Abstract

Background

Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV; Phlebovirus, Bunyaviridae) is a mosquito–borne, zoonotic pathogen. In Senegal, RVFV was first isolated in 1974 from Aedes dalzieli (Theobald) and thereafter from Ae. fowleri (de Charmoy), Ae. ochraceus Theobald, Ae. vexans (Meigen), Culex poicilipes (Theobald), Mansonia africana (Theobald) and Ma. uniformis (Theobald). However, the vector competence of these local species has never been demonstrated making hypothetical the transmission cycle proposed for West Africa based on serological data and mosquito isolates.

Methods

Aedes vexans and Cx. poicilipes, two common mosquito species most frequently associated with RVFV in Senegal, and Cx. quinquefasciatus, the most common domestic species, were assessed after oral feeding with three RVFV strains of the West and East/central African lineages. Fully engorged mosquitoes (420 Ae. vexans, 563 Cx. quinquefasciatus and 380 Cx. poicilipes) were maintained at 27 ± 1 °C and 70–80 % relative humidity. The saliva, legs/wings and bodies were tested individually for the RVFV genome using real-time RT-PCR at 5, 10, 15 and 20 days post exposure (dpe) to estimate the infection, dissemination, and transmission rates. Genotypic characterisation of the 3 strains used were performed to identify factors underlying the different patterns of transmission.

Results

The infection rates varied between 30.0–85.0 % for Ae. vexans, 3.3–27 % for Cx. quinquefasciatus and 8.3–46.7 % for Cx. poicilipes, and the dissemination rates varied between 10.5–37 % for Ae. vexans, 9.5–28.6 % for Cx. quinquefasciatus and 3.0–40.9 % for Cx. poicilipes. However only the East African lineage was transmitted, with transmission rates varying between 13.3–33.3 % in Ae. vexans, 50 % in Cx. quinquefasciatus and 11.1 % in Cx. poicilipes. Culex mosquitoes were less susceptible to infection than Ae. vexans. Compared to other strains, amino acid variation in the NSs M segment proteins of the East African RVFV lineage human-derived strain SH172805, might explain the differences in transmission potential.

Conclusion

Our findings revealed that all the species tested were competent for RVFV with a significant more important role of Ae. vexans compared to Culex species and a highest potential of the East African lineage to be transmitted.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1383-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Mosquito, Oral infection, Vector competence, Viral genetic diversity, Rift Valley fever virus, Senegal

Background

Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) is an emerging mosquito-borne, zoonotic pathogen in the genus Phlebovirus of the family Bunyaviridae. The virus, first isolated in 1930 in Kenya [1], is transmitted primarily through the bites of infected mosquitoes [2–4]. The genome of the virus consists of three negative-stranded RNA segments called large (L), medium (M), and small (S). Other modes of transmission include direct contact with the blood, organs, foetus, tissues or excretions of infected animals through exposure to aerosols. Rift Valley fever (RVF) in animals is characterised by high rates of abortion in pregnant females and deaths of young ruminants. The vast majority of human infections are asymptomatic, but symptomatic infections can lead to severe haemorrhages, meningoencephalitis, retinopathy and in some cases death [5–8]. The disease has cumulatively caused hundreds of thousands of human infections and the deaths of more than 2000 humans and millions of domestic animals in Kenya [9]. To date, no specific treatment against RVF is available. For humans, the available vaccine is restricted to the use for at-risk personnel only, as multiple inoculations are required to achieve protective immunity [10]. Several veterinary vaccine candidates were proposed (MP12, Clone 13, and the Smithburn neurotropic strain), but adverse effects were observed after vaccination [11–13]. Another candidate vaccine (R566) is still currently under investigation [14]. Recently, the MP-12 virus containing a deletion in the NSs gene proved promising as it prevented lethal disease when administered to hamsters [15]. Nonetheless, this new generation of genetically modified vaccines are not yet approved for use in humans or animals.

The recent expansion of RVFV from Africa into Saudi Arabia and Yemen in 2000, and the outbreaks recorded in Africa, particularly those in Mauritania in 2003, 2010 and 2012 [16–19], in Senegal in 2012 and 2013 [20], in Kenya [21, 22], and in Mayotte in 2008 [23], reflect the ongoing emerging potential of the virus. The introduction and spread of the virus into new areas were mainly linked to the migration of infected animals [24], but the dispersal of infected vectors could not be ruled out. As no specific treatment against the RVFV is available, prevention is key, and control of epidemics centred on vector control and the vaccination of cattle and populations at risk (i.e., veterinarians, slaughterhouse staff and medical surveillance personnel, among others).

In Senegal, RVFV was first isolated in 1974 from the mosquito Ae. dalzieli collected in Kedougou during a Yellow Fever (YF) surveillance programme. Following the first extensive RVFV outbreak in Mauritania in 1987, the active surveillance programme implemented resulted in the detection of several animal cases and also the isolation of the virus from several mosquito species, including Ae. fowleri, Ae. ochraceus, Ae. vexans, Cx. poicilipes, Ma.. uniformis and Ma. africana [25–27].

