Abstract

Objective

To compare the efficacy and safety of a concentrated formulation of insulin glargine (Gla-300) with other basal insulin therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Design

This was a network meta-analysis (NMA) of randomised clinical trials of basal insulin therapy in T2DM identified via a systematic literature review of Cochrane library databases, MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process, EMBASE and PsycINFO.

Outcome measures

Changes in HbA1c (%) and body weight, and rates of nocturnal and documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia were assessed.

Results

41 studies were included; 25 studies comprised the main analysis population: patients on basal insulin-supported oral therapy (BOT). Change in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was comparable between Gla-300 and detemir (difference: −0.08; 95% credible interval (CrI): −0.40 to 0.24), neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH; 0.01; −0.28 to 0.32), degludec (−0.12; −0.42 to 0.20) and premixed insulin (0.26; −0.04 to 0.58). Change in body weight was comparable between Gla-300 and detemir (0.69; −0.31 to 1.71), NPH (−0.76; −1.75 to 0.21) and degludec (−0.63; −1.63 to 0.35), but significantly lower compared with premixed insulin (−1.83; −2.85 to −0.75). Gla-300 was associated with a significantly lower nocturnal hypoglycaemia rate versus NPH (risk ratio: 0.18; 95% CrI: 0.05 to 0.55) and premixed insulin (0.36; 0.14 to 0.94); no significant differences were noted in Gla-300 versus detemir (0.52; 0.19 to 1.36) and degludec (0.66; 0.28 to 1.50). Differences in documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia rates of Gla-300 versus detemir (0.63; 0.19to 2.00), NPH (0.66; 0.27 to 1.49) and degludec (0.55; 0.23 to 1.34) were not significant. Extensive sensitivity analyses supported the robustness of these findings.

Conclusions

NMA comparisons are useful in the absence of direct randomised controlled data. This NMA suggests that Gla-300 is also associated with a significantly lower risk of nocturnal hypoglycaemia compared with NPH and premixed insulin, with glycaemic control comparable to available basal insulin comparators.

Keywords: DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first comprehensive literature review and network meta-analysis (NMA) summarising the available clinical trial literature on the clinical benefits of the newly approved basal insulin, Gla-300, and potential basal insulin comparators, and enabling comparisons between these therapies.

The systematic literature review was limited to only English language literature; while this is likely to include all major randomised clinical trials conducted for basal insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), it may exclude smaller studies with no publication in English.

The NMA was conducted in accordance with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance and extensive sensitivity analyses were utilised to assess the robustness of the findings.

While NMA enables the synthesis of available clinical information, it is not a substitute for head-to-head clinical trials to compare therapies, and such trials should be encouraged and conducted.

Introduction

Worldwide, approximately 348.3 million people are living with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 2 As T2DM progresses, insulin therapy may be required to achieve glycaemic control. The 2015 ADA/EASD Position Statement on Managing Hyperglycemia in T2DM recommends initiating basal insulin in combination with oral therapy among the appropriate options for patients who are unable to achieve their glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) target after 3 months of metformin monotherapy.3

Insulin glargine 300 u/mL (Gla-300) is a new basal insulin that has recently (2015) been approved by the European Commission and the US Food and Drug Administration. Gla-300 is a concentrated formulation of insulin glargine 100 u/mL (Gla-100), developed to produce a more flat and more prolonged pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile.4–6 Several randomised controlled clinical safety and efficacy trials comparing Gla-300 to Gla-100 have shown that Gla-300 achieves reduction in HbA1c comparable to that of Gla-100, while lowering the risk of hypoglycaemia.6–8 Comparable HbA1c reduction is expected given that each treatment group utilised the same dose titration to achieve fasting plasma glucose of 4.4–5.6 mmol/L (ie, treat-to-target approach). The lower hypoglycaemia rates observed with Gla-300 may be due to properties inherent to the glargine molecule that lead to pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic differences at varying concentrations (ie, between Gla-300 and Gla-100).4 5

At the present time, head-to-head studies of Gla-300 with other available basal insulin options have not been conducted; however, such comparisons would help determine the place in therapy for this product. Meta-analysis enables the findings from multiple primary studies with comparable outcome measures to be combined.9 In absence of direct head-to-head clinical trials, mixed treatment meta-analysis (also known as network meta-analysis (NMA)) may be used to estimate comparative effects of multiple interventions using indirect evidence.9 The current report is an NMA conducted to indirectly compare the efficacy and safety of U300 versus available intermediate-acting to ultra-long-acting basal insulin formulations in the treatment of T2DM.

Methods

Systematic literature review

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify evidence for the clinical efficacy and safety of insulin regimens in T2DM according to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) standards.9 The following electronic databases were searched: the Cochrane Library (eg, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE)), MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process (using Ovid platform), EMBASE (using Ovid Platform) and PsycINFO. Congresses searched were the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD; 2011–2013), the American Diabetes Association (ADA; 2011–2013) and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF; 2011 and 2013). Key search terms included: ‘diabetes mellitus, type 2/’, ‘glargine’, ‘detemir’, ‘degludec’, ‘NPH’, ‘neutral protamine hagedorn’, ‘biphasic’, ‘aspart protamine’, ‘novomix’ and ‘premix’. Searches were limited to human, English-language only articles published from 1980 onwards. The NMA focused on studies published recently (ie, based on availability of basal insulin analogues). At the time of analysis, the Gla-300 vs Gla-100 studies were only available in clinical study reports; however, these studies have subsequently been published.6–8

Several quality control procedures were in place to ensure appropriate study selection and data extraction. Screening of abstracts and full-text was conducted by two independent researchers (a third independent researcher made a final determination for articles for which there was uncertainty). Data extraction was also conducted by two independent researchers (with reconciliation of discrepancies). Where available, full-text versions of the article were used for data extraction (an abstract or poster was not used unless it was the terminal source document). All processes were documented by the researchers and the data extraction file was also quality checked. The source materials (abstracts, full-text articles) and data extraction files were sorted, and saved on a secure server.

Inclusion criteria

In order to be considered for the NMA, clinical studies identified by the systematic literature review had to meet the following criteria: randomised active comparator-controlled clinical studies, patient population of adults with T2DM treated with basal insulin (with or without bolus), patients could be newly initiating insulin (naïve) or already exposed to insulin, and a minimum follow-up of 20 weeks. In addition, studies were required to have patients from at least one of the following countries: the USA, France, Germany, the UK, Spain and/or Italy.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures analysed by NMA included change in HbA1c (%) from baseline, change in body weight (kg) from baseline and rates of hypoglycaemic events (documented symptomatic and/or nocturnal) per patient year. A documented symptomatic event was defined as an event during which typical symptoms of hypoglycaemia were accompanied by measured plasma glucose under a threshold value. In the EDITION trials, the results were reported using both a concentration of ≤3.0 mmol/L and of ≤3.9 mmol/L. No restriction on the threshold levels was imposed. A 3.9 mmol/L threshold for the EDITION trials was selected to be consistent with the majority of other trials in the network. Nocturnal hypoglycaemic events were defined as any event (confirmed and/or symptomatic) occurring during a period at night.

Statistical methods

All analyses were implemented using the statistical software R and OpenBUGS, specifically the packages using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). Examples of coding used are provided in an online supplemental appendix. Randomised clinical trials that were identified from a systematic literature review and that met the study selection inclusion criteria were analysed using a random-effect Bayesian NMA, following the UK NICE guidance.9 Each outcome was analysed within the evidence network where it was reported. MCMC was used to estimate the posterior distribution for treatment comparison. Continuous outcomes (eg, change in HbA1c or body weight) were modelled assuming a normal likelihood and an identity link. Event rate data (eg, number of hypoglycaemic episodes per patient-year follow-up) were modelled using a Poisson mixed likelihood and log link. Non-informative priors were assumed.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses including meta-regression were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the findings. The base scenario included studies of patients on basal insulin-supported oral therapy (BOT; patients received basal insulin in combination with oral antihyperglycaemic drugs but with no bolus insulin; patients could be either—insulin naïve or insulin experienced). Additional scenarios were all studies (ie, patients receiving basal insulin with or without bolus), studies of patients on BOT excluding premixed studies, studies of insulin-naïve patients only, only studies with Week 24–28 results, and excluding degludec three times weekly (3TW) dosing. Meta-regression was conducted for key outcomes to account for study-level population characteristics, adjusting for the following: study-level baseline HbA1c, diabetes disease duration and basal-bolus population. In addition, broader definitions for hypoglycaemia were analysed. A comparison of NMA to classical meta-analysis in the base scenario (BOT) using an inverse variance-weighted method was also conducted.

Results

Systematic literature review

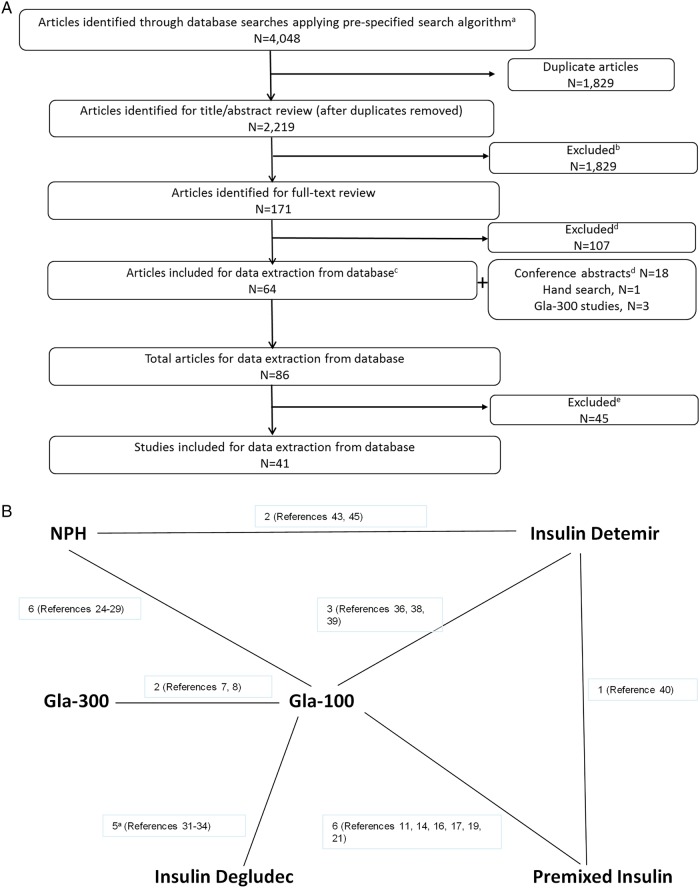

Over 4000 studies were identified for screening, of which 86 were identified for data extraction; from these, 41 studies were included in the NMA (figure 1A). A brief overview of these studies is provided in table 1.

