Abstract

Objective

This systematic review identifies, describes and appraises the literature describing the utilisation of helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) in the early medical response to major incidents.

Setting

Early prehospital phase of a major incident.

Design

Systematic literature review performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, Cinahl, Bibsys Ask, Norart, Svemed and UpToDate were searched using phrases that combined HEMS and ‘major incidents’ to identify when and how HEMS was utilised. The identified studies were subjected to data extraction and appraisal.

Results

The database search identified 4948 articles. Based on the title and abstract, the full text of 96 articles was obtained; of these, 37 articles were included in the review, and an additional five were identified by searching the reference lists of the 37 articles. HEMS was used to transport medical and rescue personnel to the incident and to transport patients to the hospital, especially when the infrastructure was damaged. Insufficient air traffic control, weather conditions, inadequate landing sites and failing communication were described as challenging in some incidents.

Conclusions

HEMS was used mainly for patient treatment and to transport patients, personnel and equipment in the early medical management of major incidents, but the optimal utilisation of this specialised resource remains unclear. This review identified operational areas with improvement potential. A lack of systematic indexing, heterogeneous data reporting and weak methodological design, complicated the identification and comparison of incidents, and more systematic reporting is needed.

Trial registration number

CRD42013004473.

Keywords: Air ambulances, Helicopter emergency medical services, Major incidents, Disasters, Mass casualty incidents

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a systematic literature review that follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The protocol was published before conducting the study to avoid data-driven decisions; deviations from the protocol are noted in the article.

Only literature in English and in Scandinavian languages is included.

Introduction

Major incidents remain a major global health challenge. In 2013, natural-triggered disasters killed more than 20 000 people, created almost 100 million victims and caused enormous economic damage worldwide.1 These numbers are only for natural disasters and do not take into account other types of major incidents. Major incidents are characterised by the need for an extraordinary medical response. They are heterogeneous by nature and their unexpectedness remains a challenge for emergency medical services (EMS). Fundamental for an effective major incident response is a robust and resilient EMS system.2 These systems can provide rapid access to advanced major incident management to improve patient outcome3 and optimise resource allocation as demand often exceeds capacity.4

Helicopters are obvious resources in major incident management through their capacity to bring specialised teams and equipment to incident scenes. They can also transport patients, provide search and rescue services, and perform overhead surveillance. When a site is remote or difficult to access, helicopters may be the only way to transport personnel, equipment and patients in and out of it.5–9 Following the first organised use of helicopters for military medevac during the Korean War,10 the use of helicopters for civilian patient transportation was introduced in the USA in the early 1970s.11 It was later integrated as helicopter EMS (HEMS) in most high-income countries.12–14 Although HEMS is embedded in most emergency response plans, the optimal use of this limited resource in the early medical management of major incidents remains unclear.

We aimed to systematically identify, describe and appraise the literature that describes the utilisation of HEMS in the early medical response to major incidents, to better address common challenges and to facilitate future research.

Methods

Study identification

The protocol was published prior to conducting the literature search15 and registered in PROSPERO (CRD42013004473). A comprehensive literature search was performed to identify all relevant articles available as of 19 March 2015. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, Cinahl, Bibsys Ask, Norart, Svemed and UpToDate. An additional search was performed in PubMed in order to retrieve articles that had not yet been entered into medline. The search was designed using Medical Subject Headings and related terms as keywords. This search was then adapted for use in the other databases (see online supplementary additional file I). In the absence of universally accepted nomenclature, literature that defined their incident as a major incident or disaster was included.

Study eligibility and selection

Inclusion criteria:

Articles that describe the use of HEMS in the early medical management of a major incident.

Exclusion criteria:

Articles in languages other than English and Scandinavian

Articles without abstracts

Book chapters, conference abstracts, letters to the editor and editorials

Deviations from the protocol on inclusion and exclusion criteria.15

Inclusion of commentaries

- Exclusion of literature where:

- Only fixed-wing aircraft were used

- Helicopters without dedicated medical capacity were used

- Incidents were considered to be part of military conflicts

- HEMS was used in the later recovery phase of the response.

The reason for the inclusion of commentaries was that these did not provide less relevant information than case reports. Exclusion criteria were adjusted to better target civilian medical helicopter response to major incidents in the acute phase.

Search findings

All studies were collected in an Endnote bibliographic database (2011; Thomson Reuters, USA). One author (ASJ) scanned the titles and abstracts, and excluded articles that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria. Full-text versions of the remaining articles were obtained and divided among pairs of authors (ie, ASJ and MR, SF and SJMS) for further screening, using the criteria listed above. Excluded articles were listed with the reason(s) for exclusion. If there was any uncertainty about whether a study should be included, there was a discussion until a consensus was reached among all of the authors. The reference lists of the studies that were included initially were examined individually to identify the additional relevant literature.

