Abstract

Studies of acetylcholine degrading enzymes acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) suggested their potential role in the development of fibrillar amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques (amyloid plaques). A recent GWAS analysis identified a novel association between genetic variations in the BCHE locus and amyloid burden. We studied BChE immunoreactivity in hippocampal tissue sections from AD and control cases, and examined its relationship with amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), dystrophic neurites (DN), and neuropil threads (NT). Compared to controls, AD cases had greater BChE immunoreactivity in hippocampal neurons and neuropil in CA2/3, but not in the CA1, CA4, and dentate gyrus. The majority of amyloid plaques (>80%, using a pan-amyloid marker X-34) contained discrete neuritic clusters which were dual-labeled with antibodies against BChE and phosphorylated tau (clone AT8). There was no association between overall regional BChE immunoreaction intensity and amyloid plaque burden. In contrast to previous reports, BChE was localized in only a fraction (~10%) of classic NFT (positive for X-34). A similar proportion of BChE-immunoreactive pyramidal cells were AT8 immunoreactive. Greater NFT and DN loads were associated with greater BChE immunoreaction intensity in CA2/3, but not in CA1, CA4, and dentate gyrus. Our results demonstrate that in AD hippocampus, BChE accumulates in neurons and plaque-associated neuritic clusters, but only in a small proportion of NFT. The association between greater neurofibrillary pathology burden and markedly increased BChE immunoreactivity, observed selectively in CA2/3 region, could reflect a novel compensatory mechanism. Since CA2/3 is generally considered more resistant to AD pathology, BChE upregulation could impact the cholinergic modulation of glutamate neurotransmission to prevent/reduce neuronal excitotoxicity in AD hippocampus.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid, butyrylcholinesterase, hippocampus, tau

Introduction

Impaired cholinergic neurotransmission contributes to cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), thus current symptomatic therapies for mild-to-moderate AD aim to block the acetylcholine (Ach) degrading enzymes, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE). The distribution and localization of AChE in normal aging and AD are well described1, 2, however less is known about BChE, despite its role as an important modulator of Ach metabolism3–6. BChE inhibition is clinically significant as it provides benefit to patients resistant to AChE-specific inhibitor therapy7. Furthermore, BChE inhibition may have additional, disease-modifying effects as it influences brain β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide concentration and ameliorates Aβ-induced cognitive impairment8. Recently, an association was reported between genetic variation in the BChE gene locus and Aβ-containing amyloid pathology burden measured using florbetapir PET imaging9. These observations warrant continued and more detailed analyses of BChE in AD. The distribution and cellular localization of BChE in the hippocampus have been described using histochemical methods in tissue sections5, 10, but results from this procedure vary across laboratories11. Furthermore, several studies, using biochemical and histochemical methods, reported increased BChE activity in AD12, 13, as well as an association between BChE histochemical reaction and major neuropathological lesions of AD, amyloid-structured aggregates of fibrillar Aβ in plaques (hereafter referred to as amyloid plaques) and phosphorylated, fibrillar tau amyloid in neurofibrillary tangles (NFT)14–16. To extend these investigations, the current postmortem immunohistochemical study used a BChE-specific antibody to analyze BChE protein localization, distribution, and immunoreaction intensity in the hippocampus from normal and AD cases, and to investigate its relation to amyloid structures of Aβ plaques and neurofibrillary pathology, targets of PET radioligands currently in use or under development as imaging biomarkers for AD17.

Methods

Cases

We examined 11 cases with clinical and neuropathological diagnoses of AD and 10 age-matched controls with no clinical history of dementia, from Choju Medical Institute, Fukushimura Hospital and Ishizaki Hospital in Japan (Table 1). Cases were free of neuropathological lesions other than AD, except one AD case (#11) with coexisting Lewy bodies in brain stem and amygdala bilaterally with no involvement of the neocortex of hippocampus, and one AD case (#15) with isolated, small infarctions bilaterally in the thalamus. Clinical diagnosis of AD was based on DSM-IV18 and NINCDS/ADRDA19 criteria. Neuropathological diagnosis was determined by a neuropathologist. All AD cases were assigned neuropathological diagnosis of “definite” AD, while controls were “not AD” according to CERAD criteria20. NFT pathology was staged according to Braak and Braak21 (Table 1). Review of medical records revealed that one subject (case #14) had received donepezil that was discontinued one year before death, but none of the subjects in the study had received rivastigmine or galantamine.

Table 1.

Case demographic details

| Case number |

Clinical diagnosis |

CDR | Age (y) |

Sex | Brain weight (g) |

PMI (hr) |

Braak stage |

CERAD stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control | 0 | 84 | M | 1060 | 3 | 0 | A |

| 2 | Control | 0 | 85 | F | 1110 | 8 | I | A |

| 3 | Control | 0 | 80 | M | 1230 | 2 | I | A |

| 4 | Control | 0 | 81 | M | 1320 | 14 | I | A |

| 5 | Control | 0 | 87 | F | 1080 | 10.5 | I | A |

| 6 | Control | 0 | 78 | F | 1280 | 3.5 | I | A |

| 7 | Control | 0 | 95 | F | 1190 | 12 | I | A |

| 8 | Control | 0 | 77 | M | 1130 | 1 | II | A |

| 9 | Control | 0 | 94 | M | 1115 | 15 | II | A |

| 10 | Control | 0 | 85 | M | 1090 | 2.5 | II | B |

| 11 | AD | 3 | 72 | M | 1160 | 4 | IV | B |

| 12 | AD | 3 | 93 | F | 890 | 3 | IV | C |

| 13 | AD | 3 | 74 | M | 1180 | 10 | IV | C |

| 14 | AD | 3 | 83 | F | 990 | 3 | V | B |

| 15 | AD | 3 | 95 | F | 970 | 2 | V | B |

| 16 | AD | 3 | 90 | F | 990 | 7 | V | C |

| 17 | AD | 3 | 94 | F | 1010 | 43 | V | C |

| 18 | AD | 3 | 79 | M | 1130 | 6 | V | C |

| 19 | AD | 3 | 68 | M | 1050 | 6 | V | C |

| 20 | AD | 3 | 78 | F | 940 | 3 | VI | C |

| 21 | AD | 3 | 69 | F | 750 | 16 | VI | C |

CDR, Clinical dementia rating; CERAD, The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; PMI, postmortem interval.