Figure 1.

(A) PRISMA flow diagram for studies comparing basal insulin therapies in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM; N=41). aCochrane Library (eg, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE)), MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process (using Ovid platform), Embase (using Ovid Platform) and PsycINFO; If applicable, relevant results from clinical trial registry were included. Zinman et al34 report 2 distinct studies within 1 publication. bFor title/abstract and full-text review, articles were excluded based on inclusion/exclusion criteria as specified in the systematic literature review. cTwo articles analysed the same trial. dConferences searched included EASD and ADA 2011–2013, and IDF 2011. IDF 2013 was assessed when the CD-ROM became available—the end of February. Multiple abstracts examined the same trial and 14 trials were extracted. eStudies must include at least two treatment arms in the network, including: U300, insulin glargine, insulin detemir, insulin NPH, insulin degludec and premix insulin. (B) Evidence network diagram for BOT studies (n=25) reporting HbA1c (%) change from baseline. Each insulin treatment is a node in the network. The links between the nodes represent direct comparisons. The numbers along the lines indicate the number of trials or pairs of trial arms for that link in the network. Reference numbers indicate the trials contributing to each link. BOT, basal insulin-supported oral therapy; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn.

Table 1.

Randomised comparative studies included in NMA of patients with T2DM on basal insulin treatment

| First author, year published (Regimen type) | Countries/Continents | Key inclusion criteria | N* | Randomised comparator arms | Allocation method | Study duration | Discontinuation rate† | Outcomes in current NMA‡ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |||||||||

| Gla-300 vs Gla-100 | Bolli, 20158 | North America, Europe, Japan | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7–11% |

873 | Gla-300 Gla-100 |

IVRS | 6 months | Gla-300: 62/439 (14%) Gla-100: 75/439 (17%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Riddle, 20146 | North America, Europe, South Africa | On basal bolus insulin regimen HbA1c 7–10% |

806 | Gla-300 + bolus Gla-100 + bolus |

IVRS | 6 months | Gla-300: 30/404 (7.4%) Gla-100: 31/402 (7.7%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Yki-Järvinen, 20147 | North America, Europe, Russia, South America, South Africa | On basal insulin OAD HbA1c 7–10% |

809 | Gla-300 Gla-100 |

IVRS | 6 months | Gla-300: 36/404 (8.9%) Gla-100: 38/407 (9.3%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Gla-100 vs premixed insulin | Aschner, 201310 | NR | Insulin naïve OAD |

923 | Premixed Gla-100±glulisine |

NR | 24 weeks | NR (meeting abstract) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Buse, 200911 | Australia, Europe, India, North America, South America | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c >7% |

2091 | Lispro protamine/lispro 75/25 Gla-100 |

IVRS | 24 weeks | Premixed insulin:145/1045 (13.9%) Gla-100: 128/1046 (12.2%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Fritsche, 201012 | Europe and Australia | Premixed insulin +/- Metformin HbA1c 7.5–11.0% |

310 | 70/30 NPH + bolus (regular or aspart) Gla-100 + glulisine |

Electronic case record system | 52 weeks | Premixed insulin: 28/157 (17.8%) Gla-100:25/153 (16.3%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Jain, 201013 | Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, Russian Federation | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c ≥7.5–12% |

484 | Insulin lispro 50/50 Gla-100 + lispro |

TS | 36 weeks | Premixed insulin: 31/242 (12.8%) Gla-100: 27/242 (11.2%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Kann, 200614 | Europe | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c >7–12% |

255 | Insulin aspart 70/30+ metformin Gla-100 + glimepiride |

Sealed codes | 28 weeks | Premixed insulin: 13/130 (10.0%) Gla-100: 12/128 (9.4%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Kazda, 200615 | Germany | Insulin naïve HbA1c 6–10.5% |

159 | Protaminatedlispro/lispro 50/50 Lispro Gla-100 |

NR | 24 weeks | Premixed insulin: 14.8%§ Bolus insulin: 7.7%§ Gla-100: 15.1%§ |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Ligthelm, 201116 | USA and Puerto Rico | On basal insulin OAD HbA1c ≥8% |

279 | Biphasic aspart 70/30 Gla-100 |

IVRS | 24 weeks | Premixed insulin: 19/137 (13.9%) Gla-100: 32/143 (22.4%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Raskin, 200517 | USA | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c ≥8% |

222 | Biphasic aspart 70/30 Gla-100 |

Sequential numbers/codes | 28 weeks | Premixed insulin:17/117 (14.5%) Gla-100: 7/116 (6.0%) |

✓ | ||||

| Riddle, 201118 | NR | OAD | 572 | Protamine-aspart/aspart 70/30 Glargine + 1 prandial Glulisine Gla-100 + glulisine (stepwise addition) |

NR | 60 weeks | NR (meeting abstract) | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Robbins, 200719 | Australia, Europe, India, North America (USA and Puerto Rico) | OAD HbA1c 6.5–11% |

315 | Lispro 50/50 + metformin Gla-100+metformin |

TS | 24 weeks | Premixed insulin: 15/158 (9.5%) Gla-100: 22/159 (13.8%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Rosenstock, 200820 | USA and Puerto Rico | On basal insulin OAD HbA1c 7.5–12% |

374 | Insulin lispro protamine/lispro Gla-100 + lispro |

TS | 24 weeks | Premixed insulin: 29/187 (15.5%) Gla-100: 29/187 (15.5%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Strojek, 200921 | Asia, Europe, North America, South America, South Africa | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c >7–11% |

469 | Biphasic aspart 70/30 + metformin/glimepiride Gla-100 +metformin/glimepiride |

IVRS | 26 weeks | Premixed insulin: 26/239 (10.9%) Gla-100: 21/241 (8.7%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Tinahones, 201322 | 11 countries (not specified) | On basal insulin OAD HbA1c 7.5–10.5% |

478 | Lispro mix 25/75 Gla-100 + lispro |

NR | 24 weeks | NR (meeting abstract) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Vora, 201323 | NR | On basal insulin | 335 | Biphasic insulin aspart/aspart protamine 30/70 Gla-100 + glulisine |

NR | 24 weeks | Premixed insulin: 23/165 (13.9%) Gla-100: 14/170 (8.2%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Gla-100 vs NPH | Fritsche, 200324 | Europe | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7.5–10.5% |

695 | NPH Gla-100 (morning) Gla-100 (bedtime) |

Sequential numbers/codes | 28 weeks | NPH: 27/234 (11.5%) Gla-100 (morning): 12/237 (5.1%) Gla-100 (bedtime):18/229 (7.9%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Massi Benedetti, 200325 | Europe, South Africa | OAD | 570 | NPH Gla-100 |

Sequential numbers/codes | 52 weeks | NPH: 33/285(11.6%) Gla-100: 16/293 (5.5%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Riddle, 200326 | North America | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7.5–10% |

756 | NPH Gla-100 |

IVRS | 24 weeks | NPH: 32/392 (8.2%) Gla-100: 33/372 (8.9%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Rosenstock, 200127 | NR | On insulin HbA1c 7–12% |

518 | NPH Gla-100 |

NR | 28 weeks | NPH: 21/259 (8.1%) Gla-100: 28/259 (10.8%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Rosenstock 200928 | North America | OAD HbA1c 6–12% |

1017 | NPH Gla-100 |

IVRS | 5 years | NPH: 145/509 (28.5%)§ Gla-100: 141/515 (27.4%)§ |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Yki-Järvinen, 200629 | Europe | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c ≥8% |

110 | NPH Gla-100 |

NR | 36 weeks | NPH: 1/49 (2.0%) Gla-100: 1/61 (1.6%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Degludec vs Gla-100 | Garber, 201230 | Asia (Hong Kong), Europe, Middle East (Turkey), North America, Russia, South Africa | On insulin ±OAD HbA1c 7–10% |

1004 | Degludec + aspart Gla-100 + aspart |

IVRS | 52 weeks | Degludec: 137/755 (18.1%) Glargine:40/251 (15.9%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gough, 201331 | Europe, North America, Russia, South Africa | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7–10% |

456 | Degludec Gla-100 |

IVRS | 26 weeks | NR§ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Meneghini, 201332 | Asia, Europe, Israel, North America, Russia, South America, South Africa | OAD HbA1c 7–11% |

685 | Degludec (flexible) Degludec (once daily) Gla-100 |

IVRS | 26 weeks | Degludec(flexible): 26/229 (11.4%) Degludec(once daily): 24/228 (10.5%) Gla-100: 27/230 (11.7%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Zinman, 201233 | Europe, North America | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7–10% |

1023 | Degludec Gla-100 |

IVRS | 52 weeks | Degludec: 166/773 (21.5%) Glargine:60/257 (23.3%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Zinman (AM), 201334 | Europe, Israel, North America, South Africa | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7–10% |

