Abstract

Objective

In a randomized controlled trial we studied a Brief Motivational Intervention (BMI) for substance use, examining core psychopathic traits as a moderator of treatment efficacy.

Method

Participants were 105 males and females who were 18 years of age and older and in a pretrial jail diversion program. The sample was approximately 52% black and other minorities and 48% white. Outcome variables at a six-month follow-up were frequency of substance use (assessed with the Timeline Follow-back Interview and objective toxicology screens), substance use consequences (Short Inventory of Problems-Alcohol and Drug Version), and self-reported participation in non-study mental health and/or substance use treatment. Psychopathy was assessed using the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R).

Results

BMI interacted with core psychopathic traits to account for 7% of the variance in substance use at follow-up. Treatment was associated with greater use among individuals with high levels of core psychopathic traits. Toxicology screening results were consistent with self-report data. The treatment and standard care groups did not differ on substance use consequences or non-study treatment participation at follow-up and no moderation was found with these outcomes. An exploratory analysis indicated that low levels of affective traits of psychopathy were associated with benefit from the BMI in terms of decreased substance use.

Discussion

Findings suggest that caution is warranted when applying BMIs among offenders; individuals with high levels of core psychopathic traits may not benefit and may be hindered in recovery. Conversely, they indicate that a low-psychopathy subgroup of offenders benefits from these brief and efficient treatments for substance use.

Public Health Significance

This study of an intervention that is widely used in criminal justice systems provides information regarding for whom the treatment works and for whom it may be unhelpful.

Criminal offenders have considerably higher levels of substance use and substance use disorders than individuals in the general population (Fazel, Baines, & Dole, 2006); approximately 50% of offenders meet criteria for substance use disorder (Karberg & James, 2002). In the United States, approximately 50% of all individuals who are arrested are estimated to have used drugs or alcohol at the time of their offense (Mumola & Karberg, 2006). Studies have shown that without treatment, substance using offenders repeat the same types of behaviors that led to their criminal justice status (Harrison, 2001). In short, substance use is highly prevalent among offenders and is intertwined with criminal behavior, indicating the importance of reducing harmful substance use in offender populations.

There are several evidence-based psychosocial treatments for individuals with drug use disorders, including cognitive-behavioral therapy, 12-step facilitation therapy, contingency management, and motivational interviewing (MI)-based treatments (Dutra, Stathopoulou, Basden, Leyro, Powers, & Otto, 2008). Among these treatments, MI-based interventions stand out for being effective in small doses (e.g., 1–4 sessions; Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003), making them potentially useful therapies within the context of criminal justice systems that require rapid and brief engagement with individuals who otherwise may receive no treatment. Moreover, preliminary findings show that MI-based treatments may be particularly effective with hostile or angry individuals, suggesting they may be indicated for persons in the criminal justice system (Project MATCH, 1997). Brief motivational interventions (BMIs) are MI-based interventions that combine normative-based feedback on substance use with MI’s client-centered principles and more directive behavioral strategies in order to rapidly activate and enhance intrinsic motivation to change (Bernstein, Bernstein, Tassiopoulos, Heeren, Levenson, & Hingson, 2005; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). BMIs have garnered significant empirical support as stand-alone treatments for alcohol use and have received some support in the treatment of other harmful substance use (Burke et al., 2003). BMIs are also sometimes efficacious as preliminary interventions that increase engagement with more intensive substance use treatments (Burke et al., 2003; Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010; Rubak, Sandb k, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005; Vasilaki, Hosier, & Cox, 2006).

The little research on BMIs and substance use among criminal offenders has produced mixed results that are less compelling than what has been found in non-offenders. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT), Ginsburg (2000) found that prison inmates who received a BMI session had an increase in recognition of their drinking as a problem relative to a random-allocation control group (in Mann, Ginsburg, & Weekes, 2002, p. 94). Another RCT found that a treatment program incorporating MI principles resulted in later drinking reductions and less drinking and driving among first-time DWI offenders relative to an incarcerated control group without treatment (Woodall et al., 2007). Notably, in the Woodall et al. study even participants with high levels of antisocial behavior experienced greater improvement than antisocial participants who did not receive treatment. However, there are also reports of negative findings concerning the use of BMI for substance use in offender populations. Carroll et al. (2006) found that a combination of BMI and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for marijuana-using offenders performed worse than contingency management and individual drug counseling for reducing positive urine screens (though BMI/CBT did outperform individual drug counseling alone). Miles, Duthiel, Welsby, and Haider (2007) evaluated a substance abuse treatment program for incarcerated offenders with mental disorders. The intervention consisted of motivational interviewing, followed by education, relapse prevention, and a support group. The BMI did not contribute to abstinence, which was instead predicted by involvement in a community support group. Utter et al. (2014) conducted a single-session randomized controlled trial with first time DWI offenders, examining whether the BMI would decrease self-reported drinking or other drug use treatment engagement after 90 days relative to individuals who did not get the BMI session. Results indicated no benefit of BMI for either outcome.

Despite less compelling empirical results for offenders than for non-offender substance users, BMIs have been widely adopted in the criminal justice system. For example, BMIs and are generally promoted among U.S. probation officers as a treatment for harmful substance use and strides have been made toward putting these potentially useful treatments into wider practice (Walters, Clark, Gingerich, & Meltzer, 2007). Notably, however, recent large-scale clinical trials in primary care settings suggest that BMIs offer no benefit in treating substance use (Roy-Byrne et al., 2014; Saitz et al., 2014), leading some to say we should go “back to the drawing board” (Hingson & Compton, 2014) with BMIs. In the race to apply MI to forensic populations, the popularity of these interventions may have outrun the efficacy data (McMurran, 2009). However, this “one-size-fits-all” approach to substance use treatment research belies the fact that many individual-level moderators of BMI efficacy have not been adequately studied.

In offender populations, psychopathy is a potential individual-level moderator that is important to take into account when evaluating the efficacy of interventions. Variation in BMI efficacy among studies of criminal offenders may be, in part, due to the relative prevalence of psychopathy in a particular sample. Psychopathy is a personality disorder characterized by superficial charm, shallow emotional responsiveness, impulsivity, and marked antisocial behavior (Hare, 2003). Psychopathy is linked to substance abuse and post-treatment relapse (Vaglum, 1998; Walsh, Allen, & Kosson, 2007) and may be associated generally with lack of treatment response (Wong & Hare, 2005). Reviews of the relevant treatment literature have highlighted the paucity of empirical data upon which the latter view rests (Silva, Duggan, & McCarthy, 2004). Indeed, in a prospective study of a large sample of civil psychiatric patients, Skeem, Monahan, & Mulvey (2002) found no evidence that Psychopathy Checklist: Screening Version (PCL:SV) scores moderated the relationship between intensive treatment and later violence. Consistent with this null result, some have suggested that the therapeutic pessimism surrounding psychopathy is more “clinical lore” (Salekin, 2002) or “urban myth” (Wilson & Tamatea, 2013) than reality. In the absence of relevant RCT data, whether, under what conditions, and by what mechanisms psychopathy hinders treatment success among adults is a matter of considerable debate (see Salekin, 2002; Harris & Rice, 2006; Polaschek and Daly, 2013; Reidy, Kearns, & DeGue, 2015, for reviews).

