Abstract

Objective

This study surveyed all Iraqi medical schools and a cross-section of Iraqi medical students regarding their institutional and student experiences of medical education amidst ongoing conflict. The objective was to better understand the current resources and challenges facing medical schools, and the impacts of conflict on the training landscape and student experience, to provide evidence for further research and policy development.

Setting

Deans of all Iraqi medical schools registered in the World Directory of Medical Schools were invited to participate in a survey electronically. Medical students from three Iraqi medical schools were invited to participate in a survey electronically.

Outcomes

Primary: Student enrolment and graduation statistics; human resources of medical schools; dean perspectives on impact of conflict. Secondary: Medical student perspectives on quality of teaching, welfare and future career intentions.

Findings

Of 24 medical schools listed in the World Directory of Medical Schools, 15 replied to an initial email sent to confirm their contact details, and 8 medical schools responded to our survey, giving a response rate from contactable medical schools of 53% and overall of 33%. Five (63%) medical schools reported medical student educational attainment being impaired or significantly impaired; 4 (50%) felt the quality of training medical schools could offer had been impaired or significantly impaired due to conflict. A total of 197 medical students responded, 62% of whom felt their safety had been threatened due to violent insecurity. The majority (56%) of medical students intended to leave Iraq after graduating.

Conclusions

Medical schools are facing challenges in staff recruitment and adequate resource provision; the majority believe quality of training has suffered as a result. Medical students are experiencing added psychological stress and lower quality of teaching; the majority intend to leave Iraq after graduation.

Keywords: Conflict, War, Medical education, healthcare, Training

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to provide insight into the medical school and student experience in Iraq amidst ongoing conflict.

The method employed is a simple survey providing detailed data to a range of questions.

This survey does not permit a detailed subjective discussion concerning finer considerations of educational policy and has a low response rate.

Introduction

Conflict or violent insecurity remains a persistent international problem. By 2030, almost half of the world's poorest people are predicted to live in countries affected by fragility, conflict and violence.1 The presence of conflict or instability within or between states affects access to ordinary civil activities such as employment, healthcare and education.2–4

The health burden during conflict or violent insecurity is influenced by several interacting ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ factors. Direct factors include injuries sustained through violence and psychological illness such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Indirect factors include other causes of ill-health such as disease and malnutrition resulting from diminished access to or availability of basic healthcare, food, water and sanitation.5 These may be exacerbated by population displacements, damage to healthcare facilities or violence towards personnel, and infrastructural degradation which disrupt logistics and supply chains.6 The collapse of national public health programmes such as maternal care or childhood vaccination further compounds the health burden.6–9

A breakdown in civic activity during violent insecurity can lead to the delay, reduction or cessation of education and training programmes in medicine,4 affecting those still studying, soon to graduate or already in practice.10–12 Given the often significant health needs of conflict-affected populations, a failure to continue training and graduation of medical students in-country represents a double hit: a stagnation or reduction in national medical workforce capacity due to the reduced availability of qualified doctors, who are fluent in regional languages and sensitive to cultural norms; and an economic loss due to the sums of (often public) money invested in their training which have not resulted in medically qualified doctors ready to practise. Given the unmet and frequently escalating health burdens in affected countries, a lack of national medical capacity is on occasion met by overseas assistance, which while well-intentioned may not be sufficient, timely, sustained or as culturally sensitive.13–16

Isolated reports exist on the impact of conflict and violent insecurity on medical education. These conflicts are of varying scale and nature, including interstate and asymmetrical wars. For example, in the USA, the Second World War saw a substantial increase in the volume of medical graduates, with emphasis added on curricula components such as first aid and emergency medicine.17 During the 15-year Lebanese civil-war, educational activities at the American University of Beirut Medical College were at times suspended.18 While in the 2006 Lebanon-Israel war, despite the curtailing of formal education, some medical students were exposed to additional wartime medical challenges and training.19 In the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, buildings of the satellite colleges and hospitals of Zagreb Medical School were significantly damaged; eventually the Osijek branch was closed and students transferred to Zagreb city.10 Medical students were active in preparation of medical supplies and serving on the frontline.11 At the only recognised medical school in Liberia, the civil war stretching over 20 years caused significant delays in medical training due to destruction of college infrastructure and loss of teaching staff.12 Such reports offer testament to the complex challenges faced by medical institutions, their faculty and students in times of conflict or violent insecurity. In Iraq, a series of interventions and crises in recent years have placed Iraqi civil society and educational institutions under significant strain: from the prolonged intellectual embargo,20 2003 invasion21 and—at the time of writing—protracted conflict involving ‘Daesh’ or ‘ISIL’ militants, these events have exerted profound negative effects on societal function.22

The aim of this study was to examine the feasibility of surveying medical schools and medical students in Iraq; identify impacts of the ongoing conflict on medical education; and inform wider multilateral studies seeking to identify pragmatic programme and policy solutions to the issues arising.

