Abstract

Identification of reliable and robust biomarkers is crucial to enable early diagnosis of Parkinson disease (PD) and monitoring disease progression. While imperfect, the slow, chronic 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced non-human primate animal model system of parkinsonism is an abundant source of pre-motor or early stage PD biomarker discovery. Here, we present a study of a MPTP rhesus monkey model of PD that utilizes complementary quantitative iTRAQ-based proteomic, glycoproteomics and phosphoproteomics approaches. We compared the glycoprotein, non-glycoprotein, and phosphoprotein profiles in the putamen of asymptomatic and symptomatic MPTP-treated monkeys as well as saline injected controls. We identified 86 glycoproteins, 163 non-glycoproteins, and 71 phosphoproteins differentially expressed in the MPTP-treated groups. Functional analysis of the data sets inferred the biological processes and pathways that link to neurodegeneration in PD and related disorders. Several potential biomarkers identified in this study have already been translated for their usefulness in PD diagnosis in human subjects and further validation investigations are currently under way. In addition to providing potential early PD biomarkers, this comprehensive quantitative proteomic study may also shed insights regarding the mechanisms underlying early PD development. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: Neuroproteomics: Applications in neuroscience and neurology.

Keywords: Parkinson disease; glycoproteomics; phosphoproteomics; 1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP); Macaca mulatta; putamen

Introduction

Parkinson disease (PD) is a chronic, progressively debilitating neurodegenerative disorder affecting 1–2% of persons over the age of 65 years worldwide [1, 2]. It is currently incurable, and treatment attempts are complicated by the advanced loss of neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) present even at the earliest clinical manifestation of motor dysfunction [1–4]. Although PD has a prolonged prodromal phase during which non-motor clinical features as well as physiological abnormalities may be present [5], current PD diagnosis still largely relies on the more apparent classical clinical motor symptoms, which occur at later stages of the disease. At present, few diagnostic tools for unequivocal identification of PD patients at early stages are available [2, 6, 7]. This prevents early treatment that would potentially improve prognosis and impedes the progress of research toward treatments aimed at the preclinical population. Furthermore, there is currently no effective biomarker to predict or monitor PD progression.

Clinical premotor features, including olfactory disturbance, excessive daytime sleepiness, rapid eye movement behavior disorder, constipation, and depression, have been strongly linked to PD [5]. However, none of these signs alone are specific and sensitive enough for identifying premotor PD, thus limiting their clinical utilities to identifying high-risk individuals. The most sensitive tests developed to date as early PD biomarkers are based on imaging modalities, which can detect functional and structural abnormalities before the onset of motor dysfunction [6, 7]. However, the usefulness of neuroimaging techniques is limited by high cost, limited accessibility, and is subject to confounding factors such as medication and compensatory responses. Thus, a current major focus of early PD biomarker research is to identify biochemical marker candidates in the brain or body fluids, which might reflect the state of the disease. We have already investigated several potential cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) markers (known to be important in sporadic PD) in a cohort of symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects carrying one of the strongest risk factors for PD - the leucine rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) gene mutations, and identified that some CSF protein levels correlated with the progressive loss of striatal dopaminergic functions as determined by positron emission tomography (PET) [8, 9]. The emergence of several –omics techniques, including transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, has also greatly enhanced our ability to identify novel pathways and potential biomarkers for PD [7, 10, 11].

In the current study, using a non-human primate animal model of parkinsonism [12–14] and advanced unbiased proteomic profiling technologies, we intended to further identify key brain region proteins that are altered during the early disease stages and may be used as early PD biomarker candidates. In contrast to previous proteomic profiling studies in rodent models [15–21], we used 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) administered to monkeys via a slow intoxication protocol to produce a gradual development of nigral and striatal lesions mimicking the typical, chronic evolution of PD in humans [12, 13]. Additionally, we selectively enriched the glycoproteins and phosphoproteins and compared their proteomic profiles in the putamen samples collected at different states that mimic early stage parkinsonism, where no motor symptoms are apparent (asymptomatic) and later stage parkinsonism, where the cardinal motor symptoms are apparent (symptomatic). Differentially expressed proteins were identified between these states that were verified by behavioral, neuroimaging, and postmortem immunohistological measurements.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental design

Fifteen adult female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta, 4.5–8.5 kg) from the Yerkes National Primate Research Center colony were used in this study, in accordance with the guidelines from the National Institutes of Health. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University (IACUC#: 256-2007Y, date: 08/2007). The animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room and exposed to a 12-h light/dark cycle. They were fed twice daily with monkey chow supplemented with fruits or vegetables. The animals had free access to water.

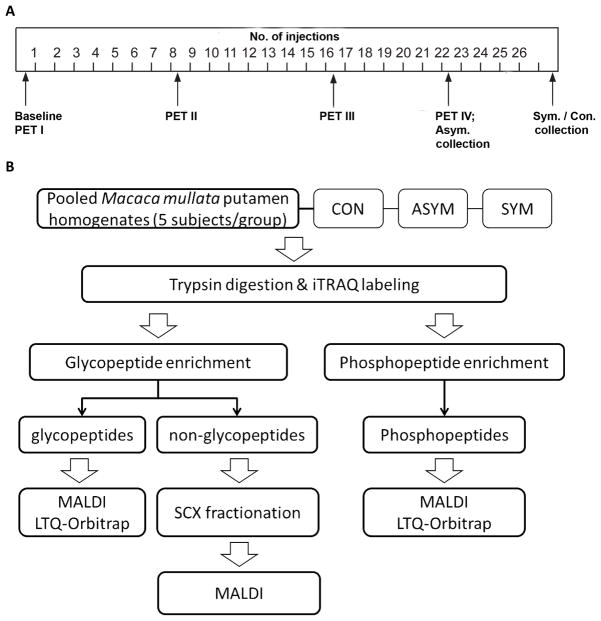

The 15 monkeys were divided into three groups. After collection of baseline behavioral and 2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-chlorophenyl)-8-(2-[18F]-fluoroethyl)-nortropane (18F-FECNT) PET imaging data using methods described previously [12, 13], these monkeys received a series of weekly intramuscular injections of either saline (Group 1, n=5) or MPTP (0.2–0.5 mg/kg body weight; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; Groups 2 and 3, n=5 for each group) (Fig. 1A). The animals were continuously monitored via behavioral observations and PET scans. After about 20–22 weeks of MPTP treatment, all Group 3 animals progressively developed moderate to severe parkinsonian symptoms according to the rating scale described previously [12, 13]. Group 2 animals, on the other hand, were sacrificed before any significant change in their motor behavior relative to baseline measurements appeared. At the termination of the experiment, part of the brain was frozen for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. The remaining parts were used for the postmortem dopaminergic cell counts and striatal densitometry measurement of dopamine transporter (DAT) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactivity as previously described [12, 13, 22].

Figure 1. Study design.