Data extraction and appraisal

ASJ appraised the quality of the included studies and extracted predefined data from the included articles into an Excel spreadsheet (2010; Microsoft, USA). Data extraction included the demography of incident area and characteristics regarding HEMS, major incident, incident response and patient characteristics. The data extraction variables were pilot-tested on four randomly selected articles before the protocol was published.15 The appraisal items were selected by the authors, and aimed to describe the internal and external validity of the included studies. All data extraction and appraisal results were agreed on by another co-author.

Results

Literature search

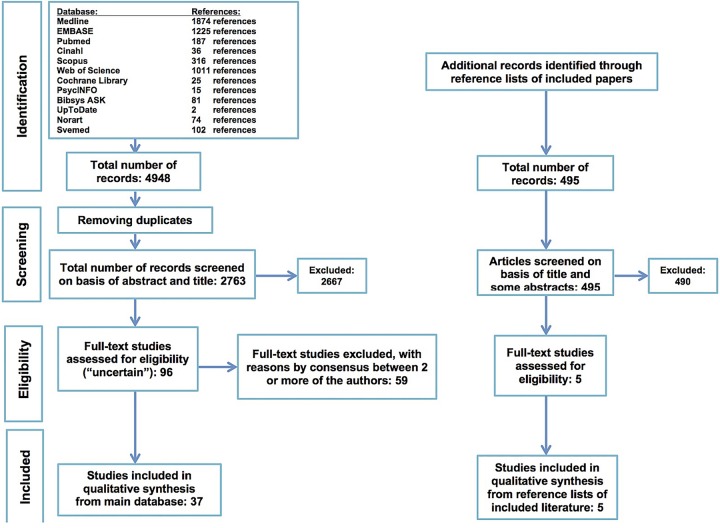

The search identified 4948 records (2763 after duplicates were removed), and the full-text versions of 96 articles were obtained. Of these, 37 articles6–9 16–48 were included in the study, and an additional 549–53 were identified by searching through the reference lists of the 37 articles. Thus, the review included a total of 42 articles (table 1), with 59 articles excluded for various reasons (see online supplementary additional file II). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram (figure 1) shows the inclusion and exclusion of articles in the different phases of this review.54

Table 1.

Study methods and use of HEMS

| Method | Described use of HEMS | |

|---|---|---|

| Afzali et al16 | Prospective observational study | Brought extra equipment for advanced life support. HEMS doctor was Medical Incident Officer in three major incidents |

| Almersjø et al49 | Case report | Performed search and rescue and secondary transfers |

| Ammons et al17 | Case report | Evacuated the most severely injured patients to hospitals and brought extra equipment to the scene |

| Assa et al7 | Case report | Brought extra personnel and equipment to the scene. Air-medical crews assisted ground units in triage and treatment. Transportation of casualties from the remotely located scene to trauma centres. Allowed distribution of patients between various centres in the region |

| Bland18 | Case report | Command, triage, treatment and transport. Author was Forward Medical Incident Officer at Kings Cross scene |

| Bovender and Carey19 | Case report | Used for more than 200 helicopter sorties from flooded hospital |

| Brandsjø et al50 | Case report | Rescued main proportion of survivors, because nearby ships could not perform sea rescue |

| Brandstrom et al20 | Case report | Search and Rescue |

| Buerk et al21 | Case report, design not clearly described | Evacuated severely injured patients. Caused disruption of radio communication and destroyed an aid station. The possibility of collision was a concern |

| Buhrer and Tilney22 | Case report | Patient transport with advanced life support and a secondary transfer to a burn centre |

| Carlascio et al23 | Case report, design not clearly described | Secondary transfers and rescued one patient. Brought extra crew and blood products |

| Cassuto and Tarnow24 | Case report, design not clearly described | Secondary transfers from urban fire disaster |

| Cocanour et al25 | Case report, describing same type of incident as Bovender and Nates | Evacuated patients from a flooded hospital. Used for longer distance transport |

| Eckstein and Cowen26 | Case report | Not clearly described |

| Felix Jr 27 | Summarizes HEMS in USA in the early1970s with a major incident case report | Flew equipment to two damaged hospitals and transferred patients to other hospitals |

| Franklin et al28 | Case report | Patient transport from flooded areas to hospital and brought health personnel to places where they were needed |

| Furukawa28 | Case report | Transported personnel to the remote site of an airplane crash and airlifted survivors and dead from the scene |

