Abstract

Background

Within the past decade, healthcare service and research priorities have shifted from evidence-based medicine to personalized medicine. In mental healthcare, a similar shift to personalized intervention may boost the effectiveness and clinical utility of empirically supported therapies (ESTs).

Aims and Scope

The emerging science of personalized intervention will need to encompass evidence-based methods for determining which problems to target and in which order, selecting treatments and deciding whether and how to combine them, and informing ongoing clinical decision-making through monitoring of treatment response throughout episodes of care. We review efforts to develop these methods, drawing primarily from psychotherapy research with youths. Then we propose strategies for building a science of personalized intervention in youth mental health.

Findings

The growing evidence base for personalizing interventions includes research on therapies adapted for specific subgroups; treatments targeting youths’ environments; modular therapies; sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trials; measurement feedback systems; meta-analyses comparing treatments for specific patient characteristics; data-mining decision trees; and individualized metrics.

Conclusion

The science of personalized intervention presents questions that can be addressed in several ways. First, to evaluate and organize personalized interventions, we propose modifying the system used to evaluate and organize ESTs. Second, to help personalizing research keep pace with practice needs, we propose exploiting existing randomized trial data to inform personalizing approaches, prioritizing the personalizing approaches likely to have the greatest impact, conducting more idiographic research, and studying tailoring strategies in usual care. Third, to encourage clinicians’ use of personalized intervention research to inform their practice, we propose expanding outlets for research summaries and case studies, developing heuristic frameworks that incorporate personalizing approaches into practice, and integrating personalizing approaches into service delivery systems. Finally, to build a richer understanding of how and why treatments work for particular individuals, we propose accelerating research to identify mediators within and across RCTs, to isolate mechanisms of change, and to inform the shift from diagnoses to psychopathological processes. This ambitious agenda for personalized intervention science, though challenging, could markedly alter the nature of mental health care and the benefit provided to youths and families.

Keywords: children, adolescents, psychotherapy, personalized intervention, tailoring treatments

Introduction

The past decade has witnessed a shift in healthcare service and research priorities from evidence-based medicine to personalized medicine. Evidence-based medicine emphasizes using research findings, such as the results of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses of treatment outcome studies, together with clinical expertise and patient preferences, to make clinical decisions about individual patients (Sackett, Straus, Richardson, Rosenberg, & Haynes, 2000). Personalized medicine goes a step further by providing evidence-based methods for translating research findings into individual treatment plans. For example, the discovery of oncogenic drivers (i.e., genetic mutations or rearrangements that drive tumor growth) which vary across individuals have ushered in a new era of personalized cancer diagnostics and treatment (Collins & Varmus, 2015; Hamburg & Collins, 2010). Drugs designed to target specific oncogenic drivers have dramatically increased response and survival rates compared to standard treatment (i.e., chemotherapy) among individuals carrying those drivers; therefore, it is now standard practice for patients with lung, breast, and other cancers to undergo genetic testing, and for oncologists to select treatments based on patients’ genetic profiles (e.g., Okimoto & Bivona, 2014).

In mental healthcare, a similar shift to personalized intervention is underway (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], 2008, 2015). Although constructing and carrying out individualized treatments have long been central to mental health practice (British Psychological Society, 2011; Eells, 2007; Winters, Hanson, & Stoyanova, 2007), efforts to develop methods for individualizing treatments that are supported by research have intensified in recent years. Evidence-based methods for tailoring treatments to individuals are what we refer to as personalized interventions.

In this review, we first describe personalized intervention for mental health problems (including diagnosable disorders and elevated symptoms) and a rationale for the personalized intervention movement. Then we review current research efforts to personalize interventions, focusing on those involving child and adolescent (herein, “youth”) psychotherapies. We conclude with questions and proposals central to advancing personalized intervention science.

What is Personalized Intervention for Mental Health Problems?

Like personalized medicine for physical conditions, personalized intervention for mental health problems includes as critical components reliable assessment of clinically relevant individual characteristics and treatments tailored for individuals who share those characteristics to optimize treatment gains. However, there are notable differences.

The personalized medicine movement was catalyzed by research identifying individual differences in genetic makeup that differentially influence disease-related mechanisms; hence, research focuses on designing drugs that target mechanisms associated with specific genetic variants and developing “companion diagnostics” of those variants (Hamburg & Collins, 2010). Clinical applications of personalized medicine involve administering diagnostic tests to categorize individuals into subgroups that differ in some biological disease-related mechanism, and, thus, differ in expected response to particular drugs; then, prescribing the drug targeting the identified mechanism.

In mental health, there is currently insufficient empirical basis for the subgroup approach defined by underlying genetic or biological mechanisms, which predominates in personalized medicine (Insel & Cuthbert, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2010; Simon & Perlis, 2010). However, there is a growing evidence base on other approaches to personalizing mental health interventions.1 These approaches may involve prioritizing or integrating multiple predictors of treatment engagement or impact (e.g., comorbidity, motivation for change, treatment history) in a way that facilitates treatment planning. Alternatively, personalizing approaches may include selecting psychotherapy, psychoactive medication, or another efficacious treatment (e.g., deep brain stimulation); deciding whether to combine interventions and, if so, how to sequence them; and choosing psychotherapy techniques to use, problems or psychological/behavioral mechanisms to target, and the temporal order of technique or problem. Finally, interventions may be personalized via continual assessment of patient response and side effects to guide clinical decisions. Hence, intervention may not only be matched or tailored at the outset based on patient characteristics, but also adaptive—that is, adjusted according to the patient's treatment response over time (Lei, Nahum-Shani, Lynch, Oslin, & Murphy, 2012). We focus on personalizing approaches involving youth psychotherapy partly because of their documented efficacy for treating many mental health problems (for another review with greater focus on medication, see Fisher & Bosley, 2015). Furthermore, psychotherapy lacks side effects and can reduce serious side effects (Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study Team, 2007) and required dosage (Pelham et al., 2005) of concurrent medications, which are important considerations for youths undergoing physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development.

Why Personalize Interventions?

Efforts to personalize interventions build in part on earlier work to identify and disseminate empirically supported therapies (ESTs; Chambless et al., 1998; Kendall, 1998). Responding to the proliferation of psychotherapies being practiced with no clear evidence of benefit, some psychologists pushed to develop and identify ESTs: “clearly specified psychological treatments shown to be efficacious in controlled research with a delineated population” (Chambless & Hollon, 1998, p. 7). Criteria for ESTs—together with policies of some major research funders—have encouraged treatment developers to create psychotherapies targeting single disorders or relatively homogeneous problem clusters (e.g., anxiety-related problems), document their procedures in manuals, test them against a control group or another treatment, and assess outcomes using reliable and valid measures. Today, ESTs exist for many youth and adult mental health problems, reflecting the remarkable progress made in building an evidence base for psychotherapies.2

Empirically Supported Therapies and the Personalizing Challenge

Notwithstanding this impressive progress, considerable work remains on the personalizing front. RCTs have focused on whether the target treatment group improves more than a comparison group, on average; accordingly, EST protocols have tended to standardize rather than individualize treatment and assessment (Persons, 1991, 2013). The procedures specified in an EST manual are usually prescribed for all patients who have the target problem, following a standard linear, session-by-session sequence. EST manuals may encourage some degree of personalization such as finding examples that interest a particular youth, sequencing activities based on their difficulty level for a youth, and letting the youth choose rewards for accomplishing therapy goals. Nevertheless, manuals typically lack detailed instructions on how to assess and handle comorbidities that warrant intervention, how to address problems interfering with the prescribed treatment sequence, how to utilize new information uncovered during treatment that changes the diagnostic picture or that calls for a new plan, how to respond when new and urgent treatment needs surface, and what to do if a crisis threatens to completely derail the manualized treatment (Weisz & Chorpita, 2011). One tradeoff in our search for ESTs is that we researchers may have learned a lot about producing treatment benefit, on average, at the expense of personalizing intervention to optimally benefit each individual.

