Abstract

Personalized medicine tumor boards, which leverage genomic data to improve clinical management, are becoming standard for the treatment of many cancers. This paper is designed as a primer to assist clinicians treating head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients with an understanding of the discovery and functional impact of recurrent genetic lesions that are likely to influence the management of this disease in the near future. This manuscript integrates genetic data from publicly available aCGH and NGS genetics databases to identify the most common molecular alterations in HNSCC. The importance of these genetic discoveries is reviewed and how they may be incorporated into clinical care decisions is discussed. Considerations for the role of genetic stratification in the clinical management of head and neck cancer are maturing rapidly and can be improved by integrating data sets. This article is meant to summarize the discoveries made using multiple genomic platforms so that the head and neck cancer care provider can apply these discoveries to improve clinical care.

Keywords: NGS technology, target genes, tumor heterogeneity, genetic complexity, personalized medicine, HNSCC

Introduction

In the last decade, we witnessed an unprecedented technological acceleration concerning genome studies. It resulted in the accumulation of scientific data on the molecular background of cancer. Beginning from the introduction of Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) [1] a tool allowing whole-genome screening of DNA copy number alterations and therefore the identification of unbalanced chromosomal aberrations in a single analysis was finally available to the scientific community. CGH was soon upgraded to array-CGH wherein representative fragments of the human genome in form of BACs (bacterial artificial chromosome) or oligonucleotides are immobilized on a slide (DNA arrays). This development marked the beginning of the “array era” in genome studies. It inspired further development that led to the introduction of microarray technologies aimed at measuring other genomic features including global gene or miRNA expression (expression arrays) but also DNA binding, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and DNA methylation [2]. Importantly, combination of these array technologies allowed simultaneous analysis of a genome on multiple levels – DNA, mRNA, miRNA, methylation etc. leading to novel findings like the identification of novel tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes involved in the development of human cancers [3].

Recently, the microarray-based platforms are rapidly replaced by next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. It announces a new era in genome studies. It is expected that NGS techniques will increasingly replace the array-based techniques with falling costs of sequencing the human genome, falling costs of data storage and the development of novel, user-friendly software for data analysis. NGS technologies can be used in standard sequencing experiments allowing sequencing millions of DNA bases in a single experiment (so called DNA re-sequencing). At present, NGS is usually limited to a set of genes of interest (targeted sequencing) or all coding sequences of the genome (exome sequencing), but is still rarely used for sequencing the whole human genome (whole genome sequencing – WGS) mainly due to the high costs of the experiment and the vast amount of produced data. Moreover, NGS techniques are applied for gene expression (transcriptome sequencing, RNA-SEQ) or methylation analyses (bisulfite sequencing) providing an ideal tool for cancer genetic studies.

In the last years, NGS-based studies have been carried out in order to characterize the molecular background of human cancers and elucidate molecular mechanisms contributing to oncogenesis, progression and metastasis. The accumulated sequencing data containing exome sequencing, expression and methylation have recently been deposited in public repositories like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Data Portal, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute or the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) and are freely available to the scientific community.

In this review, we will focus on novel findings on the genetics of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) obtained from aCGH and NGS studies as well as clinical implications of these disruptive genomic events. The very large majority of head and neck cancers are squamous cell carcinomas that arise in the mucosal linings of the upper aerodigestive tract. The predominant causes of HNSCC are smoking and excessive consumption of alcohol. Besides these chemical agents, also infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV) is a risk factor for head and neck cancer, particularly in the oropharynx. Early stage HNSCCs are treated by surgery with or without postoperative radiotherapy, and more advanced stage either by the combination of surgery and postoperative radiotherapy, chemoradiation: the combined application of systemic cisplatin with concomitant locoregional radiotherapy, or bioradiation: the systemic application of the anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab with concomitant locoregional radiotherapy. Biomarkers for personalized therapy in HNSCC are still lacking, and it is generally hoped that the molecular catalogue of HNSCC will provide these.

Here, we demonstrate novel oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (TSG) and the related signaling pathways delineated in HNSCC, discuss identified genetic differences in HPV positive and negative tumors and show potential future applications of NGS in diagnosis and personalized cancer treatment [4-6]. In our opinion there is a need to propagate contemporary molecular procedures and their potential among head and neck clinicians.

Discovery of new HNSCC related genes

Cancer is caused by the accumulation of genetic alterations within oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. This is especially true for tumors such as HNSCC where epithelial cells are subjected to long-term exposure to carcinogens present mainly in the cigarette smoke but also in alcohol, processed food, chewed tobacco or inhaled contaminated air. The consequences of such exposure of chromosomes in relation to HNSCC were presented in the genetic progression model by Califano et al. in 1996 [7]. The authors’ delineated chromosomal aberrations observed recurrently in HNSCC and correlated them with successive steps of carcinogenesis including hyperplasia, dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, tumor and metastasis. Later this model was complemented by the “patch-field-tumor” model that described the earliest changes [8]. By the end of the twentieth century a more detailed analysis was not possible for technical reasons. Recently, with the introduction of novel molecular techniques and lastly NGS, comprehensive analysis of the recurrently aberrant regions became available and resulted in the identification of target genes within these regions.