Despite limited data to suggest psychopathy hinders treatment response, the disorder is at least a marker for barriers to successful treatment in correctional settings. Individuals with high levels of psychopathic traits are often narcissistic and fail to appreciate the importance of problems in their lives (Cleckley, 1941; Hare, 2003), in part because their overall emotional experience is quite shallow (Brook, Brieman, & Kosson, 2013; Steuerwald & Kosson, 2000). These characteristics, along with a tendency to blame others for their difficulties (Cleckley, 1941; Hare, 2003), are challenges in therapy that necessitate empirical investigation. It is notable that one prior study found that treatment may have contributed to increased violent recidivism for persons high in psychopathy (Rice, Harris, & Cormier, 1992; though see Skeem, Polaschek, & Manchak, 2009, for a critique of this study). More recently, Olver, Lewis, & Wong (2013) found that, in an intensive violence reduction program for high-risk Canadian offenders, positive therapeutic change predicted a decrease in violent recidivism over a 5-year follow-up period. However, such change correlated negatively with core traits of psychopathy. With regard to substance use, a recent cross-sectional study of European offenders indicated that individuals with high scores on the affective facet of psychopathy (indicating deficient emotionality) were less likely to participate in treatment than those with lower scores, providing empirical backing for the idea that these traits are barriers to treatment (Durbeej, Palmstierna, Berman, Kristiansson, & Gumpert, 2014). The overall picture becomes clearer with regard to barriers to treatment when we also consider the Project MATCH (1997) findings cited earlier. That is, among offenders it may not be that frequency and severity of antisocial behavior are primary barriers to treatment; antisociality is multidetermined and antisocial individuals are heterogeneous (Skeem, Johansson, Andershed, Kerr, & Eno Louden, 2007; Swogger & Kosson, 2007). Rather, core traits of psychopathy may be a significant barrier to successful treatment. We believe that, in intervention studies of offenders, psychopathy is important to take into account in a sophisticated fashion, not only to provide important information regarding the treatment of individuals high in psychopathy, but potentially to indicate the true treatment effects for individuals low in psychopathy.

The most often-used measure of psychopathy among offenders is the Psychopathy Checklist - Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 2003). The PCL-R is a valid measure based on interview and file review data. Factor analytic studies of the PCL-R yield two distinct dimensions: Factor 1 (F1) captures interpersonal and affective (sometimes called core) psychopathic traits, and Factor 2 (F2) captures impulsive lifestyle and antisocial deviance (Hare, 2003). For fine-grained analyses, these factors can be further subdivided into correlated lower order dimensions. Factor 1 can be parsed into arrogant and deceitful interpersonal style (interpersonal facet) and deficient emotional experience (affective facet), and F2 can be divided into impulsive, irresponsible lifestyle (lifestyle facet) and frequent and varied antisocial behavior (antisocial facet; Hare, 2003).

In the present RCT, we studied the efficacy of BMI in addition to standard care (BMI+SC) versus Standard Care alone (SC) for reducing substance use and substance use consequences among individuals in a pretrial jail diversion program. We assessed traits of psychopathy as potential moderators and made the following hypotheses: 1) Individuals randomized to BMI+SC would report more days abstinent for all substances at a six-month follow-up session than those randomized to SC, 2) People in the BMI+SC group would report fewer substance use consequences at six months than those in SC, 3) People in the BMI group would become involved in non-study treatments during the follow-up period at higher rates than those in SC group, and 4) The hypothesized main effects (i.e., more days abstinent, fewer substance use consequences, higher non-study treatment involvement) would be moderated by F1 psychopathic traits, such that individuals high in these traits would derive less benefit from the treatment than those low in F1 traits. We made no hypotheses about F2, but examined it in exploratory analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants were 105 adults (68 men and 37 women) in an urban pretrial jail diversion program in upstate New York recruited between 2009 and 2014 subsequent to being charged with a crime. Table 1 describes the sample.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations for study measures at baseline revealed no differences between treatment and control participants (all ps > .05; n = 105).

| Full Sample | BMI+SC | SC | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| N | 105 | 53 | 52 |

| % Male | 64.8 | 56.6 | 73.1 |

| % White | 47.6 | 45.3 | 50.0 |

| % Black | 42.9 | 39.6 | 46.2 |

| % Other race | 9.5 | 15.1 | 3.8 |

| % Unemployed (non-student) | 76.2 | 76.2 | 76.2 |

| Age (M, SD) | 33.4 (10.9) | 33.1 (10.0) | 33.8 (11.8) |

| Highest Grade Completed (M, SD) | 11.8 (1.7) | 11.9 (1.8) | 11.7 (1.5) |

| Percent Days Abstinent (M, SD) | 24.7 (32.5) | 25.8 (35.5) | 23.6 (29.4) |

| AUDIT (M, SD) | 13.0 (11.3) | 13.5 (9.8) | 14.5 (12.8) |

| DAST (M, SD) | 6.4 (2.1) | 6.2 (2.0) | 6.7 (2.2) |

| MDD (M, SD) | 7.8 (4.6) | 7.8 (5.2) | 7.8 (4.6) |

| GAD (M, SD) | 5.2 (3.7) | 5.4 (3.5) | 5.0 (3.5) |

| PTSD (M, SD) | 5.2 (5.9) | 4.8 (5.7) | 5.5 (6.0) |

| Panic (M, SD) | 2.7 (2.8) | 2.8 (2.9) | 2.5 (2.8) |

| Frequency of Alcohol Use (M, SD) | 3.8 (1.7) | 4.0 (1.7) | 3.6 (1.8) |

| Frequency of Cannabis Use (M, SD) | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.0 (2.2) | 3.9 (1.9) |

| Frequency of Cocaine Use (M, SD) | 3.2 (2.1) | 3.1 (2.1) | 3.4 (2.1) |

| Frequency of Opiate Use (M, SD) | 2.7 (1.9) | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.4 (2.1) |

| Frequency of Tranquilizer Use (M, SD) | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.4 (1.0) |

| Frequency of Amphetamine Use (M, SD) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| PCL-R Factor 1 (M, SD) | 8.6 (4.3) | 8.1 (4.3) | 9.0 (4.4) |

| PCL-R Factor 2 (M, SD) | 11.0 (3.6) | 10.6 (3.4) | 11.3 (3.9) |

| PCL-R Total (M, SD) | 21.9 (8.4) | 21.1 (8.2) | 22.9 (8.7) |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; DAST = Drug Abuse Screening Test; Scores for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Panic Disorder (Panic) represent number of symptoms endorsed. PCL-R = Psychopathy Checklist-Revised.

