Significance

Macrophages maintain homeostatic proliferation in the presence of mitogens whereas encounters with invading microorganisms inhibit proliferation and engage a rapid proinflammatory response. Such cell fate change requires an extensive reprogramming of metabolism, and the regulatory mechanisms behind this change remain unknown. We found that myelocytomatosis viral oncogen (Myc) plays a major role in regulating proliferation-associated metabolic programs. However, proinflammatory stimuli suppress Myc and cell proliferation and engage a hypoxia-inducible factor alpha (HIF1α)-dependent transcriptional program that is responsible for heightened glycolysis. Our work indicates that a switch from a Myc-dependent to a HIF1α-dependent transcriptional program may regulate the robust bioenergetic support for inflammatory response, while sparing Myc-dependent proliferation.

Keywords: metabolism, macrophage, cell cycle, Myc, HIF1α

Abstract

As a phenotypically plastic cellular population, macrophages change their physiology in response to environmental signals. Emerging evidence suggests that macrophages are capable of tightly coordinating their metabolic programs to adjust their immunological and bioenergetic functional properties, as needed. Upon mitogenic stimulation, quiescent macrophages enter the cell cycle, increasing their bioenergetic and biosynthetic activity to meet the demands of cell growth. Proinflammatory stimulation, however, suppresses cell proliferation, while maintaining a heightened metabolic activity imposed by the production of bactericidal factors. Here, we report that the mitogenic stimulus, colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1), engages a myelocytomatosis viral oncogen (Myc)-dependent transcriptional program that is responsible for cell cycle entry and the up-regulation of glucose and glutamine catabolism in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). However, the proinflammatory stimulus, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), suppresses Myc expression and cell proliferation and engages a hypoxia-inducible factor alpha (HIF1α)-dependent transcriptional program that is responsible for heightened glycolysis. The acute deletion of Myc or HIF1α selectively impaired the CSF-1– or LPS-driven metabolic activities in BMDM, respectively. Finally, inhibition of glycolysis by 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) or genetic deletion of HIF1α suppressed LPS-induced inflammation in vivo. Our studies indicate that a switch from a Myc-dependent to a HIF1α-dependent transcriptional program may regulate the robust bioenergetic support for an inflammatory response, while sparing Myc-dependent proliferation.

The cells of the immune system are constantly exposed to environmental challenges and are capable of tailoring their metabolic programs to meet distinct physiological needs. Macrophages, like other immune cells, rapidly change their physiology in response to various environmental cues. Macrophages undergo proliferation in response to mitogenic stimuli, such as colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) [also known as macrophage CSF (M-CSF)], and this cellular turnover is essential for macrophage homeostasis and may occur in mature macrophages, bypassing the need for self-renewing progenitors (1, 2). Proliferating macrophages consume considerable amounts of energy and require de novo synthesis of macromolecules to support their growth and proliferation (3–6). Therefore, macrophages must coordinately regulate metabolic programs to meet their bioenergetic and biosynthetic demand during proliferation. Despite the emerging view that extracellular signaling events dictate cell growth, proliferation, and death, in part by modulating metabolic activities in cancer cells and T lymphocytes, the precise mechanisms and crucial players of reprogramming metabolism during macrophage proliferation are incompletely understood.

Upon encountering an invading microorganism, the bioenergetic potential in macrophages quickly shifts away from fulfilling the needs of cell proliferation to mount a robust response to resolve the immunological insult. The combination of the bacterial component, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and the proinflammatory cytokine, IFN-γ, triggers the differentiation of M1 macrophages, in a process often referred to as the classical activation program (7, 8). To mount a rapid and effective immune response against highly proliferative intracellular pathogens, M1 macrophages produce nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12. This process is rapid and energy-intensive and therefore requires a reconfiguration of metabolic programs that may provide the host with a competitive bioenergetic advantage against pathogens. Earlier studies suggest that macrophages exit from the cell cycle during M1 differentiation, indicating a potential coordination between metabolic regulation and macrophage physiology (9–15).

M1 macrophage differentiation via proinflammatory stimulation induces the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), resulting in an iNOS-mediated breakdown of arginine to produce NO and promote glucose catabolic routes, largely through aerobic glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (12, 16, 17). Heightened glycolysis is required for ATP generation in M1 macrophages and also provides precursors for lipid and amino acid biosynthesis, all of which may support intracellular membrane reorganization and the production and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (17–20). Meanwhile, the increase of PPP-derived NADPH supports the production of reduced glutathione and therefore limits oxidative stress in M1 macrophages (12, 21, 22).

The transcriptional induction of glycolytic enzymes, such as phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK), glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1), and ubiquitous 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (uPFK2), is involved in promoting glycolysis in M1 macrophages (23, 24). Emerging evidence also suggests that the fine-tuning of the activity of Pyruvate Kinase M2 (PKM2) is required for an optimized inflammatory response in various pathological contexts (25, 26). In addition to its role in promoting the transcription of proangiogenic factors and proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages, the transcriptional factor hypoxia-inducible factor alpha (HIF1α) may also regulate the transcription of the above glycolytic enzymes (16, 24, 27). Conversely, a decrease in carbohydrate kinase-like protein (CARKL) is implicated in the shuttling of glucose catabolism to the oxidative arm of the PPP in M1 macrophages (21). Beyond these metabolic regulations, previous studies have identified gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter, in extracts of human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages (28). The related “GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) shunt” pathway provides a source of succinate, the intracellular level of which determines the stability of HIF1α and its proinflammatory activity in M1 macrophage (16).

These findings prompted us to ask how macrophages coordinate their metabolic programs to meet their distinct physiological needs in response to mitogenic signaling versus proinflammatory signaling. Our studies show that CSF-1–driven mitogenic signaling engages the myelocytomatosis viral oncogen (Myc)-dependent transcriptome, promoting cell proliferation and catabolism of glucose and glutamine whereas LPS-driven inflammatory signaling suppresses Myc-dependent proliferation and enhances the HIF1α-dependent transcription of glycolytic enzymes, leading to heightened aerobic glycolysis. This change may allow M1 macrophages to divert bioenergetics and biosynthetic resources away from supporting proliferation, thus optimizing metabolic capacity to fulfill the needs of an inflammatory response. Our results further emphasize the important role of HIF1α-dependent glycolysis in the modulation of M1 macrophage function in vivo by demonstrating that the inhibition of glycolysis by 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) or genetic deletion of HIF1α significantly suppresses inflammation in a murine sepsis model.

Results

Macrophage Metabolic Reprogramming in Response to Proinflammatory and Mitogenic Stimulation.

Like many other immune cells, macrophages can rapidly adjust their metabolic activity in response to various environmental cues. CSF-1 (also known as M-CSF) is the main macrophage mitogen, driving the survival, proliferation, and maturation of macrophages. A combination of microbial components, such as LPS plus IFN-γ, however, can result in classically activated macrophages (also known as M1 macrophages) that exert rapid and effective proinflammatory and microbicidal responses. To understand how macrophages adapt their metabolic programs to meet the bioenergetic demand from mitogenic stimuli or to mediate the immune effector function required by immunological insult, we deprived bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) of CSF-1 for 24 h and then either restimulated BMDMs with CSF-1 or stimulated BMDMs with LPS and IFN-γ (M1 induction) for 24 h.