It is important to stress that NGS sequencing projects have confirmed prior published mutational data for HNSCCs and showed a typical mutational profile reported for tobacco-related tumors and molecular features characteristic for SCC histologies [9-11]. Here, we compiled data from multiple publicly available data sets using both the Oncomine 3.0 aCGH and NGS databases [12, 13] as well as data downloaded from cBioPortal to demonstrate the most common alterations in HNSCC (Table 1 and Figure 1) [14-17]. Previously identified genes found to be most frequently mutated in HNSCC included TP53 (up to 67.5% mutated cases), CDKN2A (up to 16.7% mutated and 27% deleted cases) and PIK3CA (16.5% mutated and 16% amplified cases). Moreover, EGFR, PTEN and HRAS were identified in a smaller number of carcinomas [14-18]. Importantly, NGS based studies reported additional, recurrent alterations in the mutational landscape of HNSCC and delivered new information on the frequency of particular mutations as summarized below.

Table 1. Analysis of mutated genes publicly available HNSCC NGS data identifies commonly altered oncogenes and tumor suppressors.

Single nucleotide variant (SNV) data was downloaded from all publicly available NGS data sets using the Oncomine database (n = 462). Genes that were mutated in >4% of all samples are shown in the table with the respective mutation rate. Table headings are described following italics: Mutation Frequency: percentage of tumors with SNVs for the gene listed. Oncomine Functional Classification: SNVs were then classified as “gain” or “loss” of function based on both the presence of “deleterious” mutations (e.g. those that insert stop codons or frameshifts) as well as the presence of corresponding gene amplifications or deletions in the HNSCC data sets. Deleterious Frequency in Mutated Samples: Of the samples identified with mutations, the percentage of mutations predicted to cause frameshifts or stop codons was calculated.

| Gene Symbol |

Mutation Frequency |

Oncomine Functional Classification |

Deleterious Frequency in Mutated Samples |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 | 67.5% | Loss | 34.6% |

| FAT1 | 21.6% | Loss | 81.0% |

| NOTCH1 | 17.5% | Loss | 37.0% |

| CDKN2A | 16.7% | Loss | 28.6% |

| PIK3CA | 16.5% | Gain | 0.0% |

| KMT2D | 14.7% | Loss | 57.4% |

| CASP8 | 11.0% | Loss | 43.1% |

| NSD1 | 9.3% | Loss | 60.5% |

| EP300 | 6.7% | Gain | 12.9% |

| FAT2 | 6.5% | Loss | 30.0% |

| DST | 6.3% | Loss | 31.0% |

| NOTCH2 | 5.0% | Loss | 56.5% |

| HRAS | 5.0% | Gain | 0.0% |

| FBXW7 | 4.8% | Loss | 18.2% |

| NFE2L2 | 4.8% | Gain | 0.0% |

| MUC4 | 4.3% | Gain | 5.0% |

| AJUBA | 4.1% | Loss | 73.7% |

| EPHA2 | 4.1% | Loss | 63.2% |

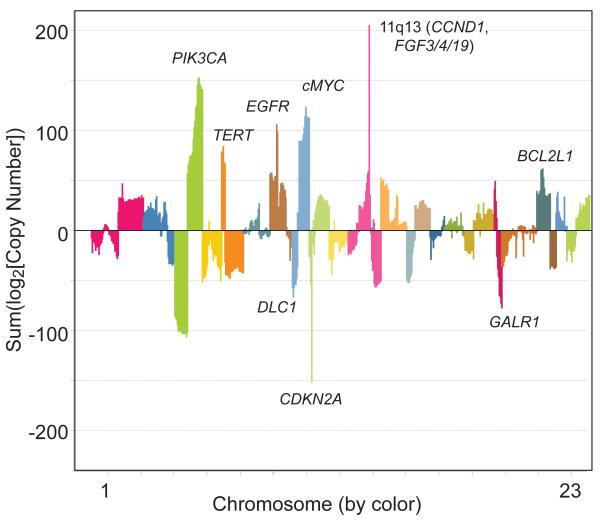

Figure 1. Meta-analysis of copy number alterations in publicly available aCGH and NGS HNSCC datasets.

Copy number data from aCGH or NGS data sets from Stransky [17], Peng [79], Agrawal [14] and the HNSCC TCGA [15] data (n = 500) sets were pooled for a meta-analysis of copy number alterations in HNSCC. For each sample, the log2 value of the copy number alteration was calculated and samples were summed on a gene by gene level [e.g. to calculate the overall copy number alteration across these data sets, the following summation was performed: log2(Copy number EGFR_sample1) + log2(Copy number EGFR_sample2)…etc. + log2(Copy number EGFR_sample500)]. Thus, the most recurrently altered genes with high level amplifications or deletions from all genetic subsets of HNSCC are highlighted in the plot. Representative and established HNSCC oncogenes and tumor suppressors are listed next to respective chromosome alterations.

NOTCH gene family

NGS analyses identified the NOTCH1 gene as the third most commonly mutated gene in HNSCC. In the above mentioned publications [14-17], NOTCH1 mutations were observed in 8-15% of samples in addition to less frequent mutations of the NOTCH2 (5% of samples) and NOTCH3 (4% samples) genes. Also copy number alterations resulting in deregulation of the NOTCH pathway genes were observed in HNSCC. Sun W. et al. reported gain of copy number and overexpression of the NOTCH ligands JAG1 and JAG2 and the receptor NOTCH3[19]. Interestingly, mutations identified in the NOTCH genes are mutually exclusive and therefore, the overall percentage of cases with NOTCH receptor mutations is probably around 20%, while genes involved in NOTCH signaling, including effectors like MAML1, are lost in an even larger subset. In addition, HNSCC is characterized by recurrent mutations in the TP63, IRF6 or MED1 genes, functionally related with NOTCH in squamous differentiation [17].

