Abstract

Black carbon (BC) is a significant component of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air pollution, which has been linked to a series of adverse health effects, in particular premature mortality. Recent scientific research indicates that BC also plays an important role in climate change. Therefore, controlling black carbon emissions provides an opportunity for a double dividend. This study quantifies the national burden of mortality and morbidity attributable to exposure to ambient BC in the United States (US). We use GEOS–Chem, a global 3-D model of atmospheric composition to estimate the 2010 annual average BC levels at 0.5 × 0.667° resolution, and then re-grid to 12-km grid resolution across the continental US. Using PM2.5 mortality risk coefficient drawn from the American Cancer Society cohort study, the numbers of deaths due to BC exposure were estimated for each 12-km grid, and then aggregated to the county, state and national level. Given evidence that BC particles may pose a greater risk on human health than other components of PM2.5, we also conducted sensitivity analysis using BC-specific risk coefficients drawn from recent literature. We estimated approximately 14,000 deaths to result from the 2010 BC levels, and hundreds of thousands of illness cases, ranging from hospitalizations and emergency department visits to minor respiratory symptoms. Sensitivity analysis indicates that the total BC-related mortality could be even significantly larger than the above mortality estimate. Our findings indicate that controlling BC emissions would have substantial benefits for public health in the US.

Keywords: Air pollution, Black carbon, Mortality, Public health burden

Graphical Abstract

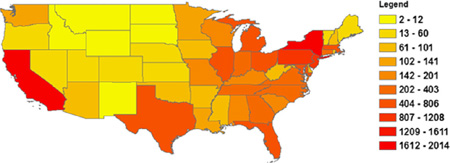

Annual premature mortality by State attributed to exposure to ambient black carbon in the United States in 2010.

1. Introduction

Black carbon (BC) is a significant component of ambient fine particulate matter (PM <= 2.5 µm in aerodynamic diameter; PM2.5) air pollution. Recent scientific evidence has indicated that BC is the most strongly light-absorbing component of PM2.5. BC absorbs solar radiation, influences cloud processes, and alters the melting of snow and ice cover, and thus plays an important role in the Earth’s climate system (Bond et al., 2013). In addition to its climate effects, BC has been associated with adverse effects on human health (e.g. Janssen et al., 2011; Laden et al., 2006). Some suggested that BC may pose greater health risk as indicated by the higher effect estimates per mass unit for BC particles compared with PM mass as a whole (Janssen et al., 2011, 2012). Therefore, mitigating climate change through controlling BC emissions is likely to generate substantial co-benefits for human health.

Black carbon is emitted from a variety of combustion processes, mainly the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, biofuels, and biomass (EPA, 2012). The US contributes about 8% of the global emissions of BC (EPA, 2012). Within the US, BC is estimated to account for approximately 12% of all direct PM2.5 emissions in 2005, and transport was the largest source of BC emissions in that year, which contributed to about 52% of the total BC emissions in the US, followed by open biomass burning (35%) (EPA, 2012).

Given the significance of BC both as a health effect agent and a climate forcing pollutant, the total health burden of BC would provide valuable information in developing climate and air pollution strategies. BC emissions will be substantially reduced by 2030 due to recently promulgated regulations, including the emissions standards for new engines and the retrofit programs for in-use mobile diesel engines (EPA), 2012). The present study aims to quantify the public health burden attributable to the ambient BC levels within the continental US in 2010 prior to the expected improvement in BC levels in the future. Earlier national-level particle-related health impacts assessment have focused on total, undifferentiated PM2.5 mass. For example, using the photochemical Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model results in conjunction with ambient monitored data, Fann et al. (2012) estimated 130,000 PM2.5-related deaths in 2005. Based on observational data, it has been estimated that BC comprises approximately 5–10% of average urban PM2.5 mass in the US (EPA, 2012). However, it is difficult to estimate the BC-related health outcomes based on the PM2.5-related estimates owing to the fact that spatial variability in concentrations for BC is often larger than for PM2.5, particularly in urban and populous areas. Also, given recent evidence that BC particles may pose a greater risk on human heath than other components of PM2.5, it is important to assess the national health impacts of BC separately.

We use an integrated procedure that combines exposure assessment, exposure-response relationships and baseline health statistics to quantify the public health burden attributed to BC exposure. Our methods are consistent with those used previously by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) to assess the public health burden attributed to criteria air pollutants in the US, such as particulate matter and ozone (Fann et al., 2012; Hubbell et al., 2005), and also those used to assess the global burden of disease (Anenberg et al., 2010; Cohen et al., 2005; Ostro, 2004). To estimate ambient BC concentrations, we use GEOS–Chem, a global 3-D model of atmospheric composition with a horizontal resolution of 0.5° latitude × 0.667° longitude (approximately 55 km × 55 km) over North America. Since observational data for BC are only available at limited monitoring locations, using simulated concentrations allows us to capture the BC impacts across the entire continental US.

We quantify the excess mortality and morbidity impacts associated with anthropogenic BC emissions nationwide and also the effects at the State and county level. In addition, previous health risk assessments of PM2.5 generally assume that all constituents of PM2.5, including BC, are equally toxic (Levy et al., 2012). We conducted a literature review of epidemiologic studies that investigate the health risks from both BC and total PM2.5 mass. In this analysis, we use both the concentration response (CR) functions for PM2.5 and several BC-specific CR functions to indicate the possible species potency of BC Finally, we discuss the significant sources of uncertainty associated with the health impact assessment and quantify their impacts on incidence estimates.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the current epidemiologic literature on the health effects of BC and describes the methods used to quantify the public health burden (mortality and morbidity) associated with BC exposure in the US. Section 3 presents our estimates of BC-related premature mortality at the nation, State and county level, as well as the national estimates of various morbidity effects. Section 3 also discusses the uncertainty in our estimates. Section 4 summarizes the major conclusions of this study and issues to be further investigated in future work.

2. Methods

2.1. Health effects of ambient black carbon pollution

The negative impacts of PM2.5 on public health have been well documented by epidemiological studies. Time-series studies of the short-term effects of air pollutants, conducted around the world, have consistently reported significant associations between daily mortality and daily exposure to PM2.5 (Ostro, 2004). Cohort studies usually aim at investigating possible long-term chronic effects of exposure to air pollution. Two large-scale cohort studies conducted in the U.S. – the Harvard Six Cities Study and the American Cancer Society (ACS) study – both reported increased mortality associated with an increase in annual average PM2.5 levels (Dockery et al., 1993; Krewski et al., 2000, 2009; Laden et al., 2006; Pope III et al., 2002, 1995).

While existing epidemiological studies provide compelling evidence that PM2.5 increases mortality rates, it is uncertain whether some components of PM2.5 have a stronger relationship with mortality than other components. Some studies report that traffic-related fine particulate air pollution, indicated by black carbon, may pose greater risk on human health than PM2.5 from other sources (Gan et al., 2011; Laden et al., 2006; Peng et al., 2009), while others report that some other constituents of PM2.5, such as sulfates or organic carbon have stronger or more robust associations with adverse health effects (Ostro et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010). However, in spite of this evidence, U.S. EPA maintains that “there is insufficient information at present to differentiate the health effects of the various constituents of PM2.5” and “the limited scientific evidence that is currently available about the health effects of BC is generally consistent with the general PM2.5 health literature” (EPA, 2012).

A recent systematic review on health effects of black carbon performed by the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe found that effect estimates from both short- and long-term studies are much higher for BC compared to PM10 and PM2.5 when the particulate measures are expressed per µg/m3 (Janssen et al., 2012). This report suggests that BC might be a better indicator of harmful particulate substances from combustion sources (especially traffic) than undifferentiated PM2.5 mass (Janssen et al., 2012). Moreover, Janssen et al. (2011) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of health effects of BC compared with PM2.5 based on data from studies that measured both exposures. The study found that the pooled estimates of relative risk per 1 µg/m3 for all-cause mortality related to long-term exposure to PM2.5 and BC are 1.007 and 1.06, respectively, suggesting that the concentration–response coefficient β for BC could be up to ten times larger than that for PM2.5.

Given the uncertainty with regard to the species potency of BC, we reviewed existing epidemiological studies that report the health effects of both PM2.5 and BC. Both time-series studies of the short-term effects and cohort studies of long-term chronic effects were reviewed. As shown in Tables AI and AII in the Appendix A, our review indicates that effect estimates for BC are mostly higher than those for PM in terms of effect per µg/m3 particulate. Among the studies we found that report the effects of both PM2.5 and BC in the same analysis, ratios of BC/PM2.5 effects vary from 3 to 27.7 for long-term mortality by different causes (Table A.I), and from 0.33 to 50 for short-term mortality or morbidity by different causes (Table A.II). Levy et al. (2012) is the only study we found that reports a smaller effect of BC than the effect of PM2.5. That study conducted a meta-analysis that pooled existing short-term mortality estimates for the individual constituents as well as the total PM2.5 mass. However, the meta-analysis includes three studies in the early 2000s that relied on coefficient of haze (COH) as a measurement of BC, and all these studies found a significant smaller effect of COH than that of PM2.5.

