Abstract

The T box transcription antitermination riboswitch controls bacterial gene expression by structurally responding to uncharged, cognate tRNA. Previous studies indicated that cofactors, like the polyamine spermidine, might serve a specific functional role in enhancing riboswitch efficacy. Since riboswitch function depends on key RNA structural changes involving the antiterminator element, the interaction of spermidine with the T box riboswitch antiterminator element was investigated. Spermidine binds antiterminator model RNA with high affinity (micromolar Kd) based on isothermal titration calorimetry and fluorescence-monitored binding assays. NMR titration studies, molecular modeling and inline and enzymatic probing studies indicate that spermidine binds at the 3′ portion of the highly conserved seven-nucleotide bulge in the antiterminator. Together, these results support the conclusion that spermidine binds the T box antiterminator RNA preferentially in a location important for antiterminator function. The implications of these findings are significant both for better understanding the T box riboswitch mechanism and for antiterminator-targeted drug discovery efforts.

Keywords: RNA, Riboswitch, Drug discovery, Spermidine, Transcription, T box, Antiterminator, RNA Binding

Introduction

The T box transcription antitermination regulatory mechanism is found primarily in Gram-positive bacteria, including many pathogens (1–4). Regulation of gene transcription occurs by the riboswitch recognizing and structurally responding to levels of uncharged tRNA (4). The tRNA anticodon binds a specifier sequence in the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of the nascent mRNA, thus providing specificity while the uncharged tRNA acceptor end base pairs with the first four nucleotides at the 5′ portion of the bulge of a highly conserved antiterminator element in the 5′-UTR (4). This tRNA-antiterminator base pairing creates a stable complex that prevents formation of a competing terminator structure. In the absence of this base pairing, the competing terminator element forms preferentially and transcription terminates prematurely (4). Biophysical studies of the specifier domain (5), antiterminator element (6, 7), and of tRNA interacting with 5′-UTR model RNAs and sub-elements including the antiterminator (8–14) have provided insights in to structural details of the T box riboswitch. In addition, recent biochemical studies have provided evidence for T box riboswitches that regulate translation initiation (15).

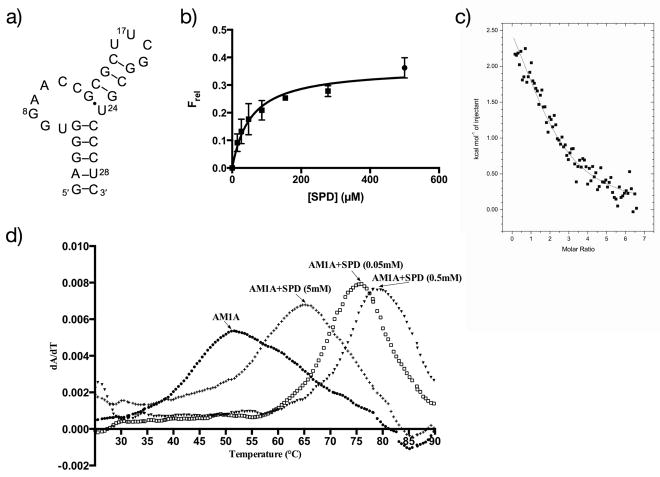

As part of a comprehensive drug discovery study, we have been investigating the structure, function and molecular recognition features of the T box antiterminator RNA. Targeting noncoding RNA, including other riboswitches, is a relatively new area of drug discovery (16–21). The antiterminator model RNA, AM1A (Figure 1a) is a functionally relevant model of the highly conserved bulge and stem regions of the T box antiterminator, with a well-characterized tetraloop (UUCG) substituted for the nonconserved apical loop (6). AM1A binds tRNA in a functionally relevant manner (6, 8), facilitated by Mg2+ (9, 22), and is functional in vivo (23). The seven-nucleotide bulge induces a significant bend between the two flanking helices in AM1A (7) and binds polycationic ligands, such as aminoglycosides, in a structure-specific manner (24, 25). Less highly charged ligands have been identified which specifically bind AM1A (26–32) and affect T box transcription antitermination in vitro (33) indicating that the antiterminator element function is susceptible to modulation by small molecules.

Figure 1.