Originally described in Drosophila, NOTCH family members are transmembrane proteins that are involved in cell to cell communication and regulate squamous differentiation. Activating NOTCH mutations were already described in lymphocytic leukemias and lymphomas and were also recently found in oral squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese population [20-22], but are only reported in rare cases of HNSCC in Caucasian population [19]. In contrast, most cases of HNSCC harbor loss-of-function NOTCH receptor mutations targeting the transactivating C-terminal ankyrin repeat domain, the extracellular ligand binding domain and splice junctions were found [14, 17]. These inactivating mutations resemble therefore mutations recently described for chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) [23] and suggest a context dependent nature of NOTCH alterations in HNSCC.

In fact, in transgenic mouse models of NOTCH signaling deficient epidermal basal cells (Keratin 5 expressing), barrier deficient squamous layers form pre-neoplastic lesions, which can be driven to malignant transformation by secretion of WNT ligands from infiltrating immune cells [24, 25]. In some cases, tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T-cells are recruited to these pre-neoplastic lesions to gradually clear NOTCH deficient cells from the area. However, when CD11+Gr1+ myeloid cells are recruited to the lesion, they secrete WNT ligands to augment β-catenin signaling and promote tumor growth as well as a pro-malignant niche in adjacent epidermal cells. Thus, WNT signaling is critical for the growth of NOTCH-deficient squamous cell carcinomas in these models.

Recently, the PORCN (porcupine) inhibitor WNT974 (formerly known as LGK974) was developed for the treatment of NOTCH-deficient HNSCC. Porcupine is a membrane bound O-acyltransferase that is dedicated to WNT post-translational acylation (palmitoylation), which is required for WNT secretion [26]. Consequently, WNT974 is postulated to block the accumulation of extracellular WNT ligands by both tumor cell autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms, suggesting its effective use for targeting NOTCH deficient tumors of epidermal lineage. It was demonstrated that WNT974 effectively blocks WNT ligand-dependent β-catenin-mediated transcription of several target genes including AXIN2 (canonical WNT signaling) [27]. Importantly, an unbiased analysis of pharmacodynamic response in combination with whole exome sequencing of HNSCC models identified disruptive NOTCH1 mutations as a critical biomarker of WNT974 pharmacodynamic response. Taken together, NGS based studies demonstrated that disruption of squamous cell differentiation is one of the fundamental mechanisms in HNSCC and it has been demonstrated that targeted inhibition of WNT signaling may be a viable therapeutic strategy for these tumors.

Apoptosis related genes

Stransky et al. reported recurrent mutations of the TP53 gene (62% of cases) and the apoptosis initiator - CASP8 gene (8% of cases) to be among the most frequent in head and neck cancer [17]. This finding is in line with the general observation for human cancers where loss-of-function alterations are frequently identified in apoptosis related genes. Deregulation of apoptosis results in growth advantage of the mutated cells and, what is clinically important, is also involved in chemoresistance of the malignant cells [28]. Remarkably, in the latest NGS paper of the TCGA consortium it was shown that CASP8 and HRAS mutations are enriched in a subpopulation of tumors that are characterized by very infrequent copy number alterations (CNAs), also indicated as CNA-quiet. Next to the separate HPV+ subgroup (see also below), this HPV− CNA-quiet subgroup was characterized by a favorable prognosis and forms a genetically third subgroup of tumors. This same subgroup was described in a previous study using BAC arrays [29].

Other tumor suppressor genes

Several tumor suppressor genes not implicated in HNSCC before have been identified by NGS studies to carry inactivating mutations in this tumor. Mutations in the FBXW7 gene for example, reported by Agrawal et al. are predicted to inhibit the tumor suppressor activity of this protein by blocking its ability to target oncoproteins like MYC for degradation [14, 30]. Interestingly, as one of the FBXW7 protein targets is also NOTCH, it was speculated that the observed mutations in FBXW7 might also modulate the squamous cell differentiation through the interaction with NOTCH [31]. This tempting hypothesis requires however further verification, not in the least as inactivating mutations in FBXW7 cause activation of NOTCH1, which does not fit with the role of NOTCH1 as tumor suppressor gene in HNSCC

Besides, mutations in the FAT1 gene in 12-30% of HNSCC tumor samples have been reported [14, 15, 17, 32]. This gene belongs to the cadherin family, which is frequently altered in cancer, and was first described as a controller of cell proliferation and polarity in Drosophila [33, 34]. RNAi knockdown experiments demonstrated that FAT1 loss results in altered cell to cell contact and disturbed polarity of the cells, both typical characteristics of tumors [34]. In line with this, the majority of the alterations identified by the Cancer Genome Atlas Network include deletions and truncating mutations that result in a dysfunctional protein that suggests a tumor suppressor functionality of FAT1 in HNSCC. Interestingly, according to the presented data, HNSCC shows the highest FAT1 mutation rate among human neoplasms.

NGS also identified other genes frequently mutated (15% of cases) in laryngeal carcinomas: CTNNA2 and CTNNA3, encoding α-catenins [35]. Functional studies demonstrated an increase in the migration and invasive ability of HNSCC cells producing mutated forms of CTNNA2 and CTNNA3 or in cells where both α-catenins are silenced. Analysis of the clinical relevance of these mutations demonstrates that they are associated with poor prognosis. The authors conclude that CTNNA2 and CTNNA3 are tumor suppressor genes.

