Abstract

Objective

To report outcomes of patients with localised prostate cancer (PCa) managed with active surveillance (AS) in a standard clinical setting.

Design

Single-centre, prospective, observational study.

Setting

Non-academic, average-size hospital in Switzerland.

Participants

Prospective, observational study at a non-academic, average-size hospital in Switzerland. Inclusion and progression criteria meet general recommendations. 157 patients at a median age of 67 (61–70) years were included from December 1999 to March 2012. Follow-up (FU) ended June 2013.

Results

Median FU was 48 (30–84) months. Overall confirmed reclassification rate was 20% (32/157). 20 men underwent radical prostatectomy with 1 recurrence, 11 had radiation therapy with 2 prostate-specific antigen relapses, and 1 required primary hormone ablation with a fatal outcome. Kaplan-Meier estimates for those remaining in the study showed an overall survival of 92%, cancer-specific survival of 99% and reclassification rate of 41%. Dropout rate was 36% and occurred at a median of 48 (21–81) months after inclusion. 68 (43%) men are still under AS.

Conclusions

Careful administration of AS can and will yield excellent results in long-term management of PCa, and also helps physicians and patients alike to balance quality of life and mortality. Our data revealed significant dropout from FU. Patient non-compliance can be a relevant problem in AS.

Keywords: active surveillance, localized, prostate cancer, clinical setting, dropout, compliance

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study reports 13 years of experience in active surveillance of prostate cancer in an average clinical setting.

The prospective design of the study allows for monitor of compliance and dropout.

Owing to the single-centre setting at a mid-size hospital, the number of patients is relatively low.

Problems concerning patient compliance were not considered at the beginning of this study. Therefore, no historical psychological data were obtained.

Introduction

Active surveillance (AS) is a treatment option for small-volume, low-grade prostate cancer (PCa). Overall survival (OS) is remarkably high, while at the same time overtreatment is reduced and the attendant loss of quality of life (QoL) is minimised.1

Despite the evolution of AS over the past 20 years, the widespread adoption of AS as a primary management tool for low-risk PCa has been limited.2–4 Recently, Copperberg and Caroll reported that a wide application of AS for low-risk PCa in the USA started to increase from 2010; between 1990 and 2009, the use of AS remained low at 6–14% and then increased to 40% from 2010 to 2013.5 Data presented at the American Urological Association 2015 Annual Meeting highlighted the recent growth in the use of AS in both US and European practices, prompting some experts to announce, “The era of active surveillance has arrived”.6 This recent upswing in the application of AS is to be lauded. However, aside from the improved health outcomes among the male population, is there anything else that can be gained from the experiences of AS?

Incautious application or oversimplification of the technique may risk changing the balance from overtreatment to undertreatment, and result in a concomitant fear among patients. Differences in practice between the USA and Europe will imply that trans-Atlantic generalisation of study data and conclusions are not always valid. Moreover, data and findings in AS have been presented almost exclusively from large institutional studies, or multi-institutional, multiregional or international registry studies such as the Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance (PRIAS) study—an exception being data published from the cancer of the prostate strategic urologic research endeavor (CaPSURE) PCa registry reporting on patients with PCa managed at 47 primarily community-based clinical sites in the USA.7 8 Furthermore, a large diversity of practice across Europe has recently been reported, showing that urologists who are not participating in a clinical trial appear to apply less rigorous criteria for both inclusion and follow-up (FU).9

In 1999, we began a prospective AS clinical trial in our average-sized clinic with the intention of assessing the outcome of patients with PCa managed with AS. We hoped this study would provide insight into a real-world application of AS in a smaller non-academic hospital in the European setting. Our study has now been running for over 13 years and we, hereby, present results from this long-term longitudinal study in the context of outcomes reported from large studies. Importantly, our data also offer surprising insights into AS type treatment strategies and highlight risk areas that may not always be identifiable in a retrospective manner.

Patients and methods

From December 1999 to March 2012, we consecutively enrolled all men who were eligible (AS criteria) and had willingly chosen AS. All treatment options were equally offered with detailed explanations. Eligible men had an estimated life expectancy of more than 10 years. The ethics commission of the state of Aargau approved the use of the study data. Patients gave written informed consent, after which they were followed within a routine clinical setting at our department. The main informed consent form did not change over the study period. However, a supplementary sheet with detailed information concerning FU schedule, inclusion and exclusion criteria underwent changes in 2005, as listed below.

