Abstract

Background

Paenibacillus sp. strain VT-400, a novel spore-forming bacterium, was isolated from patients with hematological malignancies.

Methods

Paenibacillus sp. strain VT-400 was isolated from the saliva of four children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The genome was annotated using RAST and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline to characterize features of antibiotic resistance and virulence factors. Susceptibility to antibiotics was determined by the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method. We used a mouse model of pneumonia to study virulence in vivo. Mice were challenged with 7.5 log10–9.5 log10 CFU, and survival was monitored over 7 days. Bacterial load was measured in the lungs and spleen of surviving mice 48 h post-infection to reveal bacterial invasion and dissemination.

Results

Whole-genome sequencing revealed a large number of virulence factors such as hemolysin D and CD4+ T cell-stimulating antigen. Furthermore, the strain harbors numerous antibiotic resistance genes, including small multidrug resistance proteins, which have never been previously found in the Paenibacillus genus. We then compared the presence of antibiotic resistance genes against results from antibiotic susceptibility testing. Paenibacillus sp. strain VT-400 was found to be resistant to macrolides such as erythromycin and azithromycin, as well as to chloramphenicol and trimethoprim–sulphamethoxazole. Finally, the isolate caused mortality in mice infected with ≥8.5 log10 CFU.

Conclusions

Based on our results and on the available literature, there is yet no strong evidence that shows Paenibacillus species as an opportunistic pathogen in immunocompromised patients. However, the presence of spore-forming bacteria with virulence and antibiotic resistance genes in such patients warrants special attention because infections caused by spore-forming bacteria are poorly treatable.

Keywords: Paenibacillus sp., Antibiotic resistance, Nosocomial, Hematological malignancies, Immunocompromised, Pneumonia, Pathogen

Background

Acute leukemia accounts for more than 10,000 deaths annually despite improved treatment regimens and novel cytostatic agents [1]. Pneumonia due to opportunistic Gram-positive Staphylococcus spp., Bacillus spp., and Enterococcus spp. is one of the leading causes of morbidity in these patients, as well as in patients with other forms of hematological malignancies, because of treatment-induced immunosuppression [2, 3].

The oral cavity, which hosts more than 700 commensal bacterial species, is the main reservoir of microorganisms that cause aspiration pneumonia [4, 5]. Thus, investigating the oral microbiome is essential to improve therapeutic strategies, especially for patients with hematological malignancies [6]. However, most commensal bacteria are not yet culturable, and molecular techniques based on cloning and sequencing the ribosomal 16S RNA have been used instead to identify species in the human microbiome [7]. Nevertheless, these techniques are prone to false negatives, such as when one bacterial species masks another, and thus underestimate bacterial diversity [8, 9]. In a previous study, we described Paenibacillus sp. strain VT-400, a novel spore-forming bacterium isolated from the saliva of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia [10]. The strain has never been previously detected in humans.

Notably, spore-forming bacteria are poorly studied, and only a few such bacteria have been described and are associated with the human microbiota [11, 12]. Spores tolerate high temperature, radiation, and noxious chemicals, harbor genes that confer antibiotic resistance, and allow bacteria to survive in unfavorable conditions [13, 14]. Thus, spores contribute significantly to the persistence of infection and the spread of antimicrobial resistance [15]. Indeed, prophylactic treatments like oral rinses are poorly effective against spores, and are thus not sufficiently reduce the bacterial load in the oropharynx, or prevent aspiration pneumonia in at-risk patients, especially those with underlying pathologies such as hematological malignancies [16, 17]. Therefore, identification and characterization of potentially infectious spore-forming microbial species are critical to improve the management or treatment of patients with acute leukemia.

Paenibacillus spp. was not known to cause human disease until recent reports implicated P. alvei, P. thiaminolyticus, and P. sputi in respiratory and urinary tract infection, as well as bacteremia in a patient on hemodialysis [18–20]. In this study, we describe Paenibacillus sp. strain VT-400, a novel bacterium isolated from the saliva of four children with hematological malignancies, and investigate its potential to cause pneumonia.