456 | Degludec Gla-100 |

IVRS | 26 weeks | Degludec: 38/230 (16.5%) Gla-100: 24/230 (10.4%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Zinman (PM), 201334 | Europe, North America | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7–10% |

467 | Degludec Gla-100 |

IVRS | 26 weeks | Degludec: 25/233 (10.7%) Gla-100: 25/234 (10.7%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Detemir vs Gla-100 | Hollander, 200835 | Europe and the USA | OAD and/or insulin HbA1c 7–11% |

319 | Detemir + aspart Gla-100 + aspart |

TS | 52 weeks | Detemir: 43/216 (19.9%) Gla-100: 23/107 (21.5%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Meneghini, 201336 | Asia, South America, USA | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7–9% |

453 | Detemir Gla-100 |

NR | 26 weeks | Detemir: 38/228 (16.7%) Gla-100: 41/229 (17.9%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Raskin, 200937 | NR | OAD and/or insulin HbA1c 7–11% |

387 | Detemir + aspart Gla-100 + aspart |

NR | 26 weeks | Detemir: 46/256 (18.0%) Gla-100: 18/131 (13.7%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Rosenstock, 200838 | Europe and the USA | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7.5–10% |

582 | Detemir Gla-100 |

TS | 52 weeks | Detemir: 60/291 (20.6%) Gla-100: 39/291 (13.4%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Swinnen, 201039 | Asia, Australia, Europe, Middle East (Turkey), North America, Russia, South America | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7–10.5% |

964 | Detemir Gla-100 |

NR | 24 weeks | Detemir: 10.1%§ Gla-100:4.6%§ |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Detemir vs premixed | Holman, 200740 | Europe | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7–10% |

708 | Prandial insulin aspart Detemir Biphasic aspart 30 |

IVRS | 52 weeks | Bolus: 17/239 (7.1%) Detemir: 10/234 (4.3%) Premixed insulin:13/235 (5.5%) |

✓ | ✓ | ||

| Liebl, 200941 | Europe | OAD HbA1c 7–12% |

715 | Detemir + aspart Soluble aspart/protamine-crystallised aspart 30/70 |

Codes | 26 weeks | Detemir: 44/541 (8.1%) Premixed insulin: 17/178 (9.6%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Detemir vs NPH | Haak, 200542 | Europe | HbA1c ≤12% | 505 | Detemir + aspart NPH + aspart |

NR | 26 weeks | Detemir: 26/341 (7.6%)§ NPH: 8/164 (4.9%)§ |

✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hermansen, 200643 | Europe | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7.5–10% |

475 | Detemir NPH |

TS | 24 weeks | Detemir: 4%§ NPH: 5%§ |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Montañana, 200844 | Spain | On insulin± metformin HbA1c 7.5–11% |

271 | Detemir + aspart NPH + aspart |

Codes | 26 weeks | Detemir:7/126 (5.6%) NPH: 12/151 (7.9%) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Philis-Tsimakas, 200645 | North America and Europe | Insulin naïve OAD HbA1c 7.5–11% |

498 | Detemir morning Detemir evening NPH |

IVRS | 20 weeks | Detemir (morning): 19/168 (11.3%) Detemir (evening): 16/170 (9.4%) NPH: 17/166 (10.2%) |

✓ | ✓ | |||

| Raslová, 200446 | 8 Countries (not specified) | On insulin ±OADs HbA1c <12% |

394 | Detemir + insulin aspart NPH + human soluble insulin |

NR | 22 weeks | Detemir: 10/195 (5.1%)§ NPH: 6/199 (3.0%)§ |

✓ | ✓ | |||

All the studies were open-label, with the exception of Liebl et al1 (not reported).

*Safety population; exceptions: efficacy population for Buse et al,11 Raslová et al,46 Riddle et al,18 Tinahones et al22 and Vora et al.23

†Numerator for discontinuation rate=randomised patients−patients completing the study; denominator for discontinuation rate=randomised patients. Exceptions noted in footnote (§).

‡A=change in HbA1c, B=change in body weight, C=nocturnal hypoglycaemia rate, D=documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia rate.

§Exceptions to definition of discontinuation rate/or discontinuation rate not calculable with information available: Gough 2013 reported that 460 were randomised 1:1 (3 were randomised in error and were withdrawn, 1 withdrew consent (all prior to treatment)) and 228 and 229 received detemir and Gla-100, respectively, however, completion/withdrawal not described; Kazda et al15 reported ‘drop-out’ rates (however, numbers randomised to each group not provided and denominator may have been exposed rather than randomised patients); Swinnen et al's39 brief report does not make clear what the denominator was for completion rate provided (did not report number randomised to each group, only total randomised; did not report numbers of patients completing the study—only the percentages); Hermansen et al:43 denominator may be ITT population—475 were randomised but the breakdown between treatment arms is not clear; Haak et al,42 reported rates based on patients receiving treatment rather than randomised patients; Raslová et al46 reported rates reported based on ITT rather than randomised patients (ITT only 1 less than randomised, but number randomised to each treatment arm not provided in publication). In addition, Rosenstock et al28 reported data over 5 years; however, only the first year data were included in this NMA.

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; ITT, intention to treat; IVRS, interactive voice (or web) response system; NMA, network meta-analysis; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn;

NR, not reported; OAD,oral antidiabetic medication; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TS, telephone system.

Included trials

All studies were randomised based on entry criteria, with interactive voice (or web) response system or telephone system as the main method of randomisation (n=22), followed by use of sequential numbers/codes (n=6) and electronic case record system (n=1); the method of randomisation was either not reported or not clear in the remaining studies (n=12). The majority (40/41) of studies specified an open-label in design (1 study did not specify). Loss to follow-up (ie, rates of discontinuation among randomised patients) among the studies ranged from 1.6% to 28.5%, with 10 studies reporting discontinuation rates <10%, 22 reporting 10–20% and 5 reporting >20% in at least one treatment arm (loss to follow-up was not reported in 4 studies). The baseline patient characteristics of patients in each of the 41 studies are provided in table 2.

Table 2.

Patient baseline characteristics for trials included in the NMA (N=41)

| First author | Year | Age Mean±SD |

Male (%) | Diabetes duration (years) Mean±SD |

HbA1c (%), Mean±SD | Body weight (kg) Mean±SD |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gla-100 vs Gla-300 | Bolli8 | 2015 | 57.7±10.1 | 57.8 | 9.8±6.4 | 8.5±1.1 | 95.4±23.0 |

| Riddle6 | 2014 | 60.0±8.6 | 52.9 | 15.9±7.5 | 8.1±0.8 | 106.3±20.8 | |

| Yki-Järvinen7 | 2014 | 58.2±9.2 | 45.9 | 12.6±7.1 | 8.3±0.8 | 98.4±21.6 | |

| Gla-100 vs premixed | Aschner10 | 2013 | NA | NA | NA | 8.7±0 | NA |

| Buse11 | 2009 | 57.0±10 | 52.80 | 9.5±6.1 | 9.1±1.3 | 88.50±21.0 | |

| Fritsche12 | 2010 | 60.6±7.7 | 50.91 | 12.7±6.3 | 8.6±0.9 | 85.61±15.1 | |

| Jain13 | 2010 | 59.4±9.2 | 48.78 | 11.7±6.5 | 9.4±1.2 | 78.5±15.3 | |

| Kann14 | 2006 | 61.3±9.1 | 51.4 | 10.25±7.1 | 9.1±1.4 | 85.4±15.5 | |

| Kazda15 | 2006 | 59.4±9.5 | 54.7 | 5.6±2.9 | 8.1±1.2 | NA | |

| Ligthelm16 | 2011 | 52.7±10.4 | 56.66 | 11.15±6.4 | 9.0±1.1 | 97.9±20.5 | |

| Raskin17 | 2005 | 52.5±10.2 | 54.5 | 9.2±5.3 | 9.8±1.5 | 90.2±18.9 | |

| Riddle18 | 2011 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Robbins19 | 2007 | 57.8±9.1 | 49.9 | 11.9±6.3 | 7.8±1.0 | 88.6±19.7 | |

| Rosenstock20 | 2008 | 54.7±9.5 | 52.5 | 11.1±6.3 | 8.9±1.1 | 99.5±20.6 | |

| Strojek21 | 2009 | 56.0±9.9 | 43.96 | 9.3±6.0 | 8.5±1.1 | NA | |

| Tinahones22 | 2013 | NA | NA | NA | 8.6±0.8 | NA | |

| Vora23 | 2013 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Gla-100 vs NPH | Fritsche24 | 2003 | 61.0±9.0 | 53.7 | NA | 9.1±1.0 | 81.3±14.8 |

| MassiBenedetti25 | 2003 | 59.5±9.2 | 53.7 | 10.35±6.1 | 9.0±1.2 | NA | |

| Riddle26 | 2003 | 55.5±9.2 | 55.5 | 8.71±5.56 | 8.6±0.9 | NA | |

| Rosenstock27 | 2001 | 59.4±9.8 | 60.1 | 13.75±8.65 | 8.6±1.2 | 90.2±17.6 | |

| Rosenstock28 | 2009 | 55.1±8.7 | 53.9 | 10.75±6.8 | 8.4±1.4 | 99.5±22.5 | |

| Yki-Järvinen29 | 2006 | 56.5±1 | 63.3 | 9±1 | 9.5±0.1 | 93.1±2.5 | |

| Degludec vs Gla-100 | Garber30 | 2012 | 58.9±9.3 | 54.0 | 13.6±7.3 | 8.3±0.8 | 92.5±17.7 |