Methods

Medical schools

Medical schools in Iraq were identified using the World Directory of Medical Schools database. Emails of medical school deans were collected and deans were invited to complete an online questionnaire survey (GoogleForms) in English (see online supplementary appendix 1). Reminders were sent twice by email over the 3-month data collection period (March–May 2015). The questionnaire asked deans to complete questions relating to: their total number of students, teaching and administrative staff; annual student graduation and enrolment; levels of student dropout and the average cost of training each medical student; whether conflict had affected medical student training or attainment; the impact of conflict on staff recruitment and retention; the effect of conflict on local infrastructure and deans’ perspectives on areas for assistance. The questionnaire was validated in partnership with an Iraqi medical school Professor. Medical school geographical location images were generated using GoogleMaps and are accurate as of August 2015.

Medical students

Owing to the absence of institutional student emails, medical students from three large Iraqi medical schools were invited to participate in English in an online survey (GoogleForms) through medical school online forums and social media (Iraqi Medical Schools, International Federation of Medical Student's Associations, Facebook IFMSA). The questionnaire asked medical students to complete questions relating to: their basic demographics; whether they were a guest or ordinary student; the impact of conflict on their training; whether they were considering dropping out; their academic and welfare concerns; whether their or their peers’ safety was threatened; future career intentions and students’ perspectives on areas for assistance. The questionnaire was validated in partnership with Iraqi medical students (IFMSA Iraq). Full questionnaire details can be found in online supplementary appendix 2.

Data analysis

Anonymised data were collated using GoogleForms, organised in Excel and figures were generated using Adobe Illustrator V.6. Statistical analyses were applied using GraphPad V.5.

Ethical review

Exemption from review was granted by the Ethics Review Board of Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA (see online supplementary appendix 3).

Results

Medical schools

As shown in table 1, Iraq currently has 24 medical schools listed in the World Directory of Medical Schools. Of these, 15 medical schools replied to an initial email sent to confirm their contact details, we were unable to elicit a response from the remaining 9. Of the 15 who replied, 8 medical schools responded to our survey, giving a response rate from contactable medical schools of 53% and overall of 33%. Of the 8 responding medical schools, figure 1 illustrates their geographical location and table 2 details the number of medical students across year groups. As a newly established institution, one of the respondents, Jabir Ibn Hayyan Medical University has only begun enrolling students recently.

Table 1.

Iraqi medical schools and study participants

| Iraq medical schools n=24 | Replied n=15 | Responded n=8 |

|---|---|---|

| Al Nahrain University | N | |

| Al-Anbar University | N | |

| Al-Iraqia University (Ibn Seinna College of Medicine, Iraqi University) | Y | |

| Al-Qadisiya University College of Medicine | N | |

| Babylon University | N | |

| Hawler Medical University | Y | Y |

| Jabir Ibn Hayyan Medical University | Y | Y |

| Kufa University | Y | Y |

| Ninevah College of Medicine | N | |

| Sulaimani College of Medicine | Y | Y |

| University of Al-Mustansiriyah | Y | |

| University of Al-Muthana College of Medicine | Y | Y |

| University of Baghdad | Y | |

| University of Baghdad. Al-Kindy College of Medicine | N | |

| University of Basrah | Y | |

| University of Diyala College of Medicine | Y | Y |

| University of Duhok Faculty of Medical Sciences | N | |

| University of Kerbala College of Medicine | N | |

| University of Kirkuk College of Medicine | Y | |

| University of Misan | Y | |

| University of Mosul College of Medicine | N | |

| University of Thi Qar College of Medicine | Y | |

| University of Tikrit College of Medicine | Y | Y |

| University of Wasit | Y | Y |

The currently listed medical schools in Iraq according to the World Directory of Medical Schools, those which replied to an initial email and those which participated in the study.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of participating medical schools. Image generated using GoogleMaps. (1) Jabir Ibn Hayyan Medical University; (2) University of Tikrit College of Medicine; (3) University of Wasit; (4) Hawler Medical University; (5) University of Diyala College of Medicine; (6) Sulaimani College of Medicine; (7) University of Al-Muthana College of Medicine; (8) Kufa University.

Table 2.