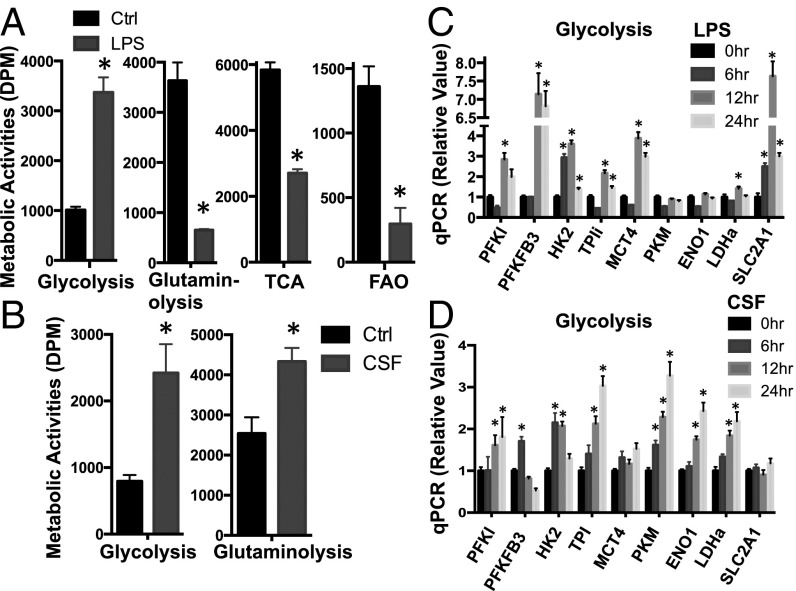

After the above treatments, we used radiochemical-based approaches to follow the metabolic activities in these cells. Consistent with early studies (12, 17–20, 23, 29), M1 macrophages significantly up-regulated glycolysis in a time-dependent manner, indicated by the detritiation of [3-3H]-glucose (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A). In contrast, mitochondria-dependent pyruvate oxidation through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, indicated by 14CO2 release from [2-14C]-pyruvate; mitochondria-dependent fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO), indicated by the detritiation of [9,10-3H]-palmitic acid; and glutamine consumption through oxidative catabolism, indicated by 14CO2 release from [U-14C]-glutamine, were markedly down-regulated upon LPS and IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. 1A). Consistent with these results, oxygen consumption was also significantly dampened in M1 macrophages (Fig. S1B). In CSF-1–treated macrophages, however, we observed a significant up-regulation of both glycolysis and glutamine oxidative catabolism (Fig. 1B). Taken together, our metabolic and transcriptional profiling demonstrates that mitogenic stimulation with CSF-1 or proinflammatory stimulation with LPS plus IFN-γ differentially enhances or suppresses glutamine catabolism. However, both conditions promote glycolysis.

Fig. 1.

Proinflammatory and mitogenic stimulation differentially drives macrophage metabolic reprogramming. (A and B) Untreated BMDMs (Ctrl) and LPS-stimulated (A) or CSF-stimulated BMDMs (B) were collected at 24 h after stimulation and were used for measuring the generation of 3H2O from [3-3H]-glucose (glycolysis) or from [9,10-3H]-palmitic acid (fatty acid beta-oxidation) and from [U-14C]-glutamine (glutaminolysis) or from [2-14C]-pyruvate (TCA). (C and D) RNAs were isolated from BMDMs collected at the indicated time after LPS (C) or CSF (D) stimulation and used for real-time PCR analyses of metabolic genes in the glycolytic pathway and in the glutaminolytic pathway. The relative gene expression was determined by the comparative CT method, also referred to as the 2−ΔΔCT method. Error bars represent SD from the mean of triplicate qPCR reactions. Data are representative of three independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. An equal number of cells were used in the radioisotopic experiments. DPM, disintegrations per min.

Fig. S1.

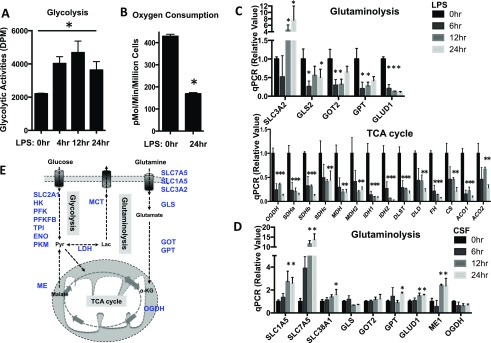

Proinflammatory and mitogenic stimulation differentially drives macrophage metabolic reprogramming. (A and B) BMDMs collected at the indicated time after LPS stimulation were used for measure glycolysis (A) and oxygen consumption (B) by the Seahorse XF24 analyzer. Error bars represent SD from the mean of triplicate samples. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (C and D) RNAs were isolated from BMDMs collected at the indicated time after LPS (C) or CSF (D) stimulation and used for real-time PCR analyses of metabolic genes in the indicated pathways. The relative gene expression was determined as described in detail in Fig. 1. Error bars represent SD from the mean of triplicate qPCR reactions. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (E) Diagram of cell metabolic pathways, with key metabolic genes highlighted in blue (examined by qPCR in Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). Of note, α-KG represents alpha-ketoglutarate. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. An equal number of cells were used in the radioisotopic experiments.

Macrophage Metabolic Reprogramming Is Associated with Changes in the Metabolic Gene Transcriptome.

Mitogenic and proinflammatory stimulation drives distinct transcriptional programs, including cell cycle and inflammation, respectively. We therefore hypothesized that induction of the metabolic gene transcriptome in macrophages is associated with metabolic rewiring upon CSF-1 or LPS plus IFN-γ stimulation. We focused on the metabolic pathways that are up-regulated upon stimulation and measured the mRNA levels of metabolic genes involved. Consistent with the results from our metabolic assays (Fig. 1A), the expression of mRNAs encoding glycolytic enzymes and transporters was induced, but the expression of mRNAs encoding essential metabolic enzymes in glutamine catabolism and the TCA cycle was suppressed after LPS plus IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1 C and D). Similarly, the expression of mRNAs encoding glycolytic enzymes and transporters and the expression of mRNAs encoding essential metabolic enzymes in glutamine catabolism were induced upon CSF-1 stimulation (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1E). Taken together, these results are consistent with our metabolic activity data and indicate that the regulation of metabolic gene transcription is associated with macrophage metabolic rewiring upon mitogenic or proinflammatory stimulation.

CSF-1 Stimulation Drives a Myc-Dependent Metabolic Rewiring in Macrophages.

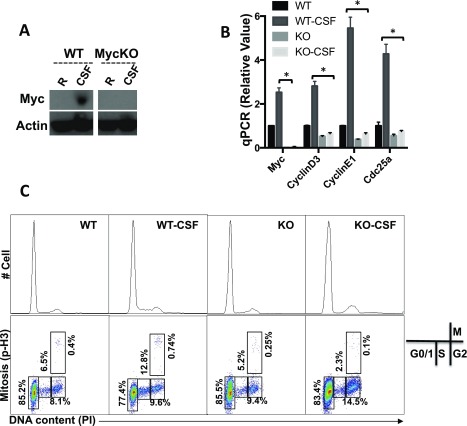

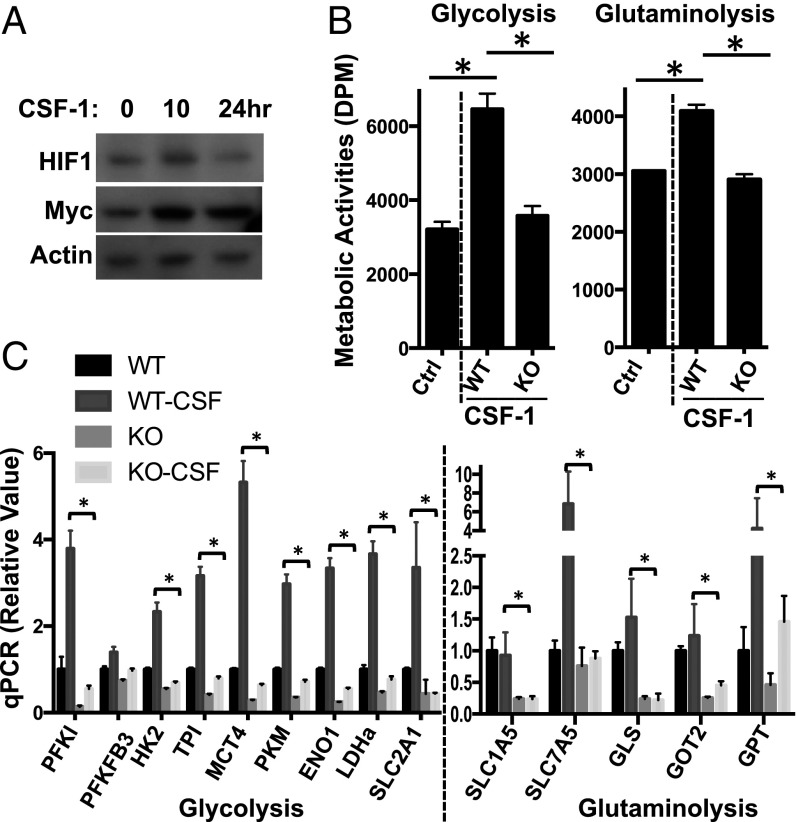

We next explored the molecular mechanisms behind the regulation of metabolic gene transcription and metabolic rewiring upon CSF-1 stimulation in macrophages. Previous studies have revealed that transcription factors HIF1α and myelocytomatosis oncogene (Myc) are involved in regulating glycolysis and glutaminolysis, respectively, in both cancer cells and immune cells (30–36). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis revealed that the mRNA of Myc was significantly up-regulated in macrophages upon CSF-1 stimulation (Fig. S2B). Western blot analysis further confirmed the up-regulation of Myc at the protein level (Fig. 2A). The protein level of HIF1α remained unchanged in macrophages upon CSF-1 stimulation (Fig. 2A).