Genetic Biomarkers

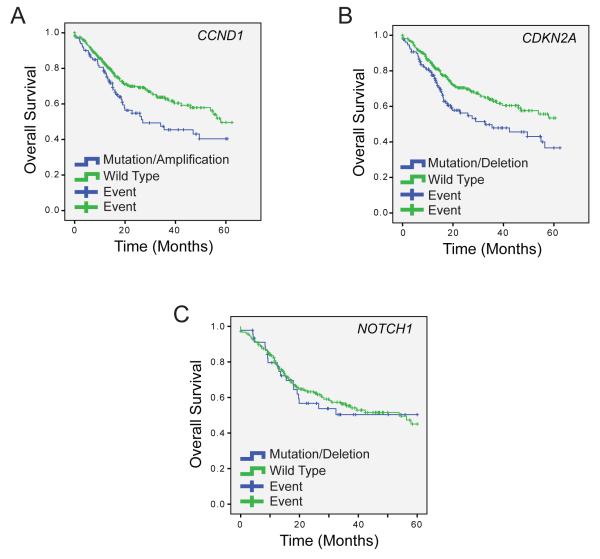

Historically, immunohistochemistry-based assays to determine protein expression have been used to develop biomarkers for disease outcomes and response to clinical intervention. With the quantity of NGS data available from the TCGA and accompanying studies, we can now begin to characterize genetic biomarkers of disease outcomes for the specific tumors represented in these cohorts. Importantly, previous studies have associated PIK3CA mutations, EGFR copy number amplifications, and TP53 mutations with worse survival in HNSCC [36-39]. However, there is a lack of further significant analysis into additional genetic mutational predictors of survival or clinical phenotypes, especially with recently described genomic aberrations, and some existing data conflicts over whether specific disruptive genetic events correlate with survival. For example, while some studies have demonstrated significantly worse prognosis with PIK3CA mutations, this correlation is not statistically significant in the most recent HNSCC TCGA data set (p = 0.292 on log rank). CCND1 and CDKN2A alterations, however, independetly correlate with overall survival of stage III/IV cancers in the TCGA cohort, (p = 0.03 and 0.01, respectively, on log rank; Figure 2A and B). However, some alterations that appear critical for pathogenesis of disease subsets like NOTCH1 mutations do not correlate with survival of patients with stage III/IV cancers (p = 0.86 on log rank, Figure 2C). In the future, as we gain a better understanding of the relationships between commonly altered genes in pathways (e.g. the NOTCH pathway), or by analyzing events across multiple pathways, this type of analysis may shed more insight into the genetic signatures that associate with clinical outcomes, and ultimately lead to a significant utility in NGS analysis at diagnosis.

Figure 2. Survival based on DNA alteration status from HNSCC TCGA data.

5-year overall survival from stage III and IV HNSCC TCGA patients with copy number variation data on 386 cases and mutation data on 232 cases. HPV positive patients were included in the analysis. CCND1 alterations (copy number amplification and mutation) (A) and CDKN2A alterations (copy number loss and mutation) (B) correlate with overall survival, but NOTCH1 aberrations (C) do not predict outcome. Log rank p values for each aberration are shown in the text.

NGS identifies distinct genetic alterations in HPV(+) and HPV(−) HNSCCs

NGS is a convenient technique to identify HPV(+) subclones in the tumor samples by mapping of reads to databases of viral genomes. The overall frequency of HPV infected HNSCCs reported in NGS based studies varies between 19-33% and is strictly dependent on the localization of the tumor with oropharyngeal tumors being most frequently infected [15, 40]. The Cancer Genome Atlas Network reports that HPV(+) oropharyngeal tumors accounts for 64% of tumors in this localization [21].

In line with earlier reports, NGS-based studies showed significant differences in the mutational profiles of HPV(+) and HPV(−) HNSCCs. HPV(+) tumors are characteristic for lower overall number of mutations as compared to HPV(−) tumors [29]. This was confirmed in both the Stransky et al. [17] and Agrawal et al. [14] studies, which reported lower mutation rates of HPV(+) tumors compared to negative. The highest difference is observed in TP53 mutations that are detected in almost all HPV(−) cases whereas found only sporadically in HPV(+) cases [41, 42]. The same is true for the frequent CDKN2A homozygous deletions,cyclin D1 overexpression and NOTCH1 mutations that are identified primarily in HPV(−) specimens [43]. This observation must be explained in light of HPV driven carcinogenesis where the viral E6 oncoprotein tags cellular p53 protein for degradation and the E7 protein abrogates the function of the pRb proteins leading to a bypass of the G1/S restriction point of the infected cell [44]. Due to this mechanism, disruptive genomic events deregulating the activity or expression of these proteins are infrequent HPV(+) tumors. Therefore, it has been postulated that HNSCC tumors caused by chemical agents are molecularly distinct from those caused by HPV with respect to genetic changes, expression profiles, microRNA expression profiles and protein expression profiles.