Methods

Bacterial strain

Paenibacillus sp. strain VT-400 was isolated from the saliva of four children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who were hospitalized at First Pavlov State Medical University, St. Petersburg, Russia. Unless stated otherwise, the isolate was grown on Columbia agar with 5 % sheep blood (BioMerieux, France) and were stored at −80 °C in Columbia broth (BioMerieux) supplemented with 50 % glycerol. The strain was screened for hemolytic activity by cultivation at 37 °C for 48 h on agar plates supplemented with 5 % sheep blood. Clearing and greenish zones around colonies were considered to indicate β- and α-hemolytic activity, respectively. Primary morphological characterization was performed by light microscopy (Axiostar, Zeiss, Germany), and Gram staining was performed using a kit (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

To generate inoculum for infecting mice, the strain was grown at 37 °C for 48 h on Columbia agar with 5 % sheep blood. Colonies picked from the plate were then grown for 18 h at 37 °C in 5 mL Columbia broth. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000×g for 15 min (Eppendorf 5415 C centrifuge; Eppendorf Geratgebau GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), and suspended in an isotonic phosphate buffer (0.15 mM, pH 7.2). The turbidity of the suspension was adjusted using a McFarland standard.

Genome annotation and phylogenetic analysis

Whole-genome sequences from isolates of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT-400 were aligned using MUSCLE, and phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the Tamura-Nei distance model in PHYML version 3.0, with 1000 bootstrap replicates [21–23]. The most closely related Paenibacillus genomes were included in the analysis. The genome was annotated and mined for virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes using Rapid Annotation using Subsystems Technology (RAST) and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline [24, 25].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Susceptibility to antibiotics was determined by the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method according to criteria defined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [26]. The strain was tested for susceptibility to 30 µg amoxiclav, 10 μg ampicillin, 10 U penicillin, 30 µg vancomycin, 30 μg cefotaxime, 10 μg erythromycin, 15 μg azithromycin, 10 µg gentamicin, 30 µg amikacin, 30 μg kanamycin, 2 μg clindamycin, 30 μg doxycycline, 5 µg ciprofloxacin, 30 μg neomycin, 30 μg chloramphenicol, 30 μg tetracycline (Becton–Dickinson, USA) and 1.25 μg/23.75 μg trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Oxoid, UK).

Pathogenicity in a mouse infection model

Adult C57BL/6 mice weighing approximately 20 g (Rappolovo, North-West region, Russia) were housed in individual cages in a facility free of known murine pathogens, and were provided feeding ad libitum. Animals were cared for in accordance with National Research Council recommendations, and experiments were executed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [27].

Animals were randomly designated into two groups of eight, which were used to measure overall survival and bacterial load. Mice were then anesthetized with 2 % isoflurane, and orally instilled with bacterial suspension as previously described [28]. Briefly, nares were blocked, and mice aspirated 50 µL Paenibacillus sp. strain VT400 into the lungs while being held vertically for 60 s. Mice received a total dose of 7.5 log10, 8.5 log10, or 9.5 log10 CFU/mouse. Control mice were treated with sterile 50 µL phosphate-buffered saline. Overall survival was assessed over 7 days, while bacterial load was measured in the lungs and spleen of surviving mice 48 h post infection.

Microbiological assessment of infected lung and spleen

Bacterial load in the spleen and lungs was measured 48 h post infection. Briefly, surviving animals in groups designated for this assessment were euthanized by CO2 and cervical dislocation. Lungs and spleen were collected and homogenized in 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline. As Paenibacillus sp. strain VT-400 was found to be resistant to chloramphenicol and trimethoprim, serial tenfold dilutions of tissue homogenates were plated on Columbia agar with 5 % sheep blood, 5 μg/mL chloramphenicol, and 10 μg/mL trimethoprim (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA), and cultured at 37 °C. Colonies of spore-forming bacteria were counted after 48 h, and bacterial loads are reported as mean log10 CFU/g tissue ± SD. Morphology was characterized by light microscopy (Axiostar, Zeiss), and cells were Gram stained using a kit (Merck).

Ethical approval and consent

Ethical approval was granted by the First State I. P. Pavlov Medical University Ethics Committee (501/M2013). In accordance with ethical approval, consent to use human biological material was assumed following completion of consent forms.

Statistics

Survival was compared by Kaplan–Meier analysis log-rank test. Differences in bacterial load were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance in SigmaStat version 2.03 (SPSS, Inc., San Rafael, CA). A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Phylogenetic analysis

Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400, which has never been detected in humans before, was isolated for the first time from the saliva of pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In a previous study, whole-genome sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq 2500, with 125-fold average coverage [10]. Assembly generated 116 contigs spanning 6,986,122 bp, with G+C content 45.8 %.