| Iselius29 | Case report describing the same incident as Oestern | Evacuation of injured passengers from railway accident. Brought extra crew and equipment to the site |

| Jacobs et al30 | Review of seven major incidents in one HEMS service describing the same inci- dents as Stohler | Used for evacuation and transport of the most critically injured patients to trauma centres. Distributed them to different centres, so not to overwhelm the closest one |

| Lavery and Horan31 | Case report | Primary and secondary transport of injured patients |

| Lavon et al32 | Two case reports | Brought extra personnel, equipment and command team to the local hospital. Participated in secondary transfer with advanced trauma life support to larger trauma centre |

| Leiba et al33 | Case report describing the same incident as Lavon | Brought extra personnel and blood products to the closest hospital and evacuated patients |

| Leiba et al34 | Case report describing the same incident as Assa. The DISAST-CIR methodology of reporting also used by Schwartz | Primary transport of injured to different hospitals ensuring that the closest hospital did not reach surge capacity |

| Lockey et al35 | Case report describing the same incident as Bland | Deployed staff and equipment to the scenes and staff from home to the hospitals. Allowed rapid deployment in difficult traffic conditions |

| Lyon and Sanders36 | Commentary of a case report | Brought pre-hospital doctors to the scene for medical incident command and advanced interventions. Transported the patients directly to specialist paediatric trauma centres |

| Malik et al37 | Observational study of scoring systems in a major incident in remote area | Transported personnel to the incident. Secondary transport of priority I patients to trauma centre |

| Martchenke et al38 | Case report, interviewing all participating HEMS members involved | Triage, treatment and transport of patients from earthquake |

| Martin51 | Case report | Helicopter and personnel present at event. Tasks not specified |

| Matsumoto et al39 | Case report | Mainly used for patient transportation and evacuation. Also transported food, water and generators to destroyed hospitals |

| Nates40 | Case report and review of literature. Describing same type of incident as Bovender and Cocanour | Transport of patients from damaged hospital, vital in evacuation because of damaged roads |

| Nia et al53 | Case report and survey of survivor's opinions about health response | Evacuated injured from the earthquake zone and brought resources and equipment to affected area |

| Nicholas and Oberheide52 | Case report describing the same incident as Ammons | Transport from primary to secondary health care facility. Brought supplies to scene |

| Nocera and Dalton41 | Two case reports | Transport of experienced crew to the scene. Performed advanced life-saving procedures in one of the incidents |

| Oestern et al42 | Case report describing the same incident as Iselius | Transported patients to more remote hospitals |

| Pokorny43 | Case report | Evacuation of victims in flooded area, otherwise not specified. |

| Romundstad et al44 | Case report | Arriving HEMS doctor was appointed Medical Incident Commander and organized medical resources in teams. Transported some of the patients to more remote hospitals |

| Schwartz and Bar-Dayan45 | Case report presented in DISAST-CIR met-hodology for uniform presentation. Leiba 2009 used same methodology | Patient transport of the most seriously injured patients |

| Sollid et al46 | Case report | Flew out extra personnel and stretchers. Triaged and treated patients acted as medical incident commander and transported the most severely injured from one of the incident sites |

| Spano et al9 | Case report | Brought personnel and equipment to site and evacuated the patients when weather allowed |

| Stohler et al8 | Retrospective review of four major incidents. Same incidents as Jacobs | The responses included bringing extra personnel and equipment to scene, triage, medical treatment, air surveillance and transport |

| Urquieta and Varon47 | Case report | Triage and transport of severely injured victims |

| Yi-Szu et al48 | Case report, analysing patterns and outcomes of patients with chest injuries | Secondary transport of patients from field hospitals in earthquake zone. |

