Many expected that the splendid and remarkable success of statins and other preventive measures introduced towards the end of the 20th century would halt the epidemic of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.1 Yet, rather than receding globally, the burden of ischemic cardiovascular conditions has risen to become a top cause of morbidity, loss of useful life years, and mortality worldwide.2 As developing countries have undergone the “epidemiologic transition,” communicable diseases have receded, and chronic diseases, notably those due to atherosclerosis and hypertension, have become dominant public health problems, like in the United States and Europe, as discussed in this compendium.3,4

Even with access to the highest technology and most recently available secondary prevention therapies, the burden of recurrent events following acute coronary syndromes remains unacceptable, on the order of 10% in the first 12 months despite optimal treatment with contemporary intervention and pharmacologic agents.5–7 Thus, on a clinical basis and as a public health challenge, atherosclerosis remains high on the list of global challenges to long and healthy lives.

Simultaneously, laboratory research has continued to unravel successive layers of the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and the mechanisms of its clinical complications. These advances have not only deepened our appreciation for the subtlety of atherogenesis, they have also provided us with many surprises that have challenged numerous previously cherished notions, and have allowed the development of new therapeutic approaches to combat cardiovascular disease.

Hence the need for a compendium of articles that reviews the current state-of-the-art of atherosclerosis research spanning from a global health perspective to fundamental molecular mechanisms. The editors intend this collection of articles not only to celebrate the successes, but also to highlight the emerging challenges to many tenets of belief that have emerged from recent studies. We do so in the spirit of inspiring future research to attack the unresolved questions and to exploit the newer discoveries that have opened unanticipated horizons of understanding and raised novel questions and opportunities for therapies.

Herrington and colleagues lead off the compendium with an update of the epidemiology of atherosclerosis, the changing face of atherothrombotic disease in the clinic, and the global reach of this epidemic.4 Nordestgaard then discusses emerging epidemiologic findings regarding lipoprotein risk factors, highlighting new genetic, epidemiologic, and mechanistic information regarding the importance of triglyceride and cholesterol-rich remnant lipoproteins.8

The last several decades witnessed an era of smaller studies that assessed the association of single nucleotide polymorphisms with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. This approach yielded little fruit, as few if any of the results proved generalizable or replicable.9 The advent of more comprehensive approaches such as genome–wide association scans (GWAS) and Mendelian randomization analyses ushered in a new era that has provided reproducible, and in some cases furnished eye–opening, results. Contemporary genetics has buttressed the causal role of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in atherogenesis, but also identified new targets that may revolutionize the therapy of this risk factor. The review by McPherson and Thyberg–Hansen summarizes some of the advances in the genetics of coronary heart disease (CHD).10 Kathiresan and Musunuru highlight surprises that have arisen from genetic analyses of lipid risk factors, providing an independent support for some of the epidemiologic findings presented by Nordestgaard.11 Some of the genetic factors that have emerged from contemporary analyses affirm risk factors previously recognized as pathogenic based on prior knowledge, such as increased levels of LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and hypertension. Yet, there is little or no overlap between the lists of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with HDL cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, or chronic kidney disease and those linked to CHD, a conundrum that remains largely unexplained.

Furthermore, approximately 75% of the CHD SNPs occur in or near genes with no obvious connections to atherothrombosis, and the relevant genes and their functions remain obscure. While holding promise for the identification of new pathways and targets for treatment, the challenge of linking genetic variants to biological functions and therapeutics represents a significant hurdle. Rader and colleagues outline approaches to linking SNPs to genes and their functions, including new tools from genomics and novel experimental approaches in cells and animals.12 They discuss a few specific examples where GWAS “hits” have led to new insights into the role of specific genes in atherogenesis. For the most part, however, the new genetic information lacks integration into the cell biology of atherosclerosis. Pursuing the biological implications of the emerging genetic results represents a promising area for future investigation.

