Abstract

Endothelial dysfunction is more prevalent in African Americans (AAs) compared with whites. The authors hypothesized that nebivolol, a selective β1‐antagonist that stimulates nitric oxide (NO), will improve endothelial function in AAs with hypertension when compared with metoprolol. In a double‐blind, randomized, crossover study, 19 AA hypertensive patients were randomized to a 12‐week treatment period with either nebivolol 10 mg or metoprolol succinate 100 mg daily. Forearm blood flow (FBF) was measured using plethysmography at rest and after intra‐arterial infusion of acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside to estimate endothelium‐dependent and independent vasodilation, respectively. Physiologic vasodilation was assessed during hand‐grip exercise. Measurements were repeated after NO blockade with L‐NG‐monomethylarginine (L‐NMMA) and after inhibition of endothelium‐derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) with tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA). NO blockade with L‐NMMA produced a trend toward greater vasoconstriction during nebivolol compared with metoprolol treatment (21% vs 12% reduction in FBF, P=.06, respectively). This difference was more significant after combined administration of L‐NMMA and TEA (P<.001). Similarly, there was a contribution of NO to exercise‐induced vasodilation during nebivolol but not during metoprolol treatment. There were significantly greater contributions of NO and EDHF to resting vasodilator tone and of NO to exercise‐induced vasodilation with nebivolol compared with metoprolol in AAs with hypertension.

Endothelial dysfunction precipitated by loss of nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability is associated with exposure to cardiovascular risk factors. African Americans (AAs) have a higher burden of hypertension and its associated target organ damage, including nephropathy, stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular mortality.1 In comparison to their white counterparts, AAs have decreased NO bioavailability and worse endothelial function that has been attributed to both decreased production and increased degradation of NO.2, 3, 4, 5

Nebivolol is a third‐generation, β1‐adrenergic receptor antagonist with vasodilatory effects that appear to be independent of β1‐receptor antagonism and related to β3‐receptor agonist effects.6, 7, 8 It stimulates NO release through β3‐receptor and adenosine triphosphate–dependent, P2Y‐receptor activation.6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 In hypertensive patients, vasodilation with nebivolol is evident after a single dose and persists after chronic administration.14, 15 Furthermore, nebivolol increased endothelium‐dependent vasodilation with acetylcholine when compared with atenolol in white patients with hypertension.16

Endothelium‐dependent vasodilation in response to agonists such as acetylcholine and bradykinin is caused by the release of several factors including NO, endothelium‐derived hyperpolarization factor (EDHF), prostaglandins, and others.17 EDHF release may compensate for reduced NO bioavailability in certain disease states and contributes to physiologic vasodilation caused by exercise.17, 18, 19, 20 Although there may be several EDHFs, they all relax vascular smooth muscle via activation of calcium‐dependent potassium channels that can be inhibited with tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA).20 Using these antagonists, we and others have shown that EDHF contributes to resting vasodilator tone and to bradykinin‐mediated vasodilation in healthy patients.17 Furthermore, we found that NO but not EDHF activity is reduced in the forearm vasculature of AAs compared with whites.4

Because of the reduction in NO bioavailability in the vasculature of AAs, we sought to determine whether nebivolol, compared with metoprolol, can selectively improve endothelial function by modulating NO and EDHF activities in AAs with hypertension. We tested the hypothesis that nebivolol, by increasing NO bioavailability, would improve endothelial function compared with matched hypotensive doses of sustained‐release metoprolol in AAs with hypertension.

