Abstract

Although much had still to be learned, evidence indicating that B-1a lymphocytes very likely belonged to a distinct lineage was largely in place by the time of the first large B-1a conference in 1991. The widely respected group of immunologists attending that meeting (including Tasuko Honjo and Klaus Rajewsky) developed and ultimately published the B-1a notation still in use today. Here, I briefly review some of the early B-1a findings that underlie current studies. I close with a brief summary of recent studies, mainly from my laboratory, showing that the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) we all know and love as the origin of the cells that populate the adult lymphoid and myeloid system today is nonetheless not the origin of the B-1a lymphocytes with which most of us work today.

Keywords: HSC, B lineages, B-1a antibody responses, vaccine development

Introduction

Kyoko Hayakawa discovered CD5+ B cells shortly before coming to our laboratory in the early 1980s [1, 2]. Working Tomio Tada and his colleagues in Chiba University (Japan), Kyoko recognized that a rare B cell sensitive to killing with anti-CD5 plus complement played a key role in the carrier-specific suppression of antibody responses that Dr. Tada’s laboratory had discovered. On arriving at Stanford, Kyoko wanted to continue her work with this mysterious CD5+ B cell. However, she was also excited about joining Randy Hardy and David Parks in putting David’s newly-built dual-laser fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) to work on biologically relevant problems. Merging the two projects, Kyoko argued successfully for regular inclusion of anti-CD5 in stain sets designed to detect splenic B cells, and was regularly, if minimally, rewarded by the regular detection of a vanishingly small B cell subset that expressed IgM together with very low levels of CD5.

The next break (to my recollection) came when Ann Cooke, who was visiting from London, suggested that we look for the CD5+ B cells among the lymphocytes in the mouse peritoneal cavity (PerC) and, in particular, that we look in the PerC from NZB and related mouse strains. The rest, as they say, is history. By finding rich sources of B-1a cells (hereafter, “B-1a”), we were able to phenotypically characterize these unusual B cells; and by recognizing them in well-known autoimmune mice, we and others were able to link them to autoantibody and natural antibody production. Additional studies introduced B-1a as players in genetically-controlled murine immune deficiencies, and evidence demonstrating CD5 expression on mouse neoplasms introduced B-1a as sources of some of the well-known murine B lymphomas. Finally, the demonstration that human B-CLL commonly express CD5 opened the question of whether/how B-1a play a role in the human B cell economy.

Although much had still to be learned, these seminal findings were largely in place by the time of the first large B-1a meeting, which took place in 1991 in Florida and was supported by the New York Academy of Sciences.[3] Attended by a large community of investigators, the meeting met in plenary session to decide on a commonly acceptable terminology (B-1a, B-1b, B-2), which was agreed upon and reported by a long lista of signers in Immunology Today [3, 4], a periodical that was widely read at the time. The proceedings of the meeting, published in Annals New York Academy of Sciences,[3] present an extensive snapshot of B-1a properties at the time and served, much as we expect this current volume to serve, as a contemporary but long-lived resource for those interested in mouse and human B cells in biology and medicine.

B-1a today

One cannot help but wonder about the more than 20-year gap between the first B-1a meeting and the second one, which occurred June 16–19, 2014 in New York. There is no simple answer to why this hiatus occurred. In part, it occurred because B cells studies, particularly B-1a studies, basically went out of fashion, and funding followed investigator movement into other areas (or vice versa). Sadly, however, there is also good reason to believe that fear of controversy, particularly in times of weak funding, drove many laboratories away.

Admittedly, the idea that B-1a belong to a distinct developmental lineage was, and for some still is, anathema. However, the evidence favoring some form of a dual (or multiple) lineage model has continued to grow, as has the number of investigators open to considering or adopting it in some form.

Crafting this opening message for the 2014 B-1 cell conference has proven a daunting task, given all of the “water that has flowed under the bridge” since the 1991 conference. However, with the license granted to those who introduce conferences and are charged with providing a 20,000 foot view of the past, present and future, I will venture a brief creative and somewhat personal view of B-1a developmental and functional mechanisms. Hopefully, this message will help to kick off a much greater exchange of ideas of how the immune system evolved, how it operates, and the role(s) that B-1a and other cells play in the immune system as a whole.