The availability of validated genetic markers has raised the possibility of their clinical application in risk stratification and to targeting therapy in a personalized or precision medicine mode. Indeed, as discussed by McPherson and Tybjaerg-Hansen, genetic risk scores may predict who will benefit most from statin therapy.10, 13 Paynter and colleagues provide a broad and balanced discussion of the current utility and challenges of the application of genetics in the clinic, including the usefulness of genetic information in risk prediction and pharmacogenomic determinants of the response to therapies for atherothrombosis.14

Advances in the cell biology of atherosclerosis and its pathogenesis have also yielded advances and surprises. The endothelial cell, relegated to a gatekeeper barrier function for much of the last century, has emerged as the defender of vascular homeostasis as described by Gimbrone and Garcia-Cardeña in a masterful review that covers the history of contemporary endothelial biology in the context of atherogenesis, and brings us up to date with the latest discoveries in this regard.15 Endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis extends beyond impaired vasodilator capacity, and also involves disturbances in anti-thrombotic, pro-fibrinolytic, and anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties of the normal endothelium.

We have learned that the myeloid cells involved in atherosclerosis have functionally important diversity. These foot soldiers of the innate immune response may also instruct the adaptive immune system. The delicate duet between innate and adaptive immunity likely provides major modulatory influences on the disease. The contributions of Cybulsky and colleagues,16 Tabas and Bornfeldt,17 and Ketelhuth and Hansson18 delve into the intricacies of cellular and humoral immunity and of myeloid cells and mononuclear phagocytes. In particular, Cybulsky, Cheong, and Robbins contrast the functional palettes of monocytes, macrophages residing in the adventitial versus intimal layers of arteries, and dendritic cells, in atherosclerosis.16 They underline the need for the use of multiple cell surface markers, transcription factor expression, and transcriptional profiling to distinguish and understand functionally distinct cell populations.

Tabas and Bornfeldt highlight the fates of these important cells in different stages of atherosclerosis.17 They review the functional programs and roles of lesional macrophages, and argue that mononuclear phagocytes functions reflect the microenvironment in the atheroma. They argue that the field has moved beyond this relatively simple boxing of macrophage functions into “M1” and “M2” categories. Rather, macrophage character depends on a plethora of pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators present in lesions, which involve multiple signal transduction pathways and downstream effects in macrophages, leading to increased inflammatory activation or resolution of the inflammatory process. Macrophage functions also depend on the balance of lipids in different cellular compartments, and the metabolic demands on the macrophage. The different functional attributes of macrophages influence the initiation of lesions, their progression to advanced atheromata, their complication, and their responses to therapies.

The review provided by Sorci-Thomas and Thomas highlights the interface between immune cell lipid loading, cellular cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains, and inflammation.19 Recent research has revealed dynamic regulation of the balance between free cholesterol in cellular membrane microdomains and esterified cholesterol in lipid droplets, in part governed by lipoproteins and cellular cholesterol exporters. Increased free cholesterol in immune cells provides important links to inflammation by promoting receptor over-sensitization, leading to hematopoietic stem cell proliferation, leukocytosis, and T cell activation. These links among lipoproteins, cellular cholesterol, and inflammation likely influence not only atherosclerosis but also autoimmune diseases. Together, the recent discoveries related to myeloid cells and other immune cells involved in atherosclerosis have highlighted potential targets for therapeutic intervention ranging from vaccination to anti–cytokine treatments.

The study of smooth muscle cells, traditionally considered a specialized relative of fibroblasts, has also yielded surprises.20 Recent results have raised important questions about the very identity of smooth muscle cells, and suggested unanticipated transmutability between cells that we have traditionally labeled as vascular smooth muscle cells and mononuclear leukocytes. These recent findings provide a stark contrast with previous notions. Much work in the last quarter of the 20th century focused on smooth muscle cell proliferation and even proposed a monoclonal or monotypic replication of the cells as paramount in atherogenesis, a notion quite contrary to the current recognition of the developmental and functional diversity of these cells.21 Early formulations of the “response to injury” hypothesis of atherogenesis viewed it as a bland process rooted in inappropriate proliferation of smooth muscle cells.22, 23 Bennett, Sinha, and Owens provide a fascinating review of new concepts in vascular smooth muscle cell biology in relation to atherosclerosis. They explicate the dynamic and diverse properties of smooth muscle cells, including smooth muscle cell embryological origin, phenotype switching, conversion of smooth muscle cells to macrophage-like cells, and the roles of smooth muscle cell proliferation, apoptosis, and senescence in different phases of atherosclerosis.20 Smooth muscle cell biology has regained a central place at the cutting edge of atherosclerosis research.