Janssen et al. (2011) summarize six studies that include both single-and two-pollutant models of time-series studies including PM (PM10 or PM2.5) and BC (measured as black smoke in all the studies). It was found that the effect of PM was reduced or became negative when moving from single- to two-pollutant model in all six studies, whereas the effect of BC was increased in half of the studies and reduced in the remaining studies. The fact that the effect of PM diminishes or disappears when BC is controlled in the model also supports the argument that BC may pose greater toxicity than the other components of PM2.5.

Our review provides supporting evidence that BC may be more toxic than the other components of PM2.5 and thus the effect estimates for BC is larger than that of undifferentiated PM2.5 mass when expressed as effect per unit of concentration. However, the existing studies are subject to several caveats. First, as shown in Tables AI and AII, the correlations1 between PM2.5 and BC reported in the studies we review are generally high (greater than 0.5 in most cases). In this case, it may be difficult to estimate separate effects of PM2.5 and BC via regression analysis. For example, Peng et al. (2009) argues that any reduction in effect size of either component when moving from the single-pollutant to the multipollutant model could be a result of the correlations between components. Also, as argued by Smith et al. (2010), it may be difficult to draw conclusions about the health effects of individual species because atmospheric black carbon, ozone, and sulfate are associated and could interact with related toxic species. Second, many studies focus on the effects of PM and BC in a single metropolitan area. In urban environments, both spatial and temporal variations of BC are greater than that of PM since BC is mostly governed by vehicle exhaust emissions, while PM concentrations are also governed by regional non-traffic emissions (Janssen et al., 2011; Reche et al., 2011). For example, Kinney et al. (2000) measured concentrations of PM2.5 and elemental carbon (EC) on sidewalks in a community in New York City. They reported that mean concentrations of PM2.5 exhibited only modest site-to-site variation (37–47 µg/m3), whereas EC concentrations varied 4-fold across sites (from 1.5 to 6 µg/m3), and were associated with bus and truck counts on adjacent streets. Also, in a study on the long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and the risk of coronary heart disease hospitalization and mortality in metropolitan Vancouver, Canada (Gan et al., 2011), the variation of PM2.5 concentrations (mean value: 4.08 µg/m3; standard deviation (SD): 1.63) is much smaller compared to that of BC concentrations (mean value: 1.49 µg/m3; SD: 1.1). Relatively small variation of PM2.5 may explain the reason that the effect of PM2.5 is attenuated when BC is included in the model. Third, in multi-city studies BC concentrations measured at a single outdoor monitoring site have often been used to reflect exposure within a city. However, within-city variability in concentrations for BC is larger than for PM2.5 owing to the considerable effect of local primary combustion sources, especially traffic, on BC concentrations (Janssen et al., 2012). Within-city variability may exceed between-city variability, which underlines the importance of taking into account small-scale variations in BC in epidemiological studies (Janssen et al., 2012).

In summary, current epidemiology studies provide supporting evidence that BC may be more harmful than other constitutes of PM2.5, but evidence to differentiate the health effects of the constituents of PM2.5 is still insufficient. Given this, for our main analysis we use a risk estimate for PM2.5 drawn from epidemiological studies to estimate BC-related premature mortality, the most significant health outcomes due to exposure to air pollution. In sensitivity analyses, we also apply BC-specific mortality risk estimates to reflect the species potency. For morbidity, we use risk estimates for PM from epidemiological studies.

2.2. Methods for quantifying public health burden

2.2.1. Overview of the method

Our quantitative assessment of the health impacts of ambient BC pollution is based on the following components: ambient BC concentration assessment based on air quality modeling, the affected population, the health effects of interest (e.g. mortality, morbidity), the baseline incidences of those health effects, and concentration–response functions abstracted from epidemiologic literature. These factors are combined in an integrated procedure using a health impact function. A log-linear health impact function to quantify the excess mortality or morbidity attributed to air pollution is (Anenberg et al., 2012; Li et al., 2010):

| (1) |

where,

Δy: BC attributable health endpoints (i.e. mortality or morbidity);

β: concentration–response coefficient from epidemiological studies (increase in the health endpoint assessed per unit increase in BC);

Δx: change in air quality, taken here as the modeled BC concentration;

y0: the baseline incidence rates for the health endpoint assessed; and

Pop: the affected population, i.e. the number of people exposed to ambient BC pollution.

Here we use BenMAP (Environmental Benefits Mapping and Analysis Program, version 4.0.67 (Abt Associates, 2013)) to calculate the health impacts of exposure to BC. In the following sections, we first describe the GEOS–Chem air quality model used to simulate annual average BC concentrations across the continental U.S. We then discuss how we select the concentration–response coefficient (β) used to estimate BC-related health impacts, and how we characterized the affected population (Pop) and the baseline incidence rates (y0) in Eq. (1).

2.2.2. Modeling annual average pollutant concentrations

To simulate the annual average BC concentrations across the continental US., we use GEOS–Chem (Bey et al., 2001) (www.geos-chem.org), a global 3-D model of atmospheric composition driven by assimilated meteorological observations from the Goddard Earth Observing System (GEOS) of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Global Modeling Assimilation Office. Global simulations are performed at the 4° latitude × 5° longitude degree resolution, with a six month spin-up beginning in July 2009, through the end of 2010. Simulated 3-hourly concentrations from this global calculation are used as the boundary conditions to drive a higher resolution nested simulation over North America at the 0.5° latitude by 0.667° longitude resolution (Chen et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2004). We then convert the model results to the national 12 × 12 km2 grid using a two-step process. GEOS–Chem binary punch output is first converted to Climate Forecasting compliant NetCDF with PseudoNetCDF (pseudonetcdf.googlecode.com), and then regridded using a first-order conservative method as implemented in the Climate Data Operators (code.zmaw.de/projects/cdo). The 12 × 12 km2 resolution is required by the standard BenMAP configuration to evaluate gridded air quality model output.

GEOS–Chem simulations include treatment of primary elemental (BC) and organic (OC) carbonaceous aerosol (Park et al., 2003). BC is emitted as a hydrophobic species (80%) that converts to hydrophilic carbon with an e-folding time of 1.15 days. Global fossil fuel and biofuel emissions of BC are from Bond et al. (2007). Over North America, these values are replaced by the inventory of Cooke et al. (1999), with top-down monthly seasonality imposed from Park et al. (2003). Monthly emissions of BC from biomass burning are from the third version of the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED3) (Giglio et al., 2010; van der Werf et al., 2010). Wet deposition of aerosols includes large-scale precipitation and convective scavenging (Liu et al., 2001). Dry deposition is calculated using a resistance in series scheme (Wesely, 1989) that depends on meteorology and local land surface type.

In addition to carbonaceous species, fine mode aerosol in GEOS– Chem includes sulfate ammonium nitrate (Fountoukis and Nenes, 2007; Park et al., 2004), dust, and sea salt (Jaeglé et al., 2011). We did not consider here the secondary organic aerosol, which likely constitutes a significant fraction of PM2.5 concentrations (Jimenez et al., 2009).