Methods

Study Design

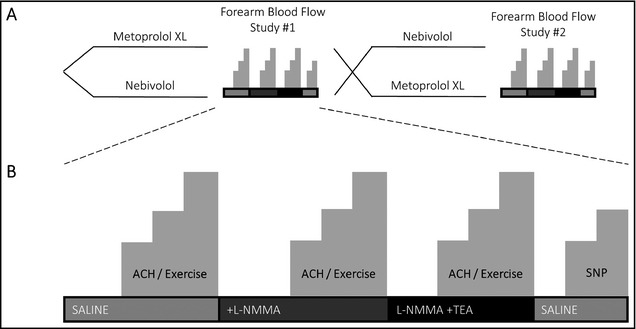

In a randomized, double‐blind, crossover study, patients with resting blood pressure (BP) >135/85 mm Hg were randomized to receive either nebivolol or metoprolol succinate in addition to their current regimen of antihypertensive medications (Figure 1A). Patients with hypertension and BP <135/85 mm Hg at randomization had their regimen altered by decreasing the dose of concomitant medications. The study drug was initiated as either nebivolol 5 mg or metoprolol succinate 50 mg daily. After 2 weeks, the dose of the study drug was increased to either nebivolol 10 mg or metoprolol 100 mg if BP remained >125/80. Patients continued the highest titrated dose of study drug for an additional 10 weeks prior to performance of vascular studies. At the end of the first treatment phase, patients were crossed over into the alternate treatment arm. BP was measured at each visit after a 10‐minute rest period using a mean of three measurements taken 5 minutes apart. The study was reviewed and approved by Emory University's institutional review board. All patients provided written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Study design (A) and protocol (B). ACH indicates acetylcholine; SNP, sodium nitroprusside; L‐NMMA, L‐N G‐monomethylarginine.

Subjects

Self‐identified AA patients aged 22 to 80 years with a history of essential hypertension were recruited. Exclusion criteria included initiation or change in statin or antihypertensive therapy, occurrence of stroke or acute coronary syndrome within 2 months prior to randomization, presence of chronic stable angina, current neoplasm, symptoms of heart failure, aortic stenosis, chronic kidney or liver diseases (creatinine >2.5 mg/dL, liver enzymes more than twice the upper limit of normal), and premenopausal women with the potential for pregnancy. Patients with contraindications to β‐blockade (ie, second‐ or third‐degree atrioventricular block, bradycardia, severe reactive airways disease) were also excluded. Concurrent therapy with angiotensin antagonists (ACE inhibitors or ARBs) was not permitted. Allowable concurrent antihypertensive therapy included thiazide diuretics, calcium channel antagonists, clonidine, and vasodilators. Patients taking β‐adrenergic blockers had their drug changed to the study drug at time of enrollment. Patients with comorbid cardiovascular risk factors including hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and smoking were included as long as there was no recent or planned change in therapy within 2 months of randomization and during the course of the study.

Materials

N G‐mono‐methyl‐L‐arginine (L‐NMMA; Bachem, Laufelfingen, Switzerland) is an analogue of L‐arginine that competitively and irreversibly inhibits the generation of NO from arginine by NO synthases (NOS1, NOS2, and NOS3). Given at 8 μmol/min, it attenuates agonist‐ and exercise‐stimulated FBF, respectively.21, 22 Tetraethylammonium (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO) is a quaternary ammonium compound that selectively blocks voltage‐sensitive potassium channels. When given at 1 mg/min, TEA is known to selectively inhibit K+Ca channels and inhibits bradykinin‐mediated vasodilation.23, 24, 25 Sodium nitroprusside is an endothelium‐independent vasodilator that acts as a direct NO donor.26 Its infusion serves to detect alterations in vascular smooth muscle sensitivity to NO. Acetylcholine (Novartis, East Hanover, NJ) is an endothelium‐dependent vasodilator that stimulates NO release from endothelial cells.27

Measurement of FBF

Patients refrained from exercise, alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine for at least 24 hours before study admission. After an overnight fast in a quiet temperature‐controlled (22°C to 24°C) room, patients received 975 mg of aspirin to inhibit prostacyclin synthesis at least 1 hour prior to the study.28 A 20‐gauge catheter (Teleflex Inc, Research Triangle Park, NC) was inserted in the brachial artery of the nondominant arm under direct ultrasound guidance for intra‐arterial drug infusions, pressure monitoring, and blood sampling. Simultaneous forearm blood flow (FBF) measurements were obtained in both arms using a dual‐channel venous occlusion strain gauge plethysmograph (model EC6, DE Hokanson, Bellevue, WA) as previously described.17, 21 Flow measurements were recorded for approximately 7 seconds every 15 seconds up to eight times, and a mean FBF value in mL/min∙100/mL was computed. Forearm vascular resistance (FVR) was calculated as the mean arterial pressure divided by FBF and expressed as mm Hg per mL/min∙100/mL.

All agents were administered intra‐arterially. Resting FBF measurements were made after 15 minutes of normal saline infusion (1.5 mL/min) and repeated during intra‐arterial infusion of the acetylcholine at 7.5 μg/min, 15 μg/min, and 30 μg/min for 5 minutes each. Physiologic forearm vasodilation was investigated using intermittent handgrip exercise where the evaluated forearm was exercised by squeezing an inflated pneumatic bag as previously described.21, 29 Exercise was performed at 15%, 30%, and 45% of the patient's maximum voluntary grip strength. Each contraction lasted for 5 seconds followed by relaxation for 10 seconds and was repeated for 5 minutes at each workload. FBF was measured in the final 2 minutes of each dose/exercise workload.

