Abstract

Objectives

To examine the burden of comorbidity, polypharmacy and herpes zoster (HZ), an infectious disease, and its main complication post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) in young (50–70 years of age: 70−) and old (≥70 years of age: 70+) patients.

Design

Post hoc analysis of the results of the 12-month longitudinal prospective multicentre observational ARIZONA cohort study.

Settings and participants

The study took place in primary care in France from 20 November 2006 to 12 September 2008. Overall, 644 general practitioners (GPs) collected data from 1358 patients aged 50 years or more with acute eruptive HZ.

Outcome measures

Presence of HZ-related pain or PHN (pain persisting >3 months) was documented at day 0 and at months 3, 6, and 12. To investigate HZ and PHN burden, pain, quality of life (QoL) and mood were self-assessed using validated questionnaires (Zoster Brief Pain Inventory, 12-item Short-Form health survey and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, respectively).

Results

As compared with younger patients, older patients more frequently presented with comorbidities, more frequently took analgesics and had poorer response on all questionnaires, indicating greater burden, at inclusion. Analgesics were more frequently prescribed to relieve acute pain or PHN in 70+ than 70− patients. Despite higher levels of medication prescription, poorer pain relief and poorer response to all questionnaires were reported in 70+ than 70− patients.

Conclusions

Occurrence of HZ and progression to PHN adds extra burden on top of pharmacological treatment and impaired quality of life, especially in older patients who already have health problems to cope with in everyday life.

Keywords: GERIATRIC MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

One of the strengths of the study was its longitudinal design (1-year long), starting with patients with acute eruptive herpes zoster (HZ).

Its other strengths were that it was implemented in primary care, the first-line setting in real life for HZ management and included a large number of patients (n=1358).

Its first limitation was the modality of data collection for follow-up (telephone contact).

Another limitation was the absence of data on the cognitive and communication profile of included patients.

Finally, the study was not stratified on different ethnic groups, who may behave differently in terms of HZ pain sensitisation.

Introduction

Shingles, or herpes zoster (HZ), is caused by reactivation, many years later, of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) from a latent infection in the dorsal root ganglion. Since varicella is very common, 95% of the population is at risk of HZ, and HZ affects millions of persons every year.1–7 The lifetime risk of developing HZ in the general population is 25–30%, but rises to 50% in patients aged over 85 years. All epidemiological studies concur in stressing the negative short-term and long-term impact of HZ, mostly because of deleterious pain.8 9 In 10% to 15% of patients, HZ-related pain does not disappear after the florid stage of the disease but progresses towards post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN). This proportion reaches 30% in patients aged 70 years or more.5 PHN is a neuropathic pain syndrome usually defined as chronic pain persisting for more than 3 months after rash onset. It has been clearly shown that increasing age is associated with increased frequency and severity of HZ and PHN.10–12 This observation has major clinical relevance in elderly and very elderly persons, as first-line treatment in the acute phase of HZ and in PHN remains pharmacological.

Occurrence of HZ adds a supplementary difficulty to pre-existing comorbidity and polypharmacy in the context of elderly patients whose homeostatic mechanisms may already be weakened by ageing and/or concomitant disease.13 14 Ageing is associated with functional decline15 and elderly persons present a range of comorbidities that require adapted medication, leading to polypharmacy and possible drug-related adverse events and interactions.16–18 Very few studies have, however, focused on the impact of HZ and HZ-related pain in the elderly.12 19 The 12-month prospective observational ARIZONA study12 was conducted in more than 1000 primary care patients aged over 50 years with acute eruptive HZ, and evaluated the impact of HZ, HZ-related pain and PHN in real life as perceived by the patients, including quality of life (QoL). It provided valuable information that, at each time point (month 3 (M3), M6, M9 and M12), the prevalence of PHN was higher in patients aged 70 years or more (70+) than in younger patients (50–70 years of age: 70−) (p<0.05 at M3, M6, M9 and p=0.06 at M12). At M12, 6% of all patients in the study (≥50 years old) reported PHN: 4.8% in 70− patients and 7.7% in 70+ patients of age.

The present study is a post hoc analysis of this large study. The objective of the analysis was to examine the burden of comorbidity and polypharmacy in the context of pain and functional decline associated with HZ and PHN in young (70−) and old (70+) patients.