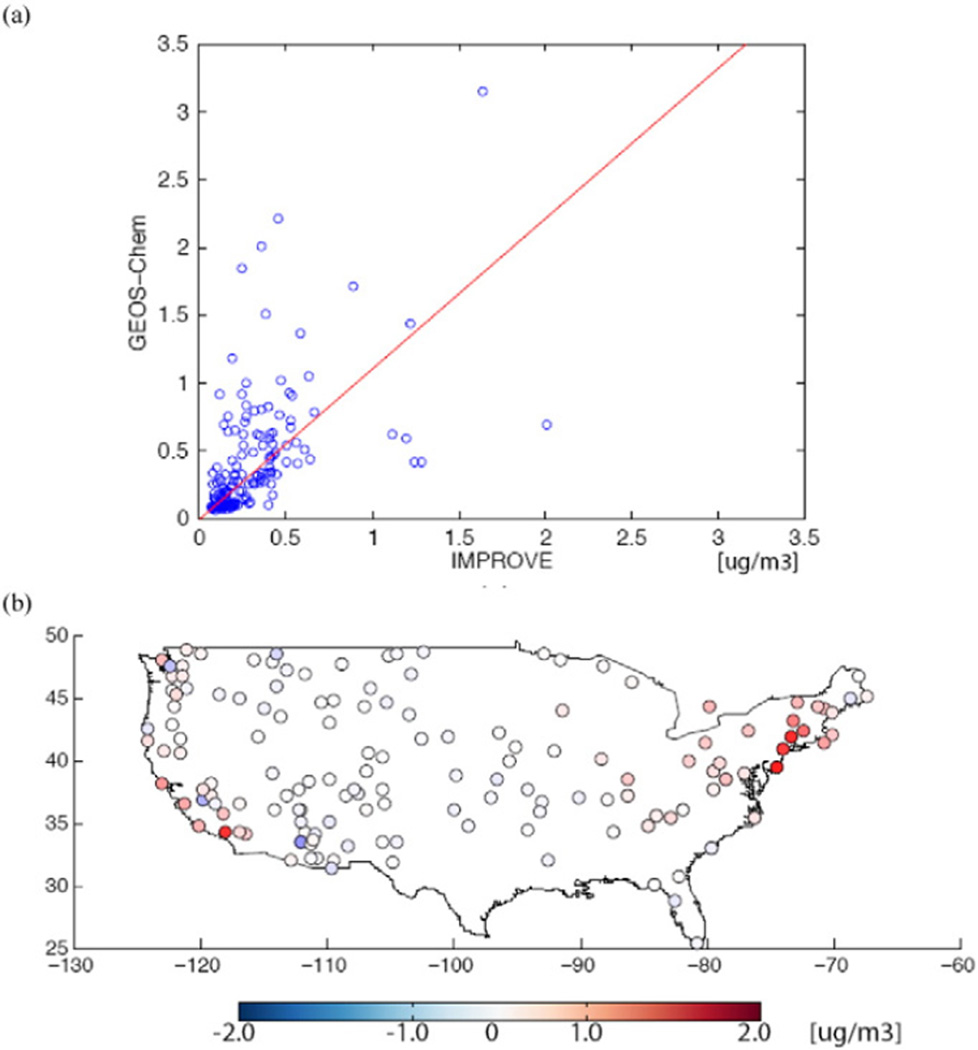

Surface level BC and PM2.5 concentrations in GEOS–Chem have been evaluated with in situ observations in the U.S. in numerous studies (Duncan Fairlie et al., 2007; Heald et al., 2012; Henze et al., 2009; Leibensperger et al., 2012; Mao et al., 2013, 2011; Park et al., 2003, 2004, 2006; Pye et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). The initial BC estimates from Park et al. (2003) showed decent skill in simulating seasonal annual average BC concentrations (R2 from 0.68 to 0.82, slopes of reduced major axis regressions from 0.83 to 1.17) compared to observations from the 24 h average concentrations collected one out of 3 days at IMPROVE sites (Malm et al., 1994) (http://vista.cira.colostate.edu/improve). More recently, GEOS–Chem BC simulations have been evaluated in the Western US by Mao et al. (2011, 2013) for 2006, using a previous version of the GFED biomass burning inventory (van der Werf et al., 2006). Mao et al. (2013) found the model performed well for locations at elevations less than 1 km above sea level, while performance at mountainous sites was strongly impacted by uncertainties in the biomass burning emissions as well as model resolution. Here we reevaluate the model BC compared to measurements from IMPROVE, see Fig. 2 and discussion in Section 3.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of the modeled BC concentrations compared to measurements: (a) Results of a regression fit; and (b) The spatial plot of the model error.

2.2.3. Selection of concentration–response relationships

We estimate both mortality and morbidity associated with BC exposure in this study, including premature deaths from long-term exposure, chronic bronchitis, respiratory and cardiovascular-related hospital admissions, asthma-related emergency room visits, acute bronchitis, respiratory symptoms (lower and upper), and lost work days and minor restricted activity days.

As discussed above, in our main analysis we use risk estimates for PM2.5 to estimate BC-related long-term mortality. We select the estimate from the recent Krewski et al. (2009) extended analysis of the American Cancer Society (ACS) study, which is a prospective cohort study that includes a large population (500,000 adults) over 116US cities. The mortality risk estimates from the ACS study have been used to assess the health burden associated with exposure to ambient PM2.5 in the US and globally (Anenberg et al., 2010; Fann et al., 2012; Punger and West, 2013). We apply the all-cause mortality risk estimate from Krewski et al. (2009) to estimate national BC-related premature mortality as well as the spatial distribution of mortality (mortality by State and county). In a sensitivity analysis, we apply the pooled BC-specific long-term mortality risk estimate from a recent meta-analysis of health effects of BC (Janssen et al., 2011) to estimate national BC-related mortality. In order to reflect the uncertainty associated with the species potency of BC, we also apply to the national mortality estimate two probability distribution functions (PDFs) that combine the Janssen and Krewski estimates: One as a uniform distribution and the other as a triangular distribution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated black carbon-related health impacts in the U.S. due to 2010 modeled air quality.

| Health endpoint | PDF of concentration–response coefficient (β) |

Reference of β (age group) |

Annual estimates (95% Confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | |||

| Adult all-cause | Normal (0.005827, 0.000963) | Krewski et al. (2009) (age ≥30) | 13,910 (9419–18,391) |

| Normal (0.05827, 0.009524) | Janssen et al. (2011) (age ≥30) | 133,807 (92,259–174,523) | |

| Uniform (0.005827, 0.05827) | Krewski et al. (2009) & | 74,689 (17,026–131,050) | |

| Triangular (0.005827, 0.05827) | Janssen et al. (2011) (age ≥30) | 74,882 (27,791–120,969) | |

| Infant | Normal (0.006766, 0.007339) | Woodruff et al. (1997) (age b1) | 32 (13–52) |

| Morbidity | |||

| Hospital admissions – all respiratory | Normal (0.00207, 0.0004464) | Zanobetti et al. (2009) (age N64) | 3380 (1952–4805) |

| Hospital admissions – all cardiovascular | Normal (0.00189, 0.0002832) | Zanobetti et al. (2009) (age N64) | 4344 (3070–5618) |

| Emergency room visits for asthma | Normal (0.0056, 0.0021) | Mar et al. (2010) (all ages) | 10,567 (2804–18,290) |

| Acute bronchitis | Normal (0.02721, 0.017) | Dockery et al. (1996) (ages 8–12) | 20,913 (−4983–45,928) |

| Chronic bronchitis | Normal (0.0137, 0.006796) | Abbey et al. (1994) (age N27) | 9604 (269–18,799) |

| Lower respiratory symptoms | Normal (0.019, 0.006) | Schwartz and Neas (2000) (ages 7–14) | 269,180 (103,588–432,608) |

| Upper respiratory symptoms | Normal (0.0036, 0.0015) | Pope III et al. (1991) (ages 9–11) | 389,951 (71,557–708,006) |

| Asthma exacerbation Cough | Normal (0.00099, 0.00075) | Ostro et al. (2001) (ages 6–18) | 253,806 (−123,529–630,696) |

| Shortness of breath | Normal (0.0026, 0.0013) | 364,800 (−7312–735,972) | |

| Wheeze | Normal (0.0019, 0.0008) | 577,220 (109,712–1,044,186) | |

| Work loss days | Normal (0.0046, 0.00036) | Ostro (1987) (ages 18–64) | 1,910,323 (1,618,200–2,202,217) |

| Minor restricted-activity days | Normal (0.007410, 0.000700) | Ostro and Rothschild (1989) (ages 18–64) | 11,332,839 (9,244,613–13,417,870) |

For morbidity, we consider the same health outcomes that were estimated in Fann et al. (2012), which assessed the national public health burden associated with PM2.5 in the US. For each health outcome, BenMAP contains a library of concentration–response functions, and we select the one from the study that concerned the population over the broadest geographic area. The health endpoints considered, their concentration–response coefficients β (mean values and probability distribution functions, PDFs), and references of β are listed in Table 1.

2.2.4. Exposed population and baseline incidence rates

We use the 2010 population and baseline incidence rates data that have been preloaded in BenMAP. BenMAP uses 2010 U.S. Census block-level population data, and aggregates to population grid-cells at different scales (Abt Associates, 2013). We use the population at the national 12-km grid resolution, and the modeled BC concentrations are matched with the population in each 12-km grid cell. We assume that the modeled BC value in each grid is the best measure of population exposure in that grid. Also, the BenMAP population data are stratified by age as well as other demographic categories such as sex, race and ethnicity. We use the population data that are consistent with the age groups in the original epidemiological studies from which we draw the risk estimates β (see Table 1).

To estimate national mortality rates, the BenMAP group used individual-level mortality data from 2004 to 2006 for the whole United States from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (Abt Associates, 2013). These data were combined with U.S. Census Bureau postcensal population estimates to estimate age-, cause-, and county-specific mortality rates. The age- and county-specific mortality rates in 2010 that were used in this study were estimated using adjustment factors, which were calculated based on a series of Census Bureau projected national mortality rates (Table A.III). Hospitalizations and emergency room visits were calculated using data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, which is a family of health care databases developed through a Federal-State-Industry partnership and sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Table A.III). The other morbidity incidence and prevalence rates used in this study were estimated using national or regional averages depending on the best available data sources (Table A.IV).