Based on isolates from mosquitoes and the sero-epidemiological data gathered from animals, a transmission cycle similar to that of East Africa was proposed for West Africa. However, this transmission cycle is still hypothetical, because specific entomological parameters such as vector competence of the local species of mosquito for RVFV remain to be determined [28]. Furthermore, although entomological surveillance provided essential information on circulation of the virus and ecology of the vectors, this approach did not determine the effect of RVFV amplification on human populations. Human cases of RVFV are still rare in Senegal [29]. The data generated during a trans-sectional study and following an epizootic event revealed a low seroprevalence of IgG in human populations that ranged from 14.02–22.3 % in 1989 in Yonoféré [30] and 6.12 % in Barkédji in 1993 [29]. The seroprevalence was from 5–26 % amongst children born after the 1987 epidemic, and 25.3 % amongst adults [28, 29]. A low seroprevalence of IgG against RVFV during an investigation of an epidemic was also recorded in Diawara, northern Senegal (5.2 %), and in the south of the country (≤3.1 %) in Kedougou, Tambacounda and Casamance [31–33]. Several factors could explain the difference in infection rates between animals and humans, including the efficiency of transmission by the vector or ecological parameters of the vector.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the vector competence of Ae. vexans and Cx. poicilipes, the two most common mosquito species in the Barkédji area and the species most frequently associated with the RVFV in Senegal, and that of Cx. quinquefasciatus, the most common domestic species, for different strains and lineages of the RVFV.

Methods

Mosquito species

The mosquito species Ae. vexans, Cx. poicilipes and Cx. quinquefasciatus were collected in Barkédji (15°17′N, 14°53′W). Aedes vexans and Cx. quinquefasciatus were chosen as target organisms due to their widespread Afrotropical distribution and potential involvement in the transmission cycle of RVFV in Senegal and neighbouring countries [26, 28]. Aedes vexans is regularly found naturally infected with RVFV in West Africa [25, 27, 34], has a worldwide distribution and is a biting nuisance pest also in Europe and America. The wide distribution of Ae. vexans is a major concern because of the potential for RVFV to invade new geographic areas, as occurred during the epidemic / epizootic in Saudi Arabia [35, 36]. In West Africa, the abundance and the biology of Ae. vexans, including the close interactions with vertebrate hosts, highlight the potentially important role that this species may play in the transmission of RVFV.

Culex quinquefasciatus was selected because this species is the member of the Cx. pipiens complex best adapted to the tropical and sub-tropical regions. Culex pipiens was implicated in the transmission of RVFV during an outbreak in Egypt and on the Arabian Peninsula [36, 37]. In tropical regions, Cx. quinquefasciatus is ubiquitous, colonizing domestic environments year-round because of its association with artificial breeding sites. This species is abundant, anthropophagic and a competent vector for arboviruses in some geographic locations, making it a good candidate for the study of RVFV transmission in urban settings.

Culex poicilipes was targeted in this study as it is considered as one of the main vectors of RVFV in West Africa due to its abundance, bionomics and the number of RVFV strains isolated from this species in Senegal and Mauritania [26, 38]. In our previous studies, the dominance in abundance regularly switched between Cx. poicilipes and Ae. vexans in Barkédji [39, 40]. Feeding preference studies indicated that Cx. poicilipes was mainly attracted to bovines and sheep, adding further indication as to its vectorial potential [41].

Virus strains and preparation of the stocks

The three RVFV strains used in this study were isolated from goats (AnD133719), mosquitoes (ArD141967) (both West African lineages), and humans (SH172805, East/central African lineage) in Mauritania in the years 1998, 2000, and 2003, respectively (Table 1). The viral stock of each strain used to infect mosquitoes was prepared from the brains of suckling mice inoculated intracerebrally with 20 μl of the virus. Brains were triturated in Leibovitz-15 (L-15) medium (GibcoBRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing penicillin and streptomycin (Sigma, GmBh, Germany) and 10 % FBS (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA). After centrifugation, the suspension was aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C.

Table 1.

RVFV strains used in this study, and titre of virus in the infectious blood meal after exposure

| Virus strain | Host Origin | Geographic Origin | Year of isolation | Passage history | Lineage | Virus titer post exposure (PFU/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ae. vexans | Cx. quinquefasciatus | Cx. poicilipes | ||||||

| SHM172805 | Human | Mauritania | 2003 | 3 | East/Central Africa | 4.5 × 106 | 1.5 × 106 | 9.7 × 108 |

| ArD141967 | Cx. poicilipes | Mauritania | 2000 | 4 | West Africa | 5.5 × 106 | 5.5 × 108 | 1.1 × 107 |

| AnD133719 | Goat | Mauritania | 1998 | 7 | West Africa | 9.5 × 106 | 1.7 × 106 | 3 × 106 |

Experimental infection procedure

Three to five day-old F1 generation female mosquitoes were starved for 48 h and then exposed for 1 h to an infectious blood meal, using the previously described artificial feeding method using a mouse skin membrane [42]. The infectious blood meal contained at equal volume, washed rabbit erythrocytes, foetal bovine serum (FBS) and the viral suspension of one of the three natural RVFV strains described above. As a phagostimulant, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was added to a final concentration of 0.005 M. For each infection experiment, a sample of the virus-blood suspension was collected at the end of the mosquito feeding for virus titration. At the end of feeding, the mosquitoes were cold anaesthetised, and fully engorged specimens were selected and subsequently maintained in an incubator at 27 °C, a relative humidity of 70–80 % and 10 % sucrose for food. Between 25 and 40 individuals were randomly selected for each batch at 5 days post exposure (dpe), 25 to 50 at 10 dpe, 36 to 100 at 15 dpe, and 6 to 66 at 20 dpe (Fig. 3). Mosquitoes were again cold anaesthetised, and the legs and wings removed and put together in a tube. Each of these mosquitoes was then forced to salivate individually into a capillary tube containing FBS. After 15–20 min of salivation, the mosquitoes were removed, and the FBS-saliva mix was added into a vial containing 500 μl of L-15 medium.