Fig. S2.

Myc is required for CSF-driven proliferation and metabolic reprogramming in macrophage. BMDMs generated from either RosaCreERTam−, Mycflox/flox mice (WT) or RosaCreERTam+, Mycflox/flox mice (KO) were pretreated with 500 nM 4OHT (+4OHT). Untreated BMDMs (Ctrl) or CSF-stimulated BMDM (CSF) were collected 24 h after stimulation. The protein level of c-Myc (A) and mRNA level of the indicated genes (B) were determined by Western blot and qPCR, respectively. Of note, the blots of Myc and Actin were from two gels, both of which were from the same batch of samples. The relative gene expression was determined as described in detail in Fig. 1. Error bars represent SD from the mean of triplicate qPCR reactions. Data are representative of two independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. (C) The indicated BMDM groups were CSF-1 starved for 2 d before CSF-1 stimulation. The cell cycle profile was determined as the combinational staining of propidium iodide (PI) and p-Histone H3 antibody (p-H3) by flow cytometry.

Fig. 2.

Myc is required for CSF-driven proliferation and metabolic reprogramming in macrophage. (A) The protein levels of HIF1α and c-Myc in BMDMs collected at the indicated time after CSF stimulation were determined by Western blot. (B and C) BMDMs generated from either RosaCreERTam−, Mycflox/flox mice (WT) or RosaCreERTam+, Mycflox/flox mice (KO) were pretreated with 500 nM 4OHT (+4OHT). Untreated BMDMs (Ctrl) or CSF-stimulated BMDM (CSF) were used for measuring indicated metabolic activities (B) or the mRNA expression of indicated metabolic gene expression (C). The relative gene expression was determined as described in detail in Fig. 1. Error bars represent SD from the mean of triplicate qPCR reactions. Data are representative of two independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. An equal number of cells were used in the radioisotopic experiments.

We next asked whether the up-regulation of Myc is required for CSF-1–driven metabolic rewiring in macrophages. Previously, we established a mouse model (Mycflox/flox, CreERTam), where a tamoxifen-induced Cre recombinase deletes Myc floxed alleles in an acute manner. To obtain an efficient deletion ex vivo, we cultured freshly established BMDMs for 2 d in the absence (WT) or in the presence (KO) of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT). An efficient deletion of Myc was observed at the protein (Fig. S2A) and mRNA (Fig. S2B) levels. After CSF-1 stimulation, the level of Myc, the up-regulation of glycolysis, glutaminolysis, and the expression of metabolic genes involved were significantly dampened in Myc KO macrophages upon CSF-1 stimulation (Fig. 2 B and C). Together, these results suggest that the acute deletion of Myc impairs CSF-1–induced metabolic rewiring in macrophages.

Myc Is Required for CSF-1–Driven Macrophage Proliferation.

Previous studies have suggested an essential role for Myc in the CSF-1–induced mitogenic response in macrophages (37). Thus, we tested the requirement of Myc in macrophage proliferation. We cultured BMDMs established from Mycflox/flox, CreERTam mice for 2 d in the absence (WT) or in the presence (KO) of 4OHT, during which CSF-1 was also withdrawn from culture media. After CSF-1 re-addition, the cell cycle profile was determined by FACS analysis of the DNA content and mitotic index. We found that CSF-1 stimulation increased the percentage of macrophages in S-phase and in mitosis and that acute deletion of Myc abolished these changes (Fig. S2C). Previous studies have revealed that G1-S phase regulators, cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), cyclin D3, and CDC25a, are downstream targets of Myc in transformed cells. To determine whether these cell cycle regulators are also under the control of Myc in macrophages, we examined the mRNA expression of these genes by qPCR and found that all three genes were up-regulated in a Myc-dependent manner upon CSF-1 stimulation (Fig. S2B). Together, these results suggest that the acute deletion of Myc impairs CSF-1–driven proliferation in macrophages.

Proinflammatory Stimulation with LPS and IFN-γ Suppresses Myc Expression and Proliferation in Macrophages.

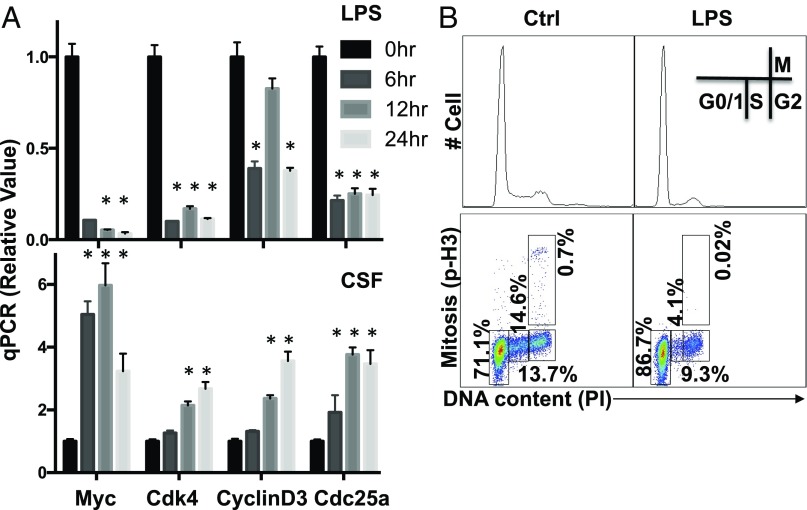

We next determined the impact of proinflammatory stimulation on Myc expression in macrophages. We first examined the expression of the Myc gene by qPCR upon CSF-1 stimulation or LPS plus IFN-γ stimulation. Although CSF-1 induced Myc mRNA expression, LPS plus IFN-γ dramatically suppressed Myc mRNA expression (Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis further confirmed the down-regulation of Myc at the protein level (Fig. S3B). Consistent with these changes in Myc expression, the mRNA expression of cell cycle regulators CDK4, cyclin D3, and CDC25a was up-regulated in a time-dependent manner upon CSF-1 stimulation, yet was down-regulated in macrophages upon LPS plus IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis confirmed the down-regulation of CDK4, cyclin D3, and CDC25a at the protein level (Fig. S3B). To further determine the impact of proinflammatory stimulation on cell proliferation, we analyzed the cell cycle profile by FACS. Upon LPS plus IFN-γ stimulation, the percentage of macrophages in S-phage and mitosis was significantly reduced (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Metabolic rewiring during macrophage M1 polarization is associated with cell cycle blockage. (A) BMDMs cultured in differentiation medium (with the presence of CSF-1) collected at the indicated time after LPS stimulation (Upper) and CSF stimulation (Lower) were used to determine the mRNA level of indicated genes by qPCR. The relative gene expression was determined as described in detail in Fig. 1. Error bars represent SD from the mean of triplicate qPCR reactions. Data are representative of two independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. (B) Untreated BMDMs (Ctrl) and LPS-stimulated (LPS) were collected at 24 h after stimulation. The cell cycle profile in indicated groups was determined as the combinational staining of propidium iodide (PI) and p-Histone H3 antibody (p-H3) by flow cytometry.

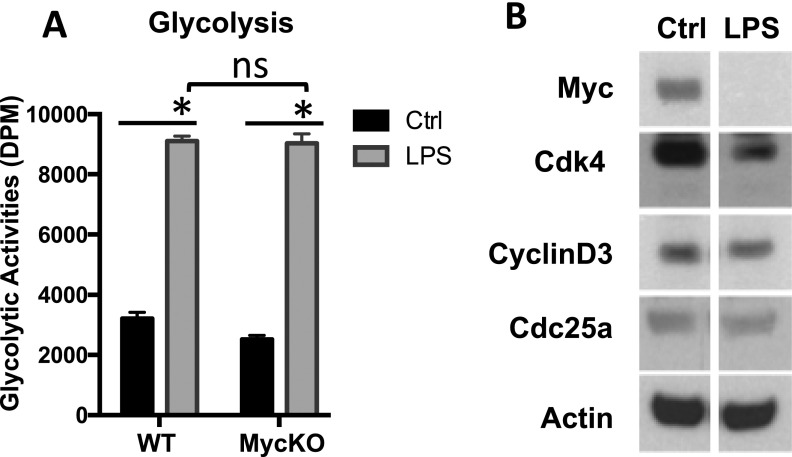

Fig. S3.