2.2.5. Public health burden calculation

Using the modeled BC concentrations, concentration–response coefficients, population and baseline incidence or prevalence data, we calculated the number of excess deaths and illnesses due to BC exposure nationwide. In estimating the 95% confidence interval (CI)of the national estimates, the only source of uncertainty that is taken into account is the uncertainty in β values. The uncertainty analysis was conducted in BenMAP using Monte Carlo simulation with a sample size of 5000. We explored the effects of uncertainties in the BC risk estimate via sensitivity analyses, as noted above. Other sources of uncertainty are discussed qualitatively. We also estimated the excess number of deaths and percent of baseline mortality by State and county and mapped the spatial variations in mortality and in percent of baseline mortality using the mean value of the risk estimate (β) for all-cause mortality from Krewski et al. (2009).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. BC air quality simulation

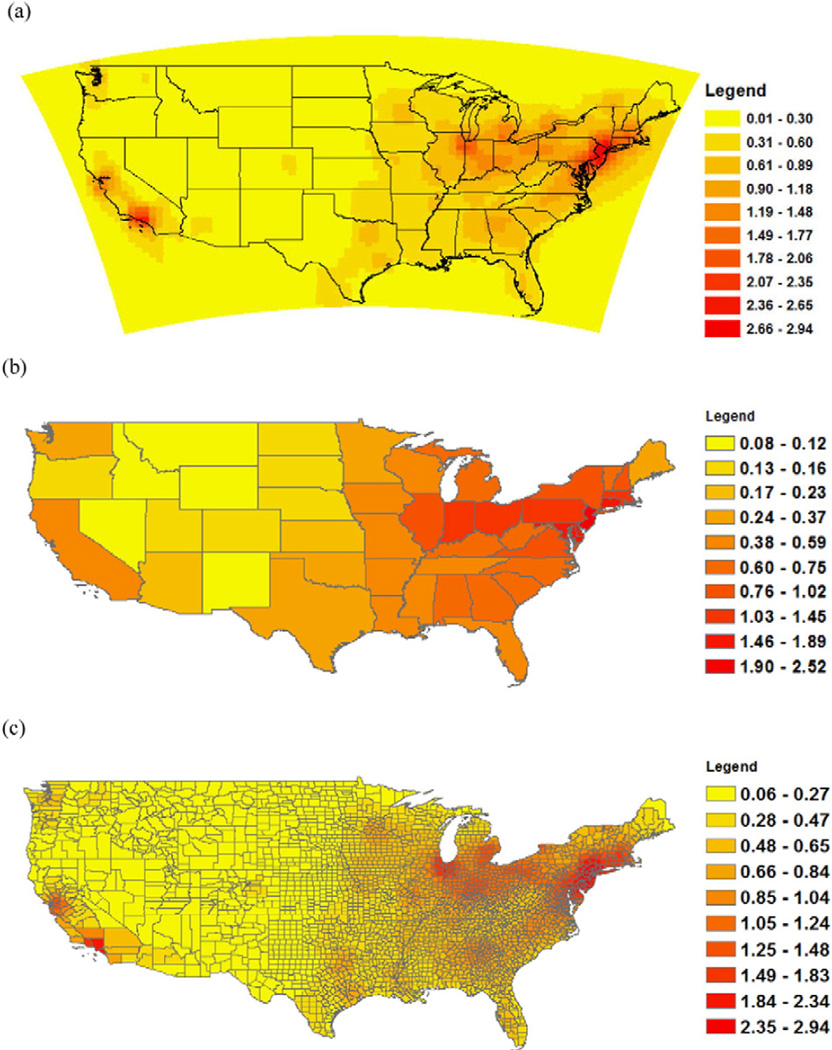

Fig. 1(a) shows the simulated annual average BC concentrations from anthropogenic sources in 2010. The maximum simulated BC value in the continental US is 3.0 µg/m3, the mean BC value is 0.3 µg/m3, and the 95th percentile value is about 1.0 µg/m3. In general, the highest BC values are in the northeastern United States, with some ‘hotspots’ in California.

Fig. 1.

Simulated annual average black carbon concentrations in 2010: (a) At 0.5 × 0.667° resolution; (b) Aggregated to State; and (c) Aggregated to county (Unit: µg/m3).

Fig. 1 (b) and (c) show the spatially-weighted average concentrations in 2010 at the State and county level, respectively. At the State level, New Jersey had the highest spatially-weighted annual average BC concentration in 2010 (2.5 µg/m3), followed by Delaware (1.9 µg/m3) and Connecticut (1.7 µg/m3). At the county level, the top 10 counties that have the highest average levels of BC are all located in New Jersey and New York and surrounding New York City (NYC). These counties are Bergen, Passaic, Somerset, Mercer, Morris, Essex and Middlesex in New Jersey, and Bronx, Rockland New York in New York.

Our evaluation of the modeled BC concentrations compared to measurements from IMPROVE indicates that the annual average BC simulations have a normalized mean bias of 0.10%, a standard error of 0.39 µg/m3. The slope of a reduced major axis fit through the origin is 1.10 (Fig. 2(a)). The spatial plot of the model error (GEOS–Chem – IMPROVE) in Fig. 2(b) shows the model to overestimate BC concentrations in the Northeast and California. This is likely owing to the use of BC emission factors that may not accurately reflect decreasing trends in BC from particulate standards for diesels (Murphy et al., 2011).

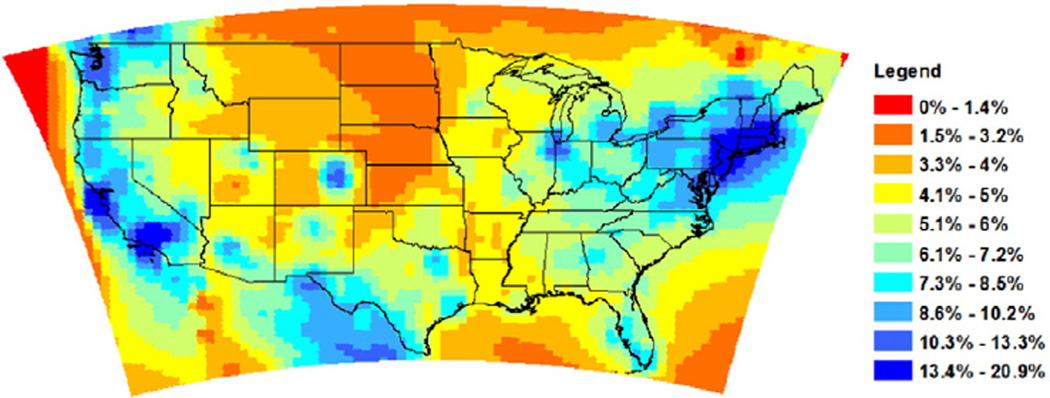

3.2. Comparing the spatial variations of BC to total PM2.5 mass

In order to quantitatively compare the spatial variations of BC to total PM2.5 mass, we simulated annual average PM2.5 concentrations from anthropogenic sources over North America in the same year, and calculated the ratio of BC to total PM2.5. As shown in Fig. 3, the ratio of annual average BC to total PM2.5 mass concentration varies in the range of [0–20.9%] across the continental US, and the ratio tends to be larger in the northeast and the West Coast regions, particularly in populous urban centers. This is explained by the fact that BC is a primary aerosol whose distribution is more closely coupled with population centers.

Fig. 3.

Ratio of BC to PM2.5 annual average concentration in 2010.

3.3. Estimates of national mortality and morbidity attributed to BC exposure in 2010

Using the all-cause mortality risk estimate for PM2.5 among adults aged over 30 drawn from the Krewski et al. (2009), we estimate 14,000 (95% CI: 9400–18,000) BC-related premature deaths to result from the 2010 ambient BC levels (Table 1). Given the current evidence that the effect estimate might be higher for BC compared to PM2.5 in terms of effect per µg/m3, we consider the mortality estimate based on the risk coefficient for PM2.5 as a lower-bound estimate. We estimate approximately ten times the BC-related premature deaths using the BC-specific risk estimate drawn from Janssen et al. (2011) (mean: 133,807; 95% CI: 92,259–174,523) compared to the estimate based on Krewski et al. (2009). Also we estimate approximately 75,000 deaths using the two PDFs of β generated by combining the Krewski and the Janssen risk estimates.

Using the all-cause mortality risk estimate from Krewski et al. (2009), Fann et al. (2012) estimate 130,000 PM2.5-related deaths to result from 2005 air quality level. Our estimate of BC-related deaths in 2010 based on the same risk estimate from Krewski et al. (2009) equals to about 11% of the total PM2.5-related death estimate in 2005 above. Since the observational data show that BC comprises approximately 5–10% of average urban PM2.5 mass in the US, our estimate indicates that the ratio of national BC-PM2.5 related mortality is slightly higher than the ratio of BC-PM2.5 mass concentrations. This is not surprising given that BC is a primary aerosol, with concentrations highest near urban sources, where people are also concentrated.