AM1A and spermidine binding. a) secondary structure of antiterminator model RNA AM1A, b) binding isotherm for spermidine (SPD) binding to 5′-TAMRA-AM1A, c) representative processed ITC data for spermidine binding to AM1A (extensive titration, see Results for details), d) UV-monitored thermal denaturation of AM1A in the presence of increasing concentrations of spermidine where dA/dT is the first derivative of the absorbance at 260 nm. Arrows point to the Tm of the relevant dataset for AM1A with 0.05, 0.5 and 5 mM spermidine as indicated and with no spermidine.

Polyamines, including spermidine (N-(3-aminopropyl)-1,4-butanediamine), bind to RNA through electrostatic interactions (34). However, rather than being purely a nonspecific interaction, there is strong evidence that functionally important, selective structural changes occur upon binding of spermidine to bulged regions of RNA (35) and that polyamines can bind nucleic acids with base specificity (36). Previous studies with the T box riboswitch found that spermidine significantly stimulated transcription readthrough (antitermination) in vitro (37). This enhanced readthrough efficacy occurred both with and, to a lesser extent, without tRNA, strongly implicating that spermidine might be binding the antiterminator and affecting its function (38). In this study, we investigate the binding of spermidine to T box antiterminator model RNA to determine if there is a structure-specific interaction. A better understanding of molecular interactions between spermidine and the antiterminator, the key structural element that enables readthrough, will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the T box riboswitch mechanism and aid in the design of novel, T box antiterminator-targeted antibacterial compounds.

Methods and Materials

Antiterminator model RNA AM1A consists of 5′-GAGGGUGGAACCGCGCUUCGGCGUCCCUC-3′ (6, 7). Fluorescently labeled 5′-Carboxyrhodamine-AM1A-3′-Black Hole Quencher 2 (ROX-AM1A-BHQ2) was obtained from Trilink Biotechnologies Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA) and prepared for use as previously described (31). Fluorescently labeled 5′-TAMRA-AM1A was obtained from ThermoScientific, Inc. (Lafayette, CO, USA). Unlabeled AM1A was prepared by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase as previously described (22) and dialyzed prior to use. Spermidine was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO).

Kd determination

5′-TAMRA-AM1A was dialyzed and renatured prior to use in 10 mM MOPS, pH 6.5, 0.01 mM EDTA. The binding isotherm was obtained by monitoring spermidine induced changes in the fluorescence of 5′-TAMRA-AM1A using the method described previously (8, 39). Each binding reaction consisted of 5′-TAMRA-AM1A (100 nM) in 50 mM MOPS, pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.01 mM EDTA and a range of spermidine concentrations. Ten minutes after spermidine addition, the fluorescence was measured using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) with λex = 554 nm and λobs = 595 nm. The relative fluorescence was calculated using Frel = |F-F0|/F0 where F is the fluorescence at 595 nm in the presence of ligand and F0 is the fluorescence in the absence of ligand. The binding isotherm for replicate experiments was constructed by plotting Frel vs. spermidine. Single-site and two-site binding model fits were compared using Prism (Graphpad).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

ITC measurements were performed at 25 °C on a MicroCal ITC200 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) in 50 mM MOPS, pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.01 mM EDTA. AM1A was dialyzed against this buffer prior to use, and spermidine was dissolved in the same buffer to ensure identical buffer conditions for the titrant and titrate. Duplicate experiments consisted of titrating 750 μM spermidine (titrant) into 50 μM AM1A (titrate) over 39 titrations (1 μL per titration, 240 s between each titration, with 1,000 rpm stir speed). A background measurement was obtained by titrating 750 μM spermidine into buffer (with no RNA) using the same conditions. Following subtraction of the background, experimental data were fit using the MicroCal Origin 7.0 software (40) with a comparison of one-site, two-site and sequential binding models while varying the stoichiometry (n = 1–3). An extensive titration experiment (and corresponding background) was also performed under identical conditions by titrating 1500 μM spermidine in to 50 μM AM1A over 78 titrations (0.5 μL each).

Thermal Denaturation

For the UV-monitored thermal denaturation studies, AM1A RNA was dialyzed in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5, 0.01 mM EDTA and renatured prior to use. Each thermal denaturation reaction consisted of AM1A (0.7 μM) and spermidine (0–5 mM). UV monitored thermal denaturation data were obtained as previously described (6) using a Beckman Coulter 640 UV/Vis spectrometer equipped with a peltier, temperature-controlled cell holder. The first derivative of the absorbance at 260 nm (dA/dT) vs. temperature was calculated using OD-Deriv (41) where the temperature corresponding to the maximal peak value represents the melting temperature, Tm. For fluorescently monitored thermal denaturation studies, ROX-AM1A-BHQ2 was used as previously described (31). Each thermal denaturation reaction consisted of 100 nM ROX-AM1A-BHQ2 in 10 mM sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, 10 μM EDTA with spermidine (0–15 mM). The fluorescence (λex = 585 nm, λobs = 610 nm) was monitored with increasing temperature as previously described (31).