Tissue processing and histology procedures

At autopsy, brains were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for three weeks. Coronal blocks of hippocampus were dissected at the level of the lateral geniculate nucleus, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 µm, and processed for immunohistochemistry using previously published protocols22, 23 and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against BChE (Aviva Systems Biology, catalogue #ARP44208, lot #QC14544, dilution: 1:10), generated against a synthetic immunogen corresponding to N-terminal amino acids (SSLHVYDGKFLARVERVIVVSMNYRVGALGFLALPGNPEAPGNMGLFDQQ) of butyrylcholinesterase with 100% homology to human BChE (http://www.avivasysbio.com/bche-antibody-n-terminal-region-arp44208-t100.html). Immunohistochemical signal was abolished in preadsorption experiments (not shown) using synthetic human BChE (Aviva, catalogue #AAP44208). Sections from all subjects in the study were processed simultaneously. At least three sections from each case were immunolabeled with the BChE antibody, and additional three sections from each case were processed with cresyl violet to delineate the cytoarchitectural boundaries of the hippocampus as defined by Duvernoy24.

To assess the relation between BChE immunoreactivity and plaque and neurofibrillary amyloid pathology of AD, BChE-immunoreacted sections were over-stained with the pan-amyloid dye X-34, a highly fluorescent derivative of Congo red that labels β-sheet structure of Aβ fibrils in plaques as well as tau fibrils in neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), dystrophic neurites (DN), and neuropil threads (NT), as previously described25, 26. To examine the association between BChE immunoreactivity and neurofibrillary pathology specifically, we performed dual immunofluorescence using an antibody against BChE (described above, dilution 1:20) and mouse monoclonal antibody AT8 (Thermo, catalogue #MN1020, lot #00184107, dilution 1:3,000) that interacts with epitopes mapped to phosphorylated Ser202 and phosphorylated Thr205. Primary antibodies were visualized using fluorescent Alexa dyes conjugated to secondary antibodies generated against rabbit (Alexa 488 for BChE) and mouse (Alexa 594 for AT8). Immunofluorescently labeled sections were coverslipped using DAPI containing media (Vectashield Hard Set, Vector, H-1500).

Quantitative measures

BChE immunoreaction intensity. We assessed BChE immunoreaction intensity by quantifying immunoreaction product optical density, using previously published protocols23, in dentate gyrus (DG) granule cell and molecular layers, CA4 cells and neuropil, and in stratum oriens, pyramidale (pyramidal neurons and neuropil), and radiatum of CA1 and CA2/3. Images of neuropil in AD cases were obtained using systematic random sampling and therefore included areas with varying presentation of BChE-immunoreactive plaques and surrounding, unaffected neuropil. For each case, three sections were imaged and in each subfield three images were taken using an Olympus BX53 microscope, equipped with an Olympus DP72 digital camera and Olympus cellSens Standard image capture software, using a UPlanSApo 10× objective (N.A. = 0.40; Olympus). Illumination intensity was held constant throughout image acquisition. Images were assessed for grayscale intensity using public domain image analysis software (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, United States National Institute of Health). X-34 and immunofluorescence was visualized using an Olympus BX53 microscope equipped with an X-Cite series 120 Q fluorescence illuminator and DAPI, FITC, TRITC, and violet filters. Neurofibrillary and plaque amyloid pathology load. We calculated percent area of tissue occupied by X-34 labeled amyloid structure in plaques and each of three types of neurofibrillary pathology (NFT, DN, and NT) in the same hippocampal regions assessed for BChE immunoreaction intensity. Images of X-34 stained sections were processed using the ImageJ threshold tool, and different types of X-34 positive amyloid pathology were identified as described previously26. Briefly, amyloid plaques and NFT were distinguished based on their morphology (size and shape) and localization (extracellular or intracellular). DN were identified as X-34 positive dendritic swellings associated with plaques (2–3 µm diameter), while NT were X-34 positive smaller caliber (≤1 µm diameter) threads in the neuropil. Ghost tangles were identified as extracellular skeletons of advanced NFT. BChE and X-34 colocalization. To assess the degree of colocalization/codistribution of BChE immunoreactivity with X-34-labeled amyloid structure of plaques and NFT, dual X-34/BChE labeled structures were quantified in each region of the hippocampus and reported as percent of X-34 labeled amyloid plaques or NFT containing BChE immunoreactivity. BChE and AT8 colocalization. Colocalization/codistribution of BChE and AT8 immunofluorescence was assessed qualitatively in fields CA1, 2/3, and 4).

Statistical analyses

Individual values obtained for each case were combined to calculate the mean and standard error (S.E.M.) for each group. In control and AD groups, we performed pairwise comparisons of BChE immunoreactivity or X-34 labeled pathology load in each examined subfield, using the Mann Whitney U test. Correlations of BChE immunoreaction intensity and X-34-labeled plaque and neurofibrillary pathology load were made using Spearman R. All results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. and P< 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Controls were cognitively normal (CDR=0) with Braak stages 0-II and CERAD score A (except for Case 10, CERAD score B, and no plaques in the hippocampus or dentate gyrus), while AD cases were cognitively impaired (CDR=3) with Braak stages IV-VI and CERAD score B or C (Table 1). Both case groups had similar mean age and postmortem interval, but AD cases had lower mean brain weight than controls (p<0.05).