We also estimate 32 (95% CI: 13–52) infant deaths due to BC exposure in 2010, and a range of morbidity impacts, including nearly 20,000 hospital admissions and emergency room visits, about 30,000 cases of bronchitis (acute and chronic), and hundreds of thousands of cases of respiratory symptoms, lost work days as well as restricted-activity days.

3.4. Spatial variability in BC-related mortality estimates

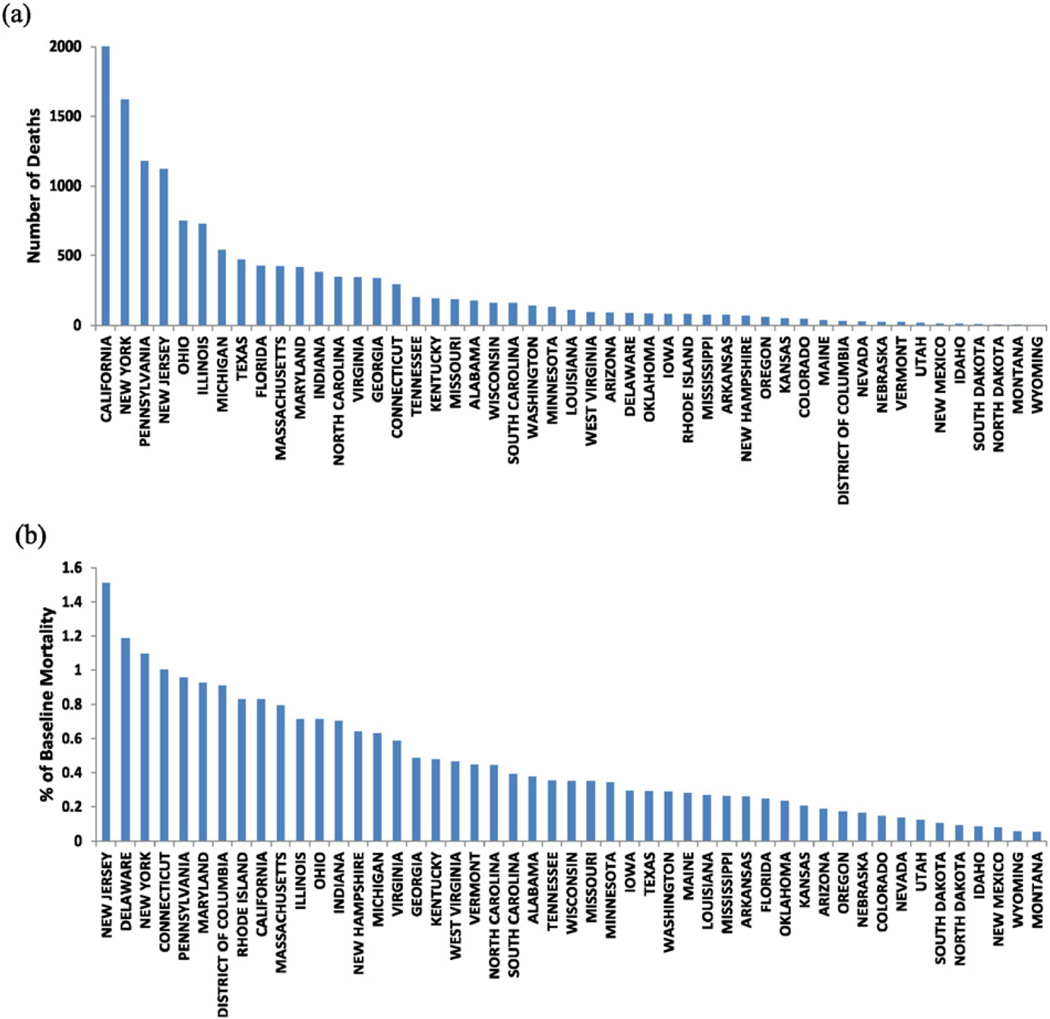

Fig. 4(a) and (b) shows the annual BC-related mortality and the percent of baseline mortality in 2010 by State, respectively, ranked from the highest values to the lowest. States are ranked differently by total number of deaths and by percent of deaths. Three States, namely, New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey are ranked among the top 5 States in both rankings (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Ranking annual BC-related mortality by State: (a) Ranked by annual number of death; (b) Ranked by percent of baseline mortality.

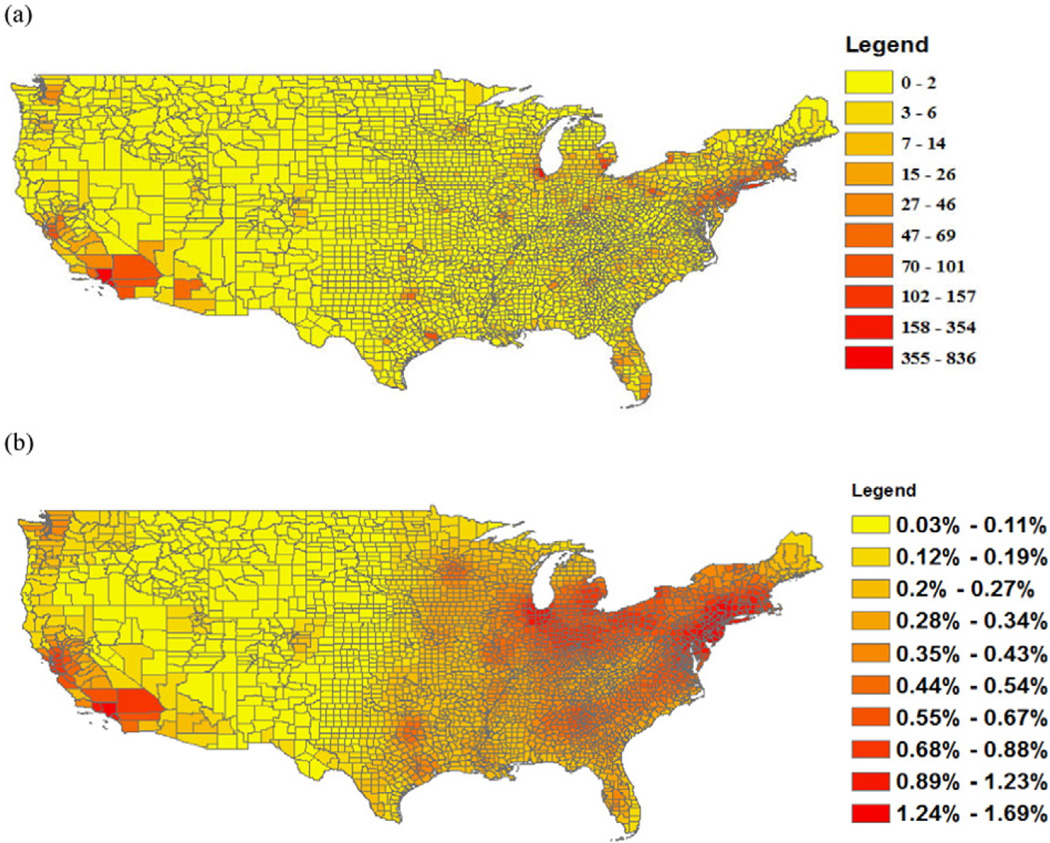

Fig. 5(a) and (b) shows the annual BC-related mortality and the percent of baseline mortality in 2010 by county, respectively. Table 2 shows the top 10 ranked counties based on total BC-related deaths versus percent of deaths. Two counties, i.e. Bergen county, NJ and Westchester county, NY are listed among the top 10 counties in both rankings. The top 10 counties ranked based on percent of deaths are all located in the States of New Jersey or New York and surrounding NYC.

Fig. 5.

Spatial distribution of annual BC-related mortality at the county level: (a) Number of deaths; and (b) Percent of baseline mortality.

Table 2.