Participating medical school's student population

| Medical school | Number of medical students |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Year 6 | Total ‘14/15 | Δ in total since ‘1223 | |

| Al-Muthana College of Medicine | 67 | 32 | 41 | 57 | 35 | 29 | 261 | 161 |

| Diyala College of Medicine | 60 | 53 | 48 | 64 | 46 | 51 | 322 | 60 |

| Hawler Medical University | 157 | 177 | 188 | 165 | 149 | 151 | 987 | – |

| Jabir Ibn Hayyan Medical University | 100 | 85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185 | – |

| Kufa University | 160 | 138 | 110 | 115 | 150 | 134 | 807 | 156 |

| Sulaimani College of Medicine | 147 | 177 | 167 | 139 | 136 | 103 | 869 | 139 |

| Tikrit College of Medicine | 118 | 106 | 127 | 157 | 113 | 100 | 721 | 310 |

| Wasit | 77 | 54 | 65 | 85 | 76 | 51 | 408 | 123 |

Total student numbers across each year at participant medical schools, and in comparison with previous reports in 2012 from.23 ‘-‘ denotes data that was unavailable.

We collected a range of details from medical schools to better understand their institutional experience. As detailed in table 3 these included: current student enrolment and graduations, levels of dropouts, the number of teaching and administrative staff employed and the estimated cost of training. In total, 4560 medical students were currently enrolled at the 8 medical schools. We saw a year-on-year increase in student enrolment, which was largely reflected in small increases in student graduations where data were available; only Hawler and Sulaimani medical schools had small decreases in graduations between 2012 and 2014. Across the 8 medical schools, a total of 59 students had dropped out of their course in 2014, with a total 1105 teaching staff and 728 administrative staff employed in 2015. The estimated cost of training each medical student to graduation ranged from US$6450 to US$110 000.

Table 3.

Medical school student and human resource statistics

| Medical school | Al-Muthana | Diyala | Hawler | Jabir Ibn Hayyan | Kufa | Sulaimani | Tikrit | Wasit | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No medical students | 261 | 322 | 987 | 185 | 807 | 869 | 721 | 408 | 4560 | |

| Enrolment | ‘14–'15 | 67 | 60 | – | 100 | 160 | 147 | 118 | 77 | 729 |

| ‘13–'14 | 32 | 53 | 154 | 85 | 13 | 146 | 106 | 62 | 651 | |

| ‘12–'13 | 50 | 48 | 151 | – | 132 | 154 | 129 | – | 664 | |

| Δ in ‘14/15 since 08 | 17 | 10 | – | – | 85 | 45 | 67 | 17 | – | |

| Graduations | ‘13–'14 | 20 | 43 | 129 | 0 | 120 | 104 | 49 | 48 | 513 |

| ‘12–'13 | – | 32 | 138 | – | 105 | 122 | 45 | 35 | 477 | |

| Δ in ‘13–'14 since ‘08 | – | – | 11 | – | 22 | (15) | (3) | 48 | – | |

| Dropouts | ‘14 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 59 |

| No teaching staff | ‘15 | 39 | 53 | 263 | 40 | 221 | 203 | 216 | 70 | 1105 |

| Part- vs Full-time (%) | 50/50 | 75/25 | 1/99 | 0/100 | 0/100 | 0/100 | 28/72 | 10/90 | – | |

| ‘14 | 61 | 47 | 262 | 26 | 221 | – | 212 | 60 | 889 | |

| Δ in 14/15 since ‘08 | 21 | 20 | – | 40 | 24 | – | 15 | 43 | – | |

| Admin staff | ‘15 | 46 | 91 | 137 | – | 197 | 157 | 60 | 40 | 728 |

| ‘14 | 50 | 94 | 136 | 16 | 197 | 146 | 52 | 35 | 726 | |

| Δ in 14/15 since ‘08 | 36 | 51 | 17 | – | (23) | 157 | 19 | 20 | ||

| Average | ||||||||||

| Cost to train doctor ($) | 10 000 | 165 000 | – | 110 000 | 6450 | – | – | – | 72 862 | |

| Students/teaching staff ratio (2014/2015) | 6.69 | 6.08 | 3.75 | 4.63 | 3.65 | 4.28 | 3.34 | 5.83 | 4.78 | |

Participating medical school enrolment, graduations and dropouts; teaching and administrative (admin) staff; and cost to train each doctor (USD). ‘-‘ denotes missing data from respondent, brackets ‘()’ denote decreases.

