Abstract

Aim

To compare contrast-enhanced ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography in the evaluation of complex renal cysts using the Bosniak classification.

Methods

Forty-six patients with 51 complex renal cysts were prospectively examined using contrast-enhanced ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography and images analysed by two observers using the Bosniak classification. Adverse effects and patients’ preference were assessed for both modalities.

Results

There was complete agreement in Bosniak classification between both modalities and both observers in six cysts (11.8%). There was agreement of Bosniak classification on both modalities in 21 of 51 cysts (41.2%) for observer 1 and in 17 of 51 cysts (33.3%) for observer 2. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound gave a higher Bosniak classification than corresponding contrast-enhanced computed tomography in 31 % of cysts by both observers. Histological correlation was available in three lesions, all of which were malignant and classified as such simultaneously on both modalities by at least one observer, with remaining patients followed up with US or CT for 6–24 months. No adverse or side effects were reported following the use of US contrast, whilst 63.6% of patients suffered minor side effects following the use of CT contrast. 81.8% of the surveyed patients preferred contrast-enhanced ultrasound to contrast-enhanced computed tomography.

Conclusion

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound is a feasible tool in the evaluation of complex renal cysts in a non-specialist setting. Increased contrast-enhanced ultrasound sensitivity to enhancement compared to contrast-enhanced computed tomography, resulting in upgrading the Bosniak classification on contrast-enhanced ultrasound, has played a role in at best moderate agreement recorded by the observers with limited experience, but this would be overcome as the experience grows. To this end, we propose a standardised proforma for the contrast-enhanced ultrasound report. The benefits of contrast-enhanced ultrasound over contrast-enhanced computed tomography include patients’ preference and avoidance of ionising radiation or nephrotoxicity, as well as lower cost.

Keywords: Complex renal cyst, Bosniak classification, contrast-enhanced ultrasound, contrast enhanced computed tomography, renal cell carcinoma

Introduction

Renal cysts can be found in 50% of the population over 50 years of age on autopsy1 and are commonly encountered as incidental findings in most diagnostic imaging investigations.2,3 Simple cysts have no malignant potential and need no follow-up.4 About 5–10% of all renal cysts, however, are complex, and 5–10% of those prove to be tumours.5 Renal is the third most common genito-urinary malignancy after prostate and bladder.6 Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) represents 2% of all cancer diagnoses in humans.7,8 The mainstay of RCC treatment is surgical removal of the tumour. Approximately 15% of RCCs are cystic, resulting either from extensive necrosis of an underlying solid tumour or representing a primary cystic renal carcinoma.9 The Bosniak classification of renal cysts, first introduced in 198610 and modified in 1997,11 grades renal cysts into categories I to IV. The prevalence of malignancy in each of the Bosniak categories has been reported in a metaanalysis as: category I – 0%: category II – 15.6%, category III – 65.3%; and category IV – 91.7%.12 The newer category IIF cysts were all benign in the same metaanalysis but fewer studies reported on them. Bosniak category III and IV cysts require surgical intervention (accepting that some of the category III lesions will have benign histology); Bosniak category I and II cysts require no treatment13 and Bosniak category IIF cysts require follow-up over a period of time. The malignant potential of complex renal cysts is based on their architecture and enhancement. Enhancement, defined as demonstration of contrast agent within an area of a complex renal cyst, is equivalent to demonstration of the existence of blood flow within this area (perfused tissue).14 Increased enhancement raises the likelihood of malignancy.15

Computed tomography (CT) with iodinated intravenous (IV) contrast (CECT) has been a gold standard to detect enhancement in a complex renal cyst. Even though unenhanced ultrasound (US) is the first choice investigation in renal imaging due to lack of radiation or nephrotoxic effects,14 incidentally found complex renal cysts subsequently require CECT for Bosniak classification.7

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) has been demonstrated by several studies to have a sensitivity and specificity similar to or better than CECT and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (MR) imaging in the differentiation of benign and malignant cystic renal lesions.16–19 CEUS detects even minimal flow within cyst walls, septations or nodules,20 allowing the application of the Bosniak classification. To our knowledge, the performance of CEUS for this purpose in a routine National Health Service practice has not yet been evaluated.

Objective

The main purpose of this study was to compare CEUS and CECT in the evaluation of renal cysts using the Bosniak classification (Table 1). We also compared the prevalence of adverse reactions for CECT and CEUS contrast agents and patients’ acceptability of CECT and CEUS procedures.

Table 1.