Criteria and FU schedule

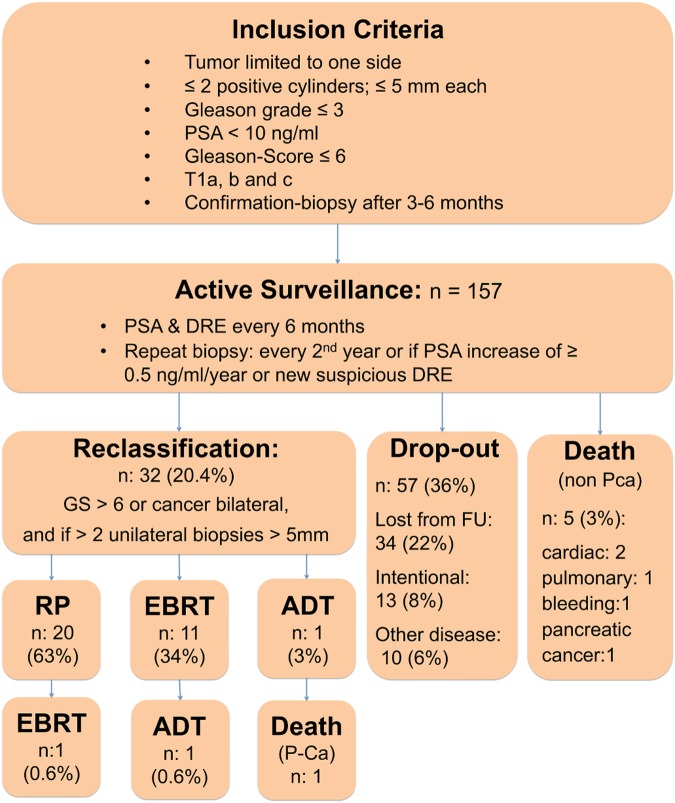

The following inclusion criteria were used: tumour limited to one lobe of the prostate with no more than two positive cylinders not exceeding 5 mm tumour length each, and no Gleason grade >3, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) <10 ng/mL. Before the Gleason score (GS) was modified, a score of 5 was the uppermost limit. This rose to 6 with the introduction of the new modified GS in 2005. Furthermore, we included patients with T1a and b cancers. Confirmation biopsy was performed within 3–6 months for transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-diagnosed and transurethral resection of the prostate (TUR-P)-diagnosed patients showing the same or lesser form of the disease. We performed standardised TRUS-guided prostate biopsy with five randomly distributed cores from each side of the prostate. Patients were then followed every 6 months with PSA testing and digital rectal examination (DRE). Indications for repeat biopsy were a PSA increase of ≥0.5 ng/mL/year or a new suspicious lesion at DRE. We scheduled rebiopsy initially every year and after 2005, every second year for those without PSA increase and normal DRE (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of active surveillance cohort. ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; DRE, digital rectal examination; EBRT, external beam radiotherapy; FU, follow-up; GS, Gleason score; PCa, prostate cancer; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; RP, radical prostatectomy.

Reclassification was defined as the need for definitive treatment. We recommended treatment with curative intent (radical prostatectomy (RP) or external beam radiotherapy (EBRT)) if the biopsy revealed a GS >6 or cancer in both lobes, and if more than two unilateral biopsies exceeded a tumour length of more than 5 mm per core.

If the patient did not show up for the scheduled FU, he received a minimum of two new appointments. Subsequent attempts included phone contact and personal letters. If this failed, clinical FU data were obtained through the general practitioner, if available. To eliminate potential FU bias, we only included patients who were in the cohort for more than 1 year (to March 2012) and used a June 2013 cut-off for data analysis.

Clinical outcome measures

The primary outcome of the study was the rate of reclassification (defined as need for definitive treatment). Secondary outcomes were OS and dropout from FU for any reason. Values with a non-normal distribution are reported as medians and IQRs (25–75%). For survival analyses, we generated Kaplan-Meier estimates. We used the χ2 test to evaluate whether the risk of progression was different for T1c- (biopsy) or T1a and b- (TUR-P) diagnosed cancer. FU and survival were calculated from the date of inclusion to the date of last evaluation (true FU) on 30 June 2013 for all patients who remained in FU. We used Graph Pad Prism V.6.04 for all analyses. A p value of <0.05 was used as the level of statistical significance.

