Abstract

Objectives

Authors may choose to work with professional medical writers when writing up their research for publication. We examined the relationship between medical writing support and the quality and timeliness of reporting of the results of randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Study sample

Primary reports of RCTs published in BioMed Central journals from 2000 to 16 July 2014, subdivided into those with medical writing support (n=110) and those without medical writing support (n=123).

Main outcome measures

Proportion of items that were completely reported from a predefined subset of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist (12 items known to be commonly poorly reported), overall acceptance time (from manuscript submission to editorial acceptance) and quality of written English as assessed by peer reviewers. The effect of funding source and publication year was examined.

Results

The number of articles that completely reported at least 50% of the CONSORT items assessed was higher for those with declared medical writing support (39.1% (43/110 articles); 95% CI 29.9% to 48.9%) than for those without (21.1% (26/123 articles); 95% CI 14.3% to 29.4%). Articles with declared medical writing support were more likely than articles without such support to have acceptable written English (81.1% (43/53 articles); 95% CI 67.6% to 90.1% vs 47.9% (23/48 articles); 95% CI 33.5% to 62.7%). The median time of overall acceptance was longer for articles with declared medical writing support than for those without (167 days (IQR 114.5–231 days) vs 136 days (IQR 77–193 days)).

Conclusions

In this sample of open-access journals, declared professional medical writing support was associated with more complete reporting of clinical trial results and higher quality of written English. Medical writing support may play an important role in raising the quality of clinical trial reporting.

Keywords: Randomised controlled trials, CONSORT, Medical writing, Quality, Peer review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First study to examine the value that professional medical writing support brings to manuscript development across a broad range of journals.

Used robust methodology and objective measures to assess systematically the quality of reporting of randomised controlled trials in BioMed Central journals.

In this observational study, the characteristics of the two groups of articles differed in some respects, in addition to the involvement of medical writing support.

Available measurements of timeliness may not correspond to the steps in the manuscript submission process that are the responsibility of professional medical writers.

Articles that met the inclusion criteria were from 74 different journals, but it remains to be seen whether the findings are applicable to journals other than those published by BioMed Central.

Introduction

Publication in a peer-reviewed journal remains the gold standard for disclosing clinical study results, but it has been estimated that only about half of biomedical research is published in full, and failure to publish is associated with negative study findings.1 The pharmaceutical industry in particular has been criticised for incomplete reporting of clinical studies.2 The complete and transparent reporting of clinical studies is important to allow others to appraise and interpret the results fully.3 Researchers and clinicians can misjudge the benefits or risks of therapies when study details are not fully disclosed.

Reporting guidelines provide advice on how to disclose research methods and findings.4 The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist describes the information that should be included when reporting randomised studies.5 Although the adoption of the CONSORT checklist by journals has improved the reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), adherence to reporting guidelines remains suboptimal.6 7 In particular, details of the prespecified primary outcomes, sample size calculation, randomisation, and allocation concealment are often inadequately disclosed, leaving the reader unable to confirm whether the studies were adequately planned and conducted.6 8

Clinicians understand the importance of disseminating research findings but report lack of time as a major barrier to doing so.9–11 Authors may enlist the help of professional medical writers, who do not usually meet the criteria for authorship of the article.12 Such work is undertaken under the direction of the study authors and is subject to strict guidelines.13 14 Medical writing is not ghostwriting, which occurs when writing contributions are not disclosed in a manuscript.15 Given the size of the biomedical literature and an estimated prevalence of professional medical writing support of 6–11%,16 17 it is perhaps surprising that few studies have evaluated the impact of professional medical writing support on the quality and speed of scientific reporting. In this cross-sectional study, we aimed to examine the relationship between declared medical writing support and the quality and timeliness of articles reporting RCTs. Timeliness of acceptance was measured by the time between manuscript submission and editorial acceptance by the journal; manuscript preparation time was not assessed.