Layered evolution as a formative force in the mammalian immune system

In an invited mini-review published in Cell in 1989 [5], we (Len Herzenberg and I) suggested that the progressive evolution of the immune system is “recorded” in the developmentally and functionally distinct B cells that together populate and constitute the B cell compartments in the mouse. At the time (and for some years thereafter), the idea that B-1a and B-2 cells do not both descend from the typical HSC in adult bone marrow was clearly heretical. But perhaps surprisingly to those who initially dismissed this model, evidence that continued to accumulate over the years has proven remarkably consistent with the dual lineage concept.[6–18] Today, some twenty-five years later, our recent single HSC transfers studies have directly and unequivocally demonstrated that HSCs sorted from adult BM (BM HSCs) give rise to B-2 but not B-1a in adoptive recipients.[14]

At present, several laboratories (including our own) are actively working to determine when B-1a and B-2 progenitors diverge. Preliminary studies trace this lineage separation to early embryonic/fetal life, showing that some time prior to development of the 10 day old fetus, progenitors for B-1a split from the pathway that gives rise to HSCs. These findings are quite consistent with IgH sequencing evidence demonstrating that B-1a and B-2 pre-immune IgH repertoires are quite distinct,[6] as are the cytokine profiles expressed by B-1a and B-2 cells. [19]

The antibodies that B-1a produce also tend to target different antigens than the antibodies produced by B-2 cells. In addition, the kinetics and other properties of the responses also tend to be quite different. B-2 cells produce the classical T-dependent and germinal center–dependent IgM and high affinity IgG antibody responses that text books commonly treat as indicative of all antigen-stimulated antibody responses. B-1a, in contrast, are well known as producers of so-called natural antibody “responses”, which initiate during fetal or neonatal life and are detectable in serum as long-term “constitutive” IgM and/or IgG antibodies that react with self and/or microbial antigens.

B-1a, however, are not restricted to producing natural antibodies. They are well known to produce antigen-stimulated IgM and IgG antibody responses to certain antigens, including T-dependent and T-independent responses to phosphorylcholine (PC), depending on the form in which the antigen is presented. In addition, they can be induced to produce antibodies specific for widely disparate antigens, e.g., influenza virus [20] and the dinitrophenyl hapten, [1, 2] particularly when presented on a bacterial carrier (e.g., Brucella abortus).

Our recent studies (led by Yang Yang) [21–23] show that a glycolipid (FtL) isolated from Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (Ft LVS) readily stimulates B-1a to produce IgM and IgG antibodies that are reactive with the immunizing antigen. B-2 cells, in contrast, do not produce detectable anti-FtL responses.

FtL immunization also induces long-term protection against lethal infection with Ft LVS. [21–23] This includes the generation of B-1a FtL-specific memory cells capable of producing IgM and IgG antibody responses.[22] The memory cells are induced in the spleen but migrate very rapidly to the peritoneal cavity, where they remain for the life of the animal, migrating back to spleen and generating antibody responses only when the animal is re-stimulated with the priming antigen under appropriate conditions.[21–23]

The kinetics of the B-1a anti-FtL response in serum clearly distinguishes it from typical antigen-stimulated B-2 primary and memory responses. FtL priming induces a brief burst of anti-FtL production, mainly IgM, but including some IgG. The antibody responses peak about seven days after immunization, after which serum anti-FtL titers begin to fall. By day 21, serum anti-FtL titers settle at a very low level that nonetheless remains clearly above the background levels of non-immunized mice. These low levels persist for the rest of the life of the immunized animal without subsequent boosting.

Curiously, priming with FtL plus adjuvant is less effective than priming with the FtL alone. However, boosting with FtL plus adjuvant is required to induce detectable secondary anti-FtL responses in serum.[21–23] But don’t be fooled; despite this minimal serum antibody response to boosting with FtL alone, the primed animals remain resistant for life to lethal infection with the pathogen.

To summarize: unlike antigens that target B-2 cells, for Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain glycolipid that targets B-1a, priming together with adjuvant decreases the antibody response relative to priming with antigen alone. Even more importantly, boosting with the antigen alone induces rapid division of antigen-specific B-1a memory in the PerC (their normal reservoir), but does not induce their migration to spleen, where they can differentiate to specific antibody producing plasma cells. To induce the secondary antibody production, the animal must be stimulated with the antigen together with adjuvant. Thus, if the secondary antigenic stimulation is not accompanied by adjuvant, the antibody titer in serum will not rise, and the priming by the vaccine or antigen under test will appear to have been unsuccessful.

Vaccine development

Our findings with Ft LVS glycolipid immunization [21–23] clearly have very important implications for vaccine development strategies. Current theory takes the view that the adequacy of priming with a pathogen-derived antigen (usually plus adjuvant) will be reported by the secondary antibody response produced following a typical boost (soluble antigen, no adjuvant) with the antigen. This strategy would completely fail to demonstrate that priming with FtL induced long-term protective immunity to the antigen.