Methods

The study was a post hoc analysis of the results obtained during the 12-month longitudinal prospective multicentre observational ARIZONA cohort study. The ARIZONA study took place in primary care in France from 20 November 2006 to 12 September 2008. It has been fully described elsewhere.12 Briefly, the study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2004). According to French regulation on observational studies, the study protocol was approved by the Advisory committee on research information processing in Health (CCTIRS) on 11 January 2007 (No. 06.395bis) and by the Information Technology and Freedom Committee (CNIL) on 15 February 2007 (No.: 906270). All patients provided written informed consent before enrolment. Almost 30 000 family doctors (general practitioners (GPs)) across all regions of metropolitan France were randomly selected and invited by mail to participate in the study; 1759 agreed to take part, and 644 participated. Patients aged 50 years or more with acute HZ in the eruptive phase (defined in this study as visible skin lesions at any stage of development) and presenting to the GP within 7 days of rash onset were eligible for inclusion in the study. At inclusion (day 0: D0), GPs collected information on the patients (including traumatic life events classified in seven major categories: personal and family health problems; stress; family problems; divorce/separation; occupational difficulty; other), their disease, the neuropathic nature of pain, using the Douleur Neuropathique en 4 Questions questionnaire (DN4),12 and prescribed HZ treatments. GPs were then contacted by telephone at M3, M6 and M12 to collect information on persistent zoster-related pain, clinical pathway and treatment. At D0, HZ burden (pain, QoL and mood) was self-assessed by the patients using validated questionnaires: the Zoster Brief Pain Inventory (ZBPI), 12-item Short-Form health survey (SF12) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).20–22 The SF12 and HADS were completed at M3, M6 and M12 by all included patients, and the ZBPI by patients with PHN. Patient information was obtained by telephone interviews conducted by trained interviewers.

All statistical analyses used SAS software, V.8.02 (SAS, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Quantitative variables were described by frequency, mean, SD, median and range. Qualitative variables were described by the frequency and percentage of each modality. For qualitative variables, Fisher's exact and χ2 tests were used to compare groups. Univariate analyses were performed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) (time×age in 2 classes) was performed, with the significance threshold set at <0.05.

Results

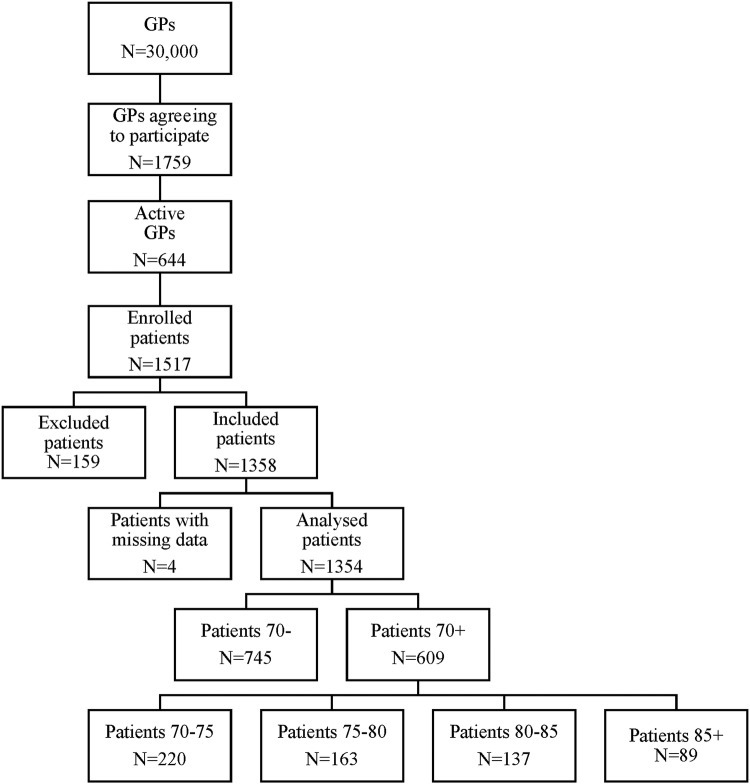

Between June 2007 and June 2008, 1517 patients were enrolled in the study, of whom 1358 (89.5%) satisfied the inclusion criteria. A total of 1354 patients had data (including age) available on D0, and were included in the analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. GPs, general practitioners.

At D0, the mean age of patients was 67.7 years (range: 50–95): 55% 70− and 45% 70+, including 37.1%≥80 years and 14.6%≥85 years (figure 1). Most patients were women in both groups: 61.2% of 70− and 62.2% of 70+ patients.

At M3, M6 and M12, respectively, PHN was present in 14.3%, 10.4% and 7.7% of 70+ patients who answered the questionnaire item (n=627, 608 and 544, respectively) and in 9.7%, 7.2% and 4.8% of 70− patients who answered the questionnaire item (n=462, 442 and 393, respectively).