Limitations of Empirically Supported Therapies

The restricted customizability of some ESTs may have limited their effectiveness relative to usual clinical care, which is often highly individualized. Two recent meta-analyses (Weisz, Jensen-Doss, & Hawley, 2006; Weisz, Kuppens, et al., 2013) of youth RCTs that pitted ESTs against usual care found only small to medium effects (d = .30 and .29 respectively). Although significantly greater than zero, both effect sizes indicate that a randomly selected youth receiving an EST only had a 58% probability of doing better than a randomly selected youth receiving usual care. In fact, another meta-analysis (Spielmans, Gatlin, & McFall, 2010) showed that the modest superiority of youth ESTs over usual care may be further diminished by controlling for several confounds.

In addition, the broader societal impact of ESTs is constrained by how widely the ESTs can be disseminated to families and service providers and how well they can be implemented in everyday practice settings. To date, the literature does not paint a very bright picture of EST dissemination and implementation within usual practice. Observations of videotaped therapy sessions have revealed low-level usage of ESTs in routine care of youths (Garland et al., 2010; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010; Weisz et al., 2009, 2012). One barrier to clinicians’ use of ESTs is their concern that manuals are too rigid and need to be modified for individual patients’ needs and preferences (Addis & Krasnow, 2000; Gyani, Shafran, Rose, & Lee, 2013; Jensen-Doss, Hawley, Lopez, & Osterberg, 2009), even among clinicians unopposed to evidence-based practices per se (Borntrager, Chorpita, Higa-McMillan, & Weisz, 2009; Thomas, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Chaffin, 2014). Unsurprisingly, clinicians reported being more likely to adopt treatments with built-in flexibility to address the severity, complexity, and comorbidity that are so common among referred youths, and to navigate the zigs and zags of treatment episodes in real-life clinical care (Nelson, Steele, & Mize, 2006).

Current Research Directions in Personalizing Interventions

Although the idea of personalizing interventions has intuitive appeal, not all interventions that have been tailored to individual patients have been successful. Individualized therapies have outperformed standardized therapies in some studies (Ghaderi, 2006; Jacobson et al., 1989; Weisz et al., 2012) but underperformed in others (Chaffin et al., 2004; Schulte, Künzel, Pepping, and Schulte-Bahrenberg, 1992). These findings, and clinicians’ preference for individual tailoring of therapies, underscore the need to develop and test personalizing approaches. Here, we describe eight current themes in the growing evidence base on personalizing interventions, using examples from youth psychotherapy where available. These themes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eight strategies in the evidence base for Personalizing Mental Health Interventions

| Strategy | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Therapies Adapted for Specific Subgroups | Empirically supported therapies (ESTs) adapted to improve outcomes or engagement in subgroups of individuals expected to respond poorly to ESTs. | Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT), an EST for disruptive behavior, adapted for Mexican American families; outperformed nonadapted PCIT at follow-up (McCabe & Yeh, 2009; McCabe et al., 2005, 2012). |

| Therapies Targeting Youths’ Environments | ESTs that alter or leverage environments (e.g., family, school, peers) thought to impact youth outcomes; therapists conduct treatment at least partly within these environments using formats tailored to patient needs, based on individualized goals. | Multisystemic Therapy, an EST for both delinquent and substance-abusing adolescents that is widely disseminated (Henggeler, 2011; Henggeler & Schaeffer, 2010; Schoenwald, 2010). |

| Modular Therapies | ESTs organized into self-contained modules that can be used multiple times or not at all, and combined as needed; decision-making flowcharts guide which modules to use and when to use them for a particular patient. | Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems; outperformed standard ESTs at posttreatment and usual care at posttreatment and follow-up (Chorpita & Weisz, 2009; Weisz et al., 2012; Chorpita et al., 2013). |

| Sequential, Multiple Assignment, Randomized Trials (SMARTs) | A trial design that randomizes individuals to a first-stage treatment or assessment condition, assesses response, then potentially randomizes individuals to next-stage treatment options based on their response; generates evidence for constructing decision rules in sequencing treatments. | A SMART of minimally verbal children with autism found superior outcomes for communication intervention augmented by a speech-generating device (vs. non-augmented intervention), and, for nonresponders after three months, intensified augmented intervention (vs. intensified non-augmented intervention; Kasari et al., 2014). |

| Measurement Feedback Systems | A system of administrating assessments of treatment outcomes and progress indicators that are psychometrically sound, sensitive to clinical change, brief, and clinically useful; then storing and displaying the data in meaningful formats to provide feedback about how well treatment is working. | The Youth Outcome Questionnaire and Youth Outcome Questionnaire Self-Report have identified youths at-risk of treatment failure; Youth-Clinical Support Tools pinpoint obstacles and suggest solutions (Burlingame et al., 2001; Cannon et al., 2010; Ridge et al., 2009; Warren & Lambert, 2012; Warren et al., 2012). |

| Meta-analyses Comparing Treatments for Specific Patient Characteristics | Research syntheses of randomized trials comparing alternative treatment strategies or types directly (i.e., within the same trial) among patients with specific characteristics. | A meta-analysis compared psychotherapy, medication, and combination psychotherapy-medication for subgroups of depressed adults and found sufficient evidence to recommend medication for dysthymia and combination treatment for older adults and outpatients (Cuijpers et al., 2012). |

| Data-mining Decision Trees | Models that guide decision-making based on multiple characteristics of individuals; developed through data mining, an exploratory approach for detecting and interpreting patterns in data. | The Distillation and Matching Model mined data from youth psychotherapy trials to develop a tool to select efficacious treatments, or their elements, based on patient characteristics; produced medium-large pre-post effects as part of a comprehensive service model (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2013; Chorpita et al., 2005; Southam-Gerow et al., 2013). |

| Individualized Metrics | Indices that quantify the benefit each patient is expected to receive from alternative interventions by accounting for one or more characteristics of the patient. | Probability of treatment benefit (PTB) was computed for a randomized trial of youth anxiety treatments at different levels of pretreatment symptom severity; PTB differed across treatments only for severe anxiety, with highest PTB for combination CBT-SSRI (Beidas et al., 2014; Lindhiem et al., 2012). |

Therapies Adapted3 for Specific Subgroups

Probably the most commonly evaluated approach with youths has been to identify a subgroup (e.g., of a particular culture, with specific comorbidities) expected to respond poorly to existing ESTs, and then to adapt existing ESTs for that subgroup. We illustrate this approach with therapies adapted for youths from specific cultures.

Because most youth ESTs have been developed and tested with mainly Caucasian samples, the concepts, examples, and language used may be unfamiliar to or discordant with other cultures. Some researchers (e.g., Hall, 2001) have called for cultural adaptations of ESTs. Adaptation may involve modifying language, cultural, and contextual elements to make ESTs consistent with patients’ experiences and perspectives (Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey, & Rodríguez, 2009). For example, Parent-Child- Interaction Therapy (PCIT), an EST for child disruptive behavior, was adapted for Mexican American families to increase their engagement while retaining core treatment techniques (Lau, 2006; McCabe, Garland, Yeh, Lau, & Chavez, 2005). Treatment began with a cultural assessment to understand parent perceptions of their child's problems, appropriate discipline, stigma around seeking mental health services, other family members’ roles in parenting and in treatment, and treatment expectations. Treatment presentation was then tailored to fit each family's perspective. Adaptations included calling a chair used for time-out a “punishment chair” or “thinking chair” depending on parents’ beliefs about discipline, presenting treatment as an educational program to reduce stigma, allocating extra time to build rapport given the high value many Mexican Americans place on warm relationships, routinely soliciting complaints that Mexican Americans might avoid given their purported respect for authority, and actively engaging family members (e.g., fathers, grandparents) considered likely to influence decisions about continuing treatment. Adapted PCIT and nonadapted PCIT both outperformed usual care controls at posttreatment, but only adapted PCIT outperformed usual care on externalizing problems at 6-to-24-month follow-up (McCabe & Yeh, 2009; McCabe, Yeh, Lau, & Argote, 2012). However, a recent review (Huey, Tilley, Jones, & Smith, 2014) found insufficient and inconsistent evidence on whether cultural adaptations confer incremental benefit. For example, culturally adapting CBT for adolescent substance use had advantages only for the subset of Latino youths with strong ethnic identity and familism (i.e., attachment to and identification with one's family; Burrow-Sanchez & Wrona, 2012), whereas culturally adapting Structural Family Therapy had no advantage for Cuban American youths (Szapocznik et al., 1986). These mixed findings may reflect heterogeneity (i.e., benefit is associated only with some adaptations, therapies, disorders, or cultures), or simply chance deviations from a mean adaptation effect of zero. Evidence is also mixed on whether efficacious adapted therapies enhance benefit for only the targeted subgroup or for young patients in general—in the second case, the adaptations would represent overall treatment refinement rather than successful personalization for the subgroup (Huey et al., 2014). Clearly, important questions remain for future study.