Top 10 ranked counties based on the number of BC-related deaths versus percent of deaths.

| Rank | State | County | Largest city | Number of death | State | County | Largest city | % of deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CA | Los Angeles | Los Angeles | 836 | NJ | Bergen | NYC Metro | 1.695% |

| 2 | IL | Cook | Chicago | 354 | NJ | Passaic | NYC Metro | 1.689% |

| 3 | NY | Queens | Queens | 247 | NY | Rockland | NYC Metro | 1.684% |

| 4 | NY | Kings | Brooklyn | 232 | NY | Bronx | Bronx | 1.674% |

| 5 | CA | Orange | Los Angeles | 220 | NY | Westchester | Yonkers | 1.634% |

| 6 | PA | Philadelphia | Philadelphia | 157 | NJ | Somerset | NYC Metro | 1.615% |

| 7 | NJ | Bergen | NYC Metro | 155 | NJ | Mercer | Philadelphia Metro | 1.612% |

| 8 | NY | Nassau | Long Island | 145 | NY | New York | Manhattan | 1.612% |

| 9 | MI | Wayne | Detroit | 142 | NJ | Morris | NYC Metro | 1.600% |

| 10 | NY | Westchester | Yonkers | 132 | NJ | Essex | Newark | 1.587% |

3.5. Uncertainty analysis

Uncertainties exist in every component of the health impact assessment, including the concentration–response coefficients, the simulated pollutant concentrations, the population and the baseline incidence rates. A significant source of uncertainty derives from published estimates of concentration–response coefficient, β which we have already taken into account in estimating the national BC-related mortality and morbidity. The wide confidence intervals around the mean estimates of mortality of morbidity show the considerable uncertainty in these estimates (Table 1). Also, the uncertainty associated with the species potency of BC can significantly affect the estimates of BC-related health outcomes. As indicated in Table 1, if we apply a BC-specific risk coefficient, the national total BC-related mortality estimate could be up to ten times larger than the estimate based on PM2.5-related risk coefficient. On the other hand, BC-related health impact estimates are also highly sensitive to the assumptions about exposure to ambient BC, which is represented using air quality model output here. In order to investigate how the uncertainty in annual average BC concentrations might alter our best estimate of national BC-related mortality, we repeat our calculation by increasing the BC concentrations by 10%, 20%, 30%, 40% and 50%, and also decreasing the concentrations by the same percentages. The results indicate that the changes in mortality estimate are nearly 100% linearly related to the changes in BC concentrations over the range of BC concentrations relevant to health impact assessments in the US.

Some degree of uncertainty is also associated with air quality model resolution. In this study, we use a global model with a horizontal resolution of approximately 55 km, which is a relatively coarse resolution compared with some regional air quality models, such as the Community Multiscale Air Quality (CMAQ) model that runs with 12 km and 36 km resolutions. Punger and West (2013) examined how estimates of mortality in the US attributable to PM2.5 at coarse resolutions differ from those at the finest resolution (12 km). They report that coarse grid resolutions produce mortality estimates that are biased low for PM2.5, particularly for primary PM2.5 species. More specifically, their analyses show that at the resolution of 55 km that is used in this study, the estimate of mortality attributable to BC was approximately 15% lower than the 12-km resolution estimate. If we apply the bias identified by Punger and West (2013) here, the estimates of national BC-related mortality in this study could be increased by about 15%. This indicates that our estimates of health benefits associated with BC mitigation might be conservative. In contrast, from the comparison of the simulated to observed concentrations (See Fig. 2), the model may overestimate current BC concentrations in the North East and California, hence some cancelation of error owing to emissions and downscaling may be expected.

Overall, we consider the value of concentration–response coefficient contributes the most to the uncertainty in the estimated health outcomes related to BC exposure, particularly premature mortality. Thus, reducing uncertainty in this input variable would substantially reduce the uncertainty in the estimated mortality attributable BC.

4. Conclusions

Using the all-cause mortality risk estimate for PM2.5 from Krewski et al. (2009), we estimate that 13,910 (95% CI: 9419–18,391) deaths to result from anthropogenic BC emissions in 2010. These deaths account for approximately 0.6% (95% CI: 0.4%–0.8%) of the national deaths occurring in the US in 2010. Using morbidity risk estimates for PM2.5 drawn from epidemiological studies, we also estimate hundreds of thousands of cases of BC-related illnesses, such as hospital admissions, emergency room visits, bronchitis, and respiratory symptoms.

These health impact estimates are highly sensitive to the assumptions about the risk estimates drawn from published epidemiological studies. Given recent evidence that BC particles may pose a greater risk on human heath than other components of PM2.5, we conducted a comprehensive literature review of existing epidemiological studies that report the health effects of both total PM2.5 mass and BC particles in a single study. Our review indicates that there is supporting evidence that BC may be more harmful that other constitutes of PM2.5 and the PM2.5 mass as a whole, but there are also limitations of existing studies to differentiate the health effects of various constituents of PM2.5. Based on our review, we performed sensitivity analysis of the national BC-related mortality using a BC-specific risk estimate from a recent review and meta-analysis of the health effects of BC by Janssen et al. (2011). Using the latter risk estimate, we estimate 133,807 (95% CI: 92,259– 174,523) BC-related mortality, which is approximately ten time larger than the mortality estimate based on Krewski et al. (2009).

To our best knowledge, this is the first study of its kind that assesses the public health burden of ambient BC at the national, state and county level in the US. Earlier studies focus on the health impacts of total PM mass other than different constituents of PM. A recent study conducted by the U.S. EPA (Fann et al., 2012) estimate 130,000 PM2.5-related deaths to result from 2005 ambient PM2.5 levels in the US based on the same risk estimate drawn from Krewski et al. (2009) used in this study. Therefore, our estimate of BC-related deaths accounts for approximately 11% of the total PM2.5-related deaths. We consider this as a lower bound estimate. When the BC-related mortality is calculated using the risk estimate for BC drawn from Janssen et al. (2011), it could account for up to 100% of the total PM2.5 estimate. The uncertainty associated with the concentration–response coefficients of BC might be reduced in future health impact assessments as epidemiological studies focusing on the exclusive long-term health effects of exposure to BC become available.

Despite the uncertainties in our estimates, our findings indicate that controlling BC emissions would have substantial benefits for public health in the US, as indicated by avoided premature deaths and illnesses. Furthermore, our analysis of the spatial variations in BC-related mortality show that the metropolitan areas of Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia and Detroit are the locations with the greatest numbers of BC-related mortality, and the metropolitan areas of New York City, Philadelphia and Newark are the locations with the greatest percentages of BC-related mortality. Therefore, further investigations of BC emissions, air quality and control measures in these metropolitan areas are warranted.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Black carbon (BC) is a strong climate warming forcing agent.

This study quantifies the public health burden attributed to BC exposure in the US.

We use an integrated assessment approach to estimate BC-related health impacts.

Our findings suggest substantial health benefits to be resulted from BC control.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through the NASA applied Sciences Program grant NNX09AN77G. Dr. Ying Li was partially supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Earth Institute at Columbia University. Dr. Patrick Kinney was partially supported by NIEHS Center grant # P30 ES009089.

Appendix A

Table A.I.

Summary of concentration–response (C–R) coefficients of mortality related to long-term exposure to PM2.5 and BC.

| Reference | Health endpoint (mortality) |

Location and study group | C–R coefficient per 1-µg/m3 |

BC/PM2.5 effect ratio |

Coefficient of the correlation between PM2.5 and BC |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 | BC | |||||

| Janssen et al. (2011) | All-cause | Meta-analysis, including 4 studies: 2 in the US, 1 in France and 1 in Netherlands2 |

0.007 | 0.058 | 8.4 | N/A |

| Smith et al. (2010) | All-cause | 66 US cities, American Cancer Society cohort, age > 30 | 0.006 | 0.058 | 9.8 | N/A |

| Cardiopulmonary | 0.012 | 0.104 | 8.7 | |||

| Lipfert et al. (2006) | All-cause | 70,000 male, US veterans cohort | 0.006 | 0.166 | 27.7 | 0.54 |

| Beelen et al. (2008) | Natural-cause | 120,852 adults aged 55–69; The Netherlands, | 0.006 | 0.049 | 8.2 | 0.82 |

| Respiratory | 0.007 | 0.182 | 26.1 | |||

| Cardiovascular | 0.004 | 0.039 | 9.8 | |||

| Filleul et al. (2005) | Natural-cause | 14,284 adults, age 25–59, France | 0.010 | 0.058 | 5.9 | 0.87 |

| Cardiopulmonary | 0.012 | 0.049 | 4.1 | |||

| Ostro et al. (2010) | All-cause | 133,479 female school teachers, California | 0.077 | 0.486 | 6.3 | 0.84 |

| Cardiopulmonary | 0.091 | 0.523 | 5.8 | |||

| Gan et al., (2011) | Coronary heart disease | 452,735 residents, 45–85 years of age in Vancouver, Canada | 0.013 | 0.039 | 3 | 0.13 |

These four studies are also listed in this Table: Smith et al., 2010; Lipfert et al., 2006; Beelen et al., 2008; Filleul et al., 2005. The concentration–response coefficients of these four studies were converted from the Relative Risks listed in Table 2 in Janssen et al. (2012) rather than drawn directly from the original papers.

Table A.II.

