Abstract

The ductus arteriosus holds major functional importance within the fetal circulation, and anomalies within the ductus arteriosus may interfere with the integrity of the fetal circulation. Ductus arteriosus aneurysm, previously considered a rare lesion, is now a well-reported finding in infancy with some reports describing this finding in the prenatal period. Postnatally, most ductus arteriosus aneurysms resolve spontaneously; however, a small group of infants show complications such as connective-tissue disorders, thrombo-embolism, compression of surrounding thoracic structures and life-threatening spontaneous rupture requiring surgical correction. As such, postnatal assessment in this group is recommended.

Keywords: Ductus arteriosus aneurysm, ductus arteriosus, prenatal, echocardiography

Case history

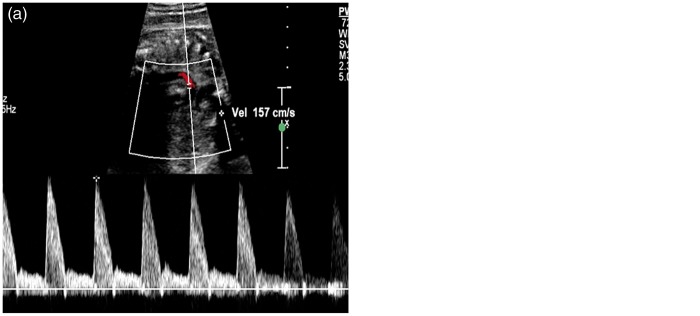

A 32-year-old G1P0 woman was referred to us at 34 weeks’ gestation for a growth assessment. She had previously had a low-risk first trimester combined screen for aneuploidy, followed by an unremarkable 20 weeks’ morphology scan. Apart from well-controlled maternal hypothyroidism by thyroxin supplements, her antenatal course had been progressing well without any complication. On ultrasound examination at 34 weeks, a routine review of the heart showed normal four-chamber and outflow tracts views. The three-vessel view subjectively demonstrated an abnormal saccular, fusiform distension in the region of the proximal descending aorta at the area of the ductus insertion (Figures 1 and 2). The maximal dimension at this dilatation measured 10 mm. (Normal ductus arteriosus ≤7 mm at term).1 This aneurysmal dilatation of the ductus arteriosus was also identified on sagittal views of the ductal arch. Colour flow Doppler showed a turbulent, ‘swirling’ appearance to flow within the aneurysm with normal antegrade flow into the descending aorta. Normal flow in the ductus arteriosus is unidirectional and antegrade (Figure 3). A detailed fetal echocardiography was performed, confirming no other structural anomaly or resultant haemodynamic alteration due to this aneurysm. The pregnancy continued on an uneventful course, and a repeat assessment of the ductus arteriosus aneurysm (DAA) was done at 36 weeks by another fetal echocardiogram. Mild increase in size of the DAA (11.5 mm) with no other structural anomaly was again noted. Spontaneous, uncomplicated vaginal birth ensued at 38 weeks with no special nursing care requirement and airway, feeding or perfusion concerns. Initial postnatal echocardiogram on the first day of life showed the aneurysm with no obstruction to the aortic arch and no cardiac compromise. Another follow-up echocardiogram in the third postnatal week showed complete resolution of the DAA.

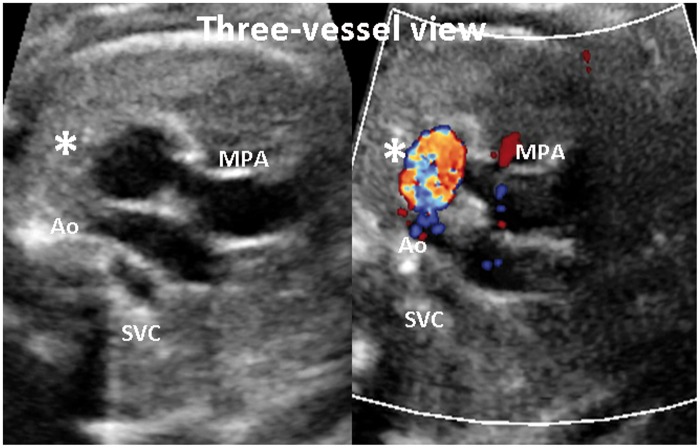

Figure 1.