BChE immunoreactivity in control and AD hippocampus

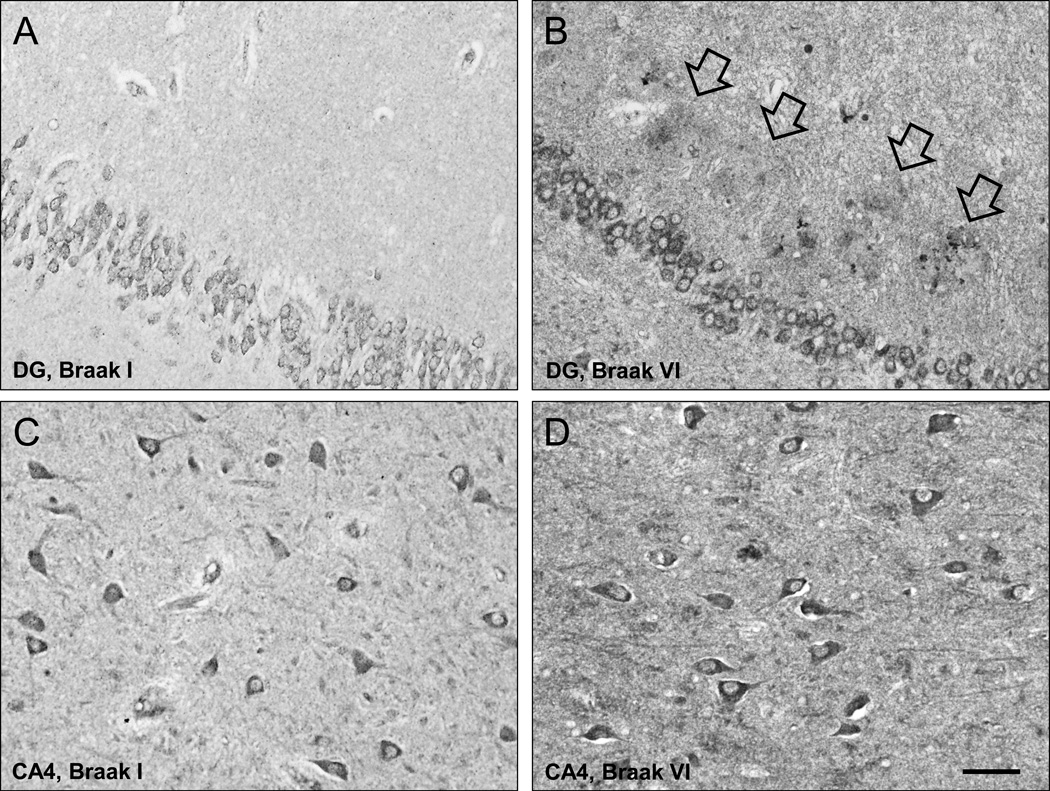

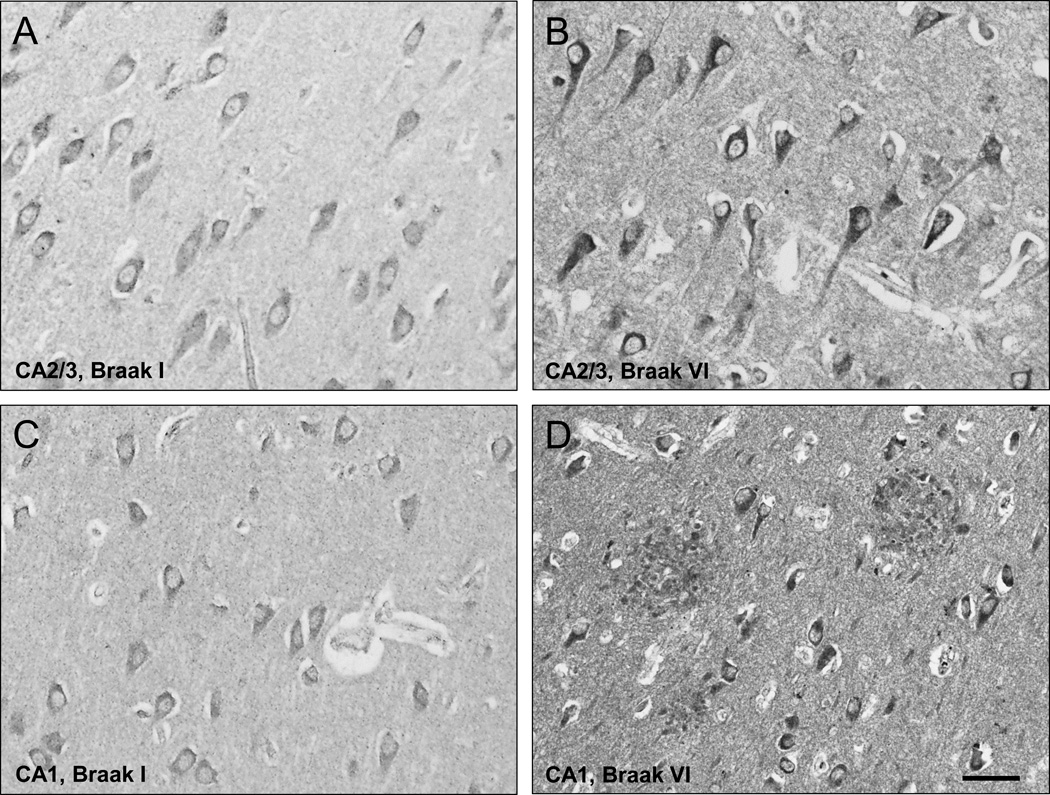

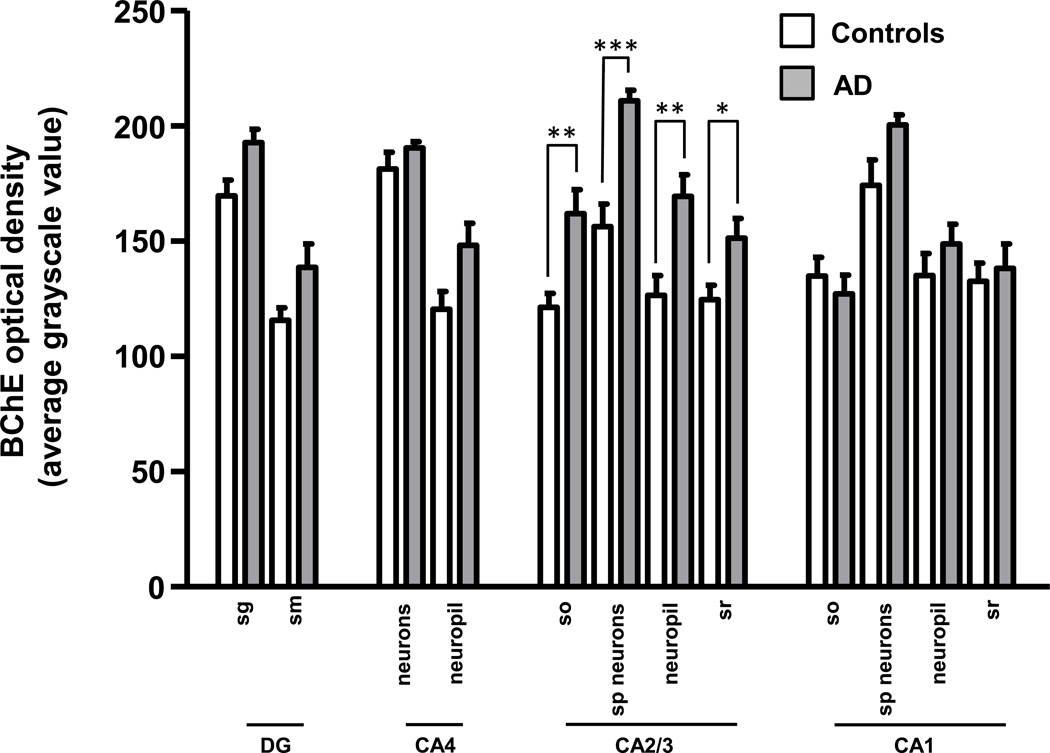

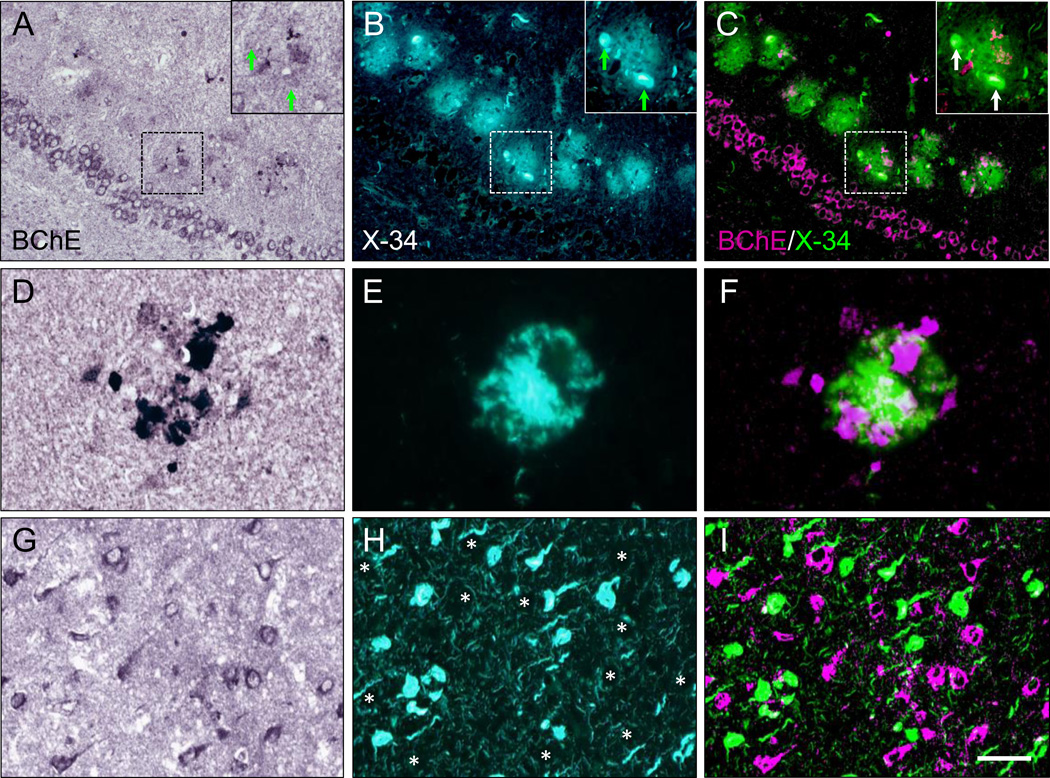

In controls, BChE immunoreactivity was prominent in neurons in the granular and polymorphic layers of dentate gyrus (DG), hilus (CA4), and pyramidal layer in CA1 and CA2/3 fields, while neuropil staining was low-to-moderate (Fig. 1A,C; 2A,C). Neuronal BChE immunoreactivity was localized to the cytoplasm in cell bodies and proximal dendritic segment, while nucleus was not labeled. We also observed BChE immunoreactivity in glial cells in the stratum oriens and in occasional BChE immunoreactive fibers traversing DG and CA4 (not shown). In AD hippocampus, the overall pattern of BChE immunoreactivity was similar to that observed in controls, however, neuronal and neuropil BChE immunoreactivity were more intense (Fig. 1B,D; 2B,D), particularly in region CA2/3 (Fig. 3, both p < 0.05). In addition to neuronal and neuropil labeling, AD cases had discrete clusters of BChE immunoreactivity in the DG molecular layer (Fig. 1B) and in CA fields (Fig. 4A–F). Quantitative analysis of dual label X-34/BChE revealed that these BChE immunoreactive clusters were localized to the majority (>80%) of X-34 labeled amyloid plaques. Plaque-associated BChE positive clusters did not co-label with X-34 (Fig. 4A–C, D–F), however, they were immunoreactive for antibody clone AT8 (Fig. 5A–C). Only a minority (~10%) of