Modified Bosniak classification

| The Bosniak renal cyst classification system | |

|---|---|

| Category | Criteria and management |

| I | A benign simple cyst with hairline-thin wall that does not contain septa, calcifications or solid components; it has water attenuation and does not enhance; no intervention is needed |

| II | A benign cystic lesion that may contain a few hairline-thin septa in which perceived (not measurable) enhancement may be appreciated; fine calcification or a short segment of thickened calcification may be present in the wall or septa; uniformly high-attenuating lesions (<3 cm) that are sharply marginated and do not enhance are included in this group; no intervention is neededa |

| IIFb | Cysts may contain multiple hairline-thin septa; perceived (not measurable) enhancement of a hairline-thin septum or wall can be identified; there may be minimal thickening of wall or septa, which may contain calcification that may be thick and nodular, but no measurable contrast enhancement is present; there are no enhancing soft-tissue components; totally intrarenal nonenhancing high-attenuating renal lesions (>3 cm) are also included in this category; these lesions are generally well marginated; they are thought to be benign but need follow-up to prove their benignity by showing stabilitya |

| III | Cystic masses with thickened irregular or smooth walls or septa and in which measurable enhancement is present; these masses need surgical intervention in most cases, as neoplasm cannot be excluded; this category includes complicated hemorrhagic or infected cysts, multilocular cystic nephroma, and cystic neoplasms; these lesions need histological diagnosis, as even gross observation by the urologist at surgery or the pathologist at gross pathologic evaluation is frequently indeterminate |

| IV | Clearly malignant cystic masses that can have all of the criteria of category III but also contain distinct enhancing soft tissue components independent of the wall or septa; these masses are clearly malignant and need to be removed |

Perceived enhancement refers to enhancement of hairline-thin or minimally thickened walls or septa that can be visually appreciated when comparing unenhanced and contrast-enhanced CT images side-by-side and on subtracted MR images datasets. This “enhancement” occurs in hairline-thin or smooth minimally thickened septa/walls and, therefore, cannot be measured or quantified. The authors believe tiny capillaries supply blood (and contrast material) to these septa/walls, which are appreciated because of higher doses of intravenous contrast material and thinner CT and MR imaging sections.

“F” indicates follow-up needed.

Source: Israel and Bosniak.28

Materials and methods

Patients

Ethical approval was granted by the local Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients who were pregnant, had renal failure (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of ≤60 ml/min), allergy to either CECT or CEUS contrast agent, patients with history of unstable angina, myocardial infarction within last six weeks, severe pulmonary hypertension or right-to-left cardiac shunts were excluded. Between July 2009 and July 2011, 46 patients with a total of 51 complex cysts detected by non-enhanced US either incidentally or during work up of urinary tract symptoms (including haematuria) were enrolled and underwent CECT and CEUS examinations within two weeks of each other in a random order. CECT has been a standard modality used in our department to investigate complex renal cysts prior to the study. CEUS has been used for several years in the characterisation of incidental liver lesions, but only a few CEUS examinations of renal lesions had been performed in the department prior to the study.

CECT

CECT scans were performed according to existing departmental protocol. The first 13 patients were scanned using a Toshiba Asteion 4-slice multi-detector CT scanner (Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Zoetermeer, Holland). The remaining 33 patients were scanned on a Toshiba Premium Aquillion 160-slice multi-detector CT scanner. Unenhanced CT images were obtained first, followed by injection of 95–100 ml of Omnipaque 300 (GE Healthcare, Hatfield, UK) at the rate of 2.5–3.5 ml/s and contrast-enhanced imaging at 70 s (corticomedullary phase) and 3 min (nephrographic phase), using 3 mm slice thickness.

CEUS

All US scans were performed by the same sonographer with eight years’ experience, using a Toshiba Medical Systems Aplio XG. A 5.0 MHz curvilinear abdominal transducer was used for all scans using differential tissue harmonics. Contrast-enhanced images were acquired using dedicated low-mechanical index Radiology Contrast Harmonic Imaging Kit Model USHR-790A. SonoVue™ (Bracco, Milan, Italy) was used as the sonographic contrast agent in all cases, with a single bolus injection of 2.4 ml followed by a flush of 10 ml bolus injection of sodium chloride solution (0.9%). Continuous digital cine-clips representing the dynamic contrast enhancement within the cyst were stored continuously during the corticomedullary phase (0–60 s post-injection), nephrographic phase (60–120 s post-injection) and late phase (120–180 s post-injection). The sonographer had no access to the CECT images.

Image interpretation

Two radiologists with nine and six years’ experience each independently analysed anonymised CECT and CEUS images of every cyst, blinded to the result of the alternative modality. Using a separate customised proforma for CECT and CEUS, number and thickness of septa, presence of any soft tissue nodule, calcification (type and amount) and any contrast-enhancement within the cyst, its wall or soft tissue nodules were documented for both modalities.