Metabolic rewiring during macrophage M1 polarization is associated with cell cycle blockage. (A) BMDMs generated from either RosaCreERTam−, Mycflox/flox mice (WT) or RosaCreERTam+, Mycflox/flox mice (KO) were pretreated with 500 nM 4OHT (+4OHT). Untreated BMDMs (Ctrl) or LPS-stimulated BMDMs (LPS) were collected 24 h after stimulation and were used to determine glycolysis rate. An equal number of cells were used in the radioisotopic experiments. (B) Untreated BMDMs (Ctrl) and LPS-stimulated (LPS) were collected at 24 h after stimulation. The protein levels of the indicated genes were determined by Western blot. Of note, these blots were from two transferred membranes but from the same batch of samples (lysates). Each membrane was cut into two parts (on the 50-kDa marker), which were probed for targets based on their estimated molecular weights. The actin result was a representative result from reprobing of the stripped blot.

Stimulation with LPS plus IFN-γ up-regulates glycolysis and induces the expression of glycolytic genes in macrophages (Fig. 1 A and C). The down-regulation of Myc upon proinflammatory stimulation suggests that Myc is not required for the increase in glycolysis and the induction of glycolytic genes. Our metabolic activity analysis further validated our hypothesis by showing that acute deletion of Myc did not impair the up-regulation of glycolysis upon LPS plus IFN-γ stimulation (Fig. S3A). Together, these results demonstrate that proinflammatory stimulation suppresses Myc expression and proliferation in macrophages.

HIF1α Is Required for Proinflammatory Stimulation-Driven Metabolic Rewiring in Macrophages.

Having excluded the requirement for Myc in regulating glycolysis in macrophages upon proinflammatory stimulation, we tested the requirement for HIF1α. Previous studies have implicated HIF1α as an essential transcriptional factor that regulates myeloid cell and lymphocyte development and inflammatory function (27, 33–36). HIF1α is required for the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and metabolic genes involved in glycolysis in M1 macrophages (16, 24). Consistent with these studies, qPCR analysis and Western blot analysis revealed an induction of HIF1α upon LPS plus IFN-γ stimulation at the mRNA and protein level, respectively (Fig. S4 A and B).

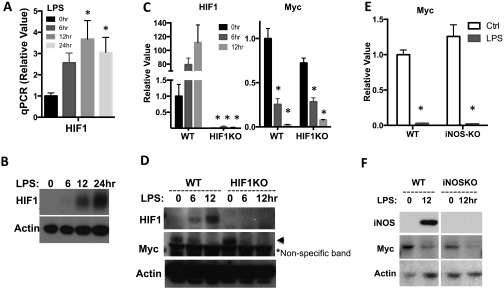

Fig. S4.

Induction of HIF1α mRNA and protein by LPS in macrophage. (A–F) The mRNA (A, C, and E) and protein (B, D, and F) levels of the indicated genes in BMDMs collected at the indicated time after LPS stimulation were determined by qPCR and Western blot, respectively. The relative gene expression was determined as described in detail in Fig. 1. Error bars represent SD from the mean of triplicate qPCR reactions. Data are representative of two independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

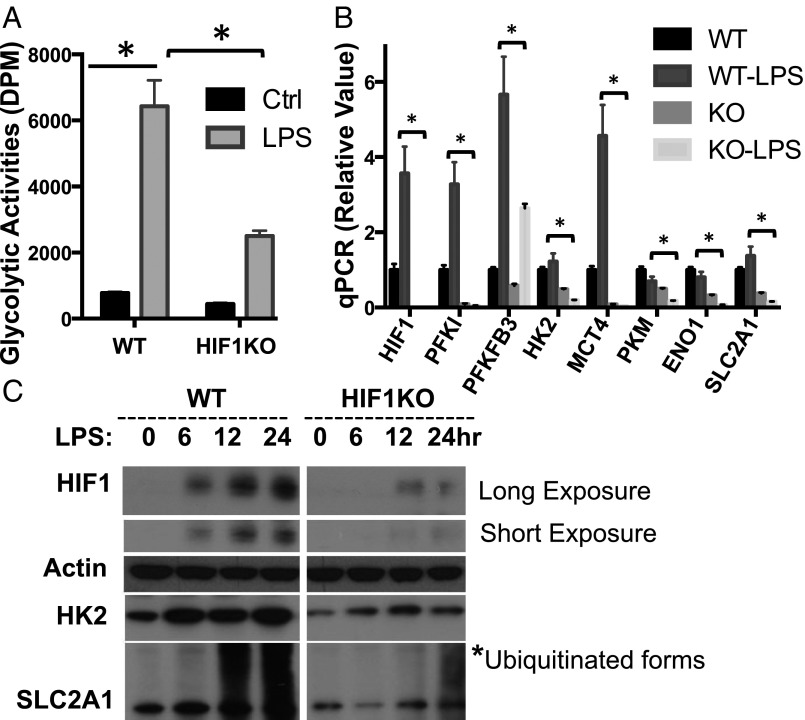

We have previously established a mouse model (HIF1αflox/flox, CreERT2), which allows us to delete HIF1α floxed alleles in an acute manner and therefore avoid any potential developmental defect caused by lineage-specific deletion. To determine the requirement of HIF1α in M1 macrophage glycolysis, we cultured BMDMs for 2 d in the absence (WT) or in the presence (KO) of 4OHT. Following stimulation with LPS plus IFN-γ, the level of HIF1α, glycolytic activity, and the expression of glycolytic genes were examined (Fig. 4). We found that the acute deletion of HIF1α significantly dampened LPS-induced glycolysis and the expression of metabolic genes (Fig. 4). The blunted, but not ablated, glycolysis and the expression of metabolic enzymes is likely due to the presence of residual HIF1α-expressing WT macrophages, as evidenced by HIF1α immunoblot (Fig. 4C). We have shown that LPS stimulation suppresses Myc expression (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3B) and induces glycolysis in the absence of Myc (Fig. S3A). We further examined whether HIF1α is required for suppressing Myc after LPS stimulation. LPS stimulation suppressed Myc expression in both HIF1α WT and KO macrophages (Fig. S4 C and D). Similarly, iNOS, a critical proinflammatory effector in LPS-stimulated macrophages, was not involved in suppressing Myc (Fig. S4 E and F). Together, these results suggest that the acute deletion of HIF1α impairs LPS plus IFN-γ –induced, but not Myc-dependent, metabolic rewiring in macrophages.

Fig. 4.

HIF1α is required for LPS-driven glycolysis in macrophage. (A and B) BMDMs generated from either RosaCreERT2-, HIF1αflox/flox mice (WT) or RosaCreERT2+, HIF1αflox/flox mice (KO) were pretreated with 500 nM 4OHT (+4OHT). Untreated BMDMs (Ctrl) or LPS-stimulated BMDM (LPS) were collected 24 h after stimulation. The rate of glycolysis (A) and the expression of indicated mRNA (B) were determined by radioactive tracer-based assay and qPCR, respectively. The relative gene expression was determined as described in detail in Fig. 1. Error bars represent SD from the mean of triplicate qPCR reactions. Data are representative of two independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. (C) BMDMs in indicated groups were collected at the indicated time after LPS stimulation. The protein levels of indicated genes were determined by Western blot. Of note, these blots were from two transferred membranes but from the same batch of samples (lysates). The actin result was a representative result from reprobing of a stripped blot. An equal number of cells were used in the radioisotopic experiments.