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Data extraction

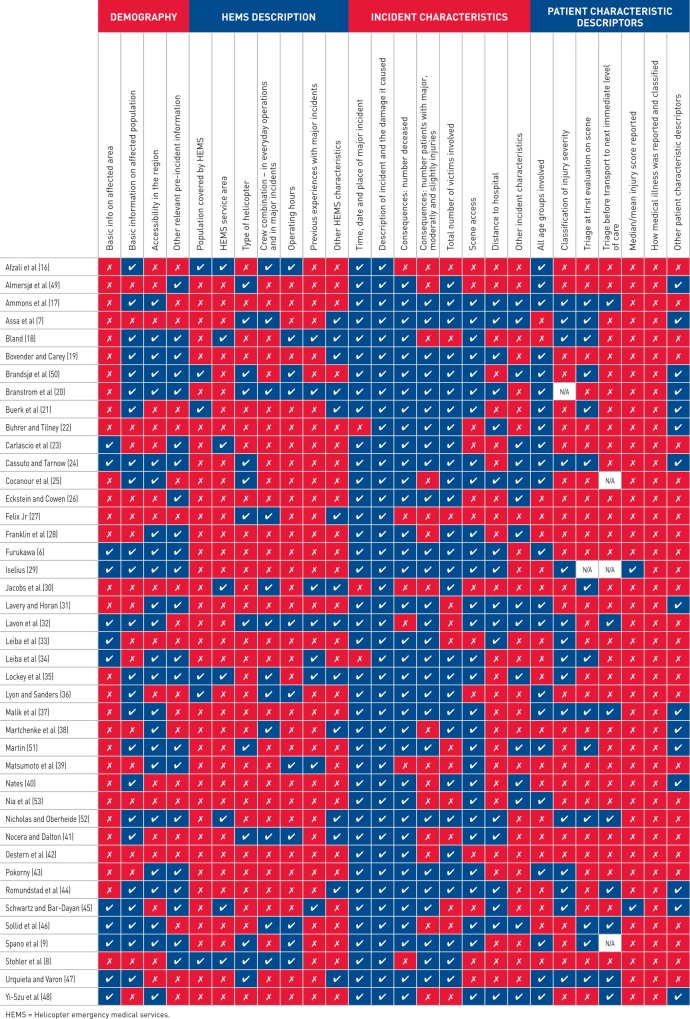

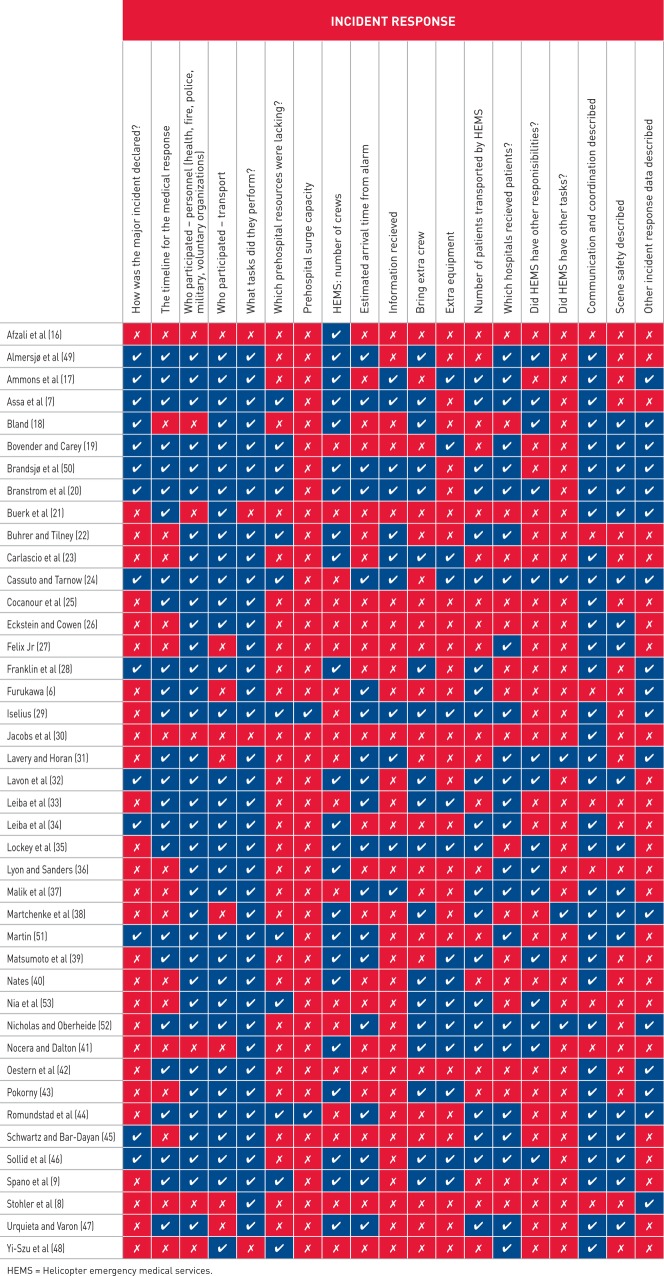

None of the included articles contained all of the items on the data extraction list (figure 2). Basic information about the affected area was described in 12 articles (29%), information about the affected population in 24 (57%) and scene access in 29 articles (69%). Most papers described the characteristics of the incident. A timeline for the incident response was present in 25 articles (59%) and a description of personnel in 35 (83%) articles. In 12 (29%) of the articles, there was a lack of resources, prehospital surge capacity was reported in 2 (5%), and the response time was documented in 19 articles (45%). Communications and coordination were described in 34 articles (81%), and were in most cases failing. Scene safety was reported to be an issue in 18 reports (43%), and this was related to issues such as inadequate air traffic control, active shooters, inadequate landing sites and bad weather. HEMS tasks included patient evacuation and transport from scene as well as transport of supplies, personnel and equipment to the scene. The literature also described HEMS being used for secondary transport, treatment, leadership and on-scene triage. In addition, HEMS was in some incidents utilised for search and rescue, and for air surveillance (table 1).