Therapies Targeting Youths’ Environments

Typical ESTs comprise weekly 50-minute clinic sessions attended by the youth or caregiver, aim at changing the attendees’ behavior. In contrast, certain ESTs seek to alter or leverage environments—school, family, peers, neighborhood, community, employment, and legal contexts—thought to impact youth outcomes. Using treatment principles and individualized goals, therapists custom-build a program for each youth and conduct treatment partly or fully within these environments, using formats tailored to patient needs. Examples include Treatment Foster Care Oregon (TFCO, formerly known as Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care; Smith & Chamberlain, 2010) for severely delinquent youths, Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT; Liddle, 2010) for substance-abusing adolescents, and Multisystemic Therapy (MST; Henggeler & Schaeffer, 2010) for both delinquent and substance-abusing youths.

MST (Henggeler & Schaeffer, 2010), for example, is based on a social ecological model, which posits that risk factors within youths’ environments and conflicts between environments drive delinquency, and that treatment success depends on removing these drivers. Case formulation incorporates the youth's delinquent behaviors identified by “key persons” in the youth's life (e.g., truancy identified by school staff), drivers of those behaviors (e.g., delinquent peers, poor academic ability), and strengths that could potentially be leveraged for driver removal (e.g., supervised recreation for neighborhood youths could substitute time spent with delinquent peers, career ambitions could motivate academic achievement). The therapist then integrates multiple evidence-based interventions and practical assistance to target the drivers for a particular youth's delinquency (e.g., behavioral parent training to improve monitoring of youths, motivational interviewing to prompt parent or youth behavioral change). Assessments and interventions occur in the youth's everyday environments; key persons serve as first-hand informants and deliver much of the intervention to the youth, guided by the therapist. In addition, the therapists are available 24/7 to accommodate families’ schedules and respond quickly to crises. Treatment progress is monitored to provide feedback—if hypothesized drivers were eliminated but the delinquent behavior remained, the drivers are reconceptualized and suitable interventions delivered, until the delinquent behavior is managed or eliminated. Notably, MST has been adapted for different populations, such as youths who were abused and those with chronic health conditions (Henggeler, 2011).

Modular Therapies

Recently, modular psychotherapy protocols have emerged, providing a structured approach to tailoring ESTs to fit patient needs. Treatment strategies for multiple problems are organized into self-contained modules that can be used multiple times or not at all, and can be combined as needed; clinical decision-making flowcharts guide which modules to use and when to use them for a particular patient. Thus, treatment of any two patients may involve different modules, or similar modules in different order.

An example is the Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems (MATCH), which targets youths who have any one, or any combination, of these problems (Chorpita & Weisz, 2009). MATCH comprises modules drawn from ESTs for the four problem areas—cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety, depression, and trauma; and behavioral parent training for conduct problems. Four decision flowcharts, each designed for one primary problem but containing modules from all four ESTs, guide therapists’ use of modules in a flexible manner. The patient's primary problem is used to select a flowchart, which prescribes core modules from the EST for that problem; the therapist may repeat some core modules or add modules from other ESTs depending on the youth's response to treatment, presence of comorbid problems, and emergence of treatment-interfering behaviors. In a RCT testing an earlier version of MATCH (without trauma modules), feedback was obtained via weekly ratings of symptoms and top-priority problems identified by youths and caregivers, and via session-by-session tracking of modules delivered (e.g., psychoeducation, fear ladder), practices employed (e.g., homework assignment, role play), and events (e.g., crisis, family member attendance) occurring during therapy (Chorpita, Bernstein, Daleiden, & The Research Network on Youth Mental Health, 2008; Weisz et al., 2011). MATCH plus feedback outperformed usual care whereas standard ESTs (i.e., three separate single-problem ESTs encompassing MATCH treatment components) plus feedback did not (Weisz et al., 2012). MATCH also significantly outperformed usual care (but not standard ESTs) at two-year follow-up (Chorpita et al., 2013). These findings suggest that modular designs of ESTs may offer incremental benefit over usual care and standard ESTs.

Therapies can be both modular and adapted for specific subgroups. Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism (BIACA), contains CBT modules for youth anxiety, plus modules to build social and daily living skills, suppress restricted interests and repetitive behaviors, and manage behavior, that are employed flexibly to meet individual needs (Sze & Wood, 2007). Moreover, adaptations (e.g., increased parent involvement, visual aids, concrete language) were incorporated to help autistic youths master the material. BIACA has ameliorated anxiety, social communication, and daily living skills compared to waitlist or usual care in several RCTs (Drahota, Wood, Sze, & Van Dyke, 2011; Fujii et al., 2013; Storch et al., 2013; Wood, Drahota, Sze, Har, et al., 2009; Wood, Drahota, Sze, Van Dyke, et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2015).

Sequential, Multiple Assignment, Randomized Trials

A RCT comparing modular therapy to its standard non-modular equivalent evaluates the overall benefit produced by a set of treatment decisions (depicted in flowcharts). In contrast, a sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trial (SMART; Lei et al., 2012) evaluates the specific benefit attributed to each decision, and may be especially useful when insufficient theoretical or empirical justification exists for constructing decision rules. SMART designs separate the treatment regimen into two or more stages. Patients are initially randomized to a particular treatment in the first stage, followed by assessment of treatment response, then possible randomization to one of multiple next-stage treatment options. For example, in one study of ADHD treatments (Lei et al., 2012; Nahum-Shani et al., 2012), youths were first randomized to low-intensity behavioral modification or low-intensity stimulant medication; at the decision point two months later, responders in each condition were assigned to continue with their treatment in the second stage whereas nonresponders in each condition were randomized to a high-intensity version of their first-stage treatment or to a combination of behavior modification and stimulant. This design allowed comparison of the two first-stage treatments, as well as four adaptive interventions. SMARTs can also randomize participants to “time-point/assessment conditions” to determine which of several time-points or assessments would produce the best outcomes when used for decision-making (Gunlicks-Stoessel, Mufson, Westervelt, Almirall & Murphy, 2015). After obtaining evidence that specific decision rules optimize therapeutic gains, the SMART-informed adaptive intervention can be tested in another RCT. A collection of completed or ongoing SMARTs are displayed at http://methodology.psu.edu/ra/smart/projects.

Youth-focused SMARTs have yielded some initial results. One SMART (Kasari et al., 2014) of minimally verbal children with autism found superior outcomes for first-stage treatment with a developmental/behavioral communication intervention augmented by a speech-generating device (vs. non-augmented intervention), and, for nonresponders after three months, second-stage treatment with an intensified version of the augmented intervention (vs. intensified non-augmented intervention). Another SMART (Gunlicks-Stoessel et al., 2015) of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents determined that the four-week time-point for switching treatment strategy due to nonresponse was more feasible, acceptable, and effective than the eight-week time-point.