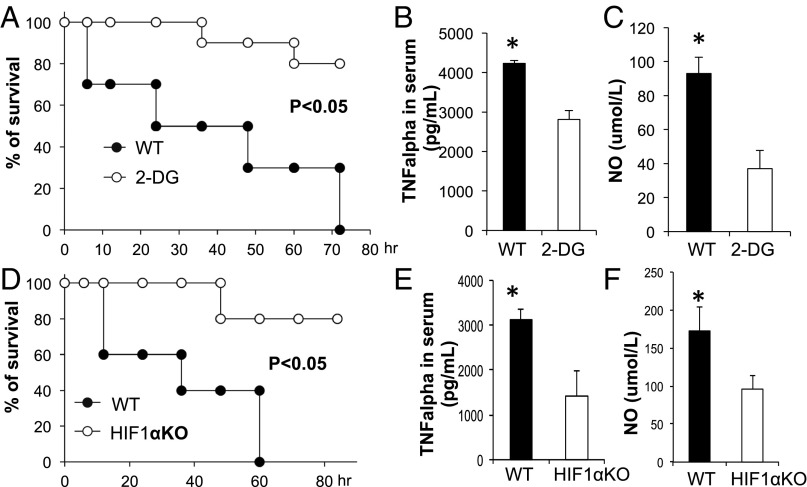

Inhibition of Glycolysis or HIF1α Deletion Dampens Macrophage Proinflammatory Responses in a Murine Sepsis Model.

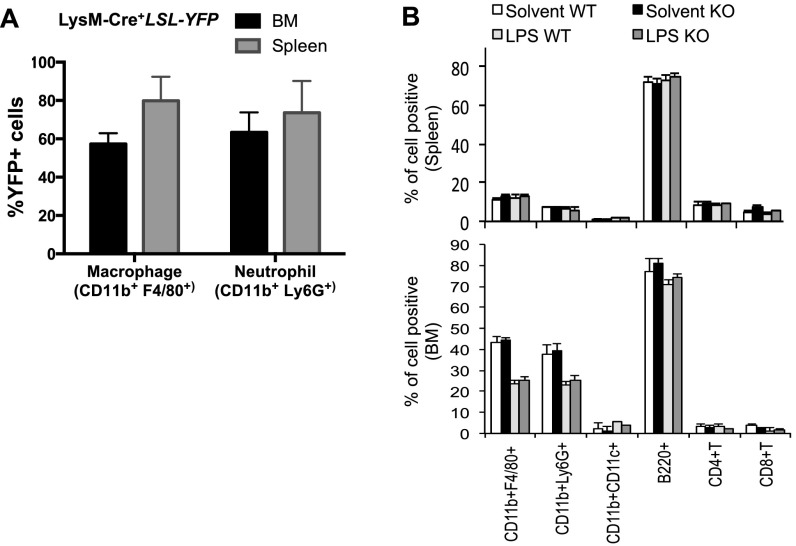

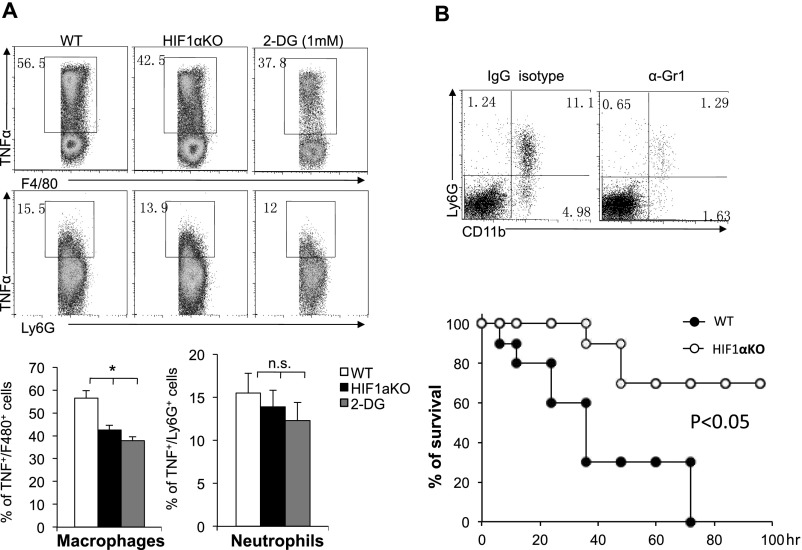

To further our investigation of heightened glycolysis during proinflammatory responses, we next evaluated the effects of blocking glycolysis with a pharmacological inhibitor, 2-DG, against lethal endotoxemia in an LPS-induced in vivo model of septic shock. Mice were treated i.p. with LPS at 10 mg/kg in the presence or absence of 2-DG, and mortality was monitored over an 80-h period. This high dose of LPS was chosen because it led to a mortality rate of >90% in WT B6 mice. The administration of 2-DG 6 h before the induction of septic shock conferred significant protection against lethal endotoxemia (Fig. 5A). Similarly, 2-DG treatment simultaneously reduced the serum levels of TNF-α and NO (Fig. 5 B and C). In agreement with the above findings, the deletion of HIF1α in cells of myeloid linage (LysM-Cre) significantly protected mice from death upon septic shock (Fig. 5D) and reduced the serum levels of TNF-α and NO (Fig. 5 E and F). One caveat of the above experiments is that both the systemic administration of 2-DG and the LysM-Cre–mediated deletion of HIF1α could affect the function of neutrophils. To address this concern, we first assessed the LysM-Cre activity using YFP reporter mice (R26-stop-EYFP) and found that a comparable percentage of macrophages and neutrophils were YFP+, indicating that HIF1α is deleted in both macrophages and neutrophils in LysM-Cre, HIF1αfl/fl mice (Fig. S5A). We further analyzed the distribution of immune cell populations before and after LPS treatment in WT and LysM-Cre, HIF1αfl/fl mice and observed that there was no difference in the percentages of examined cell types, before or after LPS treatment (Fig. S5B). Next, we examined the expression of TNFα in macrophages and neutrophils that were isolated from LPS-induced sepsis mice. Although the LysM-Cre–mediated deletion of HIF1α in the myeloid cell lineage or systemic administration of 2-DG significantly reduced TNFα expression in macrophages, HIF1α deletion in neutrophils had a mild and statistically insignificant effect on TNFα expression (Fig. S6A). Finally, we applied the Gr1 antibody to deplete neutrophils in both WT and LysM-Cre, HIF1αfl/fl mice and then challenged the mice with LPS. We found that neutrophil-depleted LysM-Cre, Hif-1αfl/fl mice displayed a significantly longer survival time compared with neutrophil-depleted WT mice (Fig. S6B), indicating that the protection conferred by HIF1α deletion is due to the macrophage, not neutrophil population. (Fig. S6B). Collectively, these data suggest that targeting HIF1α protects against experimental lethal endotoxic shock and sepsis partly by inhibiting glycolysis in macrophages.

Fig. 5.

Genetic deletion of HIF1α or pharmacologic blockage of glycolysis reduces severity of LPS-induced sepsis. (A–C) Age-matched BL6 mice were injected (i.p.) with PBS (solvent) or 2-DG (2 g/kg body weight) daily starting at 6 h before LPS (10 mg/kg) injection. The survival curve was plotted (A, n = 10). At 36 h, the serum was collected, and TNFα and NO levels were examined by ELISA and Greiss reagent, respectively (B and C). (D–F) Age-matched BL6 mice (WT) or LysM-Cre, HIF-1αflox/flox (KO) mice were injected (i.p.) with LPS (10 mg/kg). The survival curve was plotted (D, n = 10). At 36 h, the serum was collected, and TNFα and NO levels were examined by ELISA and Greiss reagent, respectively (E and F). Data are representative of two independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Fig. S5.

Characterization of LysM-Cre activities and LysM-Cre, HIF1αfl/fl mice. (A) The indicated organs were collected from LysM-Cre+LSL-YFP mice, the frequency of YFP+ cells was determined by FACS. (B) Age-matched BL6 mice (WT) or LysM-Cre, HIF-1αflox/flox (KO) mice were injected (i.p.) with solvent or LPS (10 mg/kg). At 36 h, the frequency of various immune populations in the indicated organ was determined by FACS. Data are representative of two independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Fig. S6.

Genetic deletion of HIF1α or pharmacologic blockage of glycolysis reduces severity of LPS-induced sepsis. (A) Age-matched BL6 mice (WT), LysM-Cre, HIF-1αflox/flox (KO) mice, or WT mice pretreated with 2-DG (as indicated in Fig. 5A) were injected (i.p.) with LPS (10 mg/kg). At 36 h, the TNFα expression in liver F4/80+ macrophages or Ly6G+ neutrophils was determined by FACS. (B) Age-matched BL6 mice (WT) and LysM-Cre, HIF-1αflox/flox (KO) mice were injected with 0.25 mg of anti-Gr1 antibody or IgG2b isotype control antibody at day −1 and day 3. Sepsis was induced by injecting 2 mg⋅kg−1 LPS at day 0. The survival curve was plotted (n = 10). The frequency of CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils in liver was determined by FACS.