Figure 2.

Data extraction.

Figure 2.

Continued

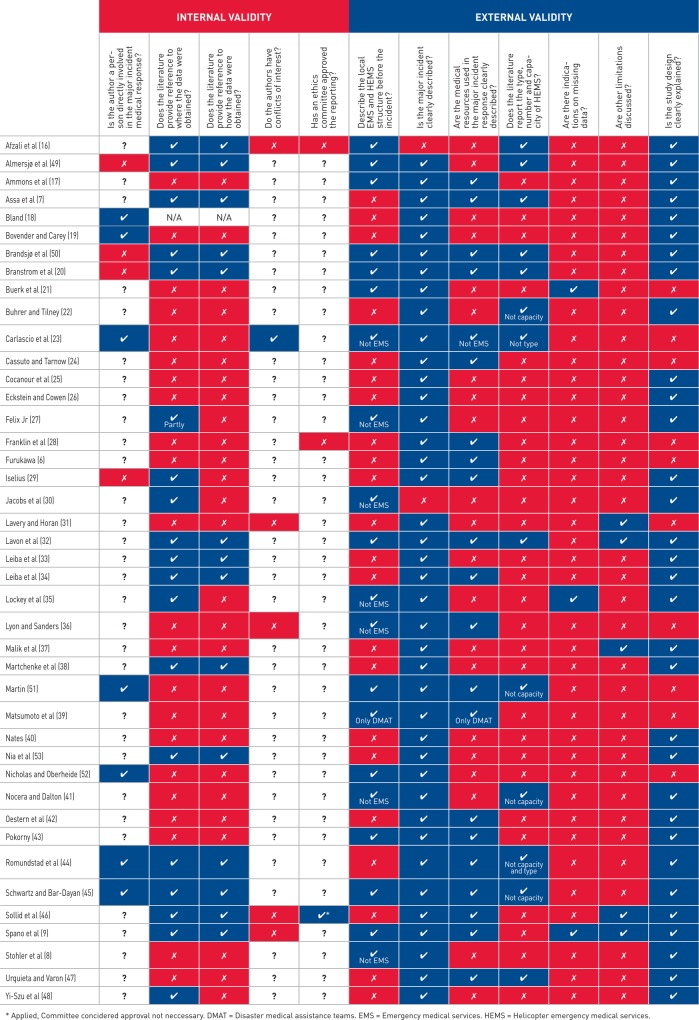

Appraisal

We sought to identify data items related to internal and external validity. Of the included articles, 19 (45%) contained references to where the data were obtained. We found 5 articles (12%) that reported no conflicts of interests and 1 (2%) that reported a conflict of interests. No articles reported they had ethical approval, although 1 (2%) stated that such approval was not needed. The description of both the HEMS and EMS structure before the incident was described in 12 (29%), whereas 7 articles (17%) described HEMS alone. The incident itself was clearly described in 40 articles (95%). Study limitations were discussed in 5 (12%), and the study design was described in 32 articles (76%). The quality appraisal findings are shown in figure 3. The study methodology was as follows: Of the 42 included studies, 37 (88%) were case reports, 2 (5%) observational studies, 2 (5%) reviews and 1 (2%) was a summary of the use of HEMS combined with a case report (table 1).

Figure 3.

Appraisal.

Discussion

This systematic literature review found little or no systematic reporting of the utilisation of HEMS in the early medical management of major incidents. HEMS were most often reported to be used in patient evacuation and transport from the scene, and in transport of supplies and personnel to the incident scene (table 1). Data relevant to depict internal and external validity, such as reference to data source and handling of missing data, were lacking (figure 3). Further, the heterogeneity of the literature and the overall weak methodological design made it difficult to evaluate the contribution of HEMS to the management of major incidents.