| Gough31 | 2013 | 57.6±9.2 | 53.2 | 8.2±6.2 | 8.3±1.0 | 92.5±18.5 | |

| Meneghini32 | 2013 | 56.5±9.6 | 53.7 | 10.6±6.7 | 8.4±0.9 | 81.7±16.7 | |

| Zinman33 | 2012 | 59.2±9.8 | 61.9 | 9.2±6.2 | 8.2±0.8 | 90.0±17.3 | |

| Zinman (PM)34 | 2013 | 57.4±10.2 | 57.2 | 8.8±3.4 | 8.3±0.8 | 91.9±18.5 | |

| Zinman (AM)34 | 2013 | 58.2±9.8 | 56.9 | 8.9±6.1 | 8.3±0.9 | 93.3±18.8 | |

| Detemir vs Gla-100 | Hollander35 | 2008 | 58.7±11 | 58.0 | 13.5±8.0 | 8.7±1.0 | 92.7±17.6 |

| Meneghini36 | 2013 | 57.3±10.3 | 56.5 | 8.2±6.1 | 7.91±0.6 | 82.3±16.7 | |

| Raskin37 | 2009 | 55.8±10.3 | 54.6 | 12.3±7.0 | 8.4±1 | 95.6±18.2 | |

| Rosenstock38 | 2008 | 58.9±9.9 | 57.9 | 9.1±6.3 | 8.6±0.8 | 87.4±17.0 | |

| Swinnen39 | 2010 | 58.4±8.3 | 54.7 | 9.9±5.8 | 8.7±0.9 | 83.9±17.1 | |

| Detemir vs premixed | Holman40 | 2007 | 61.7±9.8 | 64.1 | NA | 8.5±0.8 | 85.8±15.9 |

| Liebl41 | 2009 | 60.7±9.2 | 58.5 | 9.3±6.4 | 8.5±1.1 | NA | |

| Detemir vs NPH | Haak42 | 2005 | 60.4±8.6 | 51.1 | 13.2±7.6 | 7.9±1.3 | 86.9±15.8 |

| Hermansen43 | 2006 | 60.9±9.2 | 53.1 | 9.7±6.4 | 8.6±0.8 | 82.6±13.8 | |

| Montañana44 | 2008 | 61.9±8.8 | 40.6 | 16.3±8.0 | 8.85±1.0 | 81.0±12.1 | |

| Philis-Tsimakas45 | 2006 | 58.5±10.5 | 56.8 | 10.3±7.2 | 9.0±1.0 | NA | |

| Raslová46 | 2004 | 58.3±9.3 | 42.1 | 14.1±7.8 | 8.1±1.3 | 80.8±12.7 |

HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; NA, not applicable; NMA, network meta-analysis; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn.

Twenty-five of the 41 studies (61%) were of patients on BOT (main population for this analysis; n=15 746 patients). The evidence network for the BOT studies is depicted in figure 1B. Patients in the BOT studies had a mean age ranging from 52.4 to 61.7 years, duration of diabetes 8.2–13.8 years, baseline body weight 81.3–99.5 kg and HbA1c 7.8–9.8%.

Glycaemic control

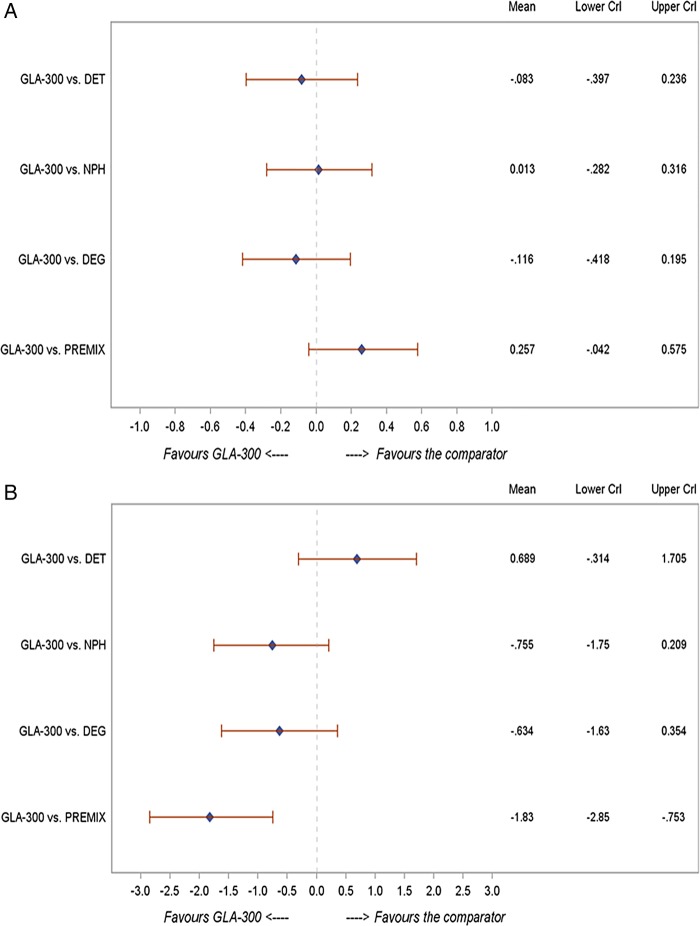

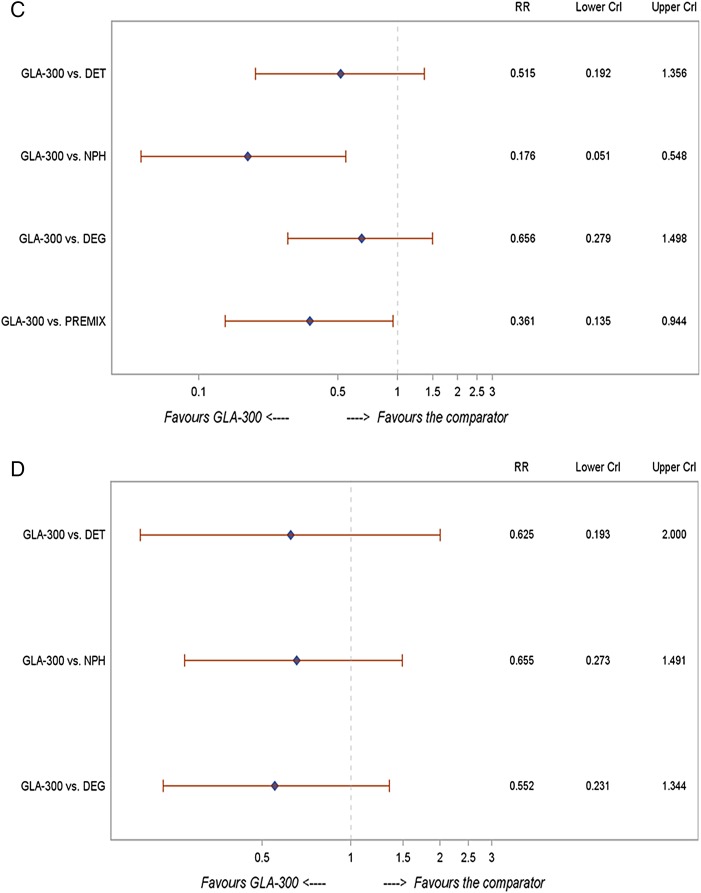

In patients with T2DM on BOT (n=25 studies), the change in HbA1c was comparable between Gla-300 and insulin detemir (−0.08; −0.40 to 0.24), neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH; 0.01; −0.28 to 0.32), degludec (−0.12; −0.42 to 0.20) and premixed insulin (0.26; −0.04 to 0.58) (figure 2A). These changes were similar to those in the overall NMA (n=41 studies) and across the various sensitivity analyses shown in table 3A.

Figure 2.

NMA findings for Gla-300 versus other basal insulins in the BOT population: (A) change in HbA1c (%); (B) change in body weight (kg); (C) risk of nocturnal hypoglycaemia; (D) risk of documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia. BOT, basal insulin-supported oral therapy; CrI, credible interval; DET, =insulin detemir; DEG, insulin degludec; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; NMA, network meta-analysis; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn; PREMIX, premixed insulin; RR, risk ratio.

Table 3.

Additional analyses

| (A) Sensitivity analyses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Comparator |

||||

| Gla-100 | Detemir | NPH | Degludec | Premix | |

| Change in HbA1c* | |||||

| BOT, insulin naïve | 0.01 (−0.27 to 0.29) | −0.14 (−0.47 to 0.19) | −0.09 (−0.43 to 0.25) | −0.12 (−0.45 to 0.21) | 0.08 (−0.23 to 0.39) |

| Adjusting for Bolus Insulin Trials | −0.01 (−0.44 to 0.42) | −0.10 (−0.55 to 0.36) | −0.05 (−0.51 to 0.41) | −0.14 (−0.60 to 0.33) | 0.07 (−0.37 to 0.51) |

| Insulin naïve | 0.04 (−0.41 to 0.48) | −0.09 (−0.59 to 0.40) | −0.06 (−0.55 to 0.43) | −0.12 (−0.62 to 0.37) | 0.24 (−0.22 to 0.72) |

| T2DM overall | 0.01 (−0.23 to 0.25) | −0.08 (−0.37 to 0.21) | −0.03 (−0.32 to 0.26) | −0.12 (−0.42 to 0.18) | 0.09 (−0.18 to 0.35) |

| Studies reporting hypoglycaemia data | 0.01 (−0.23 to 0.25) | −0.18 (−0.51 to 0.14) | −0.09 (−0.57 to 0.38) | −0.12 (−0.42 to 0.18) | 0.18 (−0.12 to 0.51) |

| Studies with 24–28-week results | 0.01 (−0.24 to 0.26) | −0.04 (−0.36 to 0.27) | −0.03 (−0.35 to 0.30) | −0.14 (−0.47 to 0.19) | 0.17 (−0.10 to 0.45) |