Procedures

Individuals were presented with an announcement about the study in the waiting room of the program and those who indicated an interest in learning more about participation met one-on-one with a member of the research team who described the study in detail. Volunteers who provided informed consent (n = 569; see consort diagram, Figure 1) answered demographic questions, completed several self-report measures, and were compensated with $5 for their time. Based on the data provided, individuals who met inclusion criteria (n = 155) were scheduled for a baseline assessment. Those who attended (n = 105) were enrolled in the study. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were designed to enroll individuals with a wide range of harmful drug use patterns. Inclusion criteria consisted of the following:

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram.

The use of opiate(s) or cocaine once per week or more during the past 6 months, or

Use of another illicit substance (e.g., cannabis) once per week or more during the past six months and a score ≥ 3 on the 10-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Cocco & Carey, 1998). Exclusion criteria were obvious psychotic symptoms or cognitive difficulties that would compromise understanding of the study, as assessed during the informed consent procedure. No interested individuals were excluded based on these criteria.

Those who attended their baseline appointment (n = 105) were enrolled in the study and completed a thorough psychosocial interview and additional assessment measures, provided detailed data to relocate them (e.g., email address), and signed releases so that they could be contacted by phone, mail, or e-mail, and could be met with in county jail should they be charged with a new crime during follow-up. Participants were randomly assigned to BMI+SC or SC based on a random number generator. This study was conducted with the approval of the local Research Subjects Review board and a Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained and maintained throughout the study. Participants were reminded at each session that substance use data would be kept confidential.

Intervention and Control Conditions

During the first year of the study, the psychosocial intervention consisted of three sessions of individual BMI based upon a detailed manual provided by Bernstein et al. (2005). When funding became available in the second year of the study, an additional session was added, for a maximum of four sessions. Over the course of the study, individuals in the intervention condition averaged 2.5 (SD= 1.1) sessions. Sessions that were missed were rescheduled and all BMI sessions were completed within three months after baseline assessment. Treatment dose (i.e., number of sessions) was positively related to F1 traits (r = .33, p <.05) indicating that persons high in F1 missed fewer within study treatment sessions than those without these traits. Dose was unrelated to F2 (r = .14, p = .40). BMIs were delivered by two different doctoral-level therapists with training in MI. Each intervention condition participant met with the same therapist for each session. Initial sessions were approximately 40 minutes in duration (Mean = 40.9 minutes, SD = 7.9) and consisted of the following components, all of which were delivered according to principles of Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) in order to enhance motivation to change substance use:

The therapist worked to rapidly establish rapport and participants were told at the outset that that we were interested in hearing their stories rather than making judgments about their behavior.

With their permission, we encouraged participants to explore the pros and cons of use of each substance assessed positive at baseline.

Based on baseline data we provided feedback on how their rates of illicit substance use compared to the general USA population and discussed screening data on endorsed substance use consequences and mental health issues, encouraging participants to explore links between mental health symptoms and substance use.

We assessed and enhanced readiness to change using the “readiness ruler” (Hesse, 2006) and discussed, when possible, prior instances of valued change and the methods that the participants had used in the past to change.

Participants who were interested in making changes to their substance use were asked if they would like to complete an “action plan” (e.g., what changes they want to make, steps they plan to take, things that could interfere, etc.).

Participants who were interested were given an intake number for a hospital-based, outpatient substance use treatment program, a list of local Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous meetings, and/or an intake number for mental health services. Individuals with mental health problems who indicated interest were given an intake number for general mental health services. For individuals who consented, treatment sessions were audiotaped for later MI fidelity assessment. Three “booster” sessions, at two, four, and six-weeks after the baseline interview followed. These sessions were briefer (Mean duration = 30.0 minutes, SD = 6.4) and were also conducted according to MI principles. These sessions were designed to be responsive to individuals’ needs and motivation. Booster sessions incorporated elements of the first session and/or exploration of participant-defined successes or failures with regard to goals since the previous session.

Therapist fidelity to principles of MI were assessed using the MI treatment integrity coding system (MITI 3.0; Moyers, Martin, Manuel, & Miller, n.d.), a valid tool for this purpose (Forsberg, Berman, Kallmen, Hermansson, Helgason, 2008). A trained research assistant who was not involved in delivering the interventions coded a random selection of audio recordings (n = 20) for adherence to MI. Coding used global indices to assess adherence to MI principles. Possible ratings on indices ranged from 1 (low) to 5 (high). Study therapists maintained adequate adherence to MI across the five domains assessed (evocation = 4.7, SD = .5; collaboration = 4.5, SD = .6; autonomy support = 4.6, SD = .6; direction = 4.7, SD = .5; empathy = 4.5, SD = .5).

To control for assessment reactivity (Maisto, Clifford, & Davis, 2007), each individual in the SC condition met with study personnel at two, four, and six weeks, as well as at six months for substance use assessment. Consistent with the intervention condition, each follow-up session was conducted by the same research team member who conducted the first session and, as with the intervention group, individuals in the control condition were free to participate in non-study treatments. Individuals in the SC group were also given phone numbers for potentially relevant treatment providers after the baseline assessment. All participants were compensated with $50 for assessment time after each non-screening session.

OUTCOME MEASURES

Daily Substance Use (Self-Report)

The Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB; Sobell and Sobell, 1996) was used to gather daily substance use data at baseline and during follow-up. The TLFB interview uses a calendar that serves as a cue for participants to recall daily drinking and drug use. At six months after baseline, participants viewed calendars representing the previous 90 days. We chose this time period because all BMI sessions were completed within the first three months; thus brief and transitory effects of the intervention would not impact the data. During the interview, assessors highlighted major holidays over the three-month period, and then asked the participant to identify personal days of importance. They also prompted recall by identifying extended abstinent periods and recording regular patterns around weekends or pretrial appointment days. Time in controlled environments, including incarceration and inpatient treatment, was recorded. Scores at follow-up were used for individuals who had at least one month out of a controlled environment (of the three months assessed), and yielded percent days abstinent (PDA) for all substances.