CECT images were analysed on e-Film Workstation 2.1 (Version 2002) (Merge Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA). Areas of perceived enhancement were interrogated, their Hounsfield unit (HU) measurements obtained on the pre-contrast and post-contrast images and quantitative measurement of enhancement calculated and recorded.

CEUS analysis was carried out by reviewing images stored on the US machine. Areas of perceived enhancement on CEUS scans were subjectively graded as 1+, 2+ or 3+ (in the absence of a reliable quantitative system), and the time of beginning and end of enhancement recorded.

A modified Bosniak classification was then assigned by each radiologist to each cyst on each imaging modality. The proforma used for the CEUS report is available with the online version of this article at http://ult.sagepub.com. It additionally recorded the pattern of vascularity described by Quaia et al.16 as an aid in assigning a Bosniak classification to a cyst on CEUS.

Statistical analysis

Cohen’s kappa statistic (κ) was used to determine agreement between CEUS and CECT in Bosniak grading. Agreement was considered poor if the κ value was less than 0.20, fair between 0.21 and 0.40, moderate between 0.41 and 0.60, good between 0.61 and 0.80 and very good between 0.81 and 1.00.21

McNemar statistics were used to calculate the sample size required, with alpha or type I error set to 0.05, odds ratio 0.25, power of 0.8, a total sample requirement of 46 cysts. All statistical analyses were carried out using STATA/IC software version 12.0 (STATA Corporation, TX, USA)

Patient’s perspective questionnaires

After the second of the two scans, patients were given a questionnaire (available with the online version of this article at http://ult.sagepub.com) to assess their experience of both scans. The questionnaires were collated by the sonographer performing CEUS, who also had access to the CECT contrast documentation records.

Results

Baseline demographic and clinical data

Fifty-one complex renal cysts were imaged in 46 patients (27 male and 19 female) with a mean age of 61.2 years (36–94 years). The maximum diameter of the cysts ranged from 11 mm to 107 mm (mean 34 mm).

Bosniak classification

The full data set showing the agreement between modalities and observers in assigning Bosniak classifications is available with the online version of this article at http://ult.sagepub.com. Typical examples of CEUS enhancement pattern in different Bosniak grades are shown in Figures 1–5.

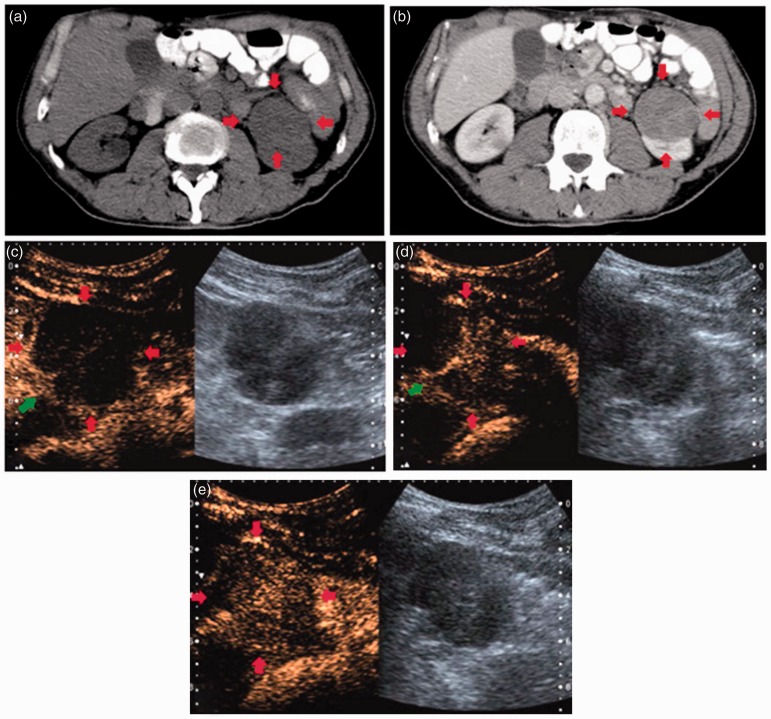

Figure 2.

CT scan of a cyst indicated by red arrows: unenhanced axial scan (a) and enhanced axial scan (b). CEUS scan of the same cyst (images (c) and (d)). Septation indicated by green arrows. Postcontrast enhancement of intracystic septa on CEUS is difficult to appreciate on CECT. The cyst was classified as Bosniak II on CECT and Bosniak IIF on CEUS.