Methods

Sample selection

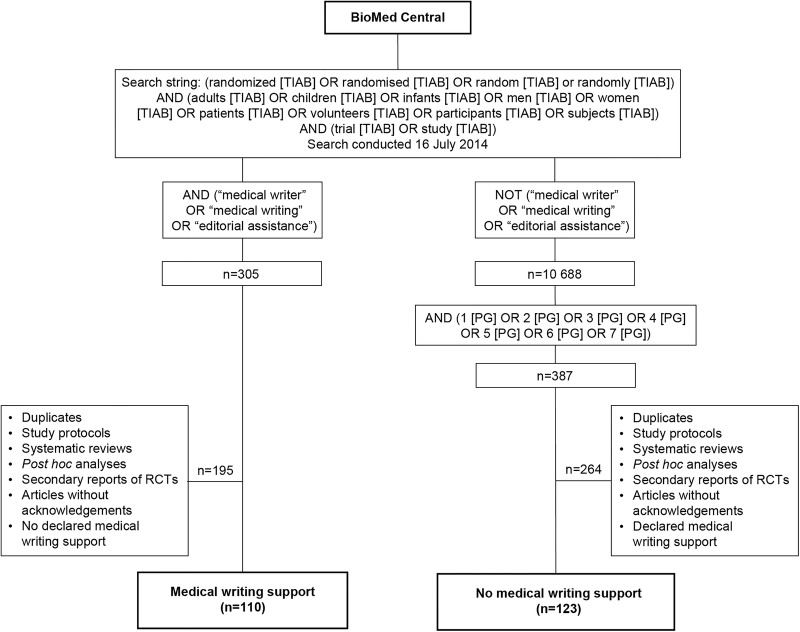

We examined the reporting of the results of RCTs of pharmacological interventions published in BioMed Central journals (text box). A pilot study in other journals yielded an insufficiently large sample of articles with declared medical writing support. BioMed Central journals endorse the CONSORT statement and have been used in previous studies of adherence to the CONSORT guidelines.18 We conducted a search on 16 July 2014 using the BioMed Central website19 to identify articles that described the results of RCTs. No limits were set for the year of article publication. The search terms used are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the study design. The terms TIAB and PG allow searches to be specified on the basis of title/abstract and article page number, respectively. RCTs, randomised controlled trials.

We divided the articles reporting the results of RCTs into two groups according to whether or not they acknowledged the support of professional medical writers. Articles with declared medical writing support were identified using the search terms ‘medical writer’, ‘medical writing’ and ‘editorial assistance’ (figure 1). The remaining articles were identified as the group without declared medical writing support. To reduce the size of this group in a systematic, unbiased way, articles were selected on the basis of their page number. (In BioMed Central journals, each article is assigned a single page number.) Test searches showed that restricting the page numbers to 1–7 would yield a similar number of articles to that in the group with declared medical writing support.

Eligibility criteria

All primary reports of parallel-group, randomised trials of pharmacological and food supplement interventions were included. Full articles were reviewed and the presence or absence of declared medical writing support was confirmed. Articles without acknowledgements were excluded. Duplicates, reviews, post hoc analyses and study protocols were also excluded. For the purpose of data collection, the two groups of articles were then combined and sorted alphabetically by title.

Data extraction

The published version of each article was evaluated. We assessed the completeness of reporting of RCTs by scoring articles using a subset of 12 items from the 2010 CONSORT checklist5 that have previously been shown to be poorly reported.6 20 Methodological details analysed were the specification of the primary outcome (item 6a), sample size calculation (item 7a), method of generating the random allocation sequence (item 8a), type of randomisation (item 8b), mechanism to implement the allocation sequence (item 9), who generated the allocation sequence (item 10), who was blinded (item 11a), and description of the similarity of interventions (item 11b) (see online supplementary table S1). The other items that we examined were the publication of a participant flow diagram (item 13), dates defining recruitment and follow-up periods (item 14a), details of trial registration (item 23), and access to the study protocol (item 24). For each article, inclusion of these 12 CONSORT checklist items was assessed independently by two reviewers who were blinded to the objectives of the study. Each item was rated as being completely described, incompletely described, absent or not applicable. In cases in which there was a discrepancy in the rating, a third reviewer adjudicated.

For overall acceptance time, we extracted the dates of article submission and editorial acceptance. When prepublication history was available, data were obtained for the time taken for completion of the first round of peer review and for submission of the response to reviewers. Data were also extracted for the quality of written English, as assessed by peer review: the BMC-series journals ask reviewers to rate the quality of written English as ‘Acceptable’, ‘Needs some language corrections before being published’ or ‘Not suitable for publication unless extensively revised’.