Measurement Feedback Systems

Adaptive interventions such as MST, MATCH, and those tested in SMARTs require periodic assessments of treatment outcomes and processes throughout episodes of care so that clinicians can obtain feedback about patient progress and make informed treatment decisions. These assessments need to be psychometrically sound, sensitive to clinical change, brief enough for frequent administration, and clinically useful (Hunsley & Mash, 2007; Kelley & Bickman, 2009). Measurement feedback systems (MFS) serve to administer the assessments, then store and display the data in meaningful formats, to convey to therapists and supervisors whether the treatment is working (Bickman, 2008; Chorpita et al., 2008).

One MFS involves administration of the Youth Outcome Questionnaire (Y-OQ; Burlingame et al., 2001, 2005) and Youth Outcome Questionnaire Self-Report (Y-OQ-SR; Ridge, Warren, Burlingame, Wells, & Tumblin, 2009; Wells, Burlingame, & Rose, 2003). Designed to monitor youth treatment progress, these parallel caregiver- and youth-report measures are reliable, well-validated, and sensitive to clinical change. Each 64-item measure generates a total score plus six subscale scores: Intrapersonal Distress, Somatic, Interpersonal Relations, Critical Items, Social Problems, and Behavioral Dysfunction. Shorter 30-item and 12-item versions of the Y-OQ have also been developed (Dunn, Burlingame, Walbridge, Smith, & Crum, 2005; Tzoumas et al., 2007). The Y-OQ and Y-OQ-SR have been used to identify youths at-risk of treatment failure in community mental health and managed care settings (Cannon, Warren, Nelson, & Burlingame, 2010; Warren, Nelson, Burlingame, & Mondragon, 2012). Computer software is available to score the items and generate reports displaying clinically relevant information (e.g., patient distress over time, whether expected progress has been made) immediately after responses are entered (see www.oqmeasures.com). When treatment failure is predicted, decision-making may be facilitated by Youth-Clinical Support Tools (Y-CSTs; Warren & Lambert, 2012), which comprise therapy process measures (e.g., therapeutic relationship, self-efficacy, motivation) designed to pinpoint treatment obstacles and suggestions for resolving each obstacle (Whipple & Lambert, 2011). We are unaware of any published efficacy studies of the Y-OQ/Y-CSTs system, though we note one ongoing RCT of MFSs that incorporate Y-CSTs (van Sonsbeek, Hutschemaekers, Veerman, & Tiemens, 2014). On the other hand, adult versions of the Y-OQ, with or without support tools, have well-documented efficacy, especially among patients at high risk of treatment failure (Shimokawa, Lambert, & Smart, 2010). Additional support for the efficacy of MFSs derives from an RCT assessing a different MFS for youths: providing weekly feedback on treatment outcomes and processes improved outcomes relative to a control procedure providing quarterly feedback; moreover, the frequency with which therapists accessed feedback was positively associated with improvement (Bickman, Kelley, Breda, de Andrade, & Riemer, 2011).

Meta-Analyses Comparing Treatments for Specific Patient Characteristics

Most meta-analyses of psychotherapy outcome studies yield findings that are difficult to translate into clinical decisions. Take for instance the recent meta-analysis (Weisz, Kuppens, et al., 2013) comparing youth ESTs to usual care: larger effects were found among studies conducted within North America, participants not required to meet diagnostic criteria, and youth- and parent-reported outcomes. These treatment moderators do not indicate which treatments work better for patients with specific characteristics. A meta-analytic design well-suited to informing personalized intervention is one involving randomized comparisons of alternative treatment strategies or types among patients who have, or who vary on, a specific characteristic.

One such meta-analysis (Cuijpers et al., 2012) investigated differences in efficacy among psychotherapy, medication, and psychotherapy-medication combination treatment for specific subgroups of depressed adults. It included only RCTs that directly compared at least two of the three treatment types for patient samples characterized by sociodemographic factors, by depression type, by presence and type of comorbidity, or by clinical setting. The authors found sufficient evidence to make preliminary recommendations of matching treatment on the basis of four characteristics—medication for dysthymia, combination treatment for older adults and outpatients, and either psychotherapy or medication for primary care patients (combination treatment was not examined in the last subgroup). Sixteen other characteristics (e.g., chronic depression, poor minority women, comorbid personality disorder) were examined but evidence was deemed insufficient for treatment recommendations.

A group of meta-analyses, published as part of a special issue on tailoring therapy to individuals in the Journal of Clinical Psychology (Norcross, 2011), focused on eight social, personality, or behavioral characteristics of patients. Four characteristics—reactance/resistance, preferences, culture, and religion/spirituality—were judged by expert panels evaluating the meta-analytic evidence to be “demonstrably effective” when used to tailor psychotherapy; two characteristics—stages of change and coping style—were deemed “probably effective;” and two characteristics—expectations and attachment style—were considered “promising” but lacking sufficient evidence (Norcross & Wampold, 2011). Adult and youth studies were included in two meta-analyses on culture (Smith et al., 2011) and on stages of change (Norcross, Krebs, & Prochaska, 2011); the remaining meta-analyses included only adult studies. Some of the meta-analyses employed the design that we consider particularly valuable for informing personalized intervention. For example, one meta-analysis (Beutler, Harwood, Michelson, Song, & Holman, 2011) showed that patients with higher reactance displayed better outcomes when randomly matched to treatments or therapists low in directiveness; the authors thus recommended assessing patient reactance and selecting or modifying therapy to decrease therapist guidance for high-reactance patients. On the other hand, the stages of change meta-analysis (Norcross et al., 2011) included only studies linking pretreatment stage of change to treatment outcome because the authors could not find any controlled trials matching patient stage of change to treatment type. From our perspective, a patient characteristic that robustly predicts outcome is a promising candidate for informing tailoring decisions, but only a treatment strategy or type that outperforms another in RCTs of patients with that characteristic can be considered a personalized intervention with evidentiary support.

Data-Mining Decision Trees

Meta-analyses help identify patient characteristics that predict treatment outcome, but do not help clinicians factor multiple characteristics into clinical decisions. Data mining, an exploratory approach for detecting and interpreting patterns in data, is increasingly used to develop decision trees that account for multiple characteristics. Here, we describe two such approaches.

The Distillation and Matching Model (DMM; Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005) mines RCT data to identify treatments, and elements of those treatments, found to be efficacious for participants with specific characteristics. Similar to meta-analysis, the DMM involves systematically searching the literature for RCTs meeting inclusion criteria and coding the RCTs for putative predictors of outcome (e.g., target problem, demographics, setting). Additionally, treatment elements (e.g., limit setting, parent praise) and evidence of efficacy are coded, then algorithms group the elements into distinct profiles showing the relative frequency of each element among efficacious treatments for particular combinations of characteristics. The DMM has led to a clinical tool constructed from a database of hundreds of youth psychotherapy RCTs—one could enter a particular youth's characteristics (e.g., 12-year-old Asian male with disruptive behavior) and obtain a list of efficacious therapies tested with similar populations; relative frequencies of treatment type, setting, and format; and common elements of the efficacious treatments with their relative frequencies (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2013). This tool, as part of a comprehensive service model, showed medium-to-large pre-post effects in a large-scale implementation study (Southam-Gerow et al., 2013), but, to our knowledge, has not been examined in RCTs.

Classification and Regression Trees (CART) is a tree-building algorithm that relies more heavily on data, and less on researchers’ hypotheses, to illuminate the relationships between several predictors and one outcome (King & Resick, 2014). The algorithm assesses all putative predictors and their possible cutpoints to find one that best splits the sample into two subgroups with maximally homogeneous within-group outcome; the splitting procedure is repeated on the newly-generated subgroups until some specified criterion (e.g., minimum subgroup size) is met. For example, using data from children with autism spectrum disorders receiving social skills interventions, CART was employed to examine peer engagement at pre-intervention and change in engagement by mid-intervention as predictors of post-intervention engagement (Shih, Patterson, & Kasari, 2014). The first best split was a 14% mid-intervention increase in engagement and the second best split was 9% of time engaged at pre-intervention for both subgroups, resulting in four distinct subgroups: low (pre-intervention engagement) and steady (engagement over time), moderate and steady, low and increasing, moderate and increasing. CART could inform the construction of an adaptive intervention (e.g., children predicted to respond poorly could receive another treatment or switch treatments midway), but we are unaware of prospective RCTs testing the efficacy CART-informed youth psychotherapies.