Substance Use (Objective Measures)

Starting in the second year of the study, objective measures of substance use were administered at baseline and follow-up sessions to a continuous subset of participants. These measures included a breathalyzer for recent alcohol consumption and a urine screen for THC, opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines. Drug testing was conducted using Testcup Pro 5 urine screens (Varian, Inc.). Results were considered positive if one or more of the listed substances was detected at follow-up, unless the participant indicated that he or she had a prescription and was taking medication as prescribed. This study was conducted in a state that did not permit prescriptions for marijuana at the time of the study.

Substance Use Consequences (Self-Report)

The Short Inventory of Problems - Alcohol and drug version (SIP-AD) was administered at baseline and follow-up sessions. SIP-AD is a 15-item measure designed to assess the frequency of negative consequences of substance use during the past 90 days and measures consequences across health, safety, financial, social, and psychological domains. The SIP-AD is a shortened version of Tonigan and Miller’s (2002) Inventory of Drug Use Consequences (INDUC-2R) and has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Blanchard, Morganstern, Morgan, Lobouvie, & Bux, 2003.)

SCREENING AND BASELINE MEASURES

Demographics

Participants reported employment status, age, race, and education (years completed) during baseline assessments. As most participants (90.5%) were Black or White, a categorical Black/White/Other variable was used to represent race/ethnicity.

Drug Use Screening: Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)

The DAST (Cocco & Carey, 1998), a reliable and valid 10-item estimate of harmful substance use (see Yudko, Lozhkina, & Fouts, 2007, for a review) was used to estimate severity of drug use disorder. Scores range from 0 to 10.

Alcohol Use Screening: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

The 10-item AUDIT (Babor, La Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1992) is a valid tool for screening for harmful alcohol use (Dybek et al., 2006; Knight, Sherritt, Harris, Gates, & Chang, 2003). Scores range from 0 to 40.

Substance Use Frequency for Specific Substances

Using a list of drugs, participants reported their frequency of use for several classes of drugs on a 6-point scale from “never” to “(nearly) every day” and with primary substance of use (Conner, Swogger, & Houston, 2009). The most common primary substance was cannabis (41.0%), followed by cocaine/crack (25.7%), alcohol (16.2%), heroin/other opiates (15.2%), and tranquilizers (1.9%).

Psychopathy

The Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 2003) was completed based upon information from an extensive psychosocial interview, file review, and review of the criminal history database. Extensive research attests to the reliability and validity of this measure (Hare, 2003). One rater scored all PCL-R interviews. A second rater was present for four of the PCL-R interviews and scored an additional eight interviews based on an audio recording. Based on Landis and Koch’s (1977) guidelines, interrater reliability was “excellent” for PCL-R total (intraclass r = .91), F1 (intraclass r = .88) and F2 (intraclass r =.88) scores. As shown in Table 1, mean PCL-R total scores (21.94, SD = 8.43) were similar to those of other offender samples (Hare, 2003). Mean scores for males (M = 24.28, SD = 8.48) were higher than those for females (M = 17.65, SD = 6.51; t = 4.46, p < .01).

Axis I Psychiatric Disorders

Five Axis I conditions were measured using subscales of the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ; Zimmerman & Mattia, 2001a). The PDSQ consists of yes/no questions designed to assess current and recent symptoms of DSM-IV Axis I disorders and has been validated in large-scale studies using structured clinical interviews (Zimmerman & Chelminski, 2006; Zimmerman & Mattia, 2001b; Zimmerman & Sheeran, 2003; Sheeran & Zimmerman, 2004). For major depressive disorder, panic disorder, psychosis, and PTSD, the items assessed symptoms occurring within the past two weeks. For GAD, the time frame was six months prior to assessment. There is evidence that common behavioral disorders represent extremes of continuous dimensions (Plomin, Owen, & McGuffin, 1994). For this reason we created a continuous variable for each disorder by summing the total items endorsed, following Lesser et al.’s (2005) approach. Internal consistency for the five subscales used in the current study was adequate (α = .75–.89). As shown in Table 1, the sample showed significant levels of psychiatric symptomatology across PDSQ scales.

Non-study Treatment

Economic Form-90 (Miller & Del Boca, 1994) was used to assess involvement in non-study treatments. Based on results, a binary variable was created, and individuals were considered to have participated in non-study treatments if they had any non-emergency, non-study intervention for substance use or mental health problems between the baseline and the six-month follow-up sessions.

ANALYSIS

Data were examined for non-normal distributions, outliers, and multicollinearity. Skewed scores on percent days abstinent were improved with a square root transformation; because results were the same with transformed and untransformed versions, we report analyses using the untransformed variable. Individuals with missing data (due to incarceration, time in other controlled environments, or loss to follow-up) were excluded from analysis. At baseline, there were no differences between treatment and control groups (Table 1); thus we used no covariates in the primary analysis. To search for selective attrition, we compared individuals who were included versus individuals who were excluded from analysis on all baseline variables shown in Table 1. Individuals who remained in the study and whose data were analyzed differed from excluded individuals on only one of 21 variables examined; included individuals had a higher frequency of tranquilizer use (F = 7.4, p <.01) than those lost to follow-up. Among predictors there were no outliers (± 3 SDs from the mean), and there was no problematic multicollinearity (rs < .42). Because we had one time point for the criterion variables, we used multiple regression for the primary analyses. These were intent-to-treat comparisons of BMI+SC versus SC for PDA and substance use consequences at six months. In the primary analysis, we examined F1 as a moderator of treatment response. On Step 1 we entered treatment condition (BMI+SC vs. SC); on Step 2 we entered F1; on Step 3 we entered the centered interaction term (condition X F1). Significant interactions were probed using simple slopes analyses (Aiken & West, 1991). The primary analysis was then repeated, replacing F1 with F2 as a predictor to check for moderation. These processes were repeated, replacing PDA with substance use consequences, and then with non-study treatment participation as the criterion in logistic regressions. Reliability analyses were conducted to examine results after controlling for additional covariates and incorporating objective drug screen data. We then conducted exploratory analyses examining interpersonal and affective facets of F1 separately as moderators of treatment efficacy.