Results

From December 1999 to March 2012, 157 men at a median age of 67 (61–70) years were included in the AS protocol (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variable | Median (range) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 67 (61–70) |

| PSA, ng/mL | 4.3 (2.8–6.4) |

| GS ≤6 | 154 (98) |

| GS 7 | 3 (1.9) |

| T1a–b | 61 (38.9) |

| T1c | 96 (61.1) |

| FU, months | 48 (30–84) |

FU, follow-up; GS,Gleason score; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Median FU was 48 (30–84) months and median PSA was 4.3 (2.8–6.4) before cancer diagnosis. Of the 157 patients, 96 were included after TRUS-guided biopsy and 61 after TUR-P. GS at inclusion was 6 (minimum 5, maximum 7). Three men with GS 7 voluntarily enrolled for observation throughout the study, using all other AS criteria.

Compliance

Confirmation biopsy was carried out in 127 (81%) men with a positive cancer identification rate of 31%. Thirty men (19%) did not undergo confirmation biopsy. Of the 61 patients enrolled after TUR-P, only 40 men underwent confirmation biopsy (66%) with a positive cancer identification rate of 23% (9 of 40 men). Strict compliance would have generated 1891 PSA values and 512 prostate biopsies; however, 1142 PSA values were measured and 325 biopsies were performed; however, 39.7% of PSA values and 36.5% of biopsies were missing, thus showing inconsistent patient compliance.

Reclassification

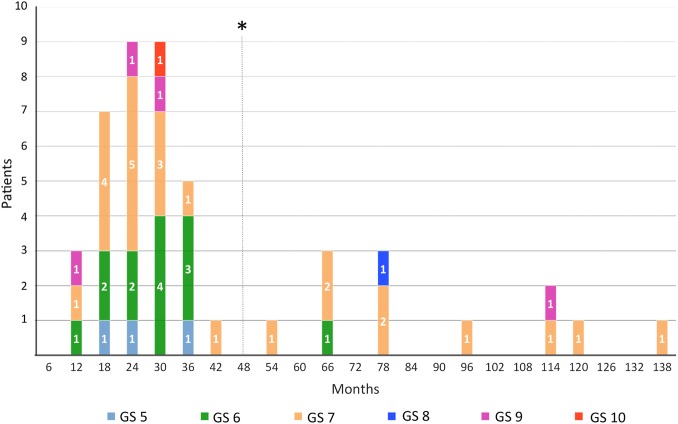

Of the total 157 men, 32 (20%) were observed to be reclassified and needed secondary intervention. Six men (10%) from the primarily TUR-P diagnosed and 26 (27%) from the TRUS diagnosed group (χ2 p=0.009) progressed. Median time to reclassification for both groups (TUR-P and TRUS) was 24 (14–36) months and to treatment 26 (19–35) months. For reclassification defined by volume, the criterion for receiving definitive treatment for more than two cancerous GS-5 biopsy cores were met in three patients, and GS-6 biopsy cores were found in eight patients. For GS reclassification: for 21 men, increasing GS was crucial. Sixteen men had a GS of 7, one man had a GS of 8, three men had a GS of 9 and one man had a GS of 10 (figure 2 and table 2).

Figure 2.

Reclassification events with regard to follow-up time and Gleason score (GS; *median time of dropout).

Table 2.

Reclassification by Gleason score (GS) upgrade and tumour volume

| Gleason score reclassification | n |

|---|---|

| GS 7 | 16 |

| GS 8 | 1 |

| GS 9 | 3 |

| GS 10 | 1 |

| Total | 21 |

| Volume reclassification | n |

| >2 cores | 11 |

Definitive treatment

Twenty (63%) men who were reclassified (total 32 men) underwent RP and 11 (34%) had EBRT. One individual with a GS 10 cancer required direct androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and subsequently died (figure 1).