We classified articles according to the funding source, as stated in the acknowledgements, competing interests, or disclosures section of the manuscripts. Studies were classified as industry funded if this was declared in the article, or if one or more authors had an affiliation with the pharmaceutical industry or other commercial organisation. Articles were classified as part-industry funded if this was stated or if a commercial organisation supplied the study treatment but was not otherwise involved in the study.

Data analysis

To assess the association of adherence to CONSORT guidelines with declared medical writing support, a relative risk (RR) was calculated with 95% CIs for each of the 12 selected CONSORT items, dichotomised as completely described versus not completely described (incompletely described or absent). Ratings that were not applicable were not included in the analysis. Many articles with medical writing support are funded by industry; hence, a subanalysis was conducted to examine the association of medical writing support with the reporting quality of industry-sponsored studies. Logistic regression was conducted with medical writing support as the independent variable, complete description of at least 50% of the items as the dependent variable and year as a covariable. No formal sample size or power calculation was performed: the size of the study was determined by the number of articles with medical writing support in the study sample. Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA (V.13). Medians and IQRs were calculated using Microsoft Excel.

About BioMed Central.

Founded in 2000, BioMed Central is the largest open-access science publisher.

BioMed Central publishes over 290 peer-reviewed journals, which span many areas of biology and medicine, with impact factors ranging from 0.4 to 10.5.

To date, approximately 250 000 articles have been published by BioMed Central.

For some BioMed Central journals, prepublication history is available, including peer reviewers’ comments and the dates of submission, peer review and editorial acceptance.

Results

Characteristics of the articles assessed

Our initial electronic search identified 305 potentially relevant articles reporting the results of RCTs with declared medical writing support (figure 1). Following manual review, 110 articles from 44 different journals were confirmed as eligible for inclusion in the group of articles with medical writing support. The distribution of the search terms used to identify medical writing support was: ‘medical writer’ (12.7%); ‘medical writing’ (43.6%); ‘editorial assistance’ (21.8%) and ‘medical writing’ and ‘editorial assistance’ (21.8%). There were 10 688 potentially relevant articles without declared medical writing support; after filtering on page number, 387 articles remained. After manual review, 123 articles from 57 different journals met the eligibility criteria for inclusion as RCT reports without declared medical writing support. For both groups, most of the excluded publications were study protocols or secondary reports of RCTs. Overall, articles that met the inclusion criteria were from 74 different journals.

Articles with declared medical writing support described studies with a higher median number of randomised patients than articles without this support (159 patients (IQR 65.75–407.75 patients) vs 43 patients (IQR 21–82 patients)) (table 1). Almost all articles with declared medical writing support were industry funded (98.2%). In contrast, only 31.7% of articles without medical writing support were funded by industry. The first identified article without declared medical writing support was published in 2001. The first article with declared medical writing support was published in 2005, and there was an increase in the number of declared medical writing support over the study period (see online supplementary figure S1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the included studies

| Medical writing support (n=110) | No medical writing support (n=123) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of journals that articles were published in | 44 | 57 |

| Number of authors, median (IQR) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (4–8) |

| Articles published on behalf of a study group | 12 (10.9%) | 4 (3.3%) |

| Number of patients randomised to study, median (IQR) | 159 (65.75–407.75) | 43 (21–82) |