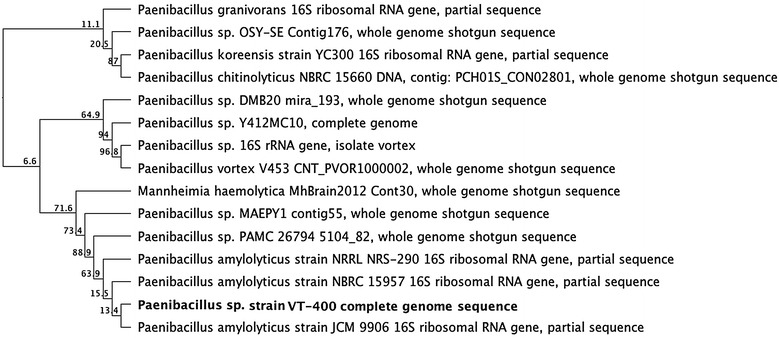

On the basis of these analyses, the strain was identified as a novel species for which Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 was assigned, and its genome was deposited in GenBank under accession number LELF01000000. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA demonstrated that Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 is clearly distinguished from other species, as well as from other strains of P. amylolyticus (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Dendrogram illustrating the relationship of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 to the most closely related Paenibacillus sequences deposited in GenBank. The tree is based on partial 16S rRNA sequences >1400 bp. Bootstrap proportions in 1000 replicates are shown at branch points

Microbiological characteristics of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400

Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 is Gram-positive, aerobic, spore-forming, rod-shaped, and motile via peritrichous flagella [10]. Colonies growing on sheep blood agar are smooth, white pearl in color, and from 0.5 to 1 mm in diameter after 24 h at 37 °C in an aerobic atmosphere. β-hemolysis was observed around colonies growing on blood agar plates. The type strain is deposited in the Deutsche Sammlung fur Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany) under accession number DSM 100755.

Genes encoding virulence factors and in vivo pathogenicity

Analysis of the genome revealed a large number of genes encoding virulence factors that may contribute to pathogenicity (Table 1) [29]. Most are degradative enzymes and adhesins that may facilitate infection, including proteases, phospholipases, ureases, chitinases, and endopeptidases [30]. Significantly, we found chemotaxis proteins that were previously shown to contribute to bacterial virulence [31]. A couple of toxins or putative toxins were also detected, as well as superantigen CD4+ T-cell-stimulating antigen, which causes severe symptoms and septic shock [32].

Table 1.

Genes encoding virulence factors in Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400

| CDS no. | Functional annotation | CDS no. | Functional annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxins or putative toxins | |||

| WP_017689222.1 | Hemolysin D | WP_047842244.1 | CD4+ T-cell-stimulating antigen |

| Degradative enzymes and adhesins | |||

| WP_047843127.1 | Cell adhesion protein | WP_047843815.1 | Peptidase M28 |

| WP_047841133.1 | Clp protease ClpX | WP_047844415.1 | Peptidase M15 |

| WP_047841161.1 | CAAX protease | WP_047840296.1 | Peptidase S9 |

| WP_047841788.1 | Zn-dependent protease | WP_047840642.1 | Peptidase S41 |

| WP_036605888.1 | Lon protease | WP_047840884.1 | Peptidase T |

| WP_047841635.1 | ATP-dependent protease | WP_047841004.1 | Peptidase C60 |

| WP_047842474.1 | Clp protease ATPase | WP_047842822.1 | Peptidase S8 |

| WP_047842474.1 | RIP metalloprotease RseP | WP_047843693.1 | Peptidase M20 |

| WP_047843793.1 | Zinc metalloprotease | WP_047841259.1 | Peptidase M4 |

| WP_047843449.1 | Alkaline serine protease | WP_047841848.1 | Peptidase C15 |

| WP_036611272.1 | O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase | WP_047844159.1 | Peptidase M22 |

| WP_047842657.1 | Oligoendopeptidase F | WP_047842036.1 | Peptidase A24 |

| WP_047842959.1 | Endoglucanase | WP_047842221.1 | Peptidase M56 |

| WP_047841916.1 | Chitinase | WP_047842221.1 | Oligopeptidase PepB |

| WP_047840281.1 | Aminopeptidase | WP_047842554.1 | Peptidase E |

| WP_047840267.1 | Methionine aminopeptidase | WP_047843428.1 | Peptidase M32 |

| WP_047844227.1 | Lysophospholipase | WP_047843333.1 | Peptidase M29 |

| WP_047843070.1 | Phospholipase D | WP_047843711.1 | Peptidase M1 |

| WP_047843459.1 | 5′-Nucleotidase | WP_047843711.1 | Peptidase M16 |

| WP_047841534.1 | GDSL family lipase | WP_036610857.1 | Urease subunit alpha ureC |