Of 20 men undergoing, nine (45%) had a GS of 6, five (25%) had a GS of 7a, three (15%) had a GS of 7b, one (5%) had GS 8 and two (10%) had GS 9. All Gleason 6 tumours were multifocal, 1.3 cm median diameter in five men and 0.7 cm diameter in four men. FU after RP was 52 (12–76) months and 21(15–51) months after EBRT. Second-line therapy was needed only in one man after RP (received EBRT) and in one after EBRT (received ADT). All these patients remain stable. Five patients (3%) died of non-disease-related causes: cardiac disease (2), pulmonary disease (1), non-cancer-related bleeding (1) and pancreatic cancer (1).

Dropout

A total of 57 men (36% of all enrolments) dropped out of the study or were lost to FU. Median time to dropout was 48 months (21–81) with a median age of 69 (65–75) years. Eighteen men (11.5% of all enrolments) refused further urological scheduled FU, and four men (7.5% of all enrolments) stated a disease of higher priority (table 3 vide infra).

Table 3.

Reasons for dropout

| Reason for dropout | N | Percentage of dropout | Percentage of cohort |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intentional | 18 | 31.6 | 11.5 |

| At other urologist | 1 | 1.8 | 0.6 |

| Moved abroad | 3 | 5.2 | 1.9 |

| Disease of higher priority | 4 | 7 | 2.5 |

| No data | 31 | 54.4 | 19.5 |

| Total | 57 | 100 | 36 |

Thirty-one men (19.5% of total enrolments) were considered lost to FU after either no response or no further information was forthcoming >12 months following the last scheduled appointment.

Outcomes

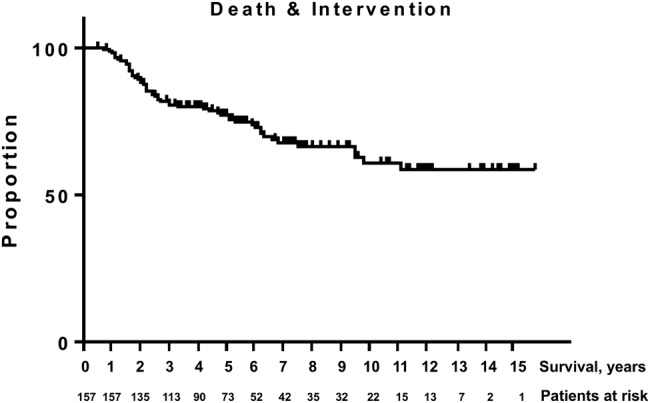

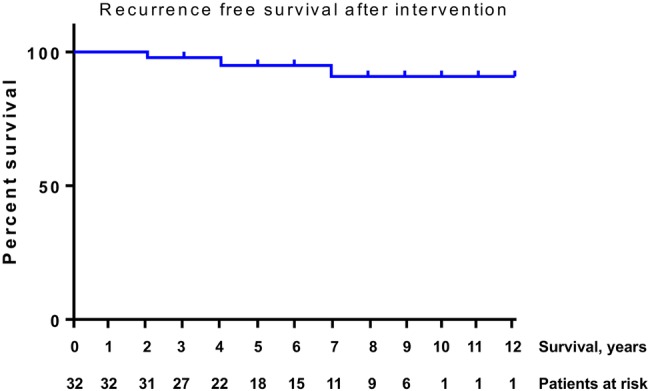

Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed an estimated OS of 92%, cancer-specific survival (CSS) of 99% and reclassification rate of 41% for all patients remaining on FU or with recorded death on study (figure 3). Progression-free survival after treatment was 90% (figure 4). Sixty-eight men (43%) of the initial cohort still remain under AS, with a median FU of 42 (20–66) months.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of death and intervention (combined; cancer-specific survival: 99%, overall survival: 92%, reclassification: 41%).

Figure 4.

Recurrence-free survival after treatment was 90%.