The included incidents had various logistical and geographical challenges. In the 7/7 London terrorist bombings in 2005, a helicopter was used to deploy staff and equipment to urban scenes when road access was difficult.35 Use of a helicopter also allowed the deployment of staff from home at a time when public transportation was inaccessible in the city. In the 22/7 Utøya terrorist shootings in 2011, additional medical personnel were brought to the scene, which this time was a rural area with overloaded provincial roads.46 Other studies described how HEMS facilitated the transport of victims to the hospital, especially when the scene of the incident was difficult to access.49 25 HEMS also helped in secondary transfers of patients with particular needs, such as transporting patients to dedicated burns units.24 Although scene safety remains a foremost priority in major incident management, this was discussed in less than half of the studies. The inability to fly due to bad weather8 and the lack of designated landing sites19 31 47 were described as operational hazards. Further, HEMS involvement in major incident management often involved multiple aircraft operating in uncontrolled air space, indicating insufficient air traffic control.21 23 27 38 46 Future improvements in aviation traffic awareness systems, navigation and communication may mitigate the aviation risks. However, the emphasis should be on implementing procedures for multiple aircraft operations in uncontrolled air space. Crew training may also reduce the risks associated with confined area landings and bad weather flight operations.

The heterogeneous nature of major incidents is reflected by the lack of a common nomenclature.55 Several definitions of a major incident have been proposed that differ slightly from each other.56–58 To avoid excluding relevant articles, literature that defined their incident as a major incident or disaster was included. Our findings emphasise that a universally accepted definition of major incident is needed to facilitate comparative studies and to improve the accuracy of database indexing.

Our appraisal found that the majority of the included articles provided detailed descriptions of the incidents but that there was a tendency towards inadequate descriptions of the everyday HEMS system. The lack of baseline data made it difficult to evaluate the deployment and utilisation of extraordinary resources during major incidents. The methodological designs were generally weak and dominated by retrospective observational case reports. This is not surprising considering the difficulties in planning and executing prospective studies on major incidents. With an established template of standardised variables, a prospective study design can, however, be established to collect data from major incidents. If similar data are collected from major incident exercises in similar systems, a case–control design can even be applied to future studies. Such studies can be further strengthened by including other data sources such as focus group interviews from involved personnel in the sense of method triangulation.59 60 We also found that some incidents were described by several reports, indicating possible skewedness in the literature regarding high-profile incidents. As with all unstructured reporting, establishing a denominator for HEMS involvement proved difficult, again highlighting that future research should build on systematically collected data with uniform variable definitions to allow better comparisons.61

Limitations

The authors selected items for use in data extraction and appraisal that they assumed were relevant. However, these items do not represent a reference standard, since such a standard does not exist, to our knowledge.

Many major incidents occur in non-English-speaking countries; accordingly, it is a weakness that only articles in English and the Nordic languages were included. However, the included articles described incidents on different continents, which improve the generalisability of the findings. Further, we may have failed to identify some relevant studies, since articles without abstracts were not included, and a single author performed the initial screening.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review identified, described and appraised the literature on the utilisation of HEMS in the early medical management of major incidents. Heterogeneous data reporting complicated our efforts to identify and evaluate the overall utilisation of HEMS in such incidents. To address such shortcomings, systematic uniform reporting of HEMS in major incidents is called for.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marie Isachsen, Ullevål University Hospital Library, Oslo, Norway, who designed and conducted the literature search.