Three-vessel view in diagnosis

Ao: aorta; SVC: superior vena cava; MPA: main pulmonary artery; *: Ductus arteriosus aneurysm

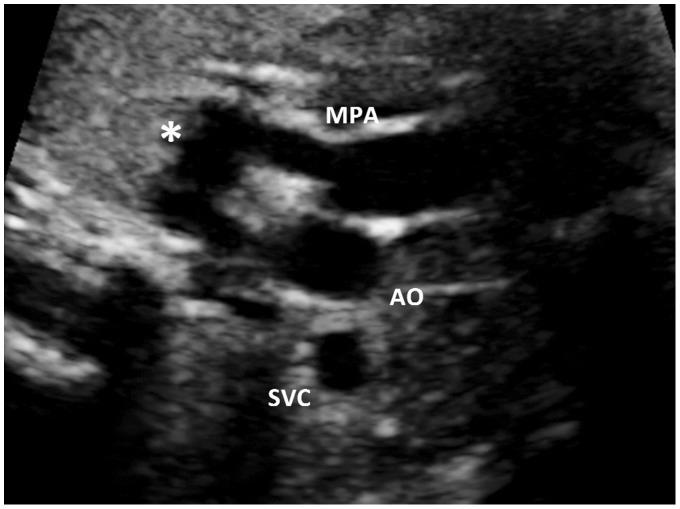

Figure 2.

Three-vessel view including the ductus arteriosus

*: Dilated ductus arteriosus; MPA: main pulmonary artery; AO: aorta; SVC: superior vena cava

Figure 3.

(a) Pulsed Doppler analysis of normal ductus arteriosus and (b) at the aneurysm showing bidirectional flow

Discussion

DAA is an increasingly recognised lesion in the prenatal period. Although the outlook is generally benign, there is a small possibility of significant complications from this lesion. Most DAAs appear to be isolated cardiac defects. The earliest large series published in 2000 evaluated 200 consecutive third trimester pregnancy ultrasounds with a DAA detection rate of 1.5%.2 Of these, most babies were noted to be asymptomatic after birth and thought to have perhaps been unlikely to be detected without a prenatal echocardiogram. Another prospective study evaluating 548 neonates concluded a much higher incidence of 8.8% suggesting that this finding may even be a normal anatomical variant of the late third trimester.3–5 There is a reported association with larger-than-average birth weights and with diabetic pregnancies. Fetal echocardiographic evaluations in the above pregnancies have demonstrated a hyperdynamic right heart function and altered umbilical artery resistance patterns. This may indicate presence of altered circulatory factors with a potential to alter the feto-placental unit and cause dilatation of the ductus arteriosus.6

The pathogenesis of this condition remains ill defined, although the following theories have been postulated7: (a) Congenital weakness in the media of the ductus arteriosus from a natural late process of degeneration and necrosis in the third trimester; (b) physiological flow increases through the ductus closer to term; (c) possible intrauterine constriction of the ductus close to the pulmonary end with poststenotic dilation and (d) defective elastin resulting in abnormal intimal cushion formation.

The three-vessel view has long been acclaimed as a useful view in the diagnosis of fetal cardiac anomalies.8 Sweeping cranially to the standard axial four-chamber view and going from right to left shows the cross-sectional superior vena cava and the transverse aortic root, and the pulmonary artery extending into the ductus. This image is currently standard in our institutional second trimester cardiac screening protocol. As low-risk morphology scans are not always performed within the institution, we also routinely attempt to review anatomy when patients present for a third trimester scan for any indication. Particularly the heart is imaged, attempting as many views as feasible to establish anatomy. In this case, the three-vessel view proved the first pointer to the cardiac abnormality in an otherwise routine growth evaluation. Two-dimensional evaluation clearly revealed the dilated, tortuous ductus arteriosus connecting the pulmonary artery and the aorta before measurements and colour Doppler confirmed the diagnosis. Jackson et al.9 previously described a similar observation when they presented four cases of fetal DAA identified through the three-vessel view.

All previously published reports on prenatal DAA indicate that ongoing surveillance and counselling has been through paediatric cardiology. Most of them also suggest progressive decrease in size postnatally with larger case series reporting spontaneous resolution in over 70% of infants by about the fifth week after birth.3–5,10 Dyamenahalli et al.2 also described formation of thrombi in some cases in their series between the third and tenth day of life, although both the DAA and the newly formed thrombi showed complete resolution by about one month after birth.