Results

Of the 105 participants, 78 (74.3%) were retained through the six-month follow-up session. Of those individuals, five were incarcerated or in other controlled environments for at least the previous 90 days, thus the TLFB yielded no data. Among the 73 (i.e., 36 treatment, 37 control), individuals for whom data were available at six months, results indicated considerable improvement over baseline PDA; from M= 24.7, SD= 32.5 at baseline to M= 51.1, SD = 39.8 at the six-month follow-up. Fifty-two individuals (66.7%) reported participating in non-study treatments during the course of the study, including outpatient drug and alcohol counseling and/or mental health counseling and medical consultation. The BMI+SC and SC groups did not differ on non-study treatment participation (26 per condition). Bivariate relationships between study variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among variables used in multivariate analyses (n = 73).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Female Sex | - | −.03 | .06 | −11 | .27* | −.53** | −.34** | −48** | −48** | .21 |

| 2. Baseline PDA | - | - | .31** | −01 | −08 | −09 | −12 | −.03 | −19 | .02 |

| 3. Follow-up PDA | - | - | - | −.36** | .12 | −.16 | −.32** | −.02 | −.27* | −.10 |

| 4. Follow-up Consequences | - | - | - | - | −.22 | .23 | .36** | .23 | .19 | −14 |

| 5. Non-study Treatment | - | - | - | - | - | −.33** | −.19 | −.36** | −.24* | .02 |

| 6. PCL-R F1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | .62** | .92** | .92** | −.10 |

| 7. PCL-R F2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .50** | .64** | −09 |

| 8. PCL-R Interpersonal | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .69** | −.19 |

| 9. PCL-R Affective | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −.01 |

| 10. BMI+SC Condition | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Note. Pearson’s r used for continuous variables and point-biserial correlations used for dichotomous variables. PDA = Percent Days Abstinent. Follow-up Consequences = substance use consequences (SIP-AD). Non-study Treatment = non-study treatment participation during 6-month follow-up, dichotomous. PCL-R = Psychopathy Checklist-Revised Factors One and Two and the interpersonal and affective facets. BMI+SC = Brief Motivational Intervention plus Standard Care vs. SC condition.

p < .05.

p < .01.

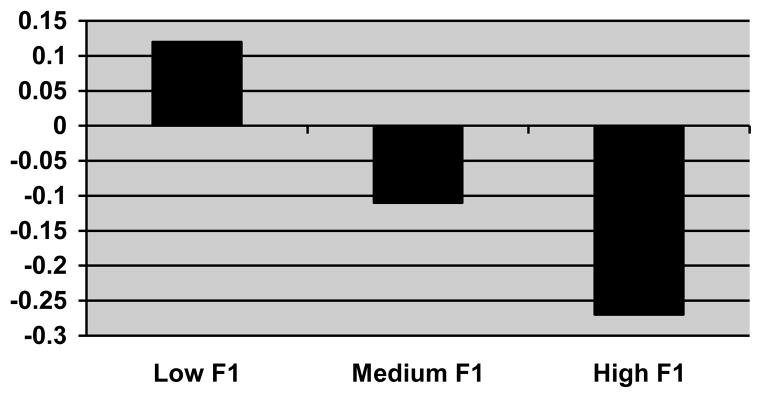

Primary Analysis

The results for a multiple regression testing psychopathy F1 as a moderator of the relationship between study condition and PDA at 6-months are shown in Table 3. Study condition was entered on Step One, and Psychopathy F1 on Step Two. There was no main effect for either of these variables. The grand-mean centered F1 X study condition interaction term, entered on Step Three, was statistically significant (change F = 5.45, change R2 = .07, p < .05). We followed the significant interaction with a simple slopes analysis (Aiken & West, 1991), which indicated the relationship of treatment condition to percent days abstinent at low, medium, and high levels of F1. At low (r = .12, p = .32) and medium (r = −.11, p = .36) levels of F1 traits, the relationship was not significant. However, at high F1 the treatment condition was related to lower PDA (r = −.27, p <.05), indicating more frequent substance use (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Multiple regressions examining the prediction of Percent Days Abstinent (criterion) by BMI+SC, F1 traits, and the BMI+SC X F1 interaction (n = 73).

| Variable | β | t | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step One | BMI+SC | −.10 | −.88 | .01 |

| Step Two | BMI+SC | −.12 | −1.03 | .01 |

| F1 | −.17 | −1.44 | .03 | |

| Step Three | BMI+SC | .44 | 1.65 | .04 |

| F1 | .11 | .64 | <.01 | |

| BMI+SC X F1 | −.65* | −2.33* | .07* | |

| Model R2 = .11* | ||||

Note. BMI+SC = Brief Motivational Intervention plus Standard Care vs. SC condition. F1 = Psychopathy Checklist-Revised Factor One score. BMI+SC X F1 is a centered interaction term.

p < .05

Figure 2.

Relationship (r) of BMI+SC to Percent Days Abstinent at low, medium and high levels of F1 traits.

The same process was repeated, replacing PDA with SIP-AD scores as the criterion variable. In the first regression, none of the predictors (study condition, F1, or the F1 X condition interaction term) approached significance (R2s < .01, ps > .14). In the second regression, F2 remained predictive of substance use consequences after controlling for study condition (R2 = .10, p < .01). Psychopathy F2 did not moderate the study condition - SIP-AD relationship.

Objective Analysis

Objective urine toxicology screens were used starting in the second year of the study and were thus available for a continuous subset (n = 48) of the retained (n = 73) participants with data on the TLFB. We conducted the primary analysis again, replacing TLFB-assessed percent days abstinent with binary (positive, negative) assessments of drug use via urine toxicology results. We found the same interaction: F1 X BMI+SC; change in R2 = .12, p = .06.

Reliability Analyses

First, because male sex was highly related to psychopathy scores, the primary analysis was repeated with sex added as an additional covariate on Step One. The pattern of findings did not change, including the F1 X BMI+SC interaction (change in R2 = .07, p < .05). Second, because F1 was inversely related to treatment participation during follow-up, we conducted the primary analysis again, adding treatment participation outside the study as a covariate to see whether less non-study treatment participation among individuals high in F1 traits accounted, in part, for the results. The F1 X study condition interaction remained statistically significant after controlling for participation in non-study treatments (R2 = .09, p = .01). To ensure that the F1 X BMI+SC interaction truly measured change in PDA, we conducted an analysis controlling for baseline PDA. With baseline PDA as a covariate the F1 X BMI+SC interaction remained significant (change in R2 = .06, p < .05). Finally, we added two additional covariates to this analysis - PCL-R F2 and race/ethnicity - to examine results after controlling for antisocial lifestyle (F2) and the racial makeup of our sample (Table 4). Race/ethnicity accounted for 7% of PDA at follow-up (p <.01) after controlling for F2, treatment condition, and baseline PDA, with Black and Other minority participants having fewer abstinent days than Whites. The F1 X treatment interaction remained significant. There was no F2 X treatment interaction. In summary, reliability analyses suggest that primary findings are robust.