Nevertheless, NGS studies identified gain of function PIK3CA mutations predominantly in HPV(+) tumors [36]. These proliferation promoting mutations are observed mainly in three hotspots (E542K, E545K, H1047R/L) as indicated in the cBioPortal [16, 45]. PIK3CA encodes the kinase catalytic subunit p110α that acts in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway that is altered with a high frequency in HNSCC [46]. There have been speculations on the biological meaning of the co-occurring HPV infections and PIK3CA mutations. Recently, Henderson et al. proposed a model in which antiviral APOBEC enzymes are the main source in PIK3CA mutations in cancers including HNSCCs [47]. APOBEC enzymes of known antiviral properties catalyze the deamination of cytosine bases in nucleic acids – a mechanism that alters the sequence of DNA or RNA and is a protective mechanism aimed at the inactivation of the viral genomes [48]. However, it has been demonstrated that APOBEC enzymes can also act as mutators and target cancer related genes like TP53 in the host cell genome [49]. Therefore, HPV infection may be responsible for the elevated APOBEC activity in HNSCC leading to frequent APOBEC mediated mutations including these of PIK3CA, or alternatively, HPV(+) tumors that show lower overall frequency of mutations as compared to HPV(−) tumors, may display positive selection for APOBEC mediated mutations [48].

NGS and personalized cancer treatment

The above discussed observation of distinct molecular profiles in patients with HPV(+) versus HPV(−) tumors has major consequences for prognosis. Most HPV(+) tumors have a very favorable prognosis despite the fact that most patients present with advanced stage of disease. This observation that is widely documented, has initiated clinical trials to adjust treatment decisions, thereby being the first step towards personalized treatment in HNSCC by molecular characteristics instead of site, stage of disease or histological factors. Recently, the first free internet tool that uses various NGS data (genome, exome transcriptome) that allows the detection and annotation of HPV genome became available and can further improve treatment decisions [50]. Moreover, proper assessment of alterations of the PI3 kinase (PI3K) pathway that are particularly prevalent in HPV(+) tumors may aid in the interpretation of current clinical trials of PI3K, AKT, and mTOR inhibitors in HNSCC [36] and enhance outcomes for new patients.

In fact, many multidisciplinary tumor boards are beginning to use NGS information to enhance treatment recommendations from the onset of clinical intervention by investigating patient options with ongoing clinical trials and experimental therapies. Even though most current personalized medicine tumor boards (PMTBs) focus on advanced or non-resectable disease from multiple tumor sites, one of these studies has already demonstrated a 7% improvement in objective response rate with patient-matched as compared to non-matched targeted therapy [51]. Integrating the experiences learned from these multi-site tumor boards such as the MiONCOseq trial (NCT01576172), which is open to advanced, metastatic tumors of from all tissue sites, with Head and Neck-specific experiences will be critical in achieving further improvements to overall patient survival. This is critical, for example, when considering experiences with the use of anti-HER2 therapies in tumors from different sites. Despite the success of these therapies in HER2-amplified and overexpressed breast cancer, trastuzumab did not show survival benefit in HER2-amplified and overexpressed ovarian cancers [52]. Consequently, the evaluation of therapeutic efficacy of targeted therapies needs to be carefully considered from both a multi-tumor site perspective as well as from HNSCC specific experiences. The quality and depth of clinical testing [53, 54] and ethical standards [5] surrounding these personalized clinical trials have been discussed.

In a similar manner to how interdisciplinary tumor boards utilize DNA sequencing information, the integration of NGS into clinical decision making also enables the evaluation of RNA-expression levels and simplifies gene fusion calling. Although recurrent gene fusions are rare in HNSCC, FGFR2 and FGFR3 gene fusions occur in 1-3% of HNSCCs and these tumors may be sensitive to FGFR inhibitors [55]. From a bioinformatics perspective, the identification of gene fusions is much easier from RNA-level analysis. In contrast to established genetic lesions, there are relatively few examples of established expression-based companion diagnostics. Notably, Herceptin is used in HER2 amplified, and over-expressed breast cancers and PD-L1 inhibitors are being evaluated in advanced melanoma for PD-L1 overexpressing tumors [56, 57]. PD-L1 is not commonly amplified in these tumors and alternative mechanisms drive overexpression of RNA and protein levels, which are related to the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [58, 59]. Consequently, RNA-sequencing and expression analysis of pivotal genes such as HER2, PD1 and PD-L1 combined with genomic sequencing will be critical as the field advances and will need to be independently assessed for their utility as potential companion diagnostics.

Another promising field for direct application of NGS in clinical practice is the detection of tumor specific mutations in patients’ blood, called “liquid biopsy”. This diagnostic procedure is based on sequencing DNA fragments circulating in the blood (circulating tumor DNA: ctDNA) that derive from apoptotic or necrotic tumor cells. It is expected that ctDNA mutation patterns may eventually predict response to treatment and guide therapeutic choices [60]. Recent studies suggest that ctDNA might be representative of the tumor genome and help in identifying tumor clones without the need of invasive tumor biopsies [61-63]. The advantage of NGS lies in its’ potential to detect mutations in ctDNA from single tumors cells and therefore is an interesting candidate tool to detect relapsing, second primary or metastatic tumors. Currently, with the aim to find diagnostic biomarkers, much effort is put worldwide in investigating different aspects of ctDNA including the identification of tumor specific mutations, methylation level or copy number alterations. In future, interpretation of this information for clinical intervention by multidisciplinary tumor boards will be critical to enhance the clinical utility of next generation sequencing techniques.