| WP_047842732.1 | d-alanyl-d-alanine carboxypeptidase | WP_047842024.1 | Urease subunit beta ureB |

| Flagella components | |||

| WP_036607291.1 | Flagellar motor protein MotA | WP_047842476.1 | Flagellar motor switch protein FliG |

| WP_036607292.1 | Flagellar motor protein MotB | WP_047842475.1 | Flagellar M-ring protein FliF |

| WP_047842487.1 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FlhA | WP_047840678.1 | Flagellar synthesis anti-sigma-D factor |

| WP_047842482.1 | Flagellar basal body rod protein FlgG | WP_047840677.1 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FlgN |

| WP_047843392.1 | Flagellar basal body P-ring biosynthesis protein FlgA | WP_047840676.1 | Flagellar hook protein FlgK |

| WP_047842488.1 | Flagellar GTP-binding protein | WP_047840675.1 | Flagellar hook protein FlgL |

| WP_047842486.1 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FlhB | WP_047840661.1 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FliS |

| WP_047842485.1 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FliQ | WP_036609359.1 | Flagellar motor switch protein FliM |

| Chemotaxis | |||

| WP_047841047.1 | Chemotaxis protein CheY | WP_036605799.1 | Chemotaxis protein CheC |

| WP_047842491.1 | Chemotaxis protein CheA | WP_036606984.1 | Chemotaxis protein CheR |

| WP_025703561.1 | Chemotaxis protein CheW | WP_017689162.1 | Chemotaxis protein CheD |

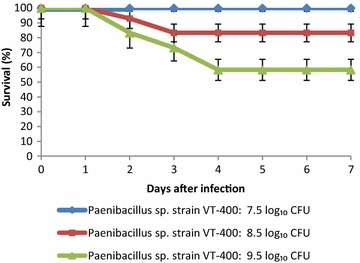

We used a mouse model of pneumonia to study virulence in vivo. Mice were challenged with 7.5 log10–9.5 log10 CFU, and survival was monitored over 7 days (Fig. 2). All animals exhibited typical signs of acute infection within 24 h, including hypothermia, piloerection, breathing difficulty, narrowed palpebral fissures, trembling, and reduced locomotor activity. There was a direct correlation between severity of symptoms and dose. Accordingly, mortality depended on dose as well, with mortality observed within 48 h in mice exposed to 8.5 log10 and 9.5 log10 CFU Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400.

Fig. 2.

Seven-day survival (%) in mice challenged with 7.5 log10, 8.5 log10, and 9.5 log10 CFU of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400. Curves are representative of three independent experiments, with n = 8 in each treatment

Bacterial load was also measured in the lungs and spleen of surviving mice 48 h post infection (Table 2). To confirm the presence of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400, tissues were homogenized and plated on selective media. Spore-forming bacteria were identified by microscopy. There was approximately 2.47 log10 more CFU/g of infected lung tissue in the high-dose group than in the low-dose group (P < 0.05). In addition, the data indicated that Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 spread from the lungs to the spleen, in which bacterial load was also dose-dependent. Taken together, the data suggest that mortality is due to, at least in part, progressive bacterial invasion and dissemination.

Table 2.

Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 CFU in the lungs and spleen 48 h post infection

| Dose (log10 CFU/mouse) | Log10 CFU/g tissue, mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Lung | Spleen | |

| Control | 0 | 0 |

| 7.5 | 0.58 ± 0.28 | 0.14 ± 0.25 |

| 8.5 | 1.13 ± 0.55 | 0.25 ± 0.18 |

| 9.5 | 3.05 ± 0.74 | 1.20 ± 0.34 |

Moreover, analysis of the Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 genome revealed an array of proteins involved in or essential for sporulation (Table 3). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that these genes are conserved and are closely related to other members of the Bacillaceae family [33].

Table 3.