As compared with the other patients, 70+ patients more frequently reported at least one comorbidity at diagnosis (77.1% vs 49.1%, table 1). Cardiovascular disease was the most frequently reported comorbidity. Its prevalence was particularly high in the 80–85 (80.9%) and 85+ (78.6%) age groups. Immune deficiency was rare, reported by 2.7% of patients, but increased in the 80–85 (5.1%) and 85+ (5.6%) age groups.

Table 1.

Comorbidities at inclusion according to age

| Comorbidities |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | At least one comorbidity (%) | Cardiovascular disease (%) | Diabetes (%) | Cancer (%) | Chronic pulmonary disease (%) | Other chronic diseases (%) |

| 70− (N=745)* | 49.1 | 51.1 | 16.5 | 14.0 | 8.5 | 33.0 |

| 70+ (N=609)† | 77.1 | 72.5 | 13.3 | 8.6 | 11.6 | 28.6 |

| 70–75 (N=220) | 72.8 | 73.2 | 17.3 | 11.0 | 12.6 | 24.4 |

| 75–80 (N=163) | 78.4 | 80.9 | 9.1 | 4.5 | 10.9 | 28.2 |

| 80–85 (N=137) | 81.5 | 80.9 | 9.1 | 4.5 | 10.9 | 28.2 |

| 85+ (N=89) | 78.7 | 78.6 | 12.9 | 11.4 | 14.3 | 25.7 |

*Missing information: 2 patients.

†Missing information: 6 patients.

Personal traumatic life events were present at D0 in 24.0% of patients (28.1% female; 17.1% male), irrespective of the age group (70−: 23.8%; 70+: 24.4%). Serious health problems (36.3%), death in the family (24.3%), stress (10.1%), divorce/separation (10.8%), occupational difficulty (3.2%) and other (4.5%) traumatic events were reported.

At D0, 98.5% of patients were receiving at least one drug; 94.1% were prescribed antiviral drugs, 83% analgesics, 10.1% anxiolytics, 6.8% soporifics, 2.4% antidepressants and 2.4% anticonvulsants. Antivirals, soporifics and anxiolytics were similarly prescribed in both age groups (χ2 test, p=0.407, p=0.507 and p=0.966, respectively). Analgesics (χ2 test, p=0.002), antidepressants (χ2 test, p=0.050) and local antiseptics (χ2 test, p=0.049) were more frequently prescribed in patients in the 70+ than 70− age group (table 2).

Table 2.

Drug prescription at inclusion

| <70 years (70−) | ≥70 years (70+) | χ2 (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antivirals | 686 (93.6%) | 568 (94.7%) | 0.407 |

| Analgesics | 587 (80.1%) | 519 (86.5%) | 0.002 |

| Local antiseptics | 531 (72.4%) | 463 (77.2%) | 0.049 |

| Soporifics | 47 (6.4%) | 44 (7.3%) | 0.507 |

| Anxiolytics | 74 (10.1%) | 61 (10.2%) | 0.966 |

| Antidepressants | 23 (3.1%) | 9 (1.5%) | 0.050 |

| Other treatments | 44 (6.0%) | 28 (4.7%) | 0.283 |

76.7%, 69.6% and 72.9% of patients with PHN were prescribed analgesic treatment at M3, M6 and M12, respectively (table 3). The rate of analgesic prescription in patients with PHN was higher in the 70+ than 70− age group, especially for anticonvulsants (clonazepam, gabapentin or pregabalin). At D0, these three drugs were prescribed to 9.8% of patients. At M3, M6 and M12, they were prescribed to 35.3%, 40.8% and 27.0% of 70+ patients with PHN versus 30.0%, 15.0% and 18.2% of 70− patients with PHN (χ2 test: p=0.039 M6). Anticonvulsants were the most frequent treatment in patients aged over 80 years at M6 and M12 (table 3).

Table 3.