Tumor heterogeneity: an evolving problem for Personalized Medicine

High genetic instability observed in the genomes of malignant cells is a hallmark of cancer. An accumulation of genetic alterations drive the clonal evolution of tumor cells. Moreover, most mutations are not driving the tumor, but are in fact passengers that occurred by chance, but that may become very important when tumors are treated. The resulting heterogenic cell clones undergo selection that leads to the development of aggressive clones showing growth advantage over the surrounding cells [64]. This phenomenon was characterized by Peter Nowell in 1976 in the attempt to explain the increasing aggressiveness of tumors in time [65]. The same mechanism is also responsible for chemo- and radioresistance in case of which selection unveils cell clones resistant to specific therapeutics. It has been recently demonstrated, that high intratumoral genetic heterogeneity is associated with tumor progression, adverse treatment outcomes and a shorter overall survival in HNSCC [66]. In this work the authors used WGS data from the 74 cases of HNSCC cases previously used by Stransky et al. [17], and for each tumor they calculated mutant-allele tumor heterogeneity (MATH), which is a quantitative measure of tumor heterogeneity based on mutation rates from exome data and has been proposed a putative biomarker for stratifying outcomes of high-risk features [67, 68]. MATH was not related to overall mutation rate, but was higher in HNSCC with disruptive TP53 mutations and in HPV-negative cases. Furthermore, each additional unit of increase in MATH was associated with 4.7% increased hazard of death, and higher MATH was found to be strongly associated with shorter overall survival [66].

Complete profiles of mutated genes through which HNSCC cells acquire chemo- or radioresistance are not known yet. Nevertheless, overexpression of FOXC2, MDR1, MRP2, ERCC1, PDGF-C, NRG1, survivin and other genes in chemoresistant HNSCC cells has been reported recently [69-71]. Moreover, Li and colleagues demonstrated that miRNA expression profiles, assessed with NGS are found to be related to radio-resistance of nasopharyngeal carcinoma [72]. They found three candidate miRNAs (miR-371a-5p, miR-34c-5p, miR-1323) that were overexpressed and three candidate miRNAs (miR-324-3p, miR-93-3p, miR-4501) that were down-regulated in radio-resistant nasopharyngeal cancer cells. Thus, in some cases, NGS may be able to identify multidrug resistant tumors that may benefit from alternative interventions.

Another advantage of NGS lies in its potential to detect therapy significant mutations in minor cell clones that would otherwise be missed due to their low cell count, which can be overcome by high read depths. NGS might overcome this problem by identifying therapy significant cells (mutations) in a heterogenous probe [73]. Therefore, NGS can potentially facilitate the development of treatment that specifically targets single resistant cells or these with metastatic potential. Alternatively, active biopsy of accessible tumors (and possibly analysis of cfDNA) and sequencing during the course of targeted therapy may enable personalized medicine tumor boards to identify emerging populations of resistant clones and alter the course the therapy in a clinically meaningful timeframe. Likewise, such information will be critical for the development of combination therapies to counteract the compensatory resistance mechanisms that rescue tumor cells from patient-matched targeted monotherapies.

Personalized Medicine: Patient Stratification

As NGS is integrated into tumor boards and the clinical decision making process, an important question is how to select therapies for a patient with a genetically complex tumor? In some cases, such as epidemiologically low risk tumors that have relatively few disruptive genomic events the selection of therapy may be fairly obvious, but most often HNSCCs have complex genomes with many different mutations regardless of associated risk-factors [32]. Thus, in addition to accounting for spatial genetic heterogeneity within the tumor, PMTBs will also have to account for multiple driver mutations in individual components of the tumors (e.g. a NOTCH1/PIK3CA double mutant). In this case, should the patient receive a WNT pathway inhibitor, PIK3CA inhibitor or both in combination? As it stands, there is no accepted or established mutation or other genomic signature that influences the routine guideline-based treatment of HNSCC and PTMBs will have to carefully annotate the response of patients to targeted therapies with genomics data to begin to build an understanding of individual responses for the most common genetic subsets of disease. In fact, the FDA has only approved 19 companion diagnostic tests for use in the treatment of cancer, some of which are based on protein level expression [74]. While cetuximab, an EGFR antibody-based therapy, is already being incorporated into standard management of HNSCCs [75, 76], many other targeted treatments such as the PIK3CA inhibitor, BYL719, remain investigational in early stage clinical trials [77, 78]. It is estimated that in the next decades, precise genetic profiling of mutation in tumors as well as a wide range of targeted anti-tumor drugs will become available. Thus, careful studies of both response to monotherapies as well as addressing how to effectively combine therapies in tumors with complex mutational loads are needed to fully understand how leverage genomics to improve overall patient survival.

In conclusion, NGS brought new insight into the biology of HNSCC and revealed its’ high genetic complexity. For today, the interplay among the identified alterations and their meaning in the context of tumor development and treatment are largely unknown. Therefore, it will be a challenge of the next years to interpret the already available sequencing data, perform prospective clinical trials and deliver the results in a clinically applicable form.

Key Message.

The emergence of ”personalized medicine” multidisciplinary tumor boards is becoming a reality in cancer treatment that may radically alter the standard course of clinical intervention. Thus, as we enter the genomics age and begin to integrate complex genetics data with clinical decision making, head and neck providers should be aware of the benefits, pitfalls, and future insights into personalized therapy that next generation sequencing offers.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Dr. M. Giefing received funding from the Polish National Science Centre grant 2012/05/B/NZ2/00870. Dr. M. Wierzbicka received funding from The National Centre for Research and Development grant INNOMED/I/7/NCBR/2014. Dr. J. Chad Brenner received funding from NIH Grants T32 DC005356 and U01DE025184. Dr. Ruud H. Brakenhoff from the Dutch Cancer Society/Alpe d’HuZes, the VUmc Cancer Centrum Amsterdam foundation, and the European Commission.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Brenner has previously collaborated with Novartis on the development of WNT974 for NOTCH-deficient HNSCC.