I cannot help but wonder whether the curious properties of B-1a responses have not confounded many studies in which investigators assumed, in accord with prevailing views, that it is safe to extrapolate from what is known about B-2 cell responses to define expectations for responses produced by B-1a. How many potential vaccines have been rejected due to testing with a strategy that was inadvertently, but nonetheless inappropriately, tailored to reveal responses to antigens that stimulate B-2 rather than B-1a responses? And how many lives could we save by extending vaccine screening methods to include protocols that would trigger and reveal memory responses produced by B-1a?

Regenerative medicine

While we are considering how attention to B-1a functions might impact important treatment protocols, perhaps we should be thinking about regenerative medicine and use of BM HSCs to replenish elements of a therapy-depleted lymphoid compartment. Studies from our laboratory (notably by Eliver Ghosn) and elsewhere have shown that although murine HSCs isolated from adult sources readily replenish B-2 cells in a lymphoid-depleted animal, they fail restore B-1a, [13, 14, 16–18] which are among the earliest lymphoid cells to appear and are largely known thus far to mainly be replenished by progenitors (stem cells?) obtained from fetal or neonatal sources.

These findings, which lay the groundwork for full identification and medical utilization of B-1a as a separate lymphoid lineage with distinctive lymphoid functions, will be the focus of publications that can be expected in the next year or two. For now, they remain “a gleam in my eye”, the fruition of a dream to which Len and I and the 1991 B-1a conference gave voice years ago (Fig. 1), and the fascination of the future that we collectively in the B cell community will build in years to come.

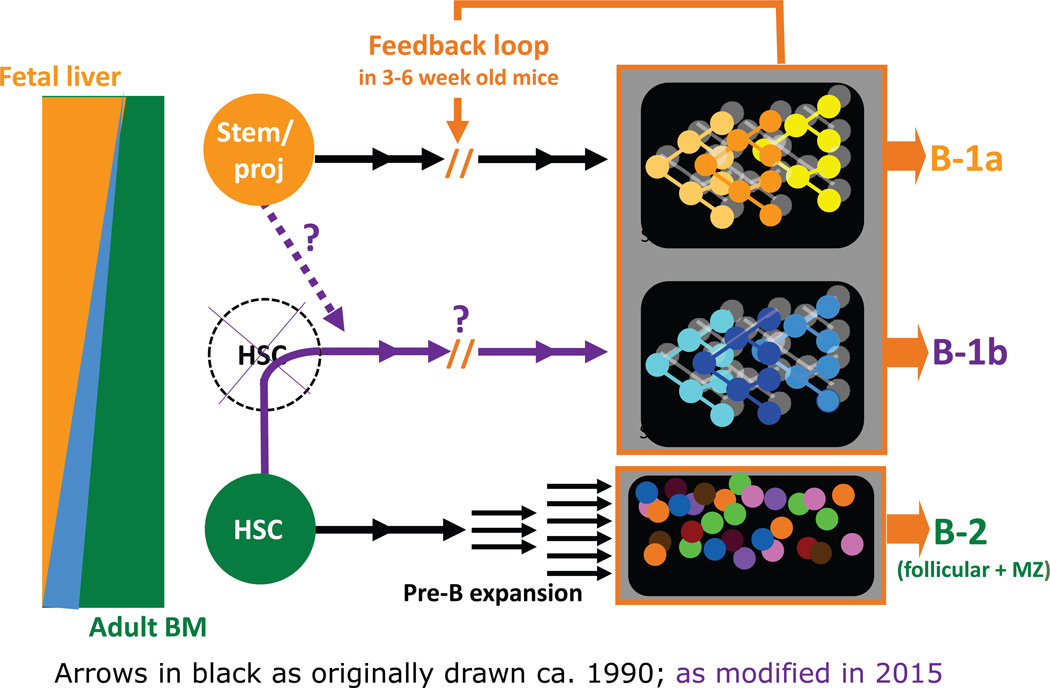

Figure 1.

Multi-lineage model of B cell development - ca. 1990. This early B cell development model has held up pretty well. At the time, we envisioned B-2 cells as arising from HSCs, and B-1a and B-1b cells as distinct lineages arising early from unknown stem or other cells. Current data are consistent with this construction except for B-1b cells, which our latest data indicate are at least partially derived from HSCs.