After recovery, the acetylcholine and exercise protocol was repeated during inhibition of NO synthesis with the concomitant infusion of L‐NMMA at 8 μmol/min during acetylcholine infusion and 16 μmol/min during exercise. After recovery, while continuing L‐NMMA, TEA was infused intra‐arterially at 1 mg/min and acetylcholine and exercise protocols were repeated. Thus, we measured resting vasomotor tone and acetylcholine‐ and exercise‐mediated vasodilation under control conditions during NO blockade and during combined NO and EDHF blockade, allowing quantification of NO‐ and EDHF‐dependent vasodilation. Finally, sodium nitroprusside was infused intra‐arterially at 1.6 μg/min and 3.2 μg/min for 5 minutes each with FBF and FVR measured with each dose. L‐NMMA and TEA have both been shown to not alter vasodilator responses to nitroprusside (Figure 1B).17

Analysis of Inorganic Nitrite and Nitrate Levels

Plasma nitrite and nitrate were measured from blood samples collected prior to FBF studies into distilled water‐rinsed centrifuge tubes containing 100 mL of 100 mmol/L N‐ethylmaleimide and 5 mL of 0.5 mmol/L EDTA. Extracted plasma was flash frozen and stored at −80°C and subsequently analyzed for nitrite and nitrate levels by ion chromatography (ENO20; Eicom USA, San Diego, CA) as previously described.30

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive patient characteristics were reported as means, standard deviations (SDs), standard errors (in figures), and percentages. A paired Student t test was used to compare BP between treatment phases. Analysis of FBF and FVR measurements was performed using linear mixed‐effects modeling with repeated measures after log‐transformation of the non‐normal and positively skewed variables. An unstructured covariance form was assumed for the repeated measures. In the model, treatment period (metoprolol or nebivolol) and inhibitor (L‐NMMA, TEA, L‐NMMA, and TEA) were added as fixed effects, and patient ID as a random effect. Based on previous studies, with a sample size of 20, we should detect a 10% or greater change between the two drugs in FBF with L‐NMMA or TEA with α=0.05 and power=0.8.15, 16

Results

Patients

Of the 19 patients (13 men and 6 women) recruited, 74% were taking one or more antihypertensive medications, most commonly diuretics and calcium channel antagonists (Table). Fourteen patients (74%) reached the target doses of nebivolol 10 mg and metoprolol 100 mg. Of the five patients who did not require uptitration, two were controlled on nebivolol 5 mg and metoprolol 50 mg, one required nebivolol 5 mg and metoprolol 100 mg, and two required nebivolol 10 mg and metoprolol 50 mg.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Patients

| Hypertensive African Americans (N=19) | |

| Age, y | 51±86 |

| Male/female | 13/6 |

| Diabetes mellitus, No. (%) | 1 (51) |

| Smoker, No. (%) | 7 (368) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, No. (%) | 6 (315) |

| Family history of CAD, No. (%) | 6 (315) |

| Statin therapy, No. (%) | 4 (21) |

| Weight, kg | 965±223 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 325±74 |

| Concurrent antihypertensive drugs, % | |

| Diuretic (thiazide) | 8 (421) |

| Calcium channel antagonist | 5 (263) |

| Nebivolol | Metoprolol Succinate | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| On‐treatment hemodynamic data | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 135±15 | 134±15 | .8 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 81±14 | 81±21 | .8 |

| Resting heart rate, beats per min | 63±8 | 64±9 | .8 |

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation unless otherwise indicated.

Resting Forearm Vascular Tone

Heart rate and blood pressure were similar during both nebivolol and metoprolol treatment periods (Table). Resting vasodilator tone was also similar with the two study agents; FBF 2.8±1.3 mL/min∙100/mL and 2.9±1.2 mL/min∙100/mL (P=.6) and FVR 40.8±17 mm Hg/mL/min∙100/mL and 37.5±12 mm Hg/mL/min∙100/mL (P=.8) with nebivolol and metoprolol, respectively (Figure 2).

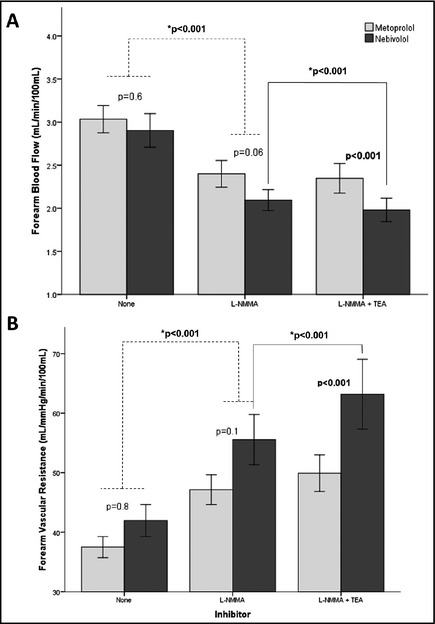

Figure 2.

