaari LM, Saarinen UM, et al. Quantitation of muscles and fat by ultrasonography: a useful method in the assessment of malnutrition in children. Acta Pediatr Scand 1991; 80: 682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abe T, Loenneke JP, Thiebaud RS. Ultrasound assessment of hamstring muscle size using posterior thigh muscle thickness. Clin Physiol Func Imaging 2014 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freilich RJ, Kirsner RL, Byrne E. Isometric strength and thickness relationships in human quadriceps muscle. Neuromusc Disord 1995; 5: 415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreau NG, Simpson KN, Teefey SA, et al. Muscle architecture predicts maximum strength and is related to activity levels in cerebral palsy. Phys Ther 2010; 90: 1619–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cadore EL, Izquierdo M, Conceicao M, et al. Echo intensity is associated with muscle power and cardiovascular performance in elderly men. Exp Gerontol 2012; 47: 473–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukumoto Y, Ikezoe T, Yamada Y, et al. Skeletal muscle quality assessed from echo intensity is associated with muscle strength of middle-aged and elderly persons. Eur J Appl Physiol 2012; 112: 1519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe Y, Yamada Y, Fukumoto Y, et al. Echo intensity obtained from ultrasonography images reflecting muscle strength in elderly men. Clin Interv Aging 2013; 8: 993–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abe T, Kojima K, Stager JM. Skeletal muscle mass and muscular function in master swimmers is related to training distance. Rejuvenation Res 2014; 17: 415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Overend TJ, Cunningham DA, Kramer JF, et al. Knee extensor and knee flexor strength: cross-sectional area ratios in young and elderly men. J Gerontol 1992; 47: M204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akima H, Kano Y, Enomoto Y, et al. Muscle function in 164 men and women aged 20-84 yr. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001; 33: 220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strasser EM, Draskovits T, Praschak M, et al. Association between ultrasound measurements of muscle thickness, pennation angle, echogenicity and skeletal muscle strength in the elderly. Age (Durdr) 2013; 35: 2377–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barber L, Barrett R, Lichtwark G. Validation of a freehand 3D ultrasound system for morphological measures of the medial gastrocnemius muscle. J Biomech 2009; 42: 1313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacGillivray TJ, Ross E, Simpson HA, et al. 3D freehand ultrasound for in vivo determination of human skeletal muscle volume. Ultrasound Med Biol 2009; 35: 928–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]