Sporulation factors in the Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 genome

| CDS no. | Functional annotation |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 (pre-septation) | |

| WP_017691423.1 | Sporulation protein J |

| WP_047842196.1 | Sporulation protein M |

| Stage II (post-septation) | |

| WP_047843799.1 | Stage II sporulation protein P |

| WP_047840704.1 | Stage II sporulation protein R |

| WP_017687629.1 | Stage II sporulation protein M |

| Stage III (engulfment) | |

| WP_024632710.1 | Stage III sporulation protein D |

| WP_036674989.1 | Stage III sporulation protein AA |

| WP_036614389.1 | Stage III sporulation protein AB |

| WP_036614387.1 | Stage III sporulation protein AE |

| WP_017687241.1 | Sporulation protein YqfC |

| Stage IV (cortex) | |

| WP_036607700.1 | Stage IV sporulation protein A |

| Stage V (spore coat) | |

| WP_047844446.1 | Stage V sporulation protein AC |

| WP_047843814.1 | Stage V sporulation protein AEB |

| WP_047843753.1 | Stage V sporulation protein D |

| WP_019424875.1 | Stage V sporulation protein M |

| WP_017689559.1 | Stage V sporulation protein S |

| WP_036606123.1 | Stage V sporulation protein T |

| Other sporulation proteins | |

| WP_036607856.1 | Sporulation sigma factor SigF |

| WP_017687309.1 | Sporulation sigma factor SigG |

Analysis of drug resistance genes and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Genome analysis also revealed that Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 harbors different antibiotic resistance genes (Table 4). A total of 96 genes were major facilitator superfamily (MFS) plasma membrane transporters, 18 were multidrug ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters [34, 35]. Four genes were identified as multidrug ABC transporter permeases, eight as multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MatE) transporters, and two as small multidrug resistance (SMR) proteins [36, 37]. A multidrug drug metabolite transporter (DMT) was also detected [38]. Moreover, the Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 genome also contains genes that confer resistance to specific antibiotics. Finally, genes encoding resistance to tellurium, tunicamycin, and bleomycin were also present. These compounds are used to treat hematological malignancies [39, 40].

Table 4.

Key antibiotic resistance genes in the Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 genome

| CDS no. | Function | CDS no. | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

|

WP_047841924.1 WP_047840904.1 |

Fosmidomycin resistance protein | WP_047844309.1 | Multidrug DMT transporter |

| WP_047840644.1 | Vancomycin resistance protein | WP_047844296.1 | Multidrug MFS transporter |

| WP_047842579.1 | Tunicamycin resistance protein | WP_047841225.1 | Multidrug ABC transporter ATPase |

| WP_047840788.1 | Bleomycin resistance protein | WP_047840722.1 | Multidrug resistance protein SMR |

| WP_036607427.1 | Fosfomycin resistance protein FosB | WP_047840931.1 | Bacteriocin ABC transporter ATPase |

| WP_047841800.1 | Tellurium resistance protein TerA | WP_047844233.1 | Multidrug transporter MatE |

| WP_047840921.1 | Tellurium resistance protein TerF |

WP_047844301.1 WP_047843841.1 WP_047843528.1 |

Beta-lactamases |

| WP_026080972.1 | Macrolide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | WP_047842226.1 | Metal-dependent hydrolase, beta-lactamase superfamily II |

| WP_036615192.1 | Macrolide transporter | WP_047842143.1 | Aminoglycoside phosphotransferase |

| WP_047840666.1 | Cephalosporin hydroxylase | WP_036670493.1 | Aminoglycoside adenylyltransferase |

| WP_047843966.1 | MFS transporter | WP_047840993.1 | Aminoglycoside 3-N-acetyltransferase |

| WP_047843373.1 | MFS transporter | KLU58081.1 | Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase |

| WP_047843512.1 | MFS transporter | WP_047841635.1 | Tetracycline resistance protein TetA |

| WP_047844079.1 | Multidrug ABC transporter permease | WP_036614110.1 | d-alanine-d-alanine ligase |

| WP_047844020.1 | Multidrug ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | WP_047843376.1 | Dihydrofolate reductase |

The antibiotic susceptibility of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 was then tested against an array of antimicrobials commonly used to treat nosocomial pneumonia [41]. As can be seen from Table 5, the strain was resistant to macrolides such as erythromycin and azithromycin, as well as to chloramphenicol and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. However, it was sensitive to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, glycopeptides, tetracyclines, lincosamides, and fluoroquinolones.

Table 5.

Antibiotic susceptibility of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400

| Antibiotic | Susceptibility |

|---|---|

| Amoxiclav | S |

| Ampicillin | S |

| Penicillin | S |

| Vancomycin | S |

| Cefotaxime | S |

| Erythromycin | R |

| Chloramphenicol | R |

| Azithromycin | R |

| Gentamicin | S |

| Amikacin | S |

| Kanamycin | S |

| Clindamycin | S |

| Doxycycline | S |

| Ciprofloxacin | S |

| Neomycin | S |

| Tetracycline | S |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | R |

S sensitive, R resistant

Discussion

Bacteria that colonize the oral cavity are important pathogenic agents of pneumonia and other opportunistic infections, especially in immunocompromised hosts. We have now identified one such bacterium, Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400, a novel species that was isolated from children with acute leukemia [28].