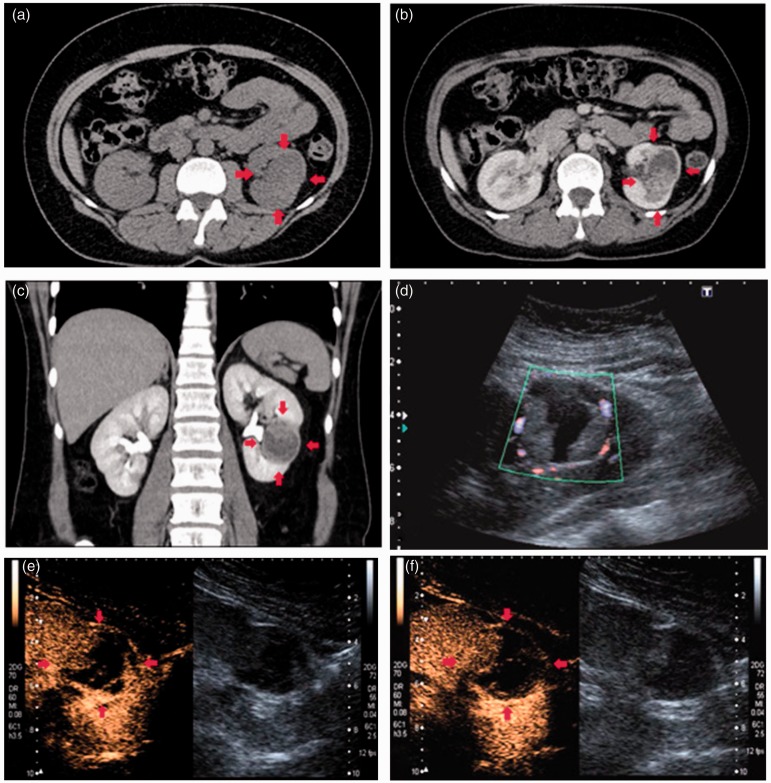

Figure 3.

Unenhanced axial CT scan of a cyst (a). Enhanced axial scan of cyst (b) showing some enhancement within cyst. CEUS images show a feeding vessel in the left lower quadrant of cyst (green arrow) in image (c) with gradual filling of the cyst with contrast ((d) and (e)) allowing dynamic assessment of enhancement as opposed to a ‘snapshot’ assessment on CECT. The cyst was classified as Bosniak III on both CECT and CEUS.

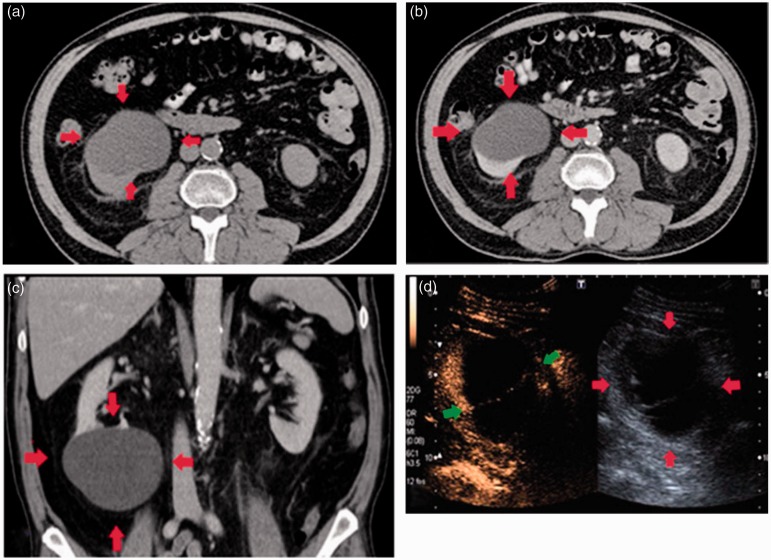

Figure 4.

Unenhanced axial CT scan (a) showing a cystic lesion, indicated by red arrows. Enhanced axial CT scan (b). Enhanced coronal CT scan (c). Unenhanced US showing increased peripheral vascularity of the lesion on Doppler imaging (d), but no blood flow within cyst. CEUS images of the lesion ((e) and (f)) showing considerable intracystic enhancement with conspicuous septa. This was classified as Bosniak IV cyst both on CECT and CEUS.