(A) MPTP treatment schedule. (B) Experimental scheme for comprehensive proteomic profiling of the glycoproteome and phosphoproteome. ASYM, asymptomatic MPTP-treated monkeys; CON, saline-injected controls; PET, positron emission tomography; SCX, strong cation exchange; SYM, symptomatic MPTP-treated monkeys.

Sample preparation

About 100 mg of frozen putamen tissue was quickly thawed on ice and homogenized using a glass-Teflon homogenizer in a lysis buffer [7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 65 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 2% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylamino]-1-propane sulfonate (CHAPS), and 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC; Cat.# P2714, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA; prepared in 10 mL of H2O) for glycopeptide enrichment, or 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 μM okadaic acid, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 × Halt phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce/Thermo, Rockford, IL, USA), 1% (v/v) PIC in 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES; pH 7.5) for phosphopeptide enrichment]. The sample was further homogenized using a probe sonicator (microtip) with 10–20 pulses at low setting. The mixture was then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes (4°C) and the supernatant was transferred into a new centrifuge tube. For glycopeptide enrichment, proteins were precipitated from the supernatant by the addition of one volume TCA and eight volumes cold acetone and incubation at −20°C for 1 hour. The protein pellets were recovered by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes and 4°C and solubilized in 200 μL of digestion buffer [8M urea, 0.1% SDS and 2% Triton X-100 in 0.5 M triethyl ammonium bicarbonate buffer (TEAB), pH 8.5]. For phosphopeptide enrichment, the homogenate after sonication was used directly. The total protein concentration was estimated using a bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA; Pierce/Thermo). Equal amounts of protein from individual samples of control (5 cases), asymptomatic (5 cases), and symptomatic (5 cases) were pooled to create control (CON), asymptomatic (ASYM), and symptomatic (SYM) groups, respectively. At least three replicate pools were made for each group. A master pool sample was also created by combining equal amounts of all individual samples.

iTRAQ labeling

Labeling of peptides using the 4-plex iTRAQ reagent multiplex kit (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) was performed as previously described [23], with minor modifications. Briefly, 100 μg of total protein from each pooled sample was reduced using 5 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) at 37°C for 1 hour. The mixture was then alkylated using 10 mM S-Methyl methane thiosulfonate (MMTS) for 10 minutes at room temperature. The sample was diluted 8 times with 0.5 M TEAB. Trypsin (Promega, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA) was then added at a 1:20 (w/w) enzyme to protein ratio and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. Then, the same amount of trypsin was added and the incubation continued for 14–16 hours. Digested samples were evaporated to ~50 μL using a CentriVap concentrator (Labconco Inc, Kansas City, MO, USA) and then labeled with different iTRAQ reagents (CON – 114, ASYM – 115, SYM – 116, master pool – 117) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The labeled samples from the four groups were pooled together and desalted using a C18 cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) before glycopeptide or phosphopeptide enrichment.

Glycopeptide enrichment

Glycopeptide enrichment in pooled samples was performed using hydrazide resin as previously described [23, 24]. In brief, iTRAQ-labeled peptides were oxidized with 10 mM sodium periodate in an oxidation buffer (100 mM sodium acetate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 5.5) in the dark at room temperature for 1 hour with gentle mixing on a rotating shaker. The sample was then desalted through a C18 cartridge and collected in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/80% acetonitrile (ACN). For each sample, 600 μL of hydrazide resin (Affi-Gel Hz Hydrazide Gel, Cat.# 153-6047, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA; 50% slurry) was washed and equilibrated in 0.1% TFA/50% ACN. Coupling of glycopeptides to the resin was then performed at room temperature for 22–24 hours. The resin was recovered by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 minutes and then washed three times with 1.5 M NaCl, three times with 80% ACN, three times with 100% methanol, three times with deionized water, and finally three times with 0.1 M NH4HCO3 (pH 8.3). All supernatants were saved and combined for non-glycoprotein MS analysis. N-linked glycopeptides were recovered from the resin by PNGase F (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) cleavage for about 48 hours at 37°C. The supernatant containing the released glycopeptides was collected, and further extraction was performed by rinsing the resin 3 times with 0.05 M NH4HCO3 (pH 8.3) and then twice with 80% ACN. The samples were desalted using C18 cartridges before further analysis.

The non-glycopeptide mixture generated from the glycopeptide enrichment was further fractionated by strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography before MS analysis. The sample was reconstituted in 1 mL buffer A (5 mM KH2PO4 and 25% ACN, pH 2.7–3.0) and fractionated using a PolySulfo-ethyl A (200 × 2.1 mm × 5-μm, 300 A) column (PolyLC, Columbia, MD, USA) on a Biologic Duo-Flow LC system (Bio-Rad). The peptides were separated with a linear gradient of 0% buffer B (5 mM KH2PO4, 25% ACN, 600 mM KCl, pH 2.7–3.0) to 100% B for 125 min at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. Fractions were collected and pooled to give approximately equal mass of total peptide per fraction based on a UV trace. Eight to nine SCX pools were made for each sample and desalted using C18 cartridges.

Phosphopeptide enrichment

Phosphopeptides were enriched using titanium dioxide (TiO2) affinity purification adapted from a published protocol [25]. Phosphopeptides in labeled samples were allowed to bind to TiO2 spin tips from a TiO2 Phosphopeptide Enrichment and Clean-up Kit (Pierce/Thermo), eluted from the spin tip, and cleaned using graphite spin columns (Pierce/Thermo) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were dried and resuspended in 0.5% TFA before MS analysis.

Mass spectrometry and protein quantification

For MALDI TOF/TOF tandem MS analysis, all three fractions (non-glycopeptides, glycopeptides, and phosphopeptides) were separated on a reversed-phase (RP) LC (Ultimate HPLC system, LC Packing/Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) coupled to a Probot™ spotting system (LC Packing/Dionex) using a linear gradient from 5 to 90% mobile phase B (80% ACN and 0.1% TFA in HPLC water) and mobile phase A (2% ACN and 0.1% TFA in HPLC water) for 120 min at a flow rate of 0.4 μL/min. The eluted fractions were mixed with matrix solution (recrystallized α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid, 7 mg/ml in 60% ACN and 2.6% ammonium citrate) at a 1:1 ratio and spotted onto a stainless MALDI plate. The spotted sample plates were analyzed using a 4800 Plus MALDI TOF/TOF™ (AB SCIEX) with a selected mass range of 800–3500 m/z and signal to noise (S/N) ratio greater than 50. MS/MS mass spectral data were analyzed using ProteinPilot software version 4.0 (AB SCIEX) referencing a M. mulatta database retrieved from UniProt (April 2012) with the following search parameters: MMTS for cysteine alkylation, trypsin specificity allowing up to 2 missed cleavages; biological modification, amino acid and substitutions were set for ID focus. For phosphopeptide-enriched samples, phosphorylation emphasis was used. The false discovery rate (FDR) of the identified protein was set to <5% and protein confidence greater than 95% was used with base correction. Background correction was considered to normalize the data. For non-glycoproteins, at least two peptide matches were considered for positive protein identification.