Inline and Enzymatic probing

For all probing studies, AM1A was labeled with 32P using Ambion® KinaseMax™ 5′ end-labeling kit from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). For probing with RNaseA, the 5′-32P-AM1A was incubated in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2 with spermidine (0–7 mM) and RNase A (0.02 μg/mL) for 15 min at room temperature. Denaturing loading buffer was added to stop the reaction (final concentration: 4 M Urea, 0.45 mM EDTA). The cleavage products were separated on a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (19:1 acrylamide : bis-acrylamide), followed by autoradiography. The same procedure was followed for RNase T1 probing with the exception that the concentration of RNase T1 was 0.02 U/μL. For Mg2+ facilitated (inline) cleavage probing (42), 5′-32P-AM1A was incubated for 40 hrs at room temperature in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 100 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2 with spermidine (0–5 mM for specific binding slope analysis; 10–40 mM for nonspecific binding analysis) followed by gel separation and autoradiography. For all probing studies, the relative normalized band intensities of the autoradiograph were determined using Nucleo Vision (Nucleotech) and plotted against ligand concentration to determine the slope for ligand-induced relative band intensity changes as previously described (29, 32).

NMR titrations

Imino proton NMR spectra were obtained on a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer using the Varian Jump-Return pulse sequence optimized for suppression of the water (H2O) resonance. All spectra were obtained at ambient room temperature (~23 °C). AM1A (1.3 mM) in 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5, 0.001 mM EDTA, containing 10% D2O, was renatured prior to use as previously described (7). Each titration addition consisted of adding 0.6 μL of a concentrated aqueous spermidine stock solution to obtain the spermidine:AM1A final molar ratios indicated.

Docking studies

Spermidine structures were built as separate files in Spartan (Wavefunction Inc.). Separate global energy minimizations at the ground state were performed using molecular mechanics with MMFF, Semi-Empirical AM1 and Hartree-Fock 3–21G in vacuum. Total charges were indicated as neutral, cation, dication, and 3 for the non-protonated, mono-protonated, di-protonated and tri-protonated forms respectively. The minimized spermidine structures were then exported as mol2 files to Macromodel (Schrödinger, Inc.) and docked using the Glide module of First Discovery 2.7 (Schrödinger, Inc.) as previously described (29). Spermidine structures were docked to the NMR-derived solution structure of AM1A (PDB ID = 1N53) (7) and the 20 lowest energy poses for each starting structure were retained for analysis. Images of the resulting docked structures were rendered using Maestro 9.3.5 (Schrödinger, Inc.).

Results

Binding affinity and thermodynamics

Spermidine affinity for antiterminator model RNA AM1A (Figure 1a) was initially investigated using a fluorescence-monitored binding assay (8). Single- and two-site binding models were compared and the data best fit single-site binding with an observed Kd value of 54 ± 12 μM (Figure 1b). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was then used to investigate the thermodynamics of spermidine binding to AM1A. For both the regular and extensive titrations, the data best fit the one-site binding model with a stoichiometry of N = 2 indicating that there are possibly two binding sites with similar binding thermodynamics. Sequential binding and higher stoichiometry models resulted in poor fits. Representative data are shown in Figure 1c. The average of replicate experiments from the shorter titrations resulted in a Ka = 7.3 × 103 ± 0.2 × 103 M−1 (corresponding to Kd = 137 ± 3 μM) with ΔH = 5.7 ± 0.4 (kcal/mol) and ΔS = 37 ± 2 (cal/mol/K). The more extensive titration resulted in a slightly higher affinity (Ka = 1.6 × 104 M−1) with the best fit stoichiometry unchanged (N = 2), indicating no additional binding is occurring at the molar ratios assayed.