Summary of concentration–response (C–R) coefficients of mortality and morbidity related to short-term exposure to PM2.5 and BC.

| Reference | Health endpoint | Location and study group | C-R coefficient per 1-µg/m3 |

BC/PM2.5 effect ratio |

Coefficient of the correlation between PM2.5 and BC |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 | BC | |||||

| Levy et al. (2012) | Meta-analysis: daily all-cause mortality |

Including 8 studies: 5 in the US, 2 in UK and 1 in Canada |

0.0012 | 0.0004 | 0.33 | N/A |

| Klemm et al., (2004) | Daily all-cause mortality, age > 65 |

Atlanta | 0.00398 | 0.01024 | 2.6 | N/A |

| Ostro et al. (2007) | Daily CVD mortality | Six California counties | 0.0011 | 0.026 | 23.9 | 0.53 |

| Ito et al. (2010) | Daily CVD mortality | New York City | 0.002 (warm season) | 0.037 (warm season), | 18.5 (warm season), | 0.6 (warm season), |

| 0.001 (cold season) | 0.026 (cold season) | 26 (cold season) | 0.72 (cold season) | |||

| Daily CVD | New York City | N/A (warm season), | 0.023 (warm season), | 22 (cold season) | ||

| hospitalization | 0.0011 (cold season) | 0.024 (cold season) | ||||

| Metzger et al. (2004) | Daily CVD emergency department visits |

Atlanta | 0.0032 | 0.02 | 6.1 | 0.61 |

| Zanobetti and Schwartz (2006) | Daily CVD hospital admissions |

Boston | 0.0053 | 0.049 | 9.3 | 0.66 |

| Wang et al. (2013) | Emergency-room visits |

Shanghai, China | 0.00045 | 0.0049 | 11.1 | 0.67 |

| Hua et al. (2014) | Children asthma admissions |

Shanghai, China | 0.00032 (age 0–4), | 0.016 (age 0–4), | 50 (age 0–4), | 0.80 |

| 0.0028 (age 5–14) | 0.038 (age 5–14) | 14 (age 5–14) | ||||

CVD: cardiovascular.

Table A.III.

National rates of all-cause mortality, hospital admissions and emergency room visits (per 100 people per year) by age group used in this study (Source: Abt Associates Inc., 2013(Abt Associates, 2013)).

| Health endpoints and year | Infant (<1) | 1–17 | 18–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | 75–84 | 85+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | ||||||||||

| Calculated CDC 2004–2006 average | 0.230 | 0.028 | 0.089 | 0.104 | 0.192 | 0.432 | 0.908 | 2.124 | 5.270 | 13.979 |

| 2010 ratio to the calculated 2004–2006 average | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Hospital admissions and emergency room visits | ||||||||||

| Hospital admissions – all respiratory, 2007 | 2.872 | 0.426 | 0.205 | 0.231 | 0.408 | 0.791 | 1.313 | 2.972 | 4.970 | 8.045 |

| Hospital admissions – all cardiovascular, 2007 | 0.056 | 0.017 | 0.107 | 0.164 | 0.481 | 1.221 | 2.272 | 4.681 | 7.749 | 11.583 |

| Emergency room visits for asthma, 2007 | 0.865 | 0.557 | 0.441 | 0.381 | 0.368 |

Table A.IV.

Selected acute and chronic incidence (cases/person-year) (Source: Abt Associates Inc., 2013(Abt Associates, 2013)).

| Endpoint | Age | Rate | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute bronchitis | 8–12 | 0.043 | American Lung Association | |

| Chronic bronchitis | 27+ | 0.00378 | Abbey et al. (1993) | |

| Lower respiratory symptoms | 7–14 | 0.438 | Schwartz et al. (1994) | |

| Upper respiratory symptoms | 9–11 | 124.79 | Pope III et al. (1991) | |

| Asthma exacerbation | Cough | 8–13 | 24.46 | Ostro et al. (2001) |

| Shortness of breath | 27.74 | |||

| Wheeze | 13.51 | |||

| Work loss days | 18–64 | 2.172 | Adam et al. (1999) | |

| Minor restricted-activity days | 18–64 | 7.8 | Ostro and Rothschild (1989) |

Footnotes

In most cases, cohort studies report the spatial correlations between pollutants and time-series studies report temporal correlations.

References

- Abbey DE, Ostro BE, Petersen F, Burchette RJ. Chronic respiratory symptoms associated with estimated long-term ambient concentrations of fine particulates less than 2.5 microns in aerodynamic diameter (PM2. 5) and other air pollutants. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 1994;5:137–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abt Associates. Environmental Benefits and Mapping Program (BenMAP, Version 4.0.67) 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Anenberg SC, Horowitz LW, Tong DQ, West J. An estimate of the global burden of anthropogenic ozone and fine particulate matter on premature human mortality using atmospheric modeling. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:1189–1195. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anenberg SC, Schwartz J, Vignati E, Emberson L, Muller NZ, West JJ, et al. Global Air Quality and Health Co-benefits of Mitigating Near-term Climate Change Through Methane and Black Carbon Emission Controls. 2012 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beelen R, Hoek G, van Den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, Fischer P, Schouten LJ, et al. Long-term effects of traffic-related air pollution on mortality in a Dutch cohort (NLCS-AIR study) Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:196–202. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey I, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM, Logan JA, Field BD, Fiore AM, et al. Global modeling of tropospheric chemistry with assimilated meteorology: model description and evaluation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001;106:23073–23095. [Google Scholar]

- Bond TC, Bhardwaj E, Dong R, Jogani R, Jung S, Roden C, et al. Historical emissions of black and organic carbon aerosol from energy-related combustion, 1850–2000. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2007:21. [Google Scholar]

- Bond TC, Doherty SJ, Fahey D, Forster P, Berntsen T, DeAngelo B, et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: a scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013;118:5380–5552. [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Wang Y, McElroy M, He K, Yantosca R, Sager PL. Regional CO pollution and export in China simulated by the high-resolution nested-grid GEOS–chem model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009;9:3825–3839. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AJ, Ross Anderson H, Ostro B, Pandey KD, Krzyzanowski M, Künzli N, et al. The global burden of disease due to outdoor air pollution. J. Toxic. Environ. Health A. 2005;68:1301–1307. doi: 10.1080/15287390590936166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke W, Liousse C, Cachier H, Feichter J. Construction of a 1 × 1 fossil fuel emission data set for carbonaceous aerosol and implementation and radiative impact in the ECHAM4 model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1999;104:22137–22162. (1984–2012) [Google Scholar]

- Dockery DW, Pope CA, Xu X, Spengler JD, Ware JH, Fay ME, et al. An association between air pollution and mortality in six US cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:1753–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockery DW, Cunningham J, Damokosh AI, Neas LM, Spengler JD, Koutrakis P, et al. Health effects of acid aerosols on North American children: respiratory symptoms. Environ. Health Perspect. 1996;104:500. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Fairlie T, Jacob DJ, Park RJ. The impact of transpacific transport of mineral dust in the United States. Atmos. Environ. 2007;41:1251–1266. [Google Scholar]

- EPA. EPAUS. Report to Congress on Black Carbon. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Fann N, Lamson AD, Anenberg SC, Wesson K, Risley D, Hubbell BJ. Estimating the national public health burden associated with exposure to ambient PM2. 5 and ozone. Risk Anal. 2012;32:81–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filleul L, Rondeau V, Vandentorren S, Le Moual N, Cantagrel A, Annesi-Maesano I, et al. Twenty five year mortality and air pollution: results from the French PAARC survey. Occup. Environ. Med. 2005;62:453–460. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.014746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoukis C, Nenes A. ISORROPIA II: a computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+−Ca 2+−Mg 2+−NH 4+−Na+−SO 4 2–−NO 3–−Cl–−H 2 O aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007;7:4639–4659. [Google Scholar]

- Gan W, Koehoorn M, Davies H, Demers P, Tamburic L, Brauer M. Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and the risk of coronary heart disease hospi-talization and mortality. Epidemiology. 2011;22:S30. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglio L, Randerson J, Van der Werf G, Kasibhatla P, Collatz G, Morton D, et al. Assessing variability and long-term trends in burned area by merging multiple satellite fire products. Biogeosciences. 2010:7. [Google Scholar]

- Heald CL, Collett J, Jr, Lee T, Benedict K, Schwandner F, Li Y, et al. Atmospheric ammonia and particulate inorganic nitrogen over the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2012:12. [Google Scholar]