Individualized Metrics

Most treatment research seeks to investigate the relationships among variables in a sample of patients. Unfortunately, common metrics of variable relationships (e.g., effect size, significance level) are of little help to a clinician who needs to identify the treatment likely to be most effective for a particular patient who has several characteristics that may each influence her treatment response. If the patient prefers another treatment, the clinician will need to estimate the difference in benefit between her preferred and optimal treatments to make an informed recommendation. Clinical decision-making can be greatly enhanced with individualized metrics, which quantify the benefit each patient is expected to receive from alternative interventions, given her characteristics.

One such metric is the Personalized Advantage Index (PAI; DeRubeis et al., 2014)—the estimated benefit conferred by a particular person's optimal treatment relative to his non-optimal treatment. Using data from a RCT of CBT vs. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for adults with major depression, the PAI was generated by first identifying pretreatment patient characteristics that predict differential response then using these predictors (life events, medication trial history, comorbid personality disorder, marital status, employment status) to estimate each patient's posttreatment outcomes in both conditions (DeRubeis et al., 2014). The optimal treatment for each patient was determined, and its advantage over the non-optimal treatment was computed. Although CBT and SSRI are considered equally efficacious treatments on average, there was a medium effect for receiving one's optimal treatment vs. one's non-optimal treatment—comparable to effect sizes seen in RCTs comparing active to control treatments (DeRubeis et al., 2014).

Another individualized metric is the probability of treatment benefit (PTB; Lindhiem, Kolko, & Cheng, 2012)—the estimated probability that a particular person would benefit from a treatment given one or more characteristics. The Child/Adolescent Anxiety Multimodal Study dataset was used to create charts showing the posttreatment probabilities of experiencing outcomes in the normal range, and of experiencing improvement, at different levels of pretreatment symptom severity crossed with treatment condition (Beidas et al., 2014). The charts showed that the probabilities of obtaining normal-range outcomes were similar for the three active treatments for youths with mild anxiety (CBT 78%, SSRI 80%, Combination CBT-SSRI 78%), but differed across treatments for youths with severe anxiety (CBT 48%, SSRI 27%, Combination CBT-SSRI 62%).

RCTs will be needed that prospectively match youths to their optimal treatment based on individualized metrics. Evidence that the matching condition outperforms non-matching controls would support the individualized metric-based approach.

Questions for a Science of Personalized Interventions

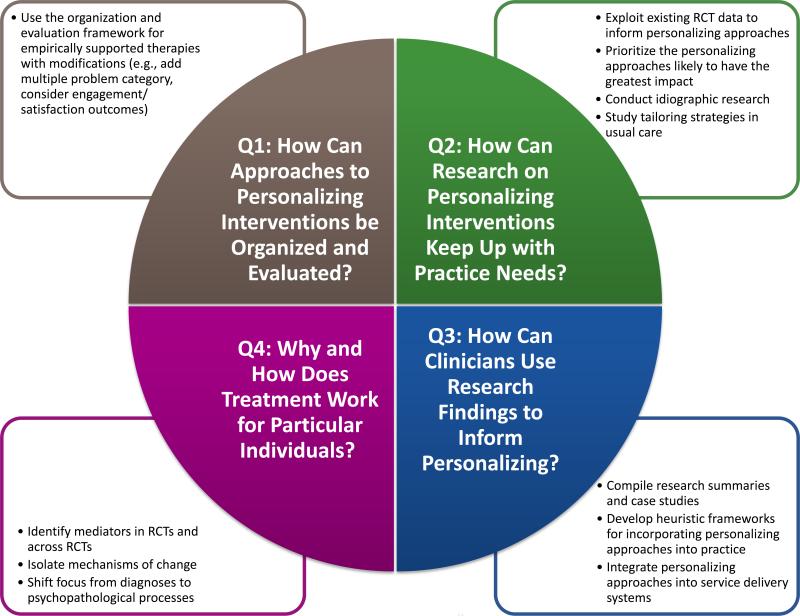

Research efforts to personalize interventions have the potential to markedly improve mental health care, but also present challenging questions. In this section, we note some of these questions and propose ways to address them. Figure 1 summarizes these questions and proposals.

Figure 1.

Questions presented by a science of personalized intervention and proposals to address them. RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Question 1: How Can Approaches to Personalizing Interventions be Organized and Evaluated?

Personalizing approaches include stand-alone protocols (e.g., modular therapies), strategies to be used with a stand-alone treatment (e.g., MFSs), and treatment selection and sequencing tools (e.g., individualized metrics). These disparate forms of personalizing approaches highlight the need for an organizational system and evaluation criteria: What should the basic unit of organization and evaluation be? Does it matter what treatments the personalizing strategies are used with? What is an appropriate control group for tests of personalizing approaches? How should personalizing approaches that are not specific to one problem area, or that encompass multiple problems, be categorized?

Proposal 1: Use the EST organization and evaluation system with modifications

The system employed to organize and evaluate ESTs could be used for personalizing approaches. Designation as an EST (well-established or probably efficacious) requires, among several criteria, at least two RCTs demonstrating that the therapy outperforms waitlist control, at least one RCT demonstrating that the therapy outperforms placebo or another active treatment, or at least one RCT demonstrating that the therapy works as well as another EST (Silverman & Hinshaw, 2008; Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2014). This system is already familiar to many researchers and clinicians, and it rests on the use of experimental designs established for the evaluation of treatment efficacy. The standalone personalized interventions reviewed in the previous section have already been tested in RCTs and can be categorized using EST criteria. The personalizing strategies are either experimentally manipulable or can guide the development or selection of interventions that can be tested in a controlled study. Documenting efficacy against waitlist, placebo, or active treatment control could help establish the personalized intervention as empirically supported; establishing incremental efficacy of personalization would further require the control group to comprise the same intervention either without personalization, or with personalization to yoked participants’ characteristics (for an example, see Schulte et al., 1992). Among the personalized interventions reviewed, it appears that only MATCH and some culturally adapted therapies have established incremental efficacy. Treatments targeting youths’ environments do not have non-personalized versions, but because they have demonstrated efficacy against active controls in numerous RCTs, it makes little sense to create non-personalized versions solely for comparison purposes.

One possible modification is to use a separate label (e.g., efficacious and personalized) for personalized interventions that have demonstrated incremental efficacy. Another modification is the addition of a multiple problem or transdiagnostic category in the organization of personalized interventions. Additionally, beyond symptom severity and functional independence, treatment engagement and satisfaction of youths, caregivers, and clinicians will be meaningful outcomes for evaluating personalized interventions. This is particularly true for interventions developed to boost engagement and satisfaction among families (e.g., culturally adapted therapies) and among clinicians (e.g., modular therapies) to promote treatment participation and sustainability.

Finally, some issues for further research remain. Some personalizing strategies (e.g., MFSs) do not have to be used with specific problems, treatment type, or protocols. Whether efficacy of these strategies depends on the problem or treatment will need to be determined empirically.

Question 2: How Can Research on Personalizing Interventions Keep Up with Practice Needs?

Because establishing evidence-based personalized interventions will require time-consuming prospective controlled studies, which must themselves be informed by prior theory or research, it could take many years for a personalized intervention to achieve evidence-based status. Meanwhile, there is an immediate need to personalize interventions to maximize their effectiveness. If research cannot keep up with practice needs, clinicians may have to tailor treatments for their patients using methods that lack empirical support. Several strategies may help reduce that risk.