Spermidine effect on AM1A stability

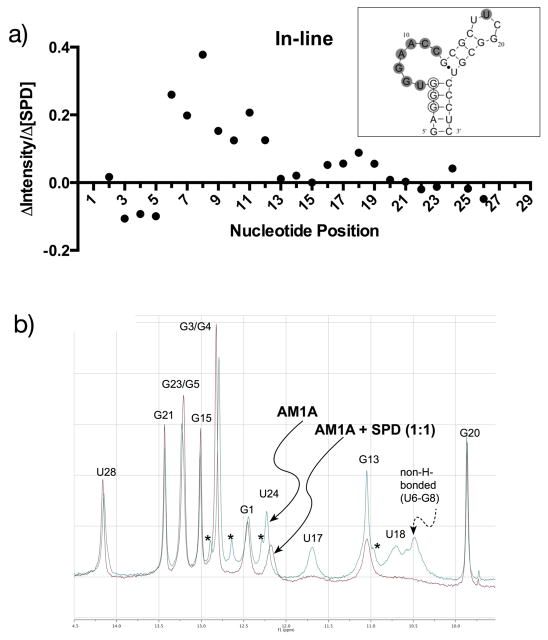

Ligand-induced changes in RNA stability are a useful method for characterizing ligand-RNA interactions (22, 31). The effect of spermidine on AM1A stability was investigated by UV-monitored thermal denaturation (43) (Figure 1d) and fluorescently-monitored thermal denaturation (31) (Supplementary Data). Both studies indicate that low concentrations of spermidine stabilize AM1A, but at high concentrations (> 5 mM), the structure of AM1A is destabilized relative to the stability observed at < 5 mM. The inline cleavage studies, which detect flexible single-stranded and denatured RNA (42, 44), indicated a significant increase in susceptibility to inline cleavage across the entire AM1A sequence at spermidine concentrations > 5 mM (Supplementary Data) consistent with a non-specific denaturation at higher concentrations. In contrast, at lower concentrations of spermidine (< 5 mM), the most significant increased cleavage was observed in the bulge (U6-C12) region, consistent with a more localized interaction that altered conformational flexibility (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Identification of spermidine binding location. a) inline cleavage patterns of AM1A indicated by plot of slope values of spermidine (0–5 mM) concentration-dependent cleavage with inset of AM1A secondary structure summary of increased (filled circle) and decreased (open circle) cleavage locations, b) imino proton region of 1H-NMR (500 MHz) AM1A spectrum in the absence and presence of 1 equivalent of spermidine (SPD). Starred peaks arise from minor alternate conformation of AM1A.

Localized binding

The most significant changes to inline cleavage susceptibility with spermidine (0–5 mM) were focused in the bulge region (Figure 2a), as were the changes in enzymatic cleavage by RNase A and RNase T1, especially at the 3′ portion of the bulge and G13 (Supplementary Data). Also, titration of spermidine (up to a ratio of 1:1) resulted in the reduction or disappearance of imino proton peaks in the NMR spectra of AM1A for G13, U17, U18, G20, U24 and the non-hydrogen bonded nucleotides in the bulge (U6-G8) (Figure 2b and Supplementary Data). In addition, the imino proton peak for U24 shifted to a lower ppm value (i.e., shifted upfield). In contrast, little or no changes were observed for the remaining imino proton peaks in the stem regions of AM1A.

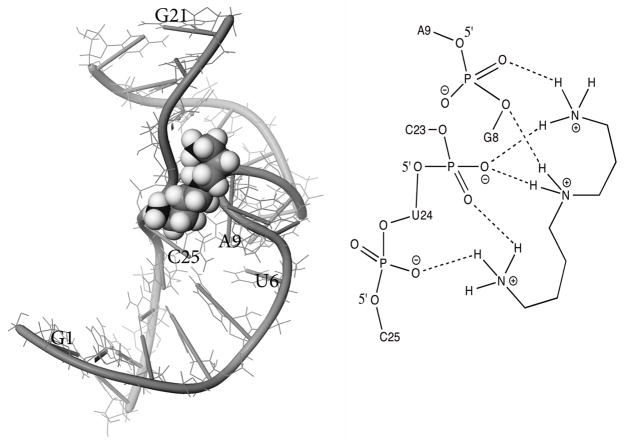

Spermidine-antiterminator model RNA complex

Molecular modeling docking studies were performed to provide some insight in to possible binding interactions. Spermidine exists predominantly in the tri-protonated form at pH 6.5 (45). However, all possible protonation states of spermidine were docked to AM1A to investigate the possibility that binding might occur via one of the other protonation states. Spermidine starting structures were minimized in Spartan using molecular mechanics with MMFF, semi-empirical AM1, or Hartree-Fock 3–21G (in vacuum) methods. These starting structures were then docked to the NMR-derived solution structure of AM1A (i.e., the stem and bulge regions) using Glide as in a previously described method (29).