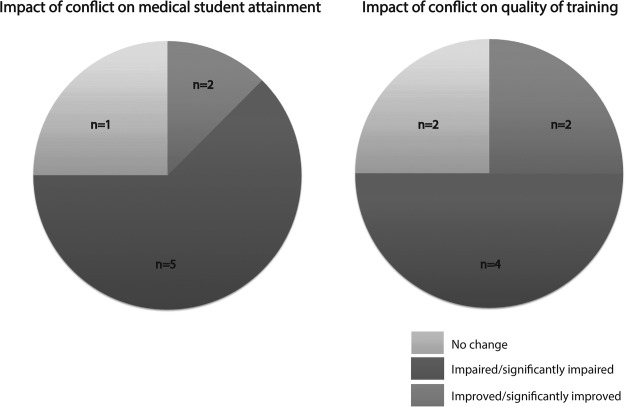

From this data, the staff-to-student ratio of each medical school was determined which averaged 4.78 students per teaching staff member (table 3); although schools have widely different student and staff numbers, their ratios appeared to be consistent (r2=0.9586) (see online supplementary appendix 4). Deans were asked what impact conflict was exerting on medical student attainment and training quality as shown in figure 2. Five of eight medical schools reported student academic attainment (success/performance) being impaired or significantly impaired, two felt there was no change and one felt it had improved. On quality of training: four of eight medical schools felt training had been impaired or significantly impaired, two felt there was no change and two felt it had improved. Subjective reasons cited by deans as to why training had been impaired included missed days of classes, and graduation of students with gaps in their knowledge. Deans also subjectively reported changes in student decision-making regarding enrolment, with the safety of the surrounding region increasingly influential in student decision-making on where to enrol.

Figure 2.

Deans’ perspectives on the impact of conflict on medical student attainment (academic achievement/success) (A) and quality of training (B). Numbers (n) refer to total respondents for each option.

Medical school deans reported facing challenges in staff recruitment and retention, and although numbers have increased since 2008, some staff are still unable or afraid to come to work. At the University of Al-Muthana, 50% are working part-time while at Diyala Medical School, as many as 75% of the staff are working part-time (table 3). Four (50%) medical schools reported experiencing financial challenges; deans commented that unreliable administrative resources including email and internet services were also hampering educational activities at medical schools.

Medical students

Respondents totalled 197 students from three medical schools spread across Iraq, as detailed in table 4 and figure 3. These students were from year 2 to 6 of their studies; 89% were ordinary students and 11% were guest students from other parts of Iraq. When asked on the impact of conflict on their quality of training: 63% of respondents from Baghdad, 57% from Basrah and 60% from Wasit University said their training had been impaired or significantly impaired by conflict (figure 4A). Common concerns of students across these medical schools included: their level of clinical competence, mental exhaustion and personal safety (figure 4B). Asked on the psychological impacts of conflict, students commonly cited anxiety and depression (figure 4B). Other impacts on their student experience included gaps in medical knowledge often due to missed teaching (figure 4B).

Table 4.

Medical student participant demographics

| Demographics | |

| Male | 77 |

| Female | 117 |

| Not given | 3 |

| Total | 197 |

| Medical school | |

| University of Baghdad | 100 |

| University of Basrah | 69 |

| University of Wasit | 28 |

| Stage of training | |

| Year 1 | 0 |

| Year 2 | 47 |

| Year 3 | 53 |

| Year 4 | 37 |

| Year 5 | 41 |

| Year 6 | 19 |

| Type of student | |

| Ordinary student | 175 |

| Guest (transferred) student | 22 |

Personal and academic demographics of medical student study participants.

Figure 3.

Geographical location of medical student participants’ medical school. Image generated using GoogleMaps. (1) University of Baghdad; (2)University of Basrah; (3) University of Wasit.

Figure 4.

Student perceptions on the impact of conflict on quality of medical training (A); main concerns, psychological and other impacts of conflict on the student experience (B). Where numbers (n) refer to total respondents for each option; % of students refers to the proportion of students selecting the option of total student participants across medical schools.

Medical students were asked whether they experienced personal attacks or threats to their safety as a result of conflict: 50% of respondents from Baghdad, 65% from Basrah and 75% from Wasit University reported they had (table 5); an overall average of 62% of students. Asked on student views of ‘dropping out’ (discontinuation of their studies) as a result of conflict, the majority of respondents had not considered it (table 5). Of the 22 guest students included in this survey: 11 (50%) expressed that their needs were being met by their host institution, 9 (40%) said they were not and 2 (10%) did not answer (table 5). Subjective responses from guest students included a desire for their hosts to introduce feedback mechanisms to inform understanding of guest student needs and current welfare, these included enhanced provision of psychological and social support.

Table 5.