Contribution of nitric oxide and K+Ca channel activation to resting forearm blood flow (A) and vascular resistance (B) during treatment with nebivolol and metoprolol. Responses to infusion of L‐N G‐monomethylarginine (L‐NMMA) and combined infusions of L‐NMMA and tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) are shown. Non‐starred P values reflect the statistical significance for the comparison between treatment phases (metoprolol vs. nebivolol). Starred (*) P values reflect the statistical significance for the comparison between inhibitors. Data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean.

NO blockade with L‐NMMA reduced resting FBF by 21% with nebivolol and 12% with metoprolol (both P<.001 compared with baseline, P=.06 between groups for comparison of absolute values, and P=.053 for comparison of percent change in FBF). Similarly, FVR increased by 26% with nebivolol and 18% with metoprolol (both P<.001 compared with baseline, P=.1 between groups for comparison of absolute values, and P=.1 for comparison of percentage change in FVR) (Figure 2). Addition of K+Ca channel blockade with TEA to L‐NMMA resulted in further significant reduction in FBF and an increase in FVR with nebivolol but not metoprolol (P<.001) (Figure 2). Thus, there was a greater contribution of NO and EDHF combined to resting blood flow during therapy with nebivolol compared with metoprolol, with NO accounting for the majority of the difference.

Acetylcholine‐Mediated Vasodilation

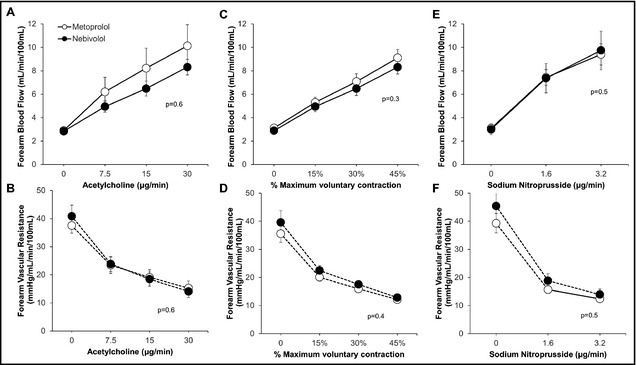

Acetylcholine produced a similar dose‐dependent increase in FBF and a concurrent decrease in FVR with both nebivolol and metoprolol (both P=.6) (Figure 3). L‐NMMA co‐infusion attenuated acetylcholine‐mediated vasodilation during treatment with both drugs, resulting in a 23.1%±27.3% (P=<.001) and a 14.8%±35.5% (P=.002) decrease in FBF with nebivolol and metoprolol, respectively (Figure 4). The difference between the groups did not reach statistical significance (P=.4). Addition of TEA to L‐NMMA did not further impact FBF or FVR during either the nebivolol or metoprolol treatment periods, indicating lack of contribution of EDHF to acetylcholine‐mediated vasodilation with either drug (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Endothelium‐dependent forearm blood flow (A) and forearm vascular resistance (B) changes with acetylcholine, endothelium‐independent changes in forearm blood flow (C) and forearm vascular resistance (D) with sodium nitroprusside, and forearm exercise‐induced changes in forearm blood flow (E) and forearm vascular resistance (F) during treatment with nebivolol and metoprolol. P values are for treatment effect of nebivolol/metoprolol by mixed model. Data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean.

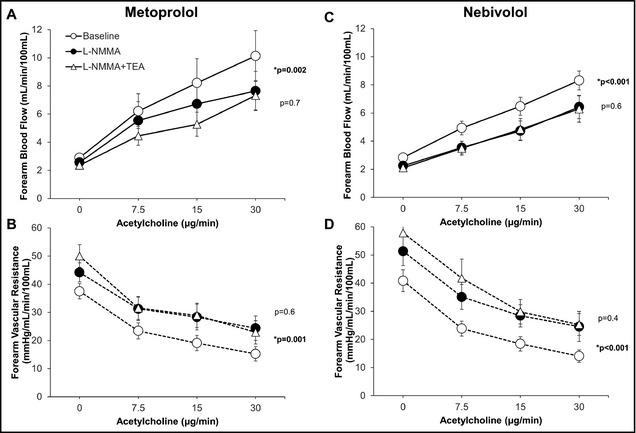

Figure 4.