Discussion

The proper development and function of all metazoan immune systems require the strict coordination of nutrient metabolism and bioenergetic capacity with immune cell proliferation and differentiation. Rapidly evolving pathogens exert a selective pressure on the integration of metabolism and immunity, which leads to the convergence of the signaling pathways that mediate nutrient processing (metabolism) and pathogen sensing (immunity). As such, our immune system is able to maintain homeostasis while remaining ready to elicit rapid and robust immune responses under diverse metabolic and immune conditions. As front-line effectors of innate immunity, macrophages can enter into the cell cycle upon mitogenic stimulation or can elicit a robust inflammatory response upon microbial challenge. Both the cell growth during proliferation and the cytokine production associated with the inflammatory response exhibit high bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands from macrophages. The inability to accommodate these demands would result in homeostatic imbalances in the immune system and possibly immunodeficiency and autoimmunity. We found that the Myc-dependent transcriptional program is responsible for cell cycle entry and the up-regulation of glucose and glutamine catabolism in BMDMs upon mitogenic stimulation. However, proinflammatory stimulation suppresses Myc-dependent cell proliferation while engaging a HIF1α-dependent transcriptional program to maintain heightened glycolysis in M1 macrophages. The switch between the Myc- and HIF1α-dependent transcriptional programs may ensure that inflammatory M1 macrophages have sufficient metabolic capacity to support their effector function, while limiting fuel use associated with cell proliferation. Whereas recent studies clearly demonstrate an essential role for metabolic reprogramming in inflammatory activation of macrophages (27, 38, 39), our studies implicate the switch in key transcriptional factors as an important mechanism of optimizing metabolic support during the inflammatory response.

The heightened glycolysis in proliferating or M1 macrophages is reminiscent of metabolic features in tumor cells, where aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) is driven by aberrant oncogenic signals (31, 40, 41). Acting alone or in concert, dysregulation of Myc and HIF1α, two key transcription factors that regulate the expression of metabolic genes, plays an essential role in reprograming metabolism to support tumor growth (30, 32, 42, 43). Notably, heightened aerobic glycolysis has also been implicated as a key metabolic feature of many immune cells, such as T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells, upon activation (44–46). Interestingly, the ligation of the T-cell receptors (TCR) or B-cell receptors (BCR) induces the expression of both Myc and HIF1α in T cells and B cells, respectively (33, 34). This change is also accompanied by a cell growth and proliferation burst after T- or B-cell activation. However, only Myc, but not HIF1α, is required for driving activation-induced T-cell or B-cell metabolic reprogramming (33, 34). In contrast, increased glycolysis is also seen in differentiating TH17 cells and during B-cell development in bone marrow, and this metabolic change is under the control of HIF1α (36, 47, 48). As such, the switch between the Myc- and HIF1α-dependent metabolic regulation in immunity may represent a general mechanism for fine-tuning metabolic homeostasis to support the divergent needs of immune function.

Emerging evidence has shown that a reconfiguration of glucose catabolism toward aerobic glycolysis and the pentose phosphate shunt (PPP) in M1 macrophages is integral to their host-defense properties (12, 17, 21, 25, 26). Glutaminolysis is a glutamine catabolic process during which the carbons of glutamine are oxidized and converted into CO2 and pyruvate largely through the TCA cycle in mitochondria (49, 50). One recent study revealed that glutamine is required for M2 polarization in macrophages. During LPS-stimulated M1 polarization, the integrated transcriptional-metabolic profiling revealed two metabolic break points in the metabolic flow of the TCA cycle, which suggests a defective TCA cycle and likely a suppressed glutaminolysis (51, 52). This finding is consistent with our finding of a reduction of glutamine oxidation in M1 macrophages. However, other specialized amino acid catabolic routes may be selectively induced in M1 macrophages. As such, the arginine catabolic pathway and recycling pathway have been implicated in dictating polarization and immune function of macrophages (53). Beyond this metabolic feature, the catabolism of GABA via the GABA shunt may play a critical role in channeling glutamate to the TCA cycle to provide succinate in M1 macrophages. Succinate, an anaplerotic substrate of the TCA cycle, may stabilize HIF1α and thus enhance its proinflammatory activity in M1 macrophages (16). In addition, genetic modulation of metabolic enzymes involved in glucose catabolism, such as PKM2, uPFK2, hexokinase (HK), and CARLK, significantly impacts on LPS-induced inflammatory immune responses in macrophages (21, 23–26). Collectively, these metabolic alterations enable the inflammatory functions of M1 macrophages. The manipulation of metabolic programs or their upstream regulatory signaling molecules can have a profound impact on the immune outcome.

Experimental Procedures

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and Fudan University. The detailed procedures of the endotoxin-induced model of sepsis, bone marrow-derived macrophage (BMDM) generation, qPCR analysis, Western blot analysis, metabolic activity analysis, and statistical analysis are described in SI Experimental Procedures.

SI Experimental Procedures

Animals.

HIF-1αflox/flox, ROSA26CreERT2, HIF-1αflox/flox, LysM-Cre, and Mycflox/flox, and ROSA26CreERAll mice are on the C57BL/6 background and were described previous (34, 54). C56BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson laboratory. The detailed procedures of the endotoxin-induced model of sepsis are described in the next paragraph. Mice at 8–12 wk of age were used in the experiment and were kept in specific pathogen-free conditions within the Animal Resource Center at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, or Fudan University. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and Fudan University.

Endotoxin-Induced Model of Sepsis.

Mice were treated with 2-DG (2 g⋅kg−1) or PBS for 6 h. Sepsis was induced by injecting 10 mg⋅kg−1 LPS, and survival was monitored. To deplete CD11b+Gr1+cells in vivo, 0.25 mg of anti-Gr1 antibody (RB6-8C5; eBioscience) or IgG2b isotype control antibody (eBioscience) was administered (i.p.) at day −1 and day 3. Sepsis was induced by injecting 2 mg⋅kg−1 LPS at day 0, and survival was monitored. Mice were killed immediately at a humane end point. In some experiments, the serum of experimental mice and the peritoneal F4/80+ macrophages (PEMs) was collected 36 h after LPS challenge. The level of TNFα and ALT in serum was determined by ELISA, the level of NO in sera was determined by Greiss assay, and the intracellular cytokine expression in PEMs was determined by FACS.

Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophage Generation, Stimulation, and Flow Cytometry.

To generate BMDMs, bone marrow was collected from femur and tibia bones. BMDMs were generated by culturing marrow cells in tissue culture dishes for 6 d with 30% (vol/vol) L929 fibroblast conditioned media and 70% (vol/vol) DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, 1× l-glutamine, and 1× penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic mix. BMDMs were left untreated as naive unstimulated macrophages or stimulated using 100 ng/mL LPS and 10 ng/mL IFNγ (M1) or 50 ng/mL CSF-1 (proliferation) for 12–24 h. In some experiments, BMDMs were cultured with 100% (vol/vol) DMEM with 1% FBS (CSF-1 starved) for 2 d before CSF-1 stimulation. The acute ablation of Myc or HIF-1α in BMDMs was achieved by incubating with 500 nM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (H7904; Sigma) for 2 d until any indicated treatment. At the end of incubations, BMDMs were harvested with a cell scraper, counted, and processed for the following assays. For cell cycle analysis, BMDMs were suspended with 200 μL of hypotonic buffer that contained 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium citrate, 50 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma), and 5 μL of APC-p-Histone H3 (BD Bioscience) for 20 min. Flow cytometry data were acquired on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) and were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

qPCR and Western Blot Analysis.

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and was reverse transcripted using random hexamer and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). SYBR green-based quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the Applied Biosystems 7900 Real Time PCR System. The relative gene expression was determined by the comparative CT method, also referred to as the 2−ΔΔCT method. The data were presented as the fold change in gene expression normalized to an internal reference gene (beta2-microglobulin) and relative to the control (the first sample in the group): fold change = 2−ΔΔCT = [(CTgene of interst − CTinternal reference)]sample A = [(CTgene of interst − CTinternal reference)]sample B. Samples for each experimental condition were run in triplicate PCR reactions. Primer sequences were obtained from PrimerBank (55). Primer sequences are listed in Table S2. Cell extracts were prepared and immunoblotted as previously described (56). The antibodies and reagents are listed in Table S1.

Table S2.