X-34-labeled NFT, primarily those in the CA1 region, contained BChE immunoreactivity (Fig. 4G–E). BChE and AT8 immunoreactivities did not colocalize in pyramidal cells (Fig 5D–F, G–I). We also observed rare extracellular ghost tangles (large NFT lacking clearly pyramidal cell shape and without visible DAPI-stained nuclei), some of them resembling tangle-associated neuritic clusters (TANC). The intensity of BChE immunoreaction product in extracellular NFT was more prominent with a more advanced fibrillar structure revealed with X-34 (Figure 6).

Figure 1.

Low-power photomicrographs of BChE immunoreactivity in the dentate gyrus (DG, A,B) and CA4 field (C,D) from representative Braak stage I control (A,C) and a Braak stage VI AD case (B,D; arrows in B point at plaque-like clusters of BChE immunoreactive neuritic elements in DG molecular layer). Scale bar = 50 µm (A,B); 100 µm (C,D).

Figure 2.

High magnification of BChE immunoreactive cells and neuropil in pyramidal cell layer of CA2/3 (A,B) and CA1 (C,D) fields from representative Braak stage I control (A,C) and a Braak stage VI AD (B,D) cases. Scale bar = 30 µm (A,B); 50 µm (C,D).

Figure 3.

Bar graph illustrating optical density measurements of BChE immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of Braak stage I–II control (empty bars) and Braak stage V–VI AD (solid bars) cases. Abbreviations: DG, dentate gyrus; SG, stratum granulosum; SM, stratum moleculare; SO, stratum oriens; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U).

Figure 4.