The glycopeptide and phosphopeptide fractions were also analyzed using a LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). Peptides were separated online with 75 μm i.d. × 20 cm home-packed fused silica columns (100 A Magic C18AQ: Michrom Bioresources, Auburn, CA, USA) using a nanoAcquity UPLC (Waters) with a 125 min 5–90 % acetonitrile/water gradient containing 0.1 % formic acid. Typical instrument settings were used and the top 20 most abundant ions were subjected to high-energy collision-induced dissociation (HCD) with normalized collision energy of 25%. All analyses were operated in positive ionization mode and the automatic gain control (AGC) was optimized to maintain constant ion populations. MS/MS mass spectral data were uploaded to SEQUEST (v27) and searched against the M. mulatta database and protein identifications were filtered by Peptide Prophet. The deamidation (+0.984 Da) of asparagine (N) was set as a dynamic modification as a result of deglycosylation with PNGase F; the threonine (T), tyrosine (Y), and serine (S) residues were set as being phosphorylated (+79.977 Da). All methionines (M) were allowed to be oxidized and methylthiolation (+45.988 Da) of cysteine (C) was considered as a static modification.

Protein (iTRAQ) quantification was expressed as a ratio with the CON levels (iTRAQ 114) as the denominator. A protein was considered differentially expressed if the iTRAQ ratio (e.g., ASYM/CON or SYM/CON) was ≥1.20 (increased) or ≤0.83 (decreased) [26].

Protein function and pathway analysis

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed on proteins associated with changes using the online AgBase-Goanna resource (version 2.0; http://agbase.msstate.edu/cgi-bin/tools/GOanna.cgi), which is a powerful homology-based approach for GO enrichment analysis [27], against the Agbase-UniProt database.

Results

MPTP treatment effects

Consistent with our previous findings [12, 13, 22], all MPTP-treated monkeys in the symptomatic (SYM) group displayed moderate to severe parkinsonian symptoms after 20–22 weeks of MPTP treatment, while monkeys in the saline control (CON) and asymptomatic (ASYM) groups did not show significant changes in their parkinsonism rating scores at the termination of the experiment. The different behavioral responses were correlated with the 18F-FECNT uptake in all striatal regions of interest (see representative PET images in Supplementary Fig. 1) as reported previously [12, 13].

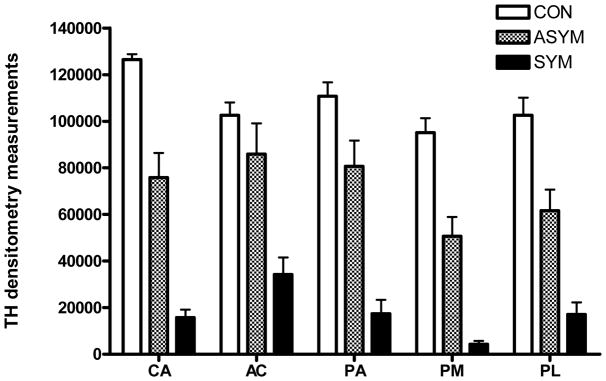

Postmortem TH immunohistochemistry studies in the animals in the SYM group showed an almost complete loss of TH immunoreactivity in the dorsal striatum (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Animals in the ASYM group displayed a less severe decrease in striatal TH immunoreactivity in all regions of interest compared with the SYM monkeys. The degree of TH depletion in all MPTP-treated monkeys was most severe in the post-commissural putamen regions of interest (putamen/motor, putamen/limbic) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Similar findings were found in striatal tissue immunostained for DAT, and significant depletion in the number of TH-immunoreactive neurons was also observed in the SNpc in MPTP-treated monkeys (Supplementary Fig. 3 and data not shown), confirming our previous observations [12, 13].

Figure 2. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) immunoreactivity in control and parkinsonian monkeys.

Average postmortem densitometry measurements are shown for different striatal regions in saline-injected controls (CON), asymptomatic (ASYM) and symptomatic (SYM) MPTP-treated monkeys. AC, accumbens; CA, caudate nucleus; PA: putamen associative (pre-commissural putamen); PL: putamen limbic (ventral post-commissural putamen); PM, putamen sensorimotor (dorsal post-commissural putamen).

Glycoprotein and non-glycoprotein profiling in asymptomatic and symptomatic MPTP monkeys

Given the significant changes observed in the striatum, particularly the putamen regions, in MPTP-treated monkeys, we focused the quantitative proteomic profiling on the putamen in this study, aiming to identify the proteins altered during the early disease stage before the apparent symptoms appeared (see Fig. 1B for the proteomic experimental design). Firstly, to maximize the chance of successful identification of proteins, particularly low abundant ones, we employed the commonly used hydrazide capture method [28] to enrich N-glycoproteins and separate proteins into the glyco- and non-glyco-fractions. Peptide and protein identification was accepted when the confidence was equal or greater than 95% and the FDR was less than 5%. Relative quantification was obtained through iTRAQ labeling. Samples were analyzed, at a minimum, in triplicates. Proteins identified at least twice in the experiments were counted in this study.

MS analysis of the iTRAQ-labeled glycopeptide-enriched samples provided a total of 295 glycopeptide identifications corresponding to 222 glycoproteins (Supplementary Table 1A and 1B). MALDI-TOF/TOF and LTQ-Orbitrap XL (with HCD) platforms generated partially overlapping but otherwise complementary results, in a manner similar to previous reports [29–31]. The MALDI-TOF/TOF system might perform slightly better to produce intense and reproducible iTRAQ reporter ions, but it appeared that reasonably accurate and compatible results can also be obtained on the LTQ-Oribitrap XL system (data not shown). Thus we combined the two sets of data to increase the protein and proteomic coverage.

Among the identified glycoproteins, 86 of them displayed at least 20% changes in either the asymptomatic or the symptomatic MPTP-treated group compared to the control group (see a complete list in Supplementary Table 2A). 27 of them showed significant (≥50%) early changes in the asymptomatic group (Table 1). Notably, some proteins displayed progressive changes as the disease advanced; for example, the levels of F7FY86_MACMU (ITAV_HUMAN, integrin alpha-V), G7N2R8_MACMU (SIRB1_HUMAN, signal-regulatory protein beta-1), and F6XVJ3_MACMU (HYOU1_HUMAN, hypoxia up-regulated protein 1) progressively increased in asymptomatic and symptomatic monkeys.

Table 1.