Proposal 2a: Exploit existing RCT data to inform personalizing approaches

Although prospective RCTs are required to establish the efficacy of personalized interventions, much of the prior research informing intervention selection and development can be conducted with existing RCT datasets.

Because they involve analyzing existing RCT data, individualized metrics and data-mining decision trees may be the quickest methods for generating evidence to personalize interventions. The DMM already draws on hundreds of youth psychotherapy RCTs to inform the selection of psychotherapy protocols or elements based on patient characteristics; and individualized metrics, if computed for all suitable RCTs of youth psychotherapy, could provide a precise way to match many patients to their optimal treatments. Although some researchers (Beidas et al., 2014) have recommended that the metrics be computed from the exact treatment, setting, and population with whom they are meant to be used, which would maximize precision, many clinicians may find it acceptable and feasible to use metrics generated from an RCT involving participants and settings similar to those in their practice. Data-mining decision trees can also provide empirical support for decision rules to be tested in a SMART or standard RCT of an adaptive intervention, when initial outcomes or processes are assessed as predictors.

Meta-analysis is another method that can capitalize on the extensive RCT data already gathered to accelerate the development of personalized interventions. As discussed earlier, meta-analyses of RCTs directly comparing alternative treatments for patients with specific characteristics have been conducted to guide the personalizing of interventions, but these have focused mainly on adults. More of these meta-analyses are needed to identify youth and family characteristics that can inform the selection of optimal treatments for individuals with those characteristics. Other meta-analytic designs can also inform personalizing. Network meta-analysis (Salanti, Higgins, Ades, & Ioannidis, 2008) integrates findings from indirect and direct comparisons across RCTs with different treatment/control conditions, thus it can assess the comparative efficacy of more treatments types, or more finely differentiated treatments (e.g., different types of therapy and medication), than is possible with a meta-analysis of direct comparisons. A larger sample of RCTs may also be included—an important advantage if the study sample is limited to patients who have, or who vary on, specific characteristics. In addition, individual patient (or participant) data (IPD) meta-analysis (Cooper & Patall, 2009) may reveal treatment moderators that are undetectable in standard meta-analyses using aggregated data. These newer meta-analytic techniques are only beginning to be used with youth psychotherapy RCTs (e.g., Purgato et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2015), but they could become powerful and efficient methods in the armamentarium for advancing personalized intervention science.

Proposal 2b: Prioritize the personalizing approaches likely to have the greatest impact

To make the greatest impact on practice, the most strategic research plan may be to prioritize the development of personalized interventions and strategies that are likely to benefit the most people. MFSs could potentially be used with all clinicians and youths, regardless of target problem, treatment, and setting; consequently, these systems may have the widest reach in clinical practice (Scott & Lewis, 2015). However, they require further research before they are ready for dissemination. The efficacy of the Y-OQ/Y-CST system awaits evaluation in RCTs, and the MFSs used with MST and MATCH have not been adapted for use with different treatments. Personalized interventions targeting multiple problems such as MATCH are also likely to be usable with a greater number of youths. In addition, personalizable psychotherapies that are highly disseminable and implementable are good candidates for adapting to specific subgroups—in fact, this is exactly what the developers of MST, TFCO, and MDFT are doing (see Henggeler & Schaeffer, 2010; Liddle, 2010; Smith & Chamberlain, 2010).

Another way to create a large impact is to prioritize personalized interventions targeting populations whose needs are poorly served by existing ESTs and usual care. For example, researchers (Lau, 2006; Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010) have espoused adapting ESTs for specific cultures only under certain circumstances, such as documented poor treatment engagement or response, or unique symptoms or risk/resilience factors unaddressed by existing ESTs. After all, evidence indicates that ESTs work well for many ethnic minority youths, and adaptations sometimes reduce the efficacy or efficiency of those ESTs (Huey et al., 2014). In addition, we note that some youth ESTs actually perform worse than usual care (Weisz,et al., 2006; Weisz, Kuppens, et al., 2013). There is little reason to expend resources on personalizing an EST that does not work well for a population if usual care or another EST does.

Proposal 2c: Conduct idiographic research

Citing the tremendous investment of time and resources needed to complete RCTs, researchers (e.g., Barlow & Nock, 2009) have argued for conducting more idiographic research to propel psychological science forward.

Among idiographic research designs, the single-case experiment is especially rigorous and suitable for evaluating interventions because it can identify causal relationships between variables that are manipulated over time—instead of across individuals, as in RCTs—and outcomes measured during various phases of the manipulations. Although recent versions of youth EST criteria have prioritized RCTs (Silverman & Hinshaw, 2008; Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2014), the original EST criteria included both RCTs and single-case experiments as acceptable research designs for demonstrating treatment efficacy (Chambless & Hollon, 1998). Acceptable single-case experimental designs include (a) ABAB (i.e., alternating treatment and control conditions over time in one individual), (b) equivalent time samples (i.e., among several individuals, randomly assigning time intervals for each individual to treatment and control conditions), (c) multiple baselines across behaviors (i.e., treating three different behaviors in one individual, one behavior at a time), (d) multiple baselines across settings (i.e., treating the same behavior in one individual in different settings, one setting at a time), and (e) multiple baselines across participants (i.e., treating the same behavior in several individuals, one individual at a time; Chambless & Hollon, 1998). Perhaps the biggest limitation of single-case experiments is that they work only under certain conditions: when effects fade quickly after treatment is stopped and return quickly when treatment is continued, when treatment gains are generally constant over time or stages of treatment, and when gains in one behavior or setting do not automatically transfer to another behavior or setting (Chambless & Hollon, 1998).

When the conditions noted above are absent, other idiographic methods may still be used to help accelerate research on personalizing interventions. Person-specific analyses involve examining relationships among processes within an individual over time (Molenaar & Campbell, 2009). One study applied person-specific factor analyses to the symptoms of 10 individuals with generalized anxiety disorder, self-rated over at least 60 consecutive days; it uncovered between-individual differences not only in the latent factors best representing each individual's syndrome, but also in the correlational and predictive relationships among intraindividual factors (Fisher, 2015). The author argued that such individualized assessment of symptomatology can pave the way for personalizing strategies that select treatment modules and time their delivery according to the individual's latent factors and their interrelationships.

Proposal 2d: Study tailoring strategies in usual care

Meta-analyses of direct comparisons between youth ESTs and usual care (Weisz et al., 2006; Weisz, Kuppens, et al., 2013) have found that most studies reported very little about therapist practices in usual care, even though usual care performed as well as or better than ESTs in some studies. Hence, we have advocated studying usual care with the aims of advancing the implementation of youth ESTs and strengthening youth psychotherapies (Weisz, Ng, & Bearman, 2014; Weisz, Ng, Rutt, Lau, & Masland, 2013).Additionally, studying usual care could serve to document clinicians’ strategies for tailoring therapy to individual youths—a prerequisite to testing these strategies in controlled research. In a qualitative study, practicing psychologists reported selecting treatment strategies, often from different orientations, to fit a particular patient (Stewart, Stirman, & Chambless, 2012). This finding is consistent with another study tracking usual practice of ESTs among clinicians who were trained and supervised on those ESTs as part of a RCT three to five years earlier (Chu et al., 2015). Furthermore, strategies already used by clinicians are quite likely to be implementation-ready. Therefore, gathering “practice-based evidence” (Margison et al., 2000) on how practitioners typically tailor ESTs to individuals may be a productive research direction.

Gathering practice-based evidence on tailoring strategies poses its own challenges. Although clinician-report (Weersing, Weisz, & Donenberg, 2002) and observational coding (McLeod & Weisz, 2010) measures have been developed to document treatment components in youth psychotherapies, including usual care, additional work will be needed to systematically examine how the choice and sequencing of treatment components depends on individual characteristics and treatment progress. To start, one might use existing RCT data to conduct systematic case studies of patient-therapist dyads who were assigned to usual care and achieved favorable outcomes; these successful cases may be compared to cases that experienced treatment failure (see Dattilio, Edwards, & Fishman, 2010). This approach has several advantages: RCTs typically involve rigorous assessments before, during, and after treatment; taped or written records of therapy sessions are often available; and a detailed examination of therapy processes, patient characteristics, and outcome trajectories is more feasible than for the entire group (Dattilio et al., 2010). Tailoring strategies observed to yield favorable outcomes can be tested in prospective controlled research, or compiled and used to develop a standardized coding system.