Results of recent laboratory studies have uncovered regulatory mechanisms pertinent to atherogenesis undreamed of only a few decades ago. The role of non-coding small RNAs (micro-RNAs) as “fine-tuners” of atherosclerotic progression and regression and lipid metabolism has opened entirely new vistas on the molecular pathways that control this disease, as reviewed by Feinberg and Moore.24 As in the case of mRNAs, cytokines, shear-stress, and other atherogenic mediators regulate micro-RNA concentrations. Micro-RNAs control all major cell types involved in atherosclerosis, and participate in cell-to-cell communication. Furthermore, emerging research suggests that plasma micro-RNAs can serve as biomarkers of cardiovascular disease diagnosis, prognosis, and pharmacological treatment effectiveness. The coming years are certain to bring new and exciting discoveries related to non-coding RNAs and RNA therapeutics with respect to atherosclerosis.

From a therapeutic standpoint, we have much to celebrate, and much to anticipate. Harnessing the results of experimental laboratory research may yield even further advances in treatments. Pedersen describes from an “eye–witness” perspective the success story of LDL cholesterol lowering.25 Shapiro and Fazio look beyond statins, and discuss new avenues to reducing atherosclerotic risk not only by targeting lipids with novel interventions, but also by reaching beyond targeting traditional risk factors to new approaches based on anti-inflammatory therapies.26

To guide, inform, and validate novel therapies Rudd and colleagues contribute a comprehensive review of the burgeoning imaging approaches to the visualization of atherosclerosis.27 Only a few decades ago, the luminogram visualized by arteriography provided the “gold standard” for atherosclerosis imaging. We now stand on the threshold of an era where we can not only image the lesion itself rather than the lumen, but also particular cells, molecular mediators, and cellular functions relevant to disease pathogenesis.

The advances described in the articles included in this compendium celebrate the strides made in understanding atherosclerosis in recent decades. We highlight the novel, the unsuspected, the contrarian, and the challenging. Despite this ferment in the field, many questions remain unanswered and provide fertile ground for future research. For example, the simple notion that increasing HDL cholesterol levels would consistently reduce atherosclerosis risk has faced challenges from disappointing clinical trials and Mendelian randomization analyses.11 Notwithstanding, the ascertainment of HDL functions such as cholesterol efflux potential and of HDL particle number, and therapeutic approaches that increase these variables warrant continued investigation. In particular, some approaches to increasing HDL function or promoting reverse cholesterol transport using HDL mimetics or infusions of apolipoprotein A1 or its variants merit continued consideration.

New data regarding the pathogenicity of triglyceride-rich type lipoproteins have rekindled interest in the functional roles of Apolipoproteins V and C3, and the new players, Angptl3 and Angptl4.11 These findings have stimulated renewed efforts to target therapeutically triglycerides or perhaps more specifically cholesterol-rich remnant lipoproteins.8 Lipoprotein (a) has emerged as a likely causative agent in atherothrombosis from GWAS and Mendelian randomization analyses.10

The accumulating information implicating inflammatory pathways as links between traditional and emerging risk factors and atherosclerosis and its complications have led to trials that target these pathways therapeutically. Large-scale clinical outcome studies currently underway use a monoclonal antibody that neutralizes interleukin 1β or weekly administration of low–dose methotrexate.28, 29 In view of the redundancy of inflammatory signaling and its importance in maintaining host defenses, the application of anti-inflammatory interventions may require targeted efforts to find the “sweet spot” that will quell disease–relevant information without impairing tumor surveillance or defenses against infection. In this regard, harnessing advances in understanding mediators of the resolution of inflammation that do not per se have anti-inflammatory actions merits further development.30