Selected altered glycoproteins identified in the MPTP monkey model

| Accession no. | Name | ASYM:CON* | SYM:CON* | Human homolog |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F7HJ53_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 50.28 | 50.19 | PGCB_HUMAN |

| F6UWH5_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) | 44.45 | 0.60 | PTPR2_HUMAN |

| G7N0R4_MACMU | Dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2 | 21.63 | 22.52 | DPYL2_HUMAN |

| F6Y0V7_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) | 21.43 | 10.44 | LAMP1_HUMAN |

| G7NIM4_MACMU | Contactin-associated protein 1 | 20.85 | 18.57 | CNTP1_HUMAN |

| F7C5T5_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 19.85 | 16.64 | CSPG2_HUMAN |

| F7CT46_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 18.98 | 2.14 | TPBG_HUMAN |

| F7G512_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 18.90 | 18.20 | NCAN_HUMAN |

| F7FA05_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) | 15.43 | 12.14 | FOLH1_HUMAN |

| G7NNG7_MACMU | Brain link protein 2 (Fragment) | 11.45 | 6.86 | HPLN4_HUMAN |

| F7AV81_MACMU | Hemoglobin beta chain | 4.42 | 0.43 | HBB_HUMAN |

| F6ZXF7_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 3.94 | 2.17 | B9EK55_HUMAN |

| G7N2R8_MACMU | Signal-regulatory protein beta-1 | 3.68 | 5.78 | SIRB1_HUMAN |

| F7HGN6_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 3.13 | 2.14 | DPP6_HUMAN |

| G7MNJ0_MACMU | Putative uncharacterized protein (Fragment) | 2.82 | 1.50 | DPP6_HUMAN |

| G7NQC3_MACMU | Hemoglobin alpha chain | 2.13 | 0.40 | HBA_HUMAN |

| F7GZA4_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 2.00 | 1.33 | OMGP_HUMAN |

| F6XVJ3_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 1.94 | 2.65 | HYOU1_HUMAN |

| F6QEE7_MACMU | ADP-ribosyl cyclase 1 | 1.80 | 1.03 | CD38_HUMAN |

| F7FY86_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) | 1.76 | 5.56 | ITAV_HUMAN |

| G7MV77_MACMU | Proteoglycan link protein | 1.73 | 1.34 | HPLN1_HUMAN |

| F6V3K6_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 1.65 | 1.76 | NFASC_HUMAN |

| G7NNG6_MACMU | Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 3 | 1.65 | 1.74 | NCAN_HUMAN |

| F7C5S6_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 1.62 | 1.46 | CSPG2_HUMAN |

| G7NKA5_MACMU | Myelin basic protein | 1.59 | 0.73 | MBP_HUMAN |

| G7NDG2_MACMU | Lysosomal acid phosphatase | 1.52 | 1.46 | PPAL_HUMAN |

| G7N1N6_MACMU | Vimentin | 0.43 | 0.35 | VIME_HUMAN |

See a complete list of altered glycoproteins in Supplementary Table 2A.

ASYM, asymptomatic MPTP-treated monkeys; CON, saline-injected controls; SYM, symptomatic MPTP-treated monkeys.

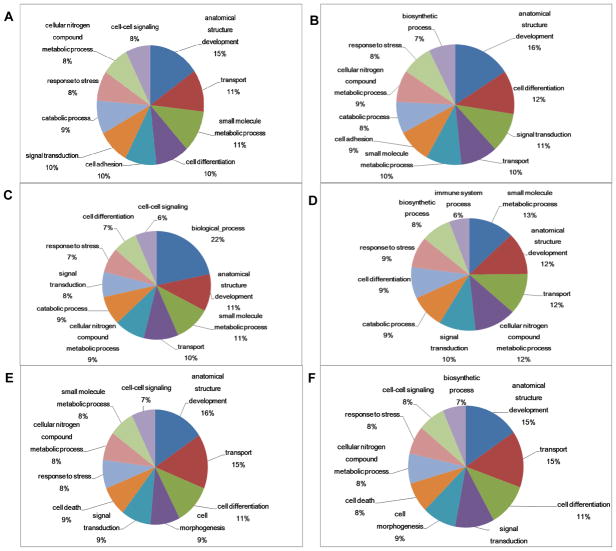

To further characterize both the total identified set of glycoproteins and the subset of altered ones, a biological function and pathway analysis was performed using the online AgBase-Goanna resource. This sequence homology based tool was chosen to maximize homologous gene/protein annotations because of the limitation of the GO annotation of M. mulatta. The results indicated that the most enriched GO categories in altered glycoproteins included anatomical structure development, small molecule metabolic processes, transport, cell differentiation, signal transduction, cell adhesion, catabolic process, cellular nitrogen compound metabolic process, response to stress, cell-cell signaling, and cell death (Fig. 3A). The main enriched categories in all identified glycoproteins were similar to those in altered glycoproteins (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Gene ontology analysis of the identified proteins.

The top 10 enriched gene ontology categories are shown for (A) altered glycoproteins (displayed ≥20% changes in either the asymptomatic or the symptomatic MPTP-treated group compared to the control group), (B) all identified glycoproteins, (C) altered non-glycoproteins, (D) all identified non-glycoproteins, (E) altered phosphoproteins, and (F) all identified phosphoproteins.

The differential expression of non-glycoproteins in asymptomatic and symptomatic putamen samples was also investigated. A strong cation exchange (SCX) was used to reduce the complexity of the samples, and each of the resulting fractions was thoroughly analyzed using LC-MALDI MS/MS in at least 3 runs. A total of 838 proteins were identified with ≥2 confidently identified peptides (Supplementary Table 3). 163 of these identified proteins displayed ≥20% changes in MPTP-treated monkeys (Supplementary Table 2B). Many of the altered proteins, including F7H5G4_MACMU (UCHL1_HUMAN, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1), F6V387_MACMU (NFASC_HUMAN, neurofascin), G7N6I0_MACMU (LDHB_HUMAN, L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain), F6ZNF3_MACMU (GFAP_HUMAN, glial fibrillary acidic protein), G7N6Q4_MACMU (CNTN1_HUMAN, contactin-1), G7MZQ9_MACMU (CALB1_HUMAN, calbindin), F7HN33_MACMU (BASP1_HUMAN, brain acid soluble protein 1), F7H4X8_MACMU (SYUG_HUMAN, gamma-synuclein), G7NGJ8_MACMU and F6WHL1_MACMU (ALDOC_HUMAN, fructose-bisphosphate aldolase C), have been implicated in neurodegeneration in PD and other diseases [32–35]. GO analysis of the identified non-glycoproteins revealed similar results as those in glycoprotein clusters, however, the immune system processes became more enriched while cell adhesion dramatically dropped down to #26 (Fig. 3C and 3D).