Dual-labeling of BChE immunoreactivity (A,D,G) and pan-amyloid X-34 fluorescence (B,E,H) in the hippocampus of a Braak stage V AD case. Clusters of BChE immunoreactive neuritic swellings (A, D) are localized to X-34-labeled plaques (B,E) in the dentate gyrus molecular layer (A–C) and CA1 region (D–F). In panels A–C, the insets show at higher magnification the dashed-outlined plaque; BChE-immunoreactive neuritic swellings do not colocalize with X-34 labeled dystrophic neurites (arrows). In panels D–F, BChE-immunoreactive clusters are co-distributed, but do not co-localize, with X-34-labeled amyloid in plaque. Panels G–I illustrate lack of colocalization of BChE with X-34 labeled neurofibrillary tangles in CA1 (asterisks in H mark positions of BChE immunoreactive cells in G). BChE and X-34 were pseudocolored and merged in (C, F, and I), with BChE colored magenta and X-34 colored green. Scale bar = 100 µm (A–C); 20 µm (D–F); 50 µm (G–I).

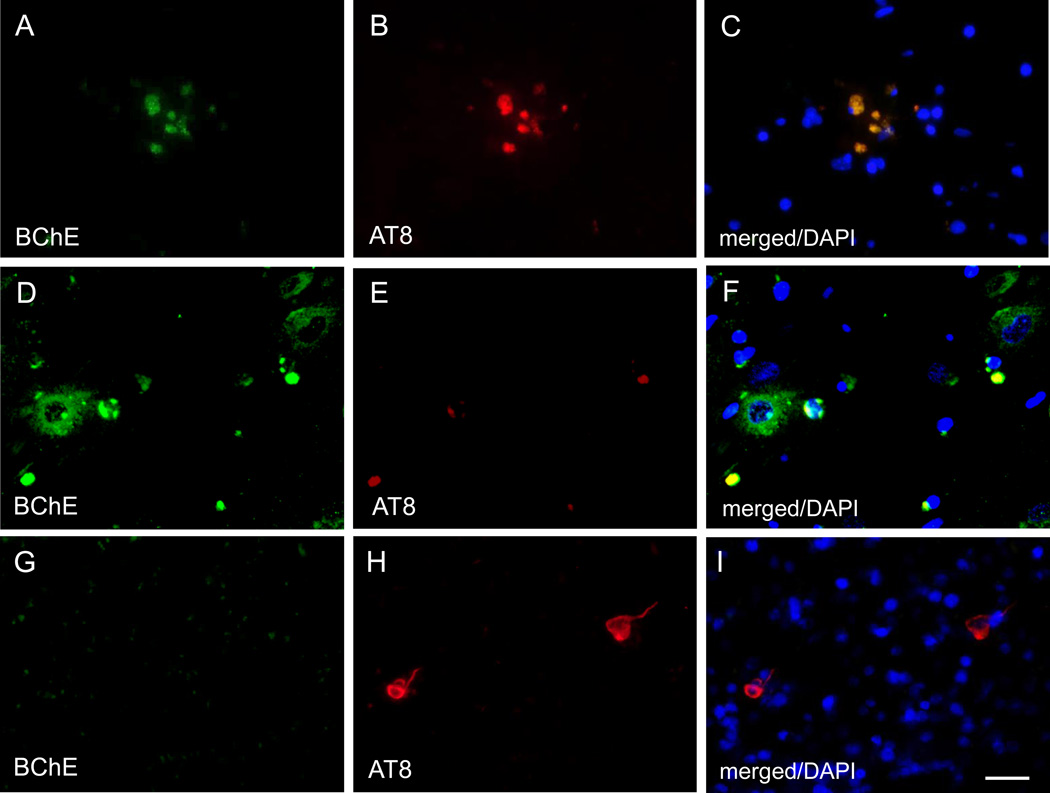

Figure 5.

Dual immunofluorescence images showing overlapping BChE and AT8 immunoreactivity in plaque-associated neuritic clusters (A–C), and no overlap between BChE and AT8 immunoreactivity in CA1 pyramidal cells (D–F and G–I). Scale bar = 25 µm (A–F), 35 µm (G–I).

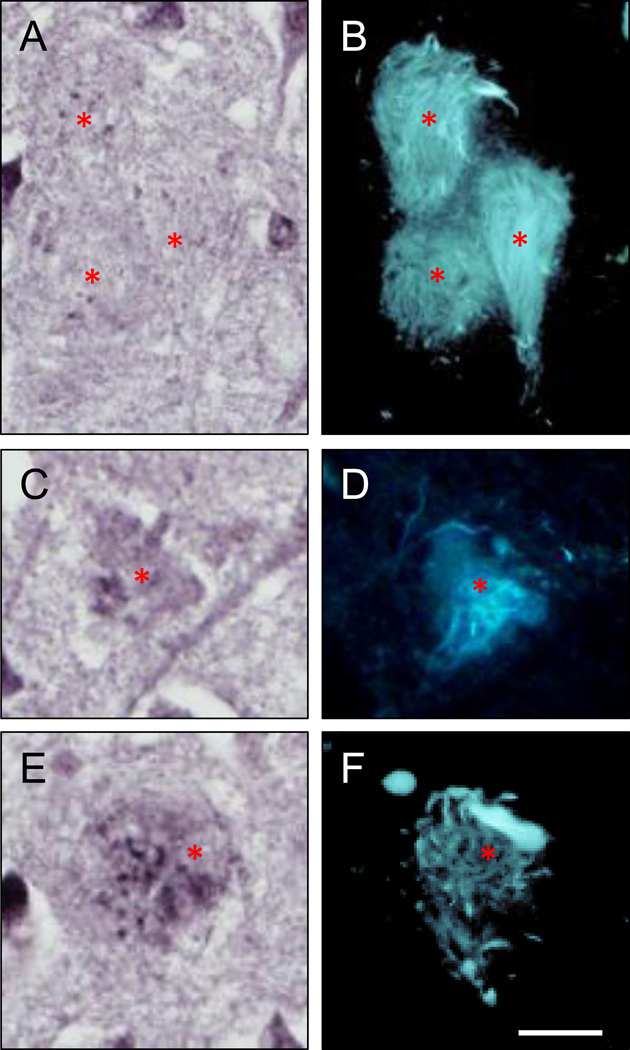

Figure 6.

Sections of an AD hippocampus (CA1 region) processed for BChE immunohistochemistry (A,C,E) and over-stained with X-34 (B,D,F) demonstrate several types of extracellular ghost NFT (eNFT; B,D,F) with variable BChE immunoreactivity. BChE immunoreactivity is not discernable in eNFT with fine and cohesive fibrillary structure (A,B) while it is prominent in eNFT with a more coarse and dispersed fibrillary structure (C–F). Asterisks mark positions of the same eNFT in BChE and X-34 preparations. Scale bar = 15 µm.