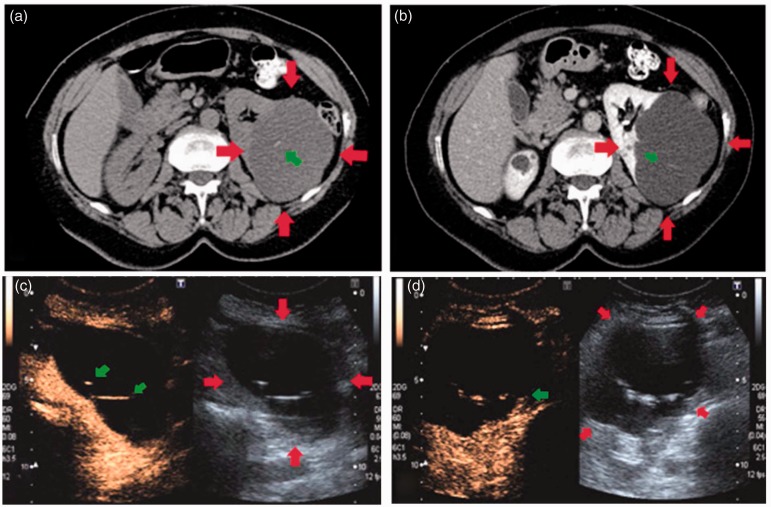

Figure 1.

CT scan of a cyst indicated by red arrows: unenhanced axial scan (a), enhanced axial scan (b) and enhanced coronal scan (c). Dual screen CEUS scan of the same cyst (d) with unenhanced greyscale image on the right and contrast-enhanced image on the left. Green arrows indicate septation seen within the cyst on US, but not CECT, demonstrating the superior spatial resolution of US. The cyst was classified as Bosniak I on CECT and Bosniak II on CEUS.

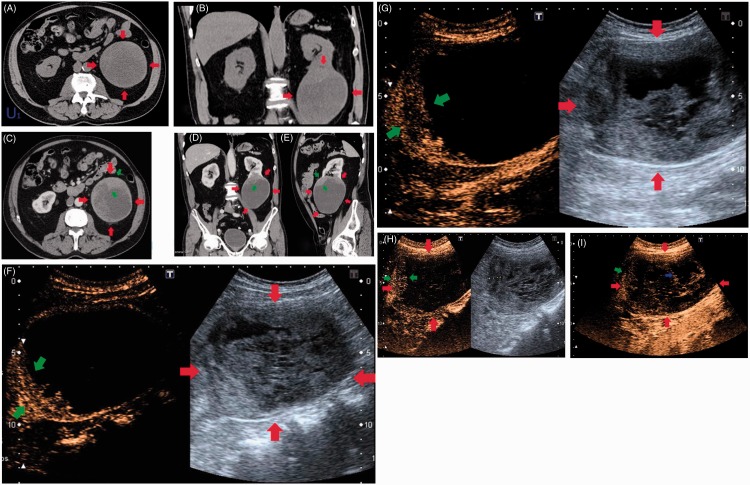

Figure 5.

Axial (A) and coronal (B) unenhanced CT scans demonstrating a large complex cyst (between red arrows). Corresponding enhanced CT axial (C), coronal (D) and sagittal (E) sections through the cyst demonstrate some enhancement within the cyst (green arrows). CEUS of the same cyst (F) with grey-scale image on the right showing internal echoes, and simultaneous contrast-enhanced image on the left showing enhancement of a thickened and trabeculated cyst wall (green arrows) taken at 1 min 3 s following SonoVue injection. Image (G) taken at 1 min 40 s shows enhancement of the thickened wall on CEUS. Image (H) shows measurement of the cyst wall thickness (between green arrows; 15 mm); note further gradual enhancement throughout the contents of the cyst. Image (I) taken in a very late phase shows inhomogenous enhancement throughout the whole of the cyst with the wall (green arrows) being less prominent, and areas of non-enhancement possibly due to necrosis within the cyst shown by the blue arrow. This was classified by observer 1 as Bosniak III on CECT, and Bosniak IV on CEUS. The other observer classified it as Bosniak IV on both modalities. Histology of the lesion demonstrated a clear cell carcinoma.

Observer variation

There was complete agreement in Bosniak classification between both modalities and both observers in six cysts (11.8%) (Tables 2 and 3). For observer 1, there was agreement in Bosniak classification on both modalities in 24 of 51 cysts (47%) which was classed as a fair agreement (κ 0.33, 95% CI: 0.10, 0.56), p = 0.13. For observer 2, there was agreement in Bosniak classification on both modalities in 17 of 51 cysts (33%), with invalid weighted κ coefficient.

Table 2.

Comparison of Bosniak classifications between modalities for observer 1

| Observer 1 |

CECT |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEUS | I | II | IIF | III | IV | Total |

| I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 6 | 19 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| IIF | 2 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| III | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 8 | 32 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 51 |

Table 3.