Additional analgesic treatments

| Population |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <70 years (70−) |

≥70 years (70+) |

All |

|||||

| N=745 |

N=609 |

N=1354 |

|||||

| Additional analgesic treatment | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | p Value |

| Day 0 | |||||||

| Analgesics | 569 | 96.9 | 499 | 96.1 | 1072 | 96.6 | 0.473* |

| Antidepressants | 6 | 1.0 | 6 | 1.2 | 12 | 1.1 | 0.830* |

| Anticonvulsants | 57 | 9.7 | 51 | 9.8 | 108 | 9.7 | 0.948* |

| Month 3 | |||||||

| Analgesics | 46 | 76.7 | 78 | 76.5 | 125 | 76.7 | 0.977* |

| Antidepressants | 4 | 6.7 | 6 | 5.9 | 10 | 6.1 | 0.841* |

| Anticonvulsants | 18 | 30.0 | 36 | 35.3 | 54 | 33.1 | 0.605† |

| Month 6 | |||||||

| Analgesics | 17 | 85.0 | 31 | 63.3 | 48 | 69.6 | 0.075* |

| Antidepressants | 3 | 15.0 | 2 | 4.1 | 5 | 7.2 | 0.142† |

| Anticonvulsants | 3 | 15.0 | 20 | 40.8 | 23 | 33.3 | 0.039* |

| Month 12 | |||||||

| Analgesics | 8 | 72.7 | 27 | 73.0 | 35 | 72.9 | 1.000† |

| Antidepressants | 2 | 18.2 | 6 | 16.2 | 8 | 16.7 | 1.000† |

| Anticonvulsants | 2 | 18.2 | 10 | 27.0 | 12 | 25.0 | 0.705† |

| <80 years (80−) |

≥80 years (80+) |

All |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=745 |

N=609 |

N=1354 |

|||||

| Anticonvulsants | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | p Values |

| Month 3 | 40 | 32.5 | 14 | 35.9 | 54 | 33.1 | 0.697* |

| Month 6 | 14 | 26.9 | 9 | 52.9 | 23 | 33.3 | 0.048* |

| Month 12 | 7 | 21.9 | 5 | 31.3 | 12 | 25.0 | 0.500† |

*χ2 test.

†Fischer's exact test.

At 1 year follow-up, the proportion of patients receiving pain treatment was higher in the 70+ than 70− age group (61.1% vs 35.7%, respectively: p<0.01).

ZBPI, SF12 and HADS scores were poorer in patients with pain and in the 70+ than 70− age group. In patients with pain (acute at D0, and PHN at M3, M6 and M12), the ZBPI interference score and the scores for daily life activities items (general activity, walking, sleep, enjoyment of life) were usually higher (indicating greater impairment) in the 70+ than 70− age group at 1 year follow-up (table 4). At M12, according to the ZBPI, 70+ patients more frequently presented with HZ-related sleep disorder and impaired enjoyment of life (p=0.05). Despite pain treatment, the percentage of patients reporting ‘relief of pain during the past 24 h’ decreased progressively in 70+ patients; it was significantly lower in the 70+ than 70− age group at M6 and M12 (χ2 test: p=0.06 at M6 and p=0.04 at M12, respectively; table 4).

Table 4.

Zoster Brief Pain Inventory (ZBPI) scores at D0 (all patients) and at M3, M6 and M12 (patients with PHN) per age group (70− or 70+)

| D0 |

M3 |

M6 |

M12 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZBPI scores | 70− | 70+ | 70− | 70+ | 70− | 70+ | 70− | 70+ |

| Interference score | ||||||||

| N | 559 | 457 | 34 | 47 | 24 | 27 | 13 | 15 |

| Mean | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.9 |

| p<0.01 | ||||||||

| Impact of pain on general activity | ||||||||

| N | 572 | 483 | 34 | 48 | 24 | 32 | 14 | 17 |

| Mean | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 4.1 |

| Impact of pain on walking | ||||||||

| N | 570 | 480 | 34 | 49 | 24 | 32 | 14 | 17 |

| Mean | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 3.1 |

| Impact of pain on sleep | ||||||||

| N | 571 | 488 | 34 | 49 | 24 | 31 | 14 | 18 |

| Mean | 4.1 | 4.5 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 4.4 |

| p<0.01 | ||||||||

| Impact of pain on enjoyment of life | ||||||||

| N | 572 | 484 | 34 | 49 | 24 | 32 | 14 | 18 |

| Mean | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Percentage of patients reporting pain relief during the past 24 h | ||||||||