Contribution of nitric oxide and K+Ca channel activation to acetylcholine‐mediated vasodilation during treatment with nebivolol (A and C) and metoprolol (B and D). Forearm blood flow and forearm vascular resistance responses to increasing doses of acetylcholine alone after initial infusion of L‐N G‐monomethylarginine (L‐NMMA), and combined blockade with L‐NMMA and tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) are shown. P values are for effect of L‐NMMA and TEA by mixed model. *p denotes P value for comparison of L‐NMMA and control, non‐starred p reflects P value for comparison of L‐NMMA and L‐NMMA+TEA. Data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean.

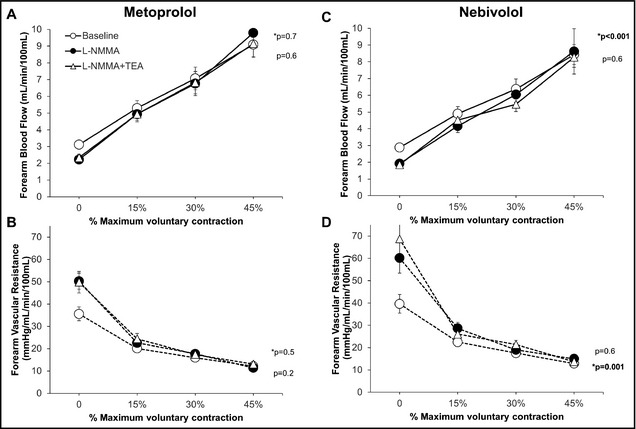

Exercise‐Induced Vasodilation

Graded exercise produced progressive forearm vasodilation that was similar during treatment with nebivolol and metoprolol (P=.3 and P=.4, respectively) (Figure 3C and 3D). With nebivolol, however, NO antagonism with L‐NMMA resulted in a significant decrease in FBF (P=.001) and increase in FVR (P<.001) (Figure 5). There was no significant change in FBF or FVR with L‐NMMA during the metoprolol treatment period (Figure 5). This suggests a significant contribution of NO to exercise‐mediated vasodilation with nebivolol, but not with metoprolol treatment. Combined administration of L‐NMMA and TEA produced no further reduction in FBF or increase in FVR during either the metoprolol or nebivolol treatment periods, indicating lack of contribution of EDHF to exercise‐mediated vasodilation with either β‐antagonist (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Contribution of nitric oxide and K+Ca channel activation to forearm exercise‐mediated vasodilation during treatment with nebivolol (A and C) and metoprolol (B and D). Forearm blood flow and forearm vascular resistance responses to increasing doses of acetylcholine alone, after initial infusion of L‐N G‐monomethylarginine (L‐NMMA), and combined blockade with L‐NMMA and tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) are shown. P values are for effect of L‐NMMA and TEA by mixed model. *p denotes P value for comparison of L‐NMMA and control, non‐starred p reflects P value for comparison of L‐NMMA and L‐NMMA+TEA. Data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean.

Sodium Nitroprusside–Induced Vasodilation

Sodium nitroprusside infusion produced similar vasodilation during treatment with nebivolol and metoprolol (Figure 3E and 3F), indicating no differences in endothelium‐independent vasodilation with these agents.

Plasma Nitrite and Nitrate Levels

Plasma nitrite and nitrate levels were similar during treatment with nebivolol (0.17±0.1 μmol/L and 9.3±3.5 μmol/L, P=.7) and metoprolol (0.17±0.1 μmol/L and 8.7±4.1 μmol/L, P=0.5).

Discussion

Compared with whites, both healthy and hypertensive AAs have diminished basal NO activity and reduced endothelium‐dependent and ‐independent vasodilation.4, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 In this study, we found evidence for NO bioavailability at rest during treatment with both nebivolol and metoprolol succinate in hypertensive AA patients, with a clear trend for a greater contribution of NO during nebivolol therapy. Moreover, after combined blockade of NO and EDHF, there was a significantly greater vasoconstriction during nebivolol compared with metoprolol therapy, suggesting greater contribution of both NO and EDHF combined to resting vasomotor tone during nebivolol treatment. Moreover, the contribution of NO to exercise‐induced vasodilation was greater during treatment with nebivolol compared with metoprolol succinate. This is the first study to explore the role of nebivolol compared with metoprolol in AA hypertensives who have profound abnormalities in NO bioavailability. Specifically, we demonstrate a greater contribution of endothelium‐derived vasodilators to resting FBF and greater contribution of NO to vasodilation during exercise with nebivolol compared with metoprolol. We found no differences in acetylcholine‐mediated vasodilation between these agents, a finding that is different from that reported in white hypertensive patients who received either nebivolol or atenolol.16

We have previously shown that there is no contribution of NO at rest and after acetylcholine in hypertensive patients (no effect of L‐NMMA).37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 Here, we demonstrate that there is some contribution of NO after AA hypertensive patients are treated with β‐adrenergic blockade and further show that this is higher with nebivolol at rest compared with metoprolol. In healthy patients, L‐NMMA reduces resting flow by 30% to 40%. After β‐blockade, we show that even in hypertensive patients, it is restored to approximately half of what it is in healthy patients.