Ultimately, we must strive to reach beyond the experimental laboratory and biomarkers or observational studies, and test hypotheses in humans that have emerged from the advances in basic research. The critical importance of properly designed and powered clinical trials has become even more evident given the surprises that emerge from such undertakings. Clinical trials require daunting resources, as standard of care therapies have reduced event rates, demanding larger and longer studies to demonstrate incremental benefit. We need to extend clinical trials globally, to address the growing problem of cardiovascular disease worldwide.4 We also need to reach beyond a “one size fits all” approach and to develop “smarter” trial designs, including the judicious use of biomarkers and genetic information to target therapies towards those who are most likely to benefit from treatment to enhance their likelihood of success, and to achieve the goal of precision medicine in the future management of atherosclerotic risk in our patients. We trust that the papers assembled in this compendium will prove useful in spurring and informing this future progress.

Supplementary Material

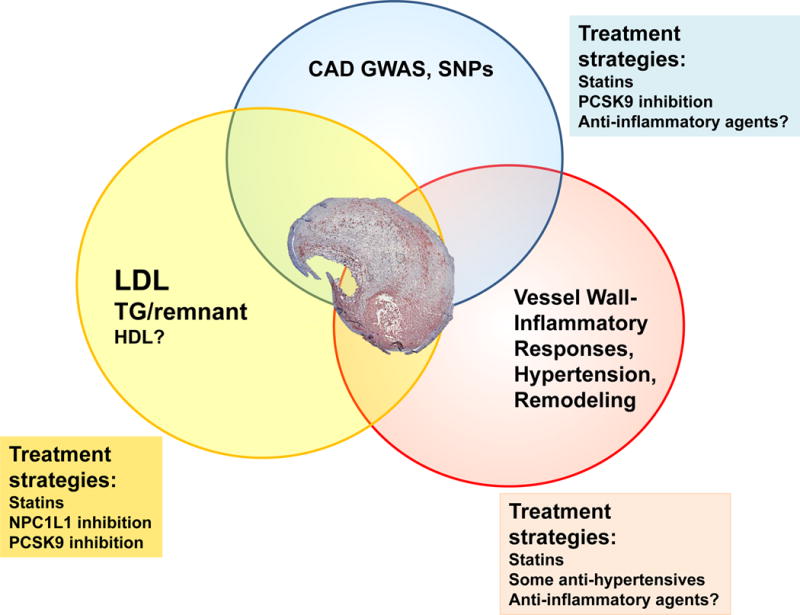

Figure 1. Interplay among processes associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk and treatment strategies targeting these processes.

The review articles included in this compendium provide a comprehensive overview of the state of the atherosclerosis research area today and some of its history. Recent progress has advanced three major areas related to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk: the roles of lipoproteins (LDL, TG-rich remnant lipoproteins and HDL); identification of genes associated with cardiovascular disease risk through GWAS; and further elucidation of local processes in the artery wall. These three areas exhibit significant overlap as demonstrated by the Venn diagram. Treatment strategies targeting lipoproteins and several of the genes identified by GWAS include statins and the recently approved PCSK9 inhibitors. Anti-inflammatory agents might target inflammatory genes identified by GWAS. Anti-inflammatory agents, as well as anti-hypertensive agents may also modulate atherogenic processes locally in the artery wall.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ laboratories are funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01HL062887, R01HL126028, P01HL092969, HL107653, HL087123, HL119830, P30DK017047, DP3DK108209), the American Heart Association (14GRNT20410033), and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL080472).