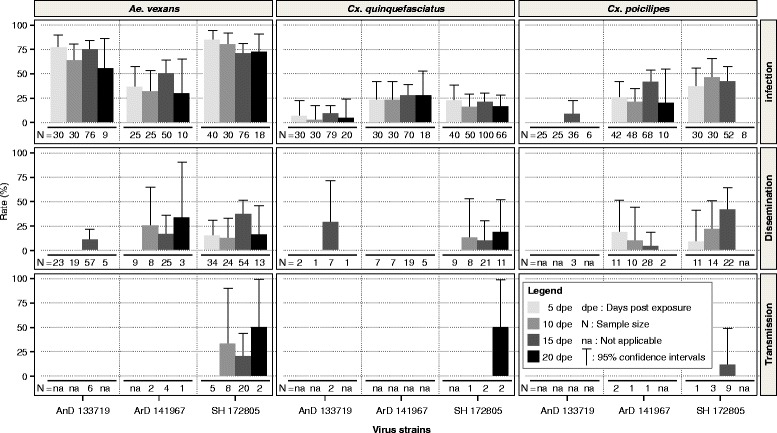

Fig. 3.

RVFV infection, dissemination and transmission rates throughout incubation periods as indicated for Ae. vexans, Cx. quinquefasciatus and Cx. poicilipes that were orally exposed to infectious blood meal containing 106-108 PFU/ml virus suspension with RVFV strains SH72805, ArD14196 or AnD133719. N: number of specimens tested. dpe: day post exposure

Virus detection in mosquitoes

The mosquito bodies, legs/wings and collected saliva were stored separately at −80 °C until virus detection was attempted by real-time RT-PCR. All mosquito bodies as well as the legs/wings of infected bodies and saliva of infected legs/wings were tested for presence of virus. The samples were homogenised in 500 μl of L-15 cell culture medium containing 20 % FBS and were then centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C. For real-time PCR, 100 μl of supernatant was used for RNA extraction using the QIAamp Viral RNA Extraction Kit (QIAgen, Heiden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA was amplified using ABI Prism 7000 SDS Real-Time apparatus (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the QuantiTect kit (QIAgen).

The RT-PCR was performed in a 25 μl reaction volume containing 5 μl of extracted RNA (Triplicate), 2x QuantiTect Probe, RT-Master Mix, 10 μM of each primer and 200 nM of the probe. The specific primers and probe sequences for RVFV used were first described in Weidman et al. [43]. The thermal profile was as follows: a single cycle of reverse transcription for 10 min at 50 °C, 15 min at 95 °C for reverse transcriptase inactivation and DNA polymerase activation, and then 40 amplification cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and of 1 min at 60 °C (annealing-extension step). Fluorescence was analysed at the end of the amplifications.

Viral RNA extraction, RT-PCR and sequencing

The RNA were extracted from the three viral stocks (AnD133719, SHM172805 and ArD141967) and were used as templates for RT-PCR. Specific primers (Table 2), the M-MLV system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the Go-Taq PCR Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) were used for cDNA synthesis and amplification, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All primers used to amplify the S and M segments were designed according to RVFV sequences available in GenBank. Accession numbers of all RVFV sequences used to design the primers are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1. The PCR products of the expected sizes were purified directly from the agarose gel using a QIAgen Gel extraction kit and sequenced by Cogenics (Beckman Coulter Genomics, Essex, United Kingdom). Sequencing was performed in both directions, using the original reverse and forward primers as for the amplification.

Table 2.

List of primers used

| Nom | Segment | Position | Sequence | Tm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSng | S | 31–48 | TATCATGGATTACTTTCC | 48 |

| NSca | S | 841–824 | CCTTAACCTCTAATCAAC | 50 |

| M1F | M | 3–22 | ACAAAGACCGGTGCAACTTC | 53.9 |

| M1R | M | 1120–1140 | CCAYGCAAAGGGTATGCAAT | 53.2 |

| M2F | M | 1035–1054 | TGAGGACTCTGAATTRCACCT | 48.7 |

| M2R | M | 2395–2415 | TCCAGAGAGTTGAGCCTTGC | 53.3 |

| MRV1a | M | 3050–3068 | CAAATGACTACCAGTCAGC | 44.6 |

| MRV2g | M | 2262–2292 | GGTGGAAGGACTCTGCGA | 52.5 |

| M3F | M | 2979–2998 | CAGTCCTCAGTGAGCYCATA | 46.1 |

| M3R | M | 3763–3782 | TCTCGGTTCTGGRGTGTGAA | 52.5 |

Data analysis

Detection of RVFV in the mosquito bodies without the subsequent detection of the infection in the legs/wings was considered a non- disseminated infection, which was limited to the midgut. Conversely, detection of the virus in both the mosquito legs/wings and saliva indicated a disseminated infection from the midgut into the mosquito haemocoel and the potential for transmission, respectively. The infection rate (number of infected mosquito bodies per 100 mosquitoes tested), the dissemination rate (number of mosquitoes with infected legs/wing per 100 mosquitoes infected) and the transmission potential (number of mosquitoes with infected saliva per 100 mosquitoes with infected legs/wings) were calculated and compared for each mosquito species, according to dpe and the viral strains. Fisher’s exact tests were performed to compare the rates of infection, dissemination and transmission using the R statistical software package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Nucleotides sequences from Beckman Coulters were analysed and assembled with GeneStudio, version 2.2.0.0 (http://genestudio.com/). The amino acid sequences were then aligned using MEGA 5.05 software [44] to identify variable motifs between the human (SHM172805) and other strains that could explain the different patterns in the mosquito species tested.