The triprotonated spermidine bound with the lowest Emodel binding energy (best binding) regardless of preparation method (Figure 3 and Supplementary Data). This binding energy became less favorable with fewer protonated nitrogens. The different energy minimization strategies for preparing the starting structures resulted in no significant structural differences in the lowest energy tri-protonated spermidine-AM1A complex nor in the average of the Emodel values for the 20 lowest energy poses (Supplementary Data). This indicates that the calculation method chosen for the preliminary energy minimization of the starting structure geometries is likely not biasing the docking results. In the lowest energy docked structure, tri-protonated spermidine bound AM1A at the 3′ portion of the bulge with interactions between the protonated amino groups and phosphate backbone oxygens of G8 and U24 consistent with electrostatic binding (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Glide-derived docked structure and major contacts for triprotonated spermidine (rendered in space-filling model) binding to AM1A (numbering corresponds to that shown in Figure 1a., with phosphate backbone and nucleotide bases highlighted with tubes). The semi-empirical preparation method was used for the spermidine (see Results).

Discussion

Spermidine is known to bind noncoding RNA in single-stranded regions and affect its function (35). In vitro transcription studies have shown that spermidine enhances T box riboswitch readthrough (antitermination) efficacy (37) in a manner that is not entirely dependent on tRNA (38). Since the antiterminator element is directly involved in the switch from transcription termination to readthrough, it is possible that spermidine may be interacting with the antiterminator. To explore this possibility further, the molecular interactions between spermidine and T box antiterminator model RNA were investigated.

ITC has been used extensively for studying RNA-ligand interactions (46), but interestingly, there are few calorimetric studies of polyamines binding to RNA (47, 48). The spermidine binding affinity for AM1A determined by ITC (μM Kd) is similar to the affinity determined by the fluorescence-monitored binding assay (Figure 1). The thermodynamic parameters obtained for the system indicated a small positive enthalpy with a significant entropic component. This observed entropically-driven endothermic binding could be due to the enthalpic penalty and increased entropy associated with release of water molecules from the solvated spermidine upon binding to the RNA. Calorimetric studies with larger structured RNAs have shown that polyamine binding-induced stabilization was not always correlated with favorable enthalpies (48). In addition, an increase in flexibility of the bulge nucleotides (consistent with the NMR and inline probing studies) could be a contributing factor to increased entropy and endothermic binding since the bulge region of uncomplexed AM1A has previously been shown to have extensive base stacking interactions (7). Despite this localized increase in flexibility, however, the net effect of spermidine binding is to stabilize the overall secondary structure of the antiterminator model RNA based on the UV- and fluorescently-monitored thermal denaturation studies. These results are consistent with the previously observed enhancement of T box transcription readthrough efficacy by spermidine that occurs even in the absence of tRNA (38), since stabilization of the antiterminator element during transcription would enhance readthrough. At higher concentrations of spermidine (> 5mM), however, destabilization of the antiterminator model RNA occurs as indicated by a switch to decreasing Tm and a non-specific enhancement in inline cleavage across the entire RNA. These results are consistent with polyamine-RNA studies which identified non-specific destabilization at higher concentrations (49) and are also consistent with the switch to decreased T box transcription readthrough efficacy observed at > 5 mM spermidine (38).

In the NMR-derived solution structure of AM1A, the seven nucleotide bulge is characterized by extensive stacking of A9-C12 that induces a kink between the two flanking helical stem regions (7). Useful information regarding ligand binding location can be obtained by monitoring changes in the imino proton region of the AM1A 1H NMR (32). Localized changes in the imino proton NMR of AM1A (Figure 2) provide compelling evidence for a preferential binding location at low concentrations of spermidine (< 5 mM). The disappearance of imino proton peaks for the bulge and loop nucleotides with virtually no change in the stem regions, indicate that spermidine may preferentially bind the single-stranded regions of AM1A and alter its conformational flexibility (thus affecting the imino proton exchange rates). This is consistent with the significant enhancement in inline cleavage localized in the bulge region at < 5mM spermidine. Spermidine also appears to interact with the tetraloop (U17-G20) based on the decrease in imino proton peak intensities and increased inline cleavage, but these effects are less pronounced than with the bulge nucleotides and no imino proton chemical shift changes were observed. The tetraloop is not part of the highly conserved T box antiterminator element (6), however, a second spermidine localization in AM1A is consistent with the ITC data, which indicated a binding stoichiometry of 2.