Question 3: How Can Clinicians Use Research Findings to Inform Personalizing?

Clinicians may quite readily adopt some personalized interventions. For example, clinicians may welcome modular therapies because they offer flexibility that fits with their actual practice or beliefs about competent practice (see Borntrager et al., 2009). On the other hand, disseminating other personalizing approaches such as MFSs may be more challenging (see Boswell, Kraus, Miller, & Lambert, 2015). Either way, dissemination and implementation of personalized interventions are likely to be hampered by financial, logistical, administrative, organizational, and ideological obstacles that often hinder the adoption and sustained use of new practices and systems with fidelity (Gallo & Barlow, 2012; Weisz et al., 2014). Here, we propose three ways to address some obstacles clinicians may face in using research to personalize their practice.

Proposal 3a: Compile research summaries and case studies of personalizing approaches

A crucial early step in the adoption of new interventions is to inform clinicians, supervisors, and administrators about those interventions. Experiments have shown that providing research summaries of efficacious treatments made clinicians more likely to choose those treatments for a case vignette and that including case studies increased clinicians’ interest in receiving training for those treatments (Stewart & Chambless, 2007, 2010). Case studies were also the most highly-valued type of evidence influencing clinicians’ self-reported decisions to adopt an intervention, irrespective of their attitudes towards evidence-based practices (Allen & Armstrong, 2014). Hence, reviews containing research summaries and case studies may serve as helpful resources on personalizing approaches for clinicians.

Reviews compiled as part of a special issue or series may be particularly visible and accessible as current research on personalizing approaches that may ordinarily be published in journals across different subfields would be located in a single issue and cited together in an editorial. For example, to disseminate evidence-based assessment to practice settings, proponents have published a special series (Jensen-Doss, 2015) containing research summaries; case studies; practice recommendations; and a compilation of free, brief, and psychometrically-sound measures in Cognitive and Behavioral Practice as a practical guide for clinicians seeking to use evidence-based approaches to clinical decision-making.

An alternative to publishing information on personalizing interventions in professional journals is to add this information to existing websites for evidence-based psychosocial interventions that are already widely accessed, such as the U.S. National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/) and Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development (http://www.blueprintsprograms.com).

Proposal 3b: Develop heuristic frameworks for incorporating personalizing approaches into practice

After gaining access to information about several personalizing approaches, clinicians seeking to conduct an evidence-based personalized intervention will have some complex decisions to make. They need to choose one or more approaches that fit a particular patient, administer the necessary assessments and interpret the results, integrate the selected approaches with one another or with a standard EST to form a coherent intervention—and then possibly repeat this process at various points throughout treatment. This contrasts sharply with clinicians who choose simply to deliver a standard EST—they only need assess the patient's primary problem and then choose a single protocol for the problem and age range. To assist clinicians in conducting personalized interventions, we recommend the development of heuristic frameworks that incorporate personalizing research into various stages of treatment planning. We have developed a basic heuristic framework, depicted in Figure 2, of the various stages before and during treatment that can be personalized, and the type of research that can inform personalizing at each stage.

Figure 2.

Stages in personalizing interventions and research that can inform each stage. ESTs = empirically supported therapies, MFSs = measurement feedback systems, SMARTs = sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trials.

A more fully detailed example of a heuristic framework is the science-informed case conceptualization (Christon, McLeod, & Jensen-Doss, 2015). The authors provided guidelines for conducting evidence-based assessment and evidence-based treatment that include personalizing approaches such as MFSs and individualized metrics, illustrated with a case study. Because case conceptualization has traditionally been used by clinicians to make decisions about individual patients (Persons, 2013), framing research on personalizing approaches and ESTs as something to be incorporated into usual clinical practice may be perceived more positively than framing research as something that should replace usual practice. This idea is supported by the finding that clinicians are open to adopting ESTs if they can integrate them into their existing treatment framework and practice patterns (Palinkas et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2012).

Proposal 3c: Integrate personalizing approaches into service delivery systems

Many clinicians who must conform to the practice guidelines of their service organization; or who simply lack the necessary time, resources, and familiarity with research to use personalizing approaches on their own. Large-scale adoption of new treatments often requires integrating them into service delivery systems and supporting their use with appropriate training, supervision, materials, and infrastructure (for examples, see McHugh & Barlow, 2010). Consistent with this idea, implementation efforts for personalizing approaches often occur at the level of clinic agencies and government mental health departments. With 425 treatment teams in 32 U.S. states and 10 countries, MST exemplifies a widely disseminated personalized intervention, its success attributed by its developers to several factors: the creation of “purveyor organizations” focused on transporting MST to each setting; the modification of organizational practices and policies to support treatment delivery with integrity; and extensive collaboration with service providers, the juvenile justice system, and funders (Henggeler, 2011; Schoenwald, 2010). In addition, MFSs are increasingly incorporated into mental health services, including those in schools (Borntrager & Lyon, 2015), the U.S. Department of Veteran's Affairs (Landes et al., 2015), and several U.S. states and countries including the United Kingdom, Australia, and Sweden (Bickman, 2008; Holmqvist, Philips, & Barkham, 2015).

Question 4: Why and How Does Treatment Work for Particular Individuals?

Researchers have argued that investigating why and how treatments work is “probably the best short-term and long-term investment for improving clinical practice and patient care” (Kazdin & Nock, 2003, p. 1117). This is because understanding mechanisms of therapeutic change can lead to more effective and efficient treatments, and enrich theories of behavior change and human functioning (Kazdin & Nock, 2003; Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). The literature reviewed in this paper suggests that a particularly challenging variant of this question may be why and how treatments work for particular individuals—but strategies for addressing this question appear rather different from those developed for research on groups. One cluster of personalizing approaches (e.g., therapies adapted for specific subgroups, modular therapies, therapies targeting youths’ environments) assumes that individuals have various constellations of problems, that each problem can be targeted by a treatment or treatment modules, and that optimal treatment targets each individual's constellation of problems. However, the change mechanisms of those ESTs that provide the content for personalized interventions have not been well-studied (Kazdin & Nock, 2003); and we may not even have methods, yet, for studying the change mechanisms of the personalized interventions themselves. We do not know, for example, whether MATCH outperformed standard ESTs because it was better able to address the primary problem, comorbidities, or treatment-interfering behaviors; or because it had greater buy-in from therapists; or because of other reasons. In fact, we lack—and need to develop—sound methods for finding out. Another group of personalizing approaches (e.g., individualized metrics, data-mining decision trees) assumes that individuals who have the same problem may respond differently to different treatments. They can tell us which individuals with which characteristics are likely to respond well to which treatments, but not why. We need to develop methods to answer this pivotal question.

Proposal 4a: Identify mediators within and across RCTs

As a first step toward identifying candidate mechanisms of change, researchers (e.g., Kraemer et al., 2002; Weersing & Weisz, 2002) have advocated studying mediators in the context of RCTs—that is, studying intermediate variables evident during the course of treatment that may statistically account for the treatment-outcome relationship (Kazdin, 2007). Although putative mediators are often measured in RCTs of youth ESTs, published studies of mediation tests are relatively scarce (Weersing & Weisz, 2002; Weisz, Ng, et al., 2013). We encourage researchers to harness this potentially valuable source of untapped data by conducting mediation tests with existing RCT data using more recent approaches that offer distinct advantages over the classic Baron and Kenny (1986) method. These approaches include bias-corrected bootstrapping, joint significance testing, PRODCLIN asymmetric confidence-intervals testing, or causal mediation methods (see Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007; Imai, Keele, & Tingley, 2010; Valeri & Vanderweele, 2013). Particularly relevant to personalized interventions are moderated mediation or conditional indirect effects analyses (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007), because they allow researchers to determine if mediation effects vary by some participant characteristic. The techniques might be used, for example, to determine whether MATCH therapists’ use of treatment modules outside the primary problem area mediate reductions in overall symptoms only for youths with comorbidities.