| Year of publication | ||

| 2001–2004 | 0 | 17 (13.8%) |

| 2005–2007 | 12 (10.9%) | 25 (20.3%) |

| 2008–2010 | 31 (28.2%) | 34 (27.6%) |

| 2011–2014 | 67 (60.9%) | 47 (38.2%) |

| Funding source | ||

| Industry | 108 (98.2%) | 39 (31.7%) |

| Part-industry | 2 (1.8%) | 23 (18.7%) |

| Non-industry | 0 | 61 (49.6%) |

Completeness of reporting

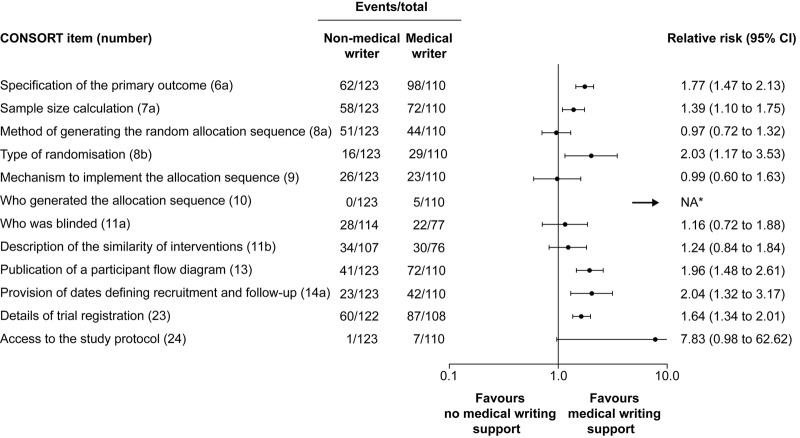

For 6 of the 12 CONSORT items assessed, a higher rate of complete reporting was observed in articles with acknowledged medical writing support than in those without (figure 2). These were specification of the primary outcome (RR 1.77; 95% CI 1.47 to 2.13), sample size calculation (RR 1.39; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.75), type of randomisation (RR 2.03; 95% CI 1.17 to 3.53), publication of a participant flow diagram (RR 1.96; 95% CI 1.48 to 2.61), provision of dates defining recruitment and follow-up (RR 2.04; 95% CI 1.32 to 3.17), and details of trial registration (RR 1.64; 95% CI 1.34 to 2.01). RR could not be calculated for item 10 (who generated the allocation sequence) because it was fully described only in articles with acknowledged medical writing support. For the other five items, there was no association between medical writing support and completeness of reporting.

Figure 2.

Differences in the reporting of CONSORT items between articles with and without acknowledged medical writing support. *Relative risk could not be calculated for item 10 because all articles in the group without acknowledged medical writing support were assessed as having been incompletely described. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; NA, not applicable.

A sensitivity analysis for completeness of reporting is shown in online supplementary table S2. The proportion of articles that completely reported at least 50% of the CONSORT items assessed was higher for those with declared medical writing support than for those without declared medical writing support (39.1% (43/110 articles); 95% CI 29.9% to 48.9% vs 21.1% (26/123 articles); 95% CI 14.3% to 29.4%). In the subanalysis looking at industry-funded articles, those with declared medical writing support were more than twice as likely as those without declared medical writing support to report at least 50% of studied items completely (38.0% (41/108 articles); 95% CI 28.9% to 47.8% vs 17.9% (7/39 articles); 95% CI 8.1% to 34.1%). When looking at articles without acknowledged medical writing support, there was no association between funding source and the completeness of reporting.

A logistic regression analysis showed that year of publication was associated with quality of reporting (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.06 to 1.32). Thus, the odds of reporting at least 50% of items completely increased every year by 18%. Taking into account publication year, the OR of reporting at least 50% of CONSORT items completely for articles with declared medical writing support was 1.88 (95% CI 1.03 to 3.42). Online supplementary figure S2 shows the mean proportion of complete items stratified by year of publication and the presence or absence of medical writing support. For each year, the mean proportion of completely reported items was higher for articles with medical writing support than for those without.

Quality of written English

Articles with declared medical writing support were more likely than those without to have been rated by all the reviewers as having acceptable written English during peer review (81.1% (43/53 articles); 95% CI 67.6% to 90.1% vs 47.9% (23/48 articles); 95% CI 33.5% to 62.7%). The proportion of articles with the corresponding author having an affiliation from a country where English was the first language was similar for both groups: 49.1% and 50.4%, respectively, for articles with and without medical writing support.

Time from manuscript submission to editorial acceptance

Overall, the median acceptance time was 31 days longer for articles with declared medical writing support than for those without (167 days (IQR 114.5–231 days) vs 136 days (IQR 77–193 days)). For both study groups, the median number of versions submitted was three. Considering the subgroup of industry-funded studies with and without declared medical writing support (n=107 and n=39 articles, respectively), those with declared medical writing support had a longer median acceptance time than those without (169 days (IQR 113–232 days) vs 104 days (IQR 77–180 days)).

To identify possible reasons for this delay in acceptance, the time taken for different steps in manuscript processing was analysed for articles with this information. Median time from submission to completion of peer review and median time to respond to reviewers were longer for articles with medical writing support than for those without (see online supplementary table S3). The time from response to reviewers to editorial acceptance was similar for both groups of articles. This pattern remained when the analysis was restricted to industry-funded articles (see online supplementary table S4).