Phosphoprotein profiling in asymptomatic and symptomatic MPTP monkeys

The analysis of phosphoproteins by iTRAQ labeling and TiO2-affinity enrichment revealed a total of 602 unique phosphopeptides corresponding to 313 phosphoproteins (Supplementary Table 4A and 4B). Of these phosphoproteins, 71 displayed at least 20% changes in MPTP-treated monkeys (Supplementary Table 2C) and 10 of them showed significant (≥50%) early changes in the asymptomatic group (Table 2). Some of the altered phosphoproteins [e.g., F6XTG8_MACMU (Tau_HUMAN, microtubule-associated protein tau), F7H4E3_MACMU and F7F8N7_MACMU (ANK2_HUMAN, ankyrin-2), G7NB43_MACMU and F6XD34_MACMU (BIN1_HUMAN, Myc box-dependent-interacting protein 1), G7N864_MACMU and F7FN49_MACMU (S4A10_HUMAN, sodium-driven chloride bicarbonate exchanger), Q9N0X9_MACMU and F7GT55_MACMU (STX1A_HUMAN, syntaxin-1A)] have already been proposed as potential biomarkers of PD [33, 35, 36], but many others have yet to be linked to PD. Thus, we have confirmed the presence of previously reported significant PD proteins, and generated a list of novel proteins that may yield insight into potentially new mechanisms underlying PD development. GO analysis of the altered and all identified phosphoproteins (Fig. 3E and 3F) revealed that the dominant GO term associated with phosphorylated proteins is associated with cell morphogenesis when phosphoproteins were compared with glycoproteins.

Table 2.

Selected altered phosphoproteins identified in the MPTP monkey model

| Accession no. | Name | ASYM:CON* | SYM:CON* | Human homolog |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G7NQJ4_MACMU | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 3.71 | 1.30 | ALDOA_HUMAN |

| G7NGM5_MACMU | Putative uncharacterized protein | 2.66 | 0.87 | NHRF1_HUMAN |

| F7FKM0_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 2.64 | 3.28 | AKA12_HUMAN |

| G7NM84_MACMU | Putative uncharacterized protein (Fragment) | 2.32 | 1.51 | CADM1_HUMAN |

| G7NB43_MACMU | Putative uncharacterized protein | 2.09 | 2.96 | BIN1_HUMAN |

| F6XT64_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 1.94 | 1.47 | NFM_HUMAN |

| G7NKA5_MACMU | Myelin basic protein | 1.84 | 1.89 | MBP_HUMAN |

| G7NA27_MACMU | Putative uncharacterized protein | 1.69 | 1.23 | SPTB2_HUMAN |

| F7GUQ8_MACMU | Uncharacterized protein | 1.53 | 1.08 | DNJC5_HUMAN |

| G7MK67_MACMU | Putative uncharacterized protein | 0.44 | 0.68 | ARP21_HUMAN |

See a complete list of altered phosphoproteins in Supplementary Table 2C.

ASYM, asymptomatic MPTP-treated monkeys; CON, saline-injected controls; SYM, symptomatic MPTP-treated monkeys.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study represents the first large-scale proteomic analysis of striatum in the MPTP monkey model of PD. In the investigation we have identified quantitatively altered proteins in this model of parkinsonism with potential utility as early disease diagnostic biomarkers and biomarker candidates for the subtle changes that mark the progression from early to advanced stages. It should be noted that although animal models provide valuable contributions to biomarker discovery and insight as to the roles of biomarkers in the molecular circuitry and mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of PD, or neurodegeneration in general, no animal model, including the MPTP mouse models utilized in recent proteomic studies [15–21] and the MPTP monkey model used in this study, is able to faithfully replicate the complexity of PD in humans. However, this MPTP monkey model reproduces important features of idiopathic PD in humans, namely the loss of dopamine-producing neurons, reduction in striatal dopamine level, and motor abnormalities [37–40]. The slow MPTP intoxication of primates used in this study may produce a more gradual development of nigral lesion, and critical thresholds can be established distinguishing between the asymptomatic and symptomatic parkinsonian stages [12–14]. Furthermore, this model may improve on the rodent models with respect to display of significant neuronal loss in non-dopaminergic regions (e.g., the locus coeruleus [13], the raphe, the center median and parafascicular thalamic nuclei [41]) known to be affected in PD [41].

The development of high performance quantitative MS-based methods has revolutionized biomarker discovery and currently stands at the forefront in identifying relevant disease-related biomarker candidates. Although a wide array of approaches is available, stable isotope labeling techniques, including the isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) [42, 43] used in this study, are well suited in quantifying candidate biomarkers in disease versus control samples. With this strategy, highly sensitive and specific quantification with low limits of detection and quantification can be achieved. We and others have successfully implemented this approach in studies to characterize glycoproteins, and proteins generally associated with neurodegenerative disorders including PD and AD; moreover, the altered proteins identified with these techniques could be confirmed or validated using independent technologies such as Western blotting [26, 44–48]. The data presented here also suggests that LC-ESI-MS/MS and LC-MALDI-TOF/TOF could be complementary platforms when using iTRAQ technology. Employing both increases both protein and proteomic coverage over what would be obtained by either alone, particularly for complex samples.

A key advance of this investigation is that using glycopeptide and phosphopeptide enrichments along with iTRAQ labeling we have identified glycoproteins, non-glycoproteins, and phosphoproteins that are altered during the early stages in the MPTP-induced animal model system of parkinsonism; some of the identified proteins have already been linked to neurodegeneration. Glycosylation is an important and ubiquitous post-translational modification in proteins. Deregulated and aberrant protein glycosylation has been implicated in PD, Alzheimer disease (AD), and other neurodegenerative diseases [44]; and glycoproteins, which are prevalent among extracellular surface proteins and secreted proteins, are ideal sources of biomarkers. We have identified a class of glycoproteins that are highly up-regulated in putamen of asymptomatic monkeys known as proteoglycans. These glycoproteins play important roles in synaptic plasticity and serve as signaling molecules for neurite outgrowth in the central nervous system. The core proteins, brevican (PGCB), versican (CSPG2), neurocan (NCAN), and hyaluronan and proteoglycan link (HPLN4) were highly overexpressed in asymptomatic monkeys. For instance, the brevican core protein had a 50-fold enhancement in the asymptomatic group versus control and the level remained the same in the symptomatic group. Similar trends were observed in the other core proteins. Although CSPG2 and HPLN4 showed a reduction in the symptomatic group when compared to the asymptomatic group, the levels of these proteins were still significantly higher than the control group. The high levels of these glycoproteins in asymptomatic monkeys suggest that the increase of glycosylation in these proteins or their total protein levels may be an early event associated with neuronal loss and neurodegeneration.