| Excluding Degludec 3TW | 0.02 (−0.22 to 0.28) | −0.08 (−0.37 to 0.22) | 0.01 (−0.26 to 0.30) | −0.01 (−0.32 to 0.31) | 0.26 (−0.02 to 0.55) |

| Adjusting for baseline HbA1c | 0.05 (−0.49 to 0.63) | −0.03 (−0.60 to 0.56) | 0.02 (−0.56 to 0.61) | −0.07 (−0.65 to 0.53) | 0.13 (−0.42 to 0.72) |

| Adjusting for disease duration | 0.03 (−0.29 to 0.34) | −0.06 (−0.41 to 0.29) | −0.01 (−0.37 to 0.35) | −0.10 (−0.46 to 0.26) | 0.11 (−0.23 to 0.44) |

| Change in body weight | |||||

| BOT, insulin naïve | −0.44 (−1.67 to 0.81) | 0.58 (−0.85 to 2.03) | −0.22 (−1.68 to 1.25) | −0.52 (−1.93 to 0.92) | −1.09 (−2.44 to 0.29) |

| Adjusting for Bolus Insulin Trials | −0.58 (−2.54 to 1.37) | 0.11 (−1.98 to 2.20) | −0.63 (−2.75 to 1.45) | −0.66 (−2.78 to 1.45) | −1.13 (−3.18 to 0.91) |

| Insulin naïve | −0.30 (−1.44 to 0.82) | 1.18 (−0.12 to 2.47) | −0.12 (−1.39 to 1.10) | −0.46 (−1.71 to 0.80) | −1.12 (−2.39 to 0.15) |

| T2DM overall | −0.27 (−1.28 to 0.73) | 0.42 (−0.78 to 1.62) | −0.32 (−1.54 to 0.89) | −0.35 (−1.58 to 0.88) | −0.81 (−1.96 to 0.32) |

| Studies reporting hypoglycaemia data | −0.28 (−1.28 to 0.71) | 1.01 (−0.29 to 2.31) | 0.89 (−0.90 to 2.70) | −0.36 (−1.58 to 0.86) | −1.24 (−2.59 to 0.09) |

| Studies with 24–28-week results | −0.28 (−1.28 to 0.74) | 0.26 (−1.05 to 1.57) | −0.15 (−1.45 to 1.16) | −0.42 (−1.76 to 0.92) | −1.01 (−2.19 to 0.18) |

| Excluding Degludec 3TW | −0.46 (−1.34 to 0.43) | 0.68 (−0.38 to 1.76) | −0.76 (−1.82 to 0.27) | −0.79 (−1.90 to 0.33) | −1.83 (−2.89 to −0.68) |

| Adjusting for baseline HbA1c | −0.27 (−2.03 to 1.25) | 0.43 (−1.46 to 2.12) | −0.32 (−2.23 to 1.39) | −0.34 (−2.26 to 1.38) | −0.81 (−2.68 to 0.82) |

| Adjusting for disease duration | −0.44 (−1.91 to 1.00) | 0.25 (−1.38 to 1.87) | −0.49 (−2.15 to 1.13) | −0.52 (−2.20 to 1.13) | −0.99 (−2.58 to 0.58) |

| Nocturnal hypoglycaemia event rate | |||||

| BOT, insulin naïve | 0.57 (0.33 to 0.98) | 0.53 (0.28 to 1.01) | 0.21 (0.10 to 0.44) | 0.68 (0.36 to 1.25) | 0.42 (0.21 to 0.81) |

| BOT, premixed excluded | 0.62 (0.37 to 1.17) | 0.56 (0.30 to 1.21) | 0.16 (0.08 to 0.41) | 0.79 (0.42 to 1.64) | N/A |

| Adjusting for Bolus Insulin Trials | 0.56 (0.24 to 1.29) | 0.52 (0.21 to 1.32) | 0.20 (0.07 to 0.57) | 0.66 (0.26 to 1.61) | 0.50 (0.19 to 1.26) |

| Insulin naïve patients only | 0.58 (0.12 to 2.77) | 0.51 (0.07 to 3.38) | 0.17 (0.02 to 1.37) | 0.61 (0.10 to 3.48) | 0.26 (0.03 to 2.35) |

| T2DM overall | 0.64 (0.39 to 1.03) | 0.60 (0.32 to 1.11) | 0.23 (0.11 to 0.50) | 0.75 (0.41 to 1.34) | 0.57 (0.31 to 1.05) |

| Studies with 24–28-week results | 0.64 (0.37 to 1.10) | 0.51 (0.22 to 1.18) | 0.24 (0.08 to 0.70) | 0.67 (0.32 to 1.37) | 0.55 (0.26 to 1.17) |

| Excluding Degludec 3TW | 0.57 (0.33 to 0.98) | 0.51 (0.24 to 1.07) | 0.19 (0.07 to 0.45) | 0.83 (0.42 to 1.69) | 0.36 (0.17 to 0.74) |

| 2.8–4.2 mmol/L | 0.64 (0.37 to 1.11) | 0.68 (0.35 to 1.34) | 0.31 (0.15 to 0.63) | 0.75 (0.38 to 1.46) | 0.68 (0.35 to 1.29) |

| Adjusting for baseline HbA1c | 0.37 (0.18 to 0.90) | 0.35 (0.15 to 0.91) | 0.13 (0.05 to 0.39) | 0.43 (0.19 to 1.12) | 0.33 (0.14 to 0.86) |

| Adjusting for disease duration | 0.60 (0.31 to 1.13) | 0.56 (0.26 to 1.19) | 0.22 (0.09 to 0.53) | 0.71 (0.34 to 1.46) | 0.54 (0.25 to 1.14) |

| Documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia event rate | |||||

| BOT, insulin naïve | 0.72 (0.40 to 1.30) | 0.63 (0.22 to 1.73) | 0.58 (0.26 to 1.24) | 0.59 (0.29 to 1.20) | 0.50 (0.24 to 1.01) |

| BOT, premixed excluded | 0.75 (0.55 to 1.05) | 0.69 (0.42 to 1.23) | 0.55 (0.36 to 0.91) | 0.66 (0.46 to 1.01) | N/A |

| Adjusting for Bolus Insulin Trials | 0.83 (0.35 to 1.83) | 0.72 (0.22 to 2.31) | 0.76 (0.28 to 1.86) | 0.68 (0.26 to 1.67) | 0.57 (0.22 to 1.41) |

| Insulin naïve patients only | 0.62 (0.21 to 1.77) | 0.54 (0.12 to 2.36) | 0.50 (0.14 to 1.63) | 0.61 (0.17 to 2.25) | 0.24 (0.05 to 1.09) |

| T2DM overall | 0.78 (0.50 to 1.23) | 0.68 (0.27 to 1.70) | 0.71 (0.38 to 1.30) | 0.64 (0.36 to 1.16) | 0.54 (0.30 to 0.98) |

| Studies with 24–28-week results | 0.78 (0.45 to 1.34) | 0.68 (0.23 to 2.01) | 0.75 (0.36 to 1.60) | 0.53 (0.23 to 1.20) | 0.58 (0.27 to 1.25) |

| Adjusting for baseline HbA1c | 0.71 (0.44 to 1.13) | 0.61 (0.25 to 1.51) | 0.64 (0.34 to 1.19) | 0.58 (0.32 to 1.05) | 0.49 (0.27 to 0.89) |

| Adjusting for disease duration | 0.57 (0.32 to 0.99) | 0.50 (0.18 to 1.33) | 0.52 (0.25 to 1.04) | 0.47 (0.23 to 0.92) | 0.40 (0.19 to 0.78) |

| (B) Comparison of NMA to classic meta-analysis for base scenario (BOT) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Difference | NMA: point estimate (95% CrI) | Meta-analysis (direct evidence): point estimate (95% CI) |

| Change in HbA1c† | Gla-300 vs Gla-100 | 0.01 (−0.27 to 0.29) | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.11) |

| Insulin detemir vs Gla-100 | 0.10 (−0.07 to 0.28) | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.13) | |

| NPH vs Gla-100 | 0.01 (−0.14 to 0.16) | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.09) | |

| Insulin degludec vs Gla-100 | 0.14 (−0.03 to 0.30) | 0.13 (0.06 to 0.20) | |

| Premixed vs Gla-100 | −0.24 (−0.40 to −0.08) | −0.15 (−0.21 to −0.10) | |

| Change in body weight | Gla-300 vs Gla-100 | −0.44 (−1.67 to 0.81) | −0.48 (−0.83 to −0.13) |

| Insulin detemir vs Gla-100 | −1.15 (−1.73 to −0.58) | −0.98 (−1.20 to −0.76) | |

| NPH vs Gla-100 | 0.30 (−0.21 to 0.84) | 0.01 (−0.22 to 0.25) | |

| Insulin degludec vs Gla-100 | 0.18 (−0.35 to 0.70) | 0.21 (0.03 to 0.38) | |

| Premixed vs Gla-100 | 1.37 (0.72 to 1.97) | 1.70 (1.69 to 1.71) | |

| Nocturnal hypoglycaemia event rate | Gla-300 vs Gla-100 | 0.57 (0.33 to 0.98) | 0.59 (0.38 to 0.90) |

| Insulin detemir vs Gla-100 | 1.11 (0.58 to 2.10) | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.21) | |

| NPH vs Gla-100 | 3.04 (1.24 to 7.80) | NA† | |

| Insulin degludec vs Gla-100 | 0.88 (0.57 to 1.38) | 0.79 (0.67 to 0.93) | |

| Premixed vs Gla-100 | 1.60 (0.84 to 3.10) | 1.39 (1.19 to 1.62) | |

| Documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia event rate | Gla-300 vs Gla-100 | 0.72 (0.40 to 1.30) | 0.75 (0.61 to 0.92) |

| Insulin detemir vs Gla-100 | 1.15 (0.44 to 2.96) | 1.15 (1.07 to 1.24) | |

| NPH vs Gla-100 | 1.10 (0.68 to 1.89) | 1.04 (1.00 to 1.09) | |

| Insulin degludec vs Gla-100 | 1.30 (0.75 to 2.24) | 1.35 (1.27 to 1.44) | |

| Premixed vs Gla-100 | NA† | NA† | |

*Four additional studies were included in sensitivity analyses for HbA1c and/or body weight, but were not in the main NMA.47–50

†No direct evidence for specific comparison.