Discussion

This study represents a large long-term prospectively analysed cohort of patients with PCa managed primarily with AS in an average-sized, non-academic, single-centre setting. CSS and OS rates were good and comparable to published AS cohorts.10–14

Reclassification and definitive treatment

Reclassification leading to definitive treatment by RP, RT or ADT was identified in 20% of our cohort. Twenty per cent of our cohort showed Gleason grade progression leading to definitive treatment (RP, RT, ADT) after a median FU time of 2 years. This is again comparable to other large cohorts that show an average progression rate of 25% (11–33%) after a median FU of 2.44 (1.3–3.5) years.1 In our cohort, patients included after TUR-P were less likely to progress (10% vs 27%, p=0.009). This is also comparable to other large trials.15 Hence, our findings support the implementation of incidental tumours in AS, as it is recommended in the recently published S3-Guidelines of the German Society of Urology.16

Dropout and compliance

Only few reports have looked at compliance problems in AS.17 18 The PRIAS study group recently reported that some men do not comply with the FU schedule and even refuse recommended active treatment.18 Their compliance rate for yearly repeat biopsies decreased over time, resulting in only 33% of men undergoing standard biopsy after 10 years. Similar experiences in our cohort led to the reduction from yearly biopsies to a biannual biopsy schedule from 2005.

Dropout is a feature present in most clinical trials. The total dropout rate of 36% we observed over the course of this study is considerably higher than that in other published studies reports. Dropout of 10% was found in a selected population of patients highly motivated for AS.11 Three other studies report loss to FU rates of 6–10% vs 22% loss to FU observed in our cohort.11 12 14

Our reclassification rate is calculated using the number of reclassification events definitively identified. Given that we have no progression data for 36% of our cohort, if we were to assign all patients who dropped out to the reclassification population, the rate of reclassification would be uncharacteristically and improbably high at 56.7%. Median time to dropout (all dropouts) was 48 months. In our cohort, 22% (n=7) of all progression events took place after 48 months (4.5% intention-to-treat; 7% of patients remaining in the study). This suggests that some patients probably end FU before they enter progression and as prostate biopsies revealed several aggressive tumours even after 48 months, these patients could conceivably develop a non-curable disease.

Why do patients dropout?

As a considerable unknown in our results and as FU is the essential core treatment modality, we explored potential reasons for this inexplicably high dropout rate (table 3). We started our AS programme in 1999 when AS was not yet an established treatment option, and were fully aware of the potential risk. Therefore, we focused on extended patient information. Nonetheless, we observe considerable failure to appear at the scheduled FU. Most of our patients informed us that the biopsies were bothersome and that the appointments seemed too numerous. Given that our technique and FU protocol were in line with international norms, we feel that this does not account for the higher dropout rate. Other explanations may be downplay or avoidance of the situation or a lack of understanding of the complex ongoing process despite considerable efforts in patient education.

Switzerland has a highly advanced medical and social welfare system with mandatory health insurance for all residents, so lack of access to healthcare is considered to play no role in dropout. We searched our patient records for clues that might otherwise explain the high dropout rate. In our region, there are many expatriate residents who return to their homeland after retirement. However, patients lost to FU were almost exclusively Swiss citizens, and unlikely to be migratory.

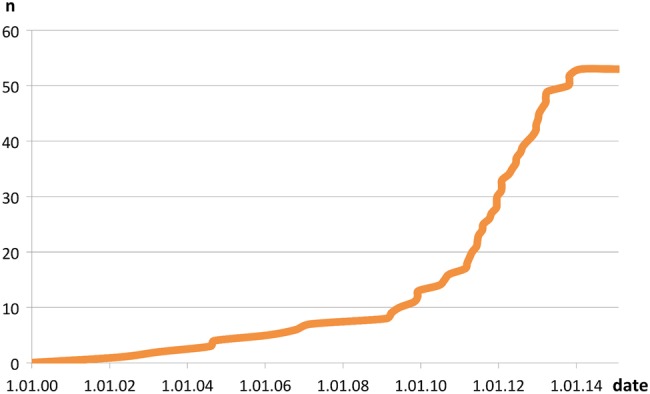

Further analysis of our data revealed that there were no correlations between dropout and time on study, or dropout and age, but the dropout rate increased dramatically after 2009 (figure 5). This could not be attributed to a sudden rise in enrolments, the rate of which remained relatively stable throughout the study. We also examined our personnel database to see if the sharp increase in dropout rate could be attributed to a staff change that might have been perceived negatively by patients. No such correlations were found.

Figure 5.

Time points of dropout events.