Genes

| Gene name | Primer-forward | Primer-reverse |

| Beta2microglobulin | TTCTGGTGCTTGTCTCACTGA | CAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTC |

| c-Myc | TTGAAGGCTGGATTTCCTTTGGGC | TCGTCGCAGATGAAATAGGGCTGT |

| HIF1a | AGCTTCTGTTATGAGGCTCACC | TGACTTGATGTTCATCGTCCTC |

| Slc2a1(Glut1) | CAGTTCGGCTATAACACTGGTG | GCCCCCGACAGAGAAGATG |

| HK2 | TGATCGCCTGCTTATTCACGG | AACCGCCTAGAAATCTCCAGA |

| LDHa | CATTGTCAAGTACAGTCCACACT | TTCCAATTACTCGGTTTTTGGGA |

| PKM2 | GCCGCCTGGACATTGACTC | CCATGAGAGAAATTCAGCCGAG |

| Slc7a5 | CCGGTCTTCCCCACTTGTC | CTTGTCCCATGTCCTTCCCC |

| SLC3a2 | TGATGAATGCACCCTTGTACTTG | TCCCCAGTGAAAGTGGA |

| MCT4 | TCACGGGTTTCTCCTACGC | GCCAAAGCGGTTCACACAC |

| Pfkfb3 | CCCAGAGCCGGGTACAGAA | GGGGAGTTGGTCAGCTTCG |

| Pfkl | GGAGGCGAGAACATCAAGCC | CGGCCTTCCCTCGTAGTGA |

| ME2 | AAGGGAATGGCGTTTACGTTAC | GTACACAATCGGCATCAGACTT |

| Tpi | CCAGGAAGTTCTTCGTTGGGG | CAAAGTCGATGTAAGCGGTGG |

| Enolase 1 | TGCGTCCACTGGCATCTAC | CAGAGCAGGCGCAATAGTTTTA |

| CAD | CTGCCCGGATTGATTGATGTC | GGTATTAGGCATAGCACAAACCA |

| Cdk4 | ATGGCTGCCACTCGATATGAA | TCCTCCATTAGGAACTCTCACAC |

| Cdc25a | ACAGCAGTCTACAGAGAATGGG | GATGAGGTGAAAGGTGTCTTGG |

| Cyclin D3 | CGAGCCTCCTACTTCCAGTG | GGACAGGTAGCGATCCAGGT |

| Cyclin E1 | GTGGCTCCGACCTTTCAGTC | CACAGTCTTGTCAATCTTGGCA |

| Ogdh | GGAACTGCCCTCTAGGGAGA | GACGCTACCACTGTTAATGACC |

| FH1 (fumarate hydratase 1) | GAATGGCAAGCCAAAATTCCTT | CGTTCTGTAGCACCTCCAATCTT |

| Cs | GGACAATTTTCCAACCAATCTGC | TCGGTTCATTCCCTCTGCATA |

| Aco1 | AGAACCCATTTGCACACCTTG | AGCGTCCGTATCTTGAGTCCT |

| Aco2 | ATCGAGCGGGGAAAGACATAC | TGATGGTACAGCCACCTTAGG |

| IDH1 | ATGCAAGGAGATGAAATGACACG | GCATCACGATTCTCTATGCCTAA |

| IDH2 | CACCGTCCATCTCCACTACC | CAGCACTGACTGTCCCCAG |

| GOT2 | TGGGCGAGAACAATGAAGTGT | CCCAGGATGGTTTGGGCAG |

| GPT | TCCAGGCTTCAAGGAATGGAC | CAAGGCACGTTGCACGATG |

| Glud1 | CCCAACTTCTTCAAGATGGTGG | AGAGGCTCAACACATGGTTGC |

| SDHa | GGAACACTCCAAAAACAGACCT | CCACCACTGGGTATTGAGTAGAA |

| SDHb | GCTGCGTTCTTGCTGAGACA | ATCTCCTCCTTAGCTGTGGTT |

| SDHc | TGGTCAGACCCGCTTATGTG | GGTCCAGTGGAGAGATGCAG |

| Slc1a5 | GGTCTCCTGGATTATGTGGTACG | AGCACAGAATGTATTTGCCGAG |

| Gls | GGGAATTCACTTTTGTCACGA | GACTTCACCCTTTGATCACC |

| Gls2 | AGCGTATCCCTATCCACAAGTTCA | GCAGTCCAGTGGCCTTCAGAG |

| MDH | GGCACAGCCTTGGAGAAATAC | AGCGAGTCAGGCAACTGAAAT |

| MDH2 | TTGGGCAACCCCTTTCACTC | GCCTTTCACATTTGCTCTGGTC |

| PDHe2 | TCCCTCCGCATCAGAAGGTT | CCAACTGGAACATCTCTGGTC |

| PDHx | GTGCTGGAGACTCGTTATGTG | CCTGTTTCCAATCTTCCCCTTC |

| PDK1 | GGACTTCGGGTCAGTGAATGC | TCCTGAGAAGATTGTCGGGGA |

| Slc38a1 | CCTTCACAAGTACCAGAGCAC | GGCCAGCTCAAATAACGATGAT |

| DLST | GGAACTGCCCTCTAGGGAGA | GACGCTACCACTGTTAATGACC |

| DLD | GAGCTGGAGTCGTGTGTACC | CCTATCACTGTCACGTCAGCC |

Table S1.

Reagents and antibodies

| Name | Cat. no./vendor |

| Reagent | |

| Tamoxifen | Sigma |

| 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) | D4601/Sigma |

| [3-3H]-Glucose | NET331A/PerkinElmer |

| [U-14C]-Glutamine | MC 1124/Moravek |

| [2-14C]-Pyruvate | MC 1343/Moravek |

| [1-14C]-Glucose | MC 228/Moravek |

| LPS | 055:B5/Sigma-Aldrich |

| IFN-gamma | PeproTech |

| M-CSF | PeproTech |

| Antibody | |

| Anti-actin | C4/MP |

| Anti-Glut1 | 07–1401/Millipore |

| Myc | 9402 or 5605/Cell Signaling |

| Hif1a | 10006421/Cayman Chemicals |

| Cyclin D3 | 2936/Cell Signaling |

| CDK4 | sc260/Santa Cruz |

| Cdc25a | sc7389/Santa Cruz |

| pHistone H3-APC | BD Bioscience |

| Anti-Gr1 | RB6-8C5/eBioscience |

| IgG2b isotype control antibody | eBioscience |

Metabolic Activity Analysis.

Glycolytic activity was determined by measuring the detritiation of [3-3H]-glucose (57). In brief, one million stimulated or unstimulated BMDMs were suspended in 0.5 mL of fresh media. The experiment was initiated by adding 1 μci of [3-3H]-glucose, and, 2 h later, media were transferred to a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube containing 50 μL of 5 M HCl. The microcentrifuge tubes were then placed in 20-mL scintillation vials containing 0.5 mL of water, with the vials capped and sealed. 3H2O was separated from unmetabolized [3-3H]-glucose by evaporation diffusion for 24 h at room temperature. A cell-free sample containing 1 μci of [3-3H]-glucose was included as a background control.

Glutamine oxidation activity was determined by the rate of 14CO2 released from [U-14C]-glutamine (58). In brief, five million stimulated or unstimulated BMDMs were suspended in 1 mL of fresh media. To facilitate the collection of 14CO2, cells were dispensed into 7-mL glass vials (TS-13028; Thermo) with a PCR tube containing 50 μL of 0.2 M KOH glued on the sidewall. After adding 0.5 μci of [U-14C]-glutamine, the vials were capped using a screw cap with rubber septum (TS-12713; Thermo). The assay was stopped 2 h later by injection of 100 μL of 5 M HCl, and the vials were kept at room temperate overnight to trap the 14CO2. The 50 μL of KOH in the PCR tube was then transferred to scintillation vials containing 10 mL of scintillation solution for counting. A cell-free sample containing 0.5 μci of [U-14C]-glutamine was included as a background control.

Pyruvate oxidation activity was determined by the rate of 14CO2 released from [2-14C]-pyruvate (59). In brief, five million stimulated or unstimulated BMDMs were suspended in 1 mL of fresh T-cell media. To facilitate the collection of 14CO2, cells were dispensed into 7-mL glass vials (TS-13028; Thermo) with a PCR tube containing 50 μL of 0.2 M KOH glued on the sidewall. After adding 0.5 μci of [2-14C]-pyruvate, the vials were capped using a screw cap with rubber septum (TS-12713; Thermo). The assay was stopped 2 h later by injection of 100 μL of 5 M HCl, and the vials were kept at room temperate overnight to trap the 14CO2. The 50 μL of KOH in the PCR tube was then transferred to scintillation vials containing 10 mL of scintillation solution for counting. A cell-free sample containing 0.5 μci of [2-14C]-pyruvate was included as a background control.