A decrease in imino proton peak intensity for both G13 and U24, coupled with the distinct upfield shift of U24 strongly suggests that spermidine may bind the nucleotides corresponding to the 3′ portion of the bulge and affect the local environment of the G13•U24 base pair. Previous studies identified the 3′ portion of the bulge as a diffuse binding site for Mg2+ (22), indicating that this region of AM1A may be predisposed to cationic binding. The enzymatic cleavage assay results are consistent with this binding site since the most significant spermidine-induced decrease in cleavage occurred at the bulge nucleotides, especially at the 3′ portion of the bulge and G13. The decreased cleavage could be due to spermidine binding these nucleotides and blocking nuclease access, altering cleavage susceptibility due to spermidine-induced conformational changes, or a combination of both.

Previous docking studies with a variety of ligands have provided useful complementary information regarding T box antiterminator ligand binding (29, 32). Molecular modeling studies docking spermidine to the NMR-derived solution structure of AM1A are consistent with spermidine binding the 3′ portion of the bulge with an electrostatic interaction between the protonated amino groups and phosphate backbone oxygens of G8 and U24 (Figure 3). The docked binding site location is consistent with the spermidine-induced changes in the NMR titration and the inline and enzymatic probing studies at < 5 mM spermidine. The spermidine is inserted between the phosphate backbone of the bulge nucleotides and U24. In this location, spermidine may serve to shield the electrostatic repulsion between these non-A-form, close proximity phosphate groups. This binding site also spans an absolutely conserved A nucleotide (A10 in AM1A) the function of which is not fully understood (nor the reason for its absolute conservation) (1, 2, 4). While recent structural studies have provided insight in to tRNA-antiterminator binding interactions, the possible role of this absolutely conserved A nucleotide was not investigated (14). Since previous studies indicated that spermidine is likely mimicking a specific protein cofactor (37), it is possible that the putative protein cofactor might also bind at the 3′ portion of the bulge and form specific contacts with this absolutely conserved A. Interestingly, the spermidine binding site location is distinctly different from the binding sites for the small molecule leads identified in our drug discovery studies (29, 32).

Some insight regarding possible mode of binding can be drawn through comparison to aminoglycoside affinities. Aminoglycosides bind to AM1A in a structure-specific manner via electrostatic interactions (25) dependent on the number of basic amines (24). Since spermidine is triprotonated at pH 6.5 (45), its binding to AM1A may involve electrostatic interactions comparable to that of the aminoglycosides. The observed spermidine affinity for binding to 5′ fluorescently labeled AM1A is close to that observed for tobramycin (38 μM) and paromomycin (50 μM) (24). While tobramycin and paromomycin each have five amines, the dominant species of each is not expected to be fully protonated at pH 6.5 based on the known pKa values (50, 51). Consequently, the affinity of fully protonated spermidine for AM1A is indeed comparable to that of the partially protonated tobramycin and paromomycin, suggesting that spermidine may bind via electrostatics.

Conclusion

The experimental results indicate that spermidine at low concentrations (< 5 mM) binds at the 3′ portion of the seven-nucleotide bulge in T box antiterminator model RNA, alters local conformational flexibility, and stabilizes the overall structure. This binding is in the region of the antiterminator bulge that contains an absolutely conserved A nucleotide. Binding in the highly conserved antiterminator bulge, towards the portion that is not known to directly interact with tRNA, may provide an explanation for how spermidine enhances riboswitch transcription readthrough. The implications of this co-factor effect are significant for further understanding this complex regulatory mechanism and for drug discovery studies targeting the T box riboswitch antiterminator.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (GM073188, GM61048) for support of this work and H. Dawoud for assistance with sample preparation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None

Individual NMR titrations, molecular modeling preparation comparison and gel images are available as supplementary data.

Figure S1. Fluorescently monitored effect of spermidine on AM1A stability.

Figure S2. Inline cleavage probing of AM1A in the presence of spermidine.

Figure S3. AM1A NMR titration with spermidine.

Figure S4. Spermidine effect on enzymatic cleavage patterns

Figure S5. Summary of modeling methods.