Comparison of Bosniak classifications between modalities for observer 2

| Observer 2 |

CECT |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEUS | I | II | IIF | III | IV | Total |

| I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| IIF | 2 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 13 |

| III | 1 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 20 |

| IV | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| Total | 7 | 20 | 14 | 6 | 4 | 51 |

There was moderate agreement between both observers in Bosniak classification for CECT scans (κ 0.45, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.64), p = 0.26. Agreement between both observers in Bosniak classification for CEUS scans gave an invalid weighted κ coefficient. In 16 out of 51 cysts (31%), both observers gave CEUS a higher Bosniak classification than for the corresponding CECT scans (Tables 4 and 5). Conversely, there was only one cyst (2%) where both observers gave CECT a higher Bosniak classification than for the corresponding CEUS.

Table 4.

Comparison of Bosniak classifications between observers for CECT

| CECT |

Observer 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observer 1 | I | II | IIF | III | IV | Total |

| I | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| II | 2 | 16 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 32 |

| IIF | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| III | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 7 | 20 | 14 | 6 | 4 | 51 |

Table 5.

Comparison of Bosniak classifications between observers for CEUS

| CEUS |

Observer 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observer 1 | I | II | IIF | III | IV | Total |

| I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 0 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 29 |

| IIF | 0 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 13 |

| III | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 0 | 11 | 13 | 20 | 7 | 51 |

Histopathological reports and follow-up

Pathological reports were only available for three cysts, all of which had malignant histology. Two were found to be papillary cell carcinoma and one was a clear cell carcinoma (Figure 5). Observers agreed on CEUS classification of all three cysts as being surgical and on the majority of CECT classification as being surgical (observer 1 – two surgical, one non-surgical (Bosniak IIF); observer 2 – all three surgical). Two patients with cysts deemed malignant on imaging were not suitable for surgery. Twenty-two cysts remained stable on follow-up of 6–24 months duration. The remaining 27 cysts were classed as benign by radiologists reporting the gold standard CT outside of the study protocol.

Patient questionnaires

Forty-four out of the 46 patients completed a patient questionnaire, with two patients leaving the department before being handed one; staff reported no adverse effects from the use of either type of contrast in these two patients. No major adverse effects were reported following the use of Omnipaque 300. Common minor side effects were reported by 28 of the 44 patients (63.6%) following the use of Omnipaque 300, and included pain at the injection site, headache, nausea, a burning sensation in the bladder, a feeling of warmth all over. Following the use of SonoVue, no adverse effects were reported (minor or major). About 81.8% of respondents (36/44) expressed a preference for the CEUS examination instead of CECT and the remaining 18.2% of respondents (8/44) expressed no preference, stating that they could have either examination. No patient expressed preference for CECT instead of CEUS. Patients were also asked to score each examination out of 10 for their satisfaction. The scores for CEUS were higher than CECT, with average scores being 9.6 and 7.5, respectively, reflecting expressed preference for CEUS.

Discussion

There was at best moderate agreement simultaneously between observers and between modalities in our prospective study. Retrospective studies have reported higher levels of interobserver agreement.16,17 The only other prospective study comparing Bosniak classification using CECT and CEUS by Ascenti et al.18 reported good interobserver agreement (κ 0.79) among three readers of 44 consecutive complex cysts, and subsequently recommended CEUS as appropriate for renal cyst classification with the Bosniak system.

The limitation of their study, similarly to our work, was the lack of pathological correlation in the majority of cysts. Of note is the fact that the level of interobserver agreement for the gold standard of CECT in their study was exceptionally high (κ 1.00), whilst in our study it was moderate, which in turn is in line with a rather more modest reported level of agreement in other studies, for instance in a study by Siegel et al.13 being only 59%. Quaia et al.16 reported on agreement between pairs of three observers in retrospectively classifying the lesions as malignant or benign (rather than assigning an exact Bosniak classification). For CEUS, the agreement varied widely, with κ 0.81 for observers 1 and 2, κ 0.67 for observers 2 and 3, but only κ 0.13 for observers 1 and 3. For CECT, κ was within the moderate range, at 0.58, 0.59 and 0.55, respectively.

Park et al.17 also compared CECT and CEUS in the retrospective assessment of cystic renal masses in 31 patients, reporting agreement between CECT and CEUS in 76% of cases. They did not look at interobserver variability, with grading performed by the two observers in consensus. In addition, their study was subject to observer bias as the CEUS examinations were analysed after the CECT had been reviewed, whilst in our study both observers were blinded to the results of the other modality.

The largest margin of disagreement, as expected,22,23occurred in our study between Bosniak IIF and III categories, where considerable experience is required to interpret borderline complex features (septation, soft tissue nodules, calcification and post-contrast enhancement).