Exercise‐induced vasodilation is a complex process involving multiple vasodilator mechanisms including a modest contribution of NO and various putative EDHFs.4, 21, 44, 45 We previously demonstrated that both NO and EDHF contribute individually to and in concert with exercise‐induced microvascular vasodilation in healthy human forearm circulation. Nebivolol, but not metoprolol, restored functional sympatholysis that is impaired in the working muscle of hypertensive patients.46 In this study, while there was no difference in the magnitude of vasodilation during exercise between treatments, we observed a significant contribution of NO to exercise‐induced vasodilation during the nebivolol but not the metoprolol treatment period. This suggests that nebivolol restores contribution of NO to exercise‐induced vasodilation in AAs with hypertension. Interestingly, neither drug increased the contribution of EDHF to exercise‐induced vasodilation.

In previous studies in hypertensive patients of both ethnicities, we and others found that acetylcholine‐mediated NO release was lower compared with that in normotensive controls.4, 34, 35, 36 In fact, L‐NMMA did not inhibit acetylcholine responses in untreated hypertensive patients. Herein, we show significant NO release in response to acetylcholine during treatment with both β‐receptor antagonists. In a previous study of European patients with hypertension, increased acetylcholine‐mediated NO activity was reported with nebivolol but not with atenolol.16 Improved NO activity with nebivolol may thus account for the benefits compared with atenolol.47

Greater NO activity was found in internal mammary artery and vein specimens from patients pretreated with nebivolol compared with metoprolol.48 In patients with coronary artery disease or hypertension, nebivolol but not atenolol improved flow‐mediated dilation and lowered asymmetric dimethylarginine levels, a naturally occurring amino acid that inhibits endothelial NO synthase.15, 49 Finally, in AA patients with stage 1 hypertension, nebivolol monotherapy increased flow‐mediated dilation and improved arterial wave reflections compared with untreated patients.50 In contrast, no differences between metoprolol succinate and nebivolol were observed in aortic compliance indices in a largely AA population of diabetics.51

Moreover, these experiments were performed in the setting of prostacyclin inhibition. The contribution of the prostacyclin pathway was thus not investigated in this study and may also potentially be affected by β‐blockade. Whether other endogenous vasodilators such as prostacyclin, adenosine, carbon monoxide, and others are affected differentially by nebivolol vs other β‐blockers needs to be studied.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the blinded crossover design and investigation in AA hypertensive patients, who are at particularly high cardiovascular risk and have profound NO abnormalities. We also examined the contribution of both NO and EDHF to resting, acetylcholine‐mediated, and exercise‐induced vasodilation. Limitations include the small sample size and the heterogeneity of the population, which was largely driven by the requirement of repeated intra‐arterial cannulation. The lack of a placebo‐treatment phase would have allowed comparison of either agent with no therapy; however, this was precluded by potential hazards of performing three invasive studies in the same patient. This study also did not include other β‐receptor antagonist comparators such as atenolol. In addition, the interaction of concomitant medications such as thiazides or diuretics with the study drugs on NO bioavailability, while largely controlled by the crossover design and stable dosing, could not be examined.

Conclusions

There was significant contribution of NO and EDHF to resting vasodilator tone and a significant contribution of NO to exercise‐induced vasodilation with nebivolol compared with an equipotent dose of metoprolol succinate. These findings demonstrate selective effects of nebivolol on NO activity in AA patients with hypertension and provide mechanistic insights into endothelial dysfunction in this at‐risk group. Further study is needed to establish whether these observations translate into clinically meaningful outcomes.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by an investigator‐initiated grant from Forest Pharmaceuticals and in part by American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship grant 11POST7140036 (R.B.N.) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR000454.

Disclosures

None of the authors have any conflicts of interests to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the dedicated nursing and support staff of the Emory Clinical Research Network and referring physicians without whom this study would not have been possible.