Student safety, study plans and future career intentions

| Personal attacks/threats | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Per cent | No | Per cent | Do not know | Per cent | (n) | |

| Baghdad | 55 | 56 | 19 | 19 | 25 | 25 | 99 |

| Basrah | 45 | 65 | 13 | 19 | 11 | 16 | 69 |

| Wasit | 21 | 75 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 21 | 28 |

| Total | 121 | 61 | 33 | 17 | 42 | 21 | |

| Dropping out | |||||||

| Considering | Per cent | Not considering | Per cent | Do not know | Per cent | (n) | |

| Baghdad | 27 | 27 | 46 | 46 | 26 | 26 | 99 |

| Basrah | 20 | 29 | 34 | 49 | 15 | 22 | 69 |

| Wasit | 4 | 14 | 17 | 61 | 7 | 25 | 28 |

| Total | 51 | 26 | 97 | 49 | 48 | 25 | |

| Guest student needs | |||||||

| Being met | Per cent | Inadequate | Per cent | N/A | Per cent | ||

| 11 | 50 | 9 | 41 | 2 | 9 | 22 | |

| Future career intentions | |||||||

| Leave Iraq | Per cent | Stay in Iraq | Per cent | N/A | Per cent | ||

| 109 | 55 | 84 | 43 | 4 | 2 | 197 | |

Student safety, study plans and future career intentions. Numbers refer to total respondents for each option. (n)=total respondents for each medical school, % refers to the proportion selecting the option from each medical school, total % refers to the proportion selecting the option from total student participants across medical schools.

We then surveyed student career intentions after graduation. As detailed in table 5, the majority (109, 56%) of students’ intentions after graduation are to leave Iraq. Among these students, the majority wished to pursue a clinical career or undertake further study (data not shown). Of the 84 (42%) students who intended to stay in Iraq, the majority wished to pursue a clinical career or undertake further study (data not shown). Finally, we invited students to provide (without restriction) subjective comments on how the educational impacts of conflict could be mitigated. Ninety-two (47%) study participants replied with comments, these were grouped into personal, educational and other external themes which were then subdivided further as detailed in figure 5. These included improving student safety and support; changes to clinical training; greater international opportunities; and an end to conflict.

Figure 5.

Student perspectives on mitigating educational impact. Student subjective comments were thematically analysed, grouped and subgrouped. Numbers (n) refer to total respondents for each option. Themes were subgrouped according to personal, educational or other external factors.

Discussion

Health systems depend on local educational structures to facilitate training of an adequate supply of health professionals. Inadequate levels of physicians are associated with increased population disease burden and a reduction in health system performance.24–26 The impact of conflict on education is well described.4 26 Reports of the specific impact on medical education have arisen from several recent conflicts including Croatia,10 11 Liberia12 and Lebanon.18 These (predominantly retrospective) reports offer insight into the challenges experienced by medical students in times of conflict or insecurity, who can often find themselves subject to or even participating in the medical response to war.11 20 27 However, few studies have examined the perspectives of medical school deans and medical students during conflict.

This study was conducted in Iraq, a country that has experienced decades of conflict, violence and insecurity. During and after the 1990–1991 Gulf War, medical education in Iraq was impaired by a decade long intellectual embargo. This reduced access to educational medical books and academic exchange, and drove down academic and clinical standards, forcing many to leave Iraq.20 The 2003 invasion, war and subsequent violent insecurity has compounded this crisis, leading to an exodus of Iraqi academics and medical professionals.28 More recently, violence has intensified further still with the insurgence of non-state actor ‘Daesh’ (ISIL) leading to substantive internal displacement:22 the public health situation in Iraq is now critical.29 30

Medical schools

We identified 24 Iraqi medical schools from online searches, eight more than identified in a regional review from 2013.31 Participants in this study were spread across Iraq (figure 1), but none were in Anbar province in Western Iraq which has experienced some of the most intense violence.32 We found student enrolment and graduations at medical schools were relatively stable over the past 2 years, with the majority of medical schools reporting increases in student and staff appointments since 2008 (table 3). Interestingly, all participating medical schools had similar student to teaching staff ratios (see online supplementary appendix 4) suggesting that despite the conflict, medical education infrastructure and human resources remained balanced across the participating medical schools. The estimated cost of training each medical student ranged from US$6450 to US$110 000 compared to a global average of $113 000.24 The size of the variance in these figures—which only four medical schools were able to provide—warrants further attention. If true, it suggests a great variation in medical school expenditure which could be further assessed and optimised. The majority of deans felt medical student attainment and quality of training had been adversely affected by recent conflict (figure 2). Interestingly, Kufa Medical School reported an improvement in student attainment following the conflict, as since cessation of the international embargo significant efforts have been devoted to developing the institution including partnering with Leicester University's School of Medicine in the UK to advance its academic curriculum since 2012.