Systematic and meta-analytic reviews of mediation effects, also rare compared to that of psychotherapy outcomes, could help to identify robust mediators, variables that are most likely not mediators, and variables that have been inadequately tested as mediators. Meta-analyses of mediation relationships involving multiple candidate mediators could be especially valuable as they could generate mean mediation effects for each candidate across studies and allow comparison of their effect sizes. Mediation meta-analyses can be conducted using recently developed statistical techniques such as meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM; e.g., Cheung, 2014). The mediators with the largest effects can then be assessed as candidate change mechanisms in future research, or used to inform the refinement of therapies (e.g., components targeting robust mediators may be retained while removing other components).

Proposal 4b: Isolate mechanisms of change

Multiple criteria must be satisfied to validate a change mechanism: the candidate mechanism must be strongly associated with treatment and with outcome, specific such that other candidates do not mediate outcome, consistent across studies, plausible in the context of the current evidence base, shown to cause the outcome in the expected direction, and change in the candidate must precede change in the outcome (Kazdin, 2007; Kazdin & Nock, 2003). To meet the last two criteria, the candidate mechanism will have to be experimentally manipulated in a RCT or SMART, and both the candidate and outcome will have to be frequently assessed.

Furthermore, causal and temporal relationships among therapist practices, change mechanisms, and outcomes can be bidirectional in psychotherapies, especially those that are adaptive. For example, therapist use of a certain practice may first change a mechanism in the patient, which in turn improves outcome, but improved outcome may cause the therapist to adjust his practices or cause further change in the mechanism (Doss, 2004). The longitudinal and reciprocal nature of the data requires not only frequent assessment, but also advanced statistical methods such as dynamic latent difference score models (Ferrer & McArdle, 2003) or time-series panel analysis (Ramseyer, Kupper, Caspar, Znoj, & Tschacher, 2014) to clarify causal and temporal relationships. Given the time, resources, and complexity involved in establishing change mechanisms, we have suggested that researchers identify robust mediators first before investigating whether they meet change mechanism criteria (Weisz, Ng, et al., 2013). In a similar vein, others have recommended first documenting causal and temporal relationships among therapist practices, change mechanisms, and outcomes within an individual before verifying if those relationships generalize to multiple individuals (Boswell, Anderson, & Barlow, 2014).

Proposal 4c: Shift focus from diagnoses to psychopathological processes

Returning to our initial example of personalized medicine for cancer, the breakthrough was the discovery that the same cancer (i.e., same stage, organ of origin, and cell type) can have different drivers across individuals and conversely, that different cancers can have the same driver; the best treatment was the one that targeted a key cancer driver for that individual. The same may be true for some mental health conditions. A panel of six experts on depression agreed that the diagnostic category of major depressive disorder contained heterogeneous clinical features, which may explain why response rates for the most efficacious depression treatments plateau at roughly 65% in RCTs (Forgeard et al., 2011). The experts supported replacing the existing diagnosis-based taxonomy with a new one based on basic psychopathological processes such as learned helplessness, emotion dysregulation, and cognitive biases, because they map better onto neurocircuitry and are thought to drive the development and maintenance of depression (and of other disorders, in some cases). They argued that examining how response rates of existing treatments relate to these processes and circuits could yield fruitful efforts in selecting and refining treatments to target specific drivers of each individual's psychopathology. One such examination of untreated depressed adults randomly assigned to receive CBT or an SSRI (escitalopram) revealed that those with insula hypometabolism responded better to CBT than to SSRI whereas those with insula hypermetabolism responded better to SSRI than to CBT (McGrath et al., 2013). If replicated, neuroimaging-based diagnostics could potentially be developed to help match depressed patients to CBT or SSRI.

The shift from diagnoses to their underlying processes can be better understood in the context of two major developments in clinical science. First, psychotherapy researchers have identified some psychopathological processes that transcend diagnostic categories, leading to the development of transdiagnostic treatment protocols that can target those processes and treat comorbid diagnoses more efficiently (e.g., Farchione et al., 2012). Much of this work has been conducted with adults, but researchers are starting to study transdiagnostic approaches among youths (see Chu, 2012). Second, the NIMH launched the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project, primarily to spearhead research on neural circuits underlying domains of brain function (e.g., cognition, negative emotion) involved in psychopathology, and on how they relate to individual differences in clinical features, genetics, molecular/cellular characteristics, family/social environment, prognosis, and treatment response (Insel et al., 2010). The RDoC project is intended to stimulate research to support a new process-based taxonomy and to improve diagnostic precision, thereby bringing the subgroup approach of personalized medicine to mental health (Insel & Cuthbert, 2015; NIMH, 2015).

To contribute to the science of personalized intervention, treatment researchers may collaborate with basic psychopathology researchers to incorporate assessments of hypothesized pathological processes and associated neurocircuitry into RCTs, and then examine whether these processes predict, moderate, or mediate treatment response. Especially pertinent to personalized intervention are RCTs demonstrating how a particular process or circuit can predict differential response to alternative efficacious treatments (e.g., McGrath et al., 2013). Such findings appear to be exceedingly rare; the majority involve predicting response to a single treatment (Fu, Steiner, & Costafreda, 2013; Simon & Perlis, 2010). Before embarking on a research program focused on pathological processes and neurocircuitry, researchers would be wise to consider possible challenges (e.g., risk of biological reductionism which limits understanding of psychopathology, psychometric problems of laboratory-based measures) as well as ways to address them (see Franklin, Jamieson, Glenn, & Nock, 2014; Lilienfeld, 2014).

Conclusion

Personalized intervention holds the promise of a future in which clinicians routinely deliver the most efficacious and efficient treatment to every patient given his or her individual characteristics and preferences, and effectively adjusts the treatment over time to optimize the patient's clinical and functional outcomes. For this promise to be realized, clinical scientists must build a new science of personalizing intervention. Building blocks for this science can be found in youth therapies adapted for specific subgroups; therapies created for youth environments; modular protocols that facilitate individualizing; designs such as SMART, used to study stepwise strategies for treatment adjustment based on initial patient response; MFSs, used to guide clinical decision-making throughout episodes of care; meta-analyses comparing treatments for specific patient characteristics; improved methods for mining data to build decision trees; and the development of individualized metrics to identify each patient's optimal treatment. As these building blocks are stacked and ordered, it will become increasingly possible to answer such critical questions as how to organize and evaluate approaches to personalizing interventions, how research can keep pace with practice needs, how clinicians can use research findings to inform personalizing, and why and how treatments work for particular individuals. The scope of this agenda is massive, suggesting a marathon, not a sprint. However, personalized intervention science could markedly alter the nature of mental health care and the benefit provided to youths and their families. This objective certainly warrants the best efforts of our most talented clinical scientists in the years ahead.

Key Points.

Personalized interventions are evidence-based methods of tailoring treatments for individuals to optimize their outcomes.

Personalizing interventions involve selecting psychotherapies, pharmacotherapies, or other treatments; deciding whether and how to combine them, what problems to target first and with what techniques; and continual assessment to inform decision-making—based on each patient's characteristics and progress.

Research on personalizing approaches includes therapies adapted for subgroups, therapies targeting youths’ environments, modular therapies, SMARTs, MFSs, meta-analyses comparing treatments for specific patient characteristics, data-mining decision trees, and individualized metrics.

Advancing personalized intervention science requires addressing the organization and evaluation of personalizing approaches, personalizing research keeping up with practice, clinicians’ use of personalizing research in their practice, and why treatments work for particular individuals.

Acknowledgments