References

- 1.Vitreschak AG, Mironov AA, Lyubetsky VA, Gelfand MS. Comparative genomic analysis of T-box regulatory systems in bacteria. RNA. 2008;14:717–35. doi: 10.1261/rna.819308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutierrez-Preciado A, Henkin TM, Grundy FJ, Yanofsky C, Merino E. Biochemical features and functional implications of the RNA-based T box regulatory mechanism. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:36–61. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00026-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green NJ, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. The T box mechanism: tRNA as a regulatory molecule. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(2):318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henkin TM. The T box riboswitch: a novel regulatory RNA that utilizes tRNA as its ligand. BBA-Gene Reg Mech. 2014;1839:959–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Henkin TM, Nikonowicz EP. NMR structure and dynamics of the specifier domain from the Bacillus subtilis tyrS T box leader RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3388–98. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerdeman MS, Henkin TM, Hines JV. In vitro structure-function studies of the Bacillus subtilis tyrS mRNA antiterminator: Evidence for factor independent tRNA acceptor stem binding specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(4):1065–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerdeman MS, Henkin TM, Hines JV. Solution structure of the B. subtilis T box antiterminator RNA: Seven-nucleotide bulge characterized by stacking and flexibility. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:189–201. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Means JA, Wolf S, Agyeman A, Burton JS, Simson CM, Hines JV. T box riboswitch antiterminator affinity modulated by tRNA structural elements. Chem Biol Drug Design. 2007;69:139–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2007.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Means JA, Simson CM, Zhou S, Rachford AA, Rack J, Hines JV. Fluorescence probing of T box antiterminator RNA: Insights into riboswitch discernment of the tRNA discriminator base. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389:616–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Co-crystal structure of a T-box riboswitch stem I domain in complex with its cognate tRNA. Nature. 2013;500(7462):363–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grigg JC, Chen Y, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM, Pollack L, Ke A. T box RNA decodes both the information content and geometry of tRNA to affect gene expression. PNAS. 2013;110(18):7240–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222214110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grigg JC, Ke A. Structural determinants for geomettry and information decoding of tRNA by T box leader RNA. Structure. 2013;21(11):2025–32. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grigg JC, Ke A. Sequence, structure, and stacking: specifics of tRNA anchoring to the T box riboswitch. RNA Biol. 2013;10(12):1761–4. doi: 10.4161/rna.26996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Direct evaluation of tRNA aminoacylation status by the T-box riboswitch using tRNA-mRNA stacking and steric readout. Mol Cell. 2014;55:148–55. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherwood AV, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM. T box riboswitches in Actinobacteria: Translational regulation via novel tRNA interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(4):1113–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424175112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chirayil S, Chirayil R, Luebke KJ. Discovering ligands for a microRNA precuror with peptoid microarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(16):5486–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulsen RB, Seth PP, Swayze EE, Griffey RH, Skalicky JJ, Cheatham TEI, et al. Inhibitor-induced structural change in the HCV IRES domain IIa RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:7263–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911896107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diegan KE, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Riboswitches: discovery of drugs that target bacterial gene-regulatory RNAs. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1329–38. doi: 10.1021/ar200039b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis DR, Seth PP. Therapeutic targeting of HCV internal ribosomal entry site RNA. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2011;21:117–28. doi: 10.3851/IMP1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lunse CE, Schuller A, Mayer G. The promise of riboswitches as potential antibacterial drug targets. Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;304:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warner KD, Homan P, Weeks KM, Smith AG, Abell C, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Validating fragment-based drug discovery for biological RNAs: lead fragments bind and remodel the TPP riboswitch specifically. Chem Biol. 2014;5:591–5. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jack KD, Means JA, Hines JV. Characterizing riboswitch function: Identification of Mg2+ binding site in T box antiterminator RNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:306–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grundy FJ, Moir TR, Haldeman MT, Henkin TM. Sequence requirements for terminators and antiterminators in the T box transcription antitermination system: disparity between conservation and functional requirements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(7):1646–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Means JA, Hines JV. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies of aminoglycoside binding to a T box antiterminator RNA. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2169–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anupam R, Denapoli L, Muchenditsi AM, Hines JV. Identification of neomycin B binding site in T box antiterminator model RNA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:4466–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Means JA, Katz SJ, Nayek A, Anupam R, Hines JV, Bergmeier SC. Structure activity studies of oxazolidinone analogs as RNA-binding agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16(13):3600–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.03.