Whole-genome analysis indicated that this spore-forming bacterium harbors known virulence factors such as hemolysin, degradative enzymes, adhesins, and flagella. Moreover, CD4+ T-cell-stimulating antigen, a superantigen that causes toxic shock, is also present, along with other virulence determinants such as peptidases, ureases, lipases, and chitinases. Chemotaxis proteins were also found, suggesting that the isolate, which is motile, is capable of chemotaxis [42].

The detection of a strain such as Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 in patients with hematological malignancies is a critical result, especially in light of in vivo studies. In these experiments, mice intranasally challenged with at least 8.5 log10 CFU of the isolate died from pneumonia, and were found to have infected lungs as well as spleen, indicating dissemination of the infection. Taken together, the data suggest that the strain not only presents genetic features of pathogenic bacteria, but may indeed trigger a life-threatening infection.

In addition, the genome of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 features numerous multidrug efflux transporters known to confer intrinsic and acquired resistance to many antibiotics used in clinical practice [43]. These proteins catalyze uptake, efflux, diffusion, solute exchange, and other mechanisms of bacterial defense against xenobiotics [44, 45]. In addition, these transporters are not drug-specific and are associated with multidrug resistance [46].

Moreover, the isolate contains two SMR efflux pumps, which are hallmarks of nosocomial infections and imply that Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 is most likely a circulating hospital strain, or a strain circulating among hematology patients [47]. SMR efflux pumps confer nosocomial antibiotic resistance and poor sensitivity to biocidal quaternary ammonium compounds [48, 49]. Notably, SMR proteins have never been previously found in Paenibacillus.

We detected chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, macrolide ABC transporter, vancomycin resistance protein, and FosB, which confer resistance to chloramphenicol, macrolide, vancomycin, and fosfomycin, respectively [50–52]. A bacteriocin resistance gene was also found, as were tetracycline resistance genes, including TetA [53, 54]. d-ala-d-ala ligase confers cycloserine resistance, while dihydrofolate reductase A is associated with resistance to trimethoprim and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [55, 56]. In addition, the genome contains resistance genes to β-lactams, including metal-dependent hydrolases, as well as resistance genes to chemotherapeutic drugs.

Nevertheless, many resistance genes of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 are not expressed, in accordance with the idea that many mutations do not lead to resistant phenotype [57]. Sporulation, such as in Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400, preserves and disperses genetic material such as antibiotic resistance genes to overcome harsh environmental conditions [58, 59]. These spores may be particularly hazardous to immunocompromised patients.

Conclusions

This study expands the number of poorly characterized Paenibacillus spp. that may cause pulmonary disease in humans [18]. We provide virulence and antibiotic resistance data based on draft genomes and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. We also demonstrate the ability of the strain to trigger pneumonia in vivo, and to invade spleen tissue. Our data may have important implications in the clinic, as the oral microbial flora in patients with hematological malignancies could be a reservoir of pneumonia-causing agents.

Whether Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 is more prevalent in individuals with acute leukemia remains to be established. However, it is clear that the isolate may have direct clinical implications for patients with therapy-induced immunosuppression. We now intend to determine the prevalence of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400 among different groups of patients, as well as among patients beyond hematology and bone marrow transplantation units.

Availability of supporting data

The complete genome has been deposited in GenBank under the Accession No. LELF01000000. The type strain is deposited in the Deutsche Sammlung fur Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen under Accession Number DSM 100755.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed experiments: VT, GT. Performed experiments: VT, GT, MV. Analyzed the data: VT, GT, MV. Contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools: VT, GT. Helped draft the manuscript: GT, MV. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Albert Tai for performing sequencing at the Genomics Core Facility of Tufts University and for his assistance in completing the project.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

George Tetz, Phone: +1-646-617-30-88, Email: georgetets@gmail.com.

Victor Tetz, Phone: +7-921-904-27-11, Email: vtetzv@yahoo.com.