Results

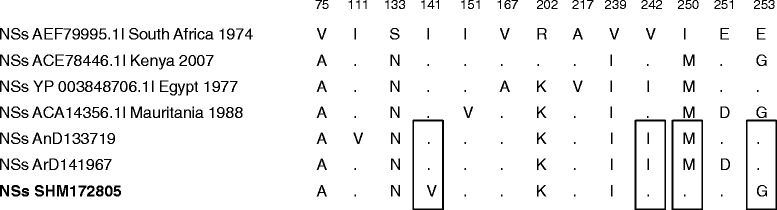

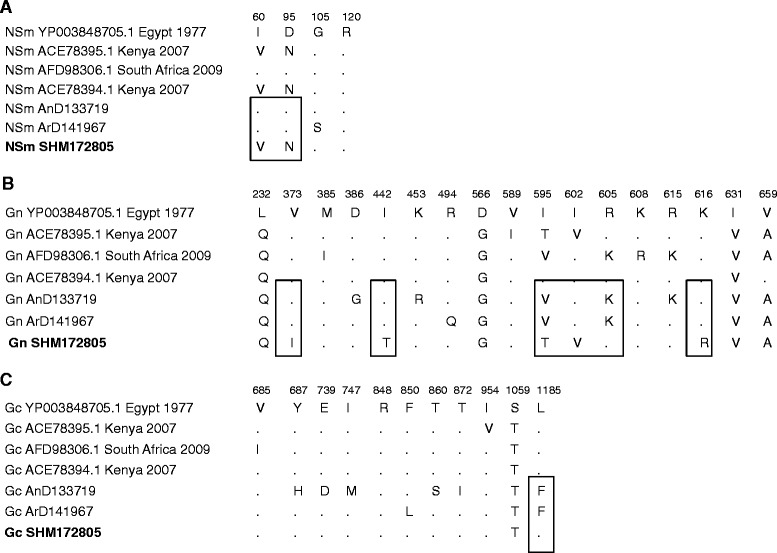

The sequences of the S and M segments of the coding region obtained for the three strains of virus were aligned using MEGA. Based on these alignments, variation in amino acids were observed in the NSs, NSm, Gc and Gn proteins of the human strain (SHM172805) compared to the two other strains (Figs. 1 and 2). This variability occurred primarily among amino acids of the same type (I/V/M and R/K) but also between amino acids of different types, acid/polar, polar/apolar, and aliphatic/aromatic (D/N, V/T, L/F respectively). The N-linked glycosylation sites of the envelope proteins were all conserved.

Fig. 1.

Alignment of S segment. NSs proteins were aligned and variable amino acids were shown with their positions refer to the genome sequence of South Africa 1974 (Accession number: AEF79995.1). Human strain SHM172805 (East/Central African lineage) is in bold. Dots: conserved amino acids. Rectangles: variables amino acids in the human strain sequence compared to ArD141967 and AnD133719 (West African lineage)

Fig. 2.

Alignment of M segment. M proteins were aligned and variable amino acids in NSm, Gn and Gc proteins were shown with their positions refer to the genome sequence of Egypt 1977 (Accession number: YP003848705.1). Human strain SHM172805 is in bold. Dots: conserved amino acids. Rectangles: variables amino acids in the human strain sequence compared to ArD141967 and AnD133719

A total of 420 Ae. vexans, 563 Cx. quinquefasciatus and 380 Cx. poicilipes were tested for RVFV competence. All three virus strains (with virus titers ranging from 1.5× 106 pfu/ml to 9.7 × 108 pfu/ml) infected the three species of mosquito and were disseminated, but only the East African lineage RVFV was capable of being transmitted by all three species. Infection rates varied between 30 and 85 % for Ae. vexans, 3.3–27 % for Cx. quinquefasciatus and 8.3–46.7 % for Cx. poicilipes. For each mosquito-virus combination, the infection rates were comparable at each dpe, as well between the different dpe. However, significant variation was detected when comparing the infection rates by the different virus strains at different dpe (Fig. 3 and Additional file 2: Table S2).

The infection rates of Ae. vexans with the ArD141967 strain were significantly lower than those with the SH172805 strain (P ≤ 0.04). The same trend was observed between the ArD141967 and the AnD133719 strains (P ≤ 0.03), except at 20 dpe (P = 0.3). However, no significant difference was recorded between the infection rates of AnD133719 and SH172805 (P ≥ 0.25). With Cx. quinquefasciatus, the infection rates were similar between SH172805 and ArD141967 strains. AnD133719 was the only strain that exhibited infection rates significantly lower than those of the SH172805 strain (P = 0.03) and the ArD141967 strain (P = 0.004).

For Cx. poicilipes, no significant differences were observed irrespective of dpe (P > 0.05), except at 10 and 15 dpe with the ArD141967 strain (P = 0.021). Comparison among the viral strains revealed that at 10 dpe, the SH172805 strain was more infectious than the ArD141967 strain (P = 0.016), and at 15 dpe, the infection rate of the AnD133719 strain was significantly lower than both the ArD141967 (P = 0.00049) and SH172805 strain (P = 0.0002).

Based on a pairwise analysis of infection rates between the species, Ae. vexans was generally more susceptible to infection than Cx. quinquefasciatus. The unique exception was the infection obtained with the ArD141967 strain at 15 dpe, when the infection rate of Ae. vexans was significantly higher than that of Cx. quinquefasciatus (P = 0.001). Indeed using the same strain of virus, a comparable rate of infection was found for Ae. vexans and Cx. quinquefasciatus at 5, 10, and 20 dpe (P ≥ 0.3).

Independent of the virus strain used, dissemination rates were relatively low for the three species of mosquitoes ranging from 10.5–37 % in Ae. vexans, from 9.5–28.6 % in Cx. quinquefasciatus and from 3–40.9 % in Cx. poicilipes. Dissemination was recorded relatively quickly in Ae. vexans at 5 dpe for the SH172805 strain but was delayed to 10, and 15 dpe, for the ArD141967 and AnD133719 strains, respectively. With the exception of the significant difference observed at 15 dpe between the AnD133719 and SH172805 strains (P = 0.001), the dissemination rates were comparable for all virus strains and incubation periods (P ≥ 0.07). In Cx. quinquefasciatus, the dissemination rates remain similar irrespective of the dpe (P ≥ 0.1). This species did not disseminate the ArD141967 strain, despite the high viral titres of 5.5108 PFU/ml detected in the blood meal post-feeding. The observation was similar for Cx. poicilipes, which did not disseminate the animal strain (AnD133719).