Statistical Analysis.

P values were calculated with two-tailed Student's t test (Excel). P values of <0.05 were considered significant in all analyses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants R21AI117547 and 1R01AI114581, V Foundation Grant V2014-001, American Cancer Society Grant 128436-RSG-15-180-01-LIB (to R.W.), National Natural Science Foundation for General Programs of China Grants 31171407 and 81273201 (to G. Liu), the American Lebanese and Syrian Associated Charities, and other grants from the NIH (to D.R.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1518000113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: Developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(6):392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sieweke MH, Allen JE. Beyond stem cells: Self-renewal of differentiated macrophages. Science. 2013;342(6161):1242974. doi: 10.1126/science.1242974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newsholme EA, Crabtree B, Ardawi MS. The role of high rates of glycolysis and glutamine utilization in rapidly dividing cells. Biosci Rep. 1985;5(5):393–400. doi: 10.1007/BF01116556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: Metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7(1):11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw RJ. Glucose metabolism and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18(6):598–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brand K. Aerobic glycolysis by proliferating cells: Protection against oxidative stress at the expense of energy yield. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1997;29(4):355–364. doi: 10.1023/a:1022498714522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(12):958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(11):723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vadiveloo PK, Keramidaris E, Morrison WA, Stewart AG. Lipopolysaccharide-induced cell cycle arrest in macrophages occurs independently of nitric oxide synthase II induction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1539(1-2):140–146. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vadiveloo PK. Macrophages: Proliferation, activation, and cell cycle proteins. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66(4):579–582. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton JA. CSF-1 and cell cycle control in macrophages. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46(1):19–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199701)46:1<19::AID-MRD4>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newsholme P, Costa Rosa LF, Newsholme EA, Curi R. The importance of fuel metabolism to macrophage function. Cell Biochem Funct. 1996;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/cbf.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odegaard JI, Chawla A. The immune system as a sensor of the metabolic state. Immunity. 2013;38(4):644–654. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNelis JC, Olefsky JM. Macrophages, immunity, and metabolic disease. Immunity. 2014;41(1):36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas SK. Metabolic reprogramming of immune cells in cancer progression. Immunity. 2015;43(3):435–449. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tannahill GM, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature. 2013;496(7444):238–242. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stubbs M, Kühner AV, Glass EA, David JR, Karnovsky ML. Metabolic and functonal studies on activated mouse macrophages. J Exp Med. 1973;137(2):537–542. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galván-Peña S, O’Neill LA. Metabolic reprograming in macrophage polarization. Front Immunol. 2014;5:420. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bordbar A, et al. Model-driven multi-omic data analysis elucidates metabolic immunomodulators of macrophage activation. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8:558. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freemerman AJ, et al. Metabolic reprogramming of macrophages: Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1)-mediated glucose metabolism drives a proinflammatory phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(11):7884–7896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.522037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haschemi A, et al. The sedoheptulose kinase CARKL directs macrophage polarization through control of glucose metabolism. Cell Metab. 2012;15(6):813–826. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maeng O, et al. Cytosolic NADP(+)-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase protects macrophages from LPS-induced nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317(2):558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodríguez-Prados JC, et al. Substrate fate in activated macrophages: A comparison between innate, classic, and alternative activation. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):605–614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cramer T, et al. HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 2003;112(5):645–657. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palsson-McDermott EM, et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates Hif-1α activity and IL-1β induction and is a critical determinant of the warburg effect in LPS-activated macrophages. Cell Metab. 2015;21(1):65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang L, et al. PKM2 regulates the Warburg effect and promotes HMGB1 release in sepsis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4436. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palazon A, Goldrath AW, Nizet V, Johnson RS. HIF transcription factors, inflammation, and immunity. Immunity. 2014;41(4):518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuckey DJ, et al. Detection of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA in macrophages by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78(2):393–400. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1203604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newsholme P, Gordon S, Newsholme EA. Rates of utilization and fates of glucose, glutamine, pyruvate, fatty acids and ketone bodies by mouse macrophages. Biochem J. 1987;242(3):631–636. doi: 10.1042/bj2420631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dang CV. The interplay between MYC and HIF in the Warburg effect. Ernst Schering Found Symp Proc. 2007;2007(4):35–53. doi: 10.1007/2789_2008_088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dang CV, Semenza GL. Oncogenic alterations of metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24(2):68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordan JD, Thompson CB, Simon MC. HIF and c-Myc: sibling rivals for control of cancer cell metabolism and proliferation. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(2):108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caro-Maldonado A, et al. Metabolic reprogramming is required for antibody production that is suppressed in anergic but exaggerated in chronically BAFF-exposed B cells. J Immunol. 2014;192(8):3626–3636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang R, et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity. 2011;35(6):871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dang EV, et al. Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;146(5):772–784. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi LZ, et al. HIF1alpha-dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208(7):1367–1376. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roussel MF, Cleveland JL, Shurtleff SA, Sherr CJ. Myc rescue of a mutant CSF-1 receptor impaired in mitogenic signalling. Nature. 1991;353(6342):361–363. doi: 10.1038/353361a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray PJ, Rathmell J, Pearce E. SnapShot: Immunometabolism. Cell Metab. 2015;22(1):190–190.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Neill LA, Hardie DG. Metabolism of inflammation limited by AMPK and pseudo-starvation. Nature. 2013;493(7432):346–355. doi: 10.1038/nature11862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(2):85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang LE. Carrot and stick: HIF-alpha engages c-Myc in hypoxic adaptation. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(4):672–677. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H, et al. HIF-1 inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis and cellular respiration in VHL-deficient renal cell carcinoma by repression of C-MYC activity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(5):407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krawczyk CM, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2010;115(23):4742–4749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho SH, et al. Glycolytic rate and lymphomagenesis depend on PARP14, an ADP ribosyltransferase of the B aggressive lymphoma (BAL) family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(38):15972–15977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017082108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frauwirth KA, et al. The CD28 signaling pathway regulates glucose metabolism. Immunity. 2002;16(6):769–777. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michalek RD, et al. Cutting edge: Distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J Immunol. 2011;186(6):3299–3303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kojima H, et al. Differentiation stage-specific requirement in hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-regulated glycolytic pathway during murine B cell development in bone marrow. J Immunol. 2010;184(1):154–163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeBerardinis RJ, et al. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: Transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19345–19350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newsholme EA, Crabtree B, Ardawi MS. Glutamine metabolism in lymphocytes: Its biochemical, physiological and clinical importance. Q J Exp Physiol. 1985;70(4):473–489. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1985.sp002935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jha AK, et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity. 2015;42(3):419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Orchestration of metabolism by macrophages. Cell Metab. 2012;15(4):432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qualls JE, et al. Sustained generation of nitric oxide and control of mycobacterial infection requires argininosuccinate synthase 1. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(3):313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu G, et al. Dendritic cell SIRT1-HIF1α axis programs the differentiation of CD4+ T cells through IL-12 and TGF-β1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(9):E957–E965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420419112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spandidos A, Wang X, Wang H, Seed B. PrimerBank: A resource of human and mouse PCR primer pairs for gene expression detection and quantification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(Database issue):D792–D799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He G, et al. Induction of p21 by p53 following DNA damage inhibits both Cdk4 and Cdk2 activities. Oncogene. 2005;24(18):2929–2943. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hue L, Sobrino F, Bosca L. Difference in glucose sensitivity of liver glycolysis and glycogen synthesis: Relationship between lactate production and fructose 2,6-bisphosphate concentration. Biochem J. 1984;224(3):779–786. doi: 10.1042/bj2240779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brand K, Williams JF, Weidemann MJ. Glucose and glutamine metabolism in rat thymocytes. Biochem J. 1984;221(2):471–475. doi: 10.1042/bj2210471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willems HL, de Kort TF, Trijbels FJ, Monnens LA, Veerkamp JH. Determination of pyruvate oxidation rate and citric acid cycle activity in intact human leukocytes and fibroblasts. Clin Chem. 1978;24(2):200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]