Maria Vecherkovskaya, Phone: +7-921-904-27-11, Email: mashavecher@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Dores GM, Devesa SS, Curtis RE, Linet MS, Morton LM. Acute leukemia incidence and patient survival among children and adults in the United States, 2001–2007. Blood. 2012;119:34–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-347872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faderl S, Kantarjian H. Leukemias: principles and practice of therapy. New York: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rolston KV. Challenges in the treatment of infections caused by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in patients with cancer and neutropenia. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;Supplement 4:S246–S252. doi: 10.1086/427331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frias-Lopez J. Targeting specific bacteria in the oral microbiome. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:527–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labeau SO, Van de Vyver K, Brusselaers N, Vogelaers D, Blot SI. Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia with oral antiseptics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:845–854. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Xue J, Zhou X, You M, Du Q, Yang X, Jingzhi H, Jing Z, Lei C, Mingyun L, et al. Oral microbiota distinguishes acute lymphoblastic leukemia pediatric hosts from healthy populations. PLoS One. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West CE, Renz H, Jenmalm MC, Kozyrskyj AL, Allen KJ, Vuillermin P, Prescott SL. The gut microbiota and inflammatory noncommunicable diseases: associations and potentials for gut microbiota therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li K, Bihan M, Yooseph S, Methe BA. Analyses of the microbial diversity across the human microbiome. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oakley BB, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM, Fredricks DN. Diversity of human vaginal bacterial communities and associations with clinically defined bacterial vaginosis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4898–4909. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02884-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tetz G, Tetz V, Vecherkovskaya M. Complete genome sequence of Paenibacillus sp. strain VT 400, isolated from the saliva of a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genome Announc. 2015 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00894-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoyles L, Honda H, Logan NA, Halket G, La Ragione RM, McCartney AL. Recognition of greater diversity of Bacillus species and related bacteria in human faeces. Res Microbiol. 2012;163:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tetz G, Tetz V. Complete genome sequence of Bacilli bacterium strain VT-13-104 isolated from the intestine of a patient with duodenal cancer. Genome Announc. 2015 doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00705-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setlow P. Mechanisms for the prevention of damage to DNA in spores of Bacillus species. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1985;49:29–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol. 2000;64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barra-Carrasco J, Hernandez-Rocha C, Ibáñez P, Guzman-Duran AM, Álvarez-Lobos M, Paredes-Sabja D. Clostridiumdifficile spores and its relevance in the persistence and transmission of the infection. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2014;31:694–703. doi: 10.4067/S0716-10182014000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell AD. Bacterial spores and chemical sporicidal agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:99–119. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neumann S, Krause SW, Maschmeyer G, Schiel X, von Lilienfeld-Toal M. Primary prophylaxis of bacterial infections and Pneumocystisjirovecii pneumonia in patients with hematological malignancies and solid tumors. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:433–442. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1698-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim K, Lee K, Yu H, Ryoo S, Park Y, Lee J. Paenibacillus sputi sp. nov., isolated from the sputum of a patient with pulmonary disease. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:2371–2376. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.017137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padhi S, Dash M, Sahu R, Panda P. Urinary tract infection due to Paenibacillus alvei in a chronic kidney disease: a rare case report. J Lab Physicians. 2013;5:133. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.119872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouyang J, Pei Z, Lutwick L, Dalal S, Yang L, Cassai N, Sandhu K, Hanna B, Wieczorek R, Bluth M, Pincus MR. Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus: a new cause of human infection, inducing bacteremia in a patient on hemodialysis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008;38:393–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Brown GR, Maglott DR. NCBI Reference Sequences (RefSeq): current status, new features and genome annotation policy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D130–D135. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests: approved standard. M2-A11. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (US). Committee on Care, Use of Laboratory Animals, & National Institutes of Health (US). Division of Research Resources 1985. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academies.