For all mosquito species tested, only the SH172805 strain was transmitted (i.e. present in saliva) from 10 dpe and thereafter for Ae. vexans, 15 dpe for Cx. poicilipes and only after 20 dpe for Cx. quinquefasciatus. The transmission rates ranged from 13.–33.3 % for Ae. vexans and was 11.1 % for Cx. poicilipes and 50 % for Cx. quinquefasciatus, but the differences between the three species and the dpe were not significant (P ≥ 0.05).

Discussion

Our study showed that the three mosquito species were susceptible to infection by the different RVFV strains with Ae. vexans mosquitoes being more susceptible than Cx. poicilipes or Cx. quinquefasciatus. The highest infection rates were obtained with Ae. vexans, which was also the only species that disseminated all the virus strains and transmitted the SH172805 strains at different dpe. Despite a lower viral titre (≈ 106 PFU/ml) in the blood meal post-feeding, the rates of infection, dissemination and transmission rates obtained were as high as those obtained in US populations of Ae. vexans that were exposed to a viraemic animal that exceeded or was equal to 108.5 PFU/ml [45]. The rates of infection, dissemination and transmission were 47.9–95.4 %, 10.3–60.8 % and 25–100 %, respectively. However, our results differed from those of other studies [46] that reported absence of competence after exposure to viral titres that ranged from 107.9–109 PFU/ml and led to an infection rate of only 15 % without dissemination or transmission. Geographical diversity in the competence of Ae. vexans has already been observed in populations from different localities in the USA. Populations from Louisiana and Florida exhibited 27 % transmission rates, whereas the rate of transmission in colonies from Colorado and California was only 1 % [47]. Indeed, the Ae. vexans complex includes three subspecies: Ae. vexans vexans (Meigen, 1830) found in Europe, Ae. vexans nipponii (Theobald, 1907) from eastern Asia, and Ae. vexans arabiensis (Patton, 1905) is the only representative in Africa. Because this study focused on only one strain of each mosquito species and vector competence of mosquito populations can vary spatially, our results may not apply to population from other regions of West Africa. Further studies are needed to evaluate the vector competence of other populations of these species for RVFV.

The low infection rates among the two Culex species observed in our study are consistent with previous results of Cx. quinquefasciatus from South Africa, Australia and the south-eastern United States [45, 47–50], with a maximum infection rate of 26 %, without dissemination and transmission. The low transmission rate (11.1 %) found here for Cx. poicilipes is similar to the results of a previous South African study at 15 dpe [51]. This transmission rate could become higher with longer incubation periods, as it was suggested that the South African population of Cx. poicilipes reached 80 % transmission after 30 days of extrinsic incubation.

Only the RVFV strain belonging to the East African lineage (SH172805) was transmitted. These observed variations were not caused by differences in viral titres because no significant correlation was observed between viral titres and infection rates. Contrary to our findings, Turell et al. [47] found that mosquito infection and dissemination rates were higher when mosquitoes were exposed to higher viral doses. This discordance could be explained by differences in mosquito strains and the experimental protocol.

The genetic variability of the virus strains used in our experiment could explain the differences in patterns of infection and transmission. The results of the sequence analysis of a portion of the genome at the L, M and S segments provided some support for this hypothesis. Indeed, in addition to classification into the East African lineage, the alignment of partial segments showed a number of differences between the M and S segments of the SH172805 strain to those of the other West African strains. Amino acid changes were detected in the NSs, NSm, Gc and Gn proteins of the human East African strain compared with those of the West African strains. Notably, the M segment proteins are essential and necessary for virus spread. Indeed the Gn and Gc proteins are implicated in the RVFV entry during infection, although the cell receptor remains unknown [52, 53]. The M segment proteins also play important roles in the assembly of the Golgi and the budding of viral particles [54]. It has been shown that the NSm protein has an anti-apoptotic function and a negative effect on virus development in the cell [55–57]. Additionally, NSm has been described to play a functional role in influencing vector competence for RVFV at the level of the midgut barrier [58]. The NSs protein acts on the antiviral response of mammalian cells by direct or indirect inhibition of transcription factor [59, 60]. Alone or combined, these two proteins (NSs and NSm) affect vector competence of some species by reducing the rate of infection or the potential to transmit the virus [61]. Therefore, the single amino acid mutations observed in all these proteins could influence the viral replication and lead to different patterns of transmission. A single amino acid mutation can indeed enhance transmission in a mosquito vector. In chikungunya virus, a single mutation (A226V) in the E1 glycoprotein enhanced viral transmission by Ae. albopictus [62, 63]. Further studies are required to assess the effects of these amino acid differences between RVFV strains. Studies with reassortant viruses from these strains or genetically engineered viruses could pinpoint what segment exactly carries determinants for the competence phenotype to further inform risk analysis. The lower susceptibility of Cx. quinquefasciatus, which is the most abundant domestic vector and a highly anthropophilic species may explain why human cases of RVFV are still rare in Senegal. Only the strain belonging to the East African lineage (SH172805) was transmitted, suggesting that this lineage is more infectious for mosquito vectors than the West African lineage in agreement with the fact than more RVFV outbreaks were observed in East Africa compared to West Africa.