Discussion

Declared professional medical writing support was associated with improved completeness of reporting in our observational study of reports of RCTs published in a series of open-access journals between 2000 and 2014. In the absence of declared medical writing support, there was no difference in the completeness of reporting between articles reporting industry-funded trials and non-industry-funded and part-industry-funded trials. Completeness of reporting was enhanced across a range of important items from the CONSORT checklist, including the specification of the primary outcome, and details of the sample size calculation and randomisation. The complete reporting of the design and conduct of clinical studies is at the heart of evidence-based medicine. The effects of interventions can be exaggerated or underestimated in studies with poor methodology, and researchers can assess the likelihood of bias only if the methods and results are completely reported.21 22 Articles with declared medical writing support were also associated with better quality of written English than those without. There are sound reasons to believe that the involvement of professional medical writers improves the overall quality of articles. Medical writers specialise in developing peer-reviewed manuscripts and other scientific documents, and commonly receive training in Good Publication Practice.23

The findings of our study also suggest that overall compliance with CONSORT guidelines is lacking. Even with professional medical writing support, fewer than half of the articles reported at least 50% of studied CONSORT items completely. As well as authors, both peer reviewers and journal editors have a responsibility for ensuring that articles adhere to reporting guidelines. However, peer reviewers often fail to notice important deficiencies in the reporting of RCTs.18 In fact, they may not understand the importance of checking the compliance of articles with CONSORT guidelines, possibly as a result of insufficiently explicit instructions regarding their role.24 From our own experience, checking an article for compliance with the full CONSORT checklist would take approximately 1 h. We would recommend that this is a specialised task that could be undertaken by journal editors, or even by professional medical writers.

This study looked at the quality of published articles in a real-life situation. No limit was set on the year of article publication, although the study is limited by the date of inception of BioMed Central (2000). Since this was not a randomised study, the characteristics of the two groups of articles differ in some respects, in addition to the involvement of medical writing support. The key differences between the two groups of articles were that those with declared medical writing support were almost exclusively sponsored by industry and were published more recently than those written without medical writing support. However, it seems unlikely that the results of this study can be attributed to these differences between the two groups of articles. Thus, in the subset of industry-funded trials, completeness of reporting was even more strongly associated with medical writing support. Furthermore, for each year of publication, the mean proportion of complete items was higher for articles with medical writing support than for those without. Articles with declared medical writing support were associated with a slightly longer overall acceptance time than articles without this support. One limitation of this assessment is that the measure of timeliness may not correspond to steps in the submission process that are the responsibility of the medical writer. The delay in overall acceptance was attributable to the additional time taken for peer review and for the authors to respond to reviewers. Articles that declared medical writing support tended to describe larger trials than those without, and had more authors, suggesting that these articles may have reported more complex research and therefore taken longer to review or, possibly, underwent greater scrutiny by peer reviewers. Likewise, queries from peer reviewers may be more complicated for articles with medical writing support than for those without.

Our findings are based on the assumption that the enhanced quality of reporting observed can be attributed to medical writing support. It was not possible to discount the influence of some potential confounding factors, such as the expertise of the authors of the article (eg, the presence of a statistician) or the quality of the clinical study report available. However, medical writers generally are more familiar with publication guidelines than investigators,12 and their role would normally include ensuring that the manuscript complies with journal submission criteria and compliance with reporting standards. It should also be noted that there are international guidelines regarding the content to be included in clinical study reports25 and, in fact, these documents are usually written by medical writers.

The classification of articles in our study was based on the veracity of the acknowledgement of medical writing support. The importance of acknowledging medical writing support is stated in guidelines on Good Publication Practice and, according to the editorial policy of BioMed Central, medical writing support should be acknowledged explicitly.14 26 Although we cannot rule out the possibility that some articles were written with undeclared writing support, this would tend to underestimate the true differences between the two groups. Finally, the articles that met the inclusion criteria for our study were from 74 different journals, but it remains to be seen whether our findings are applicable to journals other than those published by BioMed Central. The articles included in this study may not be representative of those published in journals that do not endorse the CONSORT checklist (ie, the effect of medical writing support may be increased if authors do not receive guidance from the journal). Conversely, the effect of medical writing support may be reduced in journals that ensure compliance with CONSORT criteria.