The proteins DPYL2, PTPR2, LAMP1, TPBG, and FOLH1 were also up-regulated in asymptomatic monkeys and could serve as candidate early disease biomarkers. For example, DPYL2 was ~21-fold higher in asymptomatic group compared to control group. DPYL2 plays important roles in neuronal development, polarity, axon growth and guidance, neuronal growth cone collapse and cell migration. Zahid and co-workers showed that DPYL2 was up-regulated in the substantia nigra and cortex regions of AD patients using phosphoproteome profiling [35]. Furthermore, Castegna and co-workers showed that DPYL2 protein oxidation was significantly increased in AD brain, which suggests impaired neural network formation [49] and its potential mediation of neurodegeneration in an animal model of multiple sclerosis [50]. This protein might also be involved in the loss of spines seen on striatal neurons in PD and our MPTP monkey model [51]. Another protein that was up-regulated in asymptomatic monkeys is GCPII. GCPII (glutamate carboxypeptidase) is a transmembrane metallopeptidase found mainly in the brain, small intestine, and prostate, and it may convert the abundant neuropeptide, N-acetylaspartylglutamate, to glutamate. Glutamate excitotoxicity has been implicated as a mechanism of motor neuron degeneration in both amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and familial ALS, and this might explain the role of GCPII inhibitors in preventing motor neuron cell death in both systems [52].

The proteins SIRB1, HYOU1, ITAV, SEM4D, and MDHM were progressively increased in MPTP-treated groups or increased in the later stage (symptomatic) only, suggesting their potential usage for disease staging and monitoring disease progression. The signal regulatory protein beta-1 (SIRPB1) is a DAP12-associated transmembrane receptor expressed in a subset of hematopoietic cells. Activation of SIRPB1 increased phagocytosis of microsphere beads, neural debris, and fibrillary amyloid beta and is identified as a novel IFN-induced microglial receptor that supports clearance of neural debris and amyloid beta aggregates by stimulating phagocytosis [53]. SIRPB1 is up-regulated and acted as a phagocytic receptor on microglia in amyloid precursor protein J20 (APP/J20) transgenic mice and in AD patients [53].

Phosphorylation is another important post-translational modification of proteins and plays an integral role in cellular processes including proliferation, cell differentiation, cell death, protein localization, degradation, and complex formation. Accumulating evidence shows that aberrant protein phosphorylation leads to cellular dysfunction, ultimately leading to diseases; and phosphorylated proteins appear to play a prominent role in the formation of pathologic inclusions in both PD and AD [54]. We have identified several phosphoproteins that were differentially expressed in asymptomatic compared to symptomatic monkeys such as G7N8T0 (MTAP2_HUMAN), G7NQJ4 (ALDOA_HUMAN), F7FKM0 (AKA12_HUMAN), G7NB43 (BIN1_HUMAN), F7FEE8 (NEUM_HUMAN), G7ME67 (PEA15_HUMAN), and F7FW77 (ZFY19_HUMAN). Aberrant phosphorylation of MTAP2 proteins leads to their dissociation from microtubules and the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, a hallmark of neurodegeneration. Although the exact function of MTAP2 is unknown, MTAPs may stabilize the microtubules against depolymerization [55–57].

Although some of the candidate biomarkers identified here have already been linked to neurodegeneration in humans, rigorous qualification and validation of these proteins in disease and healthy human subjects are needed to assess the utility and usefulness of these potential biomarkers in clinical settings. Some glycoproteins identified in this study, including PGCB, NCAN, PTPR2, and SEM4D, have been identified in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using complementary approaches including lectin affinity purification and hydrazide chemistry [58]. Additionally, we have initiated evaluations of the diagnostic utility of the altered proteins identified in this study in human CSF and plasma samples in our related projects. For example, HYOU, LSAMP, N1CAM, and SEMA4D have been identified and validated in the plasma of PD patients using glycopeptide enrichment and selected reaction monitoring MS assay [59]. In addition, LRP1 when combined with a 5-peptide model has been found to perform well in differentiating patients with PD and healthy controls [60].

In addition to this unique proteomic investigation in non-human primates, several recent proteomic profiling studies investigated brain protein changes in MPTP mouse models [15–21]. For example, Chin et al [16] identified 86 proteins in mouse striatum with significant abundance changes following neurotoxin treatment that are related to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. A more recent MPTP mouse study observed a total of 518 proteins with substantial abundance changes across different brain regions [20]. Remarkably, in the current study, we observed similar affected categories of biological functions - specifically stress response, cell death, and energy metabolism. Some proteins identified in these previous mouse studies, such as the oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein precursor (OMGp) [16], astrocytic phosphoprotein (PEA15) [20], cytochrome c oxidase (COX) subunits [17, 20] and glutathione S-transferase Mu (GSTM) [15, 16, 20], also displayed significant changes in our monkey study, particularly in the symptomatic group. The other changed proteins uniquely identified in our study could be specific to the monkey model; but as indicated earlier, some of these proteins have already been observed in human CSF or plasma with unique alterations in PD patients, arguing for the advantage of this slow progressive PD model. The other advantage of the current investigation is that we focused on glycoproteins and phosphoproteins that are altered during the early stages in the MPTP-induced neurodegeneration and those proteins might be better biomarker candidates. That said, there exists a limitation in our study that less than optimal protein annotation was observed due to the uncharacterized nature of the rhesus monkey proteome (database) compared to the human and rodent ones. Another limitation of the current study is that for ease of analysis, only the N-linked glycopeptides were analyzed by using a well-established and commonly employed protocol. Although N-linked glycosylation is particularly prevalent in proteins destined for the extracellular environment, i.e., more likely to be biomarker candidates, O-linked glycoproteins/peptides need to be further investigated (e.g., using proper specific cleavage methods) in future studies.

To summarize, this work represents the most comprehensive quantitative proteomic study of the MPTP monkey model of PD. We have identified striatal proteins, particularly glycoproteins and phosphoproteins, which may alter in abundance during early disease stages, even prior to motor symptoms. Our data also indicates that the altered proteins are heavily involved in cellular energy production, protection from oxidative damage, improper protein clearance, transport, and maintenance of synapse integrity. This study has provided potential biomarkers that are currently being further investigated, validated, and translated for their usefulness in early PD diagnosis in human subjects and may also shed insights into understanding the mechanisms underlying the progression from early PD to later stages.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Proteomic profiling in a chronic MPTP-induced non-human primate model of parkinsonism

Complementary quantitative iTRAQ-based, glyco- and phosphoproteomics approaches

Monkey states were verified by neuroimaging and postmortem immunohistological measurements

>300 differentially expressed proteins IDed in asymptomatic and symptomatic monkeys

Several identified proteins were translated for their usefulness in human PD diagnosis