- 28.Crandon JL, Kuti JL, Nicolau DP. Comparative efficacies of human simulated exposures of telavancin and vancomycin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a range of vancomycin MICs in a murine pneumonia model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:5115–5119. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00062-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clair G, Roussi S, Armengaud J, Duport C. Expanding the known repertoire of virulence factors produced by Bacillus cereus through early secretome profiling in three redox conditions. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1486–1498. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000027-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen LM, Tisa LS. Influence of temperature on the physiology and virulence of the insect pathogen Serratia sp. strain SCBI. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:8840–8844. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02580-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.LaGier MJ, Bilokopytov I, Cockerill B, Threadgill DS. Identification and characterization of a putative chemotaxis protein, CheY, from the oral pathogen Campylobacter rectus. Internet J Microbiol. 2014 doi: 10.5580/IJMB.21300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferry T, Thomas D, Genestier AL, Bes M, Lina G, Vandenesch F, Etienne J. Comparative prevalence of superantigen genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing sepsis with and without septic shock. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:771–777. doi: 10.1086/432798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galperin MY, Mekhedov SL, Puigbo P, Smirnov S, Wolf YI, Rigden DJ. Genomic determinants of sporulation in Bacilli and Clostridia: towards the minimal set of sporulation-specific genes. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14:2870–2890. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Saier MH. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dean M, Hamon Y, Chimini G. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1007–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horn C, Bremer E, Schmitt L. Functional overexpression and in vitro re-association of OpuA, an osmotically regulated ABC-transport complex from Bacillus subtilis. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5765–5768. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He X, Szewczyk P, Karyakin A, Evin M, Hong WX, Zhang Q, Chang G. Structure of a cation-bound multidrug and toxic compound extrusion transporter. Nature. 2010;467:991–994. doi: 10.1038/nature09408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jack DL, Yang NM, Saier H. The drug/metabolite transporter superfamily. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:3620–3639. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calle Y, Palomares T, Castro B, del Olmo M, Bilbao P, Alonso-Varona A. Tunicamycin treatment reduces intracellular glutathione levels: effect on the metastatic potential of the rhabdomyosarcoma cell line S4MH. Chemotherapy. 2000;46:408–428. doi: 10.1159/000007322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang H, Kim T, Kim W, Choi C, Lee J, Kim G, Bae D. Outcome and reproductive function after cumulative high-dose combination chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) for patients with ovarian endodermal sinus tumor. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.American Thoracic Society Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harshey RM. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:249–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salavert M, Calabuig E. Role of daptomycin in the treatment of infections in patients with hematological malignancies. Med Clin. 2010;135:36–47. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7753(10)70039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jack DL, Storms ML, Tchieu JH, Paulsen IT, Saier MH. A broad-specificity multidrug efflux pump requiring a pair of homologous SMR-type proteins. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2311–2313. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.8.2311-2313.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saier MH, Jr, Paulsen IT., Jr Phylogeny of multidrug transporters. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12:2015–2213. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piddock LJ. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps? Not just for resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:629–636. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fraimow HS, Tsigrelis C. Antimicrobial resistance in the intensive care unit: mechanisms, epidemiology, and management of specific resistant pathogens. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27:163–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Costa SS, Mourato C, Viveiros M, Melo-Cristino J, Amaral L, Couto I. Description of plasmid pSM52, harbouring the gene for the Smr efflux pump, and its involvement in resistance to biocides in a meticillin-resistant Staphylococcusaureus strain. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;5:490–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinstein RA, Hooper DC. Efflux pumps and nosocomial antibiotic resistance: a primer for hospital epidemiologists. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1811–1817. doi: 10.1086/430381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi N, Nishino K, Yamaguchi A. Novel macrolide-specific ABC-type efflux transporter in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5639–5644. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5639-5644.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galopin S, Cattoir V, Leclercq R. A chromosomal chloramphenicol acetyltransferase determinant from a probiotic strain of Bacillus clausii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;296:185–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson MK, Keithly ME, Harp J, Cook PD, Jagessar KL, Sulikowski GA, Armstrong RN. Structural and chemical aspects of resistance to the antibiotic fosfomycin conferred by FosB from Bacillus cereus. Biochemistry. 2013;52:7350–7362. doi: 10.1021/bi4009648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Butcher BG, Helmann JD. Identification of Bacillus subtilis σW-dependent genes that provide intrinsic resistance to antimicrobial compounds produced by Bacilli. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:765–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levy SB, McMurry LM, Burdett V, Courvalin P, Hillen W, Roberts MC, Taylor DE. Nomenclature for tetracycline resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1373–1374. doi: 10.1128/AAC.33.8.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caceres NE, Harris NB, Wellehan JF, Feng Z, Kapur V, Barletta RG. Overexpression of the d-alanine racemase gene confers resistance to d-cycloserine in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5046–5055. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5046-5055.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eliopoulos GM, Huovinen P. Resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1608–1614. doi: 10.1086/320532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suzuki S, Horinouchi T, Furusawa C. Prediction of antibiotic resistance by gene expression profiles. Nat Commun. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fenselau C, Havey C, Teerakulkittipong N, Swatkoski S, Laine O, Edwards N. Identification of β-lactamase in antibiotic-resistant Bacillus cereus spores. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:904–906. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00788-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laflamme C, Gendron L, Turgeon N, Filion G, Ho J, Duchaine C. In situ detection of antibiotic-resistance elements in single Bacillus cereus spores. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2009;32:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]