Considering that Ae. vexans, Cx. poicilipes and Cx. quinquefasciatus exhibited a minimum EIP of 10, 15 and 20 days, respectively and given their estimated survival rates obtained from previous studies [64, 65], the infective life expectancy was estimated at between (0.91)10 to (0.96)10 for Ae. vexans, between (0.70)15 to (0.79)15 for Cx. poicilipes, and between (0.871)20 and (0.883)20 for Cx. quinquefasciatus. This means that 38.9–66.4 % of Ae. vexans, but only 0.5–2.9 % of Cx. poicilipes and 6.31–8.3 % of Cx. quinquefasciatus populations would be expected to survive long enough for transmission to occur.ConclusionOur findings revealed that all the species tested were competent for RVFV with a significant more important role of Ae. vexans compared to Cx. poicilipes or Cx. quinquefasciatus and a highest potential of the East African lineage to be transmitted.

Acknowledgements

This study was part of a project supported by the EMIDA ERA Net (contract N° 219235). AK, the project coordinator is funded by the UK MRC (grant number MC_UU_12014/8). The authors would like to thank Anna Bella Failloux Institut Pasteur, Department of Virology, Arboviruses and Insect Vectors for comments suggestions and critical review of the manuscript, Amadou Thiaw and Abdou Karim Bodian for their technical assistance in the insectary and all the population of Barkédji for their collaboration.

Additional files

GenBank accession numbers of Rift Valley Fever Virus sequences used to design the primers used in this study. (DOC 19 kb)

Mosquito tested, number infected, that disseminated and transmitted by species and Rift valley fever strains. (XLS 25 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MD, AAS, AK conceived and designed the study. EN’D CTD, AG, DD, ID and YB carried out the fieldwork and the vector competence studies. GF, NDSB, AAS performed molecular and phylogenetic studies. CT carried the statistical analysis. EN’D, DD, GF and MD analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors read, critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

El Hadji Ndiaye, Email: elndiaye@pasteur.sn.

Gamou Fall, Email: gamou.fall@pasteur.sn.

Alioune Gaye, Email: agaye@pasteur.sn.

Ndeye Sakha Bob, Email: nsbob@pasteur.sn.

Cheikh Talla, Email: ctalla@pasteur.sn.

Cheikh Tidiane Diagne, Email: ctdiagne@pasteur.sn.

Diawo Diallo, Email: ddiallo@pasteur.sn.

Yamar BA, Email: ba@pasteur.sn.

Ibrahima Dia, Email: dia@pasteur.sn.

Alain Kohl, Email: alain.kohl@glasgow.ac.uk.

Amadou Alpha Sall, Email: asall@pasteur.sn.

Mawlouth Diallo, Phone: +221 33 839 92 28, Email: diallo@pasteur.sn.

References

- 1.Daubney R, Hudson JR, Garnham PC. Enzootic hepatitis or Rift Valley fever. An undescribed virus disease of sheep cattle and man from East Africa. J Path Bact. 1931;34(4):545–79. doi: 10.1002/path.1700340418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lutomiah J, Omondi D, Masiga D, Mutai C, Mireji PO, Ongus J, et al. Blood meal analysis and virus detection in blood-fed mosquitoes collected during the 2006–2007 Rift Valley fever outbreak in Kenya. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14(9):656–64. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arum SO, Weldon CW, Orindi B, Landmann T, Tchouassi DP, Affognon HD, et al. Distribution and diversity of the vectors of Rift Valley fever along the livestock movement routes in the northeastern and coastal regions of Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:294. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0907-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nepomichene TN, Elissa N, Cardinale E, Boyer S. Species diversity, abundance, and host preferences of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in two different ecotypes of Madagascar with recent RVFV transmission. J Med Entomol. 2015;52(5):962–9. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjv120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Easterday BC, McGavran H, Roonry JR, Murphy LC. The pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever in lambs. Am J Vet Res. 1962;23:470–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meegan JM, Bailey CL: Rift Valley fever in « Arboviruses Epidemiology and ecology » Edited by TP Monath CRC, Boca Raton, FL 1988;IV:51–76.