A systematic review published in 2003 found that there was insufficient research to assess the effects of professional writing assistance on biomedical publishing.27 Only one other study has evaluated the association of declared medical writing support and the completeness of reporting.20 This analysis was restricted to a single journal in which there were very few non-industry-sponsored studies and the overall completeness of reporting was high; although articles that declared professional medical writers were more likely to comply with the CONSORT criteria, the effect was small. A study of articles published in the Dutch Journal of Medicine found that editing for scientific content and written English, tasks that are often undertaken by medical writers, significantly improved the style and readability of manuscripts.28 It has previously been suggested that, in addition to raising the standard of publications, professional medical writer involvement can speed up the publication process13; however, there is limited evidence to demonstrate the acceleration of manuscript acceptance with medical writing support,29 30 and, in the current study, overall acceptance time was slightly longer in the group with medical writing support.

Clinical trials can help to advance the treatment of patients only if the methods and results are fully disclosed. The reporting of industry-sponsored studies appears to be improving over time,31 and a recent study showed that industry-funded trials were more likely to comply with legal reporting obligations than trials funded by government or academic institutions.32 Our results suggest that the enhanced reporting seen in industry-funded trials may be attributable to professional medical writing support. Even so, when only approximately half of research is published in full and many publications do not disclose important information, much research effort is wasted.33 In fact, it has been proposed that professional medical writing support should be used to address the backlog of unreported clinical study results.34 The results of this study suggest that this support could also improve the quality of RCT reporting. Medical writing support is often funded by industry and, as a result, has sometimes attracted controversy.35 36 There is no place for ghostwriting (ie, the unacknowledged use of medical writers) in manuscript development. According to the results of surveys, the overwhelming majority of authors (84–88%) valued the assistance provided by professional medical writers, in particular in editing manuscripts and ensuring conformity with reporting guidelines such as CONSORT.37 38 Accordingly, the legitimate role that medical writers can play is acknowledged in guidelines on Good Publication Practice.14

Conclusions

There remains a need to improve the quality of reporting of clinical studies. The disclosure of important information regarding clinical studies, which is needed when determining the validity and generalisability of findings, may be enhanced with professional medical writing support.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephen Lang for development of the article ratings and for data extraction, and Rajinder Chawla for data extraction.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Elizabeth Wager at @SideviewLiz; Christopher Winchester at @ChrisW_PharmaG; Richard White at @Richard_PharmaG; and Paul Farrow at @Paul_MedComms

Contributors: WTG and CCW were involved in the design, implementation and analysis of the study, and in the drafting of the manuscript. SH, PF, RW and EW were involved in the design and analysis of the study, and commented on the manuscript. KY conducted the statistical analysis of the study and commented on the manuscript. WTG is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: This study was funded by Oxford PharmaGenesis.

Competing interests: WTG, PF, RW and CCW are medical communication professionals employed by Oxford PharmaGenesis. KY is a former employee of Oxford PharmaGenesis. PF, RW and CCW are shareholders of Oxford PharmaGenesis. CCW holds shares in AstraZeneca and Shire Pharmaceuticals. SH is a member of the CONSORT group. EW is the owner of Sideview, which provides training and consultancy in medical writing, and has previously worked as a medical writer.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The full data set is available on request from the corresponding author (will.gattrell@pharmagenesis.com).