Although rare, the literature review also highlighted serious complications in selected cases. There exist reports of poor outcomes following spontaneous rupture of DAA.11,12 Particularly, infants with a proven associated connective-tissue disorder such as Marfan’s syndrome13 or Ehlers–Danos syndrome appear to demonstrate the highest risk of spontaneous rupture.14

Although most cases of small DAA appear to run a short-lived, benign course, surgical correction has shown a role in managing some patients. Infants who showed a rapid increase in the size of the aneurysm (with or without thrombus formation), or local extension of the aneurysm into the surrounding thoracic structures, resulting in bronchial airway obstruction and nerve palsies, particularly the recurrent laryngeal nerve, were shown to be likely surgical candidates for correction.15 Equally critically, some reports described DAA with vascular extension involving compression of the pulmonary arteries and aorta also as prime candidates for surgical intervention.16

Once antenatal diagnosis has been made, the most common practice guideline emerging from review of other reported cases is for postnatal cardiology follow-up, although an acceptable wait period for resolution or timing of intervention is still not well defined. Many earlier isolated reports appeared to recommend prompt surgical intervention after birth; however, the more recent larger series in this area suggest that persistence of this finding beyond four to six weeks, or rapid increase in size, or significant airway, vascular and neurological complications as more appropriate indications to plan surgical correction, given that most observed cases of congenital DAA showed spontaneous resolution.

We report this case to show the importance of at least a cursory cardiac review even in late pregnancy growth scan to identify late onset cardiac anomalies as well as to show the usefulness of the three-vessel view in the diagnosis of prenatal congenital DAA. Significant potential complications mean that congenital DAA when recognised should be referred to the paediatric cardiologist for postnatal assessment and possible treatment, if warranted.

Declarations

Competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding: This work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval: Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details and images from this case.

Guarantor: SG.

Contributorship: SG made the diagnosis and discussed it with AJS. DH confirmed the diagnosis and provided paediatric follow-up. SG wrote the manuscript and discussed with AJS and DH. All authors approved the final version. Revisions were subsequently made to address queries and include suggestions made by the editors.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Departments of Neonatology at the Royal Women’s Hospital and Paediatric Echo at the Royal Children’s Hospital for performing the postnatal echocardiograms.

References

- 1.Pasquini L, Mellander M, Seale A, et al. Z-scores of the fetal aortic isthmus and duct: an aid to assessing arch hypoplasia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007; 29: 623–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyamenahalli U, Smallhorn JF, Geva T, et al. Isolated ductus arteriosus aneurysm in the fetus and infant: a multi-institutional experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36: 262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornberger LK. Congenital ductus arteriosus aneurysm. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 348–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jan SL, Hwang B, Fu YC, et al. Isolated neonatal ductus arteriosus aneurysm. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 342–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tseng JJ, Jan SL. Fetal echocardiographic diagnosis of isolated ductus arteriosus aneurysm: a longitudinal study from 32 weeks of gestation to term. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005; 26: 50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghandi JA, Zhang XY, Maidman JE. Fetal cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac function in diabetic pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995; 173: 1132–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lund JT, Hansen D, Brocks V, et al. Aneurysm of the ductus arteriosus in the neonate. Three case reports with a review of the literature. Pediatr Cardiol 1992; 13: 222–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yagel S, Arbel R, Anteby EY, et al. The three vessels and trachea view (3VT) in fetal cardiac scanning. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002; 20: 340–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson CM, Sandor GGS, Lim K, et al. Diagnosis of fetal ductus arteriosus aneurysm: importance of the three-vessel view. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005; 26: 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puder KS, Sherer DM, Ross RD, et al. Prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis of ductus arteriosus aneurysm with spontaneous neonatal closure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1995; 5: 342–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferlic RM, Hofschire PJ, Mooring PK. Ruptured ductus arteriosus aneurysm in an infant: report of a survivor. Ann Thorac Surg 1975; 20: 456–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ithuralde M, Halloran KH, Fishbone G, et al. Dissecting aneurysm of the ductus arteriosus in the newborn infant. Am J Dis Child 1971; 122: 165–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crisfield RJ. Spontaneous aneurysm of the ductus arteriosus in a patient with Marfan’s syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1971; 62: 243–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang JP, Chang CH, Sheih MJ. Aneurysmal dilation of patent ductus arteriosus in a case of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg 1987; 44: 656–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hornung TS, Nicholson IA, Nunn GR, et al. Neonatal ductus arteriosus aneurysm causing nerve palsies and airway compression: surgical treatment by decompression without excision. Pediatr Cardiol 1999; 20: 158–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fripp RR, Whitman V, Waldhausen JA, et al. Ductus arteriosus aneurysm presenting as pulmonary artery obstruction; diagnosis and management. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985; 6: 234–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]