| Mean | 64.7 | 52.1 | 73.6 | 46.6 | 72.0 | 28.8 | ||

| (SD) | (37.1) | (25.4) | (31.3) | (31.3) | (25.9) | (24.7) | ||

| p=0.06 | p=0.04 | |||||||

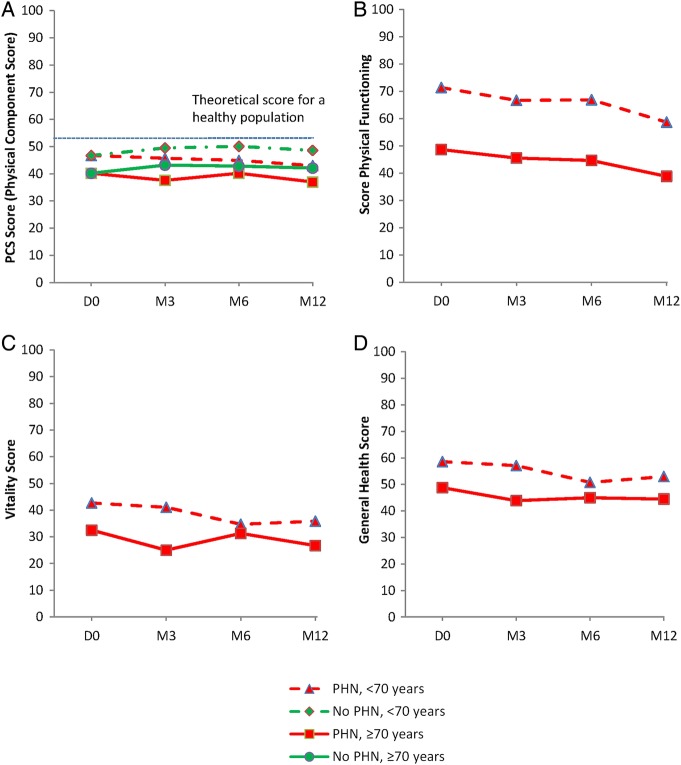

SF12 Physical Component Score (PCS) (figure 2A), Physical Functioning (figure 2B), Vitality (figure 2C) and General Health (figure 2D) scores were systematically and significantly lower in patients with pain (acute at D0, and PHN at M3, M6 and M12) in the 70+ than 70− age group (p<0.01), and the gap between the two age groups was greater at M12 and M6 than at D0. Age per se had a significant effect (p<0.001) on these parameters.

Figure 2.

SF12 quality of life at inclusion and follow-up in patients with or without post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN). Comparison between 70− and 70+ patients: (A) Physical Component Score (PCS) (p<0.01 at all time points); (B) Physical Functioning (p<0.01 at all time points); (C) Vitality (p<0.01 at all time points); (D) General Health (p<0.01 at all time points). SF12, Short-Form health survey.

ZBPI interference score was particularly high (3.5±2.3 and 3.6±2.7) and the SF12 PCS component particularly low (37.9±10.0 and 34.2±8.9) in very old patients (80–85 and 85+ age groups, respectively). Physical functioning and vitality scores were both lower in the 85+ age group: 26.6±33.6 and 25.4±23.0, respectively, and significantly different from 70− patients’ scores (p<0.001).

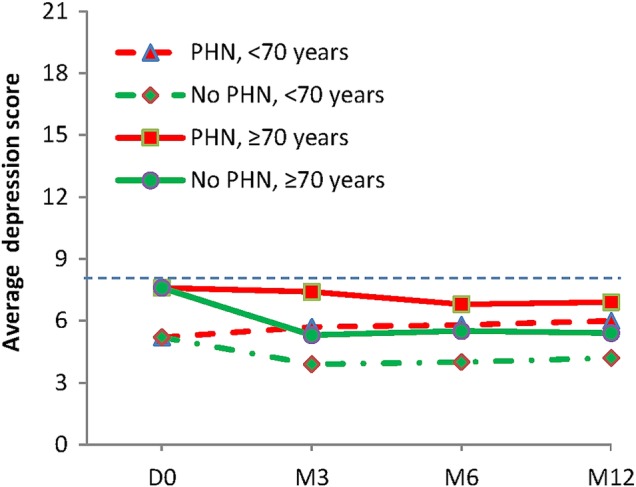

The HADS (figure 3) depression score was higher in the 70+ than 70− age group at D0 (7.6±4.6 vs 5.2±4.3 p=0.01) and at all other time points (p=0.001). The mean HADS depression score and HADS anxiety scores were close to without reaching the depression and anxiety thresholds (ie, 8).

Figure 3.

Depression scores (HADS) at inclusion and follow-up. HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Univariate analyses showed that predictive factors for reduced SF12 PCS comprised: HZ-related pain at M3 (p<0.001), age≥70 years (p<0.001), initial ZBPI interference score >5 (p=0.015) and comorbidity at diagnosis (D0) (p<0.001).