BOT, basal insulin-supported oral therapy (ie, no bolus insulin); CrI, Credible interval; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; NA, not applicable; NMA, network meta-analysis; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 2.

Continued

Body weight

Change in body weight from baseline was reported in 36 trials in the NMA. Among patients with T2DM on BOT, no statistically significant difference in body weight change was observed between Gla-300 and detemir (difference: 0.69; 95% CrI −0.31 to 1.71), NPH (−0.76; −1.75 to 0.21) or degludec (−0.63; −1.63 to 0.35), whereas weight gain was significantly lower with Gla-300 compared with premixed insulin (−1.83; −2.85 to −0.75) (figure 2B). These changes were similar to those in the overall NMA (n=41 studies) and across the various sensitivity analyses (table 3A).

Hypoglycaemia events

Among the studies identified, 20 trials reported nocturnal hypoglycaemia event rate data and 16 reported documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia event rate data that met criteria for inclusion in the NMA. The hypoglycaemia event data from each of these clinical trials are summarised in table 4.

Table 4.

Hypoglycaemia outcomes for trials included in the NMA

| Study | Year | Arm | Total exposure* | Documented symptomatic | Nocturnal | Severe† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gla-100 vs Gla-300 | ||||||

| Bolli et al8 | 2013 | Gla-100 | 218 | 821 | 41 | 4 |

| Gla-300 | 217 | 505 | 24 | 4 | ||

| Riddle et al6 | 2014 | Gla-100 | 200 | 2957 | 162 | 48 |

| Gla-300 | 201 | 2714 | 127 | 54 | ||

| Yki-Järvinen et al7 | 2014 | Gla-100 | 202 | 1641 | 140 | 12 |

| Gla-300 | 201 | 1357 | 78 | 6 | ||

| Gla-100 vs premixed insulin | ||||||

| Aschner et al10 | 2013 | Gla-100 | 213 | 249 | 5 | |

| Premixed insulin | 212 | 632 | 3 | |||

| Fritsche et al12 | 2010 | Gla-100 | 141 | 321 | 16 | |

| Premixed insulin | 149 | 353 | 33 | |||

| Ligthelm et al16 | 2011 | Gla-100 | 65 | 233 | 6 | |

| Premixed insulin | 63 | 273 | 0 | |||

| Raskin et al17 | 2005 | Gla-100 | 61 | 1 | ||

| Premixed insulin | 58 | 0 | ||||

| Riddle et al18 | 2011 | Gla-100 (plus step-wise glulisine) | 220 | 1559 | ||

| Gla-100 (plus 1 prandial dose) | 217 | 1565 | ||||

| Premixed insulin | 221 | 2694 | ||||

| Robbins et al19 | 2007 | Gla-100 | 73 | 4 | ||

| Premixed insulin | 72 | 8 | ||||

| Rosenstock et al20 | 2008 | Gla-100 | 86 | 3866 | 3 | |

| Premixed insulin | 86 | 4000 | 9 | |||

| Strojek et al21 | 2009 | Gla-100 | 114 | 57 | 3 | |

| Premixed insulin | 110 | 120 | 3 | |||

| Tinahones et al22 | 2013 | Gla-100 | 111 | 859 | ||

| Premixed insulin | 109 | 783 | ||||

| Vora et al23 | 2013 | Gla-100 | 78 | 446 | ||

| Premixed insulin | 76 | 273 | ||||

| Gla-100 vs NPH | ||||||

| Fritsche et al24 | 2003 | Gla-100 (morning dosing) | 109 | 710 | 6 | |

| Gla-100 (evening dosing) | 104 | 467 | 4 | |||

| NPH | 107 | 583 | 13 | |||

| Riddle et al26 | 2003 | Gla-100 | 169 | 1553 | 14 | |

| NPH | 179 | 2308 | 9 | |||

| Rosenstock et al27 | 2001 | Gla-100 | 139 | 2012 | ||

| NPH | 139 | 1577 | ||||

| Rosenstock et al28 | 2009 | Gla-100 | 2556 | 102 | ||

| NPH | 2511 | 151 | ||||

| Yki-Järvinen et al29 | 2006 | Gla-100 | 42 | 5 | 0 | |

| NPH | 34 | 8 | 0 | |||

| Degludec vs Gla-100 | ||||||

| Garber et al30 | 2012 | Degludec | 671 | 13 821 | 932 | 40 |

| Gla-100 | 229 | 5361 | 421 | 11 | ||

| Gough et al31 | 2013 | Degludec | 106 | 357 | 19 | 0 |

| Gla-100 | 107 | 389 | 30 | 0 | ||

| Meneghini et al32 | 2013 | Degludec (flexible dosing)‡ | 108 | 851 | 65 | 2 |

| Degludec (evening dosing) | 105 | 776 | 63 | 2 | ||

| Gla-100 | 105 | 383 | 84 | 2 | ||

| Zinman et al33 | 2012 | Degludec | 667 | 2675 | 167 | 2 |

| Gla-100 | 218 | 806 | 85 | 5 | ||

| Zinman (AM) et al34 | 2013 | Degludec | 105 | 42 | 1 | |

| Gla-100 | 106 | 21 | 1 | |||

| Zinman (PM) et al34 | 2013 | Degludec | 109 | 22 | 1 | |

| Gla-100 | 110 | 22 | 0 | |||

| Detemir vs Gla-100 | ||||||

| Hollander et al35 | 2008 | Detemir | 187 | 449 | 17 | |

| Gla-100 | 92 | 265 | 6 | |||

| Meneghini et al36 | 2013 | Detemir | 103 | 115 | 0 | |

| Gla-100 | 104 | 91 | 2 | |||

| Raskin et al37 | 2009 | Detemir | 128 | 540 | 11 | |

| Gla-100 | 65 | 221 | 8 | |||

| Rosenstock et al38 | 2008 | Detemir | 262 | 341 | 0 | |

| Gla-100 | 269 | 350 | 0 | |||

| Swinnen et al39 | 2010 | Detemir | 224 | 1491 | 18 | |

| Gla-100 | 220 | 1273 | 35 | |||

| Detemir vs premixed insulin | ||||||

| Holman et al40 | 2007 | Detemir | 233 | 4 | ||

| Premixed insulin | 234 | 11 | ||||

| Aspart | 238 | 16 | ||||

| Detemir vs NPH | ||||||

| Hermansen et al43 | 2006 | Detemir | 106 | 160 | 1 | |

| NPH | 106 | 349 | 8 | |||

| Montañana et al44 | 2008 | Detemir | 62 | 46 | 0 | |

| NPH | 73 | 107 | 3 | |||

| Philis-Tsimikas et al45 | 2006 | Detemir (morning dosing) | 63 | 6 | 0 | |

| Detemir (evening dosing) | 65 | 19 | 2 | |||

| NPH | 63 | 47 | 0 | |||

*Total exposure indicates the number of patient-years over which the rate for hypoglycaemic events is determined.

†Although severe events were not analysed in the NMA due to small numbers of events, they are included in the table if reported within the publication.

‡Rotating morning and evening dosing schedule (ie, 8–40 h intervals between doses).

NMA, network meta-analysis; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn.

Nocturnal hypoglycaemia

In patients with T2DM on BOT, Gla-300 was associated with a significantly lower nocturnal hypoglycaemia rate compared with NPH (0.18; 0.05 to 0.55) and premixed insulin (0.36; 0.14 to 0.94) and a numerically lower rate when compared with detemir (0.52; 0.19 to 1.36) and degludec (0.66; 0.28 to 1.50) (figure 2C). These changes were similar to those in the overall NMA (n=41 studies) and across the various sensitivity analyses (table 3A).

Documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia

In patients with T2DM on BOT, Gla-300 was associated with a numerically lower rate of documented symptomatic hypoglycaemic events compared with detemir (0.63; 0.19 to 2.00), NPH (0.66; 0.27 to 1.49) and degludec (0.55; 0.23 to 1.34) (figure 2D). These changes were similar to those in the overall NMA (n=41 studies) and across the various sensitivity analyses (table 3A). In the BOT population, comparative data for premixed insulin were not available for this particular outcome.

Comparison of NMA to classic meta-analysis findings

The comparison of NMA results that integrate all available evidence versus those from classical meta-analysis solely based on direct evidence in the base scenario (BOT) found generally consistent effect size across all four outcomes and tighter 95% CIs with the classical meta-analysis (table 3B).

Discussion

In this NMA of randomised clinical studies comparing various basal insulin therapies in patients with T2DM, the new concentrated formulation, Gla-300, demonstrated change in HbA1c that was comparable to the change reported in studies of insulin detemir, degludec, NPH and premixed insulin. Change in body weight with Gla-300 was significantly less than that with premixed insulin and comparable to the other basal insulin. Hypoglycaemia rates appeared lower with Gla-300 and the comparator basal insulin. The rate of documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia associated with Gla-300 was numerically but not significantly different from that of other basal insulin therapies. A notable difference was that Gla-300 was associated with a significantly lower risk of nocturnal hypoglycaemia (ranging from approximately 64% to 82% lower) compared with premixed insulin and NPH.