Although statistically difficult to prove (and maybe speculative), it is possible that the publication of two very large cohort studies in NEJM in 2009 and the subsequent media storm surrounding the value of PCa screening may well have had a very real effect on the public perception of PSA testing and by proxy, on the attitudes of men on AS programmes like ours.19 20

Using Google trends, we investigated the incidence and interest of the terms ‘PSA’ and ‘prostate’ in the local media in our region. We see a regular occurrence of news reports relating to PCa and PSA testing beginning in 2009. The most prominent and influential Swiss television health broadcast ran a series of 10 reports on PCa and PSA testing beginning in 2009.21 Many of these reports were highly critical of PSA testing in general and cited the 2009 NEJM publications, and these can still be accessed online. We believe that the effects of publically available emotive mass media reporting of complex statistical medical results to a lay audience can have a powerful effect on the mood and psyche of patients.

Psychological aspects of AS

The psychological suitability of a patient to be managed with AS can affect the acceptance and success of AS. We found that cancer fear was not a prevalent factor in our study experience. Very few of our patients favoured definitive treatment if the alternative was AS. Several studies report that fear of treatment-related side effects is a strong motivator for choosing AS.22–24 At the same time it has been demonstrated that during FU anxiety is very low and therefore, seemingly not a problem in AS.25 Surprisingly, the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) showed that men with an unsuspicious biopsy but suspicious PSA were significantly less likely to return for the scheduled FU compared with men with normal PSA.26 Hence, it might be presumed that the combination of cancer fearlessness, lack of symptoms and fear of treatment-related side effects could lead to carelessness in some men. Some might eventually regard the disease as trivial and become non-compliant.

Limitations of this study

Our data span 13 years and our number of patients (157) is relatively low. A longer time sequence would provide more validity to the outcome of very low-risk PCa. However, our median FU of 48 months is comparable to that of other long-term studies.10–14 27–29

Problems concerning patient compliance were not considered at the beginning of this study; therefore, no historical psychological data were obtained, and retrospective analysis of separate data in a prospective study could be misleading.

We acknowledge that our study represents a single-centre experience with a limited number of patients, which certainly does not allow for generalisability of our results. However, many of the reasons given for the dropout are not specific to our hospital or region, but could in fact take place in many countries worldwide.

Conclusion

Careful administration of AS can and will yield excellent results in long-term management of PCa, and also help physicians and patients alike to balance QoL and mortality. Our data revealed significant dropout from FU. Patient non-compliance can be a relevant problem in AS. Compared with many other cancer treatment options, AS embodies the unique and specific potential problems of dropout and should not be underestimated. Further, we postulate that a patient's mood and understanding of the AS concept and utility can be strongly affected by environmental factors. We suggest that a comprehensive psychological assessment be included as part of determining the suitability of any given patient for AS, not only on initiation but also at each FU. Moreover, psychological assessment should, if possible, include measures to help predict compliance.

Acknowledgments

Randall Watson, PhD; Patricia von Bergen; Jan Bass, MD, Rachel Groebli-Bolleter, MD; Scherwin Talimi, MD; Markus Zahner, MD.

Footnotes

Contributors: LJH and KL were involved in planning, execution, analysis, writing, editing; DD was involved in planning, execution, analysis; all authors of this research paper have directly participated in the planning, execution and analysis of this study, and have read and approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The ethics commission of the state of Aargau, Switzerland, approved the use of the study data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Dall'Era MA, Albertsen PC, Bangma C et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol 2012;62:976–83. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chodak GW, Thisted RA, Gerber GS et al. Results of conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 1994;330:242–8. 10.1056/NEJM199401273300403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albertsen P, Fryback D, Storer B et al. Long-term survival among men with conservatively treated localized prostate cancer. JAMA 1995;274:626–31. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530080042039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choo R, Klotz L, Danjoux C et al. Feasibility study: watchful waiting for localized low to intermediate grade prostate carcinoma with selective delayed intervention based on prostate specific antigen, histological and/or clinical progression. J Urol 2002;167:1664–9. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65174-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR. Trends in management for patients with localized prostate cancer, 1990–2013. JAMA 2015;314:80–2. 10.1001/jama.2015.6036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulcahy N. ‘Era of Active Surveillance Has Arrived’ in Prostate Cancer. Medscape Medical News, Conference News. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/844809?nlid=81403_1004&src=wnl_edit_medp_urol&uac=224577PK&spon=15.