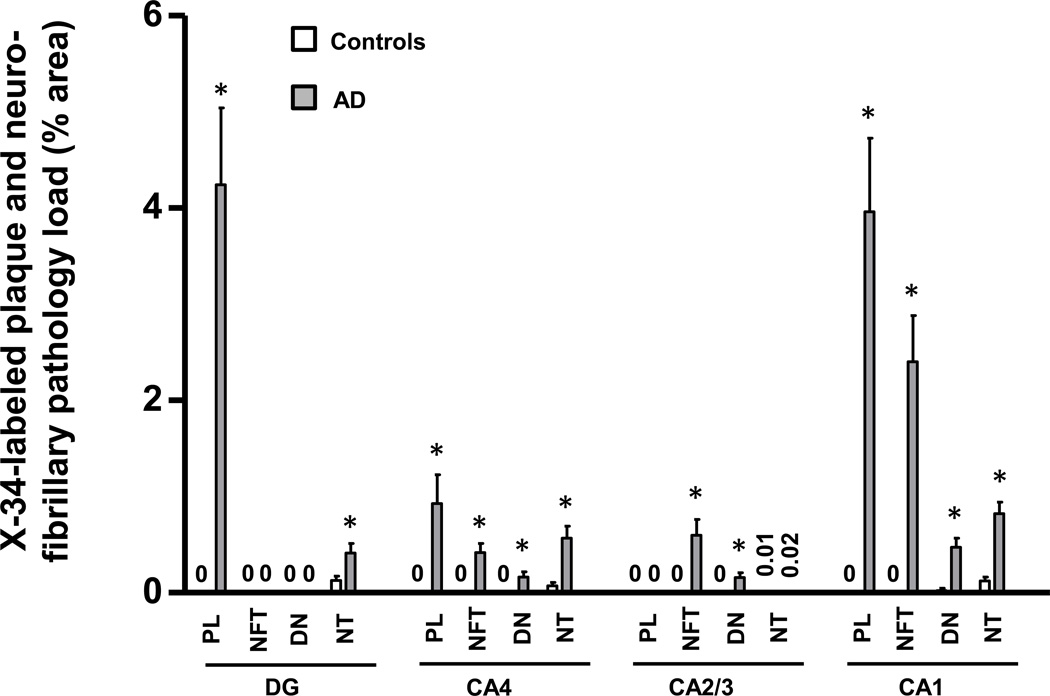

X-34 positive amyloid plaque and neurofibrillary pathology loads (% area occupied by plaques, NFT, NT, or DN) were quantified separately in hippocampal fields (Fig. 7). Consistent with neuropathological diagnosis, measures of X-34 fluorescent pathology loads were greater in AD than in controls (Fig. 7). There were several associations observed between X-34 labeled neurofibrillary pathology load measures (from Figure 7) and BChE immunoreaction intensity measures (from Figure 3). In the DG, greater X-34 labeled NT load correlated with greater BChE immunoreaction intensity in the granular cell layer (Table 2). In CA2/3, greater loads of X-34 labeled NFT and DN correlated significantly with greater intensity of BChE immunoreaction in all layers, and greater load of X-34 labeled NT correlated significantly with greater intensity of BChE immunoreaction in the pyramidal cell layer and in stratum oriens (Table 2). There were no statistically significant associations between X-34 labeled neurofibrillary pathology load and BChE immunoreaction intensity in CA4 or CA1.

Figure 7.

Bar graph illustrating plaque and neurofibrillary pathology quantified by measuring percent area occupied by X-34-labeled structures in hippocampal fields of controls (empty bars) and AD (solid bars). Abbreviations: DG, dentate gyrus; NFT, neurofibrillary tangles; DN, dystrophic neurites; NT, neuropil threads, PL, plaque load. *p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Correlation analyses of regional BChE immunoreaction intensity and X-34-labeled plaque, NFT, DN, or NT pathology loads. Spearman R (P value, two tailed).

| Regional X-34 Pathology Load |

BChE Immunoreaction Intensity (optical density in specific regional layers/structures) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DG or CA4 | DG SG | DG SM | CA4 neurons | CA4 neuropil | |

| PL | 0.46 (0.13) | 0.29 (0.36) | 0.48 (0.13) | 0.55 (0.06) | |

| NFT | None present | None present | 0.39 (0.24) | 0.37 (0.23) | |

| DN | None present | None present | 0.59 (0.054) | 0.58 (0.046) | |

| NT | 0.76 (0.0045) | 0.48 (0.12) | 0.03 (0.30) | 0.50 (0.10) | |

| CA2/3 | CA2/3 SO | CA2/3 SP neurons | CA2/3 SP neuropil | CA2/3 SR | |

| NFT | 0.83 (0.0008) | 0.88 (0.0002) | 0.85 (0.0004) | 0.77 (0.003) | |

| DN | 0.85 (0.0005) | 0.76 (0.004) | 0.76 (0.004) | 0.71 (0.0096) | |

| NT | 0.62 (0.033) | 0.69 (0.014) | 0.53 (0.079) | 0.31 (0.33) | |

| CA1 | CA1 SO | CA1 SP neurons | CA1 SP neuropil | CA1 SR | |

| PL | 0.24 (0.42) | 0.28 (0.36) | 0.49 (0.092) | 0.45 (0.12) | |

| NFT | 0.28 (.35) | 0.41 (0.16) | 0.53 (0.062) | 0.56 (0.047) | |

| DN | 0.20 (0.50) | 0.24 (0.43) | 0.39 (0.19) | 0.36 (0.22) | |

| NT | 0.08 (0.80) | 0.23 (0.45) | 0.44 (0.13) | 0.43 (0.14) | |

DG = dentate gyrus (SG = stratum granulosum, SM = stratum moleculare); DN = dystrophic neurites; NFT = neurofibrillary tangles; NT = neuropil threads; PL = plaque load; SO = stratum oriens; SP = stratum pyramidale; SR = stratum radiatum. “Neuropil” refers to the neuropil surrounding neurons in CA fields 1, 2/3, and 4.

Discussion

This study provides an antibody-based analysis of the distribution and localization of BChE in normal human hippocampus, and its alteration and relation to amyloid structure of plaques and neurofibrillary pathology in AD. While our method confirmed the presence of BChE in amyloid plaques, it also led to several novel findings including 1) BChE is not closely associated with classic NFT, in contrast to several prior reports; 2) BChE immunohistochemistry is a viable alternative to enzyme histochemical methods used previously; 3) in AD hippocampus there is selective up-regulation of BChE in the CA2/3 region, generally considered more resistant to AD pathology.