Footnotes

Contributors: ASJ and MR conceived the study. ASJ, MR, SJMS and SF took part in study design, data analysis and writing of the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: All of the authors are employed by the Norwegian Air Ambulance Foundation, which played no part in the study design, data collection, data analysis, or manuscript preparation processes.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Guha-Sapir D, Hoyois P, Below R. Annual disaster statistical review 2013: the numbers and trends. Brussels: Cred, 2014. http://www.cred.be/sites/default/files/ADSR_2013.pdf (accessed 3 Sep 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasser S,Varghese M, Kellermann A et al. . Prehospital trauma care systems. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aylwin CJ, König TC, Brennan NW et al. . Reduction in critical mortality in urban mass casualty incidents: analysis of triage, surge, and resource use after the London bombings on July 7, 2005. Lancet 2006;368:2219–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69896-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasser S. Field triage in disasters. Prehosp Emerg Care 2006;10:322–3. 10.1080/10903120600728722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler DP, Anwar I, Willett K. Is it the H or the EMS in HEMS that has an impact on trauma patient mortality? A systematic review of the evidence. Emerg Med J 2010;27:692–701. 10.1136/emj.2009.087486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furukawa K, Kubo K. Accident of Japan Air Lines Flight 123 Boeing 747. Aircraft and dealing with the disaster. J Med Leg Droit Med 1994;37:157–66. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assa A, Landau DA, Berenboim E et al. . Role of air-medical evacuation in mass-casualty incidents–a train collision experience. Prehosp Disaster Med 2009;24:271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stohler SA, Jacobs LM, Gabram SGA. Roles of a helicopter emergency medical service in mass casualty incidents. J Air Med Transp 1991;10:7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spano SJ, Campagne D, Stroh G et al. . A lightning multiple casualty incident in Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks. Wilderness Environ Med 2015;26:43–53. 10.1016/j.wem.2014.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driscoll RS. New York chapter history of military medicine award. U.S. Army medical helicopters in the Korean war. Mil Med 2001;166:290–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs LM, Bennett B. A critical care helicopter system in trauma. J Natl Med Assoc 1989;8:1157–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor C, Jan S, Curtis K et al. . The cost-effectiveness of physician staffed Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) transport to a major trauma centre in NSW, Australia. Injury 2012;43:1843–9. 10.1016/j.injury.2012.07.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salimi J, Khaji A, Khashayar P et al. . Helicopter emergency medical system in a region lacking trauma coordination (experience from Tehran). Emerg Med J 2009;26:361–4. 10.1136/emj.2008.060012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krüger AJ, Skogvoll E, Castrén M et al. . Scandinavian pre-hospital physician-manned Emergency Medical Services—Same concept across borders? Resuscitation 2010;81:427–33. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnsen AS, Fattah S, Sollid SJM et al. . Impact of helicopter emergency medical services in major incidents: systematic literature review. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003335 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afzali M, Hesselfeldt R, Steinmetz J et al. . A helicopter emergency medical service May allow faster access to highly specialised care. Dan M J 2013;60:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ammons MA, Moore EE, Pons PT et al. . The role of a regional trauma system in the management of a mass disaster: an analysis of the Keystone, Colorado, chairlift accident. J Trauma 1988;28:1469–71. 10.1097/00005373-198810000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bland SA. HEMS training and the 7th July 2005: a personal perspective. J R Nav Med Serv 2006;92:130–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bovender JO Jr, Carey B. A week we Don't want to forget: lessons learned from Tulane. Front Health Serv Manage 2006;23:3–12.; discussion 25-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandstrøm H, Sedig K, Lundalv J. Kamedo 77. MS Sleipners förlisning. Socialstyrelsen 2003:1–96. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/10743/2003-123-7_20031238.pdf (accessed 1 Oct 2015) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Buerk CA, Batdorf JW, Cammack KV et al. . MGM Grand Hotel Fire: lessons learned from a major disaster. Arch Surg 1982;117:641–4. 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380290087015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buhrer S, Tilney P. Blast lung injury in a 20-year-old man after a home explosion. Air Med J 2012;31:10–12. 10.1016/j.amj.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlascio DR, McSharry MC, LeJeune CJ et al. . Air medical response to the 1990 Will County, Illinois, Tornado. J Air Med Transp 1991;10:7–16. 10.1016/S1046-9095(05)80002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassuto J, Tarnow P. The discotheque fire in Gothenburg 1998. Burns 2003;29:405–16. 10.1016/S0305-4179(03)00074-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocanour CS, Allen SJ, Mazabob J et al. . Lessons learned from the evacuation of an Urban teaching hospital. Arch Surg 2002;137:1141–5. 10.1001/archsurg.137.10.1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckstein M, Cowen AR. Scene safety in the face of automatic weapons fire: a new dilemma for ems? Prehosp Emerg Care 1998;2:117–22. 10.1080/10903129808958854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felix WR., Jr Metropolitan aeromedical service: state of the art. J Trauma 1976;16:873–81. 10.1097/00005373-197611000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franklin JA, Wiese W, Meredith JT et al. . Hurricane Floyd. N C Med J 2000;61:384–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iselius L. Kamedo—79. Tågolyckan i Tyskland 1998. Socialstyrelsen 2004:1–24. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/10414/2004-123-3_20041233.pdf (accessed 1 Oct 2015).