Table 4.

Multiple regression examining the prediction of Percent Days Abstinent (criterion) by the BMI+SC X F1 and BMI+SC X F2 interactions after controlling for baseline Percent Days Abstinent and race/ethnicity (n = 73).

| Variable | β | t | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step One | Baseline PDA | .23* | 2.17* | .06* |

| F2 | −.17 | −1.51 | .03 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | −.29* | −2.46* | .08* | |

| Step Two | Baseline PDA | .24* | 2.20* | .06* |

| F2 | −.19 | −1.62 | .04 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | −.27* | −2.25* | .07* | |

| BMI+SC | −.10 | −.88 | .01 | |

| Step Two | Baseline PDA | .24* | 2.20* | .06* |

| F2 | −.24 | −1.68 | .04 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | −.27* | −2.28* | .07* | |

| BMI+SC | −.09 | − .83 | .01 | |

| F1 | .08 | .61 | .01 | |

| Step Four | Baseline PDA | .23* | 2.21* | .06* |

| F2 | −.35 | −1.94 | .05 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | −.24 | −1.97 | .05 | |

| BMI+SC | .06 | .17 | <.01 | |

| F1 | .34 | 1.85 | .05 | |

| BMI+SC X F1 | −.67* | −2.02* | .05* | |

| BMI+SC X F2 | .44 | .94 | .01 | |

| Model R2 = .05 | ||||

Note. Baseline PDA = percent days abstinent during the three months prior to baseline interview. Race/Ethnicity = categorical Black/White/Other variable. BMI+SC = Brief Motivational Intervention plus Standard Care vs. SC condition. F1 = Psychopathy Checklist-Revised Factor One score. F2 = Psychopathy Checklist-Revised Factor Two score. BMI+SC X F1 and BMI+SC X F2 are centered interaction terms.

p < .05.

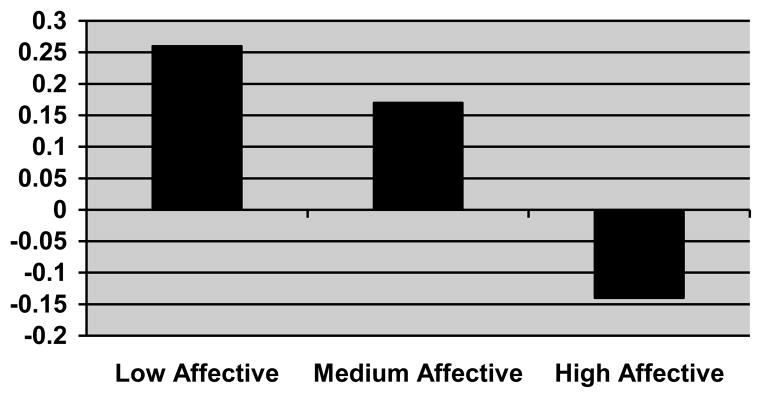

Exploratory Analyses

Because we found a F1 X treatment condition interaction, we were interested in understanding which traits included in F1 (interpersonal, affective, or both) were driving the interaction. Using the Four-Factor model of psychopathy (Hare, 2003), we split F1 into its interpersonal and affective facets. We then submitted each of these facets to a regression similar to the primary analysis. Although the Interpersonal facet was neither related to PDA (change R2 <.01, p = .83) nor interacted with treatment condition (change R2 = .03, p = .14), the Affective facet exhibited an interaction with condition similar to that found in the primary analysis (change F = 9.33, change R2 = .13, p < .01). A simple slopes analysis designed to examine the relationship of treatment condition to PDA at different levels of affective traits of psychopathy indicated a positive treatment effect for individuals in the low affective factor score group based on PDA outcomes (r = .26, p <.05), while there was no relationship between treatment and PDA at medium (r = .17, p =.16) and high levels of affective traits (r = −.14, p = .25). This finding is represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Relationship (r) of BMI+SC to Percent Days Abstinent at low, medium and high levels of affective Traits of psychopathy.

Discussion

In this RCT we examined the efficacy of a BMI+SC versus SC for individuals with harmful substance use in a pretrial jail diversion program. Our hypothesis that core psychopathic traits would moderate outcomes was corroborated with regard to substance use frequency during follow-up, albeit in an unexpected way. The combination of high psychopathy F1 traits and treatment participation predicted more frequent substance use at follow-up, suggesting that adding a BMI to SC may have hindered recovery for high F1 individuals. Our hypotheses that the treatment would help individuals low in F1 traits to decrease substance use consequences and engage in non-study treatments were not corroborated. However, an exploratory analysis revealed that, among people with low affective traits of psychopathy (i.e., who have sufficient emotional range), BMI+SC did indeed result in decreased substance use frequency during follow-up.

Our primary results constitute the first evidence from a RCT that F1 psychopathic traits are associated with reduced efficacy for a substance use treatment. We examined three potential reasons for this finding and none is likely to account for our results. The first was that people high in F1 were less likely to get a good “dose” of treatment in the study. However, F1 was positively related to number of BMI+SC sessions attended. A second potential explanation for primary findings was that people high in F1 were less likely to participate in additional, more intensive treatment following BMI+SC, leading to hindered recovery. Consistent with recent findings (Durbeej et al., 2014), we found that F1 traits predicted less participation in treatments outside the study. However, when extra-study treatment participation was entered as a covariate the results remained the same, indicating that this factor alone did not account for higher substance use levels. Finally, we considered the possibility that individuals high in F1 were more likely to report substance use than people low in F1, who might have higher levels of shame or concern about telling study personnel. This explanation for the results also is unlikely, because objective toxicology screens were consistent with the self-report findings. We are left with preliminary evidence that the treatment did not help - and may have hindered - recovery among substance users high in F1 traits.