Discussion

This study highlights the deleterious impact of HZ and PHN on overall functional status in elderly (≥70 years of age) compared to younger patients (50–70 years of age). The study, which was a post hoc analysis of the ARIZONA study,12 showed that, 1 year after HZ, persistent HZ-related pain was associated with marked impairment of quality of life, especially on the physical component of the SF12 and mood (HADS depression score), indicating a concomitant physical and psychological impact of chronic pain on patients’ health status, particularly in the most elderly. Both persistent pain and age as well as the presence of comorbidities before onset of HZ were predictive of this functional decline. Results also showed increased analgesics consumption in 70+ patients, amplified in 80+ patients.

Chronic conditions disproportionately affect older persons, who often combine several pathologies and have complex health problems.13 In this study, at inclusion, 77.1% of the older vs 49.1% of the younger patients had comorbidities, and some of these pathologies may induce pain and discomfort. Comorbidities had a deleterious impact on SF12-PCS scores at M6 (p<0.001) and can be a predictive factor of a marked deterioration of this criterion. When elderly persons develop HZ infection, the acute painful episode is in itself a debilitating, painful and tiring experience, inducing a diminished quality of life. The higher ZBPI interference scores in the elderly show that this pathology is more distressing in older than younger persons and, as shown in this study, this score is a predictive factor for PHN at 3 months. Persistence of pain and presence of neuropathic characteristics often sign a longer disease course than expected, in some cases lasting months or even years. Traumatic personal life events were present in 23% of patients of all ages, and a strong association with occurrence of HZ in the preceding 6 months has been shown in the literature.23

Polypharmacy is very common in older persons17 18 24 and increases the risk of drug-related adverse effects and interactions.25–28 HZ requires the prescription of additional drugs, consisting of analgesics and sedatives with a central mechanism of action and potential adverse effects. In the year following HZ, the rate of prescription remained higher in elderly than in younger patients. In patients who develop HZ-related pain, prescription rates were steady, as all patients were maintained on analgesics. There was a significantly greater anticonvulsant prescription (mostly gabapentin or pregabalin) in older persons. Anticonvulsant prescription to relieve neuropathic pain rose from 9.7% at D0 to 33.3% at M6, and 25.0% at M12; at M6, two-thirds of patients aged ≥85 years received one anticonvulsant drug. This prescription is in line with guidelines for neuropathic pain treatment in elderly patients.29 The American Geriatrics Society strongly recommends that tertiary tricyclic antidepressants should be avoided in older patients, because of the risk of anticholinergic, cardiac and cognitive adverse effects.30 31 Anticonvulsants, despite associated adverse effects, including dizziness, somnolence, gait disorder, falls, weight gain and swelling of the hands and feet,18 32 should be prescribed at reduced doses, especially in patients with renal impairment. The increased consumption of analgesics, hypnotics/sedatives and anxiolytics in the oldest patients in this study may reflect an increasingly palliative attitude in pharmacological treatment of the most elderly persons.33 It may also be that pain and the resulting psychological burden tend to increase in old age: in this study, while pain relief remained constant during 1-year of follow-up in 70− patients, it was reduced by half in 70+ patients despite unchanged treatment. Impairment of inhibitory descending pain pathways due to age and PHN-induced central sensitisation may also play a role in this resistance to pain relief.34 Analgesics and coanalgesics prescribed for HZ and PHN have an impact on several domains of cognition, including vigilance, decision-making and semantic memory,35 and patients suffer from pain, as well as from associated depression, anxiety, sleep disorder and a marked diminution of quality of life, with impaired ZBPI, SF12 and HADS scores.36 37

The negative impact of HZ and PHN on daily life activities in 70+ patients was seen throughout follow-up and was more pronounced than in younger patients. ZBPI interference score, ZBPI general activity, work, sleep and enjoyment of life scores and SF12 scores were greatly affected, especially in the most elderly. Despite taking more antidepressants at inclusion and more anticonvulsants for PHN treatment, older patients had more depressive symptoms, a poorer QoL and poor sleep, and experienced less pain relief from drugs. This risk of deleterious progression of HZ towards PHN was probably not known or was at least underestimated by patients, who may have expected rapid recovery and good immediate efficacy of pain treatment. This lesser pain relief in the oldest and most vulnerable persons highlights the difficulty of managing HZ and PHN in this age group, where the balance of pain relief, drug-related adverse events and patient expectations will need to be assessed more precisely in future studies. Elderly persons should be informed that prevention of HZ should significantly limit the functional decline due to acute and chronic (PHN) HZ-related pain.38