The results of our immunohistochemical analyses of BChE extend previous studies which used histochemical detection of enzyme activity to examine BChE in aged human and AD hippocampus. For example, using enzyme histochemistry, Darvesh and colleagues10 reported that BChE localized to neurons and their processes in the polymorphic layer of the dentate gyrus, as well as stratum oriens and pyramidale of the CA fields, but not in the neuropil. While our study also demonstrates the preponderance of BChE in neuronal cells, we report that neuropil contains considerable BChE immunoreactivity in all hippocampal fields. The latter may be due to BChE containing glial cell processes, as suggested by Mesulam and colleagues5. While we observed hippocampal BChE immunoreactive glial cell bodies in the stratum oriens of CA1–3 and in the white matter of the alveus, we were not able to resolve individual glial processes in the neuropil and we did not observe BChE immunoreactive glia in other hippocampal fields. In accord with our observation of BChE immunoreactive glial cells near myelinated fiber tracks in the hippocampus, Wright and colleagues27 reported that glia labeled with BChE enzyme histochemistry are abundant in deep cortical layers and white matter, in both control and AD brains. The functional significance of BChE in glia remains to be determined.

In AD cases, X-34 positive amyloid plaques in dentate gyrus molecular layer and CA fields contained clusters of BChE-immunoreactive structures resembling ballooned axonal terminals that were previously described as AChE-positive neurites in immature plaques28. These BChE containing clusters did not co-label with X-34, indicating lack of dense amyloid β-sheet structure, however their co-labeling with antibody clone AT8 suggests they contain an early (pre-fibrillar) type of phosphorylated tau aggregate. In support of our current findings, a previous immunohistochemical study in AD and nondemented control cases demonstrated that at early stages of Aβ and thioflavin-S positive plaques, associated dystrophic neurites accumulating choline acetyltransferase and several neuropeptides lacked frank evidence of neurofibrillary pathology (i.e., immunoreactivity to Alz-50 or PHF antibodies29). Thus, BChE-immunoreactive clusters in plaques could belong to degenerating cholinergic fibers, similar to those described using AChE histochemistry in AD cerebral cortex29. The cholinergic origin of the BChE-immunoreactive clusters is additionally supported by reports of similar structures detected using AChE immunohistochemistry and histochemistry in aged monkey cerebral cortex30, 31, and BChE enzyme histochemistry in AD brain14, 15, 27, 33, 34.

Our observation that the majority (>80%) of X-34 labeled amyloid plaques contained BChE is in agreement with previous reports14, 35. We also observed a small proportion of diffuse, non-neuritic X-34 plaques without BChE immunoreactive clusters. This is in agreement with histochemical studies showing incomplete overlap of AChE and BChE with diffuse (thioflavin S negative) plaques14. These and similar observations led Mesulam and colleagues to propose that plaque-associated BChE may have a role in the hypothetical conversion of diffuse plaques to compact plaques in AD36. This is a particularly compelling idea given the possibility that the enzymatic property of BChE in plaques differs from that in normal cells and axons27 and is pathologically significant36, particularly since the enzyme influences APP processing37 and might contribute to Aβ production and accumulation in AD. This is emphasized further by recently reported evidence from a GWAS study in the ADNI cohort, that variations at the BChE gene locus are associated with amyloid plaque load measured by florbetapir PET9.

Despite the presence of BChE immunoreactivity in the majority of X-34-labeled amyloid plaques, we found no significant correlation between amyloid plaque load (% area) and overall regional BChE OD intensity measures. This discrepancy could be explained by our observations that in the hippocampus 1) BChE is predominantly localized to neurons and neuropil (regardless of plaque distribution), and 2) BChE immunoreactivity in amyloid plaques is restricted to discrete clusters, whereas the entire plaque area occupied by β-sheet structure of amyloid (more dense in the compact core and less dense in the diffuse halo) is labeled with X-34. Additionally all of AD cases in the present study had an advanced stage of dementia (CDR=3) with similarly heavy plaque burdens (CERAD=B or C).

Similar to our observation of a poor co-localization of BChE and X-34 positive amyloid structure in dystrophic neurites, we found that BChE immunoreactivity co-localized with only a small proportion of X-34 positive intracellular and extracellular NFT (eNFT), some of them resembling TANC38, in AD hippocampus. These results are in agreement with several analyses of cholinesterases in eNFT which reported that cholinesterase labeling of eNFT varies at various stages of eNFT dissolution15, and that cholinesterases are associated with Aβ-immunoreactive, not tau, components of eNFT16. The overall absence of AT8 signal in BChE immunoreactive neurons, suggests that tau protein in these cells has not yet fibrilized and, accordingly, is not detectable using amyloid-binding compounds such as X-34 (pre-tangles, or early tangles). Future studies should employ a panel of antibodies against additional phosphorylated epitopes on tau, or different conformational states of the protein, to examine more closely the relationship between tau and BChE.

The finding that greater neurofibrillary pathology load correlated with higher BChE immunoreactivity in CA2/3, but not in the CA1, warrants further investigation. This regional difference may reflect better resistance of CA2/3 neurons to fibrillary tau pathology in the AD brain. Up-regulated BChE could result in less ACh at mossy fiber terminals targeting CA2/3 pyramidal cells. Given the modulatory role of ACh in glutamate release, this response could fine tune glutamate neurotransmission at the mossy fiber synapse, resulting in CA2/3 region-selective reduction in excitotoxicity. In contrast, plaque-associated BChE may have non-cholinergic functions and can be related to Aβ-containing amyloid pathology progression, as hypothesized by Geula and Mesulam39.

In conclusion, we found that in AD hippocampus, BChE-accumulating pyramidal cells and plaque-associated neuritic clusters do not contain dense amyloid structure typical of classic NFT and dystrophic neurites in neuritic plaques. However, in select areas the enzyme increase occurs in parallel with the progression of regional neurofibrillary pathology and therefore it may precede the development of amyloid aggregates or it could contribute to cells’ resistance to such pathology. The functional consequences of these observations remain to be explored and could have important clinical implications for cholinergic (BChE targeted) therapies in AD.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the subjects from Choju Medical Institute, Fukushimura Hospital and Ishizaki Hospital in this study. This work was supported by NIH grants NIA AG014449 and AG025204 (MDI), and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (KM). Ms. Lan Shao, Ms. Natsuko Kato and Ms. Megumi Mitani provided expert technical assistance.