Often discussions of substance use among individuals with harmful use elicit at least some resistance (Newman, 1994), and thus MI-based interventions are specifically designed to minimize and “roll with” resistance. BMIs (as opposed to more confrontational therapies) may work particularly well to minimize resistance as a barrier to recovery by using therapist skills, including accurate empathy (Miller, 2002), to increase client engagement (i.e., cooperation, disclosure, and expression of emotion; Moyers, Miller, & Hendrickson, 2005). As noted by Durbeej et al. (2014; see also Miller & Rose, 2009), two active components may underlie the effectiveness of MI-based treatments: 1) a relational component focused on empathy and the “interpersonal spirit” of the treatment and, 2) a technical component that involves eliciting and differentially reinforcing change talk. Perhaps individuals who are high on F1 traits are unable to benefit from the relational component due to their aggressive and manipulative interpersonal styles, weak relational bonds with others, and minimal emotional reaction to material raised in BMI sessions. If this is so, then resistance to change may be elicited and inadequately dealt with, leaving the individual disengaged from therapeutic aspects of the intervention. For an individual with limited emotionality, the “deepest” feelings elicited in these sessions may be a longing for the substance(s) being discussed. Indeed, many of the reasons for discontinuing substance use that BMI often highlights for participants (e.g., sense of fulfillment through work, stronger relationships, less guilt) may not strongly apply to individuals with high levels of F1 traits. With resistance elicited, with minimal connection to the treatment provider, with insufficient reasons to change, the high F1 client may spend a period of time exposed to drug use cues, thus increasing the likelihood of harmful use (Lubman, Kettle, Scaffidi, Mackenzie, Simmond, & Allen, 2009). Moreover, “change talk” followed by failure to change is a defining feature of psychopathy (Cleckley, 1941). Thus, reinforcing change talk, which is generally linked to positive outcomes (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003; Miller & Rollnick, 2004), may have no effect beyond the BMI session for these individuals.

Further examination of psychopathy enabled us to identify individuals for whom the intervention may facilitate recovery. People who are particularly low in affective traits of psychopathy have a sense of personal responsibility for their actions, the capacity to feel guilt and other deep emotions, and the ability to empathize with others. For these people, the relational aspects of the BMI may have been sufficient to minimize resistance and elicit ideas about change that remained with the individual beyond the intervention session in order to build behavioral momentum toward change. While the intervention may have been too low of a dose for the majority of offenders in a sample with severe barriers to change (e.g., low socioeconomic status, criminal justice status, high stress, low education), it may have been a sufficient dose for individuals with low affective factor scores. This exploratory result suggests that, for offenders with sufficient emotional range, a low-dose BMI is helpful despite the presence of other barriers to change. Because resources allocated for treating offenders are chronically scarce, this finding is significant. Whereas we had hypothesized that low F1 scores would indicate treatment amenability, we found that this is only true for individuals low in affective traits of psychopathy. Replication in a larger sample may indicate a class of offenders for whom relatively low-dose BMIs are particularly helpful in reducing substance use.

Contrary to our hypothesis, the intervention did not increase participation in non-study treatments for substance use or mental health. It is possible that barriers to treatment participation, including child and elder care responsibilities, lack of transportation, work opportunities, and incarceration were sufficient to negate any potential effect of the intervention for increasing treatment participation. However, the null finding highlights a limitation of our study. Some individuals in the pretrial program were mandated to complete treatment through a therapeutic court for substance users. We did not collect data that would enable us to ensure that the treatment and standard care only conditions did not differ with regard to treatment mandate. Additional limitations include participant attrition and modest sample size. As a result, we were not able to detect small effects and may not have captured the experiences of all substance using participants in the pretrial jail diversion program. In addition, our results cannot be generalized to youth. Furthermore, we assessed psychopathy using the PCL-R, and our results are of unclear generalizability to non-clinical (e.g., self-report) measures of psychopathy. Caution is also warranted in generalizing to individuals with minor substance use problems. These limitations are balanced by the strengths of substantial covariate coverage, use of a randomized-controlled longitudinal design to test hypotheses, and the combination of objective and self-report measures of substance use, enabling us to contend that core psychopathic traits may be an important moderator of the effects of BMIs and call for research in larger samples of offenders.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by Grant K23DA027720 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to Marc T. Swogger. Preliminary work on this study was supported by UL1RR024160 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We thank Zach Walsh and Edward Bernstein for essential consultation. We thank Craig McNair and the Pretrial Program for their consistent support during the conduct of this research. We also thank Patrick Walsh for data collection and Faye S. Taxman, James R. McKay, and Tom O’Connor for consultation on conceptualization, design, and analysis.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2003;71(5):862. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews DA, Bonta J, Hoge RD. Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 1990;17:19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, De la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care (WHO Publication No. 92.4) World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. Retrieved December 19, 2007, from the World Wide Web: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/ascii/mhppji.txt. [Google Scholar]

- Benning SD, Patrick CJ, Hicks BM, Blonigen DM, Krueger RF. Factor structure of the psychopathic personality inventory: validity and implications for clinical assessment. Psychological assessment. 2003;15(3):340. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, Heeren T, Levenson S, Hingson R. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard KA, Morgenstern J, Morgan TJ, Lobouvie EW, Bux DA. Assessing consequences of substance use: psychometric properties of the inventory of drug use consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(4):328. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook M, Brieman CL, Kosson DS. Emotion processing in Psychopathy Checklist—assessed psychopathy: A review of the literature. Clinical psychology review. 2013;33(8):979–995. doi: 10.1037/a0030261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2003;71(5):843. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, Woody GE. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleckley H. The Mask of Sanity. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco KM, Carey KB. Psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in psychiatric outpatients. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(4):408. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.4.408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Swogger MT, Houston RJ. A test of the reactive aggression-suicidal behavior hypothesis: is there a case for proactive aggression? Journal of abnormal psychology. 2009;118(1):235. doi: 10.1037/a0014659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Silva K, Duggan C, McCarthy L. Does treatment really make psychopaths worse? A review of the evidence. Journal of personality disorders. 2004;18(2):163–177. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.2.163.32775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej N, Palmstierna T, Berman AH, Kristiansson M, Gumpert CH. Offenders with mental health problems and problematic substance use: Affective psychopathic personality traits as potential barriers to participation in substance abuse interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;46(5):574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden S, Leyro T, Powers M, Otto M. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dybek I, Bischof G, Grothues J, Reinhardt S, Meyer C, Hapke U, John U, Broocks A, Hohagen F, Rumpf HJ. The reliability and validity of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in a German general practice population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67(3):473. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Bains P, Doll H. Substance abuse and dependence in prisoners: a systematic review. Addiction. 2006;101(2):181–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock JT, Woodworth MT, Porter S. Hungry like the wolf: A word-pattern analysis of the language of psychopaths. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 2011;18:102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hare RD. The Hare psychopathy checklist-revised. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, ON: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harris GT, Rice ME. Treatment of psychopathy: A review of empirical findings. In: Patrick CJ, editor. Handbook of psychopathy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LD. The revolving prison door for drug-involved offenders: Challenges and opportunities. Crime & Delinquency. 2001;47(3):462–485. doi: 10.1177/0011128701047003010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse M. The Readiness Ruler as a measure of readiness to change poly-drug use in drug abusers. [Electronic Version] Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3(3):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Compton WM. Screening and brief intervention and referral to treatment for drug use in primary care: back to the drawing board. JAMA. 2014;312(5):488–489. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karberg JC, James DJ. Substance dependence, abuse, and treatment of jail inmates, 2002. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Chang G. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcoholism: Clinical and experimental research. 2003;27(1):67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000046598.59317.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser IM, Leuchter AF, Trivedi MH, Davis LL, Wisniewski SR, Balasubramani GK, Peterson T, Stegman D, Rush AJ. Characteristics of insured and non-insured patients with depression in Star_D. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:995–1004. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubman DI, Yücel M, Kettle JW, Scaffidi A, MacKenzie T, Simmons JG, Allen NB. Responsiveness to drug cues and natural rewards in opiate addiction: associations with later heroin use. Archives of general psychiatry. 2009;66(2):205–212. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Clifford PR, Davis CM. Alcohol treatment research assessment exposure subject reactivity effects: part II. Treatment engagement and involvement. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2007;68(4):529. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE, Ginsburg JI, Weekes JR. Motivational interviewing with offenders. Motivating offenders to change: A guide to enhancing engagement in therapy. 2002:87–102. [Google Scholar]