- Henze DK, Seinfeld JH, Shindell DT. Inverse modeling and mapping US air quality influences of inorganic PM 2.5 precursor emissions using the adjoint of GEOS– chem. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009;9:5877–5903. [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Yin Y, Peng L, Du L, Geng F, Zhu L. Acute effects of black carbon and PM2.5 on children asthma admissions: a time-series study in a Chinese city. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;481:433–438. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell BJ, Hallberg A, McCubbin DR, Post E. Health-related benefits of attaining the 8-hr ozone standard. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005:73–82. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Mathes R, Ross Z, Nádas A, Thurston G, Matte T. Fine particulate matter constituents associated with cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality in New York City. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;119:467–473. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeglé L, Quinn P, Bates T, Alexander B, Lin J-T. Global distribution of sea salt aerosols: new constraints from in situ and remote sensing observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:3137–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen N, Hoek G, Simic-Lawson M, Fischer P, van Bree L, ten Brink H, et al. Black carbon as an additional indicator of the adverse health effects of airborne particles compared with PM10 and PM2. 5. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:1691–1699. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen NA, Gerlofs-Nijland ME, Lanki T, Salonen RO, Cassee F, Hoek G, et al. Health effects of black carbon. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez J, Canagaratna M, Donahue N, Prevot A, Zhang Q, Kroll J, et al. Evolution of organic aerosols in the atmosphere. Science. 2009;326:1525–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1180353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney PL, Aggarwal M, Northridge ME, Janssen N, Shepard P. Airborne concentrations of PM (2.5) and diesel exhaust particles on Harlem sidewalks: a community-based pilot study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000;108:213. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm R, Lipfert F, Wyzga R, Gust C. Daily mortality and air pollution in Atlanta: two years of data from ARIES. Inhal. Toxicol. 2004;16:131–141. doi: 10.1080/08958370490443213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewski D, Burnett RT, Goldberg MS, Hoover K, Siemiatycki J, Jerrett M, et al. Reanalysis of the Harvard Six Cities Study and the American Cancer Society Study of Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality. Cambridge, MA: Health Effects Institute; 2000. p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Krewski D, Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Ma R, Hughes E, Shi Y, et al. Extended Follow-up and Spatial Analysis of the American Cancer Society Study Linking Particulate Air Pollution and Mortality. Res Rep Health Eff Inst. 2009:5–114. discussion 115-36) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laden F, Schwartz J, Speizer FE, Dockery DW. Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality: extended follow-up of the Harvard six cities study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006;173:667–672. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200503-443OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibensperger E, Mickley L, Jacob D, Chen W-T, Seinfeld J, Nenes A, et al. Climatic effects of 1950–2050 changes in US anthropogenic aerosols-part 1: aerosol trends and radiative forcing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012;12:3333–3348. [Google Scholar]

- Levy JI, Diez D, Dou Y, Barr CD, Dominici F. A meta-analysis and multisite time-series analysis of the differential toxicity of major fine particulate matter constituents. Am. J. Epidemiol. kwr. 2012:457. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Gibson JM, Jat P, Puggioni G, Hasan M, West JJ, et al. Burden of disease attributed to anthropogenic air pollution in the United Arab Emirates: estimates based on observed air quality data. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;408:5784–5793. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert F, Baty J, Miller J, Wyzga R. PM2. 5 constituents and related air quality variables as predictors of survival in a cohort of US military veterans. Inhal. Toxicol. 2006;18:645–657. doi: 10.1080/08958370600742946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Jacob DJ, Bey I, Yantosca RM. Constraints from 210Pb and 7Be on wet deposition and transport in a global three-dimensional chemical tracer model driven by assimilated meteorological fields. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001;106:12109–12128. (1984–2012) [Google Scholar]

- Malm WC, Sisler JF, Huffman D, Eldred RA, Cahill TA. Spatial and seasonal trends in particle concentration and optical extinction in the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1994;99:1347–1370. (1984–2012) [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Li Q, Zhang L, Chen Y, Randerson J, Chen D, et al. Biomass burning contribution to black carbon in the Western United States Mountain Ranges. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:11253–11266. [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Li Q, Randerson J, Chen D, Zhang L, Hao W, et al. Top-down estimates of biomass burning emissions of black carbon in the Western United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2013:13. [Google Scholar]

- Mar TF, Koenig JQ, Primomo J. Associations between asthma emergency visits and particulate matter sources, including diesel emissions from stationary generators in Tacoma, Washington. Inhal. Toxicol. 2010;22:445–448. doi: 10.3109/08958370903575774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger KB, Tolbert PE, Klein M, Peel JL, Flanders WD, Todd K, et al. Ambient air pollution and cardiovascular emergency department visits. Epidemiology. 2004;15:46–56. doi: 10.1097/01.EDE.0000101748.28283.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D, Chow J, Leibensperger E, Malm W, Pitchford M, Schichtel B, et al. Decreases in elemental carbon and fine particle mass in the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:4679–4686. [Google Scholar]

- Ostro BD. Air pollution and morbidity revisited: a specification test. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1987;14:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B. Outdoor air Pollution. WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Ostro BD, Rothschild S. Air pollution and acute respiratory morbidity: an observational study of multiple pollutants. Environ. Res. 1989;50:238–247. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(89)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B, Lipsett M, Mann J, Braxton-Owens H, White M. Air pollution and exacerbation of asthma in African-American children in Los Angeles. Epidemiology. 2001;12:200–208. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200103000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B, Feng W-Y, Broadwin R, Green S, Lipsett M. The effects of components of fine particulate air pollution on mortality in California: results from CALFINE. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007:13–19. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostro B, Lipsett M, Reynolds P, Goldberg D, Hertz A, Garcia C, et al. Long-term exposure to constituents of fine particulate air pollution and mortality: results from the California Teachers Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010;118:363. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901181. (Online) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park RJ, Jacob DJ, Chin M, Martin RV. Sources of carbonaceous aerosols over the United States and implications for natural visibility. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003:108. 1984a. [Google Scholar]

- Park RJ, Jacob DJ, Field BD, Yantosca RM, Chin M. Natural and transboundary pollution influences on sulfate-nitrate-ammonium aerosols in the United States: implications for policy. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2004:109. 1984b. [Google Scholar]

- Park RJ, Jacob DJ, Kumar N, Yantosca RM. Regional visibility statistics in the United States: natural and transboundary pollution influences, and implications for the Regional Haze Rule. Atmos. Environ. 2006;40:5405–5423. [Google Scholar]

- Peng RD, Bell ML, Geyh AS, McDermott A, Zeger SL, Samet JM, et al. Emergency admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and the chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009;117:957–963. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, III, Dockery DW, Spengler JD, Raizenne ME. Respiratory health and PM10 pollution: a daily time series analysis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1991;144:668–674. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.3_Pt_1.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, III, Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, Dockery DW, Evans JS, Speizer FE, et al. Particulate air pollution as a predictor of mortality in a prospective study of US adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995;151:669–674. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_Pt_1.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA, III, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D, Ito K, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA. 2002;287:1132–1141. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.9.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punger EM, West JJ. The effect of grid resolution on estimates of the burden of ozone and fine particulate matter on premature mortality in the USA. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 2013;6:563–573. doi: 10.1007/s11869-013-0197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pye H, Liao H, Wu S, Mickley LJ, Jacob DJ, Henze DK, et al. Effect of changes in climate and emissions on future sulfate–nitrate–ammonium aerosol levels in the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2009:1984–2012. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Reche C, Querol X, Alastuey A, Viana M, Pey J, Moreno T, et al. New considerations for PM, black carbon and particle number concentration for air quality monitoring across different European cities. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011;11:6207–6227. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J, Neas LM. Fine particles are more strongly associated than coarse particles with acute respiratory health effects in schoolchildren. Epidemiology. 2000;11:6–10. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200001000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Jerrett M, Anderson HR, Burnett RT, Stone V, Derwent R, et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: health implications of short-lived greenhouse pollutants. Lancet. 2010;374:2091–2103. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61716-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Werf GR, Randerson JT, Giglio L, Collatz GJ, Kasibhatla PS, Arellano A., Jr Interannual variability in global biomass burning emissions from 1997 to 2004. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006;6:3423–3441. [Google Scholar]

- van der Werf GR, Randerson JT, Giglio L, Collatz G, Mu M, Kasibhatla PS, et al. Global fire emissions and the contribution of deforestation, savanna, forest, agricultural, and peat fires (1997–2009) Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010;10:11707–11735. [Google Scholar]

- Walker J, Philip S, Martin R, Seinfeld J. Simulation of nitrate, sulfate, and ammonium aerosols over the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012;12:11213–11227. [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, McElroy MB, Jacob DJ, Yantosca RM. A nested grid formulation for chemical transport over Asia: applications to CO. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2004;109:D22307. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Chen R, Meng X, Geng F, Wang C, Kan H. Associations between fine particle, coarse particle, black carbon and hospital visits in a Chinese city. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;458:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesely M. Parameterization of surface resistances to gaseous dry deposition in regional-scale numerical models. Atmos. Environ. 1989;23:1293–1304. (1967) [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff TJ, Grillo J, Schoendorf KC. The relationship between selected causes of postneonatal infant mortality and particulate air pollution in the United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 1997;105:608. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A, Schwartz J. Air pollution and emergency admissions in Boston, MA. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2006;60:890–895. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanobetti A, Franklin M, Koutrakis P, Schwartz J. Fine particulate air pollution and its components in association with cause-specific emergency admissions. Environ. Heal. 2009;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Jacob DJ, Knipping EM, Kumar N, Munger J, Carouge C, et al. Nitrogen deposition to the United States: distribution, sources, and processes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2012;12:241–282. [Google Scholar]