References

- 1.Heckers S, Geula C, Mesulam MM. Acetylcholinesterase-rich pyramidal neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:455–460. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesulam MM, Geula C. Chemoarchitectonics of axonal and perikaryal acetylcholinesterase along information processing systems of the human cerebral cortex. Brain Res Bull. 1994;33:137–153. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geula C, Darvesh S. Butyrylcholinesterase, cholinergic neurotransmission and the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Drugs Today (Barc) 2004;40:711–721. doi: 10.1358/dot.2004.40.8.850473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesulam MM, Guillozet A, Shaw P, Levey A, Duysen EG, Lockridge O. Acetylcholinesterase knockouts establish central cholinergic pathways and can use butyrylcholinesterase to hydrolyze acetylcholine. Neuroscience. 2002;110:627–639. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesulam MM, Guillozet A, Shaw P, Quinn B. Widely spread butyrylcholinesterase can hydrolyze acetylcholine in the normal and Alzheimer brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:88–93. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatonnet A, Lockridge O. Comparison of butyrylcholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase. Biochem J. 1989;260:625–634. doi: 10.1042/bj2600625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartorelli L, Giraldi C, Saccardo M, et al. Effects of switching from an AChE inhibitor to a dual AChE-BuChE inhibitor in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1809–1818. doi: 10.1185/030079905X65655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greig NH, Utsuki T, Ingram DK, et al. Selective butyrylcholinesterase inhibition elevates brain acetylcholine, augments learning and lowers Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide in rodent. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:17213–17218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508575102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramanan VK, Risacher SL, Nho K, et al. APOE and BCHE as modulators of cerebral amyloid deposition: a florbetapir PET genome-wide association study. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:351–357. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darvesh S, Grantham DL, Hopkins DA. Distribution of butyrylcholinesterase in the human amygdala and hippocampal formation. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:374–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morán MA, Gómez-Ramos P. Cholinesterase histochemistry in the human brain: effect of various fixation and storage conditions. J Neurosci Methods. 1992;43:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(92)90066-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry EK, Perry RH, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE. Changes in brain cholinesterases in senile dementia of Alzheimer type. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1978;4:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1978.tb00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arendt T, Brückner MK, Lange M, Bigl V. Changes in acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in Alzheimer's disease resemble embryonic development--a study of molecular forms. Neurochem Int. 1992;21:381–396. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(92)90189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morán MA, Mufson EJ, Gómez-Ramos P. Colocalization of cholinesterases with beta-amyloid protein in aged and Alzheimer's brains. Acta Neuropathol. 1993;85:362–369. doi: 10.1007/BF00334445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morán MA, Mufson EJ, Gómez-Ramos P. Cholinesterases Colocalize with sites of neurofibrillary degeneration in aged and Alzheimer's brains. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;87:284–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00296744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cebrián JL, Morán MA, Gómez-Ramos P. Association of cholinesterases with amyloid in extracellular neurofibrillary tangles. Brain Res. 1997;19:173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00843-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zwan MD, Okamura N, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Furumoto S, Masters CL, Rowe CC, Villemagne VL. Voyage au bout de la nuit: Aβ and tau imaging in dementias. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;58:398–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders IV. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwakiri M, Mizukami K, Ikonomovic MD, et al. An immunohistochemical study of GABA A receptor gamma subunits in Alzheimer's disease hippocampus: relationship to neurofibrillary tangle progression. Neuropathology. 2009;29:263–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2008.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizukami K, Ishikawa M, Akatsu H, Abrahamson EE, Ikonomovic MD, Asada T. An immunohistochemical study of the serotonin 1A receptor in the hippocampus of subjects with Alzheimer's disease. Neuropathology. 2011;31:503–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2010.01193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duvernoy HM. The Human Hippocampus. New York: Springer Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Styren SD, Hamilton RL, Styren GC, Klunk WE. X-34, a fluorescent derivative of Congo red: a novel histochemical stain for Alzheimer's disease pathology. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:1223–1232. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikonomovic MD, Abrahamson EE, Isanski BA, et al. X-34 labeling of abnormal protein aggregates during the progression of Alzheimer's disease. Methods Enzymol. 2006;412:123–144. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)12009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright CI, Geula C, Mesulam MM. Neuroglial cholinesterases in the normal brain and in Alzheimer's disease: relationship to plaques, tangles, and patterns of selective vulnerability. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:373–384. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tago H, McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Acetylcholinesterase fibers and the development of senile plaques. Brain Res. 1987;406:363–369. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90808-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benzing WC, Ikonomovic MD, Brady DR, Mufson EJ, Armstrong DM. Evidence that transmitter-containing dystrophic neurites precede paired helical filament and Alz-50 formation within senile plaques in the amygdala of nondemented elderly and patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Comp Neurol. 1993;334(2):176–191. doi: 10.1002/cne.903340203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGeer EG, McGeer PL, Kamo H, Tago H, Harrop R. Cortical metabolism, acetylcholinesterase staining and pathological changes in Alzheimer's disease. Canad J Neurol Sci. 1986;13:511–516. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100037227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitt CA, Price DL, Struble RG, et al. Evidence for cholinergic neurites in senile plaques. Science. 1984;226:1443–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.6505701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Struble RG, Cork LC, Whitehouse PJ, Price DL. Cholinergic innervation in neuritic plaques. Science. 1982;216:413–415. doi: 10.1126/science.6803359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geula C, Mesulam MM. Special properties of cholinesterases in the cerebral cortex of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 1989;498:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guillozet AL, Smiley JF, Mash DC, Mesulam MM. Butyrylcholinesterase in the life cycle of amyloid plaques. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:909–918. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eskander MF, Nagykery NG, Leung EY, Khelghati B, Geula C. Rivastigmine is potent inhibitor of acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase in Alzheimer's plaques and tangles. Brain Res. 2005;1060:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mesulam MM, Geula C. Butyrylcholinesterase reactivity differentiates the amyloid plaques of aging from those of dementia. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:722–727. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Small DH, Moir RD, Fuller SJ, et al. A protease activity associated with acetylcholinesterase releases the membrane-bound form of the amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10795–10799. doi: 10.1021/bi00108a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munoz DG, Wang D. Tangle-associated neuritic clusters. A new lesion in Alzheimer's disease and aging suggests that aggregates of dystrophic neurites are not necessarily associated with beta/A4. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:1167–1178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geula C, Mesulam MM. Cholinesterases and the pathology of Alzheimer disease. Alz Dis Assoc Dis. 1995;9:23–28. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199501002-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]