Acknowledgments

There are many people to thank for enabling this meeting and the publication in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences resulting from it. The conference organizers, Thomas Rothstein, Nichol Holodick, Eliver Ghosn and I, offer our special appreciation to The Feinstein Institute for enabling this meeting, and to the New York Academy of Sciences for publishing this and the preceding volume of discussions centered around B-1a. At a personal level, I am pleased to have the opportunity to thank John Mantovani, our laboratory administrative assistant, for the help he generously gave in the organization of this meeting and the organization of me so that I could attend and enjoy it. John and Eliver also provided much appreciated help in organizing the details of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Anthony Allison, Fred Alt, Larry Arnold, Susan Astin, Gail Bishop, Paulo Casali, Stephan Clarke, Max Cooper, Antonio Coutinho, Wendy Davison, Hua Gu, Richard Hardy, Geoffrey Haughton, Leonore Herzenberg, Leonard Herzenberg, Maureen Howard, Koichi Ikuta, Aaron Kantor, John Kearney, Paul Kincade, Norman Klinman, Thomas Kipps, Tadamitsu Kishimoto, John Kehrl, Georges Kohler, Marian Koshland, Frans Kroese, Gary Litman, Peter Lydyard, Miguel Marcos, Michael McGrath, Cesar Milstein, Paola Minoprio, Garry Nolan, Gustav Nossal, Anne O'Garra, Jane Parnes, Christine Plater-Zyberk, Klaus Rajewsky, Elizabeth Raveche, Michael McGrath, Toshikazu Shirai, Nanette Solvason, Alan Stall, Kiyoshi Takatsu, Norman Talal, Phillip Tucker, Meenal Vakil, Thomas Waldschmidt, Jean-Claude Weill, and lsaac Witz.

References

- 1.Hayakawa K, et al. The "Ly-1 B" cell subpopulation in normal, immunodefective, and autoimmune mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1983;157(1):202–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayakawa K, et al. Ly-1 B-Cells - Functionally Distinct Lymphocytes That Secrete Igm Autoantibodies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America-Biological Sciences. 1984;81(8):2494–2498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herzenberg LA, Haughton G, Rajewsky K, editors. CD5 B Cells in Development and Disease. Proceedings of a conference. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;651:1–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantor A. A new nomenclature for B cells. Immunol Today. 1991;12(11):388. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90135-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Toward a layered immune system. Cell. 1989;59(6):953–954. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90748-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantor AB. The development and repertoire of B-1 cells (CD5 B cells) Immunol Today. 1991;12(11):389–391. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90136-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzenberg LA, Kantor AB, Herzenberg LA. Layered evolution in the immune system. A model for the ontogeny and development of multiple lymphocyte lineages. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;651:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroese FG, et al. A dual origin for IgA plasma cells in the murine small intestine. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;371A:435–440. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1941-6_91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tung JW, Herzenberg LA. Unraveling B-1 progenitors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(2):150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tung JW, et al. Phenotypically distinct B cell development pathways map to the three B cell lineages in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(16):6293–6298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511305103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tung JW, et al. Identification of B-cell subsets: an exposition of 11-color (Hi-D) FACS methods. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;271:37–58. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-796-3:037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells SM. Development of B Cell Subsets. In: Honjo T, Alt F, Alt F, editors. Immunoglobulin Genes. London: Academic Press Limited; 1995. pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosn EE, et al. Distinct progenitors for B-1 and B-2 cells are present in adult mouse spleen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):2879–2884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019764108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghosn EE, et al. Distinct B-cell lineage commitment distinguishes adult bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(14):5394–5398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121632109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghosn EE, et al. CD11b expression distinguishes sequential stages of peritoneal B-1 development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(13):5195–5200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712350105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montecino-Rodriguez E, Dorshkind K. B-1 B cell development in the fetus and adult. Immunity. 2012;36(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorshkind K, Montecino-Rodriguez E. Fetal B-cell lymphopoiesis and the emergence of B-1-cell potential. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(3):213–219. doi: 10.1038/nri2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshimoto M, et al. Embryonic day 9 yolk sac and intra-embryonic hemogenic endothelium independently generate a B-1 and marginal zone progenitor lacking B-2 potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(4):1468–1473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015841108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan B, Morel L. Role of B-1a cells in autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5(6):403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baumgarth N, et al. B-1 and B-2 cell-derived immunoglobulin M antibodies are nonredundant components of the protective response to influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2000;192(2):271–280. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole LE, et al. Antigen-specific B-1a antibodies induced by Francisella tularensis LPS provide long-term protection against F. tularensis LVS challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(11):4343–4348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813411106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, et al. Antigen-specific memory in B-1a and its relationship to natural immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(14):5388–5393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121627109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, et al. Antigen-specific antibody responses in B-1a and their relationship to natural immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(14):5382–5387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121631109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]