“This article was written by members and invitees of the International Head and Neck Scientific Group (www.IHNSG.com)”.

References

- 1.Kallioniemi OP, Kallioniemi A, Sudar D, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization: a rapid new method for detecting and mapping DNA amplification in tumors. Semin Cancer Biol. 1993;4:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fertig EJ, Slebos R, Chung CH. Application of genomic and proteomic technologies in biomarker discovery. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2012:377–382. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielander I, Bug S, Richter J, et al. Combining array-based approaches for the identification of candidate tumor suppressor loci in mature lymphoid neoplasms. APMIS. 2007;115:1107–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_883.xml.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabatabaeifar S, Kruse TA, Thomassen M, et al. Use of next generation sequencing in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: a review. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkeland AC, Uhlmann WR, Brenner JC, Shuman AG. Getting personal: Head and neck cancer management in the era of genomic medicine. Head Neck. 2015 doi: 10.1002/hed.24132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sethi N, MacLennan K, Wood HM, Rabbitts P. Past and future impact of next-generation sequencing in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2015 doi: 10.1002/hed.24085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Califano J, van der Riet P, Westra W, et al. Genetic progression model for head and neck cancer: implications for field cancerization. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2488–2492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braakhuis BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter's concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727–1730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pleasance ED, Stephens PJ, O'Meara S, et al. A small-cell lung cancer genome with complex signatures of tobacco exposure. Nature. 2010;463:184–190. doi: 10.1038/nature08629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwaederle M, Elkin SK, Tomson BN, et al. Squamousness: Next-generation sequencing reveals shared molecular features across squamous tumor types. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:2355–2361. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1053669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Govindan R, Ding L, Griffith M, et al. Genomic landscape of non-small cell lung cancer in smokers and never-smokers. Cell. 2012;150:1121–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhodes DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Mahavisno V, et al. Oncomine 3.0: genes, pathways, and networks in a collection of 18,000 cancer gene expression profiles. Neoplasia. 2007;9:166–180. doi: 10.1593/neo.07112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, et al. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333:1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cancer Genome Atlas N Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517:576–582. doi: 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun W, Gaykalova DA, Ochs MF, et al. Activation of the NOTCH pathway in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1091–1104. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SY, Kumano K, Nakazaki K, et al. Gain-of-function mutations and copy number increases of Notch2 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:920–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01130.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izumchenko E, Sun K, Jones S, et al. Notch1 mutations are drivers of oral tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:277–286. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klinakis A, Lobry C, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. A novel tumour-suppressor function for the Notch pathway in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;473:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature09999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demehri S, Turkoz A, Manivasagam S, et al. Elevated epidermal thymic stromal lymphopoietin levels establish an antitumor environment in the skin. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:494–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Piazza M, Nowell CS, Koch U, et al. Loss of cutaneous TSLP-dependent immune responses skews the balance of inflammation from tumor protective to tumor promoting. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:479–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Pan S, Hsieh MH, et al. Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20224–20229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaneda Y, Shimamoto H, Matsumura K, et al. Role of caspase 8 as a determinant in chemosensitivity of p53-mutated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. J Med Dent Sci. 2006;53:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smeets SJ, Brakenhoff RH, Ylstra B, et al. Genetic classification of oral and oropharyngeal carcinomas identifies subgroups with a different prognosis. Cell Oncol. 2009;31:291–300. doi: 10.3233/CLO-2009-0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldus CD, Thibaut J, Goekbuget N, et al. Prognostic implications of NOTCH1 and FBXW7 mutations in adult acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2009;94:1383–1390. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.005272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loyo M, Li RJ, Bettegowda C, et al. Lessons learned from next-generation sequencing in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2013;35:454–463. doi: 10.1002/hed.23100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickering CR, Zhang J, Neskey DM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral tongue in young non-smokers is genomically similar to tumors in older smokers. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3842–3848. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bryant PJ, Huettner B, Held LI, Jr., et al. Mutations at the fat locus interfere with cell proliferation control and epithelial morphogenesis in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1988;129:541–554. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanoue T, Takeichi M. Mammalian Fat1 cadherin regulates actin dynamics and cell-cell contact. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:517–528. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fanjul-Fernandez M, Quesada V, Cabanillas R, et al. Cell-cell adhesion genes CTNNA2 and CTNNA3 are tumour suppressors frequently mutated in laryngeal carcinomas. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2531. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lui VW, Hedberg ML, Li H, et al. Frequent mutation of the PI3K pathway in head and neck cancer defines predictive biomarkers. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:761–769. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seiwert TY, Zuo Z, Keck MK, et al. Integrative and comparative genomic analysis of HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:632–641. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Temam S, Kawaguchi H, El-Naggar AK, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor copy number alterations correlate with poor clinical outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2164–2170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poeta ML, Manola J, Goldwasser MA, et al. TP53 mutations and survival in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2552–2561. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung CH, Guthrie VB, Masica DL, et al. Genomic alterations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma determined by cancer gene-targeted sequencing. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1216–1223. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lechner M, Frampton GM, Fenton T, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma identifies novel genetic alterations in HPV+ and HPV− tumors. Genome Med. 2013;5:49. doi: 10.1186/gm453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nichols AC, Chan-Seng-Yue M, Yoo J, et al. A Pilot Study Comparing HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas by Whole Exome Sequencing. ISRN Oncol. 