J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18:223–231. DOI: 10.1111/jch.12649. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01049009

References

- 1. Cooper R, Cutler J, Desvigne‐Nickens P, et al. Trends and disparities in coronary heart disease, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases in the United States: findings of the national conference on cardiovascular disease prevention. Circulation. 2000;102:3137–3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cowie CC, Port FK, Wolfe RA, et al. Disparities in incidence of diabetic end‐stage renal disease according to race and type of diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1074–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Houghton JL, Philbin EF, Strogatz DS, et al. The presence of African American race predicts improvement in coronary endothelial function after supplementary L‐arginine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ozkor MA, Murrow JR, Rahman A, et al. The contribution of nitric oxide and endothelium‐derived hyperpolarizing factor to resting and stimulated vasodilator tone in African Americans and whites. Vasc Med. 2015; 20:14–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalinowski L, Dobrucki IT, Malinski T. Race‐specific differences in endothelial function: predisposition of African Americans to vascular diseases. Circulation. 2004;109:2511–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mason RP, Jacob RF, Corbalan JJ, et al. The favorable kinetics and balance of nebivolol‐stimulated nitric oxide and peroxynitrite release in human endothelial cells. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mason RP, Kubant R, Jacob RF, et al. Effect of nebivolol on endothelial nitric oxide and peroxynitrite release in hypertensive animals: role of antioxidant activity. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;48:862–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van de Water A, Janssens W, Van Neuten J, et al. Pharmacological and hemodynamic profile of nebivolol, a chemically novel, potent, and selective beta 1‐adrenergic antagonist. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1988;11:552–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kalinowski L, Dobrucki LW, Szczepanska‐Konkel M, et al. Third‐generation beta‐blockers stimulate nitric oxide release from endothelial cells through ATP efflux: a novel mechanism for antihypertensive action. Circulation. 2003;107:2747–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mollnau H, Schulz E, Daiber A, et al. Nebivolol prevents vascular NOS III uncoupling in experimental hyperlipidemia and inhibits NADPH oxidase activity in inflammatory cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:615–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cominacini L, Fratta Pasini A, Garbin U, et al. Nebivolol and its 4‐keto derivative increase nitric oxide in endothelial cells by reducing its oxidative inactivation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1838–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fratta Pasini A, Garbin U, Nava MC, et al. Nebivolol decreases oxidative stress in essential hypertensive patients and increases nitric oxide by reducing its oxidative inactivation. J Hypertens. 2005;23:589–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maffei A, Vecchione C, Aretini A, et al. Characterization of nitric oxide release by nebivolol and its metabolites. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arosio E, De Marchi S, Prior M, et al. Effects of nebivolol and atenolol on small arteries and microcirculatory endothelium‐dependent dilation in hypertensive patients undergoing isometric stress. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1793–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lekakis JP, Protogerou A, Papamichael C, et al. Effect of nebivolol and atenolol on brachial artery flow‐mediated vasodilation in patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tzemos N, Lim PO, MacDonald TM. Nebivolol reverses endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension: a randomized, double‐blind, crossover study. Circulation. 2001;104:511–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ozkor MA, Murrow JR, Rahman AM, et al. Endothelium‐derived hyperpolarizing factor determines resting and stimulated forearm vasodilator tone in health and in disease. Circulation. 2011;123:2244–2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Halcox JP, Narayanan S, Cramer‐Joyce L, et al. Characterization of endothelium‐derived hyperpolarizing factor in the human forearm microcirculation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2470–H2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen RA, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium‐dependent hyperpolarization. Beyond nitric oxide and cyclic GMP. Circulation. 1995;92:3337–3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quyyumi AA, Ozkor M. Vasodilation by hyperpolarization: beyond NO. Hypertension. 2006;48:1023–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gilligan DM, Panza JA, Kilcoyne CM, et al. Contribution of endothelium‐derived nitric oxide to exercise‐induced vasodilation. Circulation. 1994;90:2853–2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilligan DMGV, Panza JA, Garcia CE, et al. Selective loss of microvascular endothelial function in human hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1994;90:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Honing ML, Smits P, Morrison PJ, Rabelink TJ. Bradykinin‐induced vasodilation of human forearm resistance vessels is primarily mediated by endothelium‐dependent hyperpolarization. Hypertension. 2000;35:1314–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Langton PD, Nelson MT, Huang Y, Standen NB. Block of calcium‐activated potassium channels in mammalian arterial myocytes by tetraethylammonium ions. Am J Physiol. 1991;260(3 Pt 2):H927–H934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inokuchi K, Hirooka Y, Shimokawa H, et al. Role of endothelium‐derived hyperpolarizing factor in human forearm circulation. Hypertension. 2003;42:919–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palmer RF, Lasseter KC. Drug therapy. Sodium nitroprusside. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chowienczyk PJ, Watts GF, Cockcroft JR, Ritter JM. Impaired endothelium‐dependent vasodilation of forearm resistance vessels in hypercholesterolaemia. Lancet. 1992;340:1430–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heavey DJ, Barrow SE, Hickling NE, Ritter JM. Aspirin causes short‐lived inhibition of bradykinin‐stimulated prostacyclin production in man. Nature. 1985;318:186–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zelis R, Longhurst J, Capone RJ, Mason DT. A comparison of regional blood flow and oxygen utilization during dynamic forearm exercise in normal subjects and patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1974;50:137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bryan NS, Calvert JW, Gundewar S, Lefer DJ. Dietary nitrite restores NO homeostasis and is cardioprotective in endothelial nitric oxide synthase‐deficient mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:468–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Cannon RO III, Panza JA. Racial differences in nitric oxide–mediated vasodilator response to mental stress in the forearm circulation. Hypertension. 1998;31:1235–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Campia U, Choucair WK, Bryant MB, et al. Reduced endothelium‐dependent and ‐independent dilation of conductance arteries in African Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:754–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenbaum DA, Pretorius M, Gainer JV, et al. Ethnicity affects vasodilation, but not endothelial tissue plasminogen activator release, in response to bradykinin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1023–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Panza J, Quyyumi AA, Brush J Jr, Epstein S. Abnormal endothelium‐dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Panza JA, Casino PR, Kilcoyne CM, Quyyumi AA. Role of endothelium‐derived nitric oxide in the abnormal endothelium‐dependent vascular relaxation of patients with essential hypertension. Circulation. 1993;87:1468–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Taddei S, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, et al. Effect of calcium antagonist or beta blockade treatment on nitric oxide‐dependent vasodilation and oxidative stress in essential hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1379–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Panza JA, Quyyumi AA, Callahan TS, Epstein SE. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on endothelium‐dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Panza JA, Quyyumi AA, Brush JE Jr, Epstein SE. Abnormal endothelium‐dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Panza JA, Garcia CE, Kilcoyne CM, et al. Impaired endothelium‐dependent vasodilation in patients with essential hypertension Evidence that nitric oxide abnormality is not localized to a single signal transduction pathway. Circulation. 1995;91:1732–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Panza JA, Casino PR, Kilcoyne CM, Quyyumi AA. Impaired endothelium‐dependent vasodilation in patients with essential hypertension: evidence that the abnormality is not at the muscarinic receptor level. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Quyyumi AA, et al. Selective defect in nitric oxide synthesis may explain the impaired endothelium‐dependent vasodilation in patients with essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97:851–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Quyyumi AA, et al. Reduced nitric oxide‐dependent forearm vasodilation in normotensive blacks compared to whites. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:7062–7062. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cardillo C, Kilcoyne CM, Cannon RO 3rd, Panza JA. Impairment of the nitric oxide‐mediated vasodilator response to mental stress in hypertensive but not in hypercholesterolemic patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1207–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schrage WG, Joyner MJ, Dinenno FA. Local inhibition of nitric oxide and prostaglandins independently reduces forearm exercise hyperaemia in humans. J Physiol. 2004;557(Pt 2):599–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shoemaker JK, Halliwill JR, Hughson RL, Joyner MJ. Contributions of acetylcholine and nitric oxide to forearm blood flow at exercise onset and recovery. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(5 Pt 2):H2388–H2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Price A, Raheja P, Wang Z, et al. Differential effects of nebivolol versus metoprolol on functional sympatholysis in hypertensive humans. Hypertension. 2013;61:1263–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Basile JN. One size does not fit all: the role of vasodilating beta‐blockers in controlling hypertension as a means of reducing cardiovascular and stroke risk. Am J Med. 2010;123(7 Suppl 1):S9–S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bayar E, Ilhan G, Furat C, et al. The effect of different beta‐blockers on vascular graft nitric oxide levels: comparison of nebivolol versus metoprolol. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;47:204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pasini AF, Garbin U, Stranieri C, et al. Nebivolol treatment reduces serum levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine and improves endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:1251–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Merchant N, Searles CD, Pandian A, et al. Nebivolol in high‐risk, obese African Americans with stage 1 hypertension: effects on blood pressure, vascular compliance, and endothelial function. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2009;11:720–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Briasoulis A, Oliva R, Kalaitzidis R, et al. Effects of nebivolol on aortic compliance in patients with diabetes and maximal renin angiotensin system blockade: the EFFORT study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2013;15:473–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]