In 31% of complex cysts, in our study both observers assigned a higher Bosniak classification on the CEUS examination than on the CECT examination. In the prospective study by Ascenti et al.18 in all six (14%) of the cases where there was disagreement in Bosniak classification between CECT and CEUS, CEUS gave a higher classification than CECT. This highlights the fact that CEUS has higher sensitivity than CECT to enhancement and presence of complex features within a cyst, frequently resulting in an upgraded Bosniak classification compared to CECT.16–18,20,22 Although CEUS may show enhancement within intracystic septations which is absent on CECT, minimal septal enhancement is not necessarily thought to be indicative of malignancy and may be seen in benign lesions.16,22 On the other hand, there have been documented cases where a solid enhancing nodule, proving to be malignant, was visualised on CEUS, but missed on CECT.16 In our study, a patient who was found to have papillary cell carcinoma histologically confirmed following surgery, was given a Bosniak classification IIF by one observer (non-surgical, but requiring follow-up) on CECT, but showed considerable enhancement of a nodule and cyst wall on CEUS, correctly indicating a higher index of suspicion for malignancy. This lesion would have, therefore, been given a misdiagnosis on CECT (by one of the observers) with a possible delay or omission of surgery.

It has been postulated that CEUS should therefore have its own classification of renal cysts.16,22

Enhancement remains a subjective assessment for observers, even on CECT examinations, and it is difficult to measure CT density Hounsfield units in thin septa or small nodules. Quaia et al.16 describe the lack of quantitative measurement as a limitation of CEUS and state that its use would allow a more reproducible assessment of intra-cystic enhancement. It was also difficult to assess intracystic anatomy with CEUS when dense mural calcification was present, due to acoustic shadowing obscuring the detail.

CEUS does have the same limitations as baseline ultrasound. One patient in our study was given a higher Bosniak classification on CECT (IIF/III) than on CEUS (II). This patient had a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 39.4 making their cyst very difficult to assess sonographically. It was found to be a hyperdense cyst on CECT with an average pre-contrast density of 64 HU and post-contrast density of 109 HU. CEUS showed an anechoic cyst with a single septation, making this a Bosniak II cyst with no apparent enhancement after administration of contrast. This lesion was stable on surveillance scans and is thought to be benign.

No minor or major adverse effects were reported following the use of US contrast (SonoVue), whilst 63.6% of questionnaire respondents suffered minor side effects following the use of CT contrast (Omnipaque 300). Pain at the injection site and a feeling of warmth are effects attributable to hyperosmolality of the injection,24,25 although the much smaller injection volume used for CEUS (2.4 ml) compared to CECT (100 ml) may have also been a contributory factor. Bellin et al.26 list use of a power injector, the large volume of contrast medium and high osmolar contrast medium as risk factors for contrast medium extravasation injury (and subsequent pain), which explains increased incidence of pain at the injection site on CECT examinations compared to CEUS examinations.

The majority of patients (81.8%) preferred CEUS to CECT, with remaining patients expressing no preference. This high level of patient satisfaction with CEUS agrees with a study by Molina et al.27 where 98.2% of patients expressed a good or very good rating for patient satisfaction with CEUS.

There were limitations to our study. CEUS was seldom used in our department prior to this study outside of the more established liver lesion characterisation, resulting in the observers’ limited experience when assessing the scans. This may have been a major contributory factor in the agreement between the observers being lower than in other published studies.

The study was prospective and carried out over a limited period of time, which did not allow for the final outcome for some patients to be obtained and thus the resulting accuracy of the scans. Renal cell carcinomas have a slow growth rate,18 and as such, IIF lesions require a follow-up period of up to five years to prove benignity.3 Pathological results were only available for three patients, giving a very small number of true positive findings in this study in terms of malignancy. Patients were recruited based mostly on sonographic findings. Lesions which may have been interpreted as simple on CT scans as the referral modality and hence omitted from the study, may have appeared complex on ultrasound. This occurred with several patients in the study, where at least one observer gave the CT appearance a Bosniak I classification.

Conclusions

CEUS is a feasible tool in the evaluation of complex renal cysts in clinical practice although continuing experience is necessary to improve at best moderate diagnostic accuracy in the hands of relatively inexperienced observers. In particular, application of grade IIF and III of Bosniak classification, especially to CEUS, proves difficult, being dependent on the observer’s experience and personal opinion. CEUS upgrades CECT Bosniak classification due to its high sensitivity to contrast enhancement. With increasing experience, we recommend CEUS for follow-up of complex renal cysts (IIF) to avoid radiation and nephrotoxicity. We also propose a one stop CEUS assessment of complex renal cysts following their incidental finding on ultrasound examinations performed for unrelated indications to alleviate patient anxiety whilst awaiting a definitive diagnosis. Patients with contraindications to CECT should also have complex renal cyst assessment performed by CEUS.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dan Lythgoe for help with statistical analysis.