2012;2012:809370. doi: 10.5402/2012/809370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rettig EM, Chung CH, Bishop JA, et al. Cleaved NOTCH1 Expression Pattern in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Is Associated with NOTCH1 Mutation, HPV Status, and High-Risk Features. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8:287–295. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.zur Hausen H. Papillomavirus infections--a major cause of human cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1288:F55–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. 2013;6:l1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rizzo G, Black M, Mymryk JS, et al. Defining the genomic landscape of head and neck cancers through next-generation sequencing. Oral Dis. 2015;21:e11–24. doi: 10.1111/odi.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henderson S, Chakravarthy A, Su X, et al. APOBEC-mediated cytosine deamination links PIK3CA helical domain mutations to human papillomavirus-driven tumor development. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1833–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Conticello SG. The AID/APOBEC family of nucleic acid mutators. Genome Biol. 2008;9:229. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burns MB, Temiz NA, Harris RS. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandrani P, Kulkarni V, Iyer P, et al. NGS-based approach to determine the presence of HPV and their sites of integration in human cancer genome. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1958–1965. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsimberidou AM, Wen S, Hong DS, et al. Personalized medicine for patients with advanced cancer in the phase I program at MD Anderson: validation and landmark analyses. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4827–4836. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bookman MA, Darcy KM, Clarke-Pearson D, et al. Evaluation of monoclonal humanized anti-HER2 antibody, trastuzumab, in patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma with overexpression of HER2: a phase II trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:283–290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aziz N, Zhao Q, Bry L, et al. College of American Pathologists' laboratory standards for next-generation sequencing clinical tests. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:481–493. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2014-0250-CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simen BB, Yin L, Goswami CP, et al. Validation of a next-generation-sequencing cancer panel for use in the clinical laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:508–517. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0710-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu YM, Su F, Kalyana-Sundaram S, et al. Identification of targetable FGFR gene fusions in diverse cancers. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:636–647. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang X, Zhou J, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. The activation of MAPK in melanoma cells resistant to BRAF inhibition promotes PD-L1 expression that is reversible by MEK and PI3K inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:598–609. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frederick DT, Piris A, Cogdill AP, et al. BRAF inhibition is associated with enhanced melanoma antigen expression and a more favorable tumor microenvironment in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1225–1231. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marzese DM, Hirose H, Hoon DS. Diagnostic and prognostic value of circulating tumor-related DNA in cancer patients. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2013;13:827–844. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2013.845088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lianos GD, Mangano A, Cho WC, et al. Circulating tumor DNA: new horizons for improving cancer treatment. Future Oncol. 2015;11:545–548. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murtaza M, Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, et al. Non-invasive analysis of acquired resistance to cancer therapy by sequencing of plasma DNA. Nature. 2013;497:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakai K, Horiike A, Irwin DL, et al. Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor T790M mutation in plasma DNA from patients refractory to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:1198–1204. doi: 10.1111/cas.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Swanton C. Intratumor heterogeneity: evolution through space and time. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4875–4882. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.959840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mroz EA, Tward AD, Pickering CR, et al. High intratumor genetic heterogeneity is related to worse outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119:3034–3042. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rocco JW. Mutant allele tumor heterogeneity (MATH) and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12105-015-0617-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mroz EA, Tward AD, Hammon RJ, et al. Intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity and mortality in head and neck cancer: analysis of data from the Cancer Genome Atlas. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Govindan SV, Kulsum S, Pandian RS, et al. Establishment and characterization of triple drug resistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:3025–3032. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamano Y, Uzawa K, Saito K, et al. Identification of cisplatin-resistance related genes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:437–449. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou Z, Zhang L, Xie B, et al. FOXC2 promotes chemoresistance in nasopharyngeal carcinomas via induction of epithelial mesenchymal transition. Cancer Lett. 2015;363:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li G, Qiu Y, Su Z, et al. Genome-wide analyses of radioresistance-associated miRNA expression profile in nasopharyngeal carcinoma using next generation deep sequencing. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang XC, Xu C, Mitchell RM, et al. Tumor evolution and intratumor heterogeneity of an oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Neoplasia. 2013;15:1371–1378. doi: 10.1593/neo.131400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rubin EH, Allen JD, Nowak JA, Bates SE. Developing precision medicine in a global world. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1419–1427. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu S, Chen P, Hu M, et al. Randomized, controlled phase II study of post-surgery radiotherapy combined with recombinant adenoviral human p53 gene therapy in treatment of oral cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013;20:375–378. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2013.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ribas A, Hodi FS, Callahan M, et al. Hepatotoxicity with combination of vemurafenib and ipilimumab. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1365–1366. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1302338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Conley BA, Doroshow JH. Molecular analysis for therapy choice: NCI MATCH. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:297–299. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Givens DJ, Karnell LH, Gupta AK, et al. Adverse events associated with concurrent chemoradiation therapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:1209–1217. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peng CH, Liao CT, Peng SC, et al. A novel molecular signature identified by systems genetics approach predicts prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]