- 30.Jacobs LM, Gabram SGA, Stohler SA. The integration of a helicopter emergency medical service in a mass casualty response system. Prehosp Disaster Med 1991;6:451–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavery GG, Horan E. Clinical review: Communication and logistics in the response to the 1998 terrorist bombing in Omagh, Northern Ireland. Crit Care 2005;9:401–8. 10.1186/cc3502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavon O, Hershko D, Barenboim E. Large-scale airmedical transport from a peripheral hospital to level-1 trauma centres after remote mass-casualty incidents in Israel. Prehosp Disaster Med 2010;24:549–55. 10.1017/S1049023X00007500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leiba A, Blumenfeld A, Hourvitz A et al. . Lessons learned from cross-border medical response to the terrorist bombings in Tabba and Ras-el-Satan, Egypt, on 07 October 2004. Prehosp Disaster Med 2005;20:253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leiba A, Schwartz D, Eran T et al. . DISAST-CIR: disastrous incidents systematic analysis through components, interactions and results: application to a large-scale train accident. J Emerg Med 2009;37:46–50. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lockey DJ, MacKenzie R, Redhead J et al. . London bombings July 2005: the immediate pre-hospital medical response. Resuscitation 2005;66:ix–xii. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyon RM, Sanders J. The Swiss bus accident on 13 March 2012: lessons for pre-hospital care. Crit Care 2012;16:138 10.1186/cc11370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik ZU, Pervez M, Safdar A et al. . Triage and management of mass casualties in a train accident. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2004;14:108–11. doi:02.2004/JCPSP.108111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martchenke J, Lynch T, Pointer J et al. . Aeromedical helicopter use following the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Aviat Space Environ Med 1995:359–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsumoto H, Motomura T, Hara Y et al. . Lessons learned from the aeromedical disaster relief activities following the great east Japan earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med 2013;28:166–9. 10.1017/S1049023X12001835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nates JL. Combined external and internal hospital disaster: impact and response in a Houston trauma center intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2004;32:686–90. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000114995.14120.6D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nocera A, Dalton M. Disaster alert! The role of physician-staffed helicopter emergency medical services. Med J Aust 1994;161:689–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oestern HJ, Huels B, Quirini W et al. . Facts about the disaster at Eschede. J Orthop Trauma 2000;14:287–90. 10.1097/00005131-200005000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pokorny JR. Flood disaster in the Czech Republic in July, 1997—operations of the emergency medical service. Prehosp Disaster Med 1999;14:32–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romundstad L, Sundnes KO, Pillgram-Larsen J et al. . Challenges of major incident management when excess resources are allocated: experiences from a mass casualty incident after roof collapse of a military command center. Prehosp Disaster Med 2004;19:179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz D, Bar-Dayan Y. Injury patterns in clashes between citizens and security forces during forced evacuation. Emerg Med J 2008;25:695–8. 10.1136/emj.2007.055996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sollid SJ, Rimstad R, Rehn M et al. . Oslo government district bombing and Utøya island shooting July 22, 2011: the immediate prehospital emergency medical service response. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2012;20:3. http://www.sjtrem.com/content/20/1/3 (accessed 4 Sep 2015). 10.1186/1757-7241-20-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urquieta E, Varon J. Mexico City's Petroleos Mexicanos explosion: disaster management and air medical transport. Air Med J 2015;33:309–13. 10.1016/j.amj.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yi-Szu W, Chung-Ping H, Tzu-Chieh L et al. . Chest injuries transferred to trauma centres after the 1999 Taiwan earthquake. Am J Emerg Med 2000;18:825–7. 10.1053/ajem.2000.18132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Almersjø O, Ask E, Brandsjo K et al. . Branden på passagerarfärjan Scandinavian Star den 7 april 1990. Socialstyrelsen, 1998:1–51. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/12697/1997-3-15.pdf (accessed 01 Oct 2015)

- 50.Brandsjø K, Haggmark T, Kulling P et al. . Kamedo- 68. Estoniakatastrofen. Socialstyrelsen. SoS- rapport 1997:15 2010:1–172.

- 51.Martin TE. The Ramstein Airshow Disaster. J R Army Med Corps 1990;136:19–26. 10.1136/jramc-136-01-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicholas RA, Oberheide JE. EMS response to a ski lift disaster in the Colorado mountains. J Trauma 1988;28:672–5. 10.1097/00005373-198805000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nia MS, Nafissi N, Moharamzad Y. Survey of Bam earthquake survivors’ opinions on medical and health systems services. Prehosp Disaster Med 2008;23:263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:1–28. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nocera A. Australian major incident nomenclature: it may be a ‘disaster’ but in an ‘emergency’ it is just a mess. ANZ J Surg 2001;71:162–6. 10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Advanced Life Support Group. Major incident medical management and support, the practical approach. Plymouth, UK: BMJ Publishing Group, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lennquist S. Medical response to major incidents and disasters. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fattah S, Rehn M, Lockey D et al. . A consensus based template for reporting of pre-hospital major incident medical management. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2014;22:5 10.1186/1757-7241-22-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jick TD. Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: triangulation in action. Adm Sci Q 1979;24:602–11. 10.2307/2392366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merry AF, Davies JM, Maltby JR. Qualitative research in health care. Br J Anaesth 2000;84:552–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hardy S. Major incidents in England. BMJ 2015;350:1712 10.1136/bmj.h1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]