Medical students

A majority (61%) of students in this study felt that their quality of training had been impaired by the ongoing conflict (figure 4A). This seems plausible as evidence from the war in Croatia showed that medical students at Osijek University struggled to concentrate on their studies amidst the ongoing violence, eventually requiring their transfer to Zagreb Medical School.10 Student perceptions of violence are key influencers of educational achievement, with the stress and uncertainty associated with conflict disturbing all stages and actors in the educational process.33 Key concerns cited by medical students included their level of clinical competence (figure 4B); mirroring concerns raised by deans over the graduation of students with gaps in medical knowledge. Other concerns included: mental exhaustion; fear over their personal safety (figure 4B); anxiety and depression (figure 4B). Attacks on medical facilities, academics and clinicians in Iraq are a long-standing problem.34 The majority (61%) of medical students in this study felt they or their colleagues had been specifically targeted or threatened (table 5).

In light of these concerns, 26% of respondents wished to drop out and a further 25% were uncertain (table 5). This compares to a global average medical student attrition of 11.1% (range: 2.4–26.2%) derived from a meta-analysis of 40 international studies35—though the latter were confirmed ‘drop-outs’ rather than an intention to drop-out, as reported in this study. Conflict drives forced displacement, in the first half of 2015 this stood at 3.2 million people in Iraq.22 Medical students—who are often in great danger during conflict36—are frequently forced to transfer their studies for safety reasons.10 Among the 194 students that participated in this study, 22 (11%) were transferred or ‘guest’ students (table 5); 11 (50%) of whom felt their student needs (such as education and accommodation) were being met, in contrast 9 (41%) felt they were not and 2 (9%) did not answer (table 5).

Of most concern, the majority (56%) of students expressed a wish to leave Iraq after graduation (table 5). In comparison, a study of over 900 medical students from six African countries found 40% intended to continue their training abroad37; another study from Ghana of 393 medical students found 49% had intentions to continue postgraduate training abroad,38 while in Pakistan this rose to 60.4% in a study of 323 medical students.39 In all of these studies, the most common intended destinations for students was Western Europe and North America. Further, our finding accords with published cross-sectional studies of Iraqi doctor emigration intentions, where 50% of those responding to a national survey wanted to leave Iraq40; moreover, another study of 401 Iraqi doctors who had emigrated found less than a third intended to return to Iraq; the average age of this study population was 36 years, representing a cohort with decades of medical service left to offer.41 Indeed, physician job satisfaction and decisions to stay or leave Iraq are strongly linked to security and working conditions42; Iraq is for example, one of the largest contributors to the UK international medical graduate pool.43

These findings are particularly alarming given the already significant healthcare personnel shortages found in Iraq.44 Iraq's current physician density is 0.6 doctors/1000 population45; lower than the WHO target of 1/1000; WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) average of 1.6/100031 and global average of 1.2/1000.46 With a high birth rate47 that (population weighted) is the fourth largest in EMRO, and 33% higher than the regional average—physician graduations in Iraq need to expand significantly in order to both keep apace of population increases and achieve the WHO target; without which, an increase in disease burden is likely.26 That such a high proportion of current students are considering leaving Iraq after graduation warrants immediate attention.

Limitations

This study had a low number of medical school respondents, some of whom were uncontactable, while others may have experienced issues in storing and obtaining information thus precluding their participation. Owing to challenges in email reliability, students were invited to participate via online notices placed on social media outlets. Thus, we were unable to control respondent demographics or discern a response rate. Nevertheless, given the extremely challenging circumstances in Iraq and clear impact of medical education on health system capacity and performance,24 25 we feel this study offers important insights that inform educational and policy stakeholders minded to maintain and improve the current and future Iraqi health system.

Study implications and recommendations

This study is the first to document institutional and student insights of medical education amidst ongoing conflict. There is a need for more data on the impacts on medical education and other key institutions in civil society in states that are, like Iraq, experiencing violent conflict. Such information could inform strategies adopted by domestic governments, international organisations and other stakeholders to support the maintenance of civil society and domestic institutions in times of unrest. This could range from formal exchange or ‘buddy’ programmes with medical schools in the region or internationally; to social, physical and mental health support for medical students and faculty in-country.