- 7.Madani TA, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Jeffri MH, Mishkhas AA, Al-Rabeah AM, Turkistani AM, et al. Rift Valley fever epidemic in Saudi Arabia: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(8):1084–92. doi: 10.1086/378747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Hazmi A, Al-Rajhi AA, Abboud EB, Ayoola EA, Al-Hazmi M, Saadi R, et al. Ocular complications of Rift Valley fever outbreak in Saudi Arabia. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(2):313–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murithi RM, Munyua P, Ithondeka PM, Macharia JM, Hightower A, Luman ET, et al. Rift Valley fever in Kenya: history of epizootics and identification of vulnerable districts. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139(3):372–80. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810001020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittman PR, Liu C, Cannon TL, Makuch RS, Mangiafico JA, et al. Immunogenicity of an inactivated Rift Valley fever vaccine in humans: a 12-year experience. Vaccine. 1999;18:181–9. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muller R, Saluzzo J-F, Lopez N, Dreier T, Turell M, Smith J, et al. Characterization of clone 13, a naturally attenuated avirulent isolate of Rift Valley fever virus, which is altered in the small segment. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:405–11. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saluzzo J, Smith J. Use of reassortant viruses to map attenuating and temperature-sensitive mutations of the Rift Valley fever virus MP-12 vaccine. Vaccine. 1990;8:369–75. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(90)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smithburn KC. Rift Valley fever; the neurotropic adaptation of the virus and the experimental use of this modified virus as a vaccine. British J Exp Pathol. 1949;30:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouloy M, Flick R. Reverse genetics technology for Rift Valley fever virus: current and future applications for the development of therapeutics and vaccines. Antiviral Res. 2009;84:101–18. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gowen BB, Westover JB, Sefing EJ, Bailey KW, Nishiyama S, Wandersee L, et al. MP-12 virus containing the clone 13 deletion in the NSs gene prevents lethal disease when administered after Rift Valley fever virus infection in hamsters. Front Microbiol. 2015;6(651):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faye O, Diallo M, Diop D, Bezeid OE, Bâ H, Niang M, et al. Rift Valley fever outbreak with East-Central African virus lineage in Mauritania, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(7):1016–23. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.061487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ould El Mamy AB. Ould Baba M, Barry Y, Isselmou K, Dia ML, Ba H, Diallo MY, Ould Brahim El Kory M, Diop M, Lo MM, Thiongane Y, Bengoumi M, Puech L, Plee L, Claes F, De La Rocque S, Doumbia B: Unexpected Rift Valley Fever Outbreak Northern Mauritania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1894–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faye O, Ba H, Ba Y, Freire CC, Faye O, Ndiaye O, et al. Reemergence of Rift Valley fever, Mauritania, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:300–3. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.130996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sow A, Faye O, Ba Y, Ba H, Diallo D, Faye O, et al. Rift Valley Fever Outbreak, Southern Mauritania, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:296–9. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.131000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sow A, Faye O, Faye O, Diallo D, Sadio BD, Weaver SC, et al. Rift Valley Fever in Kedougou, Southeastern Senegal, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(3):504–5. doi: 10.3201/eid2003.131174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sang R, Kioko E, Lutomiah J, Warigia M, Ochieng C, O’Guinn M, et al. Rift Valley fever virus epidemic in Kenya, 2006/2007: The entomologic investigations. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(2 Suppl):28–37. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tchouassi DP, Bastos AD, Sole CL, Diallo M, Lutomiah J, Mutisya J, et al. Population genetics of two key mosquito vectors of Rift Valley fever virus reveals new insights into the changing disease outbreak patterns in Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sissoko D, Giry C, Gabrie P, Tarantola A, Pettinelli F, Collet L, et al. Rift Valley Fever, Mayotte, 2007–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(4):568–70. doi: 10.3201/eid1504.081045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munyua P, Murithi RM, Wainwright S, Githinji J, Hightower A, Mutonga D, et al. Rift Valley fever outbreak in livestock in Kenya, 2006–2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(2 Suppl):58–64. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontenille D, Traore-Lamizana M, Zeller H, Mondo M, Diallo M, Digoutte JP. Rift Valley fever in Western Africa: isolations from Aedes mosquitoes during an interepizootic period. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:403–4. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diallo M, Lochouarn L, Ba K, Sall AA, Mondo M, Girault L, et al. First isolation of the Rift Valley fever virus from Culex poicilipes (Diptera: Culicidae) in nature. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:702–4. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ba Y, Sall AA, Diallo D, Mondo M, Girault L, Dia I, et al. Re-emergence of Rift Valley fever virus in Barkédji (Senegal, West Africa) in 2002–2003: identification of new vectors and epidemiological implications. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2012;28:170–8. doi: 10.2987/12-5725.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeller HG, Fontenille D, Traore-Lamizana M, Thiongane Y, Digoutte JP. Enzootic activity of Rift Valley fever virus in Senegal. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:265–72. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thonnon J, Picquet M, Thiongane Y, Lo M, Sylla R, Vercruysse J. Rift Valley fever surveillance in the lower Senegal river basin: update 10 years after the epidemic. Trop Med Int Health. 1999;4:580–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson ML, Chapman LE, Hall DB, Dykstra EA, Ba K, Zeller HG, et al. Rift Valley fever in rural northern Senegal: human risk factors and potential vectors. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:663–75. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saluzzo JF, Chartier C, Bada R, Martinez D, Digoutte JP. La fièvre de la vallée du Rift en Afrique de l’Ouest. Rev Elev Med Vet Pays Trop. 1987;40(3):215–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeller HG, Bessin R, Thiongane Y, Bapetel I, Teou K, Gbaguidi Ala M, et al. Rift Valley fever antibody prevalence in domestic ungulates in several West-African countries (1989–1992) following the 1987,Mauritanian outbreak. Res Virol. 1987;1995(146):14681–5. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(96)80593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monlun E, Zeller H, Le Guenno B, Traoré-Lamizana M, Hervy JP, Adam F, et al. Digoutte JP: [Surveillance of the circulation of arbovirus of medical interest in the region of eastern Senegal] Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1993;86(1):21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fontenille D, Traore-Lamizana M, Diallo M, Thonnon J, Digoutte JP, Zeller HG. New vectors of Rift Valley fever in West Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4(2):289–93. doi: 10.3201/eid0402.980218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jupp PG, Kemp A, Grobbelaar AA, Leman PA, Burt FJ, Alahmed AM, et al. The 2000 epidemic of Rift Valley fever in Saudi Arabia: mosquito vector studies. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16(3):245–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2002.