Prophylaxis of HZ and PHN by vaccination is today possible. A one-dose live attenuated zoster vaccine is currently licensed for use in immunocompetent adults aged over 50 years. This vaccine has demonstrated both in clinical trials and in real-life conditions (effectiveness studies) its ability to reduce the incidence and severity of HZ and the incidence of PHN.8 39 Its safety profile, assessed with 30 million doses distributed all over the world, is satisfactory. Vaccine recommendations vary according to countries, taking into considerations the epidemiology and burden of the disease and vaccine characteristics. In France, for example,40 the vaccine is recommended for the vaccination of adults aged 65–74 years with a one-dose vaccination regimen. During the first year after the inclusion of the vaccine in the vaccination calendar, individuals aged 75–79 years can also be vaccinated as part of a catch-up phase. Vaccination of patients aged over 80 years has not been evaluated from a health economics point of view, in the absence of sufficient data concerning the efficacy and duration of protection conferred by vaccination in this age group.40 In the future, a two-dose adjuvanted subunit vaccine could be used to prevent HZ and its consequences. The efficacy of this subunit vaccine under development has been recently proven.41 Taking into account the composition of this inactivated vaccine candidate, it would be especially interesting for immunocompromised patients.

This post hoc analysis of the ARIZONA study involved some limitations: telephone contact for follow-up, absence of data on cognitive and communication profile, and absence of stratification on ethnic groups. On the other hand, this was a large-scale study implemented in primary care. Moreover, few patients were lost to follow-up and information was collected for most patients for all items. Another possible limitation was that the data were collected 6 years ago; however, to the best of our knowledge, no change has occurred since in the management of HZ in the ‘real world’.

Conclusion

In elderly patients with age-related comorbid diseases and polypharmacy, occurrence of HZ and progression to PHN causes an additional burden on top of pharmacological treatment and comorbid adverse events. Quality of life is greatly affected and activities of daily life are diminished in patients who may already have health problems to cope with in everyday life. Information on HZ, which is a very common infectious disease, and its possible complications should be provided more widely to the elderly population. HZ prophylaxis by vaccination is today a valuable option that could prevent the added burdens of HZ, long-standing persistent PHN, extra medications and impaired quality of life in an immunocompetent but frail elderly population. Moreover, neuropathic pain medications must be prescribed cautiously in such patients, considering their adverse effects, and the additional iatrogenic risk related to the frequency of comorbidities and related treatments that they could present. This specific point has to be taken into account and supports the rationale of zoster and PHN prevention by vaccination.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Iain Mc Gill for his help in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: GP, GG, JG, MP, KB and DB contributed substantially to the conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The logistics of the study was supported by Sanofi Pasteur MSD (Lyon, France).