We recommend:

Country-wide medical school needs assessment

This study has highlighted shortcomings in medical school resources and staff capacity that is impacting on medical education provision. Given the majority of Iraq's medical schools are unaccounted for in this study, we recommend a full national assessment be conducted, ideally by country stakeholders with WHO oversight, to systematically examine the needs of all medical schools and options for local, regional and international support.

Country-wide medical student cross-sectional survey

Medical student participants in this study indicated a high-degree of psychological stress; concern over clinical competence; the majority held intentions to leave Iraq. A survey of medical students coordinated by medical schools, national stakeholders such as IFMSA Iraq and Kurdistan—with oversight from WHO, could inform medical schools and educational stakeholders of the burden faced by Iraqi medical students. The survey would also help inform strategic decision-making necessary to improve student experience and retention after graduation.

Conclusion

The findings from this study provides insight into the medical school and student experience in Iraq amidst ongoing conflict. Medical schools are facing challenges in staff recruitment and adequate resource provision; the majority believe quality of training has suffered as a result. Medical students are experiencing added psychological stress and lower quality of teaching; the majority intend to leave Iraq after graduation. We recommend a country-wide nationally-coordinated needs assessment of medical schools, and cross-sectional survey of medical students, to identify areas for local, regional or international support necessary to maintain and improve Iraq's medical education and future health service.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank IFMSA Iraq, IFMSA Kurdistan, Dr Hilal Al-Saffar, Moa M Herrgård and Christopher Schürmann for their assistance.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Sondus Hassounah at @SondusHassounah

Contributors: All authors have participated fully in the conception, writing and critical review of this manuscript. All have seen and agreed to the submission of the final manuscript. AB-V was involved in the idea, literature search, data collection, writing, critical review. SH was involved in the literature search, writing, critical review. MS was involved in the literature search, data collection, writing, critical review. OAI was involved in the literature search, data collection, writing, critical review. CF was involved in the literature search, writing, critical review. TK was involved in the literature search, data collection, writing, critical review. SR was involved in the literature search, writing, critical review. AM was involved in the idea, writing, critical review.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: MS was a representative of IFMSA-Iraq (International federation of Medical Students’ Associations-Iraq) during the course of this study. OAI was a representative of IFMSA-Iraq (International federation of Medical Students’ Associations-Iraq) during the course of this study.

Ethics approval: Ethics Review Board of Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA (see online supplementary appendix 3).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Bank. Fragility, conflict and violence overview. 2015. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/overview.

- 2. Jackson A. The Cost of War Afghan Experiences of Conflict, 1978–2009. OXFAM, London; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiegel PB, Checchi F, Colombo S et al. Health-care needs of people affected by conflict: future trends and changing frameworks. Lancet 2010;375:341–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61873-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNESCO. The hidden crisis: Armed conflict and education. UNESCO, Paris; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krause K, Muggah R, Gilgen E. The Global Burden of Armed Violence. Geneva Declaration, Geneva; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leaning J, Guha-Sapir D. Natural disasters, armed conflict, and public health. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1836–42. 10.1056/NEJMra1109877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salama P, Spiegel P, Talley L et al. Lessons learned from complex emergencies over past decade. Lancet 2004;364:1801–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17405-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brundtland GH, Glinka E, Hausen HZ et al. Open letter: let us treat patients in Syria. Lancet 2013;382:1019–20. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61938-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arie S. Polio outbreak leads to calls for a “vaccination ceasefire” in Syria. BMJ 2013;347:f6682 10.1136/bmj.f6682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marusic M. War and medical education in Croatia. Acad Med 1994;69:111–13. 10.1097/00001888-199402000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marusic A, Marusic M. Clinical teaching in a time of war. Clin Teach 2004;1:19–22. 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2004.00014.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Challoner KR, Forget N. Effect of civil war on medical education in Liberia. Int J Emerg Med 2011;4:6. 10.1186/1865-1380-4-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.[No authors listed] Growth of aid and the decline of humanitarianism. Lancet 2010;375:253 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60110-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djalali A, Ingrassia PL, Corte FD et al. Identifying deficiencies in national and foreign medical team responses through expert opinion surveys: implications for education and training. Prehosp Disaster Med 2014;29:364–8. 10.1017/S1049023X14000600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu K, Stokes C, Trelles M et al. Improving effective surgical delivery in humanitarian disasters: lessons from Haiti. PLoS Med 2011;8(4):e1001025 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodon J, Maria Serrano JF, Giménez C. Managing cultural conflicts for effective humanitarian aid. Int J Prod Econ 2012;139:366–76. 10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.08.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diehl HS. The role of medical education in the war. Acad Med 1942;17:917–18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shehadi SI. Anatomy of a hospital in distress—the story of the American University of Beirut Hospital during the Lebanese civil war . Middle East J Anaesthesiol 1983;7:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batley NJ, Makhoul J, Latif SA. War as a positive medical educational experience. Med Educ 2008;42:1166–71. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03228.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richards LJ, Wall SN. Iraqi medical education under the intellectual embargo. Lancet 2000;355(9209):1093–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02049-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy BS, Sidel VW. Adverse health consequences of the Iraq War. Lancet 2013;381:949–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60254-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Relief Web. Iraq: Emergency response by humanitarian partners (March to July 2015). http://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/iraq-emergency-response-humanitarian-partners-march-july-2015 (accessed 17 Sep 2015).