Declarations of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Bracco, Milan, Italy.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the local Research Ethics Committee (project no. 09/H1002/39). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Guarantor

JMW

Contributorship

MMR researched literature and designed the study. MMR performed CEUS examinations. JMW and AN carried out image analysis. MMR did the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JMW and MMR wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Laucks SP, McLachlan MSF. Aging and simple cysts of the kidney. Brit J Radiol 1981; 54: 12–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang C, Kuo J, Chang W, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of simple renal cysts. J Chin Med Assoc 2007; 70: 486–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel GM, Bosniak MA. Follow-up CT of moderately complex cystic lesions of the kidney (Bosniak Category IIF). Amer J Roentgenol 2003; 181: 627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terada N, Ichioka K, Matsuta Y, et al. The natural history of simple renal cysts. J Urol 2002; 167: 21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeman RK, Cronan JJ, Rosenfield AT, et al. Imaging approach to the suspected renal mass. Radiol Clin North Am 1985; 2: 503–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang J, Chen Y, Zhou Y, et al. Clear renal cell carcinoma: Contrast-enhanced ultrasound features relation to tumor size. Eur J Radiol 2010; 73: 162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayson M, Sanders H. Increased incidence or serendipitously discovered renal cell carcinoma. Urology 1998; 51: 203–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porena M, Vespasiani G, Rosi P, et al. Incidentally detected renal cell carcinoma: role of ultrasonography. J Clin Ultrasound 1992; 20: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paspulati RJ, Bhat S. Sonography in benign and malignant renal masses. Radiol Clin North Am 2006; 44: 787–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosniak MA. The current radiological approach to renal cysts. Radiology 1986; 158: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosniak MA. Diagnosis and management of patients with complicated cystic lesions of the kidney. Amer J Roentgenol 1997; 169: 819–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graumann O, Osther SS, Osther PJ. Characterisation of complex renal cysts: a critical evaluation of the Bosniak classification. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2011; 45: 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel CL, McFarland EG, Brink JA, et al. CT of cystic renal masses: analysis of diagnostic performance and interobserver variation. Am J Roentgenol 1997; 169: 813–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correas J, Claudon M, Tranquart F, et al. The kidney: imaging with microbubble contrast agents. Ultrasound Quarter 2006; 22: 53–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartman DS, Choyke PL, Hartman MS. A practical approach to the cystic renal mass. Radiographics 2004; 24: 101–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quaia E, Bertolotto M, Cioffi V, et al. Comparison of contrast-enhanced sonography with unenhanced sonography and contrast-enhanced CT in the diagnosis of malignancy in complex cystic renal masses. Amer J Roentgenol 2008; 191: 1239–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park BK, Kim B, Kim SH, et al. Assessment of cystic renal masses based on Bosniak classification: Comparison of CT and contrast-enhanced US. Eur J Radiol 2007; 61: 310–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ascenti G, Mazziotti S, Zimbaro G, et al. Complex cystic renal masses: characterization with contrast-enhanced US. Radiology 2007; 243: 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Israel GM, Hindman N, Bosniak M. Evaluation of cystic renal masses: comparison of CT and MR imaging by using the Bosniak classification system. Radiology 2004; 231: 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clevert DA, Minaifar N, Weckbach S, et al. Multislice computed tomography versus contrast-enhanced ultrasound in evaluation of complex cystic renal masses using the Bosniak classification system. Clin Hemorheol Microcirculat 2008; 39: 171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbin ML, Lockhart ME, Barr RG. Renal imaging with ultrasound contrast: current status. Radiol Clin North Am 2003; 41: 963–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang EK, Macchia RJ, Gayle B, et al. CT-guided biopsy of indeterminate renal cystic masses (3 and 2F): accuracy and impact on clinical management. Eur Radiol 2002; 12: 2518–2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chopra P, Smith H. Use of radiopaque contrast agents for the interventional pain physician. Pain Physician 2004; 7: 459–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf WJ. Evaluation and management of solid and cystic renal masses. J Urol 1998; 159: 1120–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellin MF, Jakobsen JA, Tomassin I, et al. Contrast medium extravasation injury: guidelines for prevention and management. Eur Radiol 2002; 12: 2807–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolau Molina CN, Fontanilla Echeveste TF, Del Cura Rodriguez JL, et al. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in daily clinical practice: a multicenter study in Spain. Radiologia 2010; 52: 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Israel GM, Bosniak MA. How I do it: evaluation renal masses. Radiology 2005; 236: 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]