- McMurran M. Motivational interviewing with offenders: A systematic review. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 2009;14(1):83–100. doi: 10.1348/135532508X278326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles H, Dutheil L, Welsby I, Haider D. ‘Just say no’: A preliminary evaluation of a three-stage model of integrated treatment for substance use problems in conditions of medium security. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2007;18(2):141–159. doi: 10.1080/14789940601101897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people for change. Guilford, New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Talking oneself into change: Motivational interviewing, stages of change, and therapeutic process. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2004;18(4):299–308. doi: 10.1891/jcop.18.4.299.64003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64(6):527. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Miller WR, Hendrickson SM. How does motivational interviewing work? Therapist interpersonal skill predicts client involvement within motivational interviewing sessions. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2005;73(4):590. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ, Karberg JC. State and Federal Prisoners, 2004. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. Drug use and dependence. [Google Scholar]

- Newman CF. Understanding client resistance: Methods for enhancing motivation to change. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1994;1:47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Olver ME, Lewis K, Wong SCP. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2013;4:160–167. doi: 10.1037/a0029769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaschek DLL, Daly TE. Treatment and psychopathy in forensic settings. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2013;18:445–604. [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Project MATCH secondary a priori hypotheses. Addiction. 1997;92:1671–1698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy DE, Kearns MC, Degue S. Reducing psychopathic violence: A review of the treatment literature. Aggression & Violent Behavior. 2013;18:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Harris GT, Cormier CA. An evaluation of a maximum security therapeutic community for psychopaths and other mentally disordered offenders. Law and human behavior. 1992;16(4):399. doi: 10.1007/BF02352266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, Dunn C, Ries R, Donovan D, West II, Maynard C, Atkins DC, Graves MC, Joesch JM, Zarkin GA. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(5):492–501. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubak S, Sandbœk A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice. 2005;55:305–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, Alford DP, Bernstein JA, Lloyd-Travaglini CA, Meli SM, Chaisson CE, Samet JH. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: the ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(5):502–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT. Psychopathy and therapeutic pessimism: Clinical lore or clinical reality? Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22(1):79–112. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto MC, Barbaree HE. Psychopathy, treatment behavior, and sex offender recidivism. Journal of interpersonal violence. 1999;14(12):1235–1248. doi: 10.1177/088626099014012001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran T, Zimmerman M. Factor structure of the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ), a screening questionnaire for DSM-IV axis I disorders. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2004;35(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Johansson P, Andershed H, Kerr M, Eno Louden J. Two subtypes of psychopathic violent offenders that parallel primary and secondary variants. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:395–409. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Monahan J, Mulvey Psychopathy, treatment involvement, & subsequent violence among civil psychiatric patients. Law & Human Behavior. 2002;26:577–603. doi: 10.1023/a:1020993916404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeem JL, Polaschek, Manchak . Appropriate treatment works but how?: Rehabilitating general, psychopathic, and high-risk offenders. In: Skeem JL, Douglas KS, Lillenfeld SO, editors. Psychological science in the courtroom: Consensus and controversy. Guilford; New York: 2009. pp. 358–384. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC. Problem drinkers: Guided self-change treatment. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Steuerwald BL, Kosson DS. Emotional experiences of the psychopath. In: Gacono CB, editor. In The Clinical and Forensic Assessment of Psychopathy: A Practitioner’s Guide. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Swogger MT, Kosson DS. Identifying Subtypes of Criminal Psychopaths A Replication and Extension. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2007;34(8):953–970. doi: 10.1177/0093854807300758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR. The inventory of drug use consequences (InDUC): Test-retest stability and sensitivity to detect change. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16(2):165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utter GH, Young JB, Theard LA, Cropp DM, Mohar CJ, Eisenberg D, Schermer CR, Owen LJ. The effect on problematic drinking behavior of a brief motivational interview shortly after a first arrest for driving under the influence of alcohol: A randomized trial. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2014;76(3):661–671. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.16.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglum P. Antisocial personality disorder and narcotic addiction. In: Millon T, Simonson E, Burket-Smith M, Davis R, editors. Psychopathy: Antisocial, Criminal, and Violent Behaviour. NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: a meta-analytic review. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2006;41(3):328–335. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh Z, Allen LC, Kosson DS. Beyond social deviance: Substance use disorders and the dimensions of psychopathy. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21(3):273–288. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Clark MD, Gingerich R, Meltzer ML. Motivating offenders to change: A guide for probation and parole. US Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NJ, Tamatea A. Challenging the ‘urban myth’of psychopathy untreatability: the High-Risk Personality Programme. Psychology, Crime & Law. 2013;19(5–6):493–510. doi: 10.1080/1068316X.2013.758994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SCP, Hare RD. Guidelines for a psychopathy treatment program. Multi-Health Systems; Toronto, ON: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Woodall WG, Delaney HD, Kunitz SJ, Westerberg VS, Zhou H. A randomized trial of DWI intervention program for first offenders: Intervention outcomes and interactions with Antisocial Personality Disorder among a primarily American Indian Sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(6):974–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32(2):189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Chelminski I. A scale to screen for DSM-IV Axis I disorders in psychiatric out-patients: performance of the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Psychological medicine. 2006;36(11):1601–1611. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. A self-report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses: the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):787–794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Sheeran T. Screening for principal versus comorbid conditions in psychiatric outpatients with the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15(1):110. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]