References

- 1.Scherer RW, Langenberg P, von Elm E. Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):MR000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J et al. . Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:MR000033 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altman DG, Simera I. Responsible reporting of health research studies: transparent, complete, accurate and timely. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65:1–3. 10.1093/jac/dkp410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A et al. . Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med 2010;8:24 10.1186/1741-7015-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM et al. . The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed. BMJ 2010;340:c723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A et al. . Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review. Med J Aust 2006;185:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan AW, Altman DG. Epidemiology and reporting of randomised trials published in PubMed journals. Lancet 2005;365:1159–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71879-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smyth RM, Jacoby A, Altman DG et al. . The natural history of conducting and reporting clinical trials: interviews with trialists. Trials 2015;16:16 10.1186/s13063-014-0536-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P et al. . Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 2014;383:267–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherer RW, Ugarte-Gil C, Schmucker C et al. . Authors report lack of time as main reason for unpublished research presented at biomedical conferences: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:803–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norris R, Bowman A, Fagan JM et al. . International Society for Medical Publication Professionals (ISMPP) position statement: the role of the professional medical writer. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:1837–40. 10.1185/030079907X210642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs A, Wager E. European Medical Writers Association (EMWA) guidelines on the role of medical writers in developing peer-reviewed publications. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:317–22. 10.1185/030079905X25578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L et al. , International Society for Medical Publication Professionals. Good Publication Practice for Communicating Company-Sponsored Medical Research: GPP3. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461–4. 10.7326/M15-0288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolley KL, Gertel A, Hamilton CW et al. . Time to finger point or fix? An invitation to join ongoing efforts to promote ethical authorship and other good publication practices. Ann Pharmacother 2013;47:1084–7. 10.1345/aph.1S178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nastasee SA. Acknowledgment of medical writers in medical journal articles: a comparison from the years 2000 and 2007. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:S6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woolley KL, Ely JA, Woolley MJ et al. . Declaration of medical writing assistance in international peer-reviewed publications. JAMA 2006;296:932–4. 10.1001/jama.296.8.932-b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopewell S, Collins GS, Boutron I et al. . Impact of peer review on reports of randomised trials published in open peer review journals: retrospective before and after study. BMJ 2014;349:g4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BioMed Central Advanced Search. 2015. http://www.biomedcentral.com/logon?url=%2Fmy (accessed 11 Dec 2015).

- 20.Jacobs A. Adherence to the CONSORT guideline in papers written by professional medical writers. Write Stuff 2010;19:196–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pildal J, Hróbjartsson A, Jørgensen KJ et al. . Impact of allocation concealment on conclusions drawn from meta-analyses of randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:847–57. 10.1093/ije/dym087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL et al. . Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ 2008;336:601–5. 10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wager E, Woolley K, Adshead V et al. . Awareness and enforcement of guidelines for publishing industry-sponsored medical research among publication professionals: the Global Publication Survey. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004780 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chauvin A, Ravaud P, Baron G et al. . The most important tasks for peer reviewers evaluating a randomized controlled trial are not congruent with the tasks most often requested by journal editors. BMC Med 2015;13:158 10.1186/s12916-015-0395-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports. 1995. http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E3/E3_Guideline.pdf (accessed 11 Dec 2015).

- 26.BioMed Central Editorial Policies. 2015. http://www.biomedcentral.com/about/editorialpolicies (accessed 11 Dec 2015).

- 27.Lagnado M. Professional writing assistance: effects on biomedical publishing. Learn Publ 2003;16:21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierie JP, Walvoort HC, Overbeke AJ. Readers’ evaluation of effect of peer review and editing on quality of articles in the Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. Lancet 1996;348:1480–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05016-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey M. Science editing and its effect on manuscript acceptance time. Am Med Writ Assoc J 2011;26:147–52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolley K, Ely J, Woolley M et al. . Declaration of medical writing assistance in international, peer-reviewed publications and effect of pharmaceutical sponsorship. Presented at the International Congress on Peer Review and Biomedical Publication; 16–18 September 2005. http://www.peerreviewcongress.org/abstracts.html#declaration (accessed 11 Dec 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawal B, Deane BR. Clinical trial transparency update: an assessment of the disclosure of results of company-sponsored trials associated with new medicines approved in Europe in 2012. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:1431–5. 10.1185/03007995.2015.1047749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson ML, Chiswell K, Peterson ED et al. . Compliance with results reporting at ClinicalTrials.gov. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1031–9. 10.1056/NEJMsa1409364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60329-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woolley KL, Gertel A, Hamilton C et al. , Global Alliance of Publication Professionals (GAPP). Poor compliance with reporting research results—we know it's a problem…how do we fix it? Curr Med Res Opin 2012;28:1857–60. 10.1185/03007995.2012.739152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeBakey L, DeBakey S. Ghostwriters: not always what they appear. JAMA 1995;274:870–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldacre B. Medical ghostwriters who build a brand. The Guardian 2010 Sept 18. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/sep/18/bad-science-medical-ghostwriters (accessed 11 Dec 2015).

- 37.Marchington JM, Burd GP. Author attitudes to professional medical writing support. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:2103–8. 10.1185/03007995.2014.939618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Camby I, Delpire V, Rouxhet L et al. . Publication practices and standards: recommendations from GSK Vaccines’ author survey. Trials 2014;15:446 10.1186/1745-6215-15-446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]