These NMA data extend our current knowledge regarding Gla-300. Based on direct comparisons in the EDITION studies, Gla-300 was associated with comparable glycaemic control, but had a significantly lower rate of nocturnal hypoglycaemia compared with Gla-100.6–8 The more flat and more prolonged pharmacokinetic profile associated with Gla-300 compared with Gla-100 may contribute to the reduced rate of nocturnal hypoglycaemia that is observed clinically. Reasons for the difference in pharmacokinetic profile between Gla-100 and Gla-300 are not known, but may be due to factors inherent to the retarding principle of the insulin glargine molecule and a phenomenon of surface-dependent release.4 5 Gla-300 has a pH of approximately 4, at which it is completely soluble; however, once injected subcutaneously, the solution is neutralised and forms a precipitate allowing for the slow release of small amounts of insulin glargine. It has been suggested that the size (ie, surface area) of the subcutaneous deposit may determine the redissolution rate.51

The finding of a significantly lower rate of nocturnal hypoglycaemia associated with a basal insulin analogue compared with NPH is consistent with previous meta-analyses. For example, a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials comparing long-acting basal insulin analogues (Gla-100 or detemir) with NPH showed that, among 10 studies reporting data for nocturnal hypoglycaemia, both analogues were associated with a reduced risk of nocturnal events, with an OR of 0.46 (95% CI 0.38 to 0.55) compared with NPH.52 Similarly, in the pivotal Treat-to-Target study comparing Gla-100 to NPH, the risk reduction with Gla-100 ranged from 42% to 48% for different categories of nocturnal hypoglycaemic events.26 A subsequent meta-analysis of individual patient data from 5 randomised clinical trials comparing Gla-100 to NPH, reported reductions of approximately 50% in nocturnal hypoglycaemia with Gla-100.53 Given these data, along with patient-level data from the EDITION trials,6–8 which when pooled54 demonstrated a 31% lower relative difference in the annualised rate of nocturnal events over the 6-month study period for Gla-300 compared with Gla-100, the even more pronounced difference in the rate of nocturnal events between Gla-300 and NPH in this NMA is expected.

The finding of fewer nocturnal hypoglycaemic events with Gla-300 compared with premixed insulin in this NMA is in line with ‘real-world’ data from the Cardiovascular Risk Evaluation in people with type 2 Diabetes on Insulin Therapy (CREDIT) study, an international observational study that provided insights on outcomes following insulin initiation in clinical practice.55 In CREDIT study, propensity-matched groups were evaluated 1 year after initiating insulin treatment and showed that basal insulin was associated with significantly lower rates of nocturnal hypoglycaemia compared with premixed insulin. This also held true for propensity-matched analysis of basal plus mealtime insulin versus premixed insulin groups.

The substantially lower risk of nocturnal hypoglycaemia associated with Gla-300 is an important finding given the clinical burden associated with such events.56 In a multination survey of 2108 patients with diabetes (types 1 and 2) who had recently experienced nocturnal hypoglycaemia, patients reported a negative impact on their sleep quality as well as their functioning, the day after a nocturnal hypoglycaemic event.57 Nocturnal events were associated with increased self-monitoring of blood glucose, and approximately 15% of patients reported temporary reductions in insulin dose. An economic evaluation of these data found that nocturnal hypoglycaemic events were associated with lost work productivity and increased healthcare utilisation.58 Utilisation costs were estimated to be higher among patients who injured themselves due to a trip or fall associated with their nocturnal hypoglycaemia episode (approximately $2000 per person annually).

While the findings of this NMA are promising for Gla-300, several limitations are evident. The studies included in this NMA were of open-label design, which is inherently subject to bias; however, this type of methodology is typically used in trials comparing insulin therapies due to visible differences between insulin products and/or differences in injection devices. A potential issue is that there was no multiplicity adjustment, and given that there were multiple comparisons, it is possible that positive findings were due to chance. In addition, trial-level summary data may not have been adequately powered to detect differences between products—for example, while randomised controlled studies of Gla-100 versus Gla-300 and pooled patient level data from these studies have shown that Gla-300 is associated with a significantly lower rate of nocturnal hypoglycaemia, the trial-level data comparisons in this NMA did not achieve significance for this end point. Finally, a well-recognised limitation of any NMA is that, by design, these are not randomised comparisons; however, these data can aid the decision-making process until prospective randomised comparative clinical trial data become available.

Strengths of the current NMA include that it was conducted in accordance with established NICE guidelines and that the estimates reported are in line with those in previous meta-analyses of comparative basal insulin studies.52 53 59 60 NMA provides the capability of considering different pathways simultaneously rather than simple indirect pairwise comparison through multiple pathways. Another strength is the quality of studies included in the NMA (ie, the majority had discontinuation rates <20%). The studies included were similar in design and, from a clinical standpoint, heterogeneity of the patient population was not considered an issue. Results of the NMA were internally consistent with what was reported in individual RCTs. Finally, extensive sensitivity analyses considering subsets of studies, different hypoglycaemia definitions and adjusting for trial-level characteristics, supported the robustness of the findings.

In conclusion, clinical trial findings and the results from this NMA suggest that Gla-300 in the treatment of T2DM is associated with a lower rate of nocturnal hypoglycaemia than treatment with premixed insulin and NPH, while demonstrating comparable glycaemic control versus all comparators. Change in body weight was significantly lower for Gla-300 versus premixed insulin, and comparable with other basal insulin. These NMA data, along with randomised clinical trial findings of reduced nocturnal hypoglycaemia and comparable clinical benefits for Gla-300 versus Gla-100, suggest that this new basal insulin represents an important advance in insulin treatment for patients with T2DM.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Keith Betts, Ed Tuttle, Simeng Han, Jinlin Song, Alice Zhang and Joseph Damron, from the Analysis Group, for study analysis support, and Kulvinder K Singh, PharmD, for medical writing support.

Footnotes

Contributors: NF, EC, CF and AV conceived and designed the study. NF, EC, CF, DZ, WL, AV, HW, H-wC, QZ, EW and CG contributed to the draft of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Sanofi sponsored the NMA.

Competing interests: NF reports personal fees from Sanofi Aventis, during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, outside the submitted work. EC and HW are employees of Sanofi. CF, DZ and EW report grants from Sanofi, during the conduct of the study; and the Employer (Analysis Group) has received other grants from Sanofi to fund other research (eg, in different therapeutic areas); the Employer has similar arrangements with other drug and medical device manufacturers. WL received honoraria and compensation for travel and accommodation costs for attending advisory boards from Sanofi Aventis. AV is an employee of Sanofi and owner of Sanofi shares. QZ is a former employee of Sanofi, and owner of Sanofi shares. CG is a former employee of Sanofi.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas: sixth edition. http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas (accessed 21 Mar 2014).

- 2.World Health Organization. Diabetes Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/ (accessed 1 May 2015).

- 3.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38:140–9. 10.2337/dc14-2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiramoto M, Eto T, Irie S et al. Single-dose new insulin glargine 300 U/ml provides prolonged, stable glycaemic control in Japanese and European people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015;17:254–60. 10.1111/dom.12415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinstraesser A, Schmidt R, Bergmann K et al. Investigational new insulin glargine 300 U/ml has the same metabolism as insulin glargine 100 U/ml. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014;16:873–6. 10.1111/dom.12283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riddle MC, Bolli GB, Ziemen M et al. , EDITION 1 Study Investigators. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using basal and mealtime insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 1). Diabetes Care 2014;37:2755–62. 10.2337/dc14-0991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yki-Järvinen H, Bergenstal R, Ziemen M et al. , EDITION 2 Study Investigators. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using oral agents andbasal insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6-month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 2). Diabetes Care 2014;37:3235–43. 10.2337/dc14-0990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolli GB, Riddle MC, Bergenstal RM et al. , on behalf of the EDITION 3 study investigators. New insulin glargine 300 U/mL compared with glargine 100 U/mL ininsulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes on oral glucose-lowering drugs: a randomized controlled trial (EDITION 3). Diabetes Obes Metab 2015;17:386–94. 10.1111/dom.12438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Evidence SynthesisTechnical Support Documents. http://www.nicedsu.org.uk/evidence-synthesis-tsd-series%282391675%29.htm (accessed 1 May 2015).