References

- 1.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Heart attacks: gone with the century? Science. 1996;272:3. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics- 2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrington W, Lacey B, Sherliker P, Armitage J, Lewington S. The epidemiology of atherosclerosis and the potential to reduce the global burden of atherothrombotic disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307611. [in this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, Mahaffey KW, Scirica BM, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington RA, Investigators P. Freij A, Thorsen M. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:1045–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Bassand JP, Bhatt DL, Bode C, Burton P, Cohen M, Cook-Bruns N, Fox KA, Goto S, Murphy SA, Plotnikov AN, Schneider D, Sun X, Verheugt FW, Gibson CM, Investigators AAT Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jernberg T, Hasvold P, Henriksson M, Hjelm H, Thuresson M, Janzon M. Cardiovascular risk in post-myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real world data demonstrate the importance of a long-term perspective. European Heart Journal. 2015;36:1163–70. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordestgaard BG. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins: New lessons from genetics. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306249. [in this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan TM, Krumholz HM, Lifton RP, Spertus JA. Nonvalidation of reported genetic risk factors for acute coronary syndrome in a large-scale replication study. Jama. 2007;297:1551–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.14.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McPherson R, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Genetics of coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306566. [in this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Musunuru K, Kathiresan S. Surprises from genetic analyses of lipid risk factors for atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306398. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nurnberg S, Zhang H, Hand N, Bauer R, Saleheen D, Rader D, Reilly M. From loci to biology: functional genomics of genome-wide association for coronary disease. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306464. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mega JL, Stitziel NO, Smith JG, Chasman DI, Caulfield MJ, Devlin JJ, Nordio F, Hyde CL, Cannon CP, Sacks FM, Poulter NR, Sever PS, Ridker PM, Braunwald E, Melander O, Kathiresan S, Sabatine MS. Genetic risk, coronary heart disease events, and the clinical benefit of statin therapy: an analysis of primary and secondary prevention trials. Lancet. 2015;385:2264–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61730-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paynter NP, Ridker PM, Chasman DI. Are genetic tests for atherosclerosis ready for routine clinical use? Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306360. [in this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gimbrone MA, Jr, Garcia-Cardena G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306301. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cybulsky MI, Cheong C, Robbins CS. Macrophages and dendritic cells - partners in atherogenesis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306542. [in this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabas I, Bornfeldt KE. Macrophage phenotype and function in different stages of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306256. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ketelhuth DFJ, Hansson GK. Adaptive response of T and B cells in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306427. [in this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorci-Thomas MG, Thomas MJ. Microdomains, inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306246. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett MR, Sinha S, Owens GK. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306361. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benditt EP. Evidence for a monoclonal origin of human atherosclerotic plaques and some implications. Circulation. 1974;50:650–2. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.50.4.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross R, Glomset JA. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis I. New England Journal of Medicine. 1976;295:369–377. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608122950707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross R, Glomset JA. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis II. New England Journal of Medicine. 1976;295:420–425. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608192950805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feinberg MW, Moore KJ. MicroRNA regulation of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306300. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedersen TR. The success story of LDL cholesterol lowering. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306297. [in this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shapiro MD, Fazio S. From lipids to inflammation – new approaches to reducing atherosclerotic risk. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306471. [in this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarkin JM, Dweck MR, Evans NR, Takx RAP, Brown AJ, Tawakol A, Fayad ZA, Rudd JHF. Imaging atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2016;118:xxx–xxx. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306247. [in this issue] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridker PM, Howard CP, Walter V, Everett B, Libby P, Hensen J, Thuren T. Effects of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on hemoglobin A1c, lipids, C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and fibrinogen: a phase IIb randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation. 2012;126:2739–2748. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.122556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Everett BM, Pradhan AD, Solomon DH, Paynter N, MacFadyen J, Zaharris E, Gupta M, Clearfield M, Libby P, Hasan AAK, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. Rationale and design of the cardiovascular inflammation reduction trial: A test of the inflammatory hypothesis of atherothrombosis. Am Heart J. 2013;166:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Libby P, Tabas I, Fredman G, Fisher EA. Inflammation and its resolution as determinants of acute coronary syndromes. Circulation Research. 2014;114:1867–1879. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.