- 23.Hasnawi SA. Physicians shortage in Iraq: impact and proposed solutions. Iraqi J Community Med 2013;26:214–18. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crisp N, Chen L. Global supply of health professionals. N Engl J Med 2014;370(10):950–7. 10.1056/NEJMra1111610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castillo-Laborde C. Human resources for health and burden of disease: an econometric approach. Hum Resour Health 2011;9:4 10.1186/1478-4491-9-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa GR. The civil war's medical cadets: medical students serving the Union. J Am Coll Surg 2001;193:81–9. 10.1016/S1072-7515(01)00864-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Guardian. The Iraqi brain drain. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/mar/24/iraq.jonathansteele (accessed 16 Sep 2006).

- 29.World Health Organization. Conflict and humanitarian crisis in Iraq. http://who.int/hac/crises/irq/iraq_phra_24october2014.pdf (accessed 17th September, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 30.UN agencies ‘broke and failing’ in face of ever-growing refugee crisis. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/06/refugee-crisis-un-agencies-broke-failing (accessed 17 Sep 2015).

- 31.Abdalla ME, Suliman RA. Overview of medical schools in the Eastern Mediterranean Region of the World Health Organization. East Mediterr Health J 2013;19:1020–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iraq launches new offensive to drive Isis from Anbar province. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/13/iraq-launches-new-offensive-to-drive-isis-from-anbar-province (accessed 17 Sep 2015).

- 33.Engel LC, Rutkowski D, Rutkowski L. The harsher side of globalisation: violent conflict and academic achievement. Global Soc Educ 2009;7:433–56. 10.1080/14767720903412242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webster P. Medical faculties decimated by violence in Iraq. CMAJ 2009;181:576–8. 10.1503/cmaj.109-3035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Neill LD, Wallstedt B, Eika B et al. Factors associated with dropout in medical education: a literature review. Med Educ 2011;45:440–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03898.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin A, Post N, Martin M. Syria: what should health care professionals do? J Glob Health 2014;4:010302 10.7189/jogh.04.010302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burch VC, McKinley D, van Wyk J et al. Career intentions of medical students trained in six sub-Saharan African countries. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2011;24:614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eliason S, Tuoyire DA, Awusi-Nti C et al. Migration intentions of Ghanaian medical students: the influence of existing funding mechanisms of medical education (“the fee factor)”. Ghana Med J 2014;48:78–84. 10.4314/gmj.v48i2.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheikh A, Naqvi SH, Sheikh K et al. Physician migration at its roots: a study on the factors contributing towards a career choice abroad among students at a medical school in Pakistan. Global Health 2012;8:43 10.1186/1744-8603-8-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Khalisi N. The Iraqi medical brain drain: a cross-sectional study. Int J Health Serv 2013;43:363–78. 10.2190/HS.43.2.j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malik S, Doocy S, Burnham G. Future plans of Iraqi physicians in Jordan: predictors of migration. Int Migr 2014;52:1–8. 10.1111/imig.12059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ali Jadoo SA, Aljunid SM, Dastan I et al. Job satisfaction and turnover intention among Iraqi doctors—a descriptive cross-sectional multicentre study. Hum Resour Health 2015;13:21 10.1186/s12960-015-0014-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.List of Registered Medical Practitioners—statistics. http://www.gmc-uk.org/doctors/register/search_stats.asp (accessed 31 Aug 2015).

- 44.Zarocostas J. Exodus of medical staff strains Iraq's health facilities. BMJ 2007;334(7599):865 10.1136/bmj.39195.466713.DB [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Bank. Data, Physicians (per 1,000 people). http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS (accessed 17 Sep 2015).

- 46.Boulet J, Bede C, McKinley D et al. An overview of the world's medical schools. Med Teach 2007;29:20–6. 10.1080/01421590601131823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Bank. Data—Crude Birth Rate per 1000 people. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.CBRT.IN (accessed 26 Nov 2015).