Competing interests: The ARIZONA study was supported in part by Sanofi-Pasteur MSD, Lyon, France. The use of the DN4 questionnaire is subject to fees for their developers, including DB.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: French Ethics Committee France.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sigurdur H, Gunnar P, Sigurdur G et al. Prevalence of postherpetic neuralgia after a first episode of herpes zoster: prospective study with long term follow up. BMJ 2000;321:794–6. 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee VK, Simpkins L. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in the elderly. Geriatr Nurs 2000;21:132–5; quiz 136. 10.1067/mgn.2000.108260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dworkin RH, Schmader KE. The epidemiology and natural history of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. 2nd edn Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001:39–64. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmader K, Gnann JW, Watson CP. The epidemiological, clinical, and pathological rationale for the herpes zoster vaccine. J Infect Dis 2008;197(Suppl 2):S207–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen JI. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1766–7. 10.1056/NEJMc1310369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinchinat S, Cebrián-Cuenca A, Bricout H et al. Similar herpes zoster incidence across Europe: results from a systematic literature review. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:170 10.1186/1471-2334-13-170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yenikomshian MA, Guignard AP, Haguinet F et al. The epidemiology of herpes zoster and its complications in medicare cancer patients. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:106 10.1186/s12879-015-0810-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng HF, Smith N, Harpaz R et al. Herpes zoster vaccine in older adults and the risk of subsequent herpes zoster disease. JAMA 2011;305:160–6. 10.1001/jama.2010.1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langan SM, Smeeth L, Margolis DJ et al. Herpes zoster vaccine effectiveness against incident herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in an older US population: a cohort study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001420 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choo PW, Galil K, Donahue JG et al. Risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1217–24. 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440320117011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coen PG, Scott F, Leedham-Green M et al. Predicting and preventing post-herpetic neuralgia: are current risk factors useful in clinical practice? Eur J Pain 2006;10:695–700. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouhassira D, Chassany O, Gaillat J et al. Patient perspective on herpes zoster and its complications: an observational prospective study in patients aged over 50 years in general practice. Pain. 2012;153:342–9. 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schäfer VS, Kermani TA, Crowson CS et al. Incidence of herpes zoster in patients with giant cell arteritis: a population-based cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:2104–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duracinsky M, Paccalin M, Gavazzi G et al. ARIZONA study: is the risk of post-herpetic neuralgia and its burden increased in the most elderly patients? BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:529 10.1186/1471-2334-14-529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milte R, Crotty M. Musculoskeletal health, frailty and functional decline. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2014;28:395–410. 10.1016/j.berh.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weston C, Weston J. Applying the Beers and STOPP criteria to care of the Critically Ill older adult. Crit Care Nurs Q 2015;38:231–6. 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickering G. Analgesic use in the older person. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:207–12. 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32835242d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickering G, Lussier D. Pharmacology of pain in the elderly. In: Lussier D, Beaulieu P, eds. Pharmacology of pain. USA: IASP Press, 2010:547–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drolet M, Brisson M, Schmader KE et al. The impact of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia on health-related quality of life: a prospective study. CMAJ 2010;182:1731–6. 10.1503/cmaj.091711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coplan PM, Schmader K, Nikas A et al. Development of a measure of the burden of pain due to herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia for prevention trials: adaptation of the brief pain inventory. J Pain 2004;5:344–56. 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lasserre A, Blaizeau F, Gorwood P et al. Herpes zoster: family history and psychological stress-case-control study. J Clin Virol 2012;55:153–7. 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickering G, Capriz-Ribière F. Neuropathic pain in the elderly. Psych Neuropsychiatr Vieil 2008;6:107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lackner TE. Strategies for optimizing antiepileptic drug therapy in elderly people. Pharmacotherapy 2002;22:329–64. 10.1592/phco.22.5.329.33192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beard K. Adverse reactions as a cause of hospital admission in the aged. Drugs Aging. 1992;2:356–67. 10.2165/00002512-199202040-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Routledge PA, O'Mahony MS, Woodhouse KW. Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004;57:121–6. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01875.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atkin PA, Veitch PC, Veitch EM, Ogle SJ. The epidemiology of serious adverse drug reactions among the elderly. Drugs Aging 1999;14:141–52. 10.2165/00002512-199914020-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent pain in older persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatrics Soc 2009;57:1331–46. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reisner L. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Pain 2011;12(Suppl 1):S21–9. 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gloth FM., III Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons: focus on opioids and nonopioids. J Pain 2011;12(Suppl 1):S14–20. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickering G. Antiepileptics for post-herpetic neuralgia in the elderly: current and future prospects. Drugs Aging 2014;31:653–60. 10.1007/s40266-014-0202-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wastesson JW, Parker MG, Fastbom J et al. Drug use in centenarians compared with nonagenarians and octogenarians in Sweden: a nationwide register-based study. Age Ageing 2012;41:218–24. 10.1093/ageing/afr144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickering G, Pereira B, Dufour E et al. Impaired modulation of pain in patients with post-herpetic neuralgia. Pain Res Manag 2014;19:e19–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pickering G, Pereira B, Clère F et al. Cognitive function in patients with PHN. Pain Pract 2014;14:E1–7. 10.1111/papr.12079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pickering G, Leplege A. Herpes zoster pain, postherpetic neuralgia, and quality of life in the elderly. Pain Pract 2011;11:397–402. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lydick E, Epstein RS, Himmelberger D et al. Herpes zoster and quality of life: a self-limited disease with severe impact. Neurology 1995;45:S52–3. 10.1212/WNL.45.12_Suppl_8.S52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmader KE, Johnson GR, Saddier P et al. , Shingles Prevention Study Group. Effect of a zoster vaccine on herpes zoster-related interference with functional status and health-related quality-of-life measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Assoc Soc 2010;58:1634–41. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03021.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR et al. , Shingles Prevention Study Group. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2271–84. 10.1056/NEJMoa051016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haut Conseil de la santé publique. Avis relatif à la vaccination des adultes contre le zona avec le vaccin Zostavax®. 25-October-2013. http://www.hcsp.fr/Explore.cgi/AvisRapports (accessed 3 Dec 2015).

- 41.Lal H, Cunningham AL, Godeaux O et al. , ZOE-50 Study Group. Efficacy of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2087–96. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]