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller BR, Godsey MS, Crabtree MB, Savage HM, Al-Mazrao Y, Al-Jeffri MH, et al. Isolation and genetic characterization of Rift Valley fever from Aedes vexans arabiensis, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(12):1492–4. doi: 10.3201/eid0812.020194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meegan JM, Khalil GM, Hoogstraal H, Adham FK. Experimental transmission and field isolation studies implicating Culex pipiens as a vector of Rift Valley fever virus in Egypt. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:1405–10. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diallo M, Nabeth P, Ba K, Sall AA, Ba Y, Mondo M, et al. Mosquito vectors of the 1998-19999 Rift Valley Fever (RVF) outbreak, and other arboviruses (Bagaza, Sanar, West Nile & Wesselsbron), in Mauritania & Senegal. Med Vet Entomol. 2005;2005(19):119–26. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2005.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diallo D, Talla C, Ba Y, Dia I, Sall AA, Diallo M. Temporal distribution and spatial pattern of abundance of Rift valley fever and West Nile fever vectors in Barkédji, Senegal. J Vector Ecol. 2011;36:426–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2011.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Traore-Lamizana M, Fontenille D, Diallo M, Ba Y, Zeller HG, Mondo M, et al. Arbovirus surveillance from 1990 to 1995 in the Barkédji area (Ferlo) of Senegal, a possible natural focus of Rift Valley fever virus. J Med Entomol. 2001;38:480–92. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ba Y, Diallo D, Dia I, Diallo M. Feeding pattern of Rift Valley Fever virus vectors in Senegal. Implications in the disease epidemiology. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2006;99:283–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diallo M, Ba Y, Faye O, Soumare ML, Dia I, Sall AA. Vector competence of Aedes aegypti populations from Senegal for sylvatic and epidemic dengue 2 virus isolated in West Africa. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:493–8. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weidmann M, Sanchez-Seco MP, Sall AA, Ly PO, Thiongane Y, Lo MM, et al. Rapid detection of important human pathogenic Phleboviruses. J Clin Virol. 2008;41(2):138–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M. Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA version 5. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turell MJ, Dohm DJ, Mores CN, Terracina L, Wallette DL, Hribar LJ, et al. Potential for North American mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit Rift Valley fever virus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2008;24:502–7. doi: 10.2987/08-5791.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iranpour M, Turell MJ, Lindsay LR. Potential for Canadian mosquitoes to transmit Rift Valley fever virus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2011;27:363–9. doi: 10.2987/11-6169.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turell MJ, Wilson WC, Bennett KE. Potential for North American mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit Rift Valley fever virus. J Med Entomol. 2010;47:884–9. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/47.5.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McIntosh BM, Jupp PG, Dos Santos I, Barnard JH. Vector studies on Rift Valley fever virus in South Africa. South Afr Med J. 1980;58:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turell MJ, Kay B. Susceptibility of selected strains of Australian mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to Rift Valley fever virus. J Med Entomol. 1998;35:132–5. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/35.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turell MJ, Lee JS, Richardson JH, Sang RC, Kioko EN, Agawo MO, et al. Vector competence of Kenyan Culex zombaensis and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes for Rift Valley fever virus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2007;23:378–82. doi: 10.2987/5645.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jupp PG, Cornel AJ. Vector competence tests with Rift Valley fever virus land five South African species of mosquito. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1988;4(1):4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Filone CM, Heise M, Doms RW, Bertolotti-Ciarlet A. Development and characterization of a Rift Valley fever virus cell-cell fusion assay using alphavirus replicon vectors. Virology. 2006;356:155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garry CE, Garry RF. Proteomics computational analyses suggest that the carboxyl terminal glycoproteins of Bunyaviruses are class II viral fusion protein (beta-penetrenes) Theor Biol Med Model. 2004;1:10–26. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carnec X, Ermonval M, Kreher F, Flamand M, Bouloy M. Role of the cytosolic tails of Rift Valley fever virus envelope glycoproteins in viral morphogenesis. Virology. 2014;448(5):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Won S, Ikegami T, Peters CJ, Makino S. NSm protein of Rift Valley fever virus suppresses virus induced apoptosis. J Virol. 2007;81:13335–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01238-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerrard SR, Bird BH, Albarino CG, Nichol ST. The NSm proteins of Rift Valley fever virus are dispensable for maturation, replication and infection. Virology. 2007;359(2):459–65. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ikegami T. Molecular biology and genetic diversity of Rift Valley fever virus. Antiviral Res. 2012;95:293–310. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kading RC, Crabtree MB, Bird BH, Nichol ST, Erickson BR, Horiuchi K, et al. Deletion of the NSm virulence gene of Rift Valley fever virus inhibits virus replication in and dissemination from the midgut of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(2):2670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kalveram B, Lihoradova O, Ikegami T. NSs Protein of Rift Valley Fever virus promotes posttranslational downregulation of the TFIIH. J Virol. 2011;85:6234–43. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02255-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Billecocq A, Spiegel M, Vialat P, Kohl A, Weber F, Bouloy M, et al. NSs protein of Rift Valley fever virus blocks interferon production by inhibiting host gene transcription. J Virol. 2004;78:9798–806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9798-9806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crabtree MB, Kent Crockett RJ, Bird BH, Nichol ST, Erickson BR, Erickson BR, et al. Infection and transmission of Rift Valley Fever viruses lacking the NSs and/or NSm Genes in mosquitoes: Potential role for NSm in mosquito infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(5):1639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vazeille M, Moutailler S, Coudrier D, Rousseaux C, Khun H, Huerre M, et al. Two chikungunya isolates from the outbreak of La Reunion (Indian Ocean) exhibit different patterns of infection in the mosquito, Aedes albopictus. PLoS One. 2007;2:1168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arias-Goeta C, Mousson L, Rougeon F, Failloux AB. Dissemination and transmission of the E1-226 V variant of chikungunya virus in Aedes albopictus are controlled at the midgut barrier level. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):57548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ba Y, Diallo D, Kebe CM, Dia I, Diallo M. Aspects of bioecology of two Rift Valley fever virus vectors in Senegal (West Africa): Aedes vexans and Culex poicilipes (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 2005;42:739–50. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2005)042[0739:AOBOTR]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elizondo-Quiroga A, Flores-Suarez A, Elizondo-Quiroga D, Ponce-Garcia G, Blitvich BJ, Contreras-Cordero JF, et al. Gonotrophic cycle and survivorship of Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) using sticky ovitraps in Monterrey, northeastern Mexico. Am J Mosq Control Assoc. 2006;22:10–4. doi: 10.2987/8756-971X(2006)22[10:GCASOC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]