- 7.Xia J, Trock BJ, Cooperberg MR et al. Prostate cancer mortality following active surveillance versus immediate radical prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:5471–8. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bul M, Zhu X, Valdagni R et al. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer worldwide: the PRIAS study. Eur Urol 2013;63:597–603. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azmi A, Dillon RA, Borghesi S et al. Active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer: diversity of practice across Europe. Ir J Med Sci 2015;184:305–11. 10.1007/s11845-014-1104-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klotz L, Vesprini D, Sethukavalan P et al. Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:272–7. 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tosoian JJ, Trock BJ, Landis P et al. Active surveillance program for prostate cancer: an update of the Johns Hopkins experience. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2185–90. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.8112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Bergh RC, Roemeling S, Roobol MJ et al. Outcomes of men with screen-detected prostate cancer eligible for active surveillance who were managed expectantly. Eur Urol 2009;55:1–8. 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khatami A, Aus G, Damber JE et al. PSA doubling time predicts the outcome after active surveillance in screening-detected prostate cancer: results from the European randomized study of screening for prostate cancer, Sweden section. Int J Cancer 2007;120:170–4. 10.1002/ijc.22161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soloway MS, Soloway CT, Williams S et al. Active surveillance; a reasonable management alternative for patients with prostate cancer: the Miami experience. BJU Int 2008;101:165–9. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07190.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.BJU International. doi: 10.1111/bju.13308. Herden J, Wille S, Weissbach L. (2015), Active surveillance in localized prostate cancer: comparison of incidental tumours (T1a/b) and tumours diagnosed by core needle biopsy (T1c/T2a): results from the HAROW study. 2015. doi: 10.1111/bju.13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Interdisziplinäre Leitlinie der Qualität S3 zur früherkennung, Diagnose und Therapie der verschiedenen Stadien des Prostatakarzinoms, Langversion 3.1, AWMF Registernummer: 034/022. http://leitlinienprogrammonkologie.de/Leitlinien7.0.html.

- 17.Hefermehl LJ, Disteldorf D, Talimi S et al. MP45-02 13 years of experience in active surveillance for prostate cancer. J Urol 2014;191:e459–60. 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.1199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bokhorst LP, Alberts AR, Rannikko A et al. Compliance rates with the Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance (PRIAS) protocol and disease reclassification in noncompliers. Eur Urol 2015;68:814–21. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1320–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1310–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fokus by mediscope; Prostatakrebs: Jeder achte PSA-Test ist falsch positiv; Sprechzimmer ch. 2010;11.01.2010 http://www.sprechzimmer.ch/sprechzimmer/Fokus/Prostatakrebs/Aktuell/Prostatakrebs_Jeder_achte_PSA_Test_ist_falsch_positiv.php.

- 22.Sidana A, Hernandez DJ, Feng Z et al. Treatment decision-making for localized prostate cancer: what younger men choose and why. Prostate 2012;72:58–64. 10.1002/pros.21406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anandadas CN, Clarke NW, Davidson SE et al. Early prostate cancer—which treatment do men prefer and why? BJU Int 2011;107:1762–8. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorin MA, Soloway CT, Eldefrawy A et al. Factors that influence patient enrollment in active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer. Urology 2011;77:588–91. 10.1016/j.urology.2010.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davison BJ, Goldenberg SL. Patient acceptance of active surveillance as a treatment option for low-risk prostate cancer. BJU Int 2011;108:1787–93. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10200.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford ME, Havstad SL, Demers R et al. Effects of false-positive prostate cancer screening results on subsequent prostate cancer screening behavior. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:190–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van As NJ, Norman AR, Thomas K et al. Predicting the probability of deferred radical treatment for localised prostate cancer managed by active surveillance. Eur Urol 2008;54:1297–305. 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roemeling S, Roobol MJ, de Vries SH et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancers detected in three subsequent rounds of a screening trial: characteristics, PSA doubling times, and outcome. Eur Urol 2007;51:1244–51. 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klotz L. Active surveillance: the Canadian experience with an ‘inclusive approach’. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2012;2012:234–41. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]