- 10.Aschner P, Sethi B, Gomez-Peralta F et al. Glargine vs. premixed insulin for management of type 2 diabetes patients failing oral antidiabetic drugs: the GALAPAGOS study. Barcelona: EASD, 2013:49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buse JB, Wolffenbuttel BH, Herman WH et al. DURAbility of basal versus lispro mix 75/25 insulin efficacy (DURABLE) trial 24-week results: safety and efficacy of insulin lispro mix 75/25 versus insulin glargine added to oral antihyperglycemic drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1007–13. 10.2337/dc08-2117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritsche A, Larbig M, Owens D et al. Comparison between a basal-bolus and a premixed insulin regimen in individuals with type 2 diabetes-results of the GINGER study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010;12:115–23. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain SM, Mao X, Escalante-Pulido M et al. Prandial-basal insulin regimens plus oral antihyperglycaemic agents to improve mealtime glycaemia: initiate and progressively advance insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010;12:967–75. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01287.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kann PH, Wascher T, Zackova V et al. Starting insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: twice-daily biphasic insulin Aspart 30 plus metformin versus once-daily insulin glargine plus glimepiride. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2006;114:527–32. 10.1055/s-2006-949655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazda C, Hulstrunk H, Helsberg K et al. Prandial insulin substitution with insulin lispro or insulin lispro mid mixture vs. basal therapy with insulin glargine: a randomized controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes beginning insulin therapy. J Diabetes Complicat 2006;20:145–52. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ligthelm RJ, Gylvin T, DeLuzio T et al. A comparison of twice-daily biphasic insulin aspart 70/30 and once-daily insulin glargine in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled on basal insulin and oral therapy: a randomized, open-label study. Endocr Pract 2011;17:41–50. 10.4158/EP10079.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raskin P, Allen E, Hollander P et al. Initiating insulin therapy in type 2 Diabetes: a comparison of biphasic and basal insulin analogs. Diabetes Care 2005;28:260–5. 10.2337/diacare.28.2.260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riddle MC, Vlajnic A, Jones B et al. Comparison of 3 intensified insulin regimens added to oral therapy for type 2 diabetes: twice-daily aspart premixed vs glargine plus 1 prandial glulisine or stepwise addition of glulisine to glargine. Diabetes 2011;60(Suppl 1):A113. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins DC, Beisswenger PJ, Ceriello A et al. Mealtime 50/50 basal + prandial insulin analogue mixture with a basal insulin analogue, both plus metformin, in the achievement of target HbA1c and pre- and postprandial blood glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a multinational, 24-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group comparison. Clin Ther 2007;29:2349–64. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenstock J, Ahmann AJ, Colon G et al. Advancing insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes previously treated with glargine plus oral agents: prandial premixed (insulin lispro protamine suspension/lispro) versus basal/bolus (glargine/lispro) therapy. Diabetes Care 2008;31:20–5. 10.2337/dc07-1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strojek K, Bebakar WMW, Khutsoane DT et al. Once-daily initiation with biphasic insulin aspart 30 versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with oral drugs: an open-label, multinational RCT. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:2887–94. 10.1185/03007990903354674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tinahones FJ, Gross JL, Onaca A et al. Insulin lispro mix 25/75 twice daily (LM25) vs basal insulin glargine once daily and prandial insulin lispro once daily (BP) in type 2 diabetes: insulin intensification Barcelona: EASD, 2013:49. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vora J, Cohen N, Evans M et al. Glycemic control and treatment satisfaction in type 2 diabetes: basal plus compared with biphasic insulin in the LANSCAPE trial. Barcelona: EASD, 2013:49. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritsche A, Schweitzer MA, Haring H-U et al. Glimepiride combined with morning insulin glargine, bedtime neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin, or bedtime insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:952–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-12-200306170-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massi Benedetti M, Humburg E, Dressler A et al. A one-year, randomised, multicentre trial comparing insulin glargine with NPH insulin in combination with oral agents in patients with type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res 2003;35:189–96. 10.1055/s-2003-39080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J. Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators. The treat-to-target trial: randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2003;26:3080–6. 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenstock J, Schwartz SL, Clark CM Jr et al. Basal insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: 28-week comparison of insulin glargine (HOE 901) and NPH insulin. Diabetes Care 2001;24:631–6. 10.2337/diacare.24.4.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenstock J, Fonseca V, McGill JB et al. Similar progression of diabetic retinopathy with insulin glargine and neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a long-term, randomised, open-label study. Diabetologia 2009;52:1778–88. 10.1007/s00125-009-1415-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yki-Järvinen H, Kauppinen-Makelin R, Tiikkainen M et al. Insulin glargine or NPH combined with metformin in type 2 diabetes: the LANMET study. Diabetologia 2006;49:442–51. 10.1007/s00125-005-0132-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garber AJ, King AB, Del Prato S et al. Insulin degludec, an ultra-long acting basal insulin, versus insulin glargine in basal-bolus treatment with mealtime insulin aspart in type 2 diabetes (BEGIN Basal-Bolus Type 2): a phase 3, randomised, open-label, treat-to-target non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012;379:1498–507. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60205-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gough SC, Bhargava A, Jain R et al. Low-volume insulin degludec 200 units/ml once daily improves glycemic control similarly to insulin glargine with a low risk of hypoglycemia in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a 26-week, randomized, controlled, multinational, treat-to-target trial: the BEGIN LOW VOLUME trial. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2536–42. 10.2337/dc12-2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meneghini L, Atkin SL, Gough SCL et al. The efficacy and safety of insulin degludec given in variable once-daily dosing intervals compared with insulin glargine and insulin degludec dosed at the same time daily: a 26-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group, treat-to-target trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013;36:858–64. 10.2337/dc12-1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zinman B, Philis-Tsimikas A, Cariou B et al. Insulin degludec versus insulin glargine in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a 1-year, randomized, treat-to-target trial (BEGIN Once Long). Diabetes Care 2012;35:2464–71. 10.2337/dc12-1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zinman B, DeVries JH, Bode B et al. Efficacy and safety of insulin degludec three times a week versus insulin glargine once a day in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: results of two phase 3, 26 week, randomised, open-label, treat-to-target, non-inferiority trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2013;1:123–31. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70013-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollander P, Cooper J, Bregnhoj J et al. A 52-week, multinational, open-label, parallel-group, noninferiority, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with insulin glargine in a basal-bolus regimen with mealtime insulin aspart in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther 2008;30:1976–87. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meneghini L, Kesavadev J, Demissie M et al. Once-daily initiation of basal insulin as add-on to metformin: a 26-week, randomized, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013;15:729–36. 10.1111/dom.12083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raskin P, Gylvin T, Weng W et al. Comparison of insulin detemir and insulin glargine using a basal-bolus regimen in a randomized, controlled clinical study in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2009;25:542–8. 10.1002/dmrr.989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenstock J, Davies M, Home PD et al. A randomised, 52-week, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with insulin glargine when administered as add-on to glucose-lowering drugs in insulin-naive people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2008;51:408–16. 10.1007/s00125-007-0911-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swinnen SG, Dain MP, Aronson R et al. A 24-week, randomized, treat-to-target trial comparing initiation of insulin glargine once-daily with insulin detemir twice-daily in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral glucose-lowering drugs. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1176–8. 10.2337/dc09-2294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holman RR, Thorne KI, Farmer AJ et al. Addition of biphasic, prandial, or basal insulin to oral therapy in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1716–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa075392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liebl A, Prager R, Binz K et al. , PREFER Study Group. Comparison of insulin analogue regimens in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the PREFER Study: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009;11:45–52. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00915.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haak T, Tiengo A, Draeger E et al. Lower within-subject variability of fasting blood glucose and reduced weight gain with insulin detemir compared to NPH insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2005;7:56–64. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00373.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hermansen K, Davies M, Derezinski T et al. A 26-week, randomized, parallel, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with NPH insulin as add-on therapy to oral glucose-lowering drugs in insulin-naive people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1269–74. 10.2337/dc05-1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montañana CF, Herrero CH, Fernandez MR. Less weight gain and hypoglycaemia with once-daily insulin detemir than NPH insulin in intensification of insulin therapy in overweight type 2 diabetes patients: the PREDICTIVE BMI clinical trial. Diabet Med 2008;25:916–23. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02483.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Philis-Tsimikas A, Charpentier G, Clauson P et al. Comparison of once-daily insulin detemir with NPH insulin added to a regimen of oral antidiabetic drugs in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther 2006;28:1569–81. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raslová K, Bogoev M, Raz I et al. Insulin detemir and insulin aspart: a promising basal-bolus regimen for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2004;66:193–201. 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janka H, Plewe G, Riddle M et al. Comparison of basal insulin added to oral agents versus twice-daily premixed insulin as initial insulin therapy for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:254–9. 10.2337/diacare.28.2.254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee LJ, Fahrbach JL, Nelson LM et al. Effects of insulin initiation on patient-reported outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from the durable trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;89:157–66. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raskin PR, Hollander PA, Lewin A et al. Basal insulin or premix analogue therapy in type 2 diabetes patients. Eur J Intern Med 2007;18:56–62. 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yki-Järvinen H, Dressler A, Ziemen M, HOE 901/300s Study Group. Less nocturnalhypoglycemia and better post-dinner glucose control with bedtime insulin glargine compared with bedtime NPH insulin during insulin combination therapy in type 2 diabetes. HOE 901/3002 Study Group. Diabetes Care 2000;23:1130–6. 10.2337/diacare.23.8.1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Becker RH, Dahmen R, Bergmann K et al. New insulinglargine 300 Units mL-1 provides a more even activity profile and prolongedglycemic control at steady state compared with insulin glargine 100 Units mL-1. Diabetes Care 2015; 38:637–43. 10.2337/dc14-0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monami M, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH human insulin in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;81:184–9. 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Home PD, Fritsche A, Schinzel S et al. Meta-analysis of individual patient data to assess the risk of hypoglycaemia in people with type 2 diabetes using NPH insulin or insulin glargine. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010;12:772–9. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ritzel R, Roussel R, Bolli GB et al. Patient-level meta-analysis of the EDITION 1, 2 and 3 studies: glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia with new insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus glargine 100 U/ml in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015;17:859–67. 10.1111/dom.12485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freemantle N, Balkau B, Home PD. A propensity score matched comparison of different insulin regimens 1 year after beginning insulin in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013;15:1120–7. 10.1111/dom.12147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edelman SV, Blose JS. The impact of nocturnal hypoglycemia on clinical and cost-related issues in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2014;40:269–79. 10.1177/0145721714529608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brod M, Wolden M, Christensen T et al. A nine country study of the burden of non-severe nocturnal hypoglycaemic events on diabetes management and daily function. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013;15:546–57. 10.1111/dom.12070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brod M, Wolden M, Christensen T et al. Understanding the economic burden of nonsevere nocturnal hypoglycemic events: impact on work productivity, disease management, and resource utilization. Value Health 2013;16:1140–9. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodbard HW, Gough S, Lane W et al. Reduced risk of hypoglycemia with insulin degludec versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes requiring high doses of Basal insulin: a meta-analysis of 5 randomized begin trials. Endocr Pract 2014;20:285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rys P, Wojciechowski P, Rogoz-Sitek A et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing efficacy and safety outcomes of insulin glargine with NPH insulin, premixed insulin preparations or with insulin detemir in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 2015;52:649–62. 10.1007/s00592-014-0698-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]