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acquaah-Harrison G, Zhou S, Hines JV, Bergmeier SC. Library of 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole analogs of oxazolidinone RNA-binding agents. J Comb Chem. 2010;12:491–6. doi: 10.1021/cc100029y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maciagiewicz I, Zhou S, Bergmeier SC, Hines JV. Structure activity studies of RNA-binding oxazolidinone derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Letters. 2011:4524–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orac CM, Zhou S, Means JA, Boehme D, Bergmeier SC, Hines JV. Synthesis and stereospecificity of 4,5-disubstituted oxazolidinone ligands binding to T-box riboswitch RNA. J Med Chem. 2011;54:6786–95. doi: 10.1021/jm2006904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou S, Acquaah-Harrison G, Bergmeier SC, Hines JV. Anisotropy studies of tRNA - T box antiterminator RNA complex in the presence of 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:7059–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.09.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou S, Acquaah-Harrison G, Jack KD, Bergmeier SC, Hines JV. Ligand-induced changes in T box antiterminator RNA stability. Chem Biol Drug Design. 2011;79:202–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou S, Means JA, Acquaah-Harrison G, Bergmeier SC, Hines JV. Characterization of a 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazole binding to T box antiterminator RNA. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;20:1298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anupam R, Bergmeier SC, Green NJ, Grundy FJ, Henkin TM, Means JA, et al. 4,5-Disubstituted Oxazolidinones: High affinity molecular effectors of RNA function. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3541–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bachrach U. Naturally occurring polyamines: Interaction with macromolecules. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005;6(6):559–66. doi: 10.2174/138920305774933240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higashi K, Terui Y, Suganami A, Tamura Y, Nishimura K, Kashiwagi K, et al. Selective structural change by spermidine in the bulged-out region of double-stranded RNA and its effect on RNA function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32989–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabir A, Kumar GS. Binding of biogenic polyamines to deoxyribonucleic acids of varying base composition: Base specificity and the associated energetics of the interaction. PLOS-One. 2013;8(7):e70510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Putzer H, Condon C, Brechemeier-Baey D, Brito R, Grunberg-Manago D. Transfer RNA-mediated antitermination in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3026–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng C, Zhou S, Bergmeier SC, Hines JV. Factors that influence T box riboswitch efficacy and tRNA affinity. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, Zeng C, Zhou S, Means JA, Hines JV. Fluorescence assays for monitoring RNA-ligand interactions and riboswitch-targeted drug discovery screening. Methods Enzymol. 2015;550:363–83. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Origin. ITC Data Analysis in Origin: Tutorial Guide (version 7.0) MicroCal, LLC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Draper DE, Gluick TC. Melting studies of RNA unfolding and RNA-ligand interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1995;259:281–305. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)59049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soukup GA, Breaker RR. Relationship between internucleotide linkage geometry and the stability of RNA. RNA. 1999;5:1308–25. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puglisi JD, Tinoco I., Jr Absorbance melting curves of RNA. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:304–25. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Regulski EE, Breaker RR. In-line probing analysis of riboswitches. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;419:53–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-033-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kimberly MM, Goldstein JH. Determination of pKa values and total proton distribution pattern of spermidine by Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance titrations. Anal Chem. 1981;53(6):789–93. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feig AL. Applications of isothermal titration calorimetry in RNA biochemistry and biophysics. Biopolymers. 2007;87(5–6):293–301. doi: 10.1002/bip.20816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barciszewski J, Bratek-Wiewiórowska MD, Górnicki P, Naskret-Barciszewska M, Wierwiórowski M, Zielenkiewicz A, et al. Comparative calorimetric studies on the dynamic conformation of plant 5S rRNA. I. thermal unfolding pattern of lupin seeds and wheat germ 5S rRNA, also in the presence of magnesium and sperminium cations. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(2):685–701. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.2.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terui Y, Ohnuma M, Hiraga K, Kawashima E, Oshima T. Stabilization of nucleic acids by unusual polyamines produced by an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. Biochem J. 2005;388(Pt 2):427–33. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ouameur AA, Bourassa P, Tajmir-Riahi HS. Probing tRNA interaction with biogenic polyamines. RNA. 2010;16(10):1968–79. doi: 10.1261/rna.1994310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Szilágyi L, Pusztahelyi ZS, Jakab S, Kovács I. Microscopic protonation constants in tobramycin. An NMR and pH study with the aid of partially N-acetylated derivatives. Carbohydrate Res. 1993;247:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(93)84244-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walter F, Vicens Q, Westhof E. Amionoglycoside-RNA interactions. Current opinion in chemical biology. 1999;3:694–704. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(99)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.