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by generous grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 NS057567, U01 NS082137, P50 NS062684-6221, P30 ES007033-6364, R01 AG033398, R01 ES016873, and R01 ES019277 to JZ). It was also supported in part by the University of Washington’s Proteomics Resource (UWPR95794), a NIH infrastructure grant to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (P51 OD011132), the Emory UDALL Center of Excellence for Parkinson’s Disease (P50 NS071669), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) projects (31200105 and 31470238).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH and other sponsors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lang AE, Lozano AM. Parkinson’s disease. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1044–1053. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connolly BS, Lang AE. Pharmacological treatment of Parkinson disease: a review. JAMA. 2014;311:1670–1683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Abbott RD, Nelson J, Markesbery W, Davis D, Hardman J, Launer L, Masaki K, Tanner CM, White LR. Parkinsonian signs and substantia nigra neuron density in decendents elders without PD. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:532–539. doi: 10.1002/ana.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siderowf A, Lang AE. Premotor Parkinson’s disease: concepts and definitions. Mov Disord. 2012;27:608–616. doi: 10.1002/mds.24954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan JC, Mehta SH, Sethi KD. Biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:423–430. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schapira AH. Recent developments in biomarkers in Parkinson disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2013;26:395–400. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283633741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aasly JO, Shi M, Sossi V, Stewart T, Johansen KK, Wszolek ZK, Uitti RJ, Hasegawa K, Yokoyama T, Zabetian CP, Kim HM, Leverenz JB, Ginghina C, Armaly J, Edwards KL, Snapinn KW, Stoessl AJ, Zhang J. Cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta and tau in LRRK2 mutation carriers. Neurology. 2012;78:55–61. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823ed101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi M, Furay AR, Sossi V, Aasly JO, Armaly J, Wang Y, Wszolek ZK, Uitti RJ, Hasegawa K, Yokoyama T, Zabetian CP, Leverenz JB, Stoessl AJ, Zhang J. DJ-1 and alphaSYN in LRRK2 CSF do not correlate with striatal dopaminergic function. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:836 e835–837. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caudle WM, Bammler TK, Lin Y, Pan S, Zhang J. Using ‘omics’ to define pathogenesis and biomarkers of Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:925–942. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botta-Orfila T, Morato X, Compta Y, Lozano JJ, Falgas N, Valldeoriola F, Pont-Sunyer C, Vilas D, Mengual L, Fernandez M, Molinuevo JL, Antonell A, Marti MJ, Fernandez-Santiago R, Ezquerra M. Identification of blood serum micro-RNAs associated with idiopathic and LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2014;92:1071–1077. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masilamoni G, Votaw J, Howell L, Villalba RM, Goodman M, Voll RJ, Stehouwer J, Wichmann T, Smith Y. (18)F-FECNT: validation as PET dopamine transporter ligand in parkinsonism. Exp Neurol. 2010;226:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masilamoni GJ, Bogenpohl JW, Alagille D, Delevich K, Tamagnan G, Votaw JR, Wichmann T, Smith Y. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 antagonist protects dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons from degeneration in MPTP-treated monkeys. Brain. 2011;134:2057–2073. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blesa J, Pifl C, Sanchez-Gonzalez MA, Juri C, Garcia-Cabezas MA, Adanez R, Iglesias E, Collantes M, Penuelas I, Sanchez-Hernandez JJ, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Avendano C, Hornykiewicz O, Cavada C, Obeso JA. The nigrostriatal system in the presymptomatic and symptomatic stages in the MPTP monkey model: a PET, histological and biochemical study. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;48:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao X, Li Q, Zhao L, Pu X. Proteome analysis of substantia nigra and striatal tissue in the mouse MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1:1559–1569. doi: 10.1002/prca.200700077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin MH, Qian WJ, Wang H, Petyuk VA, Bloom JS, Sforza DM, Lacan G, Liu D, Khan AH, Cantor RM, Bigelow DJ, Melega WP, Camp DG, 2nd, Smith RD, Smith DJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and apoptosis revealed by proteomic and transcriptomic analyses of the striata in two mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:666–677. doi: 10.1021/pr070546l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diedrich M, Mao L, Bernreuther C, Zabel C, Nebrich G, Kleene R, Klose J. Proteome analysis of ventral midbrain in MPTP-treated normal and L1cam transgenic mice. Proteomics. 2008;8:1266–1275. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu B, Shi Q, Ma S, Feng N, Li J, Wang L, Wang X. Striatal 19S Rpt6 deficit is related to alpha-synuclein accumulation in MPTP-treated mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jeon S, Kim YJ, Kim ST, Moon W, Chae Y, Kang M, Chung MY, Lee H, Hong MS, Chung JH, Joh TH, Lee H, Park HJ. Proteomic analysis of the neuroprotective mechanisms of acupuncture treatment in a Parkinson’s disease mouse model. Proteomics. 2008;8:4822–4832. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Zhou JY, Chin MH, Schepmoes AA, Petyuk VA, Weitz KK, Petritis BO, Monroe ME, Camp DG, Wood SA, Melega WP, Bigelow DJ, Smith DJ, Qian WJ, Smith RD. Region-specific protein abundance changes in the brain of MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mouse model. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1496–1509. doi: 10.1021/pr901024z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim ST, Moon W, Chae Y, Kim YJ, Lee H, Park HJ. The effect of electroaucpuncture for 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced proteomic changes in the mouse striatum. J Physiol Sci. 2010;60:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s12576-009-0061-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadipour-Niktarash A, Rommelfanger KS, Masilamoni GJ, Smith Y, Wichmann T. Extrastriatal D2-like receptors modulate basal ganglia pathways in normal and Parkinsonian monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:1500–1512. doi: 10.1152/jn.00348.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi M, Hwang H, Zhang J. Quantitative characterization of glycoproteins in neurodegenerative disorders using iTRAQ. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;951:279–296. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-146-2_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang HJ, Quinn T, Zhang J. Identification of glycoproteins in human cerebrospinal fluid. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;566:263–276. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-562-6_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazanek M, Mituloviae G, Herzog F, Stingl C, Hutchins JR, Peters JM, Mechtler K. Titanium dioxide as a chemo-affinity solid phase in offline phosphopeptide chromatography prior to HPLC-MS/MS analysis. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1059–1069. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdi F, Quinn JF, Jankovic J, McIntosh M, Leverenz JB, Peskind E, Nixon R, Nutt J, Chung K, Zabetian C, Samii A, Lin M, Hattan S, Pan C, Wang Y, Jin J, Zhu D, Li GJ, Liu Y, Waichunas D, Montine TJ, Zhang J. Detection of biomarkers with a multiplex quantitative proteomic platform in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurodegenerative disorders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:293–348. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarthy FM, Bridges SM, Wang N, Magee GB, Williams WP, Luthe DS, Burgess SC. AgBase: a unified resource for functional analysis in agriculture. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D599–603. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Li XJ, Martin DB, Aebersold R. Identification and quantification of N-linked glycoproteins using hydrazide chemistry, stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:660–666. doi: 10.1038/nbt827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y, Zhang S, Howe K, Wilson DB, Moser F, Irwin D, Thannhauser TW. A comparison of nLC-ESI-MS/MS and nLC-MALDI-MS/MS for GeLC-based protein identification and iTRAQ-based shotgun quantitative proteomics. J Biomol Tech. 2007;18:226–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheri RC, Lee J, Curtis LR, Barofsky DF. A comparison of relative quantification with isobaric tags on a subset of the murine hepatic proteome using electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization tandem time-of-flight. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:3137–3146. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shirran SL, Botting CH. A comparison of the accuracy of iTRAQ quantification by nLC-ESI MSMS and nLC-MALDI MSMS methods. J Proteomics. 2010;73:1391–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez A, Dalfo E, Muntane G, Ferrer I. Glycolitic enzymes are targets of oxidation in aged human frontal cortex and oxidative damage of these proteins is increased in progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:59–66. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0800-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Licker V, Cote M, Lobrinus JA, Rodrigo N, Kovari E, Hochstrasser DF, Turck N, Sanchez JC, Burkhard PR. Proteomic profiling of the substantia nigra demonstrates CNDP2 overexpression in Parkinson’s disease. J Proteomics. 2012;75:4656–4667. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wildsmith KR, Schauer SP, Smith AM, Arnott D, Zhu Y, Haznedar J, Kaur S, Mathews WR, Honigberg LA. Identification of longitudinally dynamic biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid by targeted proteomics. Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zahid S, Oellerich M, Asif AR, Ahmed N. Phosphoproteome profiling of substantia nigra and cortex regions of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Neurochem. 2012;121:954–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Itoh T, De Camilli P. BAR, F-BAR (EFC) and ENTH/ANTH domains in the regulation of membrane-cytosol interfaces and membrane curvature. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761:897–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burns RS, Chiueh CC, Markey SP, Ebert MH, Jacobowitz DM, Kopin IJ. A primate model of parkinsonism: selective destruction of dopaminergic neurons in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra by N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4546–4550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Paolo T, Bedard P, Daigle M, Boucher R. Long-term effects of MPTP on central and peripheral catecholamine and indoleamine concentrations in monkeys. Brain Res. 1986;379:286–293. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science. 1983;219:979–980. doi: 10.1126/science.6823561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elsworth JD, Deutch AY, Redmond DE, Jr, Taylor JR, Sladek JR, Jr, Roth RH. Symptomatic and asymptomatic 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-treated primates: biochemical changes in striatal regions. Neuroscience. 1989;33:323–331. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villalba RM, Wichmann T, Smith Y. Neuronal loss in the caudal intralaminar thalamic nuclei in a primate model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219:381–394. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0507-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Link AJ, Eng J, Schieltz DM, Carmack E, Mize GJ, Morris DR, Garvik BM, Yates JR., 3rd Direct analysis of protein complexes using mass spectrometry. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:676–682. doi: 10.1038/10890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S, Purkayastha S, Juhasz P, Martin S, Bartlet-Jones M, He F, Jacobson A, Pappin DJ. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:1154–1169. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400129-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hwang H, Zhang J, Chung KA, Leverenz JB, Zabetian CP, Peskind ER, Jankovic J, Su Z, Hancock AM, Pan C, Montine TJ, Pan S, Nutt J, Albin R, Gearing M, Beyer RP, Shi M, Zhang J. Glycoproteomics in neurodegenerative diseases. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2010;29:79–125. doi: 10.1002/mas.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang J, Goodlett DR, Montine TJ. Proteomic biomarker discovery in cerebrospinal fluid for neurodegenerative diseases. J Alzheimers Dis. 2005;8:377–386. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi M, Bradner J, Bammler TK, Eaton DL, Zhang J, Ye Z, Wilson AM, Montine TJ, Pan C, Zhang J. Identification of glutathione S-transferase pi as a protein involved in Parkinson disease progression. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:54–65. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi M, Caudle WM, Zhang J. Biomarker discovery in neurodegenerative diseases: a proteomic approach. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;35:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi M, Jin J, Wang Y, Beyer RP, Kitsou E, Albin RL, Gearing M, Pan C, Zhang J. Mortalin: a protein associated with progression of Parkinson disease? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:117–124. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e318163354a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castegna A, Aksenov M, Aksenova M, Thongboonkerd V, Klein JB, Pierce WM, Booze R, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Proteomic identification of oxidatively modified proteins in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Part I: creatine kinase BB, glutamine synthase, and ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L-1. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:562–571. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00914-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jastorff AM, Haegler K, Maccarrone G, Holsboer F, Weber F, Ziemssen T, Turck CW. Regulation of proteins mediating neurodegeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2009;3:1273–1287. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villalba RM, Lee H, Smith Y. Dopaminergic denervation and spine loss in the striatum of MPTP-treated monkeys. Exp Neurol. 2009;215:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghadge GD, Slusher BS, Bodner A, Canto MD, Wozniak K, Thomas AG, Rojas C, Tsukamoto T, Majer P, Miller RJ, Monti AL, Roos RP. Glutamate carboxypeptidase II inhibition protects motor neurons from death in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9554–9559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530168100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaikwad S, Larionov S, Wang Y, Dannenberg H, Matozaki T, Monsonego A, Thal DR, Neumann H. Signal regulatory protein-beta1: a microglial modulator of phagocytosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2528–2539. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caudle WM, Pan S, Shi M, Quinn T, Hoekstra J, Beyer RP, Montine TJ, Zhang J. Proteomic identification of proteins in the human brain: Towards a more comprehensive understanding of neurodegenerative disease. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2008;2:1484–1497. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rizzu P, Van Swieten JC, Joosse M, Hasegawa M, Stevens M, Tibben A, Niermeijer MF, Hillebrand M, Ravid R, Oostra BA, Goedert M, van Duijn CM, Heutink P. High prevalence of mutations in the microtubule-associated protein tau in a population study of frontotemporal dementia in the Netherlands. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:414–421. doi: 10.1086/302256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sanchez C, Diaz-Nido J, Avila J. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) and its relevance for the regulation of the neuronal cytoskeleton function. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:133–168. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanchez C, Perez M, Avila J. GSK3beta-mediated phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein 2C (MAP2C) prevents microtubule bundling. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:252–260. doi: 10.1078/s0171-9335(04)70028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pan S, Wang Y, Quinn JF, Peskind ER, Waichunas D, Wimberger JT, Jin J, Li JG, Zhu D, Pan C, Zhang J. Identification of glycoproteins in human cerebrospinal fluid with a complementary proteomic approach. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2769–2779. doi: 10.1021/pr060251s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pan C, Zhou Y, Dator R, Ginghina C, Zhao Y, Movius J, Peskind E, Zabetian CP, Quinn J, Galasko D, Stewart T, Shi M, Zhang J. Targeted Discovery and Validation of Plasma Biomarkers of Parkinson’s Disease. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:4535–4545. doi: 10.1021/pr500421v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi M, Movius J, Dator R, Aro P, Zhao Y, Pan C, Lin X, Bammler TK, Stewart T, Zabetian CP, Peskind ER, Hu S, Quinn JF, Galasko DR, Zhang J. Cerebrospinal fluid peptides as potential Parkinson disease biomarkers: a staged pipeline for discovery and validation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:544–555. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.040576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.